Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Meteor shower

View on Wikipedia

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere at extremely high speeds on parallel trajectories. Most meteors are smaller than a grain of sand, so almost all of them disintegrate and never hit the Earth's surface. Very intense or unusual meteor showers are known as meteor outbursts and meteor storms, which produce at least 1,000 meteors an hour, most notably from the Leonids.[1] The Meteor Data Centre lists over 900 suspected meteor showers of which about 100 are well established.[2] Several organizations point to viewing opportunities on the Internet.[3] NASA maintains a daily map of active meteor showers.[4]

Historically, meteor showers were regarded as an atmospheric phenomenon. In 1794, Ernst Chladni proposed that meteors originated in outer space. The Great Meteor Storm of 1833 led Denison Olmsted to show it arrived as a cloud of space dust, with the streaks forming a radiant point in the direction of the constellation of Leo. In 1866, Giovanni Schiaparelli proposed that meteors came from comets when he showed that the Leonid meteor shower shared the same orbit as the Comet Tempel. Astronomers learned to compute the orbits of these clouds of cometary dust, including how they are perturbed by planetary gravity. Fred Whipple in 1951 proposed that comets are "dirty snowballs" that shed meteoritic debris as their volatiles are ablated by solar energy in the inner Solar System.

Historical developments

[edit]Historical records suggest that Spartan observations of meteor showers occurred as early as 1200 BCE. There are detailed records from ancient archives showing they were observed from China, Japan, and Korea.[5][6] There are multiple chronicles where Medieval Arabs recorded meteor showers, as they regarded them as good omens.[7] A meteor shower in August 1583 was recorded in the Timbuktu manuscripts.[8][9][10] The Lyrids meteor shower is the oldest such event to be continuously recorded, with records in China dating back to 687 BCE.[11]

In 1789, Antoine Lavoisier published the first modern chemistry textbook titled, Traité Élémentaire de Chimie. In it, he speculated that dust rising into the upper atmosphere could be consolidated into lumps of matter by lightning, forming fiery meteors as they plummeted to the ground. At the start of the 19th century, this became one of the most favored hypothesis for the formation on meteors. However, in 1794, German scientist Ernst Chladni proposed that meteorites originated in outer space, and as evidence he published a book linking fireballs to iron meteorites. This proposal was initially met with disbelief from some scientists, initially including Alexander von Humboldt, as it contradicted Isaac Newton's statement that space must be empty for planets to continue along their orbits.[12][5]

In the modern era, the first great meteor storm was the Leonids of November 1833. One estimate is a peak rate of over one hundred thousand meteors an hour,[13] but another, done as the storm abated, estimated more than two hundred thousand meteors during the 9 hours of the storm,[14] over the entire region of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. American Denison Olmsted (1791–1859) explained the event most accurately. After spending the last weeks of 1833 collecting information, he presented his findings in January 1834 to the American Journal of Science and Arts, published in January–April 1834,[15] and January 1836.[16] He noted the shower was of short duration and was not seen in Europe, and that the meteors radiated from a point in the constellation of Leo. He speculated the meteors had originated from a cloud of particles in space.[17] Work continued, yet coming to understand the annual nature of showers though the occurrences of storms perplexed researchers.[18]

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli ascertained the relation between meteors and comets in a series of letters to Angelo Secchi late in 1866. He was able to demonstrate that the Leonid meteor shower shared the same orbit as the Comet Tempel.[19][5] Biela's Comet, discovered in 1772 and identified as periodic in 1826, was observed to have two components in 1846. During the 1852 return, both components were fainter and had a greater separation. In 1868, Edmund Weiss determined that the Earth would intersect the orbit of this comet in 1872, and a strong meteor shower was observed at that time. This meteor stream, now referred to as the Andromedids, further established the connection between comets and meteor showers.[20]

In the 1890s, Irish astronomer George Johnstone Stoney (1826–1911) and British astronomer Arthur Matthew Weld Downing (1850–1917) were the first to attempt to calculate the position of the dust at Earth's orbit, taking into account the gravitational perturbations of Jupiter. They studied the dust ejected in 1866 by comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle before the anticipated Leonid shower return of 1898 and 1899. Meteor storms were expected, but the final calculations showed that most of the dust would be far inside Earth's orbit. The same results were independently arrived at by Adolf Berberich of the Königliches Astronomisches Rechen Institut (Royal Astronomical Computation Institute) in Berlin, Germany.[21] Although the absence of meteor storms that season confirmed the calculations, the advance of much better computing tools was needed to arrive at reliable predictions.

In 1981, Donald K. Yeomans of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory reviewed the history of meteor showers for the Leonids and the history of the dynamic orbit of Comet Tempel-Tuttle.[22] A graph[23] from it was adapted and re-published in Sky and Telescope.[24] It showed relative positions of the Earth and Tempel-Tuttle and marks where Earth encountered dense dust. This showed that the meteoroids are mostly behind and outside the path of the comet, but paths of the Earth through the cloud of particles resulting in powerful storms were very near paths of nearly no activity.

In 1985, E. D. Kondrat'eva and E. A. Reznikov of Kazan State University first correctly identified the years when dust was released which was responsible for several past Leonid meteor storms. In 1995, Peter Jenniskens predicted the 1995 Alpha Monocerotids outburst from dust trails.[25] In anticipation of the 1999 Leonid storm, Robert H. McNaught,[26] David Asher,[27] and Finland's Esko Lyytinen were the first to apply this method in the West.[28][29] In 2006 Jenniskens published predictions for future dust trail encounters covering the next 50 years.[30] Jérémie Vaubaillon continues to update predictions based on observations each year for the Institut de Mécanique Céleste et de Calcul des Éphémérides (IMCCE).[31]

Radiant point

[edit]

Because meteor shower particles are all traveling in parallel paths and at the same velocity, they will appear to an observer below to radiate away from a single point in the sky. This radiant point is caused by the effect of perspective, similar to parallel railroad tracks converging at a single vanishing point on the horizon. Meteor showers are normally named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to originate. This "fixed point" slowly moves across the sky during the night due to the Earth turning on its axis, the same reason the stars appear to slowly march across the sky.[32] The radiant also moves slightly from night to night against the background stars (radiant drift) due to the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.[33] See IMO Meteor Shower Calendar 2017 (International Meteor Organization) for maps of drifting "fixed points".

The geocentric velocity of the meteors can vary considerably between showers. For example, the velocity is around 27 km/s for the Taurids and 71 km/s for the Leonids. (Compare to the Earth's average orbital velocity of 29.8 km/s.[34]) Incoming meteors produce a measureable light curve along their trajectory, which varies in brightness by the rate of ablation.[35] The observed heights for meteor ionization is from 70 to 110 km, where the atmosphere is sufficiently dense to heat the projectiles.[36] A typical meteor in a shower has a diameter of 5 μm with a density of 2 g cm−3. It starts to melt at a temperature of around 1800 K.[37]

As the Earth rotates, the shower rate will be low when the radiant point is near the horizon, then it will rise to at least 50% of maximum when the radiant point reaches an altitude of 30° above the horizon. Optimum viewing is when the radiant point is at an angle of 45°, or half way up the sky, as the meteors are still passing through a thicker column of air. The longer, more prominent trails will then be observed 30–60° away from the radiant point.[38] Most meteor showers improve their visibility after midnight, as the observer's position becomes more oriented toward the direction of the Earth's orbit around the Sun. For this reason, the best viewing time for a meteor shower is generally slightly before dawn — a compromise between the maximum number of meteors available for viewing and the brightening sky, which makes them harder to see.[39]

Naming

[edit]Meteor showers are named after the nearest constellation, or bright star with a Greek or Roman letter assigned that is close to the radiant position at the peak of the shower, whereby the grammatical declension of the Latin possessive form is replaced by "id" or "ids."[40] Hence, meteors radiating from near the star Delta Aquarii (declension "-i") are called the Delta Aquariids. The International Astronomical Union's Working Group on Meteor Shower Nomenclature and the IAU's Meteor Data Center keep track of meteor shower nomenclature and which showers are established.[41][42]

Origin of meteoroid streams

[edit]

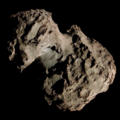

A meteor shower results from an interaction between a planet, such as Earth, and streams of debris from a comet (or occasionally an asteroid). Comets can produce debris by water vapor drag, as demonstrated by Fred Whipple in 1951,[43] and by breakup. Whipple envisioned comets as "dirty snowballs", made up of rock embedded in ice, orbiting the Sun. The "ice" may be water, methane, ammonia, or other volatiles, alone or in combination. The "rock" may vary in size from a dust mote to a small boulder. Dust mote sized solids are orders of magnitude more common than those the size of sand grains, which, in turn, are similarly more common than those the size of pebbles, and so on. When the ice warms and sublimates, the vapor can drag along dust, sand, and pebbles.

