Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

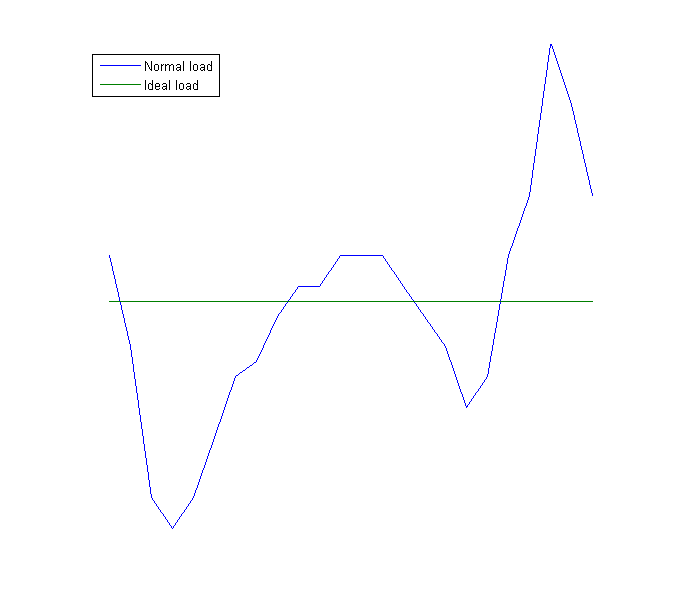

Load management

View on Wikipedia

Load management, also known as demand-side management (DSM), is the process of balancing the supply of electricity on the network with the electrical load by adjusting or controlling the load rather than the power station output. This can be achieved by direct intervention of the utility in real time, by the use of frequency sensitive relays triggering the circuit breakers (ripple control), by time clocks, or by using special tariffs to influence consumer behavior. Load management allows utilities to reduce demand for electricity during peak usage times (peak shaving), which can, in turn, reduce costs by eliminating the need for peaking power plants. In addition, some peaking power plants can take more than an hour to bring on-line which makes load management even more critical should a plant go off-line unexpectedly for example. Load management can also help reduce harmful emissions, since peaking plants or backup generators are often dirtier and less efficient than base load power plants. New load-management technologies are constantly under development — both by private industry[1] and public entities.[2][3]

Brief history

[edit]Modern utility load management began about 1938, using ripple control. By 1948 ripple control was a practical system in wide use.[4]

The Czechs first used ripple control in the 1950s. Early transmitters were low power, compared to modern systems, only 50 kilovolt-amps. They were rotating generators that fed a 1050 Hz signal into transformers attached to power distribution networks. Early receivers were electromechanical relays. Later, in the 1970s, transmitters with high-power semiconductors were used. These are more reliable because they have no moving parts. Modern Czech systems send a digital "telegram". Each telegram takes about thirty seconds to send. It has pulses about one second long. There are several formats, used in different districts.[5]

In 1972, Theodore George "Ted" Paraskevakos, while working for Boeing in Huntsville, Alabama, developed a sensor monitoring system which used digital transmission for security, fire, and medical alarm systems as well as meter-reading capabilities for all utilities. This technology was a spin-off of his patented automatic telephone line identification system, now known as caller ID. In, 1974, Paraskevakos was awarded a U.S. patent for this technology.[6]

At the request of the Alabama Power Company, Paraskevakos developed a load-management system along with automatic meter-reading technology. In doing so, he utilized the ability of the system to monitor the speed of the watt power meter disc and, consequently, power consumption. This information, along with the time of day, gave the power company the ability to instruct individual meters to manage water heater and air conditioning consumption in order to prevent peaks in usage during the high consumption portions of the day. For this approach, Paraskevakos was awarded multiple patents.[7]

Advantages and operating principles

[edit]Since electrical energy is a form of energy that cannot be effectively stored in bulk, it must be generated, distributed, and consumed immediately. When the load on a system approaches the maximum generating capacity, network operators must either find additional supplies of energy or find ways to curtail the load, hence load management. If they are unsuccessful, the system will become unstable and blackouts can occur.

Long-term load management planning may begin by building sophisticated models to describe the physical properties of the distribution network (i.e. topology, capacity, and other characteristics of the lines), as well as the load behavior. The analysis may include scenarios that account for weather forecasts, the predicted impact of proposed load-shed commands, estimated time-to-repair for off-line equipment, and other factors.

