Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monoamine neurotransmitter

View on Wikipedia

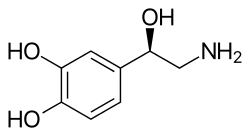

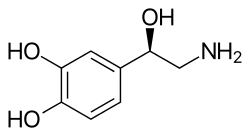

Monoamine neurotransmitters are neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that contain one amino group connected to an aromatic ring by a two-carbon chain (such as -CH2-CH2-). Examples are dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin.

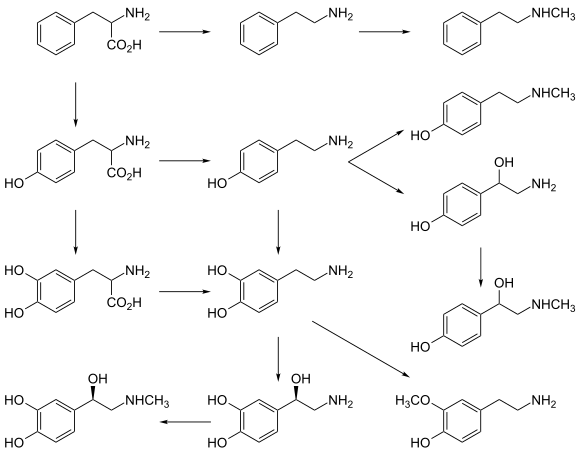

All monoamines are derived from aromatic amino acids like phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan by the action of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase enzymes. They are deactivated in the body by the enzymes known as monoamine oxidases which clip off the amine group.

Monoaminergic systems, i.e., the networks of neurons that use monoamine neurotransmitters, are involved in the regulation of processes such as emotion, arousal, and certain types of memory. It has also been found that monoamine neurotransmitters play an important role in the secretion and production of neurotrophin-3 by astrocytes, a chemical which maintains neuron integrity and provides neurons with trophic support.[1]

Drugs used to increase or reduce the effect of monoamine neurotransmitters are used to treat patients with psychiatric and neurological disorders, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease.[2]

Examples

[edit]- Classical monoamines

- Imidazoleamines:

- Catecholamines:

- Adrenaline (Ad; Epinephrine, Epi)

- Dopamine (DA)

- Noradrenaline (NAd; Norepinephrine, NE)

- Indolamines:

- Trace amines

- Phenethylamines (related to catecholamines):

- Tryptamine[10][8][9]

Specific transporter proteins called monoamine transporters that transport monoamines in or out of a cell exist. These are the dopamine transporter (DAT), serotonin transporter (SERT), and the norepinephrine transporter (NET) in the outer cell membrane and the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT1 and VMAT2) in the membrane of intracellular vesicles.[citation needed]

After release into the synaptic cleft, monoamine neurotransmitter action is ended by reuptake into the presynaptic terminal. There, they can be repackaged into synaptic vesicles or degraded by the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO), which is a target of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, a class of antidepressants.[citation needed]

Evolution

[edit]

Monoamine neurotransmitter systems occur in virtually all vertebrates, where the evolvability of these systems has served to promote the adaptability of vertebrate species to different environments.[12][13]

A recent computational investigation of genetic origins shows that the earliest development of monoamines occurred 650 million years ago and that the appearance of these chemicals, necessary for active or participatory awareness and engagement with the environment, coincides with the emergence of bilaterian or "mirror" body in the midst of (or perhaps in some sense catalytic of?) the Cambrian Explosion.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mele T, Čarman-Kržan M, Jurič DM (2010). "Regulatory role of monoamine neurotransmitters in astrocytic NT-3 synthesis". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 28 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.10.003. PMID 19854260. S2CID 25734591.

- ^ Kurian MA, Gissen P, Smith M, Heales SJ, Clayton PT (2011). "The monoamine neurotransmitter disorders: An expanding range of neurological syndromes". The Lancet Neurology. 10 (8): 721–33. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70141-7. PMID 21777827. S2CID 32271477.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Romero-Calderón R, Uhlenbrock G, Borycz J, Simon AF, Grygoruk A, Yee SK, Shyer A, Ackerson LC, Maidment NT, Meinertzhagen IA, Hovemann BT, Krantz DE (November 2008). "A glial variant of the vesicular monoamine transporter is required to store histamine in the Drosophila visual system". PLOS Genet. 4 (11) e1000245. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000245. PMC 2570955. PMID 18989452.

Unlike other monoamine neurotransmitters, the mechanism by which the brain's histamine content is regulated remains unclear. In mammals, vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs) are expressed exclusively in neurons and mediate the storage of histamine and other monoamines.

