Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Theory of multiple intelligences

View on Wikipedia

The theory of multiple intelligences (MI) posits that human intelligence is not a single general ability but comprises various distinct modalities, such as linguistic, logical-mathematical, musical, and spatial intelligences.[1] Introduced in Howard Gardner's book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983), this framework has gained popularity among educators who accordingly develop varied teaching strategies purported to cater to different student strengths.[2][3]

Despite its educational impact, MI has faced criticism from the psychological and scientific communities. A primary point of contention is Gardner's use of the term "intelligences" to describe these modalities. Critics argue that labeling these abilities as separate intelligences expands the definition of intelligence beyond its traditional scope, leading to debates over its scientific validity.[4]

While empirical research often supports a general intelligence factor (g-factor),[5] Gardner contends that his model offers a more nuanced understanding of human cognitive abilities.[6] This difference in defining and interpreting "intelligence" has fueled ongoing discussions about the theory's scientific robustness.

Separation criteria

[edit]Beginning in the late 1970s, using a pragmatic definition, Howard Gardner surveyed several disciplines and cultures around the world to determine skills and abilities essential to human development and culture building. He subjected candidate abilities to evaluation using eight criteria that must be substantively met to warrant their identification as an intelligence. Furthermore, the intelligences need to be relatively autonomous from each other, and composed of subsets of skills that are highly correlated and coherently organized.

In 1983, the field of cognitive neuroscience was embryonic but Gardner was one of the early psychological theorists to describe direct links between brain systems and intelligence. Likewise the field of educational neuroscience was yet to be conceived. Since Frames of Mind was published (1983) the terms cognitive science and cognitive neuroscience have become standard in the field with extensive libraries of scholarly and scientific papers and textbooks.[1] Thus it is essential to examine neuroscience evidence as it pertains to MI validity.

Gardner defined intelligence as "a biopsychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture."[1]

This definition is unique for several reasons that account for MI theory's broad appeal to educators as well as its rejection by mainstream psychologists who are rooted in the traditional conception of intelligence as an abstract, logical capacity.[7] A fundamental element for each intelligence is a framework of clearly defined levels of skill, complexity and accomplishment. One model that fits with the MI framework is Bloom’s taxonomy where each intelligence can be delineated along different levels, ranging from basic knowledge up to their highest levels of analysis / synthesis.[8][9]

MI is also unique because it gives full appreciation for the impact and interactions - via symbol systems - between the individual’s cognitions and their particular culture. As Gardner states,

The multiple intelligences commence as a set of uncommitted neurobiological potentials. They become crystallized and mobilized by the communication that takes place among human beings and, especially, by the systems of meaning-making that already exist in a given culture.[10]

Unlike traditional practices beginning in the 19th century,[11] MI theory is not built on the statistical analyses of psychometric test data searching for factors that account for academic achievement. Instead, Gardner employs a multi-disciplinary, cross-cultural methodology to evaluate which human capacities fit into a comprehensive model of intelligence. Eight criteria accounting for advances in neuroscience and the influence of cultural factors are used to qualify a capacity as an intelligence. These criteria are drawn from a more extensive database than what was acceptable and available to researchers in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Evidence is gathered from a variety of disciplines including psychology, neurology, biology, sociology, and anthropology as well as the arts and humanities. If a candidate faculty meets this set of criteria reasonably well then it can qualify as an intelligence. If it does not, then it is set aside or reconceptualized.[12]

Criteria for each type of intelligence

[edit]The eight criteria can be grouped into four general categories:

- biology (neuroscience and evolution)

- analysis (core operations and symbol systems)

- psychology (skill development, individual differences)

- psychometrics (psychological experiments and test evidence)

The criteria briefly described are:

- potential for brain isolation by brain damage

- place in evolutionary history

- presence of core operations

- susceptibility to encoding (symbolic expression)

- a distinct developmental progression

- the existence of savants, prodigies and other exceptional people

- support from experimental psychology

- support from psychometric findings

This scientific method resembles the process used by astronomers to determine which celestial bodies to classify as a planet versus dwarf planet, star, comet, etc.[citation needed]

Forms of intelligences

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

In Frames of Mind and its sequels, Howard Gardner describes eight intelligences that can be expressed in everyday life in a variety of ways referred to as domains, skills, competencies, or talents.[13] Like describing a multi-layer cake, the complexity depends upon how you slice the cake. One model integrates the eight intelligences with Sternberg's triarchic theory, so each intelligence is actively expressed in three ways: (1) creative, (2) academic / analytical and (3) practical thinking.[14][15] In this analogy each of the eight cake layers are divided into three segments with different expressions sharing a central core. Exemplar professions and adult roles requiring specific intelligences are described along with their core skills and potential deficits. Several references to exemplar neuroscientific studies are also provided for each of the eight intelligences. Furthermore, some have suggested that the 'intelligences' refer to talents, personality, or ability rather than a distinct form of intelligence.[16]

The two intelligences that are most associated with the traditional I.Q. or general intelligence are the linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences. Some intelligence models and tests also include visual-spatial intelligence as a third element.

Musical

[edit]This area of intelligence includes sensitivity to the sounds, rhythms, pitch, and tones of music. People with musical intelligence normally may be able to sing, play musical instruments, or compose music. They have high sensitivity to pitch, meter, melody and timbre.[17] Musical intelligence includes cognitive elements that contribute to a person’s success and quality of life. There is a strong relationship between music and emotions as evidenced in both popular and classical music spheres. Neuroscience investigators continue to investigate the interaction between music and cognitive performances.[18] Music is deeply rooted in human evolutionary history (Paleolithic bone flute) and culture (every country on Earth has a national anthem'[citation needed]) and our personal lives (many important life events are associated with particular types of music, like birthday songs, wedding songs, funeral dirges, etc.).

Deficits in musical processing and abilities include congenital amusia, tone deafness, musical hallucinations, musical anhedonia, acquired music agnosia, and arrhythmia (beat deafness).

Professions requiring essential musical skills include vocalist, instrumentalist, lyricist, dancer, sound engineer and composer. Musical intelligence is combined with kinesthetic to produce instrumentalists, dancers and, combined with a linguistic intelligence, for music critics and lyricists. Music combined with interpersonal intelligence is required for success as a music therapist or teacher.

