Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Molybdate

View on Wikipedia

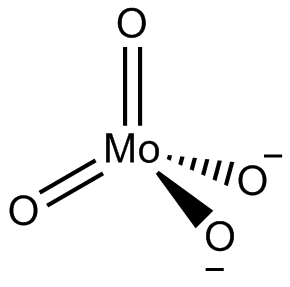

In chemistry, a molybdate is a compound containing an oxyanion with molybdenum in its highest oxidation state of +6: O−−Mo(=O)2−O−. Molybdenum can form a very large range of such oxyanions, which can be discrete structures or polymeric extended structures, although the latter are only found in the solid state. The larger oxyanions are members of group of compounds termed polyoxometalates, and because they contain only one type of metal atom are often called isopolymetalates.[1] The discrete molybdenum oxyanions range in size from the simplest MoO2−

4, found in potassium molybdate up to extremely large structures found in isopoly-molybdenum blues that contain for example 154 Mo atoms. The behaviour of molybdenum is different from the other elements in group 6. Chromium only forms the chromates, CrO2−

4, Cr

2O2−

7, Cr

3O2−

10 and Cr

4O2−

13 ions which are all based on tetrahedral chromium. Tungsten is similar to molybdenum and forms many tungstates containing 6 coordinate tungsten.[2]

Examples of molybdate anions

[edit]Examples of molybdate oxyanions are:

- MoO2−

4, in e.g. Na2MoO4 and the mineral powellite, CaMoO4; - Mo

2O2−

7, as hydrated ammonium dimolybdate. The anhydrous tetrabutylammonium salt of Mo

2O2−

7 is also known;[3] - Mo

3O2−

10 in the ethylenediamine salt;[4] - Mo

4O2−

13 in the potassium salt;[5] - Mo

5O2−

16 in the anilinium (C

6H

5NH+

3) salt;[6] - Mo

6O2−

19 (hexa-molybdate) in the tetramethylammonium salt;[7] - Mo

7O6−

24 in ammonium heptamolybdate, (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O;[8] - Mo

8O4−

26 in trimethylammonium salt.[1]

The naming of molybdates generally follows the convention of a prefix to show the number of Mo atoms present. For example, dimolybdate for 2 molybdenum atoms; trimolybdate for 3 molybdenum atoms, etc.. Sometimes the oxidation state is added as a suffix, such as in pentamolybdate(VI). The heptamolybdate ion, Mo

7O6−

24, is often called "paramolybdate".

Structure of molybdate anions

[edit]The smaller anions, MoO2−

4 and Mo

2O2−

7 feature tetrahedral centres. In MoO2−

4 the four oxygens are equivalent as in sulfate and chromate, with equal bond lengths and angles. Mo

2O2−

7 can be considered to be two tetrahedra sharing a corner, i.e. with a single bridging O atom.[1] In the larger anions molybdenum is generally, but not exclusively, 6 coordinate with edges or vertices of the MoO6 octahedra being shared. The octahedra are distorted, typical M-O bond lengths are:

- in terminal non bridging M–O approximately 1.7 Å

- in bridging M–O–M units approximately 1.9 Å

The Mo

8O4−

26 anion contains both octahedral and tetrahedral molybdenum and can be isolated in 2 isomeric forms, alpha and beta.[2]

The hexamolybdate image below shows the coordination polyhedra. The space filling model of the heptamolybdate image shows the close packed nature of the oxygen atoms in the structure. The oxide ion has an ionic radius of 1.40 Å, molybdenum(VI) is much smaller, 0.59 Å.[1] There are strong similarities between the structures of the molybdates and the molybdenum oxides, (MoO3, MoO2 and the "crystallographic shear" oxides, Mo9O26 and Mo10O29) whose structures all contain close packed oxide ions.[9]

-

(a) Hexamolybdate [Mo6O19]2− (b) Heptamolybdate [Mo7O24]6−

-

Ball and stick model of heptamolybdate

-

Heptamolybdate with space filling oxygen atoms

Equilibrium in aqueous solution

[edit]When MoO3, molybdenum trioxide is dissolved in alkali solution the simple MoO2−4 anion is produced:

As the pH is lowered, condensations ensue, with loss of water and the formation of Mo–O–Mo linkages. The stoichiometry leading to hexa-, hepta-, and octamolybdates are shown:[1][10]

Peroxomolybdates

[edit]Many peroxomolybdates are known. They tend to form upon treatment of molybdate salts with hydrogen peroxide. Notable is the monomer–dimer equilibrium:

Also known but unstable is [Mo(O2)4]2− (see potassium tetraperoxochromate(V)). Some related compounds find use as oxidants in organic synthesis.[11]

Tetrathiomolybdate

[edit]The red tetrathiomolybdate anion results when molybdate solutions are treated with hydrogen sulfide:

Like molybdate itself, MoS2−4 undergoes condensation in the presence of acids, but these condensations are accompanied by redox processes.