Each time a comet swings by the Sun in its orbit, some of its ice vaporizes, and a certain number of meteoroids will be shed.[44] The meteoroids spread out along the entire trajectory of the comet to form a meteoroid stream, also known as a "dust trail"[45] (as opposed to a comet's "gas tail" caused by the tiny particles that are quickly blown away by solar radiation pressure).

Recently, Peter Jenniskens has argued that most of our short-period meteor showers are not from the normal water vapor drag of active comets, but the product of infrequent disintegrations, when large chunks break off a mostly dormant comet. Examples are the Quadrantids and Geminids, which originated from a breakup of asteroid-looking objects, (196256) 2003 EH1 and 3200 Phaethon, respectively, about 500 and 1000 years ago. The fragments tend to fall apart quickly into dust, sand, and pebbles and spread out along the comet's orbit to form a dense meteoroid stream, which subsequently evolves into Earth's path.[30]

Dynamical evolution of meteoroid streams

[edit]Shortly after Whipple predicted that dust particles traveled at low speeds relative to the comet, Milos Plavec was the first to offer the idea of a dust trail, when he calculated how meteoroids, once freed from the comet, would drift mostly in front of or behind the comet after completing one orbit. The effect is simple celestial mechanics – the material drifts only a little laterally away from the comet while drifting ahead or behind the comet because some particles make a wider orbit than others.[30] These dust trails are sometimes observed in comet images taken at mid infrared wavelengths (heat radiation), where dust particles from the previous return to the Sun are spread along the orbit of the comet.[46]

The gravitational pull of the planets determines where the dust trail would pass by Earth orbit, much like a gardener directing a hose to water a distant plant. Most years, those trails would miss the Earth altogether, but in some years, the Earth is showered by meteors. This effect was first demonstrated from observations of the 1995 alpha Monocerotids,[47][48] and from earlier not widely known identifications of past Earth storms.

Over more extended periods, the dust trails can evolve in complicated ways. For example, the orbits of some repeating comets, and meteoroids leaving them, are in resonant orbits with Jupiter or one of the other large planets – so many revolutions of one will equal another number of the other. This creates a shower component called a filament.[49]

A second effect is a close encounter with a planet. When the meteoroids pass by Earth, some are accelerated (making wider orbits around the Sun), others are decelerated (making shorter orbits), resulting in gaps in the dust trail in the next return (like opening a curtain, with grains piling up at the beginning and end of the gap). Also, Jupiter's perturbation can dramatically change sections of the dust trail, especially for a short period comets, when the grains approach the giant planet at their furthest point along the orbit around the Sun, moving most slowly. As a result, the trail has a clumping, a braiding or a tangling of crescents, of each release of material.[citation needed]

The third effect is that of radiation pressure which will push less massive particles into orbits further from the Sun – while more massive objects (responsible for bolides or fireballs) will tend to be affected less by radiation pressure. This makes some dust trail encounters rich in bright meteors, others rich in faint meteors.[citation needed] Over time, these effects disperse the meteoroids and create a broader stream. The meteors we see from these streams are part of annual showers, because Earth encounters those streams every year at much the same rate.

When the meteoroids collide with other meteoroids in the zodiacal cloud, they lose their stream association and become part of the "sporadic meteors" background.[citation needed] Long since dispersed from any stream or trail, they form isolated meteors, not a part of any shower. These random meteors will not appear to come from the radiant of the leading shower.

Famous meteor showers

[edit]

The peak rate of a meteor shower is measured by the zenith hourly rate (ZHR), which is the expected number of meteors visible to the naked eye when the radiant point is at the zenith; that is, at the highest point in the night sky. For younger streams that are more clumpy, the rate can vary year to year with peak meteor "storms" occurring with the orbital period of the stream. Some storms have measured hundreds and even thousands of meteors per hour. The showers typically showing the highest ZHR are the Perseids (75/hr), Geminids (75/hr), and Quadrantids (60/hr).[50]

Perseids and Leonids

[edit]In most years, the most reliable meteor shower is the Perseids, which peak on 12 August of each year at over one meteor per minute.[51] NASA has an estimator tool to calculate how many meteors per hour are visible from one's observing location.

The Leonid meteor shower peaks around 17 November of each year. In multiples of 33 years, the Leonid shower produces a meteor storm peaking at rates of thousands of meteors per hour.[50] Leonid storms gave birth to the term meteor shower when it was first realised that, during the November 1833 storm, the meteors radiated from near the star Gamma Leonis.[citation needed] The last Leonid storms were in 1999, 2001 (two), and 2002 (two). Before that, there were storms in 1767, 1799, 1833, 1866, 1867, and 1966.[52] When the Leonid shower is not storming, it is less active than the Perseids.[50]

Other meteor showers

[edit]Established meteor showers

[edit]Official names are given in the International Astronomical Union's list of meteor showers.[53]

| Shower | Time | Parent object |

|---|---|---|

| Quadrantids | early January | The same as the parent object of minor planet 2003 EH1,[54] and Comet C/1490 Y1.[55][56] Comet C/1385 U1 has also been studied as a possible source.[57] |

| Lyrids | late April | Comet Thatcher[58] |

| Pi Puppids (periodic) | late April | Comet 26P/Grigg–Skjellerup[59] |

| Eta Aquariids | early May | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Arietids | mid-June | Comet 96P/Machholz, Marsden and Kracht comet groups complex[1][60] |

| Beta Taurids | late June | Comet 2P/Encke |

| June Bootids (periodic) | late June | Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke |

| Southern Delta Aquariids | late July | Comet 96P/Machholz, Marsden and Kracht comet groups complex[1][60] |

| Alpha Capricornids | late July | Comet 169P/NEAT[61] |

| Perseids | mid-August | Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle |

| Kappa Cygnids | mid-August | Minor planet 2008 ED69[62] |

| Aurigids (periodic) | early September | Comet C/1911 N1 (Kiess)[63] |

| Draconids (periodic) | early October | Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner |

| Orionids | late October | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Southern Taurids | early November | Comet 2P/Encke |

| Northern Taurids | mid-November | Minor planet 2004 TG10 and others[1][64] |

| Andromedids (periodic) | mid-November | Comet 3D/Biela[65] |

| Alpha Monocerotids (periodic) | mid-November | unknown[66] |

| Leonids | mid-November | Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle |

| Phoenicids (periodic) | early December | Comet 289P/Blanpain[67] |

| Geminids | mid-December | Minor planet 3200 Phaethon[68] |

| Ursids | late December | Comet 8P/Tuttle[69] |

| Canis-Minorids |

Extraterrestrial meteor showers

[edit]

Any other Solar System body with a reasonably transparent atmosphere can also have meteor showers. As the Moon is in the neighborhood of Earth it can experience the same showers, but will have its own phenomena due to its lack of an atmosphere per se, such as vastly increasing its sodium tail.[70] NASA now maintains an ongoing database of observed impacts on the moon[71] maintained by the Marshall Space Flight Center whether from a shower or not.

