Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

TAAR1

View on Wikipedia

| TAAR1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | TAAR1, TA1, TAR1, TRAR1, trace amine associated receptor 1, Trace amine receptor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 609333; MGI: 2148258; HomoloGene: 24938; GeneCards: TAAR1; OMA:TAAR1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) is a trace amine-associated receptor (TAAR) protein that in humans is encoded by the TAAR1 gene.[5]

TAAR1 is a primarily intracellular amine-activated Gs-coupled and Gq-coupled G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is primarily expressed in several peripheral organs and cells (e.g., the stomach, small intestine, duodenum, and white blood cells), astrocytes, and in the intracellular milieu within the presynaptic plasma membrane (i.e., axon terminal) of monoamine neurons in the central nervous system (CNS).[6][7][8][9]

TAAR1 is one of six functional human TAARs, which are so named for their ability to bind endogenous amines that occur in tissues at trace concentrations.[10][11] TAAR1 plays a significant role in regulating neurotransmission in dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin neurons in the CNS;[12][13][7][10] it also affects immune system and neuroimmune system function through different mechanisms.[14][15][16][17]

Endogenous ligands of the TAAR1 include trace amines, monoamine neurotransmitters, and certain thyronamines.[18][6] The trace amines β-phenethylamine, tyramine, tryptamine, and octopamine, the monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin, and the thyronamine 3-iodothyronamine (3-IT) are all agonists of the TAAR1 in different species.[18][6][19] Other endogenous agonists are also known.[18] A variety of exogenous compounds and drugs are TAAR1 agonists as well, including various phenethylamines, amphetamines, tryptamines, and ergolines, among others.[18] There are marked species differences in the interactions of ligands with the TAAR1, resulting in greatly differing affinities, potencies, and efficacies of TAAR1 ligands between species.[18] Many compounds that are TAAR1 agonists in rodents are much less potent or inactive at the TAAR1 in humans.[18]

A number of selective TAAR1 ligands have been developed, for instance the TAAR1 full agonist RO5256390, the TAAR1 partial agonist RO5263397, and the TAAR1 antagonists EPPTB and RTI-7470-44.[18][20] Selective TAAR1 agonists are used in scientific research, and a few TAAR1 agonists, such as ulotaront and ralmitaront, are being developed as novel pharmaceutical drugs, for instance to treat schizophrenia and substance use disorder.[20][21][22]

The TAAR1 was discovered in 2001 by two independent groups, Borowski et al. and Bunzow et al.[19][23]

Discovery

[edit]TAAR1 was discovered independently by Borowski et al. and Bunzow et al. in 2001. To find the genetic variants responsible for TAAR1 synthesis, they used mixtures of oligonucleotides with sequences related to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) of serotonin and dopamine to discover novel DNA sequences in rat genomic DNA and cDNA, which they then amplified and cloned. The resulting sequence was not found in any database and coded for TAAR1.[19][23] Further characterization of the functional role of TAAR1 and other receptors from this family was performed by other researchers including Raul Gainetdinov and his colleagues.[18]

Structure

[edit]TAAR1 shares structural similarities with the class A rhodopsin GPCR subfamily.[23] It has 7 transmembrane domains with short N and C terminal extensions.[24] TAAR1 is 62–96% identical with TAARs2-15, which suggests that the TAAR subfamily has recently evolved; while at the same time, the low degree of similarity between TAAR1 orthologues suggests that they are rapidly evolving.[19] TAAR1 shares a predictive peptide motif with all other TAARs. This motif overlaps with transmembrane domain VII, and its identity is NSXXNPXX[Y,H]XXX[Y,F]XWF. TAAR1 and its homologues have ligand pocket vectors that utilize sets of 35 amino acids known to be involved directly in receptor-ligand interaction.[11]

Gene

[edit]All human TAAR genes are located on a single chromosome spanning 109 kb of human chromosome 6q23.1, 192 kb of mouse chromosome 10A4, and 216 kb of rat chromosome 1p12. Each TAAR is derived from a single exon, except for TAAR2, which is coded by two exons.[11] The human TAAR1 gene is thought to be an intronless gene.[25]

Tissue distribution

[edit]

To date, TAAR1 has been identified and cloned in five different mammal genomes: human, mouse, rat, monkey, and chimpanzee. In rats, mRNA for TAAR1 is found at low to moderate levels in peripheral tissues like the stomach, kidney, intestines[26] and lungs, and at low levels in the brain.[19] Rhesus monkey Taar1 and human TAAR1 share high sequence similarity, and TAAR1 mRNA is highly expressed in the same important monoaminergic regions of both species. These regions include the dorsal and ventral caudate nucleus, putamen, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, locus coeruleus, amygdala, and raphe nucleus.[6][27] hTAAR1 has also been identified in human astrocytes.[6][14]

Outside of the human central nervous system, hTAAR1 also occurs as an intracellular receptor and is primarily expressed in the stomach, intestines,[26] duodenum,[26] pancreatic β-cells, and white blood cells.[9][26] In the duodenum, TAAR1 activation increases glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) release;[9] in the stomach, hTAAR1 activation has been observed to increase somatostatin (growth hormone-inhibiting hormone) secretion from delta cells.[9]

hTAAR1 is the only human trace amine-associated receptor subtype that is not expressed within the human olfactory epithelium.[28]

Location within neurons

[edit]TAAR1 is a primarily intracellular receptor expressed within the presynaptic terminal of monoamine neurons in humans and other animals.[7][10][29] In model cell systems, hTAAR1 has extremely poor membrane expression.[29] A method to induce hTAAR1 membrane expression has been used to study its pharmacology via a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer cAMP assay.[29]

Because TAAR1 is an intracellular receptor in monoamine neurons, exogenous TAAR1 ligands must enter the presynaptic neuron through a membrane transport protein[note 1] or be able to diffuse across the presynaptic membrane in order to reach the receptor and produce reuptake inhibition and neurotransmitter efflux.[10] Consequently, the efficacy of a particular TAAR1 ligand in producing these effects in different monoamine neurons is a function of both its binding affinity at TAAR1 and its capacity to move across the presynaptic membrane at each type of neuron.[10] The variability between a TAAR1 ligand's substrate affinity at the various monoamine transporters accounts for much of the difference in its capacity to produce neurotransmitter release and reuptake inhibition in different types of monoamine neurons.[10] E.g., a TAAR1 ligand which can easily pass through the norepinephrine transporter, but not the serotonin transporter, will produce – all else equal – markedly greater TAAR1-induced effects in norepinephrine neurons as compared to serotonin neurons.

A 2016 study found that most TAAR1 was expressed in intracellular membranes near the nucleus and that 2.3% of TAAR1 was expressed at the cell surface.[30] In addition, TAAR1 signaling via the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway was predominantly associated with cell-surface TAAR1.[30]

TAAR1 ligands have also been found to enter neurons by transporters other than the monoamine transporters.[31][32][33]

Receptor oligomers

[edit]TAAR1 forms GPCR oligomers with monoamine autoreceptors in neurons in vivo.[32][34] These and other reported TAAR1 hetero-oligomers include:

[note 2] in the TAAR1- D2sh example shows that TAAR1 can be located at cell membranes, and in the case of enterochromaffin cells in the gut epithelium, TAAR1 can be activated by high doses of dietary 'trace' amines, proximal to vesicles packed with catecholamines, impacting the vagal nerve system and CNS. This raises questions about where T1AM might find TAAR1 and cause similar unexpected nerve firing.

Ligands

[edit]| Trace amine-associated receptor 1 | |

|---|---|

| Transduction mechanisms | Gs, Gq, GIRKs, β-arrestin 2 |

| Primary endogenous agonists | Tyramine, β-phenylethylamine, octopamine, dopamine |

| Agonists | Full agonists: RO5166017, RO5256390, ulotaront, amphetamine, methamphetamine Partial agonists: RO5203648, RO5263397, RO5073012, ralmitaront |

| Neutral antagonists | RTI-7470-44 |

| Inverse agonists | EPPTB |

| Positive allosteric modulators | None known |

| Negative allosteric modulators | None known |

| External resources | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 364 |

| DrugBank | Q96RJ0 |

| HMDB | HMDBP10805 |

Agonists

[edit]Endogenous

[edit]The known endogenous agonists of the TAAR1 include trace amines like β-phenethylamine (PEA), monoamine neurotransmitters like dopamine, and thyronamines like 3-iodothyronamine (T1AM).[12]

Trace amines are endogenous amines which act as agonists at TAAR1 and are present in extracellular concentrations of 0.1–10 nM in the brain, constituting less than 1% of total biogenic amines in the mammalian nervous system.[36] Some of the human trace amines include tryptamine, phenethylamine (PEA), N-methylphenethylamine, p-tyramine, m-tyramine, N-methyltyramine, p-octopamine, m-octopamine, and synephrine. These share structural similarities with the three common monoamine neurotransmitters: serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Each ligand has a different potency, measured as increased cyclic AMP (cAMP) concentration after the binding event. The rank order of potency for the primary endogenous ligands at the human TAAR1 is: tyramine > β-phenethylamine > dopamine = octopamine.[6][19] Tryptamine and histamine also interact with the human TAAR1 with lower potency, whereas serotonin and norepinephrine have been found to be inactive.[18][19][37][23]

Thyronamines are molecular derivatives of thyroid hormone involved in endocrine system function. 3-Iodothyronamine (T1AM) is one of the most potent TAAR1 agonists yet discovered. It also interacts with a number of other targets.[13][38][39] Unlike the monoamine neurotransmitters and trace amines, T1A is not a monoamine transporter (MAT) substrate, although it does still weakly interact with the MATs.[38][40] Activation of TAAR1 by T1AM results in the production of large amounts of cAMP. This effect is coupled with decreased body temperature and cardiac output.

