Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Regional policy of the European Union

View on Wikipedia| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The Regional Policy of the European Union (EU), also referred as Cohesion Policy, is a policy with the stated aim of improving the economic well-being of regions in the European Union and also to avoid regional disparities. More than one third of the EU's budget is devoted to this policy, which aims to remove economic, social and territorial disparities across the EU, restructure declining industrial areas and diversify rural areas which have declining agriculture. In doing so, EU regional policy is geared towards making regions more competitive, fostering economic growth and creating new jobs. The policy also has a role to play in wider challenges for the future, including climate change, energy supply and globalisation.

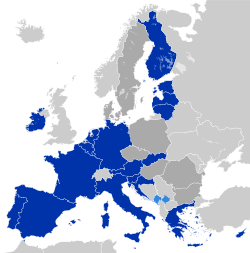

The EU's regional policy covers all European regions, although regions across the EU fall in different categories (so-called objectives), depending mostly on their economic situation. Between 2007 and 2013, EU regional policy consisted of three objectives: Convergence, Regional competitiveness and employment, and European territorial cooperation; the previous three objectives (from 2000 to 2006) were simply known as Objectives 1, 2 and 3.

The policy constitutes the main investment policy of the EU, and is due to account for around of third of its budget, or EUR 392 billion over the period of 2021-2027.[1] In its long-term budget, the EU's Cohesion policy gives particular attention to regions where economic development is below the EU average.[2][3]

Notion of territorial cohesion

[edit]Territorial cohesion is a European Union concept which builds on the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP).[4][5] The main idea of territorial cohesion is to contribute to European sustainable development and competitiveness. It is intended to strengthen the European regions, promote territorial integration and produce coherence of European Union (EU) policies so as to contribute to the sustainable development and global competitiveness of the EU. Sustainable development is defined as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".

The main aim of the territorial cohesion policy is to contribute to a balanced distribution of economic and social resources among the European regions with the priority on the territorial dimension. This means that resources and opportunities should be equally distributed among the regions and their populations. In order to achieve the goal of territorial cohesion, an integrative approach to other EU policies is required.

Objectives

[edit]

Less developed regions

[edit]By far the largest amount of regional policy funding is dedicated to the regions designated as less developed. This covers Europe's poorest regions whose per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is less than 75% of the EU average. This includes nearly all the regions of the new member states, most of Southern Italy, Greece and Portugal, and some parts of the United Kingdom and Spain.

With the addition of the newest member countries in 2004 and 2007, the EU average GDP fell. As a result, some regions in the EU's "old" member states, which used to be eligible for funding under the Convergence objective, became above the 75% threshold. These regions received transitional, "phasing out" support during the previous funding period of 2007–13. Regions that used to be covered under the convergence criteria but got above the 75% threshold even within the EU-15 received "phasing-in" support through the Regional competitiveness and employment objective.[6] [7] Despite the large investment requirements of the EU, cohesion areas continue to have lower investment rates. Only 77% of businesses in transitional regions and 75% of those in less developed regions invested, compared to 79% of businesses in more developed regions.[8]

Financial limitations are more common in less developed areas, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). SMEs in these regions are more than twice as likely (11%) than their counterparts in transition (5%) and non-cohesion zones (5%) to report having financial difficulties.[9][10] Less developed regions also have the lowest percentage of businesses who have made investments to combat climate change or reduce their carbon emissions, at 46%.[8] In 2022, lending from the EIB Group under the SME/mid-cap financing policy reached €3.5 billion.[11][12]

In less developed regions, bank loans account for 49% of finance. Grants make up a larger portion of the financing in less developed areas, accounting for 13% of external financing.[13]

Many regions in Southern Europe and transition regions in higher-income Member States have seen economic downturn and population declines.[14] There has been general growth in GDP per capita and employment, but regional differences within EU nations remain, with considerable discrepancies between capital and non-capital areas, particularly in younger Member States.[15][16]

Women's participation in the workforce, including older women, has grown significantly in recent years, though notable regional differences remain.[17] In cohesion regions, women's employment rates are considerably lower than men's, with gender gaps in employment reaching as high as 30% in parts of Southern Europe.[17][18]

Areas designated as less developed from 2014 to 2020

[edit]- Bulgaria – all (except Southwestern region)