Many planets and moons have impact craters dating back large spans of time. But new craters, perhaps even related to meteor showers are possible. Mars, and thus its moons, is known to have meteor showers.[72] These have not been observed on other planets as yet but may be presumed to exist. For Mars in particular, although these are different from the ones seen on Earth because of the different orbits of Mars and Earth relative to the orbits of comets. The Martian atmosphere has less than one percent of the density of Earth's at ground level; at their upper edges, where meteoroids strike, the two are more similar. Because of the similar air pressure at altitudes for meteors, the effects are much the same. Only the relatively slower motion of the meteoroids due to increased distance from the sun should marginally decrease meteor brightness. This is somewhat balanced because the slower descent means that Martian meteors have more time to ablate.[73]

On March 7, 2004, the panoramic camera on Mars Exploration Rover Spirit recorded a streak which is now believed to have been caused by a meteor from a Martian meteor shower associated with comet 114P/Wiseman-Skiff. A strong display from this shower was expected on December 20, 2007. Other showers speculated about are a "Lambda Geminid" shower associated with the Eta Aquariids of Earth (i.e., both associated with Comet 1P/Halley), a "Beta Canis Major" shower associated with Comet 13P/Olbers, and "Draconids" from 5335 Damocles.[74]

Isolated massive impacts have been observed at Jupiter: The 1994 Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 which formed a brief trail as well, and successive events since then (see List of Jupiter events.) Meteors or meteor showers have been discussed for most of the objects in the Solar System with an atmosphere: Mercury,[75] Venus,[76] Saturn's moon Titan,[77] Neptune's moon Triton,[78] and Pluto.[79]

See also

[edit]- American Meteor Society (AMS)

- Earth-grazing fireball

- International Meteor Organization (IMO)

- List of meteor showers

- Meteor procession

- North American Meteor Network (NAMN)

- Radiant – point in the sky from which meteors appear to originate

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Jenniskens, P. (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.

- ^ Meteor Data Center list of Meteor Showers

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas, "The Quadrantids and Other Meteor Showers That Will Light Up Night Skies in 2018", The New York Times, January 2, 2018

- ^ NASA Meteor Shower Portal

- ^ a b c Williams, Iwan P.; Murad, Edmond (2002). "Introduction". In Murad, Edmond; Williams, Iwan P. (eds.). Meteors in the Earth's Atmosphere: Meteoroids and Cosmic Dust and Their Interactions with the Earth's Upper Atmosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80431-8.

- ^ Yang, Hong-Jin; et al. (May 2005). "Analysis of historical meteor and meteor shower records: Korea, China, and Japan". Icarus. 175 (1): 215–225. arXiv:astro-ph/0501216. Bibcode:2005Icar..175..215Y. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.10.007.

- ^ Rada, W. S.; Stephenson, F. R. (March 1992). "A Catalogue of Meteor Showers in Mediaeval Arab Chronicles". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 33 (1): 5. Bibcode:1992QJRAS..33....5R.

- ^ Holbrook, Jarita C.; Medupe, R. Thebe; Johnson Urama (2008). African Cultural Astronomy. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-6638-2.

- ^ Abraham, Curtis (15 August 2007). "Stars of the Sahara". New Scientist. 195 (2617): 39–41. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(07)62093-4. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-07-21.

- ^ Hammer, Joshua (2016). The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu And Their Race to Save the World's Most Precious Manuscripts. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-4767-7743-6.

- ^ Usó, M. J. Martínez; et al. (November 15, 2023). "The Lyrids meteor shower: A historical perspective". Planetary and Space Science. 238 105803. Bibcode:2023P&SS..23805803M. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2023.105803. hdl:10234/205174. 105803.

- ^ Marvin, U. B. (2006). "Meteorites in history: an overview from the Renaisscence to the 20th Century". In McCall, G. J. H.; Bowden, A. J.; Howarth, R. J. (eds.). The History of Meteoritics and Key Meteorite Collections: Fireballs, Falls and Finds. Special publication. Vol. 256. Geological Society of London. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-86239-194-9.

- ^ Rao, Joe (November 12, 2010). "The 1833 Leonid Meteor Shower: A Frightening Flurry". Space.com. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ "Brief history of the Leonid shower". Leonic MAC. NASA. Retrieved 2025-08-15.

- ^ Olmsted, Denison (1833). "Observations on the Meteors of November 13th, 1833". The American Journal of Science and Arts. 25: 363–411. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Olmsted, Denison (1836). "Facts respecting the Meteoric Phenomena of November 13th, 1834". The American Journal of Science and Arts. 29 (1): 168–170.

- ^ "Observing the Leonids". Meteor Showers Online. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-03-04. Retrieved 2013-03-04. Gary W. Kronk

- ^ F. W. Russell, Meteor Watch Organizer, by Richard Taibi, May 19, 2013, accessed 21 May 2013

- ^ Sheehan, William (2022). Planets and Perception: Telescopic Views and Interpretations, 1609-1909. University of Arizona Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8165-4680-0.

- ^ Williams, I. P. (1992). Ferraz-Mello, Sylvio (ed.). The Dynamics of Meteoroid Streams (lecture). Chaos, Resonance, and Collective Dynamical Phenomena in the Solar System: Proceedings of the 152nd Symposium of the International Astronomical Union held in Angra dos Reis, Brazil, 15-19 July, 1991. International Astronomical Union. Symposium. Vol. 152. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 299. Bibcode:1992IAUS..152..299W.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-316-34782-9.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. (September 1981). "Comet Tempel-Tuttle and the Leonid meteors". Icarus. 47 (3): 492–499. Bibcode:1981Icar...47..492Y. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(81)90198-6.

- ^ "Plot of meteoroids and Comet Tempel-Tuttle". January 7, 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-11-23.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. (June 30, 2007). "Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle and the Leonid Meteors" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-06-30.(1996, see p. 6)

- ^ Article published in 1997, notes prediction in 1995 - Jenniskens, P.; et al. (1997). "The Detection of a Dust Trail in the Orbit of an Earth-threatening Long-Period Comet". Astrophysical Journal. 479 (1): 441. Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..441J. doi:10.1086/303853.

- ^ McNaught, Rob (March 7, 2007). "Re: (meteorobs) Leonid Storm?". Archived from the original on 2007-03-07. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ "Blast from the Past". Armagh Observatory press release. April 21, 1999. Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ^ Mitton, Jacqueline (August 30, 1999). "Fine Leonid Meteor Displays Predicted Through To 2002". Royal Astronomical Society Press Notice. Ref. PN 99/27. Archived from the original on 2000-01-15. Retrieved 2003-03-09.

- ^ Riley, Chris (November 17, 1999). "Voyage through a comet's trail, The 1998 Leonids sparkled over Canada". Retrieved 2025-08-15.

- ^ a b c Jenniskens, P. (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 355–472. ISBN 978-1-316-34782-9.

- ^ "IMCCE Prediction page". October 8, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- ^ Lewis, T.; Hollis, H. P., eds. (1901). "Stationary Meteor Radiants". The Observatory. 24 (309): 359.

- ^ McIntosh, R. A. (June 1932). "Meteors". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 26: 193. Bibcode:1932JRASC..26..193M.

- ^ Williams, David R. (November 15, 2024). "Earth Fact Sheet". NSSDCA. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2024-12-30.

- ^ Koten, P.; et al. (December 2004). "Atmospheric trajectories and light curves of shower meteors". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 428 (2): 683–690. Bibcode:2004A&A...428..683K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041485.

- ^ Lukianova, Renata; et al. (August 2018). "Recognition of Meteor Showers From the Heights of Ionization Trails". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 123 (8): 7067–7076. Bibcode:2018JGRA..123.7067L. doi:10.1029/2018JA025706.

- ^ Vondrak, T.; et al. (December 2008). "A chemical model of meteoric ablation". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 8 (23): 7015–7031. Bibcode:2008ACP.....8.7015V. doi:10.5194/acp-8-7015-2008.

- ^ Lunsford, Robert (2009). Meteors and How to Observe Them. Astronomers' Observing Guides. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 145–147. ISBN 978-0-387-09461-8.

- ^ Lisle, Jason (2012). The Stargazer's Guide to the Night Sky. New Leaf Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-89051-641-6.

- ^ Jopek, Tadeusz J.; et al. (June 2023). "New nomenclature rules for meteor showers adopted". New Astronomy Reviews. 96 101671. id. 101671. arXiv:2211.01350. Bibcode:2023NewAR..9601671J. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2022.101671.

