Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hellenistic period

View on Wikipedia| Hellenistic period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 323 – 30 BC | |||

| |||

The Winged Victory of Samothrace (The Winged Nike) is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of Hellenistic art. | |||

| Location | Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia | ||

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek and Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC,[1] which was followed by the ascendancy of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and the Roman conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt the following year, which eliminated the last major Hellenistic kingdom.[2][3] Its name stems from the Ancient Greek word Hellas (Ἑλλάς, Hellás), which was gradually recognized as the name for Greece, from which the modern historiographical term Hellenistic was derived.[4] The term "Hellenistic" is to be distinguished from "Hellenic" in that the latter refers to Greece itself, while the former encompasses all the ancient territories of the period that had come under significant Greek influence, particularly the Hellenized Ancient Near East, after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

After the Macedonian conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BC and its disintegration shortly thereafter in the Partition of Babylon and subsequent Wars of the Diadochi, Hellenistic kingdoms were established throughout West Asia (Seleucid Empire, Kingdom of Pergamon), Northeast Africa (Ptolemaic Kingdom) and South Asia (Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, Indo-Greek Kingdom).[5][6] This resulted in an influx of Greek colonists and the export of Greek culture and language to these new realms, a breadth spanning as far as modern-day India. These new Greek kingdoms were also influenced by regional indigenous cultures, adopting local practices where deemed beneficial, necessary, or convenient. Hellenistic culture thus represents a fusion of the ancient Greek world with that of the Western Asian, Northeastern African, and Southwestern Asian worlds.[7] The consequence of this mixture gave rise to a common Attic-based Greek dialect, known as Koine Greek, which became the lingua franca throughout the ancient world.

During the Hellenistic period, Greek cultural influence reached its peak in the Mediterranean and beyond. Prosperity and progress in the arts, literature, theatre, architecture, music, mathematics, philosophy, and science characterize the era. The Hellenistic period saw the rise of New Comedy, Alexandrian poetry, translation efforts such as the Septuagint, and the philosophies of Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Pyrrhonism. In science, the works of the mathematician Euclid and the polymath Archimedes are exemplary. Sculpture during this period was characterized by intense emotion and dynamic movement, as seen in sculptural works like the Dying Gaul and the Venus de Milo. A form of Hellenistic architecture arose which especially emphasized the building of grand monuments and ornate decorations, as exemplified by structures such as the Pergamon Altar. The religious sphere of Greek religion expanded through syncretic facets to include new gods such as the Greco-Egyptian Serapis, eastern deities such as Attis and Cybele, and a syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism in Bactria and Northwest India.

Scholars and historians are divided as to which event signals the end of the Hellenistic era. There is a wide chronological range of proposed dates that have included the final conquest of the Greek heartlands by the expansionist Roman Republic in 146 BC following the Achaean War, the final defeat of the Ptolemaic Kingdom at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, the end of the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian in AD 138,[8] and the move by the emperor Constantine the Great of the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople in AD 330.[3][9] Though this scope of suggested dates demonstrates a range of academic opinion, a generally accepted date by most of scholarship has been that of 31/30 BC.[10][11][12]

Etymology

[edit]The word originated from Ancient Greek Ἑλληνιστής (Hellēnistḗs, "one who uses the Greek language"), from Ἑλλάς (Hellás, "Greece"); as if "Hellenist" + "ic".[13]

Right image: painted clay and alabaster head of a Zoroastrian priest wearing a distinctive Bactrian-style headdress, Takhti-Sangin, Tajikistan, 3rd–2nd century BC

The idea of a Hellenistic period is a 19th-century concept, and did not exist in ancient Greece. Although words related in form or meaning, e.g. Hellenist (Ancient Greek: Ἑλληνιστής, Hellēnistēs), have been attested since ancient times,[14] it has been attributed to the 19th-century German historian Johann Gustav Droysen, who in his classic work Geschichte des Hellenismus (History of Hellenism), coined the term Hellenistic to refer to and define the period when Greek culture spread in the non-Greek world after Alexander's conquest.[15] Following Droysen, Hellenistic and related terms, e.g. Hellenism, have been widely used in various contexts; a notable such use is in Culture and Anarchy by Matthew Arnold, where Hellenism is used in contrast with Hebraism.[16][17]

The major issue with the term Hellenistic lies in its convenience, as the spread of Greek culture was not the generalized phenomenon that the term implies. Some areas of the conquered world were more affected by Greek influences than others. The term Hellenistic also implies that the Greek populations were of majority in the areas in which they settled, but in many cases, the Greek settlers were actually the minority among the native populations. The Greek population and the native population did not always mix; the Greeks moved and brought their own culture, but interaction did not always occur.[citation needed]

Sources

[edit]

Literary works

[edit]While a few fragments exist, there are no complete surviving historical works that date to the hundred years following Alexander's death. The works of the major Hellenistic historians Hieronymus of Cardia (who worked under Alexander, Antigonus I and other successors), Duris of Samos and Phylarchus, which were used by surviving sources, are all lost.[19] The earliest and most credible surviving source for the Hellenistic period is Polybius of Megalopolis (c. 200–118), a statesman of the Achaean League until 168 BC when he was forced to go to Rome as a hostage.[19] His Histories eventually grew to a length of forty books, covering the years 220 to 167 BC.