Other endogenous TAAR1 agonists include cyclohexylamine, isoamylamine, and trimethylamine, among others.[18][22][41]

Exogenous

[edit]- 2-Aminoindanes[18][37]

- 2-Aminoindane (2-AI) – a potent TAAR1 partial or full agonist in rodents, weaker TAAR1 full agonist in humans[18][37]

- 5-Iodo-2-aminoindane (5-IAI) – a potent TAAR1 partial or full agonist in rodents, weaker TAAR1 partial agonist in humans[18][37]

- MDAI – a potent TAAR1 full agonist in rodents, weaker TAAR1 partial agonist in humans[18][37]

- N-Methyl-2-AI (NM-2-AI) – a potent TAAR1 partial or full agonist in rodents, weaker TAAR1 partial agonist in humans[18][37]

- A-77636 – an experimental dopamine agonist[22]

- Amphetamines (α-methyl-β-phenethylamines)[42][43]

- 4-Fluoroamphetamine – a potent TAAR1 partial agonist in rodents, but much less potent in humans[18]

- 4-Hydroxyamphetamine – an amphetamine metabolite[23][43]

- Amphetamine – a potent TAAR1 near-full agonist in rodents, but much less potent in humans[37][7][9]

- Cathinone – weak rodent and human TAAR1 partial agonist[18]

- MDA – a potent TAAR1 partial agonist in rodents, but much less potent weak partial agonist in humans[37][43]

- MDMA – a moderate-efficacy TAAR1 partial agonist in rodents, but much less potent weak partial agonist in humans[37][43]

- Methamphetamine – a potent TAAR1 near-full agonist in rodents, but much less potent in humans[37][7][9]

- Phentermine – a weak human TAAR1 near-full agonist[44]

- Selegiline (L-deprenyl) – a weak mouse TAAR1 partial agonist[45]

- Solriamfetol – a wakefulness-promoting agent acting as a dual norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) and human TAAR1 agonist[46]

- AP163 – a TAAR1 agonist[47]

- Apomorphine – a dopamine agonist and antiparkinsonian agent, potent rodent TAAR1 agonist but not in humans[18][12][23][48]

- Asenapine – an atypical antipsychotic[22]

- Chlorpromazine – a dopamine antagonist and antipsychotic[12]

- Clonidine – an adrenergic agonist and antihypertensive agent, rodent and human TAAR1 agonist[18]

- Cyproheptadine – a serotonin antagonist[12][23]

- Ergolines and lysergamides[42][23]

- Bromocriptine – a dopamine agonist and antiparkinsonian agent[12][23]

- Dihydroergotamine – an antimigraine agent[42][23]

- Ergometrine (ergonovine) – an obstetric drug[42][23]

- Lisuride – a dopamine agonist and antiparkinsonian agent[42][23]

- Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) – a serotonergic psychedelic and TAAR1 weak partial agonist in rodents but not in humans[18][37][23][49]

- Metergoline – a prolactin inhibitor[12][23]

- Fenoldopam – a dopamine agonist and antihypertensive agent[22]

- Fenoterol – an adrenergic agonist[23]

- Guanabenz – an adrenergic agonist and antihypertensive agent, highly potent rodent and human TAAR1 agonist[18][22][50]

- Guanfacine – an adrenergic agonist and ADHD medication[22][51]

- Idazoxan – adrenergic antagonist, potent mouse TAAR1 agonist but much weaker in humans[18]

- Isoprenaline – an adrenergic agonist[52]

- LK00764 – a rodent and human TAAR1 agonist[53]

- MPTP – a monoaminergic neurotoxin[12][23]

- Naphazoline – an adrenergic agonist[23]

- Nomifensine – a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) and abandoned antidepressant[12][23]

- o-Phenyl-3-iodotyramine (o-PIT) – a rodent and human TAAR1 agonist[54][55][56]

- Oxymetazoline – an adrenergic agonist[23]

- Phentolamine – an adrenergic antagonist and rat TAAR1 agonist[12][23]

- Ralmitaront (RG-7906, RO6889450) – a TAAR1 partial agonist and investigational antipsychotic[57]

- RG-7351 – a TAAR1 partial agonist and abandoned experimental antidepressant[58][59]

- RG-7410 – a TAAR1 agonist and abandoned experimental antipsychotic[60][61]

- Ring-methoxylated phenethylamines and amphetamines[18]

- 2C-B – a serotonergic psychedelic, potent rat TAAR1 partial agonist but much weaker mouse and human TAAR1 partial agonist[18]

- 2C-E – a serotonergic psychedelic, potent rat TAAR1 partial agonist but much weaker mouse TAAR1 partial agonist and not in humans[18]

- 2C-T-7 – a serotonergic psychedelic, very high-affinity TAAR1 ligand in mice and rats but not in humans[18]

- DOB – a very weak human TAAR1 agonist[43]

- DOET – a weak human TAAR1 agonist[43]

- DOI – a rat TAAR1 agonist[23]

- DOM – a rhesus monkey TAAR1 agonist but not in humans[43]

- Mescaline – a serotonergic psychedelic, potent rodent TAAR1 partial agonist but not in humans[18]

- RO5073012 – a selective rodent and human TAAR1 low-efficacy partial agonist[18][62]

- RO5166017 – a selective rat and human TAAR1 near-full agonist but partial agonist in mice[18][55][62]

- RO5203648 – a selective rodent and human TAAR1 partial agonist[18][32][62]

- RO5256390 – a selective rat and human TAAR1 full agonist but partial agonist in mice[18][63]

- RO5263397 – a selective rodent and human TAAR1 partial agonist[18][32][62]

- S18616 – an adrenergic agonist[50]

- Synephrine – an adrenergic agonist[23]

- Tolazoline – an adrenergic antagonist and rat TAAR1 agonist[12][50][23]

- Tryptamines[18]

- Dimethyltryptamine – a serotonergic psychedelic, TAAR1 partial agonist in rodents but not in humans[18]

- Psilocin – a serotonergic psychedelic, TAAR1 partial agonist in rodents but not in humans[18]

- Ulotaront (SEP-363856, SEP-856) – a human TAAR1 full agonist and investigational antipsychotic[64][65]

Although amphetamine, methamphetamine, and MDMA are potent TAAR1 agonists in rodents, they are much less potent in terms of TAAR1 agonism in humans.[18][66][37][67] As examples, whereas amphetamine and methamphetamine have nanomolar potencies in activating the TAAR1 in rodents, they have micromolar potencies for TAAR1 agonism in humans.[18][66][37][43][67] MDMA shows very weak potency and efficacy as a human TAAR1 agonist and has been regarded as inactive.[18][66][37][68] Relatedly, it is not entirely clear whether agents like amphetamine and methamphetamine at typical doses produce significant TAAR1 agonism and associated effects in humans.[69][42][67][70] However, TAAR1 agonism and consequent effects by these drugs may be more relevant in the context of very high recreational doses.[42][67] TAAR1 activation has been found to have inhibitory effects on monoaminergic neurotransmission, and TAAR1 agonism by amphetamines may serve to auto-inhibit and constrain their effects.[71][69][72][54]

While some amphetamines are human TAAR1 agonists, many others are not.[37] As examples, most cathinones (β-ketoamphetamines), such as methcathinone, mephedrone, and flephedrone, as well as other amphetamines, including ephedrine, 4-methylamphetamine (4-MA), para-chloroamphetamine (PCA),[54] para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), 4-methylthioamphetamine (4-MTA), MDEA, MBDB, 5-APDB, and 5-MAPDB, are inactive as human TAAR1 agonists.[69][37] Many other drugs acting as monoamine releasing agents (MRAs) are also inactive as human TAAR1 agonists, for instance piperazines like benzylpiperazine (BZP), meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), and 3-trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP), as well as the alkylamine methylhexanamine (DMAA).[18][37][73] The negligible TAAR1 agonism with most cathinones might serve to enhance their effects and misuse potential as MRAs compared to their amphetamine counterparts.[69][72]