- ^ Jopek, T. J.; et al. (July 2011). Cooke, W. J.; et al. (eds.). The Working Group on Meteor Showers Nomenclature: A History, Current Status and a Call for Contributions (PDF). Meteoroids: The Smallest Solar System Bodies, Proceedings of the Meteoroids Conference held in Breckenridge, Colorado, USA, May 24-28, 2010. pp. 7–13. Bibcode:2011msss.conf....7J. NASA/CP-2011-216469. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ Jopek, Tadeusz Jan; Kaňuchová, Zuzana (September 2017). "IAU Meteor Data Center-the shower database: A status report". Planetary and Space Science. 143: 3–6. arXiv:1607.00661. Bibcode:2017P&SS..143....3J. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2016.11.003.

- ^ Whipple, F. L. (1951). "A Comet Model. II. Physical Relations for Comets and Meteors". Astrophysical Journal. 113: 464. Bibcode:1951ApJ...113..464W. doi:10.1086/145416.

- ^ Wesołowski, M.; et al. (March 2020). "Selected mechanisms of matter ejection out of the cometary nuclei". Icarus. 338 113546. id. 113546. Bibcode:2020Icar..33813546W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113546.

- ^ Fulle, M. (2004). "Motion of cometary dust" (PDF). In Festou, M. C.; et al. (eds.). Comets II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 565–575. Bibcode:2004come.book..565F. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ Sykes, Mark V.; Walker, Russell G. (February 1992). "Cometary dust trails I. Survey". Icarus. 95 (2): 180–210. Bibcode:1992Icar...95..180S. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90037-8.

- ^ Jenniskens, P. (1997). "Meteor stream activity IV. Meteor outbursts and the reflex motion of the Sun". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 317: 953–961. Bibcode:1997A&A...317..953J.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; et al. (1997). "The detection of a dust trail in the orbit of an Earth-threatening long-period comet". Astrophysical Journal. 479 (1): 441–447. Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..441J. doi:10.1086/303853.

- ^ Soja, R. H.; et al. (June 2011). "Dynamical resonant structures in meteoroid stream orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (2): 1059–1076. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.1059S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18442.x.

- ^ a b c Nicolson, Iain (1999). Unfolding Our Universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59270-3.

- ^ Reynolds, Mike D. (2010). Falling Stars: A Guide to Meteors & Meteorites (2 ed.). Stackpole Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8117-4221-4.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (2001). "Ready for the storm". Radiant, Journal of the Dutch Meteor Society. 23 (5): 91. Bibcode:2001Rad....23...91J.

- ^ "List of all meteor showers". International Astronomical Union. 15 August 2015.

- ^ Jenniskens, P. (March 2004). "2003 EH1 is the Quadrantid shower parent comet". Astronomical Journal. 127 (5): 3018–3022. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.3018J. doi:10.1086/383213.

- ^ Ball, Phillip (2003). "Dead comet spawned New Year meteors". Nature. doi:10.1038/news031229-5.

- ^ Haines, Lester, Meteor shower traced to 1490 comet break-up: Quadrantid mystery solved, The Register, January 8, 2008.

- ^ Micheli, Marco; et al. (May 16, 2008). "Updated analysis of the dynamical relation between asteroid 2003 EH1 and comets C/1490 Y1 and C/1385 U1". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 390 (1): L6 – L8. arXiv:0805.2452. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.390L...6M. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00510.x. S2CID 119299384.

- ^ Martínez Usó, M. J.; et al. (November 2023). "The Lyrids meteor shower: A historical perspective". Planetary and Space Science. 238 105803. Bibcode:2023P&SS..23805803M. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2023.105803. hdl:10234/205174.

- ^ Vaubaillon, J. (2004). Triglav-Čekada, M.; Trayner, C. (eds.). What happened with pi-Puppids in April 2003?. Proceedings of the International Meteor Conference, Bollmannsruh, Germany, September 19-21, 2003. International Meteor Organization. pp. 140–143. Bibcode:2004pimo.conf..140V.

- ^ a b Sekanina, Zdeněk; Chodas, Paul W. (December 2005). "Origin of the Marsden and Kracht Groups of Sunskirting Comets. I. Association with Comet 96P/Machholz and Its Interplanetary Complex". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 161 (2): 551. Bibcode:2005ApJS..161..551S. doi:10.1086/497374.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Vaubaillon, J. (2010). "Minor Planet 2002 EX12 (=169P/NEAT) and the Alpha Capricornid Shower". Astronomical Journal. 139 (5): 1822–1830. Bibcode:2010AJ....139.1822J. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/5/1822. S2CID 59523258.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Vaubaillon, J. (2008). "Minor Planet 2008 ED69 and the Kappa Cygnid Meteor Shower" (PDF). Astronomical Journal. 136 (2): 725–730. Bibcode:2008AJ....136..725J. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/2/725. S2CID 122768057.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter; Vaubaillon, Jérémie (2007). "An Unusual Meteor Shower on 1 September 2007". Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 88 (32): 317–318. Bibcode:2007EOSTr..88..317J. doi:10.1029/2007EO320001.

- ^ Porubčan, V.; Kornoš, L.; Williams, I.P. (2006). "The Taurid complex meteor showers and asteroids". Contributions of the Astronomical Observatory Skalnaté Pleso. 36 (2): 103–117. arXiv:0905.1639. Bibcode:2006CoSka..36..103P.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Vaubaillon, J. (2007). "3D/Biela and the Andromedids: Fragmenting versus Sublimating Comets" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 134 (3): 1037. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.1037J. doi:10.1086/519074. S2CID 18785028.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; et al. (1997). "The Detection of a Dust Trail in the Orbit of an Earth-threatening Long-Period Comet". Astrophysical Journal. 479 (1): 441. Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..441J. doi:10.1086/303853.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Lyytinen, E. (2005). "Meteor Showers from the Debris of Broken Comets: D/1819 W1 (Blanpain), 2003 WY25, and the Phoenicids". Astronomical Journal. 130 (3): 1286–1290. Bibcode:2005AJ....130.1286J. doi:10.1086/432469.

- ^ Brian G. Marsden (1983-10-25). "IAUC 3881: 1983 TB AND THE GEMINID METEORS; 1983 SA; KR Aur". International Astronomical Union Circular. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; et al. (2002). "Dust Trails of 8P/Tuttle and the Unusual Outbursts of the Ursid Shower". Icarus. 159 (1): 197–209. Bibcode:2002Icar..159..197J. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6855.

- ^ Hunten, D. M. (1991). "A possible meteor shower on the Moon". Geophysical Research Letters. 18 (11): 2101–2104. Bibcode:1991GeoRL..18.2101H. doi:10.1029/91GL02543.

- ^ Mohon, Lee (13 February 2017). "Lunar Impacts". NASA. Archived from the original on 2023-03-15.

- ^ "Meteor showers at Mars". Archived from the original on 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ "Can Meteors Exist at Mars?". Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "Meteor Showers and their Parent Bodies". Archived from the original on 2008-10-03. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ Rosemary M. Killen; Joseph M. Hahn (December 10, 2014). "Impact Vaporization as a Possible Source of Mercury's Calcium Exosphere". Icarus. 250: 230–237. Bibcode:2015Icar..250..230K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.035. hdl:2060/20150010116.

- ^ Christou, Apostolos A. (2007). "The P/Halley Stream: Meteor Showers on Earth, Venus and Mars". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 102 (1–4): 125–131. doi:10.1007/s11038-007-9201-3. S2CID 54709255.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily. "Meteor showers on Titan: an example of why Twitter is awesome for scientists and the public". Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- Note also the Huygens lander was studied for its meteoric entry and an observation campaign was attempted: An Artificial meteor on Titan?, by Ralph D. Lorenz, journal??, vol 43, issue 5, October 2002, pp. 14–17 and Lorenz, Ralph D. (2006). "Huygens entry emission: Observation campaign, results, and lessons learned". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (E7) 2005JE002603. Bibcode:2006JGRE..111.7S11L. doi:10.1029/2005JE002603.

