Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Forebrain

View on Wikipedia| Forebrain (Prosencephalon) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D016548 |

| NeuroNames | 27 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1509 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.006 |

| TA2 | 5416 |

| TE | E5.14.1.0.2.0.10 |

| FMA | 61992 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

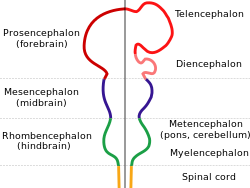

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain controls body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and the display of emotions.

Vesicles of the forebrain (prosencephalon), the midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon) are the three primary brain vesicles during the early development of the nervous system. At the five-vesicle stage, the forebrain separates into the diencephalon (thalamus, hypothalamus, subthalamus, and epithalamus) and the telencephalon which develops into the cerebrum. The cerebrum consists of the cerebral cortex, underlying white matter, and the basal ganglia.

In humans, by 5 weeks in utero it is visible as a single portion toward the front of the fetus. At 8 weeks in utero, the forebrain splits into the left and right cerebral hemispheres.

When the embryonic forebrain fails to divide the brain into two lobes, it results in a condition known as holoprosencephaly. The main structures of the forebrain include the cerebrum, thalamus and hypothalamus.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- NIF Search - Forebrain Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine via the Neuroscience Information Framework