The most important source after Polybius is Diodorus Siculus who wrote his Bibliotheca historica between 60 and 30 BC and reproduced some important earlier sources such as Hieronymus, but his account of the Hellenistic period breaks off after the battle of Ipsus (301 BC). Another important source, Plutarch's (c. AD 50 – c. 120) Parallel Lives although more preoccupied with issues of personal character and morality, outlines the history of important Hellenistic figures. Appian of Alexandria (late 1st century AD–before 165) wrote a history of the Roman Empire that includes information of some Hellenistic kingdoms.[citation needed]

Other sources include Justin's (2nd century AD) epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Historiae Philipicae and a summary of Arrian's Events after Alexander, by Photios I of Constantinople. Lesser supplementary sources include Curtius Rufus, Pausanias, Pliny, and the Byzantine encyclopedia the Suda. In the field of philosophy, Diogenes Laërtius' Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is the main source; works such as Cicero's De Natura Deorum also provide some further detail of philosophical schools in the Hellenistic period.[citation needed]

Inscriptions

[edit]

Inscriptions on stone or metal were commonly erected throughout the Greek world for public display, a practice which originated well before the time of Alexander the Great, but saw substantial expansion during the Hellenistic Period. The majority of these inscriptions are located on the Greek mainland, the Greek islands, and western Asia Minor. While they become increasingly rare towards the eastern regions, they are not entirely absent there, and they are most notably featured in public buildings and sanctuaries. The content of these inscriptions is diverse, encompassing royal correspondence addressed to cities or individuals, municipal and legal edicts, decrees commemorating rulers, officials, and individuals for their contributions, as well as laws, treaties, religious rulings, and dedications. Despite challenges in their interpretation, inscriptions are often the only source available for understanding numerous events in Greek history.[20]p:7-8

Papyri

[edit]Papyrus served as the predominant medium for handwritten documents across the Hellenistic world, though its production was confined to Egypt. Due to Egypt's arid climate, papyrus manuscripts were almost exclusively preserved there as well. That being said, the different historical periods are not represented equally in the papyrological documents. Texts from the reign of Ptolemy I are notably scarce, while those from the reign of Ptolemy II are more frequently encountered, this is owing in part to the large quantities of papyri which were stuffed into human and animal mummies during his rule. Papyri have been classified into public and private documents, including literary texts, laws and regulations, official correspondence, petitions, records, and archives or collections of documents belonging to individuals of position and authority. Significant information about the Ptolemaic Kingdom, which might otherwise have been lost, has been preserved in papyrological documents. This is particularly noteworthy given the limited documentation available for their Seleucid counterparts.[20]p:8-9

Background

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early rule

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Expedition into India

Death and legacy

Cultural impact

|

||

Ancient Greece was a patchwork of independent city-states and kingdoms. After the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), Sparta held a hegemony that was later displaced by Thebes following the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC). The indecisive outcome at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC) left the Greek world fragmented, creating conditions in which the northern Greek kingdom of Macedon rose to predominance under king Philip II. Macedon lay on the geographical periphery of the Greek world. Some contemporaries in the southern poleis disparaged it as less urbanised, although the royal Argead dynasty traced Greek descent. The kingdom controlled a large territory and possessed a comparatively strong centralised monarchy, unlike most poleis.[21]

Philip II pursued expansion wherever opportunity allowed. In 352 BC he annexed Thessaly and Magnesia. In 338 BC he defeated a combined Theban and Athenian army at the Battle of Chaeronea after a decade of intermittent conflict. In the aftermath Philip formed the League of Corinth, bringing most of Greece under his leadership. He was elected Hegemon of the League, and a campaign against the Achaemenid Empire was planned. In 336 BC, while preparations were under way, he was assassinated.[22]

Succeeding his father, Alexander took command of the Persian war. Over a decade of campaigning he overthrew the Achaemenid Empire and the king Darius III. The conquered lands included Asia Minor, Assyria, the Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Media, Persia, and parts of modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the central Asian steppes. The strain of continuous campaigning was severe, and Alexander died in 323 BC.

After his death, the territories he had conquered experienced sustained Greek cultural influence (Hellenisation) for the next two or three centuries, until the rise of the Roman Empire in the west and the Parthian Empire in the east. As Greek and Levantine cultures interacted, a hybrid Hellenistic culture developed and persisted even when far from the principal Greek centres, for example in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom.