- ^ Pesnell, W. Dean; et al. (March 27, 2014). "Watching meteors on Triton" (PDF). Icarus (169): 482–491. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ^ Kosarev, I. B.; Nemtchinov, I. V. (2002). "IR Flashes induced by meteoroid impacts onto Pluto's surface" (PDF). Microsymposium. 36. MS 050.

External links

[edit]- Meteor Showers, by Sky and Telescope

- Six Not-So-Famous Summer Meteor Showers Joe Rao (SPACE.com)

- The American Meteor Society

- The International Meteor Organisation

- Meteor Shower Portal shows the direction of active showers each night on a celestial sphere.

Meteor shower

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

A meteor shower is a celestial event characterized by the transient appearance of numerous meteors radiating from a common point in the sky, known as the radiant, resulting from Earth's passage through a stream of small meteoroids.[5] These meteoroids, typically ranging from dust grains to pea-sized particles, originate as debris shed by comets or occasionally asteroids within the solar system.[5] When these meteoroids intersect Earth's atmosphere at high velocities, they experience intense frictional heating due to collisions with air molecules, leading to ablation—a process where the meteoroid's surface material vaporizes and erodes rapidly.[11] This ablation compresses and ionizes the surrounding air, forming a plasma that emits visible light as a streak or trail, commonly perceived as a shooting star; the meteoroid itself rarely survives to reach the ground.[11] The light is primarily produced by the glowing ionized gases rather than the meteoroid material alone.[12] Key characteristics of meteor showers include entry speeds ranging from 11 to 72 km/s, durations spanning hours to several days with activity peaking over a shorter interval, and observed rates varying from a few meteors per hour under typical conditions to over 1,000 per hour during intense events known as meteor storms.[14][15] Meteor showers are predictable and occur at consistent times each year as Earth crosses established debris streams.[16]Distinction from Related Phenomena

Meteor showers are periodic increases in the number of visible meteors caused by Earth passing through a concentrated stream of debris from a comet or asteroid, resulting in multiple meteors appearing to radiate from a common point over a short duration, typically hours to days. In contrast, sporadic meteors occur randomly throughout the year as isolated events from diffuse meteoroid populations, without such clustering or shared orbital origins.[17][18] Fireballs, also known as bolides, refer to exceptionally bright individual meteors that can reach an apparent magnitude brighter than -4, often producing audible booms or explosions upon fragmentation, and may originate from either sporadic sources or meteor showers. Unlike the distributed, moderate-intensity display of a meteor shower, which involves numerous fainter meteors from a common stream, a fireball is a singular, high-energy event that stands out due to its size and luminosity, potentially leading to meteorite falls if fragments survive atmospheric entry.[19][20] Auroras, or northern and southern lights, arise from charged particles in the solar wind interacting with Earth's magnetosphere and upper atmosphere, exciting gases to emit diffuse, shimmering lights at altitudes around 100 km, whereas meteor showers result from the physical ablation of solid meteoroids entering the atmosphere at high velocities, producing streak-like trails from friction. Similarly, artificial satellite reentries involve human-made objects disintegrating slowly over tens of seconds to minutes at lower speeds (around 8 km/s), creating prolonged, tumbling fireballs or debris trains, in opposition to the rapid, sub-second flashes of natural meteor shower particles traveling at 10-70 km/s.[21] Meteors in showers represent the atmospheric phase where meteoroids vaporize completely, generating light but leaving no solid remnants, while meteorites are the rare surviving fragments of larger meteoroids that withstand ablation and reach Earth's surface. Common misconceptions further blur these lines; for instance, "shooting stars" in folklore often symbolize wishes or omens but are simply individual meteors, not actual stars falling, and persistent aircraft contrails—condensation trails from jet exhaust—can mimic linear meteor paths but persist for minutes or hours as clouds, lacking the brief, colorful streak of true meteors.[1][22][23]Observation and Detection

Radiant Point

The radiant point of a meteor shower is the apparent location on the celestial sphere from which the meteors appear to originate during the event. This point is an optical illusion resulting from the geometry of observation, where individual meteors' trails seem to diverge outward from a common direction in the sky.[24] The position of the radiant is typically specified by its right ascension and declination coordinates and serves as a key identifier for associating meteors with a specific shower.[25] Physically, the radiant arises because meteoroids within a stream travel on nearly parallel trajectories toward Earth, with their velocities aligned due to their shared orbital origin around the Sun. From the observer's perspective on Earth's surface, these parallel paths create a convergence effect similar to parallel railroad tracks appearing to meet at a distant point on the horizon. Although the meteoroids' speeds vary slightly—typically by a few kilometers per second—this dispersion causes the radiant to have a finite angular size, often spanning several degrees, rather than being a single pinpoint. Backward extensions of the observed meteor trails intersect at the radiant, while forward extensions converge at the anti-radiant, a point approximately 180 degrees opposite on the sky, confirming the parallelism of the incoming paths.[26][27] To determine the radiant, astronomers rely on coordinated visual or instrumental observations from multiple sites, often separated by tens to hundreds of kilometers, allowing triangulation of individual meteor trajectories to compute the incoming velocity vector's direction. Software tools, such as the Radiant program developed by the International Meteor Organization, process these data to map radiant distributions and densities, while star charts aid in real-time identification during observations. Historically, the radiant concept was recognized by 19th-century astronomers, with Giovanni Schiaparelli advancing its understanding in 1867 by demonstrating through orbital calculations that radiant positions align with cometary paths, establishing the link between showers and their parent bodies.[28][29][24] Over a shower's duration, the radiant may appear fixed for short-lived events, maintaining a stable position relative to the stars, or exhibit gradual motion—typically about 1 degree per day eastward—for longer-active streams, reflecting Earth's orbital progression through the meteoroid trail. This movement underscores the dynamic geometry between Earth's path and the stream's filamentary structure.[30]Visibility, Intensity, and Measurement

The visibility of a meteor shower depends on several key factors that can enhance or diminish the observer's ability to detect meteors. Interference from the Moon's phase is particularly significant, as a waxing or full Moon scatters light across the sky, making faint meteors harder to see and potentially reducing observed rates by up to 50% or more during unfavorable lunar conditions. Light pollution from artificial sources in urban and suburban areas further degrades visibility by creating a glow that overwhelms dimmer meteor trails, often limiting sightings to brighter events in affected regions.[32] Latitude and longitude play crucial roles in determining the radiant point's elevation above the horizon for a given observer, with higher elevations providing a wider effective viewing field and thus better opportunities for sightings, while low elevations near the horizon restrict visibility due to atmospheric extinction and limited sky coverage.[33] Meteor shower intensity is standardized through metrics that account for observational biases and ideal conditions. The Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) serves as the primary measure, defined as the hypothetical number of meteors a single observer with a limiting magnitude of +6.5 would see per hour if the radiant were directly overhead (at the zenith) in a clear, moonless sky free of light pollution or obstructions.[34] This correction normalizes raw counts to compare shower strengths across different locations and times, with typical ZHR values ranging from 5-10 for minor showers to over 100 for major ones like the Perseids.[35] Complementing ZHR, the population index (r) quantifies the cumulative distribution of meteor magnitudes, which is the ratio of the number of meteors at magnitude m+1 (fainter) to those at m (brighter), where values around 2.5 indicate a shower dominated by fainter meteors, lower r values suggest a higher proportion of brighter meteors, and higher r values indicate an even greater dominance of fainter ones.[36] Measurements of meteor shower activity employ a range of techniques tailored to visibility constraints. Visual counting remains a foundational method, where trained observers follow International Meteor Organization (IMO) protocols to tally meteors brighter than their individual limiting magnitude over a defined field of view, with data corrected for radiant elevation and sky transparency to compute ZHR. For daytime showers invisible to the eye, radar systems detect meteors by monitoring ionized trails in the upper atmosphere, enabling quantification of activity levels that can reach 60-200 meteors per hour for strong events like the Arietids.[37][38] Modern camera networks, such as the IMO Video Meteor Network and the Global Meteor Network, use arrays of wide-field video systems with automated detection software to capture trajectories, magnitudes, and orbits with sub-degree accuracy, supporting real-time flux monitoring and population index calculations across global sites.[39][40] Predicting the timing of a meteor shower's peak relies on numerical orbital models that simulate the geometry of Earth-stream encounters. These models integrate the parent comet's orbit with perturbations to forecast the solar longitude at maximum activity, typically achieving predictions within hours for established showers.[41] However, actual peaks can vary by days due to the inhomogeneous, filamentary structure of meteoroid streams, which causes fluctuations in encounter density from year to year.[42] Optimal observation practices emphasize minimizing interference while prioritizing comfort and safety. Selecting dark sky sites, such as those certified by the International Dark-Sky Association, is essential to escape light pollution, with travel to rural areas often required for ZHRs approaching theoretical maxima.[43] Sessions should align with predicted peak windows, preferably in the hours before dawn when the radiant rises higher and the sky is darkest, allowing 20-30 minutes for eyes to adapt fully.[44] Practical tips include lying supine or using a reclining chair to scan broad sky areas without neck strain, dressing in layers for cold nights, and avoiding bright devices to preserve night vision; no telescopes are needed, as wide-field naked-eye viewing captures the full shower display.[45]Nomenclature and Classification

