Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Positional notation

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Positional notation, also known as place-value notation, positional numeral system, or simply place value, usually denotes the extension to any base of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system (or decimal system). More generally, a positional system is a numeral system in which the contribution of a digit to the value of a number is the value of the digit multiplied by a factor determined by the position of the digit. In early numeral systems, such as Roman numerals, a digit has only one value: I means one, X means ten and C a hundred (however, the values may be modified when combined). In modern positional systems, such as the decimal system, the position of the digit means that its value must be multiplied by some value: in 555, the three identical symbols represent five hundreds, five tens, and five units, respectively, due to their different positions in the digit string.

The Babylonian numeral system, base 60, was the first positional system to be developed, and its influence is present today in the way time and angles are counted in tallies related to 60, such as 60 minutes in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle. The Inca used knots tied in a decimal positional system to store numbers and other values in quipu cords.

Today, the Hindu–Arabic numeral system (base ten) is the most commonly used system globally. However, the binary numeral system (base two) is used in almost all computers and electronic devices because it is easier to implement efficiently in electronic circuits.

Systems with negative base, complex base or negative digits have been described. Most of them do not require a minus sign for designating negative numbers.

The use of a radix point (decimal point in base ten), extends to include fractions and allows the representation of any real number with arbitrary accuracy. With positional notation, arithmetical computations are much simpler than with any older numeral system; this led to the rapid spread of the notation when it was introduced in western Europe.

History

[edit]

Today, the base-10 (decimal) system, which is presumably motivated by counting with the ten fingers, is ubiquitous. Other bases have been used in the past, and some continue to be used today. For example, the Babylonian numeral system, credited as the first positional numeral system, was base-60. However, it lacked a real zero. Initially inferred only from context, later, by about 700 BC, zero came to be indicated by a "space" or a "punctuation symbol" (such as two slanted wedges) between numerals.[1] It was a placeholder rather than a true zero because it was not used alone or at the end of a number. Numbers like 2 and 120 (2×60) looked the same because the larger number lacked a final placeholder. Only context could differentiate them.

The polymath Archimedes (ca. 287–212 BC) invented a decimal positional system based on 108 in his Sand Reckoner;[2] 19th century German mathematician Carl Gauss lamented how science might have progressed had Archimedes only made the leap to something akin to the modern decimal system.[3] Hellenistic and Roman astronomers used a base-60 system based on the Babylonian model (see Greek numerals § Zero).

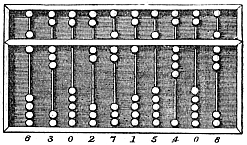

Before positional notation became standard, simple additive systems (sign-value notation) such as Roman numerals or Chinese numerals were used, and accountants in the past used the abacus or stone counters to do arithmetic until the introduction of positional notation.[4]

Lower row horizontal form

Counting rods and most abacuses have been used to represent numbers in a positional numeral system. With counting rods or abacus to perform arithmetic operations, the writing of the starting, intermediate and final values of a calculation could easily be done with a simple additive system in each position or column. This approach required no memorization of tables (as does positional notation) and could produce practical results quickly.

The oldest extant positional notation system is either that of Chinese rod numerals, used from at least the early 8th century, or perhaps Khmer numerals, showing possible usages of positional-numbers in the 7th century. Khmer numerals and other Indian numerals originate with the Brahmi numerals of about the 3rd century BC, which symbols were, at the time, not used positionally. Medieval Indian numerals are positional, as are the derived Arabic numerals, recorded from the 10th century.

After the French Revolution (1789–1799), the new French government promoted the extension of the decimal system.[5] Some of those pro-decimal efforts—such as decimal time and the decimal calendar—were unsuccessful. Other French pro-decimal efforts—currency decimalisation and the metrication of weights and measures—spread widely out of France to almost the whole world.

History of positional fractions

[edit]Decimal fractions were first developed and used by the Chinese in the form of rod calculus in the 1st century BC, and then spread to the rest of the world.[6][7] J. Lennart Berggren notes that positional decimal fractions were used being, in Damascus, by mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi, in the mid 10th century.[8] The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils used decimal fractions around 1350, but did not develop any notation to represent them.[9] The Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī similarly adopted their use in the 15th century.[8] Al Khwarizmi introduced fractions to Islamic countries in the early 9th century; his fraction presentation was similar to the traditional Chinese mathematical fractions from Sunzi Suanjing.[10] This form of fraction with numerator on top and denominator at bottom without a horizontal bar was also used by 10th century Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi and 15th century Jamshīd al-Kāshī's work "Arithmetic Key".[10][11]

| Number | 184.54290 |

|---|---|

| Simon Stevin's notation | 184⓪5①4②2③9④0 |

The adoption of the decimal representation of numbers less than one, a fraction, is often credited to Simon Stevin through his textbook De Thiende;[12] but both Stevin and E. J. Dijksterhuis indicate that Regiomontanus contributed to the European adoption of general decimals:[13]: 17, 18

European mathematicians, when taking over from the Hindus, via the Arabs, the idea of positional value for integers, neglected to extend this idea to fractions. For some centuries they confined themselves to using common and sexagesimal fractions ... This half-heartedness has never been completely overcome, and sexagesimal fractions still form the basis of our trigonometry, astronomy and measurement of time.

... Mathematicians sought to avoid fractions by taking the radius R equal to a number of units of length of the form 10n and then assuming for n so great an integral value that all occurring quantities could be expressed with sufficient accuracy by integers.

The first to apply this method was the German astronomer Regiomontanus. To the extent that he expressed goniometrical line-segments in a unit R/10n, Regiomontanus may be called an anticipator of the doctrine of decimal positional fractions.

In the estimation of Dijksterhuis, "after the publication of De Thiende only a small advance was required to establish the complete system of decimal positional fractions, and this step was taken promptly by a number of writers ... next to Stevin the most important figure in this development was Regiomontanus." Dijksterhuis noted that [Stevin] "gives full credit to Regiomontanus for his prior contribution, saying that the trigonometric tables of the German astronomer actually contain the whole theory of 'numbers of the tenth progress'."[13]: 19

Mathematics

[edit]Base of the numeral system

[edit]In mathematical numeral systems the radix r is usually the number of unique digits, including zero, that a positional numeral system uses to represent numbers. In some cases, such as with a negative base, the radix is the absolute value of the base b. For example, for the decimal system the radix (and base) is ten, because it uses the ten digits from 0 through 9. When a number "hits" 9, the next number will not be another different symbol, but a "1" followed by a "0". In binary, the radix is two, since after it hits "1", instead of "2" or another written symbol, it jumps straight to "10", followed by "11" and "100".

The highest symbol of a positional numeral system usually has the value one less than the value of the radix of that numeral system. The standard positional numeral systems differ from one another only in the base they use.

The radix is an integer that is greater than 1, since a radix of zero would not have any digits, and a radix of 1 would only have the zero digit. Negative bases are rarely used. In a system with more than unique digits, numbers may have many different possible representations.

It is important that the radix is finite, from which follows that the number of digits is quite low. Otherwise, the length of a numeral would not necessarily be logarithmic in its size.

(In certain non-standard positional numeral systems, including bijective numeration, the definition of the base or the allowed digits deviates from the above.)

In standard base-ten (decimal) positional notation, there are ten decimal digits and the number

- .

In standard base-sixteen (hexadecimal), there are the sixteen hexadecimal digits (0–9 and A–F) and the number

where B represents the number eleven as a single symbol.

In general, in base-b, there are b digits and the number

has Note that represents a sequence of digits, not multiplication.

Notation

[edit]When describing base in mathematical notation, the letter b is generally used as a symbol for this concept, so, for a binary system, b equals 2. Another common way of expressing the base is writing it as a decimal subscript after the number that is being represented (this notation is used in this article). 11110112 implies that the number 1111011 is a base-2 number, equal to 12310 (a decimal notation representation), 1738 (octal) and 7B16 (hexadecimal). In books and articles, when using initially the written abbreviations of number bases, the base is not subsequently printed: it is assumed that binary 1111011 is the same as 11110112.

