Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Borjigin

View on WikipediaThis article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: I haven't read most of the article, but it commences with two utterly obtuse sentences that signal to the reader that this page has absolutely zero intention of communicating information to the reader. (April 2025) |

| Borjigin ᠪᠣᠷᠵᠢᠭᠢᠨ Боржигин Budunzars Clan | |

|---|---|

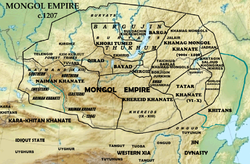

Mongol Empire c. 1207 | |

| Country | Mongol Empire, Northern Yuan dynasty, Mongolia, China (Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang) |

| Place of origin | Khamag Mongol |

| Founded | c. 900 AD (10th-Century) |

| Founder | Bodonchar Munkhag |

| Final ruler |

|

| Titles | Khagan, Khan, Ilkhan, Noyan, Tsar |

| Connected families | Khiyad Manghud Barlas Tayichuds Urud Chonos |

| Estate(s) | Mongolia Russia Central Asia Iran China |

| Deposition | 1930 |

| Cadet branches | All Genghisids lists: House of Ogedai House of Jochids (Girays, Shaybanids, Tore), House of Toluids Yuan Hulagu House of Chagatai |

The Borjigin or Borjigids[b] are a Mongol clan founded in the early 10th century by Bodonchar Munkhag.[c] The senior line of Borjigids provided ruling princes for Mongolia and Inner Mongolia until the 20th century.[5] The clan formed the ruling class among the Mongols and other peoples of Central Asia and Eastern Europe. Today, the Borjigids are found in Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang,[5] and genetic research shows that descent from Genghis Khan and Timur is common throughout Central and East Asia.[according to whom?]

Origin and name

[edit]According to The Secret History of the Mongols, the first Mongol was born from the union of a blue-grey wolf and a fallow doe. Their 11th-generation descendant Alan Gua was impregnated by a ray of light[6] and begat 5 sons, the youngest being Bodonchar Munkhag, progenitor of the Borjigids.[7][8] According to Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, many of the older Mongolian tribes were founded by members of the Borjigin clan, including Barlas, Urud, Manghud, Taichiut, Chonos, and Kiyat. Bodonchar's descendant Khabul Khan founded the Khamag Mongol confederation around 1131. His great-grandson Temujin ruled the Khamag Mongol and unified the other Mongol tribes under him, being declared Khagan in 1206 thus establishing the Mongol Empire.

The etymology of the word Borjigin is uncertain.

History

[edit]

Members of the Borjigin clan ruled over the Mongol Empire,[9] dominating large lands stretching from Java to Iran and from Indo-China to Novgorod. Many of the ruling dynasties that took power following the disintegration of the Mongol Empire were of Chinggisid, and thus Borjigid, ancestry. These included the Chupanids, the Jalayirids, the Barlas, the Manghud, the Onggirat, and the Oirats.

In 1368, the Borjigid Yuan dynasty of China was overthrown by the Ming dynasty. Members of this family continued to rule over northern China and the Mongolian Plateau into the 17th century, becoming known as the Northern Yuan dynasty. Descendants of Genghis Khan's brothers, Hasar and Belgutei, surrendered to the Ming in the 1380s. By 1470, the Borjigids power was severely weakened, and the Mongolian Plateau was almost in chaos.

Post-Mongol Empire

[edit]

After the breakup of the Golden Horde, the Khiyat tribe of Borjigids continued to rule in Crimea and Kazan until they were annexed by the Russian Empire in the late 18th century. In Mongolia, the Kublaids continued to reign as Khagan of the Mongols, with brief interruptions by the descendants of Ögedei and Ariq Böke.

Under Dayan Khan (1480–1517) a broad Borjigid revival reestablished Borjigid supremacy among the Mongols in Mongolia proper. His descendants proliferated and became a new ruling class. The Borjigin clan was the strongest of the 49 Mongol banners from which the Bontoi clan proper supported and fought for their Khan and for their honor. The eastern Khorchins were under the Hasarids, and the Ongnigud, Abagha Mongols were under the Belguteids and Temüge Odchigenids. A fragment of the Hasarids deported to Western Mongolia became the Khoshuts.