Naming Conventions

Meteor showers are systematically named according to guidelines established by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which prioritize deriving the name from the constellation containing the radiant point, the apparent origin of the meteors in the sky. This convention ensures a standardized, astronomical basis for identification, reflecting the shower's observed direction. Exceptions are permitted for showers linked to specific comet parent bodies or long-standing historical designations, though the IAU emphasizes constellation-derived names to maintain consistency across catalogs.[46][47] To facilitate cataloging, each recognized shower receives a unique three-letter code derived from the Latin abbreviation of its associated constellation, such as PER for a shower radiating from Perseus. Provisional or newly proposed showers are assigned a provisional designation based on the date of submission to the IAU Meteor Data Center, in the format MYYYY-LN (e.g., M2022-K3), where YYYY is the year, L a letter for the half-month of submission, and N a sequential number, allowing temporary tracking before full establishment. These codes are maintained in the IAU Meteor Data Center database to avoid duplication and support international collaboration.[47] The process for officially recognizing and naming a meteor shower follows a two-step protocol overseen by the IAU Working Group on Meteor Shower Nomenclature. Initially, a shower is added to the Working List if observations demonstrate consistent activity over multiple returns, a well-defined radiant position, and preliminary orbital elements distinguishing it from known streams; this requires submissions from multiple observers or organizations like the International Meteor Organization (IMO). Upon further verification—including multi-year data confirming orbital similarity and exclusion of sporadic meteors—the shower advances to the List of Established Showers, granting permanent naming rights. This rigorous criteria prevent premature assignments and ensure scientific validity.[47][48] Historically, meteor shower naming evolved from informal, mythological, or calendar-based descriptions in ancient records to a scientific framework in the 19th century, when astronomers began associating showers with constellations based on radiant positions. The IAU formalized these practices in 2006 through its initial nomenclature rules, which were simplified and updated in 2022 to adopt a more streamlined two-stage process akin to asteroid designations, reducing complexity from prior multi-branch systems.[49][47] Special cases address challenges like daytime showers, which are named using the same constellation convention but often detected via radio forward-scatter or radar signatures rather than visual observation due to sunlight interference. Showers with variable or diffuse radiants are assigned names based on the primary or mean radiant location, ensuring alignment with the core guidelines while accommodating observational nuances.[50][51]Active Periods and Streams

Meteor showers exhibit active periods defined by the temporal window during which Earth intersects a meteoroid stream, encompassing the start, peak, and end dates of observable activity. These periods arise as Earth traverses the stream's debris trail along its heliocentric orbit, with the start marking the initial encounter with the stream's leading edge, the peak occurring when Earth passes through the densest concentration of meteoroids, and the end signifying the exit from the trailing edge. Typically lasting 1 to 2 weeks, the duration reflects the stream's width and the relative velocity between Earth and the meteoroids, allowing for a gradual increase and decrease in meteor flux around the maximum.[25][52] Meteoroid streams are classified as compact or diffuse based on their spatial density and structural coherence. Compact streams consist of tightly bound concentrations of particles following nearly identical orbits, resulting in short-duration showers with high peak intensities and well-defined radiants. In contrast, diffuse streams feature broader dispersions of meteoroids, often due to gravitational perturbations or ejection dynamics, leading to extended active periods and lower, more sustained flux levels. Many streams exhibit filamentary structures—narrow, elongated sub-components within the broader stream—that can produce multiple activity peaks as Earth encounters successive filaments during a single annual passage.[53] The annual predictability of meteor showers stems from the fixed geometry of Earth's orbit relative to the stream's heliocentric path, enabling consistent intersections at specific solar longitudes each year. This orbital alignment ensures recurring activity, with the timing determined by the stream's nodal points where its orbit crosses the ecliptic plane near Earth's path. Forecasts rely on these dynamical parameters to anticipate peak times and intensities, supporting reliable predictions for observers and spacecraft operations.[41][54] Variability in active periods over decades arises primarily from nodal precession, the gradual rotation of a stream's orbital nodes due to gravitational influences from planets, particularly Jupiter. This precession shifts the timing of Earth's intersection with the stream by degrees per century, potentially altering peak dates and even causing temporary mismatches that reduce observed activity. Such changes can lead to fluctuations in shower strength, with some streams exhibiting irregular intensities until precession realigns them with Earth's orbit.[55][56] Newly identified meteoroid streams are initially classified as provisional, placed on working lists for ongoing observation and orbital analysis to confirm consistency and parameters. Provisional showers require multiple years of data to establish reliable radiant positions, velocities, and activity profiles before gaining established status, which demands well-defined orbital elements and predictable annual returns verified through international databases. This tracking process ensures only robust showers receive permanent IAU designations, distinguishing transient phenomena from persistent streams.[57][55][58]Scientific Origins and Evolution

Origin of Meteoroid Streams

Meteoroid streams primarily originate from the ejection of material from cometary nuclei, where the dominant mechanisms involve the sublimation of ices, sudden outbursts of activity, and fragmentation events. As a comet approaches the Sun, solar heating causes volatile ices to sublimate directly into gas, which entrains and accelerates embedded dust and ice particles away from the nucleus at velocities typically ranging from a few meters to tens of meters per second. This process releases meteoroids during each perihelion passage, with outbursts and fragmentations—often triggered by thermal stresses or internal pressures—contributing larger bursts of material, sometimes forming dense concentrations within the stream. Asteroids provide only minor contributions to meteoroid streams, primarily through rare collisional fragmentation in the inner solar system, which ejects rocky debris into similar orbits.[59][60][61] Upon ejection, these meteoroids are launched into orbits that closely resemble the parent body's elliptical path around the Sun, with slight perturbations from the asymmetric gas flow and radiation pressure influencing their trajectories. Smaller particles, particularly dust grains, experience greater acceleration due to radiation pressure, which can alter their semi-major axes and potentially eject them from bound orbits if they are sufficiently small. Initially, the released material forms a compact trail aligned with the comet's orbit, concentrated near perihelion; over multiple orbital periods, differential gravitational perturbations and non-gravitational forces cause the trail to disperse longitudinally into a broader filamentary stream, spanning thousands of kilometers in width but remaining narrow relative to the full orbital path. This evolution from trail to stream sets the stage for Earth to intersect the structure, producing observable meteor showers.[59][62][63] Parent bodies of meteoroid streams are identified through similarities in orbital elements, such as semi-major axis, eccentricity, and inclination, between the stream and known comets. For instance, the Perseid meteor shower is linked to Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle due to the close match in their orbital parameters, first noted in the 19th century. Jupiter-family comets (JFCs), which have periods less than about 20 years and are influenced by Jupiter's gravity, tend to produce more compact and variable streams owing to frequent planetary perturbations, while long-period comets (periods exceeding 200 years) generate more dispersed streams from their highly eccentric, nearly parabolic orbits originating in the Oort Cloud. These distinctions in parental dynamics influence the overall structure and longevity of the resulting streams.[64][65][66] At formation, meteoroid streams exhibit high initial density near the parent body's orbital path, with particles ranging in size from sub-millimeter dust grains to pebble-sized fragments up to several centimeters, depending on the ejection event's intensity. The concentration is greatest along the comet's recent trail, where recent ejections dominate, gradually thinning outward as older material spreads. This size distribution arises from the selective ejection processes, with finer grains more easily lifted by gas drag and larger ones requiring disruptive events like fragmentation.[59][67] Recent discoveries have highlighted streams formed from contemporary cometary disintegrations and asteroid collisions, providing insights into active formation processes. For example, observations of Comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) revealed its fragmentation into multiple pieces near perihelion in 2020, potentially seeding a new meteoroid stream detectable in future years. More recently, in November 2025, Comet C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) fragmented into multiple pieces shortly after perihelion, potentially contributing to a new meteoroid stream in coming years.[68] Similarly, analysis of the δ-Cancrid stream has identified potential parent near-Earth asteroids through orbital matching, suggesting collisional origins for some components, while a newly identified branch of the Taurid stream includes hazardous asteroids likely derived from recent disruptions. These findings underscore the ongoing production of streams from dynamic solar system events.[61][69]Dynamical Evolution of Streams