The base b may also be indicated by the phrase "base-b". So binary numbers are "base-2"; octal numbers are "base-8"; decimal numbers are "base-10"; and so on.

To a given radix b the set of digits {0, 1, ..., b−2, b−1} is called the standard set of digits. Thus, binary numbers have digits {0, 1}; decimal numbers have digits {0, 1, 2, ..., 8, 9}; and so on. Therefore, the following are notational errors: 522, 22, 1A9. (In all cases, one or more digits is not in the set of allowed digits for the given base.)

Exponentiation

[edit]Positional numeral systems work using exponentiation of the base. A digit's value is the digit multiplied by the value of its place. Place values are the number of the base raised to the nth power, where n is the number of other digits between a given digit and the radix point. If a given digit is on the left hand side of the radix point (i.e. its value is an integer) then n is positive or zero; if the digit is on the right hand side of the radix point (i.e., its value is fractional) then n is negative.

As an example of usage, the number 465 in its respective base b (which must be at least base 7 because the highest digit in it is 6) is equal to:

If the number 465 was in base-10, then it would equal:

If however, the number were in base 7, then it would equal:

10b = b for any base b, since 10b = 1×b1 + 0×b0. For example, 102 = 2; 103 = 3; 1016 = 1610. Note that the last "16" is indicated to be in base 10. The base makes no difference for one-digit numerals.

This concept can be demonstrated using a diagram. One object represents one unit. When the number of objects is equal to or greater than the base b, then a group of objects is created with b objects. When the number of these groups exceeds b, then a group of these groups of objects is created with b groups of b objects; and so on. Thus the same number in different bases will have different values:

241 in base 5: 2 groups of 52 (25) 4 groups of 5 1 group of 1 ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo + + o ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo

241 in base 8: 2 groups of 82 (64) 4 groups of 8 1 group of 1 oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo + + o oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo oooooooo

The notation can be further augmented by allowing a leading minus sign. This allows the representation of negative numbers. For a given base, every representation corresponds to exactly one real number and every real number has at least one representation. The representations of rational numbers are those representations that are finite, use the bar notation, or end with an infinitely repeating cycle of digits.

Digits and numerals

[edit]A digit is a symbol that is used for positional notation, and a numeral consists of one or more digits used for representing a number with positional notation. Today's most common digits are the decimal digits "0", "1", "2", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", and "9". The distinction between a digit and a numeral is most pronounced in the context of a number base.

A non-zero numeral with more than one digit position will mean a different number in a different number base, but in general, the digits will mean the same.[14] For example, the base-8 numeral 238 contains two digits, "2" and "3", and with a base number (subscripted) "8". When converted to base-10, the 238 is equivalent to 1910, i.e. 238 = 1910. In our notation here, the subscript "8" of the numeral 238 is part of the numeral, but this may not always be the case.

Imagine the numeral "23" as having an ambiguous base number. Then "23" could likely be any base, from base-4 up. In base-4, the "23" means 1110, i.e. 234 = 1110. In base-60, the "23" means the number 12310, i.e. 2360 = 12310. The numeral "23" then, in this case, corresponds to the set of base-10 numbers {11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, ..., 121, 123} while its digits "2" and "3" always retain their original meaning: the "2" means "two of", and the "3" means "three of".

In certain applications when a numeral with a fixed number of positions needs to represent a greater number, a higher number-base with more digits per position can be used. A three-digit, decimal numeral can represent only up to 999. But if the number-base is increased to 11, say, by adding the digit "A", then the same three positions, maximized to "AAA", can represent a number as great as 1330. We could increase the number base again and assign "B" to 11, and so on (but there is also a possible encryption between number and digit in the number-digit-numeral hierarchy). A three-digit numeral "ZZZ" in base-60 could mean 215999. If we use the entire collection of our alphanumerics we could ultimately serve a base-62 numeral system, but we remove two digits, uppercase "I" and uppercase "O", to reduce confusion with digits "1" and "0".[15] We are left with a base-60, or sexagesimal numeral system utilizing 60 of the 62 standard alphanumerics. (But see Sexagesimal system below.) In general, the number of possible values that can be represented by a digit number in base is .

The common numeral systems in computer science are binary (radix 2), octal (radix 8), and hexadecimal (radix 16). In binary only digits "0" and "1" are in the numerals. In the octal numerals, are the eight digits 0–7. Hex is 0–9 A–F, where the ten numerics retain their usual meaning, and the alphabetics correspond to values 10–15, for a total of sixteen digits. The numeral "10" is binary numeral "2", octal numeral "8", or hexadecimal numeral "16".

Radix point

[edit]The notation can be extended into the negative exponents of the base b. Thereby the so-called radix point, mostly ».«, is used as separator of the positions with non-negative from those with negative exponent.

Numbers that are not integers use places beyond the radix point. For every position behind this point (and thus after the units digit), the exponent n of the power bn decreases by 1 and the power approaches 0. For example, the number 2.35 is equal to:

Sign

[edit]If the base and all the digits in the set of digits are non-negative, negative numbers cannot be expressed. To overcome this, a minus sign, here −, is added to the numeral system. In the usual notation it is prepended to the string of digits representing the otherwise non-negative number.

Base conversion

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2017) |

The conversion to a base of an integer n represented in base can be done by a succession of Euclidean divisions by the right-most digit in base is the remainder of the division of n by the second right-most digit is the remainder of the division of the quotient by and so on. The left-most digit is the last quotient. In general, the kth digit from the right is the remainder of the division by of the (k−1)th quotient.

For example: converting A10BHex to decimal (41227):

0xA10B/10 = Q: 0x101A R: 7 (ones place)

0x101A/10 = Q: 0x19C R: 2 (tens place)

0x19C/10 = Q: 0x29 R: 2 (hundreds place)

0x29/10 = Q: 0x4 R: 1 ...

4

When converting to a larger base (such as from binary to decimal), the remainder represents as a single digit, using digits from . For example: converting 0b11111001 (binary) to 249 (decimal):

0b11111001/10 = Q: 0b11000 R: 0b1001 (0b1001 = "9" for ones place)

0b11000/10 = Q: 0b10 R: 0b100 (0b100 = "4" for tens)

0b10/10 = Q: 0b0 R: 0b10 (0b10 = "2" for hundreds)

For the fractional part, conversion can be done by taking digits after the radix point (the numerator), and dividing it by the implied denominator in the target radix. Approximation may be needed due to a possibility of non-terminating digits if the reduced fraction's denominator has a prime factor other than any of the base's prime factor(s) to convert to. For example, 0.1 in decimal (1/10) is 0b1/0b1010 in binary, by dividing this in that radix, the result is 0b0.00011 (because one of the prime factors of 10 is 5). For more general fractions and bases see the algorithm for positive bases.

Alternatively, Horner's method can be used for base conversion using repeated multiplications, with the same computational complexity as repeated divisions.[16] A number in positional notation can be thought of as a polynomial, where each digit is a coefficient. Coefficients can be larger than one digit, so an efficient way to convert bases is to convert each digit, then evaluate the polynomial via Horner's method within the target base. Converting each digit is a simple lookup table, removing the need for expensive division or modulus operations; and multiplication by x becomes right-shifting. However, other polynomial evaluation algorithms would work as well, like repeated squaring for single or sparse digits. Example:

Convert 0xA10B to 41227 A10B = (10*16^3) + (1*16^2) + (0*16^1) + (11*16^0)

Lookup table: 0x0 = 0 0x1 = 1 ... 0x9 = 9 0xA = 10 0xB = 11 0xC = 12 0xD = 13 0xE = 14 0xF = 15 Therefore 0xA10B's decimal digits are 10, 1, 0, and 11.