The Qing dynasty respected the Borjigin family and the early emperors married Hasarid Borjigids of the Khorchin. Even among the pro-Qing Mongols, traces of the alternative tradition survived. Aci Lomi, a banner general, wrote his History of the Borjigid Clan in 1732–35.[10] The 18th century and 19th century Qing nobility was adorned by the descendants of the early Mongol adherents including the Borjigin.[11]

Asian dynasties descended from Genghis Khan included the Yuan dynasty of China, the Ilkhanids of Persia, the Jochids of the Golden Horde, the Shaybanids of Siberia and Central Asia, and the Astrakhanids of Central Asia. Chinggisid descent played a crucial role in Tatar politics. For instance, Mamai had to exercise his authority through a succession of puppet khans but could not assume the title of khan himself because he lacked Genghisid lineage.

The word "Chinggisid" derives from the name of the Mongol conqueror Genghis (Chingis) Khan (c. 1162–1227 CE). Genghis and his successors created a vast empire stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Black Sea.

- The Chinggisid principle,[12] or golden lineage, was the rule of inheritance laid down in the (Yassa), the legal code attributed to Genghis Khan.

- A Chinggisid prince was one who could trace direct descent from Genghis Khan in the male line, and who could therefore claim high respect in the Mongol, Turkic and Asiatic world.

- The Chinggisid states were the successor states or Khanates after the Mongol empire broke up following the death of the Genghis Khan's sons and their successors.

- The term Chinggisid people was used[by whom?] to describe the people of Genghis Khan's armies who came in contact with Europeans. It applied primarily to the Golden Horde, led by Batu Khan, a grandson of Genghis. Members of the Horde were predominantly Kıpchak— Turkic-speaking people rather than Mongols. (Although the aristocracy was largely Mongol, Mongols were never more than a small minority in the armies and the lands they conquered.) Europeans often (incorrectly) called the people of the Golden Horde "Tartars".

Babur and Humayun, founders of the Mughal Empire in India, asserted their authority as Chinggisids, claiming descent through their maternal lineage.

The Chinggisid also include such dynasties and houses as Giray, Töre, House of Siberia, Ar begs, Yaushev family[13] and other.

The last ruling monarch of Chinggisid ancestry was Maqsud Shah, Khan of Kumul from 1908 to 1930.

Modern relevance

[edit]The Borjigin held power over Mongolia for many centuries (even during Qing period) and only lost power when Communists took control in the 20th century. Aristocratic descent was something to be forgotten in the socialist period.[14] Joseph Stalin's associates executed some 30,000 Mongols including Borjigin nobles in a series of campaigns against their culture and religion.[15] Clan association has lost its practical relevance in the 20th century, but is still considered a matter of honour and pride by many Mongolians. In 1920s the communist regime banned the use of clan names. When the ban was lifted again in 1997, and people were told they had to have surnames, most families had lost knowledge about their clan association. Because of that, a disproportionate number of families registered the most prestigious clan name Borjigin, many of them without historic justification.[16][17] The label Borjigin is used as a measure of cultural supremacy.[18]

In Inner Mongolia, the Borjigid or Kiyad name became the basis for many Chinese surnames adopted by ethnic Inner Mongols.[9] The Inner Mongolian Borjigin Taijis took the surname Bao (鲍, from Borjigid) and in Ordos Qi (奇, Qiyat). A genetic research has proposed that as many as 16 million men from populations as far apart as Hazaras in the West and Hezhe people to the east may have Borjigid-Kiyad ancestry.[19] The Qiyat clan name is still found among the Kazakhs, Uzbeks and Nogai Karakalpaks.

Yuan dynasty family tree

[edit]Genghis Khan founded the Mongol Empire in 1206. His grandson, Kublai Khan, after defeating his younger brother and rival claimant to the throne Ariq Böke, founded the Yuan dynasty of China in 1271. The dynasty was overthrown by the Ming dynasty during the reign of Toghon Temür in 1368, but it survived in the Mongolian Plateau, known as the Northern Yuan dynasty. Although the throne was usurped by Esen Taishi of the Oirats in 1453, he was overthrown in the next year. A recovery of the khaganate was achieved by Dayan Khan, but the territory was segmented by his descendants. The last khan Ligden died in 1634 and his son Ejei Khongor submitted himself to Hong Taiji the next year, ending the Northern Yuan regime.[20] However, the Borjigin nobles continued to rule their subjects until the 20th century under the Qing dynasty.[21][d]

Or in a different version (years of reign over the Northern Yuan dynasty [up to 1388] are given in brackets).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A Middle Mongolian plural-suffix -t has been written about by Éva Csáki in Middle Mongolian Loan Words in Volga Kipchak Languages.