Monoaminergic activity enhancers (MAEs), such as selegiline, benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP), and phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP), have been claimed to act as TAAR1 agonists to mediate their MAE effects, but TAAR1 agonism for BPAP and PPAP has yet to be assessed or confirmed.[74][75] Selegiline is only a weak agonist of the mouse TAAR1, with dramatically lower potency than amphetamine or methamphetamine, and does not seem to have been assessed at the human TAAR1.[45][75]

Antagonists and inverse agonists

[edit]- Compound 22 – a very low-potency and non-selective TAAR1 antagonist[76][77]

- EPPTB (RO5212773) – a selective mouse TAAR1 inverse agonist but far less potent rat and human TAAR1 neutral antagonist[18][6][78]

- RTI-7470-44 – a potent and selective human TAAR1 neutral antagonist but far less potent mouse and rat TAAR1 antagonist[79][80]

A few other less well-known TAAR1 antagonists have also been discovered and characterized.[81][77][82][80]

RO5073012 is an antagonist-esque weak partial agonist of the rodent and human TAAR1 (Emax = 24–35%).[18][62][83][84] Similarly, MDA and MDMA are weak to very weak partial agonists or antagonists of the human TAAR1 (Emax = 11% and 26%, respectively), albeit with very low potency.[18][37][43]

It has been claimed that rasagiline may act as a TAAR1 antagonist, but TAAR1 interactions have yet to be assessed or confirmed for this agent.[75]

Function

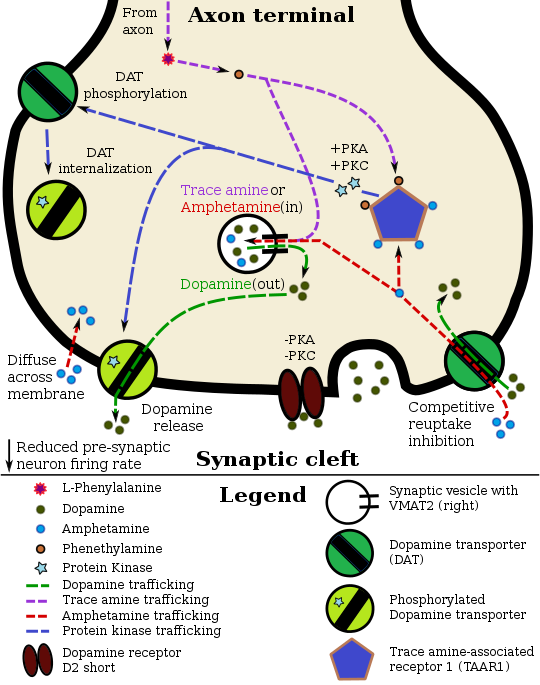

[edit]Phenethylamine and amphetamine in a TAAR1-localized dopamine neuron

|

Monoaminergic systems

[edit]Before the discovery of TAAR1, trace amines were believed to serve very limited functions. They were thought to induce noradrenaline release from sympathetic nerve endings and compete for catecholamine or serotonin binding sites on cognate receptors, transporters, and storage sites.[36] Today, they are believed to play a much more dynamic role by regulating monoaminergic systems in the brain.[92]

One of the downstream effects of active TAAR1 is to increase cAMP in the presynaptic cell via Gαs G-protein activation of adenylyl cyclase.[92][19][11] This alone can have a multitude of cellular consequences. A main function of the cAMP may be to up-regulate the expression of trace amines in the cell cytoplasm.[93] These amines would then activate intracellular TAAR1. Monoamine autoreceptors (e.g., D2 short, presynaptic α2, and presynaptic 5-HT1A) have the opposite effect of TAAR1, and together these receptors provide a regulatory system for monoamines.[10] Notably, amphetamine and trace amines possess high binding affinities for TAAR1, but not for monoamine autoreceptors.[10][7] The effect of TAAR1 agonists on monoamine transporters in the brain appears to be site-specific.[10] Imaging studies indicate that monoamine reuptake inhibition by amphetamine and trace amines is dependent upon the presence of TAAR1 co-localization in the associated monoamine neurons.[10] As of 2010, co-localization of TAAR1 and the dopamine transporter (DAT) has been visualized in rhesus monkeys, but co-localization of TAAR1 with the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and the serotonin transporter (SERT) has only been evidenced by messenger RNA (mRNA) expression.[10]

In neurons with co-localized TAAR1, TAAR1 agonists increase the concentrations of the associated monoamines in the synaptic cleft, thereby increasing post-synaptic receptor binding.[10] Through direct activation of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs), TAAR1 can reduce the firing rate of dopamine neurons, in turn preventing a hyper-dopaminergic state.[94][88][89] Amphetamine and trace amines can enter the presynaptic neuron either through DAT or by diffusing across the neuronal membrane directly.[10] As a consequence of DAT uptake, amphetamine and trace amines produce competitive reuptake inhibition at the transporter.[95][10] Upon entering the presynaptic neuron, these compounds activate TAAR1 which, through protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, causes DAT phosphorylation.[96] Phosphorylation by either protein kinase can result in DAT internalization (non-competitive reuptake inhibition), but PKC-mediated phosphorylation alone induces reverse transporter function (dopamine efflux).[10][97]

Immune system

[edit]Expression of TAAR1 on lymphocytes is associated with activation of lymphocyte immuno-characteristics.[16] In the immune system, TAAR1 transmits signals through active PKA and PKC phosphorylation cascades.[16] In a 2012 study, Panas et al. observed that methamphetamine had these effects, suggesting that, in addition to brain monoamine regulation, amphetamine-related compounds may have an effect on the immune system.[16] A recent paper showed that, along with TAAR1, TAAR2 is required for full activity of trace amines in PMN cells.[17]

Phytohaemagglutinin upregulates hTAAR1 mRNA in circulating leukocytes;[6] in these cells, TAAR1 activation mediates leukocyte chemotaxis toward TAAR1 agonists.[6] TAAR1 agonists (specifically, trace amines) have also been shown to induce interleukin 4 secretion in T-cells and immunoglobulin E (IgE) secretion in B cells.[6]

Astrocyte-localized TAAR1 regulates EAAT2 levels and function in these cells;[14] this has been implicated in methamphetamine-induced pathologies of the neuroimmune system.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]Low phenethylamine (PEA) concentration in the brain is associated with major depressive disorder,[19][36][98] and high concentrations are associated with schizophrenia.[98][99] Low PEA levels and under-activation of TAAR1 also appears to be associated with ADHD.[98][99][100] It is hypothesized that insufficient PEA levels result in TAAR1 inactivation and overzealous monoamine uptake by transporters, possibly resulting in depression.[19][36] Some antidepressants function by inhibiting monoamine oxidase (MAO), which increases the concentration of trace amines, which is speculated to increase TAAR1 activation in presynaptic cells.[19][11] Decreased PEA metabolism has been linked to schizophrenia, a logical finding considering excess PEA would result in over-activation of TAAR1 and prevention of monoamine transporter function. Mutations in region q23.1 of human chromosome 6 – the same chromosome that codes for TAAR1 – have been linked to schizophrenia.[11]

Medical reviews from February 2015 and 2016 noted that TAAR1-selective ligands have significant therapeutic potential for treating psychostimulant addictions (e.g., cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, etc.).[7][8] Despite wide distribution outside of the CNS and PNS, TAAR1 does not affect hematological functions and the regulation of thyroid hormones across different stages of ageing. Such data represent that future TAAR1-based therapies should exert little hematological effect and thus will likely have a good safety profile.[101]

Research

[edit]A large candidate gene association study published in September 2011 found significant differences in TAAR1 allele frequencies between a cohort of fibromyalgia patients and a chronic pain-free control group, suggesting this gene may play an important role in the pathophysiology of the condition; this possibly presents a target for therapeutic intervention.[102]

In preclinical research on rats, TAAR1 activation in pancreatic cells promotes insulin, peptide YY, and GLP-1 secretion;[103][non-primary source needed] therefore, TAAR1 is potentially a biological target for the treatment of obesity and diabetes.[103][non-primary source needed]

Lack of TAAR1 does not significantly affect sexual motivation and routine lipid and metabolic blood biochemical parameters, suggesting that future TAAR1-based therapies should have a favorable safety profile.[104]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin neurons, the primary membrane transporters are DAT, NET, and SERT respectively.[10]

- ^ TAAR1–D2sh is a presynaptic heterodimer which involves the relocation of TAAR1 from the intracellular space to D2sh at the plasma membrane, increased D2sh agonist binding affinity, and signal transduction through the calcium–PKC–NFAT pathway and G-protein independent PKB–GSK3 pathway.[7][35]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000146399 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000056379 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: TAAR1 trace amine associated receptor 1".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (20 February 2018). "Trace amine receptor: TA1 receptor". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

Tissue Distribution

CNS (region specific) & several peripheral tissues:

Stomach > amygdala, kidney, lung, small intestine > cerebellum, dorsal root ganglion, hippocampus, hypothalamus, liver, medulla oblongata, pancreas, pituitary gland, pontine reticular formation, prostate, skeletal muscle, spleen. ...