Visual-spatial

[edit]This area deals with spatial awareness / judgment and the ability to visualize with the mind's eye.[17] It is composed of two main dimensions: A) mental visualization and B) perception of the physical world (spatial arrangements and objects). It includes both practical problem-solving as well as artistic creations. Spatial ability is one of the three factors beneath g (general intelligence) in the hierarchical model of intelligence.[19] Many I.Q. tests include a measure of spatial problem-solving skills, e.g., block design and mental rotation of objects.[20]

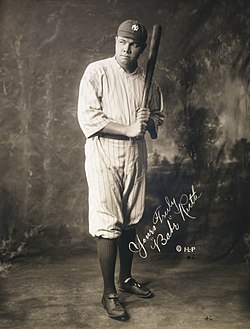

Visual-spatial intelligence can be expressed in both practical (e.g., drafting and building) or artistic (e.g., fine art, crafts, floral arrangements) ways. Or they can be combined in fields such as architecture, industrial design, landscape design, and fashion design. Visual-spatial processing is often combined with the kinesthetic intelligence and referred to as eye-hand or visual-motor integration for tasks such as hitting a baseball (see Babe Ruth example for Kinesthetic), sewing, golf or skiing.

Professions that emphasize skill with visual-spatial processing include carpentry, engineering, designers, pilots, firefighters, surgeons, commercial and fine arts and crafts. Spatial intelligence combined with linguistic is required for success as an art critic or textbook graphic designer. Spatial artistic skills combined with naturalist sensitivity produce a pet groomer or clothing designer, costumer.

Linguistic

[edit]The core linguistic ability is sensitivity to words and their meanings. People with high verbal-linguistic intelligence display a facility with expressive language and verbal comprehension. They are typically good at reading, writing, telling stories, rhetoric and memorizing words along with dates.[17] Verbal ability is one of the most g-loaded abilities.[21] Linguistic (academic aspect) intelligence is measured with the Verbal Intelligence Quotient (IQ) in Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV).

Deficits in linguistic abilities include expressive and receptive aphasia, agraphia, specific language impairment, written language disorder and word recognition deficit (dyslexia).

Linguistic ability can be expressed according to Triarchic theory in three main ways: analytical-academic (reading, writing, definitions); practical (verbal or written directions, explanations, narration); and creative (story telling, poetry, lyrics, imaginative word play, science fiction).

Professions that require linguistic skills include teaching, sales, management, counselors, leaders, childcare, journalists, academics and politicians (debating and creating support for particular sets of values). Linguistic intelligence combines with all other intelligences to facilitate communication either via the spoken or written word. It is frequently highly correlated with the interpersonal intelligence to facilitate social interactions for education, business and human relations. Successful sports coaches combine three intelligences: kinesthetic, interpersonal and linguistic. Corporate managers require skills in the interpersonal, linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences.

Logical-mathematical

[edit]This area has to do with logic, abstractions, reasoning, calculations, strategic and critical thinking.[17] This intelligence includes the capacity to understand underlying principles of some kind of causal system.[22] Logical reasoning is closely linked to fluid intelligence as well as to general intelligence (g factor).[23] This capacity is most often associated with convergent problem-solving but it also includes divergent thinking associated with “problem-finding”.

This intelligence is most closely associated with the cognitive development theory described by Jean Piaget (1983). The four main types of logical-mathematical intelligence include logical reasoning, calculations, practical thinking (common sense) and discovery.

Deficits in logical-mathematical thinking include acalculia, dyscalculia, mild cognitive impairment, dementia and intellectual disability.

Some critics[who?] believe that the logical and mathematics domains should be separate entities. However, Gardner argues that they both spring from the same source—abstractions taken from real world elements, e.g., logic from words and calculations from the manipulation from objects. This is not dissimilar from the relationship between musical intelligence and vocal or instrumental skills where they are very different expressions springing from a shared musical source.

Professions most closely associated with this intelligence include accounting, bookkeeping, banking, finance, engineering and the sciences. Logic-mathematical skills combine with all the other intelligences to facilitate complex problem solving and creation such as environmental engineering and scientists (naturalist); symphonies (music); public sculptures (visual-spatial) and choreography/ movement analysis (kinesthetic).

Bodily-kinesthetic

[edit]The core elements of the bodily-kinesthetic intelligence are control of one's bodily movements and fine motor control to handle objects skillfully.[17] Gardner elaborates to say that this also includes a sense of timing, a clear sense of the goal of a physical action, along with the ability to train responses. Kinesthetic ability can be displayed in goal-directed activities (athletics, handcrafts, etc.) as well as in more expressive movements (drama, dance, mime and gestures). Expressive movements can be for either concepts or feelings. For example, saluting, shaking hands or facial expressions can convey both ideas and emotions. Two major kinesthetic categories are gross and fine motor skills.

Deficits in kinesthetic ability are described as proprioception disorders affecting body awareness, coordination, balance, dexterity and motor control.

Gardner believes that careers that suit those with high bodily-kinesthetic intelligence include: athletes, dancers, musicians, actors, craftspeople, builders, technicians, and firefighters. Although these careers can be duplicated through virtual simulation, they will not produce the actual physical learning that is needed in this intelligence.[24]

Often people with high physical intelligence combined with visual motion acuity will have excellent hand-eye coordination and be very agile; they are precise and accurate in movement (surgeons) and can express themselves using their body (actors and dancers). Gardner referred to the idea of natural skill and innate kinesthetic intelligence within his discussion of the autobiographical story of Babe Ruth – a legendary baseball player who, at 15, felt that he had been 'born' on the pitcher's mound. Seeing the pitched ball and coordinating one’s swing to meet it over the plate requires highly developed visual-motor integration. Each sport requires its own distinctive combination of specific skills associated with the kinesthetic and visual-spatial intelligences.