Lay out the digits out like this. The most significant digit (10) is "dropped": 10 1 0 11 <- Digits of 0xA10B

---------------

10

Then we multiply the bottom number from the source base (16), the product is placed under the next digit of the source value, and then add:

10 1 0 11

160

---------------

10 161

Repeat until the final addition is performed:

10 1 0 11

160 2576 41216

---------------

10 161 2576 41227

and that is 41227 in decimal.

Convert 0b11111001 to 249 Lookup table: 0b0 = 0 0b1 = 1

Result:

1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 <- Digits of 0b11111001

2 6 14 30 62 124 248

-------------------------

1 3 7 15 31 62 124 249

Terminating fractions

[edit]The numbers which have a finite representation form the semiring

More explicitly, if is a factorization of into the primes with exponents ,[17] then with the non-empty set of denominators we have

where is the group generated by the and is the so-called localization of with respect to .

The denominator of an element of contains if reduced to lowest terms only prime factors out of . This ring of all terminating fractions to base is dense in the field of rational numbers . Its completion for the usual (Archimedean) metric is the same as for , namely the real numbers . So, if then has not to be confused with , the discrete valuation ring for the prime , which is equal to with .

If divides , we have

Infinite representations

[edit]Rational numbers

[edit]The representation of non-integers can be extended to allow an infinite string of digits beyond the point. For example, 1.12112111211112 ... base-3 represents the sum of the infinite series:

Since a complete infinite string of digits cannot be explicitly written, the trailing ellipsis (...) designates the omitted digits, which may or may not follow a pattern of some kind. One common pattern is when a finite sequence of digits repeats infinitely. This is designated by drawing a vinculum across the repeating block:[18]

This is the repeating decimal notation (to which there does not exist a single universally accepted notation or phrasing). For base 10 it is called a repeating decimal or recurring decimal.

An irrational number has an infinite non-repeating representation in all integer bases. Whether a rational number has a finite representation or requires an infinite repeating representation depends on the base. For example, one third can be represented by:

-

- or, with the base implied:

- (see also 0.999...)

For integers p and q with gcd (p, q) = 1, the fraction p/q has a finite representation in base b if and only if each prime factor of q is also a prime factor of b.

For a given base, any number that can be represented by a finite number of digits (without using the bar notation) will have multiple representations, including one or two infinite representations:

- A finite or infinite number of zeroes can be appended:

- The last non-zero digit can be reduced by one and an infinite string of digits, each corresponding to one less than the base, are appended (or replace any following zero digits):

- (see also 0.999...)

Irrational numbers

[edit]A (real) irrational number has an infinite non-repeating representation in all integer bases.[19]

Examples are the non-solvable nth roots

with and y ∉ Q, numbers which are called algebraic, or numbers like

which are transcendental. The number of transcendentals is uncountable and the sole way to write them down with a finite number of symbols is to give them a symbol or a finite sequence of symbols.

Applications

[edit]Decimal system

[edit]In the decimal (base-10) Hindu–Arabic numeral system, each position starting from the right is a higher power of 10. The first position represents 100 (1), the second position 101 (10), the third position 102 (10 × 10 or 100), the fourth position 103 (10 × 10 × 10 or 1000), and so on.

Fractional values are indicated by a separator, which can vary in different locations. Usually this separator is a period or full stop, or a comma. Digits to the right of it are multiplied by 10 raised to a negative power or exponent. The first position to the right of the separator indicates 10−1 (0.1), the second position 10−2 (0.01), and so on for each successive position.

As an example, the number 2674 in a base-10 numeral system is:

- (2 × 103) + (6 × 102) + (7 × 101) + (4 × 100)

or

- (2 × 1000) + (6 × 100) + (7 × 10) + (4 × 1).

Sexagesimal system

[edit]The sexagesimal or base-60 system was used for the integral and fractional portions of Babylonian numerals and other Mesopotamian systems, by Hellenistic astronomers using Greek numerals for the fractional portion only, and is still used for modern time and angles, but only for minutes and seconds. However, not all of these uses were positional.

Modern time separates each position by a colon or a prime symbol. For example, the time might be 10:25:59 (10 hours 25 minutes 59 seconds). Angles use similar notation. For example, an angle might be 10°25′59″ (10 degrees 25 minutes 59 seconds). In both cases, only minutes and seconds use sexagesimal notation—angular degrees can be larger than 59 (one rotation around a circle is 360°, two rotations are 720°, etc.), and both time and angles use decimal fractions of a second.[citation needed] This contrasts with the numbers used by Hellenistic and Renaissance astronomers, who used thirds, fourths, etc. for finer increments. Where we might write 10°25′59.392″, they would have written 10°25′59′′23′′′31′′′′12′′′′′ or 10°25i59ii23iii31iv12v.

Using a digit set of digits with upper and lowercase letters allows short notation for sexagesimal numbers, e.g. 10:25:59 becomes 'ARz' (by omitting I and O, but not i and o), which is useful for use in URLs, etc., but it is not very intelligible to humans.

In the 1930s, Otto Neugebauer introduced a modern notational system for Babylonian and Hellenistic numbers that substitutes modern decimal notation from 0 to 59 in each position, while using a semicolon (;) to separate the integral and fractional portions of the number and using a comma (,) to separate the positions within each portion.[20] For example, the mean synodic month used by both Babylonian and Hellenistic astronomers and still used in the Hebrew calendar is 29;31,50,8,20 days, and the angle used in the example above would be written 10;25,59,23,31,12 degrees.

Computing

[edit]In computing, the binary (base-2), octal (base-8) and hexadecimal (base-16) bases are most commonly used. Computers, at the most basic level, deal only with sequences of conventional zeroes and ones, thus it is easier in this sense to deal with powers of two. The hexadecimal system is used as "shorthand" for binary—every 4 binary digits (bits) relate to one and only one hexadecimal digit. In hexadecimal, the six digits after 9 are denoted by A, B, C, D, E, and F (and sometimes a, b, c, d, e, and f).

The octal numbering system is also used as another way to represent binary numbers. In this case the base is 8 and therefore only digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are used. When converting from binary to octal every 3 bits relate to one and only one octal digit.

Hexadecimal, decimal, octal, and a wide variety of other bases have been used for binary-to-text encoding, implementations of arbitrary-precision arithmetic, and other applications.

For a list of bases and their applications, see list of numeral systems.

Other bases in human language

[edit]Base-12 systems (duodecimal or dozenal) have been popular because multiplication and division are easier than in base-10, with addition and subtraction being just as easy. Twelve is a useful base because it has many factors. It is the smallest common multiple of one, two, three, four and six. There is still a special word for "dozen" in English, and by analogy with the word for 102, hundred, commerce developed a word for 122, gross. The standard 12-hour clock and common use of 12 in English units emphasize the utility of the base. In addition, prior to its conversion to decimal, the old British currency Pound Sterling (GBP) partially used base-12; there were 12 pence (d) in a shilling (s), 20 shillings in a pound (£), and therefore 240 pence in a pound. Hence the term LSD or, more properly, £sd.

The Maya civilization and other civilizations of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica used base-20 (vigesimal), as did several North American tribes (two being in southern California). Evidence of base-20 counting systems is also found in the languages of central and western Africa.

Remnants of a Gaulish base-20 system also exist in French, as seen today in the names of the numbers from 60 through 99. For example, sixty-five is soixante-cinq (literally, "sixty [and] five"), while seventy-five is soixante-quinze (literally, "sixty [and] fifteen"). Furthermore, for any number between 80 and 99, the "tens-column" number is expressed as a multiple of twenty. For example, eighty-two is quatre-vingt-deux (literally, four twenty[s] [and] two), while ninety-two is quatre-vingt-douze (literally, four twenty[s] [and] twelve). In Old French, forty was expressed as two twenties and sixty was three twenties, so that fifty-three was expressed as two twenties [and] thirteen, and so on.