Scholars note that not all changes across the former empire can be attributed solely to Greek rule. As Peter Green observes, diverse phenomena of conquest are often grouped under the term Hellenistic period. In several regions, including Egypt and parts of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, Alexander was sometimes received as a liberator rather than as a mere conqueror.[23]

In the subsequent era, much of the area continued under the Diadochi, Alexander’s generals and successors. The empire was initially divided among them, though some territories were quickly lost or only nominally acknowledged Macedonian authority. After about two centuries, the remaining successor states were much reduced, culminating in the Roman conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt.[9]

The Diadochi

[edit]

When Alexander the Great died (10 June 323 BC), he left behind a sprawling empire that was composed of many essentially autonomous territories called satrapies. Without a chosen successor, there were immediate disputes among his generals as to who should be king of Macedon. These generals became known as the Diadochi (Ancient Greek: Διάδοχοι, Diadokhoi, meaning "Successors").

Meleager and the infantry supported the candidacy of Alexander's half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, while Perdiccas, the leading cavalry commander, supported waiting until the birth of Alexander's child by Roxana. After the infantry stormed the palace of Babylon, a compromise was arranged – Arrhidaeus (as Philip III) should become king and should rule jointly with Roxana's child, assuming that it was a boy (as it was, becoming Alexander IV). Perdiccas himself would become regent (epimeletes) of the empire, and Meleager his lieutenant. Soon, however, Perdiccas had Meleager and the other infantry leaders murdered and assumed full control.[24] The generals who had supported Perdiccas were rewarded in the partition of Babylon by becoming satraps of the various parts of the empire, but Perdiccas' position was shaky because, as Arrian writes, "everyone was suspicious of him, and he of them".[25]

The first of the Diadochi wars broke out when Perdiccas planned to marry Alexander's sister Cleopatra and began to question Antigonus I Monophthalmus' leadership in Asia Minor. Antigonus fled for Greece, and then, together with Antipater and Craterus (the satrap of Cilicia who had been in Greece fighting the Lamian war) invaded Anatolia. The rebels were supported by Lysimachus, the satrap of Thrace and Ptolemy, the satrap of Egypt. Although Eumenes, satrap of Cappadocia, defeated the rebels in Asia Minor, Perdiccas himself was murdered by his own generals Peithon, Seleucus, and Antigenes (possibly with Ptolemy's aid) during his invasion of Egypt (c. 21 May to 19 June, 320 BC).[26] Ptolemy came to terms with Perdiccas's murderers, making Peithon and Arrhidaeus regents in his place, but soon these came to a new agreement with Antipater at the Treaty of Triparadisus. Antipater was made regent of the Empire, and the two kings were moved to Macedon. Antigonus remained in charge of Asia Minor, Ptolemy retained Egypt, Lysimachus retained Thrace and Seleucus I controlled Babylon.

The second Diadochi war began following the death of Antipater in 319 BC. Passing over his own son, Cassander, Antipater had declared Polyperchon his successor as Regent.[27] Cassander rose in revolt against Polyperchon (who was joined by Eumenes) and was supported by Antigonus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy. In 317 BC, Cassander invaded Macedonia, attaining control of Macedon, sentencing Olympias to death and capturing the boy king Alexander IV, and his mother. In Asia, Eumenes was betrayed by his own men after years of campaign and was given up to Antigonus who had him executed.

The third war of the Diadochi broke out because of the growing power and ambition of Antigonus. He began removing and appointing satraps as if he were king and also raided the royal treasuries in Ecbatana, Persepolis and Susa, making off with 25,000 talents.[28] Seleucus was forced to flee to Egypt and Antigonus was soon at war with Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander. He then invaded Phoenicia, laid siege to Tyre, stormed Gaza and began building a fleet. Ptolemy invaded Syria and defeated Antigonus' son, Demetrius Poliorcetes, in the Battle of Gaza of 312 BC which allowed Seleucus to secure control of Babylonia, and the eastern satrapies. In 310 BC, Cassander had young King Alexander IV and his mother Roxana murdered, ending the Argead dynasty which had ruled Macedon for several centuries.

Antigonus then sent his son Demetrius to regain control of Greece. In 307 BC he took Athens, expelling Demetrius of Phaleron, Cassander's governor, and proclaiming the city free again. Demetrius now turned his attention to Ptolemy, defeating his fleet at the Battle of Salamis and taking control of Cyprus.[27] In the aftermath of this victory, Antigonus took the title of king (basileus) and bestowed it on his son Demetrius Poliorcetes, the rest of the Diadochi soon followed suit.[29] Demetrius continued his campaigns by laying siege to Rhodes and conquering most of Greece in 302 BC, creating a league against Cassander's Macedon.

The decisive engagement of the war came when Lysimachus invaded and overran much of western Anatolia, but was soon isolated by Antigonus and Demetrius near Ipsus in Phrygia. Seleucus arrived in time to save Lysimachus and utterly crushed Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. Seleucus' war elephants proved decisive; Antigonus was killed, and Demetrius fled back to Greece to attempt to preserve the remnants of his rule, thereby recapturing a rebellious Athens. Meanwhile, Lysimachus took over Ionia, Seleucus took Cilicia, and Ptolemy captured Cyprus.