Physical ability

[edit]Physical intelligence, also known as bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, is any intelligence derived through physical and practiced learning such as sports, dance, or craftsmanship. It may refer to the ability to use one's hands to create, to express oneself with one's body, a reliance on tactile mechanisms and movement, and accuracy in controlling body movement. An individual with high physical intelligence is someone who is adept at using their physical body to solve problems and express ideas and emotions.[25] The ability to control the physical body and the mind-body connection is part of a much broader range of human potential as set out in Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences.[26]

Characteristics

[edit]Exhibiting well developed bodily kinesthetic intelligence will be reflected in a person's movements and how they use their physical body. Often people with high physical intelligence will have excellent hand-eye coordination and be very agile; they are precise and accurate in movement and can express themselves using their body. Gardner referred to the idea of natural skill and innate physical intelligence within his discussion of the autobiographical story of Babe Ruth – a legendary baseball player who, at 15, felt that he has been 'born' on the pitcher's mound. Individuals with a high body-kinesthetic, or physical intelligence, are likely to be successful in physical careers, including athletes, dancers, musicians, police officers, and soldiers.

Interpersonal

[edit]In MI theory, individuals who have high interpersonal intelligence are characterized by their sensitivity to others' moods, feelings, temperaments, motivations, and their ability to cooperate or to lead a group. According to Thomas Armstrong in How Are Kids Smart: Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom, "Interpersonal intelligence is often misunderstood with being extroverted or liking other people.[27] Those with high interpersonal intelligence communicate effectively and empathize easily with others, and may be either leaders or followers. They often enjoy discussion and debate." They have insightful understanding of other peoples' point of view. Daniel Goleman based his concept of emotional intelligence in part on the feeling aspects of the intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences.[28] Interpersonal skill can be displayed in either one-on-one and group interactions.

Deficits in interpersonal understanding are described as ego centrism[citation needed], narcissism[citation needed], socio-pathology[citation needed], Asperger’s Syndrome[citation needed] and autism[citation needed].

Gardner believes that careers that suit those with high interpersonal intelligence include leaders, politicians, managers, teachers, clergy, counselors, social workers and sales persons.[29][30] Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King and Lyndon Johnson are cited as historical leaders with exceptional interpersonal intelligence. Interpersonal combined with intrapersonal management are required for successful leaders, psychologists, life coaches and conflict negotiators. And obviously, team sports require specific combinations of the interpersonal and kinesthetic intelligences while individual sports emphasize the kinesthetic and intrapersonal intelligences (i.e., Tiger Woods and gymnasts).

In theory, individuals who have high interpersonal intelligence are characterized by their sensitivity to others' moods, feelings, temperaments, motivations, and their ability to cooperate to work as part of a group. According to Gardner in How Are Kids Smart: Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom, "Inter- and Intra- personal intelligence is often misunderstood with being extroverted or liking other people".[31] "Those with high interpersonal intelligence communicate effectively and empathize easily with others, and may be either leaders or followers. They often enjoy discussion and debate." Gardner has equated this with emotional intelligence of Goleman.

Intrapersonal

[edit]This refers to having a deep and accurate understanding of the self; what one's strengths and weaknesses are, what makes one unique, being able to predict and manage one's own reactions, emotions and behaviors. Activities associated with this intelligence include introspection and self-reflection. Intrapersonal skills can be categorized in at least four areas: metacognition, awareness of thoughts, management of feelings and emotions, behavior, self-management, decision-making and judgment.

Deficits in intrapersonal understanding are described as anosognosia, depersonalization, dissociation and self-dysregulation (ADHD).

Leaders and people in high stress occupations need well developed intrapersonal skills, e.g., pilots, police and firefighters, entrepreneurs, middle managers, first responders and health care providers. Mahatma Gandhi, Jesus and Martin Luther King Jr. are all noted for their strong self-awareness. Deficits in intrapersonal understanding may be correlated with ADHD, substance abuse and emotional disturbances (mid-life crisis, etc.).

Intrapersonal intelligence may be correlated with concepts such as self-confidence, introspection and self-efficacy but it should not be confused with personality styles/preferences such as narcissism, self-esteem, introversion or shyness. High level performance in many demanding professions and roles requires exceptional intrapersonal intelligence: Olympic athletes, professional golfers, stage performers, CEOs, crisis managers.

Naturalistic

[edit]Not part of Gardner's original seven, naturalistic intelligence was proposed by him in 1995. "If I were to rewrite Frames of Mind today, I would probably add an eighth intelligence – the intelligence of the naturalist. It seems to me that the individual who is readily able to recognize flora and fauna, to make other consequential distinctions in the natural world, and to use this ability productively (in hunting, in farming, in biological science) is exercising an important intelligence and one that is not adequately encompassed in the current list."[32] This area has to do with nurturing and relating information to one's natural surroundings.[17] Examples include classifying natural forms such as animal and plant species and rocks and mountain types. Essential cognitive skills include pattern recognition, taxonomy and empathy for living beings. Nature deficit disorder describes a recent hypothesis that mental health is negatively impacted by a lack of attention to and understanding of nature, e.g., nature deficit disorder.

This sort of ecological receptiveness is deeply rooted in a "sensitive, ethical, and holistic understanding" of the world and its complexities – including the role of humanity within the greater ecosphere.[33]

This ability continues to be central in such roles like veterinarians, ecological scientists and botanists.

Proposed additional intelligences

[edit]From the beginning Howard Gardner has stated that there may be more intelligences beyond the original seven identified in 1983. That is why the naturalist was added to the list in 1999. Several other human capacities were rejected because they do not meet enough of the criteria including personality characteristics such as humor, sexuality and extroversion.