- Croatia - all

- Czech Republic – all (except Prague)

- Estonia – all

- France – French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Réunion

- Greece – Anatoliki Makedonia Thraki, Dytiki Ellada, Ipeiros, Kentriki Makedonia, Thessalia

- Hungary – all (except Central Hungary)

- Italy – Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Apulia, Sicily

- Latvia – all

- Lithuania – all

- Poland – all (except the Warsaw Metro NUTS2 Unit carved out of Masovian Voivodeship)

- Portugal – Alentejo, Azores, Centro, Norte

- Romania – all (except Bucharest)

- Slovakia – all (except Bratislava)

- Slovenia – Vzhodna Slovenija

- Spain – Extremadura

- United Kingdom – Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, West Wales and the Valleys

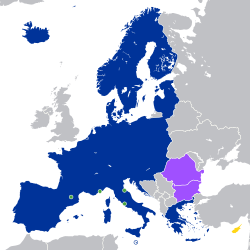

Transition regions

[edit]These are regions whose GDP per capita falls between 75 and 90 percent of the EU average. As such, they receive less funding than the less developed regions but more funding than the more developed regions.

In transition regions, bank loans account for 69% of finance.[19][13] Particularly transitional regions appear to profit from investments in more developed regions. There is a 34% of the impact on GDP and 47% of the impact on employment in some circumstances.[20]

In the green transition, 19% of firms in transition regions claim that climate change is significantly affecting their business, while 43% believe climate change has a minor effect.[21] 25% of businesses in transition regions can also be categorized as "green and digital".

Areas designated as transition regions from 2014 to 2020

[edit]- Austria – Burgenland

- Belgium – all of Wallonia (except Walloon Brabant)

- Denmark – Sjælland

- France – Auvergne, Corsica, Franche-Comté, Languedoc-Roussillon, Limousin, Lorraine, Lower Normandy, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Picardy, Poitou-Charentes

- Germany – Lüneburg, all of the former East Germany sans Berlin (except Leipzig)

- Greece – Dytiki Makedonia, Ionia Nisia, Kriti, Peloponnisos, Sterea Ellada, Voreio Aigaio

- Italy – Abruzzo, Molise, Sardinia

- Malta – all

- Poland - none

- Portugal – Algarve

- Spain – Andalucía, Canarias, Castilla-La Mancha, Melilla, Murcia

- United Kingdom – Cumbria, Devon, East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire, Highlands and Islands, Lancashire, Lincolnshire, Merseyside, Northern Ireland, Shropshire and Staffordshire, South Yorkshire, Tees Valley and Durham

- Bulgaria – Southwestern region

More developed regions

[edit]This covers all European regions that are not covered elsewhere, namely those which have a GDP per capita above 90 percent of the EU average. The main aim of funding for these regions is to create jobs by promoting competitiveness and making the regions concerned more attractive to businesses and investors. Possible projects include developing clean transport, supporting research centres, universities, small businesses and start-ups, providing training, and creating jobs. Funding is managed through either the ERDF or the ESF.

In all regions, bank loans are the most prevalent type of external financing. In more developed regions, they account for 58% of finance.[19][13]

Areas designated as more developed regions from 2014 to 2020

[edit]- Austria – all (except Burgenland)

- Belgium – all of Flanders, Brussels, Walloon Brabant

- Cyprus – all

- Czech Republic – Prague

- Denmark – all (except Sjælland)

- Finland – all

- France – Alsace, Aquitaine, Burgundy, Brittany, Centre, Champagne-Ardenne, Île-de-France, Midi-Pyrénées, Pays de la Loire, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, Rhône-Alpes, Upper Normandy

- Germany – Berlin, Leipzig, all of the former West Germany (except Lüneburg)

- Greece – Attiki, Notio Aigaio

- Hungary – Közép-Magyarország

- Ireland – all

- Italy – Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Lazio, Liguria, Lombardy, Marche, Piedmont, South Tyrol, Trentino, Tuscany, Umbria, Valle d'Aosta, Veneto

- Luxembourg – all

- Netherlands – all

- Poland – the Warsaw Metro NUTS2 Unit carved out of Masovian Voivodeship

- Portugal – Lisbon region, Madeira

- Romania – Bucharest

- Slovakia – Bratislava

- Slovenia - Zahodna Slovenija

- Spain – Aragon, Asturias, Balearic Islands, Basque Country, Cantabria, Castilla y León, Catalonia, Ceuta, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid Region, Navarre, Valencian Community