- ^ a b c d e f g Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase (MAO; EC 1.4.3.4) (Berry, 2004) (Fig. 2) ... It deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone ... Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut ...

Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate (Berry, 2004). Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life ... - ^ a b Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Khan MZ, Nawaz W (October 2016). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomed. Pharmacother. 83: 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. PMID 27424325.

- ^ a b c d e Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

In addition to the main metabolic pathway, TAs can also be converted by nonspecific N-methyltransferase (NMT) [22] and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) [23] to the corresponding secondary amines (e.g. synephrine [14], N-methylphenylethylamine and N-methyltyramine [15]), which display similar activities on TAAR1 (TA1) as their primary amine precursors...Both dopamine and 3-methoxytyramine, which do not undergo further N-methylation, are partial agonists of TAAR1 (TA1). ...

The dysregulation of TA levels has been linked to several diseases, which highlights the corresponding members of the TAAR family as potential targets for drug development. In this article, we focus on the relevance of TAs and their receptors to nervous system-related disorders, namely schizophrenia and depression; however, TAs have also been linked to other diseases such as migraine, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance abuse and eating disorders [7,8,36]. Clinical studies report increased β-PEA plasma levels in patients suffering from acute schizophrenia [37] and elevated urinary excretion of β-PEA in paranoid schizophrenics [38], which supports a role of TAs in schizophrenia. As a result of these studies, β-PEA has been referred to as the body's 'endogenous amphetamine' [39] - ^ Wainscott DB, Little SP, Yin T, Tu Y, Rocco VP, He JX, Nelson DL (January 2007). "Pharmacologic characterization of the cloned human trace amine-associated receptor1 (TAAR1) and evidence for species differences with the rat TAAR1". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 320 (1): 475–85. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.112532. PMID 17038507. S2CID 10829497.

- ^ Callier S, Snapyan M, Le Crom S, Prou D, Vincent JD, Vernier P (2003). "Evolution and cell biology of dopamine receptors in vertebrates". Biology of the Cell. 95 (7): 489–502. doi:10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00089-3. PMID 14597267. S2CID 18277786.

This "evolvability" of dopamine systems has been instrumental to adapt the vertebrate species to nearly all the possible environments.

- ^ Vincent JD, Cardinaud B, Vernier P (1998). "[Evolution of monoamine receptors and the origin of motivational and emotional systems in vertebrates]". Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 182 (7): 1505–14, discussion 1515–6. PMID 9916344.

These data suggest that a D1/beta receptor gene duplication was required to elaborate novel catecholamine psychomotor adaptive responses and that a noradrenergic system specifically emerged at the origin of vertebrate evolution.

- ^ Goulty M, Botton-Amiot G, Rosato E, Sprecher SG, Feuda R (2023-06-06). "The monoaminergic system is a bilaterian innovation". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 3284. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.3284G. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39030-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10244343. PMID 37280201.

External links

[edit]- Biogenic+monoamines at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Monoamine neurotransmitter

View on GrokipediaOverview and Classification

Definition

Monoamine neurotransmitters are a class of biogenic amines that function as chemical messengers in the nervous system, enabling interneuronal communication through synaptic transmission. These compounds are derived from single aromatic amino acids—tyrosine (for catecholamines), tryptophan (for serotonin), or histidine (for histamine)—each featuring a single amine group (-NH₂) that imparts their characteristic biochemical properties.[6][2] Their core structure consists of an aromatic ring attached to an ethylamine side chain, generally following the formula Ar-CH₂-CH₂-NH₂ (where Ar represents the aromatic ring), with minor variations such as additional hydroxyl groups in catecholamines like dopamine or the indole ring in serotonin. This structural configuration allows monoamines to be stored in synaptic vesicles and released via exocytosis in response to action potentials, distinguishing their mechanism of action in neural signaling.[7][6] Unlike amino acid neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate or GABA), which are unmodified amino acids acting primarily as fast ionotropic signals, or peptide neurotransmitters formed by chains of amino acids that often serve modulatory roles, monoamines are small organic molecules that typically engage G-protein-coupled receptors for slower, modulatory effects on postsynaptic excitability. Gaseous neurotransmitters like nitric oxide, by contrast, are non-stored diffusible signals without vesicular release. This positions monoamines as a unique subclass emphasizing vesicular storage and targeted synaptic release for neurotransmission.[2][8] The identification of monoamine neurotransmitters began in the early 20th century with the isolation of adrenaline (epinephrine) from adrenal glands in 1901 by Jokichi Takamine, initially recognized for its hormonal effects but later linked to neural functions. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) was established as a key neurotransmitter in the sympathetic nervous system by Ulf von Euler in 1946 through extraction from adrenergic nerves, providing foundational evidence for their role in chemical synaptic transmission.[9][10]Types and Examples