Pedagogical and digital

[edit]In January 2016, Gardner mentioned in an interview with Big Think that he was considering adding the teaching–pedagogical intelligence "which allows us to be able to teach successfully to other people".[34] In the same interview, he explicitly refused some other suggested intelligences like humour, cooking and sexual intelligence.[34] Professor Nan B. Adams argues that based on Gardner's definition of multiple intelligences, digital intelligence – a meta-intelligence composed of many other identified intelligences and stemmed from human interactions with digital computers – now exists.[35]

Use in education

[edit]Within his Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Gardner stated that our "educational system is heavily biased towards linguistic modes of intersection and assessment and, to a somewhat lesser degree, toward logical quantities modes as well". His work went on to shape educational pedagogy and influence relevant policy and legislation across the world; with particular reference to how teachers must assess students' progress to establish the most effective teaching methods for the individual learner. Gardner's research into the field of learning regarding bodily kinesthetic intelligence has resulted in the use of activities that require physical movement and exertion, with students exhibiting a high level of physical intelligence reporting to benefit from 'learning through movement' in the classroom environment.[36]

Although the distinction between intelligences has been set out in great detail, Gardner opposes the idea of labelling learners to a specific intelligence. Gardner maintains that his theory should "empower learners", not restrict them to one modality of learning.[37] According to Gardner, an intelligence is "a biopsychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture".[38] According to a 2006 study, each of the domains proposed by Gardner involves a blend of the general g factor, cognitive abilities other than g, and, in some cases, non-cognitive abilities or personality characteristics.[39]

Gardner defines an intelligence as "bio-psychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture".[40] According to Gardner, there are more ways to do this than just through logical and linguistic intelligence. Gardner believes that the purpose of schooling "should be to develop intelligences and to help people reach vocational and avocational goals that are appropriate to their particular spectrum of intelligences. People who are helped to do so, [he] believe[s], feel more engaged and competent and therefore more inclined to serve society in a constructive way."[a]

Gardner contends that Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests focus mostly on logical and linguistic intelligence. Upon doing well on these tests, the chances of attending a prestigious college or university increase, which in turn creates contributing members of society.[41] While many students function well in this environment, there are those who do not. Gardner's theory argues that students will be better served by a broader vision of education, wherein teachers use different methodologies, exercises and activities to reach all students, not just those who excel at linguistic and logical intelligence. It challenges educators to find "ways that will work for this student learning this topic".[42]

James Traub's article in The New Republic notes that Gardner's system has not been accepted by most academics in intelligence or teaching.[43] Gardner states that "while Multiple Intelligences theory is consistent with much empirical evidence, it has not been subjected to strong experimental tests ... Within the area of education, the applications of the theory are currently being examined in many projects. Our hunches will have to be revised many times in light of actual classroom experience."[44]

Jerome Bruner agreed with Gardner that the intelligences were "useful fictions", and went on to state that "his approach is so far beyond the data-crunching of mental testers that it deserves to be cheered."[45]

George Miller, a prominent cognitive psychologist, wrote in The New York Times Book Review that Gardner's argument consisted of "hunch and opinion" and Charles Murray and Richard J. Herrnstein in The Bell Curve (1994) called Gardner's theory "uniquely devoid of psychometric or other quantitative evidence".[46]

Distinction to learning styles

[edit]The notion of learning styles is problematic, and their educational use is suspect.[47] Gardner has regularly explained the distinction between Theory of multiple intelligences and various learning style models. A big problem is that there are more than 80 different learning styles models so it is difficult to know which model is being referred to when making a comparison or planning instruction.[48] A key difference is that learning styles typically refer to sensory modalities, preferences, personality characteristics, attitudes, and interests while the multiple intelligences are cognitive abilities with defined levels of skill. It is easy to see why they are confused given the popularity of VAK (Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic) and Introversion, Extroversion models. Their names sound alike and they share sensory systems (vision, hearing, physicality) but the eight intelligences are much more than the senses or personal preferences.

While learning style theories are fundamentally different from the eight intelligences, there is a model proposed by Richard Strong and others that integrates a person’s preference with the eight intelligences to produce a descriptive tapestry of a person’s intellectual dispositions.[49] The four styles are Mastery, Understanding, Interpersonal, and Self-Expressive. For the visual-spatial intelligence expressed artistically, a person may have a distinct pattern of preferences for realistic imagery (Mastery), conceptual art (Understanding), portraiture (Interpersonal) or abstract expression (Self-Expressive). This model has not been tested empirically.

Talents and aptitudes

[edit]Intelligences not typically associated with academic achievement have been traditionally delegated to the status of talents or aptitudes—e.g., musical, visual-spatial, kinesthetic and naturalist. Gardner takes issue with this hierarchy because it lowers the importance of these “non-academic” intelligences and devalues their contribution to human thought, individual development and culture. Gardner is fine with calling them all talents (or aptitudes) (including logical-mathematical and linguistic) so long as they are seen to be of equal value.[1]

In spite of its lack of general acceptance in the psychological community, Gardner's theory has been adopted by many schools, where it is often conflated with learning styles,[50] and hundreds of books have been written about its applications in education.[51] Some of the applications of Gardner's theory have been described as "simplistic" and Gardner himself has said he is "uneasy" with the way his theory has been used in schools.[52] Gardner has denied that multiple intelligences are learning styles and agrees that the idea of learning styles is incoherent and lacking in empirical evidence.[53] Gardner summarizes his approach with three recommendations for educators: individualize the teaching style (to suit the most effective method for each student), pluralize the teaching (teach important materials in multiple ways), and avoid the term "styles" as being confusing.[53]

Criticism

[edit]Gardner argues that there is a wide range of cognitive abilities, but that there are only very weak correlations among them. For example, the theory postulates that a child who learns to multiply easily is not necessarily more intelligent than a child who has more difficulty on this task. The child who takes more time to master multiplication may best learn to multiply through a different approach, may excel in a field outside mathematics, or may be looking at and understanding the multiplication process at a fundamentally deeper level.

Intelligence tests and psychometrics have generally found high correlations between different aspects of intelligence, rather than the low correlations which Gardner's theory predicts, supporting the prevailing theory of general intelligence rather than multiple intelligences (MI).[54] The theory has been criticized by mainstream psychology for its lack of empirical evidence, and its dependence on subjective judgement.[55]

Definition of intelligence

[edit]A major criticism of the theory is that it is ad hoc: that Gardner is not expanding the definition of the word "intelligence", but rather denies the existence of intelligence as traditionally understood, and instead uses the word "intelligence" where other people have traditionally used words like "ability" and "aptitude". This practice has been criticized by Robert J. Sternberg,[56][57] Michael Eysenck,[58] and Sandra Scarr.[59] White (2006) points out that Gardner's selection and application of criteria for his "intelligences" is subjective and arbitrary, and that a different researcher would likely have come up with different criteria.[60]

Defenders of MI theory argue that the traditional definition of intelligence is too narrow, and thus a broader definition more accurately reflects the differing ways in which humans think and learn.[61]