After Cassander's death in c. 298 BC, however, Demetrius, who still maintained a sizable loyal army and fleet, invaded Macedon, seized the Macedonian throne (294 BC) and conquered Thessaly and most of central Greece (293–291 BC).[30] He was defeated in 288 BC when Lysimachus of Thrace and Pyrrhus of Epirus invaded Macedon on two fronts, and quickly carved up the kingdom for themselves. Demetrius fled to central Greece with his mercenaries and began to build support there and in the northern Peloponnese. He once again laid siege to Athens after they turned on him, but then struck a treaty with the Athenians and Ptolemy, which allowed him to cross over to Asia Minor and wage war on Lysimachus' holdings in Ionia, leaving his son Antigonus Gonatas in Greece. After initial successes, he was forced to surrender to Seleucus in 285 BC and later died in captivity.[31] Lysimachus, who had seized Macedon and Thessaly for himself, was forced into war when Seleucus invaded his territories in Asia Minor and was defeated and killed in 281 BC at the Battle of Corupedium, near Sardis. Seleucus then attempted to conquer Lysimachus' European territories in Thrace and Macedon, but he was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus ("the thunderbolt"), who had taken refuge at the Seleucid court and then had himself acclaimed as king of Macedon. Ptolemy was killed when Macedon was invaded by Gauls in 279 BC—his head stuck on a spear—and the country fell into anarchy. Antigonus II Gonatas invaded Thrace in the summer of 277 and defeated a large force of 18,000 Gauls. He was quickly hailed as king of Macedon and went on to rule for 35 years.[32]

At this point the tripartite territorial division of the Hellenistic age was in place, with the main Hellenistic powers being Macedon under Demetrius's son Antigonus II Gonatas, the Ptolemaic kingdom under Ptolemy's son Ptolemy II and the Seleucid empire under Seleucus' son Antiochus I Soter.

Southern Europe

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Kingdom of Epirus

[edit]Epirus was a northwestern Greek kingdom in the western Balkans ruled by the Molossian Aeacidae dynasty. Epirus was an ally of Macedon during the reigns of Philip II and Alexander.

In 281 Pyrrhus (nicknamed "the eagle", aetos) invaded southern Italy to aid the city state of Tarentum. Pyrrhus defeated the Romans in the Battle of Heraclea and at the Battle of Asculum. Though victorious, he was forced to retreat due to heavy losses, hence the term "Pyrrhic victory". Pyrrhus then turned south and invaded Sicily but was unsuccessful and returned to Italy. After the Battle of Beneventum (275 BC) Pyrrhus lost all his Italian holdings and left for Epirus.

Pyrrhus then went to war with Macedonia in 275 BC, deposing Antigonus II Gonatas and briefly ruling over Macedonia and Thessaly until 272. Afterwards, he invaded southern Greece and was killed in battle against Argos in 272 BC. After the death of Pyrrhus, Epirus remained a minor power. In 233 BC the Aeacid royal family was deposed and a federal state was set up called the Epirote League. The league was conquered by Rome in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).

Kingdom of Macedon

[edit]

Antigonus II, a student of Zeno of Citium, spent most of his rule defending Macedon against Epirus and cementing Macedonian power in Greece, first against the Athenians in the Chremonidean War, and then against the Achaean League of Aratus of Sicyon. Under the Antigonids, Macedonia was often short on funds, the Pangaeum mines were no longer as productive as under Philip II, the wealth from Alexander's campaigns had been used up and the countryside pillaged by the Gallic invasion.[33] A large number of the Macedonian population had also been resettled abroad by Alexander or had chosen to emigrate to the new eastern Greek cities. Up to two-thirds of the population emigrated, and the Macedonian army could only count on a levy of 25,000 men, a significantly smaller force than under Philip II.[34]

Antigonus II ruled until his death in 239 BC. His son Demetrius II soon died in 229 BC, leaving a child (Philip V) as king, with the general Antigonus Doson as regent. Doson led Macedon to victory in the war against the Spartan king Cleomenes III, and occupied Sparta.

Philip V, who came to power when Doson died in 221 BC, was the last Macedonian ruler with both the talent and the opportunity to unite Greece and preserve its independence against the "cloud rising in the west": the ever-increasing power of Rome. He was known as "the darling of Hellas". Under his auspices the Peace of Naupactus (217 BC) brought the latest war between Macedon and the Greek leagues (the Social War of 220–217 BC) to an end, and at this time he controlled all of Greece except Athens, Rhodes and Pergamum.

In 215 BC Philip, with his eye on Illyria, formed an alliance with Rome's enemy Hannibal of Carthage, which led to Roman alliances with the Achaean League, Rhodes and Pergamum. The First Macedonian War broke out in 212 BC, and ended inconclusively in 205 BC. Philip continued to wage war against Pergamum and Rhodes for control of the Aegean (204–200 BC) and ignored Roman demands for non-intervention in Greece by invading Attica. In 198 BC, during the Second Macedonian War Philip was decisively defeated at Cynoscephalae by the Roman proconsul Titus Quinctius Flamininus and Macedon lost all its territories in Greece proper. Southern Greece was now thoroughly brought into the Roman sphere of influence, though it retained nominal autonomy. The end of Antigonid Macedon came when Philip V's son, Perseus, was defeated and captured by the Romans in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).