In English the same base-20 counting appears in the use of "scores". Although mostly historical, it is occasionally used colloquially. Verse 10 of Psalm 90 in the King James Version of the Bible starts: "The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow". The Gettysburg Address starts: "Four score and seven years ago".

The Irish language also used base-20 in the past, twenty being fichid, forty dhá fhichid, sixty trí fhichid and eighty ceithre fhichid. A remnant of this system may be seen in the modern word for 40, daoichead.

The Welsh language continues to use a base-20 counting system, particularly for the age of people, dates and in common phrases. 15 is also important, with 16–19 being "one on 15", "two on 15" etc. 18 is normally "two nines". A decimal system is commonly used.

The Inuit languages use a base-20 counting system. Students from Kaktovik, Alaska invented a base-20 numeral system in 1994[21]

Danish numerals display a similar base-20 structure.

The Māori language of New Zealand also has evidence of an underlying base-20 system as seen in the terms Te Hokowhitu a Tu referring to a war party (literally "the seven 20s of Tu") and Tama-hokotahi, referring to a great warrior ("the one man equal to 20").

The binary system was used in the Egyptian Old Kingdom, 3000 BC to 2050 BC. It was cursive by rounding off rational numbers smaller than 1 to 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64, with a 1/64 term thrown away (the system was called the Eye of Horus).

A number of Australian Aboriginal languages employ binary or binary-like counting systems. For example, in Kala Lagaw Ya, the numbers one through six are urapon, ukasar, ukasar-urapon, ukasar-ukasar, ukasar-ukasar-urapon, ukasar-ukasar-ukasar.

North and Central American natives used base-4 (quaternary) to represent the four cardinal directions. Mesoamericans tended to add a second base-5 system to create a modified base-20 system.

A base-5 system (quinary) has been used in many cultures for counting. Plainly it is based on the number of digits on a human hand. It may also be regarded as a sub-base of other bases, such as base-10, base-20, and base-60.

A base-8 system (octal) was devised by the Yuki tribe of Northern California, who used the spaces between the fingers to count, corresponding to the digits one through eight.[22] There is also linguistic evidence which suggests that the Bronze Age Proto-Indo Europeans (from whom most European and Indic languages descend) might have replaced a base-8 system (or a system which could only count up to 8) with a base-10 system. The evidence is that the word for 9, newm, is suggested by some to derive from the word for "new", newo-, suggesting that the number 9 had been recently invented and called the "new number".[23]

Many ancient counting systems use five as a primary base, almost surely coming from the number of fingers on a person's hand. Often these systems are supplemented with a secondary base, sometimes ten, sometimes twenty. In some African languages the word for five is the same as "hand" or "fist" (Dyola language of Guinea-Bissau, Banda language of Central Africa). Counting continues by adding 1, 2, 3, or 4 to combinations of 5, until the secondary base is reached. In the case of twenty, this word often means "man complete". This system is referred to as quinquavigesimal. It is found in many languages of the Sudan region.

The Telefol language, spoken in Papua New Guinea, is notable for possessing a base-27 numeral system.

Non-standard positional numeral systems

[edit]Interesting properties exist when the base is not fixed or positive and when the digit symbol sets denote negative values. There are many more variations. These systems are of practical and theoretic value to computer scientists.

Balanced ternary[24] uses a base of 3 but the digit set is {1,0,1} instead of {0,1,2}. The "1" has an equivalent value of −1. The negation of a number is easily formed by switching the on the 1s. This system can be used to solve the balance problem, which requires finding a minimal set of known counter-weights to determine an unknown weight. Weights of 1, 3, 9, ..., 3n known units can be used to determine any unknown weight up to 1 + 3 + ... + 3n units. A weight can be used on either side of the balance or not at all. Weights used on the balance pan with the unknown weight are designated with 1, with 1 if used on the empty pan, and with 0 if not used. If an unknown weight W is balanced with 3 (31) on its pan and 1 and 27 (30 and 33) on the other, then its weight in decimal is 25 or 1011 in balanced base-3.

- 10113 = 1 × 33 + 0 × 32 − 1 × 31 + 1 × 30 = 25.

The factorial number system uses a varying radix, giving factorials as place values; they are related to Chinese remainder theorem and residue number system enumerations. This system effectively enumerates permutations. A derivative of this uses the Towers of Hanoi puzzle configuration as a counting system. The configuration of the towers can be put into 1-to-1 correspondence with the decimal count of the step at which the configuration occurs and vice versa.

| Decimal equivalents | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced base 3 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 111 | 110 | 111 | 101 |

| Base −2 | 1101 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 110 | 111 | 100 | 101 | 11010 | 11011 | 11000 |

| Factoroid | 0 | 10 | 100 | 110 | 200 | 210 | 1000 | 1010 | 1100 |

Non-positional positions

[edit]Each position does not need to be positional itself. Babylonian sexagesimal numerals were positional, but in each position were groups of two kinds of wedges representing ones and tens (a narrow vertical wedge | for the one and an open left pointing wedge ⟨ for the ten) — up to 5+9=14 symbols per position (i.e. 5 tens ⟨⟨⟨⟨⟨ and 9 ones ||||||||| grouped into one or two near squares containing up to three tiers of symbols, or a place holder (⑊) for the lack of a position).[25] Hellenistic astronomers used one or two alphabetic Greek numerals for each position (one chosen from 5 letters representing 10–50 and/or one chosen from 9 letters representing 1–9, or a zero symbol).[26]

See also

[edit]Examples:

Related topics:

- Algorism

- Hindu–Arabic numeral system

- Mixed radix

- Non-standard positional numeral systems

- Scientific notation

Other:

Notes

[edit]- ^ Kaplan, Robert (2000). The Nothing That Is: A Natural History of Zero. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 11–12 – via archive.org.

- ^ "Greek numerals". Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Menninger, Karl: Zahlwort und Ziffer. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Zahl, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 3rd. ed., 1979, ISBN 3-525-40725-4, pp. 150–153

- ^ Ifrah, page 187

- ^ L. F. Menabrea. Translated by Ada Augusta, Countess of Lovelace. "Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage" Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 1842.

- ^ Lam Lay Yong, "The Development of Hindu-Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic", Chinese Science, 1996 p38, Kurt Vogel notation

- ^ Joseph Needham (1959). "Decimal System". Science and Civilisation in China, Volume III, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ^ Gandz, S.: The invention of the decimal fractions and the application of the exponential calculus by Immanuel Bonfils of Tarascon (c. 1350), Isis 25 (1936), 16–45.

- ^ a b Lam Lay Yong, "The Development of Hindu-Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic", Chinese Science, 1996, p. 38, Kurt Vogel notation

- ^ Lay Yong, Lam. "A Chinese Genesis, Rewriting the history of our numeral system". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 38: 101–108.

- ^ B. L. van der Waerden (1985). A History of Algebra. From Khwarizmi to Emmy Noether. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ a b E. J. Dijksterhuis (1970) Simon Stevin: Science in the Netherlands around 1600, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dutch original 1943

- ^ The digit will retain its meaning in other number bases, in general, because a higher number base would normally be a notational extension of the lower number base in any systematic organization. In the mathematical sciences there is virtually only one positional-notation numeral system for each base below 10, and this extends with few, if insignificant, variations on the choice of alphabetic digits for those bases above 10.

- ^ We do not usually remove the lowercase digits "l" and lowercase "o", for in most fonts they are discernible from the digits "1" and "0".

- ^ Collins, G. E.; Mignotte, M.; Winkler, F. (1983). "Arithmetic in basic algebraic domains" (PDF). In Buchberger, Bruno; Collins, George Edwin; Loos, Rüdiger; Albrecht, Rudolf (eds.). Computer Algebra: Symbolic and Algebraic Computation. Computing Supplementa. Vol. 4. Vienna: Springer. pp. 189–220. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7551-4_13. ISBN 3-211-81776-X. MR 0728973.