Monoamine neurotransmitters are broadly classified into catecholamines and indolamines, with histamine frequently grouped alongside them due to its similar biogenic amine structure and function, despite deriving from a different amino acid precursor.[6][11] Catecholamines, derived from tyrosine, encompass dopamine (DA; 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine), norepinephrine (NE; also known as noradrenaline, 4-(2-amino-1-hydroxyethyl)benzene-1,2-diol), and epinephrine (E; also known as adrenaline, 4-[(1R)-1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]benzene-1,2-diol).[12][13] Dopamine is primarily synthesized by dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain.[14] Norepinephrine is mainly produced by noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus of the pons.[15] Epinephrine, while predominantly functioning as a hormone from the adrenal medulla, is synthesized in limited central nervous system sites, including sparse neuronal groups expressing phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase.[6] Indolamines, derived from tryptophan, are represented by serotonin (5-HT; 5-hydroxytryptamine, 3-(2-aminoethyl)-1H-indol-5-ol), which is primarily synthesized in serotonergic neurons of the raphe nuclei spanning the brainstem.[16][17] Histamine (2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)ethanamine), derived from histidine, is classified as a monoamine and synthesized exclusively by histaminergic neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the posterior hypothalamus.[18][19]Biosynthesis and Metabolism

Synthesis Pathways

Monoamine neurotransmitters are synthesized from specific amino acid precursors through enzymatic pathways primarily occurring in the neuronal cytoplasm. The catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine) derive from L-tyrosine, serotonin from L-tryptophan, and histamine from L-histidine. These pathways involve rate-limiting hydroxylation steps and decarboxylation, with subsequent modifications for certain monoamines.[6][20] The biosynthesis of dopamine begins with L-tyrosine, which is hydroxylated to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting step requiring tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) as a cofactor. L-DOPA is then decarboxylated to dopamine by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), also known as DOPA decarboxylase, which uses pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) as a cofactor. TH activity is tightly regulated by phosphorylation via calcium- and cAMP-dependent kinases, as well as by feedback inhibition from catecholamines and transcriptional control.[20][6] Norepinephrine synthesis extends from dopamine, where dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) converts dopamine to norepinephrine in a reaction dependent on ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and copper as cofactors. This occurs within synaptic vesicles due to DBH localization. Epinephrine is further produced from norepinephrine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), which transfers a methyl group using S-adenosylmethionine as a cofactor; PNMT expression is induced by glucocorticoids in the adrenal medulla.[20] Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) is synthesized from L-tryptophan, which crosses the blood-brain barrier via the large neutral amino acid transporter and is hydroxylated to 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), the rate-limiting enzyme also requiring BH4. 5-HTP is then decarboxylated to serotonin by AADC, utilizing pyridoxal phosphate. TPH regulation depends on tryptophan availability from diet and transport, with TPH2 isoform predominant in the brain.[6] Histamine biosynthesis involves the decarboxylation of L-histidine to histamine by histidine decarboxylase (HDC), a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme. This single-step pathway occurs in histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus, with HDC regulation less understood but influenced by neuronal activity.[21] Following synthesis, monoamines are packaged into synaptic vesicles by vesicular monoamine transporters (VMAT1 and VMAT2), proton-dependent antiporters that sequester cytosolic monoamines using a vesicle proton gradient established by V-ATPase. VMAT2 predominates in the central nervous system, ensuring storage and protection from degradation.[22]Degradation Mechanisms