Rest of Greece

[edit]

During the Hellenistic period, the importance of Greece proper within the Greek-speaking world declined sharply. The great centers of Hellenistic culture were Alexandria and Antioch, capitals of Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria respectively. The conquests of Alexander greatly widened the horizons of the Greek world, making the endless conflicts between the cities that had marked the 5th and 4th centuries BC seem petty and unimportant. It led to a steady emigration, particularly of the young and ambitious, to the new Greek empires in the east. Many Greeks migrated to Alexandria, Antioch, and the many other new Hellenistic cities founded in Alexander's wake, as far away as modern Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Independent city states were unable to compete with Hellenistic kingdoms and were usually forced to ally themselves to one of them for defense, giving honors to Hellenistic rulers in return for protection. One example is Athens, which had been decisively defeated by Antipater in the Lamian war (323–322 BC) and had its port in the Piraeus garrisoned by Macedonian troops who supported a conservative oligarchy.[35] After Demetrius Poliorcetes captured Athens in 307 BC and restored the democracy, the Athenians honored him and his father Antigonus by placing gold statues of them on the agora and granting them the title of king. Athens later allied itself to Ptolemaic Egypt to throw off Macedonian rule, eventually setting up a religious cult for the Ptolemaic kings and naming one of the city's phyles in honour of Ptolemy for his aid against Macedon. In spite of the Ptolemaic monies and fleets backing their endeavors, Athens and Sparta were defeated by Antigonus II during the Chremonidean War (267–261 BC). Athens was then occupied by Macedonian troops, and run by Macedonian officials.

Sparta remained independent, but it was no longer the leading military power in the Peloponnese. The Spartan king Cleomenes III (235–222 BC) staged a military coup against the conservative ephors and pushed through radical social and land reforms in order to increase the size of the shrinking Spartan citizenry able to provide military service and restore Spartan power. Sparta's bid for supremacy was crushed at the Battle of Sellasia (222 BC) by the Achaean league and Macedon, who restored the power of the ephors.

Other city states formed federated states in self-defense, such as the Aetolian League (est. 370 BC), the Achaean League (est. 280 BC), the Boeotian league, the "Northern League" (Byzantium, Chalcedon, Heraclea Pontica and Tium)[36] and the "Nesiotic League" of the Cyclades. These federations involved a central government which controlled foreign policy and military affairs, while leaving most of the local governing to the city states, a system termed sympoliteia. In states such as the Achaean league, this also involved the admission of other ethnic groups into the federation with equal rights, in this case, non-Achaeans.[37] The Achean league was able to drive out the Macedonians from the Peloponnese and free Corinth, which duly joined the league.

One of the few city states who managed to maintain full independence from the control of any Hellenistic kingdom was Rhodes. With a skilled navy to protect its trade fleets from pirates and an ideal strategic position covering the routes from the east into the Aegean, Rhodes prospered during the Hellenistic period. It became a center of culture and commerce, its coins were widely circulated and its philosophical schools became one of the best in the Mediterranean. After holding out for one year under siege by Demetrius Poliorcetes (305–304 BC), the Rhodians built the Colossus of Rhodes to commemorate their victory. They retained their independence by the maintenance of a powerful navy, by maintaining a carefully neutral posture and acting to preserve the balance of power between the major Hellenistic kingdoms.[38]

Initially, Rhodes had very close ties with the Ptolemaic kingdom. Rhodes later became a Roman ally against the Seleucids, receiving some territory in Caria for their role in the Roman–Seleucid War (192–188 BC).

Balkans

[edit]

The west Balkan coast was inhabited by various Illyrian tribes and kingdoms such as the kingdom of the Dalmatae and of the Ardiaei, who often engaged in piracy under Queen Teuta (reigned 231–227 BC). Further inland was the Illyrian Paeonian Kingdom and the tribe of the Agrianes. Illyrians on the coast of the Adriatic were under the effects and influence of Hellenisation and some tribes adopted Greek, becoming bilingual[39][40][41] due to their proximity to the Greek colonies in Illyria. Illyrians imported weapons and armor from the ancient Greeks (such as the Illyrian type helmet, originally a Greek type) and also adopted the ornamentation of ancient Macedon on their shields[42] and their war belts[43] (a single one has been found, dated 3rd century BC at modern Selcë e Poshtme, a part of Macedon at the time under Philip V of Macedon[44]).