- ^ The exact size of the does not matter. They only have to be ≥ 1.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Vinculum". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "Irrational Numbers: Definition, Examples and Properties". flamath.com. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Neugebauer, Otto; Sachs, Abraham Joseph; Götze, Albrecht (1945), Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, American Oriental Series, vol. 29, New Haven: American Oriental Society and the American Schools of Oriental Research, p. 2, ISBN 9780940490291, archived from the original on 1 October 2016, retrieved 18 September 2019

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bartley, Wm. Clark (January–February 1997). "Making the Old Way Count" (PDF). Sharing Our Pathways. 2 (1): 12–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Barrow, John D. (1992), Pi in the sky: counting, thinking, and being, Clarendon Press, p. 38, ISBN 9780198539568.

- ^ (Mallory & Adams 1997) Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture

- ^ Knuth, pages 195–213

- ^ Ifrah, pages 326, 379

- ^ Ifrah, pages 261–264

References

[edit]- O'Connor, John; Robertson, Edmund (December 2000). "Babylonian Numerals". Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Kadvany, John (December 2007). "Positional Value and Linguistic Recursion". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 35 (5–6): 487–520. doi:10.1007/s10781-007-9025-5. S2CID 52885600.

- Knuth, Donald (1997). The art of Computer Programming. Vol. 2. Addison-Wesley. pp. 195–213. ISBN 0-201-89684-2.

- Ifrah, George (2000). The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-37568-3.

- Kroeber, Alfred (1976) [1925]. Handbook of the Indians of California. Courier Dover Publications. p. 176. ISBN 9780486233680.

External links

[edit]Positional notation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Positional notation, also known as place-value notation, is a numeral system in which the value of each digit in a number is determined by its position relative to a radix point, allowing for efficient representation of numerical values through powers of a chosen base.[3] This contrasts with non-positional systems, such as Roman numerals, where symbols represent fixed values regardless of their position, complicating arithmetic operations due to the lack of inherent place value.[3] The core principle of positional notation is that each digit position corresponds to a specific power of the base, with the rightmost position representing the base raised to the power of zero (units place). For example, in base 10 (decimal), the positions from right to left denote (units), (tens), (hundreds), and so on.[3] Digits in these positions range from 0 to one less than the base, enabling compact encoding of large numbers. For an integer in base , the value is given by the formula: where are the digits, each satisfying .[3] This summation principle underpins the system's scalability and ease of computation. A representative example is the decimal number 123, parsed as .[3]Place Value System

In positional notation, the value of a numeral is determined by the position of each digit relative to the others, with the rightmost digit representing the least significant place, corresponding to the base raised to the power of zero (). Each subsequent position to the left increases in significance by successive powers of the base , such that the -th position from the right has a place value of . This mechanism allows a single digit string to encode a wide range of values through weighted summation, where the total value is the sum of each digit multiplied by its positional weight.[4][5] This place value system provides a significant efficiency advantage over additive numeral systems, such as Roman numerals, by enabling compact representation of large numbers with fewer symbols and facilitating simpler arithmetic operations. In additive systems, values are built by repeating or combining fixed symbols without positional weighting, leading to longer notations for large quantities; positional systems, by contrast, leverage exponential growth in place values to express vast numbers succinctly.[4][6] The digit zero plays a crucial role as a placeholder in positional notation, ensuring that the positions of other digits are accurately distinguished without implying a value of zero in that place. For instance, in base 10, the numeral 10 represents ten (one ten and zero ones), whereas 1 represents only one; without zero, these could not be differentiated in a positional framework.[4][5] To visualize the place value system, consider a diagram of a numeral aligned horizontally, with positions labeled from right to left as , , , and so on, where each position holds a digit from 0 to , illustrating how the exponents denote the weighting for computation.[4] For example, in base 5, the numeral is evaluated as follows: This demonstrates the summation of place values to yield the equivalent in base 10.[5]Choice of Base

In positional notation, the base, denoted as , is defined as an integer greater than 1 that determines the number of unique digits available, ranging from 0 to .[3] This base serves as the radix, where each digit position represents a power of , enabling the compact representation of numbers through weighted place values.[3] Common bases include base 10, known as the decimal system, which uses digits 0 through 9 and is widely adopted due to the human anatomy of ten fingers facilitating counting.[7] Base 2, or binary, employs only digits 0 and 1 and forms the foundation of digital computing systems, as electronic circuits naturally operate in two states (on/off).[8] Another notable base is 60, called sexagesimal, in which digits 0-59 are represented by combinations of basic symbols (such as wedges for units and chevrons for tens), and which persists in measurements of time (60 seconds per minute, 60 minutes per hour) and angles (360 degrees per circle, subdivided into 60 arcminutes).[9][10] The choice of base influences representation efficiency: higher bases permit fewer digits to express large numbers, as each position can hold more value, but they necessitate additional symbols to accommodate the expanded digit set.[11] For instance, base 16 (hexadecimal) requires 16 symbols—digits 0-9 followed by letters A-F representing 10-15—to avoid ambiguity, ensuring all digits remain strictly less than the base value.[3] This constraint on digits (each must satisfy ) prevents overlap in place values and maintains unique numerical interpretations across positions.[3]Notation Conventions

Integer Representation

In positional notation, positive integers are represented as a finite sequence of digits read from left to right, with the leftmost digit being the most significant. For example, the decimal number 1234 consists of the digits 1, 2, 3, and 4, where each position corresponds to increasing powers of the base starting from the right.[12] This convention ensures a compact and unambiguous encoding of the integer's magnitude.[13] Unlike representations involving fractions, integer notation omits an explicit radix point, which is implicitly positioned immediately after the least significant digit at the right end. The value of such a representation is computed as the sum of each digit multiplied by the base raised to the power of its position index, starting from zero on the right. For instance, the binary representation evaluates to: This positional weighting allows efficient encoding of arbitrarily large integers by extending the digit sequence as needed.[14][15] Leading zeros in an integer's digit sequence do not alter its numerical value, as they occupy higher power positions with a zero coefficient, but they are commonly included in fixed-width formats such as computer memory allocation or display padding. For example, the binary value 000101 is equivalent to 101 and equals 5 in decimal, yet the padded form may be required for 6-bit storage.[16][17] To resolve potential ambiguity in non-decimal bases, the base is conventionally indicated by a subscript following the digit sequence, such as for a number in base . This subscript notation is essential when the context does not imply the base, particularly in mathematical or computational discussions.[18][19] Sign handling for negative integers, such as prefixing a minus symbol, follows separate conventions detailed in the section on sign and radix point.Fractional Representation

In positional notation, the fractional part of a number is represented by digits to the right of the radix point, where each position corresponds to a negative power of the base, starting with base^{-1} immediately after the point and decreasing thereafter. The value is the sum of each fractional digit multiplied by the base raised to its negative position index. For example, in decimal (base 10), the number 0.25 is interpreted as: Similarly, in binary (base 2), 0.101_2 evaluates to: Leading zeros after the radix point, such as in 0.025, do not change the value but indicate the scale of the fraction. This allows for the representation of rational numbers with finite digits if the denominator's prime factors align with the base, though some fractions require infinite or repeating expansions.[20]Sign and Radix Point