Some criticisms arise from the fact that Gardner has not provided a test of his multiple intelligences. He originally defined it as the ability to solve problems that have value in at least one culture, or as something that a student is interested in. He then added a disclaimer that he has no fixed definition, and his classification is more of an artistic judgment than fact:

Ultimately, it would certainly be desirable to have an algorithm for the selection of intelligence, such that any trained researcher could determine whether a candidate's intelligence met the appropriate criteria. At present, however, it must be admitted that the selection (or rejection) of a candidate's intelligence is reminiscent more of an artistic judgment than of a scientific assessment.[1]

Generally, linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities are called intelligence, but artistic, musical, athletic, etc. abilities are not. Gardner argues this causes the former to be needlessly aggrandized. Certain critics are wary of this widening of the definition, saying that it ignores "the connotation of intelligence ... [which] has always connoted the kind of thinking skills that makes one successful in school."[62]

Gardner writes "I balk at the unwarranted assumption that certain human abilities can be arbitrarily singled out as intelligence while others cannot."[63] Critics hold that given this statement, any interest or ability can be redefined as "intelligence". Thus, studying intelligence becomes difficult, because it diffuses into the broader concept of ability or talent. Gardner's addition of the naturalistic intelligence and conceptions of the existential and moral intelligence are seen as the fruits of this diffusion. Defenders of the MI theory would argue that this is simply a recognition of the broad scope of inherent mental abilities and that such an exhaustive scope by nature defies a one-dimensional classification such as an IQ value.

The theory and definitions have been critiqued by Perry D. Klein as being so unclear as to be tautologous and thus unfalsifiable. Having a high musical ability means being good at music while at the same time being good at music is explained by having high musical ability.[64]

Henri Wallon argues that "We can not distinguish intelligence from its operations".[65] Yves Richez distinguishes 10 Natural Operating Modes (Modes Opératoires Naturels – MoON).[66] Richez's studies are premised on a gap between Chinese thought and Western thought. In China, the notion of "being" (self) and the notion of "intelligence" do not exist.[clarification needed] These are claimed to be Graeco-Roman inventions derived from Plato. Instead of intelligence, Chinese refers to "operating modes", which is why Yves Richez does not speak of "intelligence" but of "natural operating modes" (MoON).

Validity

[edit]Critics argue that MI cannot be taken seriously as a scientific theory of intelligence for a number of reasons, the most common are given below:

- It is not scientific as in a body of knowledge acquired by performing replicated experiments in the laboratory.[67]

- There is conceptual confusion for determining exactly what intelligence is and what it isn’t, e.g., MI conflates personality, talent and learning styles with intelligence. MI does not value reasoning and academic skills.[25]

- There are no empirical, experimental studies using psychometrics to establish validity. The proposed intelligences are not proven to be sufficiently independent to warrant separate identification.[68][69][70][71]

- There is no evidence for educational efficacy and its use may undermine school effectiveness.[citation needed]

Neo-Piagetian criticism

[edit]Andreas Demetriou suggests that theories which overemphasize the autonomy of the domains are as simplistic as the theories that overemphasize the role of general intelligence and ignore the domains. He agrees with Gardner that there are indeed domains of intelligence that are relevantly autonomous of each other.[72] Some of the domains, such as verbal, spatial, mathematical, and social intelligence are identified by most lines of research in psychology. In Demetriou's theory, one of the neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development, Gardner is criticized for underestimating the effects exerted on the various domains of intelligences by the various subprocesses that define overall processing efficiency, such as speed of processing, executive functions, working memory, and meta-cognitive processes underlying self-awareness and self-regulation. All of these processes are integral components of general intelligence that regulate the functioning and development of different domains of intelligence.[73]

The domains are to a large extent expressions of the condition of the general processes, and may vary because of their constitutional differences but also differences in individual preferences and inclinations. Their functioning both channels and influences the operation of the general processes.[74][75] Thus, one cannot satisfactorily specify the intelligence of an individual or design effective intervention programs unless both the general processes and the domains of interest are evaluated.[76][77]

Human adaptation to multiple environments

[edit]The premise of the multiple intelligences hypothesis, that human intelligence is a collection of specialist abilities, have been criticized for not being able to explain human adaptation to most if not all environments in the world. In this context, humans are contrasted to social insects that indeed have a distributed "intelligence" of specialists, and such insects may spread to climates resembling that of their origin but the same species never adapt to a wide range of climates from tropical to temperate by building different types of nests and learning what is edible and what is poisonous. While some such as the leafcutter ant grow fungi on leaves, they do not cultivate different species in different environments with different farming techniques as human agriculture does. It is therefore argued that human adaptability stems from a general ability to falsify hypotheses and make more generally accurate predictions and adapt behavior thereafter, and not a set of specialized abilities which would only work under specific environmental conditions.[78][79]

IQ tests

[edit]Gardner argues that IQ tests only measure linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities. He argues the importance of assessing in an "intelligence-fair" manner. While traditional paper-and-pen examinations favor linguistic and logical skills, there is a need for intelligence-fair measures that value the distinct modalities of thinking and learning that uniquely define each intelligence.[17]

Psychologist Alan S. Kaufman points out that IQ tests have measured spatial abilities for 70 years.[80] Modern IQ tests are greatly influenced by the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory which incorporates a general intelligence but also many more narrow abilities. While IQ tests do give an overall IQ score, they now also give scores for many more narrow abilities.[80]

Lack of empirical evidence

[edit]Many of Gardner's "intelligences" correlate with the g factor, supporting the idea of a single dominant type of intelligence. Each of the domains proposed by Gardner involved a blend of g, of cognitive abilities other than g, and, in some cases, of non-cognitive abilities or of personality characteristics.[39]

The Johnson O'Connor Research Foundation has tested hundreds of thousands of people[81] to determine their "aptitudes" ("intelligences"), such as manual dexterity, musical ability, spatial visualization, and memory for numbers.[82] There is correlation of these aptitudes with the g factor, but not all are strongly correlated; correlation between the g factor and "inductive speed" ("quickness in seeing relationships among separate facts, ideas, or observations") is only 0.5,[83] considered a moderate correlation.[84]