Leukocytes ...Pancreatic islet β cells ... Primary Tonsillar B Cells ... Circulating leukocytes of healthy subjects (upregulation occurs upon addition of phytohaemagglutinin).

Species: Human ...

In the brain (mouse, rhesus monkey) the TA1 receptor localises to neurones within the momaminergic pathways and there is emerging evidence for a modulatory role for TA1 on function of these systems. Co-expression of TA1 with the dopamine transporter (either within the same neurone or in adjacent neurones) implies direct/indirect modulation of CNS dopaminergic function. In cells expressing both human TA1 and a monoamine transporter (DAT, SERT or NET) signalling via TA1 is enhanced [26,48,50–51]. ...

Functional Assays ...

Mobilization of internal calcium in RD-HGA16 cells transfected with unmodified human TA1

Response measured: Increase in cytopasmic calcium ...

Measurement of cAMP levels in human cultured astrocytes.

Response measured: cAMP accumulation ...

Activation of leukocytes

Species: Human

Tissue: PMN, T and B cells

Response measured: Chemotactic migration towards TA1 ligands (β-Phenylethylamine, tyramine and 3-iodothyronamine), trace amine induced IL-4 secretion (T-cells) and trace amine induced regulation of T cell marker RNA expression, trace amine induced IgE secretion in B cells. - ^ a b c d e f g h Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). ""TAARgeting Addiction"-The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference". Drug Alcohol Depend. 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

TAAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for METH/AMPH and DA ... This original observation of TAAR1 and DA D2R interaction has subsequently been confirmed and expanded upon with observations that both receptors can heterodimerize with each other under certain conditions ... Additional DA D2R/TAAR1 interactions with functional consequences are revealed by the results of experiments demonstrating that in addition to the cAMP/PKA pathway (Panas et al., 2012) stimulation of TAAR1-mediated signaling is linked to activation of the Ca++/PKC/NFAT pathway (Panas et al.,2012) and the DA D2R-coupled, G protein-independent AKT/GSK3 signaling pathway (Espinoza et al., 2015; Harmeier et al., 2015), such that concurrent TAAR1 and DA DR2R activation could result in diminished signaling in one pathway (e.g. cAMP/PKA) but retention of signaling through another (e.g., Ca++/PKC/NFA)

- ^ a b Jing L, Li JX (August 2015). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1: A promising target for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 761: 345–352. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.019. PMC 4532615. PMID 26092759.

TAAR1 is largely located in the intracellular compartments both in neurons (Miller, 2011), in glial cells (Cisneros and Ghorpade, 2014) and in peripheral tissues (Grandy, 2007) ... Existing data provided robust preclinical evidence supporting the development of TAAR1 agonists as potential treatment for psychostimulant abuse and addiction. ... Given that TAAR1 is primarily located in the intracellular compartments and existing TAAR1 agonists are proposed to get access to the receptors by translocation to the cell interior (Miller, 2011), future drug design and development efforts may need to take strategies of drug delivery into consideration (Rajendran et al., 2010).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Berry MD, Gainetdinov RR, Hoener MC, Shahid M (December 2017). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. PMID 28723415.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e f Lindemann L, Ebeling M, Kratochwil NA, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Hoener MC (March 2005). "Trace amine-associated receptors form structurally and functionally distinct subfamilies of novel G protein-coupled receptors". Genomics. 85 (3): 372–385. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.11.010. PMID 15718104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pei Y, Asif-Malik A, Canales JJ (2016). "Trace Amines and the Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1: Pharmacology, Neurochemistry, and Clinical Implications". Front Neurosci. 10: 148. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00148. PMC 4820462. PMID 27092049.

- ^ a b Rutigliano G, Accorroni A, Zucchi R (2017). "The Case for TAAR1 as a Modulator of Central Nervous System Function". Front Pharmacol. 8 987. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00987. PMC 5767590. PMID 29375386.

T1AM has been reported to be a multitarget ligand, since it can also interact with other TAAR subtypes (particularly TAAR5), α2A- and β-adrenergic receptors, TRM8 calcium channels, and membrane amine transporters like dopamine transporter (DAT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) (reviewed by Hoefig et al., 2016). The affinity for these additional targets is substantially lower than the affinity for rat TAAR1, but the difficulties in assessing T1AM concentration at receptor level do not enable to reach a clear conclusion about their physiological relevance. As discussed below, the presence of non-TAAR targets is an important pitfall in the interpretation of experimental results obtained with the administration of natural TAAR1 ligands.

- ^ a b c d Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A (October 2014). "Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes". Neuropharmacology. 85: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.011. PMC 4315503. PMID 24950453.

TAAR1 overexpression significantly decreased EAAT-2 levels and glutamate clearance ... METH treatment activated TAAR1 leading to intracellular cAMP in human astrocytes and modulated glutamate clearance abilities. Furthermore, molecular alterations in astrocyte TAAR1 levels correspond to changes in astrocyte EAAT-2 levels and function.

- ^ Rogers TJ (2012). "The molecular basis for neuroimmune receptor signaling". J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7 (4): 722–724. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9398-4. PMC 4011130. PMID 22935971.

- ^ a b c d Panas MW, Xie Z, Panas HN, Hoener MC, Vallender EJ, Miller GM (December 2012). "Trace amine associated receptor 1 signaling in activated lymphocytes". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 7 (4): 866–876. doi:10.1007/s11481-011-9321-4. PMC 3593117. PMID 22038157.

- ^ a b Babusyte A, Kotthoff M, Fiedler J, Krautwurst D (March 2013). "Biogenic amines activate blood leukocytes via trace amine-associated receptors TAAR1 and TAAR2". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 93 (3): 387–394. doi:10.1189/jlb.0912433. PMID 23315425. S2CID 206996784.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Gainetdinov RR, Hoener MC, Berry MD (July 2018). "Trace Amines and Their Receptors". Pharmacol Rev. 70 (3): 549–620. doi:10.1124/pr.117.015305. PMID 29941461.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, et al. (July 2001). "Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (16): 8966–8971. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.8966B. doi:10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMC 55357. PMID 11459929.

- ^ a b Schwartz MD, Canales JJ, Zucchi R, Espinoza S, Sukhanov I, Gainetdinov RR (June 2018). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1: a multimodal therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric diseases". Expert Opin Ther Targets. 22 (6): 513–526. doi:10.1080/14728222.2018.1480723. hdl:11568/930006. PMID 29798691.

- ^ Liu J, Wu R, Li JX (January 2024). "TAAR1 as an emerging target for the treatment of psychiatric disorders". Pharmacol Ther. 253 108580. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108580. PMC 11956758. PMID 38142862.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shajan B, Bastiampillai T, Hellyer SD, Nair PC (2024). "Unlocking the secrets of trace amine-associated receptor 1 agonists: new horizon in neuropsychiatric treatment". Front Psychiatry. 15 1464550. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1464550. PMC 11565220. PMID 39553890.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S, Harrison LM, Zhang G, Quigley DI, et al. (December 2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 60 (6): 1181–1188. doi:10.1124/mol.60.6.1181. PMID 11723224.

- ^ Xie Z, Miller GM (November 2009). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 as a monoaminergic modulator in brain". Biochemical Pharmacology. 78 (9): 1095–1104. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.031. PMC 2748138. PMID 19482011.

- ^ "TAAR1". The Human Protein Atlas. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Bugda Gwilt K, González DP, Olliffe N, Oller H, Hoffing R, Puzan M, et al. (December 2019). "Actions of Trace Amines in the Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis via Trace Amine-Associated Receptor-1 (TAAR1)" (PDF). Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 40 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00772-7. PMC 11448870. PMID 31836967. S2CID 209339614.

- ^ Xie Z, Westmoreland SV, Bahn ME, Chen GL, Yang H, Vallender EJ, et al. (April 2007). "Rhesus monkey trace amine-associated receptor 1 signaling: enhancement by monoamine transporters and attenuation by the D2 autoreceptor in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 321 (1): 116–127. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.116863. PMID 17234900. S2CID 578835.

- ^ Liberles SD, Buck LB (August 2006). "A second class of chemosensory receptors in the olfactory epithelium". Nature. 442 (7103): 645–650. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..645L. doi:10.1038/nature05066. PMID 16878137. S2CID 2864195.

- ^ a b c Barak LS, Salahpour A, Zhang X, Masri B, Sotnikova TD, Ramsey AJ, et al. (September 2008). "Pharmacological characterization of membrane-expressed human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) by a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer cAMP biosensor". Molecular Pharmacology. 74 (3): 585–594. doi:10.1124/mol.108.048884. PMC 3766527. PMID 18524885.

- ^ a b Chen J, Underhill SM, Amara SG (2016). "Saturday Abstracts: 1012. Membrane Orientation, Cellular Localization and Signal Transduction of the Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". Biological Psychiatry. 79 (9): S281–S416 (S345–S345). doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.03.1410.