In positional notation, the sign of a number is denoted by prefixing a minus sign (−) to indicate negativity, while positivity is either unmarked or optionally prefixed with a plus sign (+). This convention allows for the representation of both positive and negative values using the same digit sequence for the magnitude, as seen in examples like −123.45 for a negative value.[21] The radix point serves to separate the integer portion from the fractional portion of a number. In contemporary usage, it is most commonly a dot (.) in English-speaking countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as in China and Japan; conversely, a comma (,) is standard in many European nations like France, Germany, and Spain, and in Latin American countries including Argentina and Mexico.[22] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO 80000-1) permits either symbol as the decimal sign, provided consistency is maintained within a document and it is placed on the baseline. Historically, before the widespread adoption of the dot or comma, a vertical bar (|) was employed as the radix point, for instance by Christoff Rudolff in 1525 and François Viète in 1579.[23] Placement conventions require the sign to precede all digits, with the radix point inserted immediately after the integer digits and before the fractional digits. Thus, in base 10, the notation −0.5 (or −0,5 in comma-using locales) denotes the value −(5 × 10^{-1}). For the number zero, +0 and −0 are mathematically equivalent, but in computing environments adhering to the IEEE 754 standard for floating-point arithmetic, −0 is a distinct representation that retains negative sign information, particularly useful in preserving the direction of underflow or in certain trigonometric functions.Historical Development

Ancient Origins

The earliest known use of positional notation emerged in ancient Mesopotamia around the early second millennium BCE, with the Babylonians developing a sexagesimal (base-60) system recorded in cuneiform script on clay tablets. This system employed wedge-shaped marks to represent digits from 1 to 59, arranged in positions that denoted powers of 60, allowing for compact representation of large numbers without a dedicated symbol for zero. However, the absence of a zero placeholder led to significant ambiguity; for instance, a single wedge could represent 1, 60, or 3600 depending on the implied position, requiring contextual interpretation from scribes.[10][24] In contrast, ancient Egyptian numerals, dating back to around 3000 BCE, relied on an additive base-10 system using hieroglyphic symbols for powers of 10 (such as a stroke for 1, a heel bone for 10, and a lotus flower for 1000), where numbers were formed by repeating and grouping these symbols without place value. This non-positional approach meant that the order of symbols did not alter their value, making calculations more laborious compared to true positional systems, though it sufficed for administrative and architectural needs.[25] By the fourth century BCE, Chinese mathematicians introduced rod numerals, a decimal positional system using bamboo or ivory rods arranged on counting boards to indicate place values, with units in the rightmost column and higher powers of 10 to the left. Empty spaces on the board served as implicit placeholders for absent digits, avoiding the need for a zero symbol while enabling efficient arithmetic operations like multiplication and division. This system persisted into the medieval period, influencing computational practices in East Asia.[26] Independently, the ancient Maya civilization in Mesoamerica developed a vigesimal (base-20) positional numeral system by around 36 BCE, using dots to represent 1, horizontal bars for 5, and a shell-shaped symbol for zero. This system, evident in early calendar inscriptions, incorporated zero as a true placeholder from its inception, enabling precise long-count calendrical and astronomical calculations that tracked time over millennia.[2] The development of a dedicated zero placeholder addressed the ambiguities inherent in earlier positional systems, with early evidence appearing in Indian Brahmi numerals by the 3rd–4th century CE, though full positional usage with zero solidified around the first century CE and was formalized by the sixth century AD. Inscriptions and texts from this era show evolving symbols where a dot or circle denoted empty positions, transforming additive precursors into a robust place-value framework that distinguished numbers like 1 from 101. The lack of zero in pre-Indian systems often necessitated additional qualifiers or spacing, highlighting a key limitation resolved through this innovation.[27][28]Evolution of Positional Fractions

In ancient Greek mathematics, fractions were primarily expressed as unit fractions, where the numerator was always 1, and more complex fractions were sums of these units, lacking a positional structure that allowed for efficient decimal-like representation.[29] This approach, inherited from Egyptian traditions, emphasized additive decompositions rather than place-value systems, limiting scalability for calculations involving arbitrary denominators.[29] Similarly, Roman fractional notation relied on additive symbols for specific portions, such as S for semis (1/2) or uncia (1/12), integrated into their non-positional numeral system, which treated fractions as discrete, word-based or symbolic addends without a unified positional framework.[30] These limitations hindered advanced arithmetic, as operations required manual summation of disparate units rather than leveraging zero-enabled place values. The integration of zero into positional systems during the Indian mathematical tradition marked a pivotal advancement for fractional representation around 628 CE, when Brahmagupta formalized arithmetic operations including zero in his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, enabling explicit notations for fractions as ratios of integers without a horizontal bar, though still separate from the integer positional line.[29] This work built on earlier Indian place-value integers by treating zero not merely as an absence but as an operational number, facilitating the conceptual bridge to decimal expansions for fractions, even if initial applications remained algorithmic rather than fully symbolic.[31] Brahmagupta's rules for addition, subtraction, and division of fractions underscored the system's potential, laying groundwork for later positional refinements by emphasizing consistency across whole and partial values.[32] During the Islamic Golden Age in the 9th century, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi refined the Hindu-Arabic positional numeral system in works like On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, incorporating zero as a placeholder and extending principles to fractional computations, which spurred systematic handling of decimals within the broader Arabic mathematical corpus.[33] This refinement, disseminated through Baghdad's scholarly networks, transformed the Indian integer-focused system into a versatile tool for astronomy and commerce, where positional decimals emerged as approximations for irrational ratios, though full decimal fraction algorithms awaited contemporaries like al-Uqlidisi around 952 CE.[34] Al-Khwarizmi's emphasis on practical computation influenced subsequent Islamic texts, standardizing zero's role in aligning fractional places with integer powers of ten.[35] The adoption of these advancements in Europe accelerated in the early 12th century through Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci, whose Liber Abaci (1202) introduced the Hindu-Arabic system, including positional principles for fractions derived from Islamic sources, to Western merchants and scholars for trade calculations.[36] Fibonacci detailed operations on fractions using verbal and symbolic methods, promoting decimal-like approximations over cumbersome Roman additives, though without a dedicated radix separator, relying instead on contextual spacing or bars for clarity.[37] This dissemination via Mediterranean commerce networks embedded positional fractions in European arithmetic, fostering gradual shifts from sexagesimal to decimal practices in accounting and navigation.[38] A key milestone in fractional notation occurred around the 1440s when Venetian merchant and astronomer Giovanni Bianchini employed a decimal point— a centered dot separating integer and fractional parts—in his astronomical tables Tabulae primi mobilis, predating previous attributions by over a century.[39] Bianchini's innovation, used for precise sine computations (e.g., 10.4 for values between 10 and 11), arose from practical needs in horoscopy and planetary modeling amid the dominant sexagesimal tradition, enhancing accuracy in decimal expansions without ambiguity.[40] This application in mercantile and scientific contexts solidified the radix point's utility, influencing later standardizations by figures like Simon Stevin in 1585 and paving the way for modern decimal notation.[41]Mathematical Properties

Base Conversion Methods

Converting numbers between different positional bases relies on algorithms that leverage the place value system, where each digit's contribution is determined by its position relative to the radix point.[42] These methods ensure accurate representation by breaking down the number into digits corresponding to powers of the target base.[43] For converting a positive integer from base 10 to base (where ), the division-remainder algorithm is used. This involves repeatedly dividing by and recording the remainders, which become the digits of the base- representation from least significant to most significant.[44] Formally, the digits satisfy , where each (with ) is the remainder when the current quotient is divided by , starting with .[45] To illustrate, consider converting 97 from base 10 to base 5:- remainder 2 (least significant digit)

- remainder 4

- remainder 3 (most significant digit)

- → digit 1, fraction 0.25

- → digit 0, fraction 0.5

- → digit 1, fraction 0.0 (terminates)