Meteoroid streams, originating from the repeated ejections of dust and debris from cometary nuclei, undergo significant dynamical changes post-formation due to interactions with the solar system's gravitational field and non-gravitational forces. These processes transform the initially narrow, compact trails of particles into broader, filamentary structures and, over extended periods, disperse them into the general sporadic meteoroid population. The evolution is driven primarily by planetary gravitational perturbations, solar radiation pressure, and Poynting-Robertson drag, which collectively alter orbital elements and particle trajectories on timescales ranging from thousands to hundreds of thousands of years.[70][63] In the early stages, shortly after ejection, meteoroids form a consolidated trail aligned closely with the parent's orbit, with limited dispersion due to initial velocity spreads of order 1-10 m/s. Over the first few orbital periods (typically decades to centuries), differential ejection and weak perturbations lead to the development of filaments—elongated substructures within the stream—where particles segregate by size and ejection timing. This filamentation enhances the potential for intense shower activity when Earth intersects these denser regions. However, over longer timescales of 10³ to 10⁵ years, progressive dispersion dominates, blending the stream into the isotropic sporadic background as particles achieve widely varying orbits.[71][72] Gravitational perturbations from major planets, especially Jupiter, are the primary dispersive agents for larger meteoroids (>1 mm), exerting close-encounter influences that modify semi-major axes, eccentricities, and inclinations through scattering and secular effects. Jupiter's dominant mass (about 10^{-3} solar masses) amplifies these changes, often stretching streams into ribbon-like configurations over millennia. Additionally, mean-motion resonances, such as 2:1 or 3:2 with Jupiter, can trap subsets of meteoroids in stable librating orbits, preserving stream coherence and periodically enhancing shower returns.[73][74] For smaller particles, non-gravitational forces accelerate dispersion: solar radiation pressure imparts an outward acceleration proportional to particle size and inversely to density (β ≈ 0.5-1 for sub-millimeter grains), inflating orbits and potentially hyperbolic ejection for the smallest sizes. Poynting-Robertson drag, resulting from the orbital motion-induced asymmetry in thermal re-radiation, applies a retrograde force that spirals particles inward, with decay times of ~10³ years for 100-μm grains and up to 10⁵ years for larger ones. These size-dependent effects cause rapid segregation, with small particles dominating early diffusion while larger ones persist longer under gravitational dominance.[75][76][77] The foundational mathematical framework treats unperturbed motion as Keplerian ellipses, governed by the two-body problem solution for position and velocity vectors under inverse-square gravity. Perturbations are then superimposed via first-order expansions, such as the Lagrange planetary equations, which describe differential changes in orbital elements (d a/dt, d e/dt, etc.) due to disturbing accelerations from planets or radiation. Resonant trapping arises when the stream's orbital period aligns commensurably with a planet's, leading to periodic energy exchanges that confine meteoroids to resonant libration zones rather than full chaotic diffusion.[78][79] Advanced modeling employs numerical N-body integrations to simulate stream evolution realistically, propagating ensembles of 10⁴-10⁶ test particles under full solar system ephemerides, including relativistic corrections and non-gravitational terms. Integrators like the Bulirsch-Stoer or symplectic methods in software packages such as REBOUND or the NASA Meteoroid Environment Office tools enable forward and backward integrations over 10⁴-10⁶ years, revealing filament structures and predicting intersections with planetary orbits. These simulations have successfully reproduced observed stream morphologies, such as the bifurcated Perseid filaments.[80][81][82] This evolutionary progression profoundly affects meteor shower characteristics, with dispersion reducing overall particle density and causing gradual weakening of annual intensities, as seen in streams older than ~10⁴ years where zenithal hourly rates (ZHR) decline by factors of 10-100. Conversely, resonant enhancements or incomplete mixing can produce cyclic intensity variations, including unpredictable outbursts when fresh filaments align with Earth's path, underscoring the need for ongoing dynamical models to forecast shower behavior.[83][54][84]Notable Meteor Showers

Perseids and Leonids

The Perseids meteor shower is associated with the periodic comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which has an orbital period of approximately 133 years and releases dust particles that Earth encounters annually.[85] The shower is active from mid-July to late August, reaching its peak around August 12-13, when the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) typically reaches about 100 meteors under ideal dark-sky conditions.[86][87] Meteors appear to radiate from a point in the constellation Perseus, near the star Eta Persei, and are known for their swift speeds of around 59 km/s, often producing bright trails.[88] Historical records show enhanced activity in years like 1993, when observed rates exceeded typical levels due to filamentary structures in the stream, though full storms are rare compared to other showers.[89] In contrast, the Leonids meteor shower originates from comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, which orbits the Sun every 33 years and sheds debris that causes Earth's annual encounter from early November to early December.[90] The peak occurs around November 17-18, with normal ZHRs varying from 10 to 15 meteors per hour, but the shower is notorious for dramatic variability, including intense storms every 33 years aligned with the comet's perihelion passage.[86][91] The radiant lies in the constellation Leo, near the star Gamma Leonis (Regulus), and meteors enter the atmosphere at high velocities of about 71 km/s, frequently appearing as bright fireballs with persistent trains.[90] Notable storms include the 1833 event, estimated at 10,000 to 60,000 meteors per hour across North America; the 1966 outburst, reaching up to 40 meteors per second (over 144,000 per hour) for brief periods; and the 2001 storms, which produced multiple peaks exceeding 1,000 meteors per hour due to encounters with dense filament trails.[91][41][92] The Perseids exhibit reliable, steady annual activity with year-to-year variations typically limited to 10-20%, making them one of the most predictable major showers for observers.[24] The Leonids, however, display cyclical storm behavior tied to the 33-year resonant orbital period of their parent comet, where Earth periodically crosses fresh, dense debris concentrations near the comet's path, leading to outbursts followed by quieter intervals.[93] This resonance results in the Leonids' irregular intensity, contrasting the Perseids' more diffuse, stable stream evolved over millennia.[94] The 1833 Leonid storm, in particular, had profound cultural impacts, inspiring religious interpretations such as depictions of the biblical "Day of Judgment" and folk accounts like the phrase "stars fell on Alabama," reflecting widespread awe and apocalyptic associations in 19th-century North American society.[95][96] Scientific studies of these showers have leveraged spacecraft and aerial platforms, particularly for the Leonids' unpredictable storms. NASA's Leonid Multi-Instrument Aircraft Campaign (MAC) in 1998-2002 used high-altitude aircraft equipped with cameras and spectrometers to capture thousands of meteors, measuring fluxes, velocities, and compositions during peaks like 2001, while satellites such as the Hubble Space Telescope adjusted orientations to avoid potential impacts.[97][98] Ground-based support from sites like Johnson Space Center documented storm dynamics, confirming risks to orbital assets from high-velocity particles.[99] Recent activity shows the Perseids maintaining consistent ZHRs around 100, with minor enhancements in years like 2016 from specific stream filaments.[87] The Leonids, after the 2001-2002 outbursts, have declined to baseline levels of about 12 meteors per hour, with no major storms expected until around 2034 due to the comet's orbital cycle dispersing recent debris.[97][100]Other Established Showers