Industrial uses

[edit]Catalysis

[edit]Molybdates are widely used in catalysis. In terms of scale, the largest consumer of molybdate is as a precursor to catalysts for hydrodesulfurization, the process by which sulfur is removed from petroleum. Bismuth molybdates, nominally of the composition Bi9PMo12O52, catalyzes ammoxidation of propylene to acrylonitrile. Ferric molybdates are used industrially to catalyze the oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde.[12]

Corrosion inhibitors

[edit]Sodium molybdate has been used in industrial water treatment as a corrosion inhibitor. It was initially thought that it would be a good replacement for chromate, when chromate was banned for toxicity. However, molybdate requires high concentrations when used alone, therefore complementary corrosion inhibitors are generally added,[13] and is mainly used in high temperature closed-loop cooling circuits.[14] According to an experimental study, molybdate has been reported as an efficient biocide against microbiologically induced corrosion (MIC), where adding 1.5 mM MoO2−

4/day resulted in a 50 % decrease in the corrosion rate.[15]

Supercapacitors

[edit]Molybdates (especially FeMoO4, Fe2(MoO4)3, NiMoO4, CoMoO4 and MnMoO4) have been used as anode or cathode materials in aqueous capacitors.[16][17][18][19] Due to pseudocapacitive charge storage, specific capacitance up to 1500 F g−1 has been observed.[17]

Medicine

[edit]Radioactive molybdenum-99 in the form of molybdate is used as the parent isotope in technetium-99m generators for nuclear medicine imaging.[20]

Other

[edit]Nitrogen fixation requires molybdoenzymes in legumes (e.g., soybeans, acacia, etc.). For this reason, fertilizers often contain small amounts of molybdate salts. Coverage is typically less than a kilogram per acre.[12]

Molybdate chrome pigments are speciality but commercially available pigments.[12] Molybdate (usually in the form of potassium molybdate) is also used in the analytical colorimetric testing for the concentration of silica in solution, called the molybdenum blue method.[21] Additionally, it is used in the colorimetric analysis of phosphate concentration in association with the dye malachite green.

Molybdovanadate reagents contain both molybdate and vanadate ions. They are used in the determination of phosphate ion content in the analysis of wine and other fruit based products.[22]

Natural gems

[edit]Molybdate crystals as collected by gem enthusiasts with the world's best samples of crystalized molybdate coming from Madawaska Mine in Ontario (Canada).[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b c d Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-19957-5

- ^ V. W. Day; M. F. Fredrich; W. G. Klemperer; W. Shum (1977). "Synthesis and characterization of the dimolybdate ion, Mo

2O2−

7". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 99 (18): 6146. doi:10.1021/ja00460a074. - ^ Guillou N.; Ferey G. (August 1997). "Hydrothermal Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Anhydrous Ethylenediamine Trimolybdate (C

2H

10N

2)[Mo

3O

10]". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 132 (1): 224–227(4). Bibcode:1997JSSCh.132..224G. doi:10.1006/jssc.1997.7502. - ^ B. M. Gatehouse; P. Leverett (1971). "Crystal structure of potassium tetramolybdate, K

2Mo

4O

13, and its relationship to the structures of other univalent metal polymolybdates". J. Chem. Soc. A: 2107–2112. doi:10.1039/J19710002107. - ^ W. Lasocha; H. Schenk (1997). "Crystal Structure of Anilinium Pentamolybdate from Powder Diffraction Data. The Solution of the Crystal Structure by Direct Methods Package POWSIM". J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30 (6): 909–913. doi:10.1107/S0021889897003105.

- ^ S. Ghammami (2003). "The crystal and molecular structure of bis(tetramethylammonium) hexamolybdate(VI)". Crystal Research and Technology. 38 (913): 913–917. doi:10.1002/crat.200310112. S2CID 95078211.

- ^ Howard T. Evans jr.; Bryan M. Gatehouse; Peter Leverett (1975). "Crystal structure of the heptamolybdate(VI)(paramolybdate) ion, [Mo7O24]6−, in the ammonium and potassium tetrahydrate salts". J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. (6): 505–514. doi:10.1039/DT9750000505.

- ^ "Oxides: solid state chemistry" W.H. McCarroll, Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry Ed. R. Bruce King, John Wiley and Sons (1994) ISBN 0-471-93620-0

- ^ Klemperer, W. G. (1990). "Tetrabutylammonium Isopolyoxometalates". Inorganic Syntheses. Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 27. pp. 74–85. doi:10.1002/9780470132586.ch15. ISBN 9780470132586.