Finite and Terminating Expansions

In positional notation with base , the fractional part of a rational number (in lowest terms, with integers and ) has a terminating expansion—meaning it ends in zeros after a finite number of digits—if and only if every prime factor of is also a prime factor of .[49][50] Equivalently, there exists a positive integer such that divides .[49] For example, in base 10 (where ), the fraction terminates because the prime factor 2 of the denominator divides 10, while does not terminate (and instead repeats) since 3 is not a factor of 10.[50] More generally, in base 10, any denominator whose prime factorization consists solely of 2s and/or 5s yields a terminating expansion, such as or .[49] Integer representations in any base are always finite by definition, as they require no fractional digits and consist solely of a finite sequence of powers of up to the highest place value.[49] This termination condition can be understood through the algorithmic process of generating the expansion: to find the digits after the radix point, multiply the fractional part by repeatedly and record the integer parts. The process terminates (yielding a zero remainder) precisely when the original denominator divides some power , reducing the fraction to an integer over , or for some integer .[49] To see this formally, assume with ; the expansion is then the digits of shifted by places, finite by construction. Conversely, if the expansion terminates after digits, it equals for some integer , so must divide after clearing common factors with .[49]Infinite Series Expansions

In positional notation with base , any real number can be represented as an infinite series , where each digit is an integer satisfying . The integer part of corresponds to the finite sum over non-negative powers of , while the fractional part involves the infinite sum over negative powers, . This representation extends the finite positional system to all real numbers by allowing infinitely many digits to the right of the radix point.[51][52] The series converges absolutely for . For the fractional part, the terms satisfy , and the tail of the series is bounded by a geometric series , which approaches 0 as since . Thus, the partial sums converge to , ensuring the representation is well-defined. This convergence property holds regardless of whether the digits repeat or not, provided the base satisfies the condition.[51] Uniqueness of the representation holds except in specific terminating cases. For most real numbers, the digit sequence is unique, but numbers with a terminating expansion (ending in infinite zeros) also admit a dual representation ending in infinite 's. For example, in base 10, , and , where the infinite series . These dual forms arise precisely when the number is a finite sum of negative powers of , leading to two valid infinite series that sum to the same value.[52][51][53] A prominent example of an infinite non-terminating expansion is the base-10 representation of , which corresponds to the series with non-repeating digits continuing indefinitely without terminating or repeating. This infinite series converges to due to the base-10 geometric bound, illustrating how positional notation captures transcendental numbers through unending digit sequences.Representations of Numbers

Rational Numbers

In positional notation with integer base , every rational number has an eventually periodic expansion, meaning the digits after the radix point consist of a finite non-repeating prefix (possibly empty) followed by a repeating block of finite length.\] This property arises from the long division process, where the remainders are bounded by the denominator, leading to repetition once a remainder recurs.\[ For a reduced fraction with , the expansion is purely repeating (no non-repeating prefix) if , meaning shares no prime factors with the base ; the length of the repeating period is the multiplicative order of modulo , which divides , where is Euler's totient function.\] For example, in base 10, $1/3 = 0.\overline{3}$ has period 1, and 1 divides $\phi(3) = 2$.\[ The repeating block can be found via long division, as the sequence of remainders cycles through the multiplicative group modulo .$$] If , the expansion is mixed, with a non-repeating prefix whose length is the maximum power of any prime dividing that appears in the prime factorization of ; the repeating part then follows with period determined by the coprime portion of as above.[$$ For instance, in base 10, , where the non-repeating digit "1" corresponds to the factor of 2 (the highest power is ), and the repeating "6" has period 1 dividing .[]Irrational Numbers

In positional notation with integer base , irrational numbers possess infinite expansions that neither terminate nor become periodic, distinguishing them from rational numbers whose expansions are either finite or eventually repeating.[54] This non-periodic nature arises because any periodic or terminating expansion corresponds to a rational number, so by contrapositive, the irrationality of a number implies its expansion in base must be infinite and non-repeating.[55] For instance, the square root of 2, known to be irrational since antiquity via proof by contradiction assuming it equals in lowest terms leading to implying infinite descent in integers, has the base-10 expansion , continuing indefinitely without repetition. Similarly, the base of the natural logarithm , proven irrational by Charles Hermite in 1873 through analysis of its series expansion showing it cannot equal a rational , exhibits a non-repeating base-10 expansion ..html) These examples illustrate how irrationality ensures the digits in positional notation evade any repeating cycle, reflecting the number's transcendence beyond rational fractions. For practical representation, irrational numbers are approximated by truncating or rounding their infinite expansions to digits after the radix point, yielding an error bounded by , as the discarded tail sums to less than one unit in the th place.[56] Unlike terminating rational expansions, which admit dual representations (e.g., in base 10), irrational expansions are unique, with no alternative infinite sequence equaling the same value.[56] Positional expansions of irrationals relate to continued fraction representations, another infinite form unique to irrationals, but differ in that continued fraction convergents provide the optimal rational approximations minimizing the relative error, whereas positional truncations offer simpler but less efficient approximations.[57]Practical Applications

Decimal System Usage

The decimal system, utilizing base-10 positional notation, owes its widespread adoption to its alignment with human anatomy, particularly the ten fingers used for counting, which facilitated intuitive tallying and arithmetic in early societies.[7] This anthropomorphic basis promoted its evolution into a standard for numerical representation, with formal standardization accelerating in the late 18th century through the French Academy of Sciences' development of the metric system, which enforced decimal subdivisions for uniformity in measurements.[58] In practical applications, the decimal system underpins modern currency structures, where units like the dollar or euro are subdivided into 100 subunits (e.g., cents), enabling straightforward positional calculations for transactions and accounting.[59] It also dominates measurements via the metric system, employing powers of 10 for prefixes such as kilo- (10³) and milli- (10⁻³), which simplify conversions in length, mass, and volume.[60] Calendars, while not purely decimal, incorporate base-10 elements in date notations and durations, aligning with the system's ubiquity in daily record-keeping. A key challenge arises with fractions whose denominators include prime factors other than 2 or 5, producing non-terminating repeating decimals; for instance, 1/3 equals 0.333..., requiring rounding to approximate values in computations and potentially introducing minor errors. Such issues, detailed further in discussions of terminating expansions, underscore the need for careful precision management in base-10 representations. Standardization efforts ensure consistency, with ISO 80000-1 permitting either a point (.) or comma (,) as the radix point, though national conventions vary—many English-speaking countries use the point for decimals and comma for thousands grouping, as in 1,000.00.[61] In contrast, several European nations reverse this, employing the comma for decimals and point or space for grouping. In financial calculations, decimal places provide essential precision; for example, currency values are typically fixed at two decimal places (e.g., $12.34) to represent subunits accurately and mitigate rounding discrepancies during summations or interest computations.[59] This convention supports reliable transactional integrity across global systems.Sexagesimal and Other Historical Bases

The sexagesimal system, based on powers of 60, originated in ancient Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE among the Babylonians, who employed it extensively in mathematical and astronomical texts for its divisibility by many integers, facilitating calculations in astronomy and administration.[62] This positional notation allowed representation of large numbers and fractions, with cuneiform symbols denoting place values without a strict zero until later developments.[63] The system's influence persists in modern timekeeping, where an hour divides into 60 minutes and a minute into 60 seconds, and in angular measurement, with a circle comprising 360 degrees, each degree subdivided into 60 minutes and 60 seconds.[64] The duodecimal system, using base 12, emerged in ancient Sumerian culture around 4000 years ago, likely derived from counting the 12 phalange segments on four fingers with the thumb as a pointer, providing a highly divisible base with factors of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12.[65] This facilitated trade and measurement, as seen in the use of dozens for grouping items, and influenced timepieces with 12-hour clock faces for easy halving and thirding.[66] Remnants appear in everyday units like the 12 inches in a foot, reflecting its practicality for subdivisions in pre-metric systems.[7] In contrast, the vigesimal system of base 20 developed independently among the Maya civilization in Mesoamerica from around 2000 BCE, rooted in counting with all 20 fingers and toes for a complete set of digits represented by dots (for 1–4) and bars (for 5).[67] This positional system, including a symbol for zero, supported complex calendrical and astronomical computations, with place values scaling by 20, though sometimes modified to 18×20×20 for higher orders to align with their 360-day year.[68] While less prevalent today, traces linger in some indigenous languages and scoring terms like "score" for 20.[69] These historical bases endure in contemporary measurements due to entrenched conventions: for instance, the time 3:15 represents 3 × 60 + 15 = 195 minutes in sexagesimal notation from midnight, illustrating how Babylonian subdivisions simplify cumulative tracking without full decimal conversion.[64] Duodecimal elements aid modular divisions in commerce and navigation, while vigesimal influences appear sporadically in cultural numeracy, underscoring the adaptability of positional systems beyond the dominant decimal base.[7]Computing and Binary Systems