Background: The human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1) plays an important role in the regulation of monoamine neurotransmission and is a potential target for development of novel antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs. However, many aspects of the subcellular distribution and trafficking of hTAARI remain unknown. In this study, we investigated the membrane orientation, cellular localization and the signal transduction of hTAAR1 protein. Methods: A green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag was added to hTAAR1 for analysis of the orientation of hTAAR1 proteins in cells. An acceptor peptide (AP) tag for biotinylation was added to hTAARI for quantification of cell surface hTAARI. The function of hTAAR1 in protein kinase A (PKA) activation was analyzed using the hTAAR1 agonist amphetamine and a CRE-luciferase reporter system. Results: An anti-GFP antibody recognized the hTAAR1 fusion proteins only when GFP was at the N-terminus, but not the C-terminus in transfected HEK293. Only 2.3% (±0.7%) of N-terminal tagged hTAAR1 was detected at the cell surface. Most of the hTAAR1 proteins were localized in intracellular membranes near the nucleus. Amphetamine activated PKA similarly in the cells transfected with hTAAR1 only or with hTAAR1 and the dopamine transporter. Conclusions: hTAAR1 at the cell surface is oriented with the N-terminus in the extracellular space and the C-terminus in the cytosol. A small proportion of hTAAR1 proteins are at the cell surface, but most hTAAR1 proteins are localized within an intracellular membrane compartment. However, hTAAR1 signaling through PKA pathways occurs predominantly via the hTAAR1 at the cell surface.

- ^ Wu R, Liu J, Li JX (2022). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 and drug abuse". Behavioral Pharmacology of Drug Abuse: Current Status. Adv Pharmacol. Vol. 93. pp. 373–401. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2021.10.005. ISBN 978-0-323-91526-7. PMC 9826737. PMID 35341572.

A more recent study suggested that trace amines action is dependent on intracellular uptake by pentamidine-sensitive Na(+)-independent membrane transporters but not monoamine transporters (Gozal et al., 2014). Gozal EA, O'Neill BE, Sawchuk MA, Zhu H, Halder M, Chou CC, & Hochman S (2014). Anatomical and functional evidence for trace amines as unique modulators of locomotor function in the mammalian spinal cord. Front Neural Circuits, 8, 134. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00134

- ^ a b c d e Lam VM, Espinoza S, Gerasimov AS, Gainetdinov RR, Salahpour A (June 2015). "In-vivo pharmacology of Trace-Amine Associated Receptor 1". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 763 (Pt B): 136–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.026. PMID 26093041.

TAAR1 peripheral and immune localization/functions: It is important to note that in addition to the brain, TAAR1 is also expressed in the spinal cord (Gozal et al., 2014) and periphery (Revel et al., 2012c). It has been shown that TAAR1 is expressed and regulates immune function in rhesus monkey leukocytes (Babusyte et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2007; Panas et al., 2012). In granulocytes, TAAR1 is necessary for chemotaxic migration of cells towards TAAR1 agonists. In addition, TAAR1 signaling in B and T cells can trigger immunoglobulin and cytokine release, respectively (Babusyte et al., 2013). TAAR1 is also expressed in the islets of Langerhans, stomach and intestines based on LacZ staining patterns carried out on TAAR1-KO LacZ mice (Revel et al., 2012c). Interestingly, the administration of selective TAAR1 partial agonist RO5263397 reverses the side effect of weight gain observed with the antipsychotic olanzapine, indicating that peripheral TAAR1 signalling can regulate metabolic homeostasis (Revel et al., 2012b). ...

Monoamine transporters and SLC22A carrier subfamily transport TAAR1 ligand: Studies using the rhesus monkey TAAR1 have shown that this receptor interacts with the monoamine transporters DAT, SERT, and NET in HEK cells (Miller et al., 2005; Xie and Miller, 2007; Xie et al., 2007). It has been hypothesized that TAAR1 interaction with these transporters might provide a mechanism by which TAAR1 ligands can enter the cytoplasm and bind to TAAR1 in intracellular compartments. A recent study has shown that in rat neonatal motor neurons, trace-amine specific signalling requires the presence and function of the transmembrane solute carrier SLC22A but not that of monoamine transporters (DAT, SERT, and NET) (Gozal et al., 2014). Specifically, it was shown that addition of β-PEA, tyramine, or tryptamine induced locomotor like activity (LLA) firing patterns of these neurons in the presence of N-Methyl D-Aspartate. Temporally, it was found that the trace amine induction of LLA is delayed compared to serotonin and norepinephrine induced LLA, indicating the target site for the trace amines is not located on the plasma membrane and could perhaps be intracellular. Importantly, blocking of SLC22A with pentamidine abolished trace amine induced LLA, indicating that trace amine induced LLA does not act on receptors found on the plasma membrane but requires their transport to the cytosol by SLC22A for induction of LLA. - ^ Gozal EA, O'Neill BE, Sawchuk MA, Zhu H, Halder M, Chou CC, et al. (2014). "Anatomical and functional evidence for trace amines as unique modulators of locomotor function in the mammalian spinal cord". Front Neural Circuits. 8: 134. doi:10.3389/fncir.2014.00134. PMC 4224135. PMID 25426030.

TA actions on locomotor circuits did not require interaction with descending monoaminergic projections since evoked LLA was maintained following block of all Na(+)-dependent monoamine transporters or the vesicular monoamine transporter. Instead, TA (tryptamine and tyramine) actions depended on intracellular uptake via pentamidine-sensitive Na(+)-independent membrane transporters. Requirement for intracellular transport is consistent with the TAs having much slower LLA onset than serotonin and for activation of intracellular TAARs.

- ^ a b Dinter J, Mühlhaus J, Jacobi SF, Wienchol CL, Cöster M, Meister J, et al. (June 2015). "3-iodothyronamine differentially modulates α-2A-adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling". J. Mol. Endocrinol. 54 (3): 205–216. doi:10.1530/JME-15-0003. PMID 25878061.

Moreover, in ADRA2A/TAAR1 hetero-oligomers, the capacity of NorEpi to stimulate Gi/o signaling is reduced by co-stimulation with 3-T1AM. The present study therefore points to a complex spectrum of signaling modification mediated by 3-T1AM at different G protein-coupled receptors.

- ^ Harmeier A, Obermueller S, Meyer CA, Revel FG, Buchy D, Chaboz S, et al. (2015). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 activation silences GSK3β signaling of TAAR1 and D2R heteromers". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 25 (11): 2049–2061. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.08.011. PMID 26372541. S2CID 41667764.

Interaction of TAAR1 with D2R altered the subcellular localization of TAAR1 and increased D2R agonist binding affinity.

- ^ a b c d Zucchi R, Chiellini G, Scanlan TS, Grandy DK (December 2006). "Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands". British Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (8): 967–978. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706948. PMC 2014643. PMID 17088868.

Other biogenic amines are present in the central nervous system at very low concentrations in the order of 0.1–10 nm, representing <1% of total biogenic amines (Berry, 2004). For these compounds, the term 'trace amines' was introduced. Although somewhat loosely defined, the molecules generally considered to be trace amines include para-tyramine, meta-tyramine, tryptamine, β-phenylethylamine, para-octopamine and meta-octopamine (Berry, 2004) (Figure 2).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (April 2016). "In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1" (PDF). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 357 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID 26791601. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2025.

- ^ a b Hoefig CS, Zucchi R, Köhrle J (December 2016). "Thyronamines and Derivatives: Physiological Relevance, Pharmacological Actions, and Future Research Directions". Thyroid. 26 (12): 1656–1673. doi:10.1089/thy.2016.0178. hdl:11568/825783. PMID 27650974.

- ^ Biebermann H, Kleinau G (June 2020). "3-Iodothyronamine Induces Diverse Signaling Effects at Different Aminergic and Non-Aminergic G-Protein Coupled Receptors". Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 128 (6–07): 395–400. doi:10.1055/a-1022-1554. PMID 31698479.

- ^ Snead AN, Santos MS, Seal RP, Miyakawa M, Edwards RH, Scanlan TS (June 2007). "Thyronamines inhibit plasma membrane and vesicular monoamine transport". ACS Chem Biol. 2 (6): 390–398. doi:10.1021/cb700057b. PMID 17530732.

- ^ Xu Z, Guo L, Yu J, Shen S, Wu C, Zhang W, et al. (December 2023). "Ligand recognition and G-protein coupling of trace amine receptor TAAR1". Nature. 624 (7992): 672–681. Bibcode:2023Natur.624..672X. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06804-z. PMID 37935376.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grandy DK (December 2007). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1-Family archetype or iconoclast?". Pharmacol Ther. 116 (3): 355–390. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.007. PMC 2767338. PMID 17888514.