The Odrysian Kingdom was a union of Thracian tribes under the kings of the powerful Odrysian tribe. Various parts of Thrace were under Macedonian rule under Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great, Lysimachus, Ptolemy II, and Philip V but were also often ruled by their own kings. The Thracians and Agrianes were widely used by Alexander as peltasts and light cavalry, forming about one-fifth of his army.[45] The Diadochi also used Thracian mercenaries in their armies and they were also used as colonists. The Odrysians used Greek as the language of administration[46] and of the nobility. The nobility also adopted Greek fashions in dress, ornament, and military equipment, spreading it to the other tribes.[47] Thracian kings were among the first to be Hellenized.[48]

After 278 BC the Odrysians had a strong competitor in the Celtic Kingdom of Tylis ruled by the kings Comontorius and Cavarus, but in 212 BC they conquered their enemies and destroyed their capital.

Western Mediterranean

[edit]

Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) and south-eastern Sicily had been colonized by the Greeks during the 8th century BC. In 4th-century BC Sicily the leading Greek city and hegemon was Syracuse. During the Hellenistic period the leading figure in Sicily was Agathocles of Syracuse (361–289 BC) who seized the city with an army of mercenaries in 317 BC. Agathocles extended his power throughout most of the Greek cities in Sicily, fought a long war with the Carthaginians, at one point invading Tunisia in 310 BC and defeating a Carthaginian army there. This was the first time a European force had invaded the region. After this war he controlled most of south-east Sicily and had himself proclaimed king, in imitation of the Hellenistic monarchs of the east.[49] Agathocles then invaded Italy (c. 300 BC) in defense of Tarentum against the Bruttians and Romans, but was unsuccessful.

Greeks in pre-Roman Gaul were mostly limited to the Mediterranean coast of Provence, France. The first Greek colony in the region was Massalia, which became one of the largest trading ports of Mediterranean by the 4th century BC with 6,000 inhabitants. Massalia was also the local hegemon, controlling various coastal Greek cities like Nice and Agde. The coins minted in Massalia have been found in all parts of Liguro-Celtic Gaul. Celtic coinage was influenced by Greek designs,[50] and Greek letters can be found on various Celtic coins, especially those of Southern France.[51] Traders from Massalia ventured inland deep into France on the Rivers Durance and Rhône, and established overland trade routes deep into Gaul, and to Switzerland and Burgundy. The Hellenistic period saw the Greek alphabet spread into southern Gaul from Massalia (3rd and 2nd centuries BC) and according to Strabo, Massalia was also a center of education, where Celts went to learn Greek.[52] A staunch ally of Rome, Massalia retained its independence until it sided with Pompey in 49 BC and was then taken by Caesar's forces.

The city of Emporion (modern Empúries), originally founded by Archaic-period settlers from Phocaea and Massalia in the 6th century BC near the village of Sant Martí d'Empúries (located on an offshore island that forms part of L'Escala, Catalonia, Spain),[53] was reestablished in the 5th century BC with a new city (neapolis) on the Iberian mainland.[54] Emporion contained a mixed population of Greek colonists and Iberian natives, and although Livy and Strabo assert that they lived in different quarters, these two groups were eventually integrated.[55] The city became a dominant trading hub and center of Hellenistic civilization in Iberia, eventually siding with the Roman Republic against the Carthaginian Empire during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC).[56] However, Emporion lost its political independence around 195 BC with the establishment of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior and by the 1st century BC had become fully Romanized in culture.[57][58]

Hellenistic Near East

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

The Hellenistic states of Asia and Egypt were run by an occupying imperial elite of Greco-Macedonian administrators and governors propped up by a standing army of mercenaries and a small core of Greco-Macedonian settlers.[59] Promotion of immigration from Greece was important in the establishment of this system. Hellenistic monarchs ran their kingdoms as royal estates and most of the heavy tax revenues went into the military and paramilitary forces which preserved their rule from any kind of revolution. Macedonian and Hellenistic monarchs were expected to lead their armies on the field, along with a group of privileged aristocratic companions or friends (hetairoi, philoi) which dined and drank with the king and acted as his advisory council.[60] The monarch was also expected to serve as a charitable patron of the people; this public philanthropy could mean building projects and handing out gifts but also promotion of Greek culture and religion.

Ptolemaic Kingdom

[edit]Ptolemy, a somatophylax, one of the seven bodyguards who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (saviour) for his role in helping the Rhodians during the siege of Rhodes. Ptolemy built new cities such as Ptolemais Hermiou in upper Egypt and settled his veterans throughout the country, especially in the region of the Faiyum. Alexandria, a major center of Greek culture and trade, became his capital city. As Egypt's first port city, it became the main grain exporter in the Mediterranean.