A critical review of MI theory argues that there is little empirical evidence to support it:

To date, there have been no published studies that offer evidence of the validity of the multiple intelligences. In 1994 Sternberg reported finding no empirical studies. In 2000 Allix reported finding no empirical validating studies, and at that time Gardner and Connell conceded that there was "little hard evidence for MI theory" (2000, p. 292).[citation needed] In 2004 Sternberg and Grigerenko stated that there were no validating studies for multiple intelligences, and in 2004 Gardner asserted that he would be "delighted were such evidence to accrue",[85] and admitted that "MI theory has few enthusiasts among psychometricians or others of a traditional psychological background" because they require "psychometric or experimental evidence that allows one to prove the existence of the several intelligences".[85][86]

The same review presents evidence to demonstrate that cognitive neuroscience research does not support the theory of multiple intelligences:

... the human brain is unlikely to function via Gardner's multiple intelligences. Taken together the evidence for the intercorrelations of subskills of IQ measures, the evidence for a shared set of genes associated with mathematics, reading, and g, and the evidence for shared and overlapping "what is it?" and "where is it?" neural processing pathways, and shared neural pathways for language, music, motor skills, and emotions suggest that it is unlikely that each of Gardner's intelligences could operate "via a different set of neural mechanisms" (1999, p. 99). Equally important, the evidence for the "what is it?" and "where is it?" processing pathways, for Kahneman's two decision-making systems, and for adapted cognition modules suggests that these cognitive brain specializations have evolved to address very specific problems in our environment. Because Gardner claimed that the intelligences are innate potentialities related to a general content area, MI theory lacks a rationale for the phylogenetic emergence of the intelligences.[86]

However, more recent research from Branton Shearer in 2017 was able to identify both structures that activate in common, as well as separately, across Gardner's 8 intelligences.[87]

See also

[edit]- Charles Spearman – English psychologist (1863–1945)

Notes

[edit]- ^ This information is based on an informal talk given on the 350th anniversary of Harvard University on 5 September 1986. Harvard Education Review, Harvard Education Publishing Group, 1987, 57, 187–193.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Gardner 1983.

- ^ Armstrong, Thomas (2009). Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom. ASCD. ISBN 978-1416607892.

- ^ Sousa, David A. (2011). How the Brain Learns. Corwin. ISBN 978-1412997973.

- ^ Gottfredson, Linda S. (1997). Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns. American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.2.131 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Deary, Ian J. (2020). Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198796206.

- ^ Gardner 1999.

- ^ Robert J., Sternberg. The general factor of intelligence: How general is it?. American Psychological Association. pp. 331–380.

- ^ "Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives – The Center for Teaching and Learning". Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ Noble, T. (2004). Integrating the revised Bloom's taxonomy with multiple intelligences: A planning tool for curriculum differentiation. Teachers College Record. pp. 193–211.

- ^ "The Essential Howard Gardner on Education 9780807769829 | Teachers College Press". www.tcpress.com. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ Harris, Michael H. (1996). "Review of The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 66 (1): 89–92. doi:10.1086/602846. ISSN 0024-2519. JSTOR 4309091.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (2011). Multiple intelligences: The first thirty years. Introduction to Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences (3rd ed.).

- ^ Slavin, Robert. Educational Psychology (2009) p. 117, ISBN 0-205-59200-7

- ^ Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wu, Wu-Tien (2004). "Multiple Intelligences, Educational Reform, and a Successful Career". Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education. 106 (1): 181–192. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00327.x. ISSN 0161-4681.

- ^ "Multiple Intelligences Go to School: Educational Implications of the Theory of Multiple Intelligences" (PDF). www.sfu.ca. 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gardner, H.; Hatch, T. (1989). "Multiple intelligences go to school: Educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences" (PDF). Educational Researcher. 18 (8): 4. doi:10.3102/0013189X018008004. S2CID 145224128. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Brown, Rachel M.; Zatorre, Robert J.; Penhune, Virginia B. (2015). "Expert music performance: cognitive, neural, and developmental bases". Music, Neurology, and Neuroscience: Evolution, the Musical Brain, Medical Conditions, and Therapies. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 217. pp. 57–86. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.021. ISBN 978-0-444-63551-8. ISSN 1875-7855. PMID 25725910.

- ^ Altus, William D. (1959). "Book Reviews : The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence, by David Wechsler. Fourth Edition. Baltimore: William & Wilkins, 1958. Pp. viii + 297". Educational and Psychological Measurement. 19 (1): 120–122. doi:10.1177/001316445901900115. ISSN 0013-1644.

- ^ Newcombe, Nora (1 January 2010). "Early Education for Spatial Intelligence: Why, What, and How". Mind, Brain, and Education. 4 (3): 102–111. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2010.01089.x.

- ^ Wechsler, D. (1997). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III.

- ^ "Howard Gardner's Multiple Intelligence Theory". PBS. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-analytic Studies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521382755.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (1984). "Heteroglossia: A Global Perspective". Interdisciplinary Journal of Theory of Postpedagogical Studies.

- ^ a b OpenLibrary.org. "Fifty Modern Thinkers on Education | Open Library". Open Library. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Gardner, Howard; Hatch, Thomas (1989). "Educational Implications of the Theory of Multiple Intelligences". Educational Researcher. 18 (8): 4–10. doi:10.3102/0013189x018008004. ISSN 0013-189X. S2CID 145224128.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (1995). How Are Kids Smart: Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom. ISBN 1-887943-03-X.

- ^ Gardner, H. (2015). Bridging the Gaps: A Portal for Curious MindsPro Unlimited. (at 17 minutes). soundcloud.com

- ^ Gardner, Howard (2002). "Interpersonal Communication amongst Multiple Subjects: A Study in Redundancy". Experimental Psychology.

- ^ Gardner, Howard (2002). "Interpersonal Communication amongst Multiple Subjects: A Study in Redundancy". Experimental Psychology.

- ^ Gardner, H. (1995). How Are Kids Smart: Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom—Administrators' Version. ISBN 1-887943-03-X.