The degradation of monoamine neurotransmitters primarily occurs after their reuptake into presynaptic neurons via specific transporters for catecholamines and serotonin, which serves as the initial step in terminating synaptic signaling and preparing the molecules for enzymatic breakdown. The norepinephrine transporter (NET), dopamine transporter (DAT), and serotonin transporter (SERT) facilitate this reuptake; NET primarily handles norepinephrine, DAT targets dopamine, and SERT manages serotonin, thereby concentrating the monoamines intracellularly for subsequent metabolism.[23] A key enzyme in intraneuronal degradation is monoamine oxidase (MAO), a flavin-containing enzyme bound to the outer mitochondrial membrane that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of monoamines, producing corresponding aldehydes, hydrogen peroxide, and ammonia as byproducts. MAO exists in two isoforms: MAO-A, which exhibits higher affinity for serotonin and norepinephrine, and MAO-B, which preferentially metabolizes phenylethylamine and, to a lesser extent in humans, dopamine. This isoform-specific substrate selectivity helps regulate the turnover rates of different monoamines, with MAO activity preventing excessive accumulation that could lead to neurotoxicity from reactive intermediates.[24] In parallel, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) contributes to the degradation of catecholamines such as dopamine and norepinephrine through extraneuronal methylation, adding a methyl group to one of the hydroxyl groups on the catechol ring using S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor. Unlike the intraneuronal MAO, COMT is predominantly expressed in non-neuronal tissues and glial cells, acting on extracellular or reuptake-resistant catecholamines to form methylated metabolites like 3-methoxytyramine from dopamine. This process complements MAO by providing an alternative catabolic route, particularly in peripheral tissues.[25] The aldehydes generated by MAO, such as 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) from dopamine, are further metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes to less reactive carboxylic acids, mitigating potential cellular damage from these toxic intermediates. ALDH, including isoforms like ALDH1A1 (cytosolic) and ALDH2 (mitochondrial), catalyzes this NAD(P)+-dependent oxidation, converting DOPAL to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) in dopaminergic neurons. Impaired ALDH function can lead to aldehyde buildup, contributing to oxidative stress.[26] For histamine, termination of signaling occurs primarily through diffusion and low-affinity uptake via organic cation transporters (e.g., OCT3), rather than high-affinity reuptake, followed by intracellular degradation mainly by histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT), which methylates histamine to N-tele-methylhistamine using S-adenosylmethionine. This metabolite is then oxidized by MAO-B to N-methylimidazoleacetic acid. Extracellularly, diamine oxidase (DAO) can oxidize histamine to imidazole-4-acetaldehyde, which is further processed to imidazole-4-acetic acid. These pathways regulate histaminergic tone in the CNS, with HNMT predominant in the brain.[21][27] The major end metabolites of these degradation pathways include homovanillic acid (HVA) from dopamine (via sequential MAO, ALDH, and COMT action), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) from serotonin (primarily via MAO and ALDH), vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) from norepinephrine (involving MAO, ALDH, and COMT), and N-methylimidazoleacetic acid from histamine. These metabolites are often measured in cerebrospinal fluid or urine as biomarkers of monoamine turnover, reflecting the overall balance of synthesis and degradation in the nervous system.[28][29]Physiological Functions

Roles in the Central Nervous System

Monoamine neurotransmitters play critical roles in modulating various functions within the central nervous system (CNS), influencing brain regions involved in emotion, cognition, and behavior. These molecules, including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and histamine, are synthesized from amino acid precursors and released from specific neuronal clusters to exert widespread effects through diffuse projections.[30] Dopamine, originating primarily from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra, operates via distinct pathways in the CNS. The mesolimbic pathway projects to the nucleus accumbens and is central to reward processing and motivation, facilitating behaviors associated with pleasure and reinforcement learning.[31] The nigrostriatal pathway, extending to the dorsal striatum, regulates motor control by modulating basal ganglia circuits, ensuring coordinated movement and habit formation.[32] Additionally, the mesocortical pathway innervates the prefrontal cortex, supporting executive functions such as attention, working memory, and decision-making.[33] Serotonin, produced in the raphe nuclei of the brainstem, exerts influence through extensive projections to limbic structures like the amygdala and hippocampus. These connections are essential for mood regulation, promoting emotional stability and inhibiting impulsive responses.[34] Serotonergic neurons also contribute to the orchestration of sleep-wake cycles by modulating arousal states across cortical and subcortical regions.[35] Furthermore, serotonin impacts appetite control via hypothalamic pathways, balancing hunger signals and satiety to influence feeding behavior.[35] Norepinephrine, synthesized in the locus coeruleus (LC), provides broad innervation to the forebrain and brainstem, enhancing overall CNS vigilance. LC projections to the cortex and thalamus drive arousal and attention, optimizing sensory processing and task-oriented focus during demanding situations.[36] This system is also pivotal in the stress response, amplifying sympathetic activation to mobilize resources for threat detection and adaptive coping.[37] Histamine neurons, located exclusively in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) of the posterior hypothalamus, promote wakefulness through projections to the cortex, thalamus, and other arousal centers. TMN activity peaks during alert states, suppressing sleep-promoting circuits to maintain consciousness.[27] Histamine further synchronizes circadian rhythms by interacting with the suprachiasmatic nucleus, aligning daily physiological cycles with environmental cues.[38] Beyond individual actions, monoamines interact to fine-tune excitatory-inhibitory balance in the CNS, particularly by modulating glutamate and GABA transmission. For instance, serotonin and norepinephrine can enhance or suppress glutamatergic excitability in cortical networks, while dopamine influences GABAergic interneurons in striatal circuits, collectively stabilizing neural activity for adaptive behavior.[39]Roles in the Peripheral Nervous System