- Sweden – all

- United Kingdom – all of London, South East England, and the East of England, plus Dorset, Somerset, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire, West Midlands, Leicestershire, Rutland, Northamptonshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, North Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear, Northumberland, South Western Scotland, Eastern Scotland, North Eastern Scotland and East Wales

European territorial cooperation

[edit]This objective aims to reduce the importance of borders within Europe – both between and within countries – by improving regional cooperation. It allows for three different types of cooperation: cross-border, transnational and interregional cooperation. The objective is currently by far the least important in pure financial terms, accounting for only 2.5% of the EU's regional policy budget. It is funded exclusively through the ERDF.

Instruments and funding

[edit]The cohesion policy accounts for almost one third of the EU's budget, equivalent to almost EUR 352 billion over seven years in 2014-2020,[22] and EUR 392 billion in 2021-2027,[1] dedicated to the promotion of economic development and job creation, and for helping communities and nations get ready for the European Union's transition to a more sustainable and digital economy.[23][24] Cohesion lending had a large percentage of contributions to climate and environmental goals in 2021 and 2022.[25] Sustainable energy and natural resources accounted for €10.2 billion, or 34% of overall European Investment Bank cohesion loans, compared to 26% for non-cohesion regions. 52% of loans in the European Union for sustainability (€19.6 billion) went to projects in cohesion areas.[26]

The main resource of EU's territorial cohesion policy is EU's structural funds. There are two structural funds available to all EU regions: the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)[27] and the European Social Fund (ESF).[28] The ERDF is intended to be used for the creation of infrastructure and productive job-creating investment and it is mainly for the businesses, while the ESF is meant to contribute to the integration of the unemployed populations into the work life via training measurements. The funds are managed and delivered in partnership between the European Commission, the Member States and stakeholders at the local and regional level. In the 2014–2020 funding period, money is allocated differently between regions that are deemed to be "more developed" (with GDP per capita over 90% of the EU average), "transition" (between 75% and 90%), and "less developed" (less than 75%), and additional funds are set aside for member states with GNI per capita under 90 percent of the EU average in the Cohesion Fund.[29] Funding for less developed regions, like the Convergence objective before it, aims to allow the regions affected to catch up with the EU's more prosperous regions, thereby reducing economic disparity within the European Union. Examples of types of projects funded under this objective include improving basic infrastructure, helping businesses, building or modernising waste and water treatment facilities, and improving access to high-speed Internet connections. Regional policy projects in less developed regions are supported by three European funds: the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF) and the Cohesion Fund.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) has pledged to increasing its support for certain regions in its Cohesion Orientation for 2021–2027.[30] Between 2023 and 2024, the Bank plans to allocate at least 40% of the overall finance it provides to projects in cohesion regions, increasing to at least 45% starting in 2025. The less developed areas of Europe will get at least half of this allocation, and increasing regions that receive its climate action and environmental loans.[31][32]

The European Investment Bank has given €44.7 billion to projects in cohesion areas for the European Union since 2021. Included in this is €24.8 billion in 2022 alone, or 46% of all EU signatures. From 2014 - 2020, they contributed a total of €123.8 billion to projects in cohesion areas.[33][34] Financial instruments from the Bank have so far helped around 6,600 projects in Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, Portugal, Lithuania, Romania, and Cyprus.[35] In 2022, the EIB Group contributed €28.4 billion to initiatives in cohesion areas and €16.2 billion in climate action and environmental sustainability.[36] 44% of the EIB Group's overall loan in the European Union in 2022—or €28.4 billion—went to projects in cohesion areas. In the same year, projects with a combined investment cost of €146 billion were backed by EIB loans across the EU.[37][38] For the EU as a whole, the European Investment Bank invested €16.2 billion in climate action and environmental sustainability in 2022 in cohesion areas. This is over half of the EU's total EIB funding for climate change and environmental sustainability.[39][40] In 2023, cohesion regions received 83% of the EIB's funding for urban and regional projects, and 65% of the funding for strategic transport projects was allocated to these areas.[41]