- ^ Gardner, H. (1995). "Reflections on multiple intelligences: Myths and messages" (PDF). Phi Delta Kappan. 77: 200–209. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Morris, M. (2004). "Ch. 8. The Eight One: Naturalistic Intelligence". In Kincheloe, Joe L. (ed.). Multiple Intelligences Reconsidered. Peter Lang. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-8204-7098-6.

- ^ a b Gardner, Howard. (2016). Intelligence Isn't black and white: There are 8 different kinds. Bigthing. come. video. Check minutes 5:00–5:55 and 8:16

- ^ Adams, Nan B. (2004). "Digital Intelligence Fostered by Technology". Journal of Technology Studies. 30 (2): 93–97. doi:10.21061/jots.v30i2.a.5 – via ERIC.

- ^ White, John Ponsford. (1998). Do Howard Gardner's Multiple Intelligences Add Up?. University of London; Institute of Education. London: Institute of Education, University of London. ISBN 0-85473-552-6. OCLC 39659187.

- ^ McKenzie, W. (2005). Multiple intelligences and instructional technology. ISTE (International Society for Technology Education). ISBN 156484188X

- ^ Gardner 1999, p. 33-4

- ^ a b Visser, Beth A.; Ashton, Michael C.; Vernon, Philip A. (2006). "g and the measurement of Multiple Intelligences: A response to Gardner" (PDF). Intelligence. 34 (5): 507–510. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.04.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011.

- ^ Gardner 1999, pp. 33–34

- ^ Gardner 1993, p. 6

- ^ Gardner 1999, p. 154

- ^ Traub, James (1998). "Multiple intelligence disorder". The New Republic. Vol. 219, no. 17. p. 20.

- ^ Gardner 1993, p. 33

- ^ Bruner, Jerome. "State of the Child". New York Review of Books.

- ^ Eberstadt, Mary (October–November 1999). "The Schools They Deserve" (PDF). Policy Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Philip, Adey; Justin, Dillon (1 October 2012). "Learning styles: unreliable, invalid and impractical and yet still widely used". Bad Education: Debunking Myths In Education. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). pp. 215–230. ISBN 978-0-335-24601-4.

- ^ Sousa, David A.; Tomlinson, Carol A. (2018). Differentiation and the Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-friendly Classroom. Solution Tree. ISBN 978-1-945349-52-2.

- ^ "Integrating Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences". ASCD. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Howard-Jones 2010, p. 23

- ^ Davis et al. 2011, p. 486

- ^ Revell, Phil (31 May 2005). "Each to their own". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b Strauss, Valerie (16 October 2013). "Howard Gardner: 'Multiple intelligences' are not 'learning styles'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Geake, John (2008). "Neuromythologies in education". Educational Research. 50 (2): 123–133. doi:10.1080/00131880802082518. S2CID 18763506.

- ^ Waterhouse, Lynn (2006). "Multiple Intelligences, the Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review" (PDF). Educational Psychologist. 41 (4): 207–225. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4104_1. S2CID 33806452. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ Sternberg, R. J. (Winter 1983). "How much Gall is too much gall? Review of Frames of Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences". Contemporary Education Review. 2 (3): 215–224.

- ^ Sternberg, R. J. (1991). "Death, taxes, and bad intelligence tests". Intelligence. 15 (3): 257–270. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(91)90035-C.

- ^ Eysenck 1994

- ^ Scarr, S. (1985). "An authors frame of mind [Review of Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences]". New Ideas in Psychology. 3 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1016/0732-118X(85)90056-X.

- ^ Davis et al. 2011, p. 489

- ^ Nikolova, K.; Taneva-Shopova, S. (2007), Multiple intelligences theory and educational practice, vol. 26, Annual Assesn Zlatarov University, pp. 105–109

- ^ Willingham, Daniel T. (2004). "Check the Facts: Reframing the Mind". Education Next: 19–24. PDF copy

- ^ Gardner, Howard (1998). "A Reply to Perry D. Klein's 'Multiplying the problems of intelligence by eight'". Canadian Journal of Education. 23 (1): 96–102. doi:10.2307/1585968. JSTOR 1585790.

- ^ Klein, Perry D. (1998). "A Response to Howard Gardner: Falsifiability, Empirical Evidence, and Pedagogical Usefulness in Educational Psychologies". Canadian Journal of Education. 23 (1): 103–112. doi:10.2307/1585969. JSTOR 1585969.

- ^ According to formulation of Émile Jalley for Henri Wallon in Principes de psychologie appliquée (Œuvre 1, édition L'Harmattan, 2015) : « On ne saurait distinguer l'intelligence de ses opérations »

- ^ Richez, Yves (2018). Corporate talent detection and development. Wiley Publishing.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert J. (September 2012). "Intelligence". WIREs Cognitive Science. 3 (5): 501–511. doi:10.1002/wcs.1193. ISSN 1939-5078. PMID 26302705.

- ^ van der Ploeg, P. (2016). "Multiple Intelligences and pseudo-science."

- ^ Waterhouse, L. (2006a). "Multiple intelligences, the Mozart effect, and emotional intelligence: A critical review." Educational Psychologist, 41, 207–225.

- ^ Waterhouse, Lynn (Fall 2006b), "Inadequate Evidence for Multiple Intelligences, Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence Theories", Educational Psychologist, 41 (4): 247–255, doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4104_5, S2CID 26668858

- ^ Jensen, A. R. (2008). "Review of “Howard Gardner under fire: The rebel psychologist faces his critics.”" Intelligence, 36(1).

- ^ Demetriou, A.; Spanoudis, G.; Mouyi, A. (2011). "Educating the Developing Mind: Towards an Overarching Paradigm". Educational Psychology Review. 23 (4): 601–663. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9178-3.

- ^ Demetriou & Raftopoulos 2005, p. 68

- ^ Demetriou, A.; Efklides, A.; Platsidou, M.; Campbell, Robert L. (1993). "The architecture and dynamics of developing mind: Experiential structuralism as a frame for unifying cognitive developmental theories". Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 58 (234): 1–205. doi:10.2307/1166053. JSTOR 1166053. PMID 8232367.