[AMPH and METH] promote DA release from synaptic storage vesicles into the cytoplasm (Partilla et al., 2006) and then into the extracellular space via DAT with an EC50 of 25 nM and a Ki uptake in rat synaptosomes of 34 nM (Rothman et al., 2001). These are drug concentrations approximately 20-30 fold lower than the EC50 values Reese et al. (2007) calculated for eliciting an in vitro functional response from rTAAR1 (0.8 μM). However, experienced METH users can typically consume gram quantities of drug per day (Kramer et al., 1967) and achieve peak blood concentrations of 100 μM (Derlet et al., 1989; Baselt, 2002; Peters et al., 2003). [...] The extracellular free concentration of METH surrounding relevant human dopaminergic synapses in the brain presumably is the relevant pharmacodynamic parameter, at least in part, underlying the desirable effects of the drug. Although this value is not known with certainty for humans METH serum levels typically represent one tenth of what is found in rat brain (Riviere et al., 2000). Consequently, when considered together with the human forensic evidence the in vitro results of Reese et al. (2007) are consistent with the interpretation that in vivo the human TAAR1 is likely to be a mediator of at least some of METH's effects.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorg Med Chem. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

- ^ Barak LS, Salahpour A, Zhang X, Masri B, Sotnikova TD, Ramsey AJ, et al. (September 2008). "Pharmacological characterization of membrane-expressed human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) by a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer cAMP biosensor". Mol Pharmacol. 74 (3): 585–594. doi:10.1124/mol.108.048884. PMC 3766527. PMID 18524885.

- ^ a b Wolinsky TD, Swanson CJ, Smith KE, Zhong H, Borowsky B, Seeman P, et al. (October 2007). "The Trace Amine 1 receptor knockout mouse: an animal model with relevance to schizophrenia". Genes Brain Behav. 6 (7): 628–639. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00292.x. PMID 17212650.

- ^ Gursahani H, Jolas T, Martin M, Cotier S, Hughes S, Macfadden W, et al. (2023). "Preclinical Pharmacology of Solriamfetol: Potential Mechanisms for Wake Promotion". CNS Spectrums. 28 (2): 222. doi:10.1017/S1092852923001396. ISSN 1092-8529.

In vitro functional studies showed agonist activity of solriamfetol at human, mouse, and rat TAAR1 receptors. hTAAR1 EC50 values (10–16 μM) were within the clinically observed therapeutic solriamfetol plasma concentration range and overlapped with the observed DAT/NET inhibitory potencies of solriamfetol in vitro. TAAR1 agonist activity was unique to solriamfetol; neither the WPA modafinil nor the DAT/NET inhibitor bupropion had TAAR1 agonist activity.

- ^ Krasavin M, Peshkov AA, Lukin A, Komarova K, Vinogradova L, Smirnova D, et al. (September 2022). "Discovery and In Vivo Efficacy of Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) Agonist 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-N-(3,5-dimethylphenyl)piperidine-1-carboxamide Hydrochloride (AP163) for the Treatment of Psychotic Disorders". Int J Mol Sci. 23 (19) 11579. doi:10.3390/ijms231911579. PMC 9569940. PMID 36232878.

- ^ Sukhanov I, Espinoza S, Yakovlev DS, Hoener MC, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR (October 2014). "TAAR1-dependent effects of apomorphine in mice". Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 17 (10): 1683–1693. doi:10.1017/S1461145714000509. PMID 24925023.

- ^ Wainscott DB, Little SP, Yin T, Tu Y, Rocco VP, He JX, et al. (January 2007). "Pharmacologic characterization of the cloned human trace amine-associated receptor1 (TAAR1) and evidence for species differences with the rat TAAR1". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 320 (1): 475–485. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.112532. PMID 17038507. S2CID 10829497.

Several series of substituted phenylethylamines were investigated for activity at the human TAAR1 (Table 2). A surprising finding was the potency of phenylethylamines with substituents at the phenyl C2 position relative to their respective C4-substituted congeners. In each case, except for the hydroxyl substituent, the C2-substituted compound had 8- to 27-fold higher potency than the C4-substituted compound. The C3-substituted compound in each homologous series was typically 2- to 5-fold less potent than the 2-substituted compound, except for the hydroxyl substituent. The most potent of the 2-substituted phenylethylamines was 2-chloro-β-PEA, followed by 2-fluoro-β-PEA, 2-bromo-β-PEA, 2-methoxy-β-PEA, 2-methyl-β-PEA, and then 2-hydroxy-β-PEA.

The effect of β-carbon substitution on the phenylethylamine side chain was also investigated (Table 3). A β-methyl substituent was well tolerated compared with β-PEA. In fact, S-(–)-β-methyl-β-PEA was as potent as β-PEA at human TAAR1. β-Hydroxyl substitution was, however, not tolerated compared with β-PEA. In both cases of β-substitution, enantiomeric selectivity was demonstrated.

In contrast to a methyl substitution on the β-carbon, an α-methyl substitution reduced potency by ~10-fold for d-amphetamine and 16-fold for l-amphetamine relative to β-PEA (Table 4). N-Methyl substitution was fairly well tolerated; however, N,N-dimethyl substitution was not. - ^ a b c Cichero E, Tonelli M (September 2017). "Targeting species-specific trace amine-associated receptor 1 ligands: to date perspective of the rational drug design process". Future Med Chem. 9 (13): 1507–1527. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0044. PMID 28791911.

- ^ Cichero E, Francesconi V, Casini B, Casale M, Kanov E, Gerasimov AS, et al. (November 2023). "Discovery of Guanfacine as a Novel TAAR1 Agonist: A Combination Strategy through Molecular Modeling Studies and Biological Assays". Pharmaceuticals. 16 (11): 1632. doi:10.3390/ph16111632. PMC 10674299. PMID 38004497.

- ^ Kleinau G, Pratzka J, Nürnberg D, Grüters A, Führer-Sakel D, Krude H, et al. (2011). "Differential modulation of Beta-adrenergic receptor signaling by trace amine-associated receptor 1 agonists". PLOS ONE. 6 (10) e27073. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...627073K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027073. PMC 3205048. PMID 22073124.

- ^ Krasavin M, Lukin A, Sukhanov I, Gerasimov AS, Kuvarzin S, Efimova EV, et al. (November 2022). "Discovery of Trace Amine Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) Agonist 2-(5-(4'-Chloro-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)ethan-1-amine (LK00764) for the Treatment of Psychotic Disorders". Biomolecules. 12 (11). doi:10.3390/biom12111650. PMC 9687812. PMID 36359001.

- ^ a b c Di Cara B, Maggio R, Aloisi G, Rivet JM, Lundius EG, Yoshitake T, et al. (November 2011). "Genetic deletion of trace amine 1 receptors reveals their role in auto-inhibiting the actions of ecstasy (MDMA)". J Neurosci. 31 (47): 16928–16940. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2502-11.2011. PMC 6623861. PMID 22114263.

- ^ a b Revel FG, Moreau JL, Gainetdinov RR, Bradaia A, Sotnikova TD, Mory R, et al. (May 2011). "TAAR1 activation modulates monoaminergic neurotransmission, preventing hyperdopaminergic and hypoglutamatergic activity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (20): 8485–8490. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8485R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103029108. PMC 3101002. PMID 21525407.

- ^ Hart ME, Suchland KL, Miyakawa M, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS (February 2006). "Trace amine-associated receptor agonists: synthesis and evaluation of thyronamines and related analogues". J Med Chem. 49 (3): 1101–1112. doi:10.1021/jm0505718. PMID 16451074.

- ^ Ågren R, Betari N, Saarinen M, Zeberg H, Svenningsson P, Sahlholm K (September 2023). "In Vitro Comparison of Ulotaront (SEP-363856) and Ralmitaront (RO6889450): Two TAAR1 Agonist Candidate Antipsychotics". Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 26 (9): 599–606. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyad049. PMC 10519813. PMID 37549917.

- ^ "RG 7351". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 5 November 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "Delving into the Latest Updates on RG-7351 with Synapse". Synapse. 19 September 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "RG 7410". AdisInsight. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Delving into the Latest Updates on RG-7410 with Synapse". Synapse. 19 September 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Wu R, Li JX (December 2021). "Potential of Ligands for Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) in the Management of Substance Use Disorders". CNS Drugs. 35 (12): 1239–1248. doi:10.1007/s40263-021-00871-4. PMC 8787759. PMID 34766253.

- ^ Revel FG, Moreau JL, Pouzet B, Mory R, Bradaia A, Buchy D, et al. (May 2013). "A new perspective for schizophrenia: TAAR1 agonists reveal antipsychotic- and antidepressant-like activity, improve cognition and control body weight". Mol Psychiatry. 18 (5): 543–556. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.57. PMID 22641180.

- ^ Achtyes ED, Hopkins SC, Dedic N, Dworak H, Zeni C, Koblan K (October 2023). "Ulotaront: review of preliminary evidence for the efficacy and safety of a TAAR1 agonist in schizophrenia". Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 273 (7): 1543–1556. doi:10.1007/s00406-023-01580-3. PMC 10465394. PMID 37165101.

- ^ Kuvarzin SR, Sukhanov I, Onokhin K, Zakharov K, Gainetdinov RR (July 2023). "Unlocking the Therapeutic Potential of Ulotaront as a Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 Agonist for Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Biomedicines. 11 (7): 1977. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11071977. PMC 10377193. PMID 37509616.