Also in 2023, the European Investment Fund spent €14.9 billion in cohesion areas, partnering with 300 institutions throughout Europe to provide finance for over 350 000 small firms, infrastructure projects, homes, and individuals. This resulted in €134 billion for the real economy.[42]

The European Union invested €14 billion, 49% of which focused on economic and social integration. These funds are intended to raise around €42.7 billion.[42]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- DG REGIO (2008). Working for the regions. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. ISBN 978-92-79-03776-4. Cat. No. KN-76-06-538-EN-C. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The EU's main investment policy". European Commission. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (4 July 2023). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2022. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5581-9.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "European Spatial Development Perspective". Archived 21 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "European Spatial Planning Observation Network". Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Is my region covered?, European Commission Regional Policy. Accessed 11 June 2011

- ^ Santos, E., Lisboa, I., Moreira, J., & Ribeiro, N. (2020, October). Regional Competitiveness and the Productivity Performance of Gazelles in Cultural Tourism. In International Conference on Tourism, Technology and Systems (pp. 114-124). Springer, Singapore.[1]

- ^ a b "Regional Cohesion in Europe 2021-2022". EIB.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Inforegio-Newsroom". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME policy responses". OECD. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (4 July 2023). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2022. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5581-9.

- ^ NEFI. "News". NEFI - Network of European Financial Institutions for SMEs. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "European Small Business Finance Outlook" (PDF). EIF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2016.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ "Ninth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion" (PDF).

- ^ a b Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ "Recent trends in female employment" (PDF). European Parliament.

- ^ a b "Regional Cohesion in Europe 2021-2022". EIB.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "EIB Group Activities in EU cohesion regions in 2021". www.eib.org. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Regional Cohesion in Europe 2021-2022". EIB.org. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Cohesion policy". European Commission Glossary.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (12 July 2022). Regional Cohesion in Europe 2021-2022: Evidence from the EIB Investment Survey. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5367-9.

- ^ "Cohesion Policy 2021-2027". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Special report: Climate spending in the 2014-2020 EU budget". op.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ "The European Regional Development Fund" Archived 1 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The European Social Fund" Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cohesion policy

- ^ "2021-2027: Cohesion policy EU budget initial allocations". cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (17 May 2023). "Cohesion and regional development Overview 2023".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Regions and cities team up with Commission and EIB in the race against clock to boost cohesion investment and recovery efforts for all citizens". cor.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (17 May 2023). "Cohesion and regional development Overview 2023".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Inforegio - Cohesion Fund". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (17 May 2023). "Cohesion and regional development Overview 2023".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bank, European Investment (4 July 2023). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2022. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5581-9.

- ^ "EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2022". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "Regions and cities team up with Commission and EIB in the race against clock to boost cohesion investment and recovery efforts for all citizens". cor.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (4 July 2023). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2022. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5581-9.

- ^ "Eighth National Communication and Fifth Biennial Report from the European Union under the UNFCCC" (PDF). unfccc.int. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

- ^ a b Bank, European Investment (15 July 2024). EIB Group activities in EU cohesion regions 2023. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5761-5.

External links

[edit]Regional policy of the European Union

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in the Treaty of Rome and Early Initiatives