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) Meteor Data Center maintains a list of 112 established meteor showers, many of which follow standard radiant-based naming conventions derived from their apparent points of origin in the sky.[101] Among these, several prominent annual events besides the Perseids and Leonids offer reliable displays, often with distinct characteristics tied to their parent bodies. The Geminids, peaking around December 13–14, are one of the strongest annual showers, with a zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of approximately 120 under ideal conditions.[50] Unlike most meteor showers, which originate from comets, the Geminids are associated with the asteroid 3200 Phaethon, a near-Earth object exhibiting comet-like activity possibly due to thermal processes or impacts releasing dust.[9] This non-cometary origin is unique among major showers, and observations indicate the stream's intensity has been gradually increasing over recent decades, potentially due to enhanced dust ejection from Phaethon.[102] The Quadrantids, active primarily in late December and early January, reach their peak on January 3–4 with a ZHR of about 120, but their activity is confined to a brief window of roughly eight hours due to the narrow filament of debris encountered by Earth.[103] The shower's radiant lies in the constellation Boötes, near the former location of the obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis, from which it derives its name. Its parent body is 2003 EH1, a small object classified as either an extinct comet or asteroid, suggesting a hybrid evolutionary path.[104] The Lyrids, peaking on April 21–22, produce a modest ZHR of around 18, with swift, bright meteors visible primarily from the Northern Hemisphere.[86] Their stream originates from the long-period comet C/1861 G1 (Thatcher), which orbits the Sun every 415 years and sheds dust particles that Earth encounters annually.[105] The shower occasionally experiences outbursts, such as the intense display recorded in 1803, when rates surged dramatically due to alignment with denser filamentary structures in the stream.[106] The Eta Aquariids and Orionids are twin showers both linked to Comet 1P/Halley, the famous periodic comet with a 76-year orbit. The Eta Aquariids peak in early May (around May 5–6), yielding a ZHR of 20–50, while the Orionids peak in late October (around October 21–22) with similar rates.[107][108] These showers feature fast-moving meteors (up to 66 km/s), producing long trails, and are more prominent in the Southern Hemisphere due to the radiants' positions near the celestial equator.[109] Overall, these established showers highlight the diversity of meteoroid streams, with about 16% of the IAU's catalog having confirmed parent bodies, often revealing insights into solar system dynamics.[110] Many radiants favor southern skies, enhancing visibility for observers in the Southern Hemisphere for equatorial and southern constellations.[111]Historical Context

Early Observations

Ancient civilizations documented meteor showers through annals and folklore, often interpreting them as omens or celestial phenomena. Chinese astronomical records, preserved in historical texts, describe one of the earliest known events on April 5, 687 BC, when "stars were not seen and stars fell like rain at midnight," likely referring to the Lyrid meteor shower.[112] Similarly, a significant Leonid storm was recorded by Chinese observers in 902 AD, marking one of the first detailed accounts of this annual shower's intense activity.[113] In Europe, Biblical passages alluded to falling stars, such as Revelation 6:13 stating "the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs," which later scholars interpreted as descriptions of meteor showers.[114] Cultural narratives imbued these events with spiritual meaning across societies. In Asian traditions, historical Korean, Chinese, and Japanese chronicles noted meteor showers in October, potentially including early observations of Draconid-like activity, often seen as portents in official histories.[115] These accounts highlight the showers' role in folklore, such as symbols of divine messages or natural cycles. Pre-telescopic observations faced significant challenges, including imprecise determination of the radiant point due to reliance on naked-eye sightings and the difficulty in recognizing periodicity without systematic long-term records spanning decades.[106] Without instruments, distinguishing individual showers from sporadic meteors was unreliable, limiting early understandings to qualitative descriptions rather than quantitative analysis. The 19th century marked a turning point with intensified scrutiny. The spectacular 1833 Leonid storm, observed across North America, featured estimates of 50,000 to 150,000 meteors per hour and was documented by astronomers like Denison Olmsted at Yale, who used newspaper reports to map the event's extent.[96] This display spurred further study, culminating in Giovanni Schiaparelli's 1866 Italian observations of both Perseid and Leonid streams, where he calculated their orbits and linked them to comets Tempel and Swift-Tuttle, respectively, establishing the foundational theory of meteoroid streams originating from cometary debris.[116][117] These efforts transitioned anecdotal records toward a scientific framework, confirming the periodic nature of major showers like the Perseids and Leonids.Modern Developments and Predictions

In the mid-20th century, radar technology revolutionized meteor shower observations by enabling all-sky monitoring independent of weather and daylight conditions. The Harvard Meteor Project, operational from 1952 to 1954 in New Mexico, utilized forward-scatter radar to detect thousands of faint meteors, providing the first systematic orbital data for streams and revealing velocity distributions that informed early dynamical models.[118] This approach complemented photographic methods, capturing meteors down to magnitudes of about +6, and established baselines for identifying stream associations.[119] Subsequent advancements included the establishment of global video networks, which offered precise trajectory measurements through triangulation. The International Meteor Organization (IMO), founded in 1988, pioneered coordinated video meteor observations, deploying low-light cameras to record meteors and compute orbits in real time.[120] These networks, now spanning multiple continents, have cataloged over a million trajectories, enhancing shower radiant and velocity profiles with sub-kilometer accuracy. In parallel, spacecraft missions provided in-situ data.[121] Predictive modeling gained prominence in the late 20th century, exemplified by forecasts for the Leonid meteor storms from 1998 to 2002. Using dynamical simulations of dust trails from Comet Tempel-Tuttle, researchers at NASA's Leonid Multi-Instrument Campaign accurately predicted peak zenith hourly rates exceeding 1,000 meteors per hour in 2001, validated by global observations that refined trail encounter timings.[122] Similarly, models anticipated the 2014 Camelopardalids outburst, where Earth crossed multiple dust trails from Comet 209P/LINEAR, producing rates up to 100 times normal and confirming outburst mechanisms through pre-event orbital integrations.[123] Modern predictive tools integrate numerical integrators and swarm simulations to assess shower evolution and hazards. The Marshall Space Flight Center Meteoroid Stream Model simulates particle ejection from parent bodies under planetary perturbations, forecasting stream dispersions over centuries and enabling risk assessments for spacecraft.[124] Swarm-based simulations further evaluate collision probabilities during storms, estimating that intense events like the 1993 Perseids posed up to 1% impact risk per 50 m² of satellite surface area at low Earth orbit altitudes, guiding maneuvers for assets like the International Space Station.[17] These tools draw on dynamical evolution principles to project long-term stream behaviors, such as filamentary structures that amplify outburst intensities.[125] Recent findings through 2025 have refined shower characterizations via advanced surveys. Enhanced dynamical modeling of the Geminids, linked to asteroid 3200 Phaethon, incorporates recent Parker Solar Probe dust measurements to simulate stream formation, predicting radiant drift and mass-dependent activity profiles that align with 2021-2024 observations.[126] The Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS) network, operational since 2010, has identified over 60 new minor showers by triangulating video data from global stations, including the February epsilon Virginids in 2013, expanding the International Astronomical Union list and revealing transient streams from young comets.[127] Looking ahead, forecasts indicate potential intensification of certain showers due to orbital alignments. The alpha Capricornids, associated with Comet 169P/NEAT, may strengthen significantly by 2200-2400 AD as nodal passages increase dust encounters, potentially elevating rates to storm levels based on multi-revolution simulations.[128] Such developments underscore broader space weather implications, where intense showers inject metallic ions into the ionosphere, perturbing electron densities and disrupting radio communications or GPS signals during peaks, as evidenced by enhanced sporadic E-layer formation during major events.[129] These risks highlight the need for integrated monitoring to mitigate impacts on satellite operations and aviation.[130]Extraterrestrial Analogues

Meteor Showers on Other Worlds