- ^ Dickman, Michael H.; Pope, Michael T. (1994). "Peroxo and Superoxo Complexes of Chromium, Molybdenum, and Tungsten". Chem. Rev. 94 (3): 569–584. doi:10.1021/cr00027a002.

- ^ a b c Roger F. Sebenik et al. "Molybdenum and Molybdenum Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology 2005; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_655

- ^ "Open Recirculating Cooling Systems - GE Water". gewater.com.

- ^ "Closed Recirculating Cooling Systems - GE Water". gewater.com.

- ^ "Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion in the Upstream Oil and Gas Industry".

- ^ Purushothaman, K. K.; Cuba, M.; Muralidharan, G. (2012-11-01). "Supercapacitor behavior of α-MnMoO4 nanorods on different electrolytes". Materials Research Bulletin. 47 (11): 3348–3351. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2012.07.027.

- ^ a b Senthilkumar, Baskar; Sankar, Kalimuthu Vijaya; Selvan, Ramakrishnan Kalai; Danielle, Meyrick; Manickam, Minakshi (2012-12-05). "Nano α-NiMoO4 as a new electrode for electrochemical supercapacitors". RSC Adv. 3 (2): 352–357. doi:10.1039/c2ra22743f. ISSN 2046-2069.

- ^ Cai, Daoping; Wang, Dandan; Liu, Bin; Wang, Yanrong; Liu, Yuan; Wang, Lingling; Li, Han; Huang, Hui; Li, Qiuhong (2013-12-26). "Comparison of the Electrochemical Performance of NiMoO4 Nanorods and Hierarchical Nanospheres for Supercapacitor Applications". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 5 (24): 12905–12910. doi:10.1021/am403444v. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 24274769.

- ^ Xia, Xifeng; Lei, Wu; Hao, Qingli; Wang, Wenjuan; Wang, Xin (2013-06-01). "One-step synthesis of CoMoO4/graphene composites with enhanced electrochemical properties for supercapacitors". Electrochimica Acta. 99: 253–261. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2013.03.131.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Medical Isotope Production Without Highly Enriched Uranium. (2009). "Molybdenum-99/Technetium-99m Production and Use". Medical Isotope Production without Highly Enriched Uranium. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

- ^ "ASTM D7126 – 15 Standard Test Method for On-Line Colorimetric Measurement of Silica". astm.org.

- ^ Amerine, Maynard A.; Amerine, Maynard Andrew; Joslyn, Maynard Alexander (1970-01-01). Table Wines: The Technology of Their Production. University of California Press. pp. 760–1. ISBN 978-0-520-01657-6.

- ^ McDougall, Raymond (2019-09-03). "Mineral Highlights from the Bancroft Area, Ontario, Canada". Rocks & Minerals. 94 (5): 408–419. doi:10.1080/00357529.2019.1619134. ISSN 0035-7529. S2CID 201298402.

![(a) Hexamolybdate [Mo6O19]2− (b) Heptamolybdate [Mo7O24]6−](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Polyederstrukturen_Molybd%C3%A4n.png/500px-Polyederstrukturen_Molybd%C3%A4n.png)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {MoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}{}+{}2\,\mathrm {NaOH} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}\mathrm {Na} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {MoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}{}+{}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/edb1483512e144b25c718969e55a8beb72b234fa)

![{\displaystyle {6\,[\mathrm {MoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}]{\vphantom {A}}^{2-}{}+{}10\,\mathrm {HCl} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}[\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{6}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{19}}]{\vphantom {A}}^{2-}{}+{}10\,\mathrm {Cl} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}{}+{}5\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6c7e460523b6c3300811b23faa0595a372be2c04)

![{\displaystyle {7\,\mathrm {MoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}{\vphantom {A}}^{2-}{}+{}8\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{7}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{24}}{\vphantom {A}}^{6-}{}+{}4\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/afaba606f12e3864281191ae9f992676a2e67395)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{7}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{24}}{\vphantom {A}}^{6-}{}+{}\mathrm {HMoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}{\vphantom {A}}^{-}{}+{}3\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{8}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{26}}{\vphantom {A}}^{4-}{}+{}2\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/17c29613abaef925e5d5c0cb65788e6bf90c7e91)

![{\displaystyle {[\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}(\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}(\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} ){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}]{\vphantom {A}}^{2-}{}\mathrel {\longrightleftharpoons } {}[\mathrm {Mo} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}(\mathrm {O} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}(\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} ){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}]{\vphantom {A}}^{2-}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/75670ef6b00c8c1655975c07b5436ee08ec092fe)

![{\displaystyle {[\mathrm {NH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}]{\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}[\mathrm {MoO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}]{}+{}4\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {S} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}[\mathrm {NH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}]{\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}[\mathrm {MoS} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}]{}+{}4\,\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9249a8f52bb6630839661353c724fc6650781ae4)