The Treaty of Rome, signed on 25 March 1957 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany, and entering into force on 1 January 1958, laid the foundational objectives for what would evolve into the European Union's regional policy.[12] Its preamble committed signatories to reducing differences in levels of development and standards of living across regions to foster social progress and economic harmony.[13] Article 2 further specified promoting a harmonious development of economic activities, continuous and balanced expansion, accelerated improvement in living standards, and closer relations between Member States, implicitly acknowledging the need to address territorial imbalances arising from market integration.[14] While the treaty lacked dedicated regional funds or mechanisms—relying instead on the assumption that free trade and competition would naturally converge economies—it established the principle of solidarity to counteract disparities exacerbated by the common market.[15] Early initiatives in the European Economic Community (EEC) from the 1960s built on these principles through ad hoc and indirect instruments rather than a comprehensive policy framework. The European Social Fund (ESF), established in 1960 under Articles 123–125 of the Treaty, prioritized improving occupational adaptability, vocational training, and geographical/occupational mobility of workers to combat structural unemployment, with practical applications targeting high-unemployment regions like southern Italy's Mezzogiorno.[16] Complementing this, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), adopted in 1962, incorporated a guidance section within the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (FEOGA) to finance structural improvements, modernization, and diversification in less-favored rural areas, addressing agricultural backwardness in peripheral regions.[15] These funds, totaling modest allocations—ESF disbursed about 170 million units of account by 1970—served as precursors to targeted regional aid, though their impact was limited by national control over implementation and a focus on sector-specific rather than place-based interventions.[17] By the late 1960s, persistent regional divergences—evident in GDP per capita gaps, with Italy's southern regions lagging 40–50% behind the north—prompted institutional steps toward coordination.[18] The European Commission established a Directorate-General for Regional Policies and Coordination of Structural Policies in 1968 to analyze imbalances, advocate for investment in infrastructure, and integrate regional considerations into broader EEC decision-making.[14] This period's efforts, driven by advocacy from disparity-affected states like Italy, highlighted causal tensions between market liberalization and uneven development, setting the stage for demands for a dedicated fund amid the 1973 enlargement and oil crisis.[17]Evolution Through Enlargement and Crises

The first major enlargement of the European Communities in 1973, incorporating Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, highlighted regional disparities, particularly in Ireland, where GDP per capita lagged behind the community average, necessitating initial ad hoc interventions like the 1972 decision on regional development grants.[19] This prompted the creation of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in 1975 via Council Regulation (EEC) No 724/75, with an initial budget of 1.3 billion ECU for 1975-1977, aimed at supporting infrastructure in less-developed areas to mitigate uneven integration impacts.[20] Subsequent southern enlargements—Greece in 1981 and Spain and Portugal in 1986—exacerbated disparities, as these countries had average GDP per capita levels 55-68% below the community average, straining existing mechanisms and fueling debates on fiscal redistribution.[21] In response, the 1988 reform under the Delors I package restructured the Structural Funds, increasing their budget from 16 billion ECU (1987-1993) to emphasize concentration on Objective 1 regions (lagging areas), with integrated operations linking ERDF, European Social Fund (ESF), and European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF). The 1992 introduction of the Cohesion Fund, allocated 4.4 billion ECU for 1993-1999, targeted environmental and transport infrastructure in the four poorest members (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain) to facilitate Economic and Monetary Union convergence, reflecting causal links between enlargement-induced poverty traps and the need for compensatory transfers.[19] The 1995 accession of Austria, Finland, and Sweden introduced relatively affluent Nordic regions but minor peripheral disparities, prompting minor adjustments in the 1999 Berlin Council reforms for the 2000-2006 period, which allocated €213 billion overall and prioritized human resource development amid the 1992-1993 European Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis that widened regional unemployment gaps to 12 percentage points in some areas.[22] The transformative 2004 enlargement, adding ten Central and Eastern European states with GDP per capita averaging 40-50% of the EU-15 level, necessitated a scaled-up €347 billion budget for 2007-2013, shifting emphasis to convergence objectives covering 84% of the EU population and integrating pre-accession instruments like ISPA into mainstream cohesion funding to build administrative capacity and infrastructure, yielding post-enlargement GDP per capita gains of up to 20-30% in new members by 2019.[23] [24] Bulgaria and Romania's 2007 entry, followed by Croatia in 2013, further extended this framework, with conditionalities tied to rule-of-law reforms to address corruption risks in fund absorption.[25] Economic crises intersected with these expansions, amplifying adaptation needs; the 1973-1974 oil shock, doubling energy import costs and contracting GDP by 0.5-2% across members, exposed structural vulnerabilities in peripheral regions but elicited limited supranational response beyond national aids, underscoring early policy's reactive nature.[26] The 2008 global financial crisis, triggering a 4.5% EU GDP drop in 2009, prompted regulatory amendments like Commission Regulation (EC) No 397/2009, enabling 7% reprogramming flexibility for job preservation and SME liquidity, with €26 billion reallocated to counter-cyclical measures by 2011.[22] The ensuing Eurozone sovereign debt crisis (2009-2012), hitting cohesion-eligible states like Greece (25% GDP contraction) hardest, integrated macroeconomic conditionality into the 2014-2020 period via Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013, suspending funds for excessive deficits and enforcing reforms, though empirical data show cohesion investments mitigated divergence by sustaining 1-2% annual growth premiums in funded regions.[27] [28] The COVID-19 recession, with €100 billion in REACT-EU top-ups by 2021, further tested resilience, reinforcing performance-based allocations while empirical assessments indicate crises temporarily stalled but did not reverse long-term convergence trends, as disparities in GDP per capita fell from 30% (2000) to 24% (2021) between richest and poorest regions.[29]Shift from Redistribution to Performance-Based Approaches