- ^ a b c Xu Z, Li Q (March 2020). "TAAR Agonists". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 40 (2): 257–272. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00774-5. PMC 11449014. PMID 31848873.

- ^ a b c d Reese EA, Bunzow JR, Arttamangkul S, Sonders MS, Grandy DK (April 2007). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 displays species-dependent stereoselectivity for isomers of methamphetamine, amphetamine, and para-hydroxyamphetamine". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 321 (1): 178–186. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.115402. PMID 17218486.

The EC50 of (+)-AMPH to release DA via DAT is 25 nM, with Ki uptake values in rat synaptosomes for this neurotransmitter of 34 nM at the DAT, concentrations approximately 20- to 30-fold lower than the EC50 values we calculated for eliciting an in vitro functional response from rTAAR1 (0.8 μM). Chronic METH abusers can typically consume gram quantities of drug per day (Kramer et al., 1967). [...] plasma concentrations of both drugs can reach into the high-micromolar range (Drummer and Odell, 2001; Baselt, 2002; Peters et al., 2003). Although the extracellular free concentration of METH around relevant human dopaminergic synapses presumably involved in producing desirable CNS effects is not known with certainty, in rats METH serum levels are typically 1/10 what is found in brain (Riviere et al., 2000). Forensic evidence indicates that experienced METH users can typically achieve peak blood concentrations of 100 μM (Baselt, 2002; Peters et al., 2003). Both isomers of METH were full agonists of h-rChTAAR1 over a range of EC50 values from 3.5 to ~15 μM, concentrations often exceeded in the blood of human METH addicts (Derlet et al., 1989). If TAAR1s, whether expressed in the CNS or periphery, are exposed to such concentrations, it is possible they could become functionally activated. [...] Given that the EC50 values for METH and AMPH activation of the h-rChTAAR1 in vitro are well below the concentrations frequently found in addicts, we suggest that TAAR1 might be a potential mediator of some of the effects of AMPH and METH in humans, including hyperthermia and stroke.

- ^ Dunlap LE, Andrews AM, Olson DE (October 2018). "Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine" (PDF). ACS Chem Neurosci. 9 (10): 2408–2427. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00155. PMC 6197894. PMID 30001118.

- ^ a b c d Kuropka P, Zawadzki M, Szpot P (May 2023). "A narrative review of the neuropharmacology of synthetic cathinones-Popular alternatives to classical drugs of abuse". Hum Psychopharmacol. 38 (3) e2866. doi:10.1002/hup.2866. PMID 36866677.

Another feature that distinguishes [synthetic cathinones (SCs)] from amphetamines is their negligible interaction with the trace amine associated receptor 1 (TAAR1). Activation of this receptor reduces the activity of dopaminergic neurones, thereby reducing psychostimulatory effects and addictive potential (Miller, 2011; Simmler et al., 2016). Amphetamines are potent agonists of this receptor, making them likely to self‐inhibit their stimulating effects. In contrast, SCs show negligible activity towards TAAR1 (Kolaczynska et al., 2021; Rickli et al., 2015; Simmler et al., 2014, 2016). [...] It is worth noting, however, that for TAAR1 there is considerable species variability in its interaction with ligands, and it is possible that the in vitro activity of [rodent TAAR1 agonists] may not translate into activity in the human body (Simmler et al., 2016). The lack of self‐regulation by TAAR1 may partly explain the higher addictive potential of SCs compared to amphetamines (Miller, 2011; Simmler et al., 2013).

- ^ Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). ""TAARgeting Addiction"--The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference". Drug Alcohol Depend. 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

That TAAR1 signaling is coupled to the inhibition of VTA DA neuron firing was a surprising finding. [...] earlier data suggested that TAAR1 activation leads to inhibition of DA uptake by DAT, promotion of DA efflux by DAT and DAT internalization which presumably would augment extracellular DA levels, whereas inhibition of DA neuronal firing rate would likely decrease extracellular DA levels, [...] this mismatch in expectations immediately attracted the attention of those trying to determine whether TAAR1 is a METH/AMPH and DA receptor in vivo as it is in vitro (Bunzow et al., 2001; Wainscott et al., 2007; Xie and Miller, 2009; Panas et al., 2012).

- ^ Espinoza S, Gainetdinov RR (2014). "Neuronal Functions and Emerging Pharmacology of TAAR1". Taste and Smell. Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 23. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 175–194. doi:10.1007/7355_2014_78. ISBN 978-3-319-48925-4.

Interestingly, the concentrations of amphetamine found to be necessary to activate TAAR1 are in line with what was found in drug abusers [3, 51, 52]. Thus, it is likely that some of the effects produced by amphetamines could be mediated by TAAR1. Indeed, in a study in mice, MDMA effects were found to be mediated in part by TAAR1, in a sense that MDMA auto-inhibits its neurochemical and functional actions [46]. Based on this and other studies (see other section), it has been suggested that TAAR1 could play a role in reward mechanisms and that amphetamine activity on TAAR1 counteracts their known behavioral and neurochemical effects mediated via dopamine neurotransmission.

- ^ a b Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, et al. (January 2013). "Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro". Br J Pharmacol. 168 (2): 458–470. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. PMC 3572571. PMID 22897747.

β-Keto-analogue cathinones also exhibited approximately 10-fold lower affinity for the TA1 receptor compared with their respective non-β-keto amphetamines. [...] Activation of TA1 receptors negatively modulates dopaminergic neurotransmission. Importantly, methamphetamine decreased DAT surface expression via a TA1 receptor-mediated mechanism and thereby reduced the presence of its own pharmacological target (Xie and Miller, 2009). MDMA and amphetamine have been shown to produce enhanced DA and 5-HT release and locomotor activity in TA1 receptor knockout mice compared with wild-type mice (Lindemann et al., 2008; Di Cara et al., 2011). Because methamphetamine and MDMA auto-inhibit their neurochemical and functional effects via TA1 receptors, low affinity for these receptors may result in stronger effects on monoamine systems by cathinones compared with the classic amphetamines.

- ^ Small C, Cheng MH, Belay SS, Bulloch SL, Zimmerman B, Sorkin A, et al. (August 2023). "The Alkylamine Stimulant 1,3-Dimethylamylamine Exhibits Substrate-Like Regulation of Dopamine Transporter Function and Localization". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 386 (2): 266–273. doi:10.1124/jpet.122.001573. PMC 10353075. PMID 37348963.

- ^ Harsing LG, Knoll J, Miklya I (August 2022). "Enhancer Regulation of Dopaminergic Neurochemical Transmission in the Striatum". Int J Mol Sci. 23 (15): 8543. doi:10.3390/ijms23158543. PMC 9369307. PMID 35955676.

- ^ a b c Harsing LG, Timar J, Miklya I (August 2023). "Striking Neurochemical and Behavioral Differences in the Mode of Action of Selegiline and Rasagiline". Int J Mol Sci. 24 (17) 13334. doi:10.3390/ijms241713334. PMC 10487936. PMID 37686140.

- ^ Lam VM, Mielnik CA, Baimel C, Beerepoot P, Espinoza S, Sukhanov I, et al. (2018). "Behavioral Effects of a Potential Novel TAAR1 Antagonist". Front Pharmacol. 9 953. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00953. PMC 6131539. PMID 30233365.

- ^ a b Lam VM, Rodríguez D, Zhang T, Koh EJ, Carlsson J, Salahpour A (2015). "Discovery of trace amine-associated receptor 1 ligands by molecular docking screening against a homology model". MedChemComm. 6 (12): 2216–2223. doi:10.1039/C5MD00400D. ISSN 2040-2503.

- ^ Bradaia A, Trube G, Stalder H, Norcross RD, Ozmen L, Wettstein JG, et al. (November 2009). "The selective antagonist EPPTB reveals TAAR1-mediated regulatory mechanisms in dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (47): 20081–20086. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620081B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906522106. PMC 2785295. PMID 19892733.

- ^ Scarano N, Espinoza S, Brullo C, Cichero E (July 2024). "Computational Methods for the Discovery and Optimization of TAAR1 and TAAR5 Ligands". Int J Mol Sci. 25 (15): 8226. doi:10.3390/ijms25158226. PMC 11312273. PMID 39125796.

On the other hand, HTS approaches [100] followed by structure-activity optimization allowed for the discovery of the hTAAR1 antagonist RTI-7470-44, endowed with a species-specificity preference over mTAAR1 (Figure 11A) [99]. RTI-7470-44 displayed good blood–brain barrier permeability, moderate metabolic stability, and a favorable preliminary off-target profile. In addition, RTI-7470-44 increased the spontaneous firing rate of mouse ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopaminergic neurons and blocked the effects of the known TAAR1 agonist RO5166017. [...] Figure 11. (A) Chemical structures of the available hTAAR1 agonists: EPPTB [98], RTI-7470-44 [99], and 4c [33], [...] RTI-7470-44: hTAAR1 IC50 = 0.0084 μM, mTAAR1 IC50 = 1.190 μM.