In computing, positional notation is predominantly implemented using base-2, known as the binary system, where each digit is either 0 or 1, referred to as a bit. This system represents numbers as sums of powers of 2, with the position of each bit determining its weight; for example, the binary number equals . Binary is fundamental to digital logic because it aligns directly with the on/off states of electronic switches, such as transistors in silicon chips, enabling efficient storage and processing of data in hardware.[70][71] Fixed-point representation extends binary positional notation to handle fractional numbers by fixing the position of the radix point (binary point) within a word of fixed length, such as an 8-bit integer where the lower bits represent fractions with an implied scaling factor. For instance, in an 8-bit fixed-point format with 4 bits for the integer part and 4 for the fractional part, the value 1010.1101_2 represents , assuming the binary point after the fourth bit. This approach is simpler and faster for arithmetic operations than floating-point, as it avoids exponent handling, making it suitable for embedded systems and digital signal processing where precision requirements are known in advance. However, it limits the dynamic range, as overflow or underflow can occur if values exceed the fixed scale.[72][73] Floating-point representation, standardized by IEEE 754, uses binary positional notation to approximate real numbers with a variable radix point, formatted as a sign bit, a biased exponent, and a mantissa (significand). In single-precision (32 bits), the format allocates 1 bit for sign, 8 bits for the biased exponent (bias of 127), and 23 bits for the mantissa, with an implied leading 1, yielding values of the form , where is the sign bit, is the mantissa fraction, and is the stored exponent. This allows a wide dynamic range, from approximately to for single-precision, essential for scientific computing and graphics. The standard ensures portability across hardware by defining rounding modes and handling special cases like infinity and NaN.[74][75] The binary system's primary advantage in digital hardware lies in its simplicity: bits correspond to two distinct voltage levels (e.g., 0V for 0 and 3.3–5V for 1), facilitating reliable implementation with basic logic gates like AND and OR, which reduces manufacturing costs and improves noise immunity since signals are unambiguous even with minor interference. Flawless data copying is another benefit, as binary transmission can filter noise without loss, supporting high-speed operations in processors. Nonetheless, challenges arise with fractional representations; for example, the decimal 0.1 has a non-terminating binary expansion , which cannot be exactly stored in finite bits, leading to approximation errors in floating-point arithmetic—such as in double-precision due to rounding in the 53-bit significand. These inaccuracies necessitate careful handling in numerical algorithms to avoid propagation.[70][71][76]Non-Standard Positional Systems

Non-standard positional systems extend the principles of traditional positional notation by employing bases or digit sets that deviate from the conventional positive integer base with digits from 0 to . These systems include fractional bases, negative bases, and redundant digit sets, each offering unique properties for representing numbers, often with advantages in compactness or computational efficiency. Such systems have been explored in mathematical literature for their theoretical interest and practical applications in areas like error detection and optimized arithmetic. Fractional bases, such as base (the golden ratio, approximately 1.618), use the irrational number as the radix, with digits restricted to 0 and 1. This system, known as the phi numeral system or phinary, allows every positive real number to be represented uniquely under the condition that no two consecutive 1s appear in the representation, avoiding the need for a sign bit and enabling efficient encoding of Fibonacci-related structures. For example, the integer 1 is represented as , while 2 is , calculated as . This base leverages the property , facilitating unique integer representations without adjacent 1s.[77][78] Negative bases, exemplified by negabinary (base -2), employ a negative integer radix with digits 0 and 1, enabling the representation of both positive and negative integers without a separate sign bit. In negabinary, the place values alternate in sign due to powers of -2: . For instance, the number 5 is represented as , computed as . This system is useful for signed number representations in computing, as it inherently accommodates negatives through the base's negativity, and has applications in error-correcting codes where balanced representations aid detection.[79][80] Redundant systems permit digit sets larger than the base, allowing multiple representations for the same number, which introduces flexibility for arithmetic operations. In a base- system, digits may range beyond 0 to , such as including values up to . This redundancy speeds up addition and multiplication by reducing carry propagation, as intermediate results can be stored without immediate normalization. Such systems find use in high-performance digital signal processing and compact coding schemes for error detection, where the extra representations enable self-checking properties.Variations and Extensions

Non-Standard Bases in Languages

In various indigenous languages, counting systems derived from body parts have led to the adoption of non-decimal bases, such as base-5 (quinary) or base-20 (vigesimal), reflecting cultural practices of tallying digits on hands and feet. For instance, many languages in Papua New Guinea employ body-tally systems where numbers are assigned to specific body parts, progressing from fingers (base-5) up one arm, across the head, and down the other arm to reach higher counts, often culminating in a vigesimal structure based on 20 digits total.[81] Similarly, the Mayan languages of Mesoamerica utilize a vigesimal system, where numerals are structured around powers of 20, a practice historians attribute to counting on all ten fingers and ten toes.[82] This body-based approach persists in modern innovations like the Kaktovik numerals developed by Iñupiaq speakers in Alaska, a base-20 positional system that visually represents values through iconic shapes tied to traditional oral counting on the body, and added to the Unicode standard in 2022 for digital support.[83][84] Modern advocacy for non-standard bases in languages includes efforts to promote base-12 (dozenal or duodecimal) systems within English-speaking contexts, arguing for its superiority in divisibility and practical applications. The Dozenal Society of America, a nonprofit organization, researches and educates on base-12 arithmetic, weights, measures, and sciences, providing resources like articles and books to facilitate its integration into everyday English usage and education.[85] Proponents highlight how base-12 aligns with cultural groupings like dozens in commerce and twelve-month calendars, positioning it as a more efficient alternative to base-10 for fractional representations in language and notation.[86] Linguistic remnants of vigesimal systems appear in Romance languages, particularly French, where numbers from 70 to 99 incorporate semi-positional elements based on multiples of 20 rather than strict decimal progression. The term quatre-vingts for 80 literally means "four twenties," a construction that deviates from pure base-10 by embedding a base-20 multiplier, influencing how speakers process and transcribe numbers.[87] This vigesimal influence, traced to Celtic and Gaulish substrates, affects cognitive tasks like number reading and calculation in French, as studies show children and adults encounter challenges in aligning these hybrid forms with decimal logic.[88] Notational innovations like Donald Knuth's up-arrow notation have subtly shaped the linguistic expression of mathematics, providing a compact way to describe hyperoperations and enormous numbers in written discourse. Introduced in 1976, the notation uses ascending arrows (e.g., ) to denote iterated exponentiation, extending beyond standard positional limits and enabling mathematicians to articulate vast scales without verbose descriptions.[89] Its adoption in academic writing has influenced how complex growth rates are verbalized and discussed, fostering a more precise "language" for theoretical computer science and number theory. Cultural persistence of base-12 elements is evident in time-related vocabulary across languages, where divisions into dozens reinforce non-decimal thinking despite dominant base-10 systems. English terms like "dozen hours" refer to the 12-hour clock cycle, a holdover from ancient Egyptian and Babylonian practices that divided the day into 12 parts based on lunar cycles and finger-joint counting (yielding 12 joints per hand excluding the thumb).[90] This duodecimal structure endures in expressions for time and measurement, such as the 12 inches in a foot or 12 months in a year, embedding base-12 logic into everyday linguistic patterns.[91]Balanced and Negabinary Systems