The European Union's cohesion policy traditionally emphasized redistribution, allocating funds primarily to less-developed regions based on objective criteria such as GDP per capita below 75% of the EU average, unemployment rates, and population size, with the goal of narrowing economic disparities across member states.[1] This approach, dominant from the policy's inception in the 1970s through the 2007-2013 programming period, distributed over €347 billion in commitments, yet evaluations indicated limited long-term convergence, as some recipient regions experienced growth while others stagnated due to absorption issues and weak institutional capacity.[30] Critics argued that unconditional transfers often failed to address underlying structural weaknesses, prompting a reevaluation toward mechanisms that link funding to verifiable outcomes rather than need alone.[31] A pivotal shift occurred with the 2014-2020 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which introduced a mandatory performance framework (PF) for European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), including the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund.[30] The PF required programs to define specific output and result indicators, with annual implementation reports tracking progress against milestones; a performance reserve of 6% of each program's allocation—totaling approximately €20 billion across cohesion spending—was withheld and redistributed in 2019 to priorities meeting predefined thresholds, incentivizing efficient management and results-oriented spending.[32] Ex-ante conditionalities further enforced prerequisites, such as robust administrative capacity and alignment with national strategies, suspending funds if unmet, which aimed to mitigate risks of inefficient absorption observed in prior periods where up to 20% of funds went unspent in some countries.[33] This performance-based orientation intensified in the 2021-2027 MFF, allocating €392 billion to cohesion policy (including national co-financing exceeding €500 billion total), with enhanced conditionalities tying disbursements to achievement of specific objectives like green transition and digitalization under six policy goals.[2] While retaining eligibility-based formulas, up to 8% of allocations now hinge on performance assessments, integrated with tools like the Recovery and Resilience Facility, which employs milestones and targets for 100% of its €723 billion envelope, marking a broader EU trend toward results-driven investment amid critiques that pure redistribution yielded diminishing returns, with GDP convergence rates averaging only 0.5-1% annually in lagging regions pre-2014.[34] Empirical analyses confirm positive macroeconomic impacts from 2014-2020 investments, estimating GDP boosts of 0.5-1.2% in beneficiary regions, attributed partly to performance incentives that improved project selection and monitoring, though challenges persist in measuring long-term causality and addressing political influences on indicator design.[5][35]Legal and Conceptual Foundations

Territorial Cohesion as Defined in EU Treaties

The concept of territorial cohesion entered the European Union's legal framework as part of the broader objective of economic, social, and territorial cohesion through the Treaty of Lisbon, which amended the Treaties and entered into force on 1 December 2009.[36] Prior to this, cohesion policy under the Treaty on European Union (as established by the Maastricht Treaty of 1992) focused primarily on economic and social dimensions, with territorial aspects addressed informally through regional development initiatives but not explicitly enshrined.[36] Article 174 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which operationalizes this objective, states: "In view of the disparities between the levels of development of the various regions and the backward state in which some regions are, and bearing in mind that the abolition of obstacles to the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is liable to create or to aggravate disparities between the levels of development of the various regions, the Union shall aim at reducing disparities between the levels of development of the various regions and the backwardness of the least-favoured regions or islands, including rural areas."[37] This provision emphasizes the Union's role in addressing regional imbalances exacerbated by the internal market's dynamics, with particular attention to regions suffering from severe and permanent natural or demographic handicaps, such as northernmost regions with very low population density and island, cross-border, and mountain regions.[37] Complementing Article 174 TFEU, Article 3(3) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) identifies the promotion of economic, social, and territorial cohesion as essential to the Union's internal development and solidarity among Member States.[38] Protocol (No 28) annexed to the TFEU further reinforces this by committing the Union to consider economic, social, and territorial cohesion in its policies, underscoring the need for balanced territorial development to support the single market's functioning.[39] In treaty terms, territorial cohesion thus entails targeted actions to mitigate uneven regional growth, prioritizing equity in access to infrastructure, services, and opportunities across diverse geographies, without prescribing specific mechanisms beyond the imperative to strengthen overall cohesion and reduce specified disparities.[37] This definition has guided subsequent cohesion policy programming, linking treaty obligations to funding allocations aimed at less-favoured areas, though implementation remains subject to political negotiations among Member States.[40]Core Objectives and Principles Across Programming Periods