- ^ a b Decker AM, Brackeen MF, Mohammadkhani A, Kormos CM, Hesk D, Borgland SL, et al. (April 2022). "Identification of a Potent Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 Antagonist". ACS Chem Neurosci. 13 (7): 1082–1095. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00086. PMC 9730857. PMID 35325532.

While synthetic and endogenous hTAAR1 agonists have been developed (for a detailed review9), some with therapeutic potential for schizophrenia and substance abuse disorders,1,10–13 the discovery of TAAR1 antagonists remains surprisingly difficult. In the literature, the Hoffman-La Roche antagonist, [EPPTB], is the only fully characterized TAAR1 antagonist (Figure 1). [...] In the literature, a few additional antagonists have been identified (Cmpd 3, ET-54, ET-78),17–18 but all have weak potencies and none have been fully characterized at human, rat, and mouse TAAR1, making potency comparisons difficult (Figure 1; Cmpd 3: hTAAR1 IC50 = 9 μM, ET-54: rTAAR1 IC50 = 3 μM, ET-78: rTAAR1 IC50 = 4 μM).

- ^ Cichero E, Espinoza S, Franchini S, Guariento S, Brasili L, Gainetdinov RR, et al. (December 2014). "Further insights into the pharmacology of the human trace amine-associated receptors: discovery of novel ligands for TAAR1 by a virtual screening approach". Chem Biol Drug Des. 84 (6): 712–720. doi:10.1111/cbdd.12367. hdl:11380/1060933. PMID 24894156.

- ^ Decker AM, Mathews KM, Blough BE, Gilmour BP (January 2021). "Validation of a High-Throughput Calcium Mobilization Assay for the Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". SLAS Discov. 26 (1): 140–150. doi:10.1177/2472555220945279. PMID 32734809.

A few additional antagonists (Cmpd 3, ET-92, ET-78)46,47 have been identified in the literature, but none have been fully characterized and all suffer from potency issues (Cmpd 3: hTAAR1 IC50 = 9 µM, ET-92: rTAAR1 IC50 = 3 µM, ET-78: rTAAR1 IC50 = 4 µM). The discovery of our antagonists is groundbreaking, as our compounds are the most potent hTAAR1 antagonists identified to date (hTAAR1 IC50 = 206 and 281 nM).

- ^ Revel FG, Meyer CA, Bradaia A, Jeanneau K, Calcagno E, André CB, et al. (November 2012). "Brain-specific overexpression of trace amine-associated receptor 1 alters monoaminergic neurotransmission and decreases sensitivity to amphetamine". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (12): 2580–2592. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.109. PMC 3473323. PMID 22763617.

- ^ Galley G, Stalder H, Goergler A, Hoener MC, Norcross RD (August 2012). "Optimisation of imidazole compounds as selective TAAR1 agonists: discovery of RO5073012". Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 22 (16): 5244–5248. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.060. PMID 22795332.

- ^ a b Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC). ... AMPH release of DA from synapses requires both an action at VMAT2 to release DA to the cytoplasm and a concerted release of DA from the cytoplasm via "reverse transport" through DAT.

- ^ a b Quintero J, Gutiérrez-Casares JR, Álamo C (11 August 2022). "Molecular Characterisation of the Mechanism of Action of Stimulant Drugs Lisdexamfetamine and Methylphenidate on ADHD Neurobiology: A Review". Neurology and Therapy. 11 (4): 1489–1517. doi:10.1007/s40120-022-00392-2. PMC 9588136. PMID 35951288.

The active form of the drug has a central nervous system stimulating activity by the primary inhibition of DAT, NET, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (SLC18A2), among other targets, therefore regulating the reuptake and release of catecholamines (primarily NE and DA) on the synaptic cleft. ...

LDX can also promote the increase of DA in the synaptic cleft by activating protein TAAR1, which produces the efflux of monoamine NTs, mainly DA, from storage sites on presynaptic neurons. TAAR1 activation leads to intracellular cAMP signalling that results in PKA and PKC phosphorylation and activation. This PKC activation decreases DAT1, NET1 and SERT cell surface expression, intensifying the direct blockage of monoamine transporters by LDX and improving the neurotransmission imbalance in ADHD. - ^ Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (August 2016). "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia. 6 (3): 123–148. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMC 4850498. PMID 27141430.

Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.

- ^ a b Ledonne A, Berretta N, Davoli A, Rizzo GR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB (2011). "Electrophysiological effects of trace amines on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 5: 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00056. PMC 3131148. PMID 21772817.

inhibition of firing due to increased release of dopamine; (b) reduction of D2 and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibitory responses (excitatory effects due to disinhibition); and (c) a direct TA1 receptor-mediated activation of GIRK channels which produce cell membrane hyperpolarization.

- ^ a b mct (28 January 2012). "TAAR1". GenAtlas. University of Paris. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

" • tonically activates inwardly rectifying K(+) channels, which reduces the basal firing frequency of dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)" - ^ Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron. 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012). ... For example, AMPH increases extracellular glutamate in various brain regions including the striatum, VTA and NAc (Del Arco et al., 1999; Kim et al., 1981; Mora and Porras, 1993; Xue et al., 1996), but it has not been established whether this change can be explained by increased synaptic release or by reduced clearance of glutamate. ... DHK-sensitive, EAAT2 uptake was not altered by AMPH (Figure 1A). The remaining glutamate transport in these midbrain cultures is likely mediated by EAAT3 and this component was significantly decreased by AMPH

- ^ Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (9): 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

- ^ a b Rutigliano G, Accorroni A, Zucchi R (2017). "The Case for TAAR1 as a Modulator of Central Nervous System Function". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8 987. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00987. PMC 5767590. PMID 29375386.

Gs-mediated cAMP production was initially considered as the hallmark of TAAR1 activation, but we have now evidence that TAAR1 can also activate inward rectifying potassium channels and the β-arrestin 2 pathway, probably by Gs-independent pathways.

- ^ Xie Z, Miller GM (July 2009). "A receptor mechanism for methamphetamine action in dopamine transporter regulation in brain". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 330 (1): 316–325. doi:10.1124/jpet.109.153775. PMC 2700171. PMID 19364908.

- ^ Rutigliano G, Accorroni A, Zucchi R (2017). "The Case for TAAR1 as a Modulator of Central Nervous System Function". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8 987. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00987. PMC 5767590. PMID 29375386.

Gs-mediated cAMP production was initially considered as the hallmark of TAAR1 activation, but we have now evidence that TAAR1 can also activate inward rectifying potassium channels and the β-arrestin 2 pathway, probably by Gs-independent pathways.

- ^ Caye A, Swanson JM, Coghill D, Rohde LA (2019). "Treatment strategies for ADHD: an evidence-based guide to select optimal treatment". Molecular Psychiatry. 24 (3): 390–408. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0116-3. ISSN 1476-5578. PMID 29955166.

Amphetamines have at least three mechanisms of action: (1) they are transported by the monoamine transporters DAT and NET, thus competing with those neurotransmitters and decreasing their reuptake in the synapse; (2) They also cause trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) to phosphorylate DAT. The phosphorylated DAT is either internalized into the presynaptic neuron and ceases transport or inverses the efflux of dopamine; (3) they enter the presynaptic monoamine vesicle and cause efflux of neurotransmitters off the vesicle, which in turn augments the efflux towards the synapse. These mechanisms are more studied and established for dopamine neurotransmission, but are thought to occur similarly for norepinephrine.

- ^ Dalvi S, Bhatt LK (2025). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1): an emerging therapeutic target for neurodegenerative, neurodevelopmental, and neurotraumatic disorders". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 398 (5): 5057–5075. doi:10.1007/s00210-024-03757-6. PMID 39738834.

The mechanism of efflux of monoamines in the synapse is due to the activation of TAAR1 by TAs or drugs belonging to the amphetamine class which increases the level of cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate) followed by an increase in the level of PKA (protein kinase A) and PKC (protein kinase C) phosphorylation. This reverses the monoamine transport by reversing the direction of monoamine transporters.

- ^ Maguire JJ, Parker WA, Foord SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Davenport AP (March 2009). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXXII. Recommendations for trace amine receptor nomenclature". Pharmacological Reviews. 61 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1124/pr.109.001107. PMC 2830119. PMID 19325074.

- ^ a b c Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

The dysregulation of TA levels has been linked to several diseases, which highlights the corresponding members of the TAAR family as potential targets for drug development. In this article, we focus on the relevance of TAs and their receptors to nervous system-related disorders, namely schizophrenia and depression; however, TAs have also been linked to other diseases such as migraine, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance abuse and eating disorders [7,8,36]. Clinical studies report increased β-PEA plasma levels in patients suffering from acute schizophrenia [37] and elevated urinary excretion of β-PEA in paranoid schizophrenics [38], which supports a role of TAs in schizophrenia. As a result of these studies, β-PEA has been referred to as the body's 'endogenous amphetamine' [39]