- ^

Demetriou, A., Christou, C.; Spanoudis, G.; Platsidou, M. (2002). "The development of mental processing: Efficiency, working memory, and thinking". Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 67 (268): i–viii, 1–155, discussion 156. doi:10.1111/1540-5834.671174. PMID 12360826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Demetriou, A.; Kazi, S. (2006). "Self-awareness in g (with processing efficiency and reasoning". Intelligence. 34 (3): 297–317. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.10.002.

- ^ Demetriou, Mouyi & Spanoudis 2010

- ^ Steven Mithen 2005 edition|"Creativity in Human Evolution and Prehistory"

- ^ Rolf W. Frohlich 2009 edition|"Evolutionary Intelligence: The Anatomy of Human Survival"

- ^ a b Kaufman 2009

- ^ "About Us". Johnson O'Connor Research Foundation. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Aptitude Testing and Research since 1922". Johnson O'Connor Research Foundation. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Haier, Richard (29 May 2014). "Gray Matter and Intelligence Factors: Is There a Neuro-g?". p. 4. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "The Correlation Coefficient: Definition". DM-Stat 1 Consulting. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ a b Gardner 2004, p. 214

- ^ a b Waterhouse, Lynn (Fall 2006a). "Multiple Intelligences, the Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence: A critical review". Educational Psychologist. 41 (4): 207–225. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4104_1. S2CID 33806452.

- ^ Shearer, Branton; Karanian, J. M. (2017). "The neuroscience of intelligence: Empirical support for the theory of multiple intelligences?". Trends in Neuroscience and Education. 6: 211–223. doi:10.1016/j.tine.2017.02.002.

Works cited

[edit]- Davis, Katie; Christodoulou, Joanna; Seider, Scott; Gardner, Howard (2011), "The Theory of Multiple Intelligences", in Sternberg, Robert J.; Kaufman, Barry (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, Cambridge University Press, pp. 485–503, ISBN 978-0521518062

- Demetriou, Andreas; Raftopoulos, Athanassios (2005), Cognitive Developmental Change: Theories, Models and Measurement, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521825795

- Demetriou, A.; Mouyi, A.; Spanoudis, G. (2010), "The development of mental processing", in Overton, W. F. (ed.), The Handbook of Life-Span Development: Cognition, Biology and Methods, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 36–55, ISBN 978-0-470-39011-5

- Eysenck, M. W., ed. (1994), The Blackwell Dictionary of Cognitive Psychology, Blackwell Publishers, pp. 192–193, ISBN 978-0631192572

- Gardner, Howard (1983), Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0133306149

- Gardner, Howard (1993), Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0465018222

- Gardner, Howard (1999), Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-02611-1

- Gardner, H. (2004), Changing Minds: The art and science of changing our own and other people's minds, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN 978-1422103296

- Howard-Jones, Paul (2010), Introducing Neuroeducational Research, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415472005

- Kaufman, Alan S. (2009), IQ Testing 101, Springer Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8261-0629-2

Further reading

[edit]- Gardner, Howard (2006), Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0465047680

- Kavale, Kenneth A.; Forness, Steven R. (1987), "Substance over style: Assessing the efficacy of modality testing and teaching", Exceptional Children, 54 (3): 228–39, doi:10.1177/001440298705400305, S2CID 143375102

- Klein, Perry, D. (1997), "Multiplying the problems of intelligence by eight: A critique of Gardner's theory", Canadian Journal of Education, 22 (4): 377–94, doi:10.2307/1585790, JSTOR 1585790, S2CID 6560781

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lohman, D. F. (2001), "Fluid intelligence, inductive reasoning, and working memory: Where the theory of Multiple Intelligences falls short" (PDF), in Colangelo, N.; Assouline, S. (eds.), Talent Development IV: Proceedings from the 1998 Henry B. & Jocelyn Wallace National Research Symposium on talent development, Great Potential Press, pp. 219–228, ISBN 978-0-910707-39-8, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022

- Kincheloe, Joe L.; Nolan, Kathleen; Progler, Yusef; Appelbaum, Peter; Cary, Richard; Blumenthal-Jones, Donald S.; Morris, Marla; Lemke, Jay L.; Cannella, Gaile S.; Weil, Danny; Berry, Kathleen S. (2004), Kincheloe, Joe L. (ed.), Multiple Intelligences Reconsidered, Counterpoints v. 278, Peter Lang, ISBN 978-0-8204-7098-6

- Sew, Jyh Wee, "Joe L. Kincheloe (ed.) Multiple Intelligences Reconsidered" (PDF), California State University, Fullerton, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022

- Sternberg, R. J. (1988), The Triarchic Mind: A New Theory of Human Intelligence, Penguin Books

- Vîrtop, Sorin-Avram (2014), "From Theory to Practice: The Multiple Intelligences Theory Experience in a Romanian Secondary School", Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116: 5020–4, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1066

- Vîrtop, Sorin-Avram (2015), "Possibilities of Instruction Based on the Students' Potential and Multiple Intelligences Theory", Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191: 1772–6, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.223

External links

[edit]- Multiple Intelligences Oasis, Howard Gardner's official website for MI Theory

- Multiple Intelligences, Future Minds and Educating The App Generation: A discussion with Dr Howard Gardner, Bridging the Gaps: A Portal for Curious Minds

Theory of multiple intelligences

View on Grokipedia- Linguistic intelligence: Sensitivity to the meanings, order, and sounds of words, as seen in poets, lawyers, and journalists.[1]

- Logical-mathematical intelligence: Capacity for abstract reasoning, logical deduction, and numerical pattern recognition, evident in scientists and mathematicians.[1]

- Spatial intelligence: Ability to visualize and manipulate mental images of spatial relationships, prominent in architects, pilots, and sculptors.[1]

- Musical intelligence: Skill in perceiving, composing, and appreciating rhythm, pitch, and timbre, demonstrated by composers and musicians.[1]

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence: Proficiency in using one's body to produce or manipulate objects, as in dancers, athletes, and surgeons.[1]

- Interpersonal intelligence: Understanding and interacting effectively with others' emotions, motivations, and intentions, characteristic of leaders and therapists.[1]

- Intrapersonal intelligence: Awareness of one's own emotions, goals, and motivations, supporting self-regulation and personal decision-making.[1]

- Naturalistic intelligence: Recognizing and categorizing elements of the natural environment, such as flora and fauna, often seen in biologists and chefs.[1]