The European Union's cohesion policy, as the primary instrument of its regional policy, seeks to strengthen economic, social, and territorial cohesion by addressing disparities in development levels across regions and supporting the integration of less-developed areas into the single market.[41] These aims originate from the Treaty of Rome (1957) and were reinforced in subsequent treaties, particularly the Maastricht Treaty (1992), which elevated cohesion to a fundamental objective alongside economic and monetary union.[14] Empirical assessments indicate that while the policy has allocated over €1.5 trillion since 1989 to infrastructure, human capital, and innovation, its impact on convergence remains debated, with faster-growing regions often benefiting more due to absorption capacities and national complementarities.[42] Guiding principles, established in the 1988 reform and refined thereafter, include concentration, which prioritizes funding for the least-developed regions (e.g., at least 70% of resources in 2014–2020 targeted such areas); programming, mandating multi-annual operational programs co-financed by EU and national budgets and aligned with union-wide priorities rather than ad hoc projects; partnership, requiring involvement of regional, local, and civil society stakeholders in design, implementation, and evaluation to tailor interventions to territorial needs; and additionality, ensuring EU funds supplement domestic expenditures without substituting them.[43] These principles promote subsidiarity and proportionality, though implementation challenges, such as bureaucratic delays and uneven enforcement, have persisted across periods, as noted in European Court of Auditors reports.[42] Across programming periods, core objectives have evolved to integrate broader union goals while retaining the focus on disparity reduction:- 1989–1993: Emphasis on integrating structural funds for infrastructure and human resource development in Objective 1 regions (poorest areas with GDP per capita below 75% of EU average), marking the first multi-annual framework with ECU 64 billion allocated to foster convergence amid single market completion.[14]

- 1994–1999: Retained convergence for lagging regions while adding support for industrial conversion (Objective 2) and rural development, with funds doubled to ECU 168 billion under Maastricht criteria, incorporating sparsely populated areas post-enlargement preparations.[14]

- 2000–2006: Aligned with the Lisbon Strategy for knowledge-based growth, prioritizing innovation, entrepreneurship, and job creation (e.g., 25% of funds for adaptability and innovation), with €213 billion for existing members plus pre-accession aid, though mid-term reviews highlighted absorption issues in new entrants.[14]

- 2007–2013: Focused on sustainable growth and jobs per the renewed Lisbon agenda, mandating 25% allocation to R&D/innovation and 30% to environmental measures, within a €347 billion envelope emphasizing transparency and performance reserves.[14]

- 2014–2020: Oriented toward Europe 2020 targets for smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth, with thematic concentrations like 20% for low-carbon investments, though evaluations showed mixed convergence outcomes due to external shocks like the sovereign debt crisis.[44]

- 2021–2027: Streamlined to five policy objectives—a smarter Europe via innovation; a greener, carbon-neutral Europe; a more connected Europe through transport/energy; a more social Europe tackling unemployment/education; and a Europe closer to citizens via local development—totaling €392 billion, with mandatory climate (30–37%) and digital (20%) targets, amid post-COVID recovery and green transition imperatives.[44][41]