The utilization of load management can help a power plant achieve a higher capacity factor, a measure of average capacity utilization. Capacity factor is a measure of the output of a power plant compared to the maximum output it could produce. Capacity factor is often defined as the ratio of average load to capacity or the ratio of average load to peak load in a period of time. A higher load factor is advantageous because a power plant may be less efficient at low load factors, a high load factor means fixed costs are spread over more kWh of output (resulting in a lower price per unit of electricity), and a higher load factor means greater total output. If the power load factor is affected by non-availability of fuel, maintenance shut-down, unplanned breakdown, or reduced demand (as consumption pattern fluctuate throughout the day), the generation has to be adjusted, since grid energy storage is often prohibitively expensive.

Smaller utilities that buy power instead of generating their own find that they can also benefit by installing a load control system. The penalties they must pay to the energy provider for peak usage can be significantly reduced. Many report that a load control system can pay for itself in a single season.

Comparisons to demand response

[edit]When the decision is made to curtail load, it is done so on the basis of system reliability. The utility in a sense "owns the switch" and sheds loads only when the stability or reliability of the electrical distribution system is threatened. The utility (being in the business of generating, transporting, and delivering electricity) will not disrupt their business process without due cause. Load management, when done properly, is non-invasive, and imposes no hardship on the consumer. The load should be shifted to off peak hours.

Demand response places the "on-off switch" in the hands of the consumer using devices such as a smart grid controlled load control switch. While many residential consumers pay a flat rate for electricity year-round, the utility's costs actually vary constantly, depending on demand, the distribution network, and composition of the company's electricity generation portfolio. In a free market, the wholesale price of energy varies widely throughout the day. Demand response programs such as those enabled by smart grids attempt to incentivize the consumer to limit usage based upon cost concerns. As costs rise during the day (as the system reaches peak capacity and more expensive peaking power plants are used), a free market economy should allow the price to rise. A corresponding drop in demand for the commodity should meet a fall in price. While this works for predictable shortages, many crises develop within seconds due to unforeseen equipment failures. They must be resolved in the same time-frame in order to avoid a power blackout. Many utilities who are interested in demand response have also expressed an interest in load control capability so that they might be able to operate the "on-off switch" before price updates could be published to the consumers.[8]

The application of load control technology continues to grow today with the sale of both radio frequency and powerline communication based systems. Certain types of smart meter systems can also serve as load control systems. Charge control systems can prevent the recharging of electric vehicles during peak hours. Vehicle-to-grid systems can return electricity from an electric vehicle's batteries to the utility, or they can throttle the recharging of the vehicle batteries to a slower rate.[9]

Ripple control

[edit]Ripple control is a common form of load control, and is used in many countries around the world, including the United States, Australia, Czech Republic, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, and South Africa. Ripple control involves superimposing a higher-frequency signal (usually between 100 and 1600 Hz[10]) onto the standard 50–60 Hz of the main power signal. When receiver devices attached to non-essential residential or industrial loads receive this signal, they shut down the load until the signal is disabled or another frequency signal is received.

Early implementations of ripple control occurred during World War II in various parts of the world using a system that communicates over the electrical distribution system. Early systems used rotating generators attached to distribution networks through transformers. Ripple control systems are generally paired with a two- (or more) tiered pricing system, whereby electricity is more expensive during peak times (evenings) and cheaper during low-usage times (early morning).

Affected residential devices will vary by region, but may include residential electric hot-water heaters, air conditioners, pool pumps, or crop-irrigation pumps. In a distribution network outfitted with load control, these devices are outfitted with communicating controllers that can run a program that limits the duty cycle of the equipment under control. Consumers are usually rewarded for participating in the load control program by paying a reduced rate for energy. Proper load management by the utility allows them to practice load shedding to avoid rolling blackouts and reduce costs.

Ripple Control is also used to turn off photovoltaic systems in case of electricity overproduction.

Ripple control can be unpopular because sometimes devices can fail to receive the signal to turn on comfort equipment, e.g. hot water heaters or baseboard electrical heaters. Modern electronic receivers are more reliable than old electromechanical systems. Also, some modern systems repeat the telegrams to turn on comfort devices. Also, by popular demand, many ripple control receivers have a switch to force comfort devices on.