- ^ /ˈbɔːrdʒɪɡɪn/; Mongolian: Боржигин, romanized: Borzhigin, ᠪᠣᠷᠵᠢᠭᠢᠨ pronounced [ˈpɔrt͡ɕɘkɘŋ]; simplified Chinese: 孛儿只斤; traditional Chinese: 孛兒只斤; pinyin: Bó'érjìjǐn; Russian: Борджигин, romanized: Bordžigin; English plural: Borjigins or Borjigid (from Middle Mongolian);[2][a] Manchu plural?:

[3]

[3]

- ^ The Secret History of the Mongols traces it back to Yesugei's ancestor Bodonchar[4]

- ^ Wada Sei did pioneer work on this field, and Honda Minobu and Okada Hidehiro modified it, using newly discovered Persian (Timurid) records and Mongol chronicles.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. William Benton. 1973. p. 726.

- ^ Histoire des campagnes de Gengis Khan, p. 119.

- ^ Li, p. 97.

- ^ Histoire des campagnes de Gengis Khan, p. 118.

- ^ a b Humphrey & Sneath, p. 27.

- ^ The Secret History of the Mongols, chapter 1, §§ 17, 21.

- ^ Franke, Twitchett & Fairbank, p. 330.

- ^ Kahn, p. 10.

- ^ a b Atwood, p. 45.

- ^ Perdue, p. 487.

- ^ Crossley, p. 213.

- ^ Halperin, chapter VIII.

- ^ Сабитов Ж. М. (2011). "Башкирские ханы Бачман и Тура" (in Russian) (Сибирский сборник. Выпуск 1. Казань ed.): 63–69.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Humphrey & Sneath, p. 28.

- ^ Weatherford, p. xv.

- ^ "In Search of Sacred Names".

- ^ Magnier.

- ^ Pegg, p. 22.

- ^ "The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols", pp. 717-721.

- ^ Heirman & Bumbacher, p. 395.

- ^ Sneath, p. 21.

Sources

[edit]- Atwood, C. P. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle. A Translucent Mirror.

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John King. The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368.

- "The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols". American Journal of Human Genetics, 72.

- Halperin, Charles J. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde: The Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20445-3. ISBN 978-0-253-20445-5.

- Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter. The Spread of Buddhism.

- Histoire des campagnes de Gengis Khan (in French). E. J. Brill.

- Humphrey, Caroline; Sneath, David. The End of Nomadism?.

- "In Search of Sacred Names", Mongolia Today, archived from the original on 2007-06-07.

- Kahn, Paul. The Secret History of the Mongols.

- Li, Gertraude Roth. Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents.

- Magnier, Mark (October 23, 2004). "Identity Issues in Mongolia". Los Angeles Times.

- Pegg, Carole. Mongolian Music, Dance & Oral Narrative.

- Perdue, Peter C. China Marches West.

- Sneath, David. Changing Inner Mongolia: Pastoral Mongolian Society and the Chinese State.

- Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Wada Sei 和田清. Tōashi Kenkyū (Mōko Hen) 東亜史研究 (蒙古編). Tokyo, 1959.

- Honda Minobu 本田實信. On the genealogy of the early Northern Yüan, Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, XXX-314, 1958.

- Okada Hidehiro 岡田英弘. Dayan Hagan no nendai ダヤン・ハガンの年代. Tōyō Gakuhō, Vol. 48, No. 3 pp. 1–26 and No. 4 pp. 40–61, 1965.

- Okada Hidehiro 岡田英弘. Dayan Hagan no sensei ダヤン・ハガンの先世. Shigaku Zasshi. Vol. 75, No. 5, pp. 1–38, 1966.