The Egyptians begrudgingly accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt, though the kingdom went through several native revolts. Ptolemy I began to order monetary contributions from the people and, as a result, rewarded cities with high contributions with royal benefaction. This often resulted in the formation of a royal cult within the city. Reservations about this activity slowly dissipated as this worship of mortals was justified by the precedent of the worshipping of Greek heroes.[61] The Ptolemies took on the traditions of the Egyptian Pharaohs, such as marrying their siblings (Ptolemy II was the first to adopt this custom), having themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participating in Egyptian religious life. The Ptolemaic ruler cult portrayed the Ptolemies as gods, and temples to the Ptolemies were erected throughout the kingdom. Ptolemy I even created a new god, Serapis, who was a combination of two Egyptian gods: Apis and Osiris, with attributes of Greek gods. Ptolemaic administration was, like the ancient Egyptian bureaucracy, highly centralized and focused on squeezing as much revenue out of the population as possible through tariffs, excise duties, fines, taxes, and so forth. A whole class of petty officials, tax farmers, clerks, and overseers made this possible. The Egyptian countryside was directly administered by this royal bureaucracy.[62] External possessions such as Cyprus and Cyrene were run by strategoi, military commanders appointed by the crown.

Under Ptolemy II, Callimachus, Apollonius of Rhodes, Theocritus, and a host of other poets including the Alexandrian Pleiad made the city a center of Hellenistic literature. Ptolemy himself was eager to patronise the library, scientific research and individual scholars who lived on the grounds of the library. He and his successors also fought a series of wars with the Seleucids, known as the Syrian wars, over the region of Coele-Syria. Ptolemy IV won the great battle of Raphia (217 BC) against the Seleucids, using native Egyptians trained as phalangites. However these Egyptian soldiers revolted, eventually setting up a native breakaway Egyptian state in the Thebaid between 205 and 186/185 BC, severely weakening the Ptolemaic state.[63]

Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe, or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt, though Hellenistic culture continued to thrive in Egypt throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods until the Muslim conquest.

Seleucid Empire

[edit]

Following division of Alexander's empire, Seleucus I Nicator received Babylonia. From there, he created a new empire which expanded to include much of Alexander's Near Eastern territories.[64][65][66][67] At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, today's Turkmenistan, Pamir, and parts of Pakistan. It included a diverse population estimated at fifty to sixty million people.[68] Under Antiochus I (c. 324/323 – 261 BC), however, the unwieldy empire was already beginning to shed territories. Pergamum broke away under Eumenes I who defeated a Seleucid army sent against him. The kingdoms of Cappadocia, Bithynia and Pontus were all practically independent by this time as well. Like the Ptolemies, Antiochus I established a dynastic religious cult, deifying his father Seleucus I. Seleucus, officially said to be descended from Apollo, had his own priests and monthly sacrifices. The erosion of the empire continued under Seleucus II, who was forced to fight a civil war (239–236 BC) against his brother Antiochus Hierax and was unable to keep Bactria, Sogdiana and Parthia from breaking away. Hierax carved off most of Seleucid Anatolia for himself, but was defeated, along with his Galatian allies, by Attalus I of Pergamon who now also claimed kingship.

The vast Seleucid Empire was, like Egypt, mostly dominated by a Greco-Macedonian political elite.[67][69][70][71] The Greek population of the cities who formed the dominant elite were reinforced by emigration from Greece.[67][69] These cities included newly founded colonies such as Antioch, the other cities of the Syrian tetrapolis, Seleucia (north of Babylon) and Dura-Europos on the Euphrates. These cities retained traditional Greek city state institutions such as assemblies, councils and elected magistrates, but this was a facade for they were always controlled by the royal Seleucid officials. Apart from these cities, there were also a large number of Seleucid garrisons (choria), military colonies (katoikiai) and Greek villages (komai) which the Seleucids planted throughout the empire to cement their rule. This 'Greco-Macedonian' population (which also included the sons of settlers who had married local women) could make up a phalanx of 35,000 men (out of a total Seleucid army of 80,000) during the reign of Antiochus III. The rest of the army was made up of native troops.[72] Antiochus III ("the Great") conducted several vigorous campaigns to retake all the lost provinces of the empire since the death of Seleucus I. After being defeated by Ptolemy IV's forces at Raphia (217 BC), Antiochus III led a long campaign to the east to subdue the far eastern breakaway provinces (212–205 BC) including Bactria, Parthia, Ariana, Sogdiana, Gedrosia and Drangiana. He was successful, bringing back most of these provinces into at least nominal vassalage and receiving tribute from their rulers.[73] After the death of Ptolemy IV (204 BC), Antiochus took advantage of the weakness of Egypt to conquer Coele-Syria in the fifth Syrian war (202–195 BC).[74] He then began expanding his influence into Pergamene territory in Asia and crossed into Europe, fortifying Lysimachia on the Hellespont, but his expansion into Anatolia and Greece was abruptly halted after a decisive defeat at the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC). In the Treaty of Apamea which ended the war, Antiochus lost all of his territories in Anatolia west of the Taurus and was forced to pay a large indemnity of 15,000 talents.[75]

Much of the eastern part of the empire was then conquered by the Parthians under Mithridates I of Parthia in the mid-2nd century BC, yet the Seleucid kings continued to rule a rump state from Syria until the invasion by the Armenian king Tigranes the Great and their ultimate overthrow by the Roman general Pompey.