Modern ripple controls send a digital telegram, from 30 to 180 seconds long. Originally these were received by electromechanical relays. Now they are often received by microprocessors. Many systems repeat telegrams to assure that comfort devices (e.g. water heaters) are turned on. Since the broadcast frequencies are in the range of human hearing, they often vibrate wires, filament light-bulbs or transformers in an audible way.[5]

The telegrams follow different standards in different areas. For example, in the Czech Republic, different districts use "ZPA II 32S", "ZPA II 64S" and Versacom. ZPA II 32S sends a 2.33 second on, a 2.99 second off, then 32 one-second pulses (either on or off), with an "off time" between each pulse of one second. ZPA II 64S has a much shorter off time, permitting 64 pulses to be sent, or skipped.[5]

Nearby regions use different frequencies or telegrams, to assure that telegrams operate only in the desired region. The transformers that attach local grids to interties intentionally do not have the equipment (bridging capacitors) to pass ripple control signals into long-distance power lines.[5]

Each data pulse of a telegram could double the number of commands, so that 32 pulses permit 2^32 distinct commands. However, in practice, particular pulses are linked to particular types of device or service. Some telegrams have unusual purposes. For example most ripple control systems have a telegram to set clocks in attached devices, e.g. to midnight.[5]

Zellweger off-peak is one common brand of ripple control systems.

Radio ripple control

[edit]In recent years, radio-based load management (sometimes known as "radio ripple control") signalling systems have been introduced to replace traditional power wire ripple signalling systems.[11] Some radio-based load management systems have been criticised for lacking sufficient security measures, potentially compromising power grid security or allowing street lighting to be turned on or off.[12]

Frequency-based decentralized demand control

[edit]Greater loads physically slow the rotors of a grid's synchronized generators. This causes AC mains to have a slightly reduced frequency when a grid is heavily loaded. The reduced frequency is immediately sensible across the entire grid. Inexpensive local electronics can easily and precisely measure mains frequencies and turn off sheddable loads. In some cases, this feature is nearly free, e.g. if the controlling equipment (such as an electric power meter, or the thermostat in an air-conditioning system) already has a microcontroller. Most electronic electric power meters internally measure frequency, and require only demand control relays to turn off equipment. In other equipment, often the only needed extra equipment is a resistor divider to sense the mains cycle and a schmitt trigger (a small integrated circuit) so the microcontrollers' digital input can sense a reliable fast digital edge. A schmitt trigger is already standard equipment on many microcontrollers.

The main advantage over ripple control is greater customer convenience: Unreceived ripple control telegrams can cause a water heater to remain off, causing a cold shower. Or, they can cause an airconditioner to remain off, resulting in a sweltering home. In contrast, as the grid recovers, its frequency naturally rises to normal, so frequency-controlled load control automatically enables water heaters, air-conditioners and other comfort equipment. The cost of equipment can be less, and there are no concerns about overlapping or unreached ripple control regions, mis-received codes, transmitter power, etc.

The main disadvantage compared to ripple control is a less fine-grained control. For example, a grid authority has only a limited ability to select which loads are shed. In controlled war-time economies, this can be a substantial disadvantage.

The system was invented in PNNL in the early 21st century, and has been shown to stabilize grids.[13]

Examples of schemes

[edit]In many countries, including United States, United Kingdom and France, the power grids routinely use privately held, emergency diesel generators in load management schemes[14]

Florida

[edit]The largest residential load control system in the world[15] is found in Florida and is managed by Florida Power and Light. It utilizes 800,000 load control transponders (LCTs) and controls 1,000 MW of electrical power (2,000 MW in an emergency). FPL has been able to avoid the construction of numerous new power plants due to their load management programs.[16]

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]

Since the 1950s, Australia and New Zealand have had a system of load management based on ripple control, allowing the electricity supply for domestic and commercial water storage heaters to be switched off and on, as well as allowing remote control of nightstore heaters and street lights. Ripple injection equipment located within each local distribution network signals to ripple control receivers at the customer's premises. Control may either done manually by the local distribution network company in response to local outages or requests to reduce demand from the transmission system operator (i.e. Transpower), or automatically when injection equipment detects mains frequency falling below 49.2 Hz. Ripple control receivers are assigned to one of several ripple channels to allow the network company to only turn off supply on part of the network, and to allow staged restoration of supply to reduce the impact of a surge in demand when power is restored to water heaters after a period of time off.

Depending on the area, the consumer may have two electricity meters, one for normal supply ("Anytime") and one for the load-managed supply ("Controlled"), with Controlled supply billed at a lower rate per kilowatt-hour than Anytime supply. For those with load-managed supply but only a single meter, electricity is billed at the "Composite" rate, priced between Anytime and Controlled.