Regional Classification Criteria and Methodologies

The European Union's regional classification for cohesion policy relies on the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), a hierarchical system established by Eurostat to standardize regional divisions across member states for statistical and policy purposes. NUTS divides territories into levels, with NUTS 2 designated as the primary unit for defining eligibility and targeting cohesion funds, encompassing basic regions suitable for regional policy application; these typically range from 800,000 to 3 million inhabitants where possible, though administrative boundaries are prioritized for practicality.[45] Regions at this level are assessed using harmonized data from national accounts, ensuring comparability in metrics like gross domestic product (GDP).[46] Regions are categorized into three groups—less developed, transition, and more developed—primarily based on average GDP per capita in purchasing power standards (PPS) relative to the EU-27 average, calculated over a three-year reference period to smooth cyclical fluctuations; for the 2021–2027 programming period, this uses data from 2016–2018. Less developed regions have GDP per capita below 75% of the EU average, qualifying for the highest co-financing rates and comprehensive support; transition regions range from 75% to 100%, reflecting moderate disparities and eligibility for targeted investments; more developed regions exceed 100%, receiving limited funding focused on innovation and efficiency rather than convergence.[47][48] This threshold adjustment from prior periods (where transition was 75–90%) accommodates post-financial crisis realities and enlargement effects, aiming to broaden support amid stagnant convergence in some areas.[47][49] Methodologies incorporate additional qualifiers for specific vulnerabilities, such as population sparsity (under 8 inhabitants per km² or 12.5% in decline over three years), low population density (under 50 per km² with net migration loss), or outermost regions under Article 349 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which may override GDP thresholds for enhanced eligibility; these ensure tailored interventions beyond pure economic metrics.[48] Classifications are reviewed periodically, with transitions between categories triggering phasing-in or phasing-out mechanisms to avoid abrupt funding shifts—e.g., regions graduating from less developed status receive 66–100% of prior allocations initially. Data integrity is maintained through Eurostat validation of member state submissions, though critiques note potential manipulation via NUTS boundary revisions to influence eligibility, as observed in cases from Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania.[47][50] Overall, this GDP-centric approach, while empirically grounded in convergence theory, has faced scrutiny for over-relying on a single indicator that may undervalue non-monetary disparities like unemployment or infrastructure gaps.[46]Funding and Implementation Mechanisms

Budgetary Framework and Allocation Formulas

The budgetary framework for the European Union's regional policy, primarily implemented through Cohesion Policy, is embedded within the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which sets multi-annual spending limits across EU priorities. For the 2021-2027 programming period, Cohesion Policy receives €392 billion in EU commitments, representing approximately one-third of the total MFF and leveraging additional national co-financing to reach around €500 billion overall.[2] These resources are channeled mainly through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), and Cohesion Fund (CF), with supplementary allocations from the Just Transition Fund (JTF) for regions affected by decarbonization.[2] The framework emphasizes performance-based conditionalities, requiring Member States to meet milestones for disbursements, and aligns funding with EU-wide objectives such as smart growth, sustainability, and social inclusion.[51] Allocations to Member States follow the Berlin method, a formula adopted by the European Council in 1999 that uses objective, data-driven criteria to distribute funds based on relative economic disadvantage. The methodology calculates initial envelopes using a weighted combination of factors, with prosperity—measured as average GDP per capita (or GNI for some components) relative to the EU average over three years—accounting for about 81% of the weighting, while population contributes the remainder, adjusted for regional eligibility categories.[51] Additional premiums are applied for youth unemployment (up to €500 per excess unemployed person annually), low secondary education attainment, net migration inflows (3% weighting), and greenhouse gas emissions (1% weighting), reflecting updates introduced for 2021-2027 to address emerging disparities.[51] For the CF, which targets environmental infrastructure in lower-income states, the formula prioritizes population (50% weight) alongside GDP criteria, with eligibility limited to countries below 90% of EU GDP per capita.[51] Post-Member State allocation, funds are sub-distributed to regions according to NUTS-2 classifications: less developed (GDP <75% EU average, receiving ~75% of total funds), transition (75-90%), and more developed (>90%). Caps limit allocation increases to 8% and reductions to 24% compared to prior periods, with safety nets ensuring no Member State receives less than 85% of its 2014-2020 envelope in real terms, followed by political negotiations for final approval.[51] This approach, while formulaic, incorporates discretionary adjustments to balance equity and efficiency, though critics note it perpetuates historical spending patterns over pure need-based distribution.[51]| Factor | Weighting (Approximate) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita / GNI | 81% | Relative to EU average, using 3-year average; core measure of economic disadvantage |

| Population | 19% (varies by fund) | Eligible population in target regions; higher for CF |

| Youth Unemployment Premium | Variable premium | €500/year per person above EU average |

| Other (Education, Migration, Emissions) | 1-3% | Adjustments for low education (years 15-24), net migration, and climate impacts |