Monoamine neurotransmitters exert significant influence in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), primarily through the autonomic and enteric nervous systems, where they modulate visceral functions such as cardiovascular regulation, gastrointestinal motility, and immune responses. Unlike their roles in the central nervous system, peripheral monoamines often act as both neurotransmitters and hormones, released from neurons, chromaffin cells, and non-neuronal sources to maintain homeostasis.[40] Norepinephrine serves as the primary neurotransmitter of postganglionic sympathetic neurons, facilitating the "fight-or-flight" response by binding to adrenergic receptors on target organs. It induces vasoconstriction in arterioles of the skin, abdominal viscera, and kidneys via alpha-1 receptors, redirecting blood flow to skeletal muscles and vital organs. Additionally, norepinephrine increases heart rate and contractility through beta-1 receptors on cardiac tissue, enhancing overall cardiac output during stress.[41] Epinephrine, released from the adrenal medulla in response to sympathetic preganglionic stimulation, amplifies these effects systemically; it promotes glycogenolysis in the liver and further elevates heart rate via beta-2 receptors, preparing the body for acute physical demands.[41] Dopamine functions peripherally in the renal and gastrointestinal systems, acting as a local modulator rather than a direct sympathetic transmitter. In the kidneys, dopamine synthesized in proximal tubule cells activates D1-like receptors to increase renal blood flow and promote natriuresis by reducing vascular resistance and enhancing sodium excretion, thereby supporting fluid balance. In the enteric nervous system, dopamine regulates gastrointestinal motility through D2 receptors in the myenteric plexus, inhibiting peristalsis and secretion to fine-tune digestive processes.[42] Serotonin, predominantly produced in the periphery, plays a crucial role in hemostasis and gut function. Approximately 95% of the body's serotonin is synthesized by enterochromaffin cells in the intestinal mucosa, where it stimulates 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors to enhance gut motility, intestinal secretion, and colonic tone, facilitating propulsion and absorption. In the vascular system, serotonin stored in platelet granules is released during injury to promote platelet aggregation via 5-HT2A receptors, aiding clot formation and vasoconstriction at injury sites.[35] Histamine, while not exclusively neuronal in the PNS, is released from mast cells and enterochromaffin-like cells to mediate local responses. It stimulates gastric acid secretion by binding to H2 receptors on parietal cells in the stomach, increasing cyclic AMP to activate proton pumps and support digestion. In allergic contexts, histamine from degranulated mast cells acts on H1 receptors to induce vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and smooth muscle contraction in peripheral tissues, contributing to inflammatory defense mechanisms.[43] In the autonomic nervous system, monoamines like norepinephrine and epinephrine are central to sympathetic activation, promoting excitatory responses such as arousal and energy mobilization, whereas serotonin and dopamine predominate in the enteric nervous system, which interfaces with parasympathetic inputs to modulate inhibitory and propulsive gut activities. This division underscores their selective contributions to sympathetic versus parasympathetic balance in peripheral regulation.[40]Receptors and Signaling