Czech Republic

[edit]The Czechs have operated ripple control systems since the 1950s.[5]

France

[edit]France has an EJP tariff, which allows it to disconnect certain loads and to encourage consumers to disconnect certain loads.[17] This tariff is no longer available for new clients (as of July 2009).[18] The Tempo tariff also includes different types of days with different prices, but has been discontinued for new clients as well (as of July 2009).[19] Reduced prices during nighttime are available for customers for a higher monthly fee.[20]

Germany

[edit]The distribution system operator Westnetz and gridX piloted a load management solution. The solution enables the grid operator to communicate with local energy management systems and adjust the available load for EV charging in response to the state of the grid.[21]

United Kingdom

[edit]Rltec in the UK in 2009 reported that domestic refrigerators are being sold fitted with their dynamic load response systems. In 2011 it was announced that the Sainsbury supermarket chain will use dynamic demand technology on their heating and ventilation equipment.[22]

In the UK, night storage heaters are often used with a time-switched off-peak supply option - Economy 7 or Economy 10. There is also a programme that allows industrial loads to be disconnected using circuit breakers triggered automatically by frequency sensitive relays fitted on site. This operates in conjunction with Standing Reserve, a programme using diesel generators.[23] These can also be remotely switched using BBC Radio 4 Longwave Radio teleswitch.

SP transmission deployed Dynamic Load Management scheme in Dumfries and Galloway area using real time monitoring of embedded generation and disconnecting them, should an overload be detected on the transmission Network.

See also

[edit]- Energy management system

- Energy storage as a service (ESaaS)

- National Grid (Great Britain): Estimating costs per kWh of transmission

- Calculating the cost of back up: See spark spread

- Energy in the United Kingdom

- National Grid Reserve Service

- Cost of electricity by source

- Diesel-electric transmission

- Motor–generator

- Three-phase electric power

- Load bank

- Wet stacking

References

[edit]- ^ Example of largest load management system developed by private industry

- ^ US Dept. Of Energy, Office of Electricity Delivery and Electricity Reliability

- ^ Analysis of current US DOE Projects Archived October 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ross, T. W.; Smith, R. M. A. (October 1948). "Centralized ripple control on high-voltage networks". Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers - Part II: Power Engineering. 95 (47): 470–480. doi:10.1049/ji-2.1948.0126. Retrieved 18 October 2019.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "Ripple control". EnergoConsult CB S.R.O. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ U.S. Patent No. 3,842,208 (sensor monitoring device)

- ^ U.S. patents Nos. 4,241,237, 4,455,453 and 7,940,901 (remote management of products and services) as well as Canadian Patent No. 1,155,243 (apparatus and method for remote sensor monitoring, metering and control)

- ^ N. A. Sinitsyn. S. Kundu, S. Backhaus (2013). "Safe Protocols for Generating Power Pulses with Heterogeneous Populations of Thermostatically Controlled Loads". Energy Conversion and Management. 67: 297–308. arXiv:1211.0248. Bibcode:2013ECM....67..297S. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2012.11.021. S2CID 32067734.

- ^ Liasi, Sahand Ghaseminejad; Golkar, Masoud Aliakbar (2017). "Electric vehicles connection to microgrid effects on peak demand with and without demand response". 2017 Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE). pp. 1272–1277. doi:10.1109/IranianCEE.2017.7985237. ISBN 978-1-5090-5963-8. S2CID 22071272.

- ^ Jean Marie Polard. "The Remote Control Frequencies". Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ A. Dán; D. Divényi; B. Hartmann; P. Kiss; D. Raisz; I. Vokony (2024-01-17). "Perspectives of Demand-Side Management in a Smart Metered Environment". RE&PQJ. 9 (1). doi:10.24084/repqj09.564. ISSN 2172-038X.

- ^ Bräunlein, Fabian; Melette, Luca (2024). "[38c3] BlinkenCity: Radio-Controlling Street Lamps and Power Plants". 38th Chaos Communication Congress. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ Kalsi, K.; et al. "Loads as a Resource: Frequency Responsive Demand Control" (PDF). pnnl.gov. U.S. Government. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Claverton Energy experts library Archived February 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Andreolas (February 2004). "Mega Load Management System Pays Dividends". Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "FPL Files Proposal to Enhance Energy Conservation Programs". May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Claverton Energy Experts

- ^ (in French) EDF EPJ Archived June 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in French) EDF Tempo Archived June 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in French) EDF Price grid

- ^ "GridX Press Release: Following successful pilot, gridX agrees on cooperation with Westnetz".

- ^ News/media/downloads | Dynamic Demand, Smart Grid solutions, energy balancing

- ^ Commercial Opportunities for Back-Up Generation and Load Reduction via National Grid, the National Electricity Transmission System Operator (NETSO) for England, Scotland, Wales and Offshore.