Receptor Types

Monoamine neurotransmitters interact with a variety of receptor subtypes, primarily belonging to the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, with one exception being the ligand-gated ion channel 5-HT3 serotonin receptor. These receptors are classified based on their pharmacological properties, signaling mechanisms, and anatomical distributions, enabling diverse physiological responses. The main families correspond to dopamine, serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine/epinephrine (adrenergic), and histamine receptors.[44] Dopamine receptors are divided into two main subfamilies: D1-like (D1 and D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, and D4). The D1-like receptors couple to Gs proteins, leading to excitatory effects via increased cyclic AMP (cAMP) production, and are predominantly postsynaptic. In contrast, D2-like receptors couple to Gi/o proteins, resulting in inhibitory effects through decreased cAMP, and often function as presynaptic autoreceptors to regulate dopamine release. These subtypes are highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), particularly in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, with D1-like receptors more abundant in direct pathway medium spiny neurons and D2-like in indirect pathways.[45][46][47] Serotonin receptors comprise seven families (5-HT1 through 5-HT7), with most being GPCRs, except for the 5-HT3 receptor, which is a ligand-gated ion channel permeable to cations like sodium and calcium. The 5-HT1 family (subtypes 5-HT1A, 1B, 1D, 1E, 1F) generally couples to Gi/o proteins for inhibitory signaling; for instance, the 5-HT1A receptor acts as a presynaptic autoreceptor in raphe nuclei to inhibit serotonin release, while postsynaptic 5-HT1A modulates anxiety-related behaviors. The 5-HT2 family (2A, 2B, 2C) couples to Gq/11 for excitatory phospholipase C activation, with 5-HT2A being a key target for hallucinogenic effects due to its role in cortical pyramidal neurons. Other families include 5-HT4, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 (Gs-coupled, excitatory) and 5-HT3 (ionotropic, excitatory). Serotonin receptors are distributed across both CNS (e.g., hippocampus, cortex) and peripheral nervous system (PNS), including gastrointestinal and cardiovascular tissues.[48][44][49] Adrenergic receptors, activated by norepinephrine and epinephrine, are classified into alpha and beta subfamilies. Alpha-1 receptors (subtypes α1A, α1B, α1D) couple to Gq proteins, mediating excitatory responses via calcium mobilization, and are primarily postsynaptic in vascular smooth muscle. Alpha-2 receptors (α2A, α2B, α2C) couple to Gi/o for inhibitory effects, often presynaptic to inhibit norepinephrine release. Beta receptors (β1, β2, β3) couple to Gs proteins for stimulatory cAMP elevation; β1 predominates in cardiac tissue, β2 in bronchial and vascular smooth muscle, and β3 in adipose tissue. These receptors are widespread in the PNS, particularly in sympathetic nervous system targets like heart and blood vessels, with significant CNS expression in areas such as the locus coeruleus.[50][51][52] Histamine receptors include four subtypes, all GPCRs. The H1 receptor couples to Gq for excitatory signaling, playing a central role in allergic responses and smooth muscle contraction, and is postsynaptic in endothelial and neuronal cells. H2 couples to Gs for cAMP increase, primarily in gastric parietal cells to stimulate acid secretion. H3 receptors couple to Gi/o for inhibition, functioning mainly as presynaptic autoreceptors in the CNS to regulate histamine, dopamine, and serotonin release. H4 receptors also couple to Gi/o, mediating immune responses in eosinophils and mast cells. Histamine receptors are expressed in both CNS (e.g., H3 in hypothalamus) and PNS (e.g., H1 in skin and gut), with H1 and H2 more peripheral and H3/H4 bridging central and immune functions.[21][53][54]| Neurotransmitter | Receptor Subfamily/Subtypes | G-Protein Coupling | Key Distribution Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | D1-like (D1, D5) | Gs (excitatory) | Postsynaptic, mainly CNS (striatum) |

| D2-like (D2, D3, D4) | Gi/o (inhibitory) | Presynaptic autoreceptors, CNS (prefrontal cortex) | |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | 5-HT1 (A/B/D/E/F) | Gi/o (inhibitory) | Presynaptic (5-HT1A autoreceptor, CNS raphe), postsynaptic CNS/PNS |

| 5-HT2 (A/B/C) | Gq/11 (excitatory) | Postsynaptic, CNS cortex, PNS GI tract | |

| 5-HT3 | Ligand-gated ion channel | Postsynaptic, CNS/PNS (entorhinal cortex, gut) | |

| 5-HT4/6/7 | Gs (excitatory) | Postsynaptic, CNS hippocampus, PNS heart | |

| Norepinephrine/Epinephrine (Adrenergic) | α1 (A/B/D) | Gq (excitatory) | Postsynaptic, PNS vascular smooth muscle |

| α2 (A/B/C) | Gi/o (inhibitory) | Presynaptic, PNS sympathetic nerves, CNS locus coeruleus | |

| β (1/2/3) | Gs (stimulatory) | Postsynaptic, PNS heart (β1), lungs (β2), CNS/PNS | |

| Histamine | H1 | Gq (excitatory) | Postsynaptic, PNS (allergy sites), CNS (thalamus) |

| H2 | Gs (stimulatory) | Postsynaptic, PNS gastric mucosa | |

| H3 | Gi/o (inhibitory) | Presynaptic autoreceptor, CNS (hypothalamus) | |

| H4 | Gi/o (inhibitory) | Presynaptic/immune cells, PNS (eosinophils), low CNS |