Attalid Pergamum

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

After the death of Lysimachus, one of his officers, Philetaerus, took control of the city of Pergamum in 282 BC along with Lysimachus' war chest of 9,000 talents and declared himself loyal to Seleucus I while remaining de facto independent. His descendant, Attalus I, defeated the invading Galatians and proclaimed himself an independent king. Attalus I (241–197 BC), was a staunch ally of Rome against Philip V of Macedon during the first and second Macedonian Wars. For his support against the Seleucids in 190 BC, Eumenes II was rewarded with all the former Seleucid domains in Asia Minor. Eumenes II turned Pergamon into a centre of culture and science by establishing the Library of Pergamum which was said to be second only to the Library of Alexandria[77] with 200,000 volumes according to Plutarch. It included a reading room and a collection of paintings. Eumenes II also constructed the Pergamum Altar with friezes depicting the Gigantomachy on the acropolis of the city. Pergamum was also a center of parchment (charta pergamena) production. The Attalids ruled Pergamon until Attalus III bequeathed the Kingdom of Pergamon to the Roman Republic in 133 BC[78] to avoid a likely succession crisis.

Galatia

[edit]The Celts who settled in Galatia came through Thrace under the leadership of Leotarios and Leonnorios c. 270 BC. They were defeated by Seleucus I in the 'battle of the Elephants', but were still able to establish a Celtic territory in central Anatolia. The Galatians were well respected as warriors and were widely used as mercenaries in the armies of the successor states. They continued to attack neighboring kingdoms such as Bithynia and Pergamon, plundering and extracting tribute. This came to an end when they sided with the renegade Seleucid prince Antiochus Hierax who tried to defeat Attalus, the ruler of Pergamon (241–197 BC). Attalus severely defeated the Gauls, forcing them to confine themselves to Galatia. The theme of the Dying Gaul (a famous statue displayed in Pergamon) remained a favorite in Hellenistic art for a generation signifying the victory of the Greeks over a noble enemy. In the early 2nd century BC, the Galatians became allies of Antiochus the Great, the last Seleucid king trying to regain suzerainty over Asia Minor. In 189 BC, Rome sent Gnaeus Manlius Vulso on an expedition against the Galatians. Galatia was henceforth dominated by Rome through regional rulers from 189 BC onward.

After their defeats by Pergamon and Rome the Galatians slowly became Hellenized and they were called "Gallo-Graeci" by the historian Justin[79] as well as Ἑλληνογαλάται (Hellēnogalátai) by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica v.32.5, who wrote that they were "called Helleno-Galatians because of their connection with the Greeks."[80]

Bithynia

[edit]

The Bithynians were a Thracian people living in northwest Anatolia. After Alexander's conquests the region of Bithynia came under the rule of the native king Bas, who defeated Calas, a general of Alexander the Great, and maintained the independence of Bithynia. His son, Zipoetes I of Bithynia maintained this autonomy against Lysimachus and Seleucus I, and assumed the title of king (basileus) in 297 BC. His son and successor, Nicomedes I, founded Nicomedia, which soon rose to great prosperity, and during his long reign (c. 278 – c. 255 BC), as well as those of his successors, the Kingdom of Bithynia held a considerable place among the minor monarchies of Anatolia. Nicomedes also invited the Celtic Galatians into Anatolia as mercenaries, and they later turned on his son Prusias I, who defeated them in battle. Their last king, Nicomedes IV, was unable to maintain himself against Mithridates VI of Pontus, and, after being restored to his throne by the Roman Senate, he bequeathed his kingdom by will to the Roman Republic (74 BC).

Nabatean Kingdom

[edit]

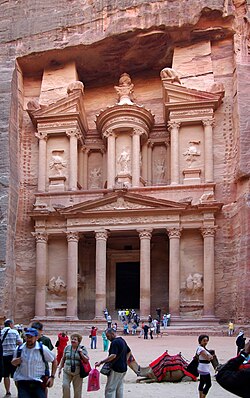

The Nabatean Kingdom was an Arab state located between the Sinai Peninsula and the Arabian Peninsula. Its capital was the city of Petra, an important trading city on the incense route. The Nabateans resisted the attacks of Antigonus and were allies of the Hasmoneans in their struggle against the Seleucids, but later fought against Herod the Great. The hellenization of the Nabateans occurred relatively late in comparison to the surrounding regions. Nabatean material culture does not show any Greek influence until the reign of Aretas III Philhellene in the 1st century BC.[81] Aretas captured Damascus and built the Petra pool complex and gardens in the Hellenistic style. Though the Nabateans originally worshipped their traditional gods in symbolic form such as stone blocks or pillars, during the Hellenistic period they began to identify their gods with Greek gods and depict them in figurative forms influenced by Greek sculpture.[citation needed] Nabatean art shows Greek influences, and paintings have been found depicting Dionysian scenes.[82] They also slowly adopted Greek as a language of commerce along with Aramaic and Arabic.

Cappadocia

[edit]Cappadocia, a mountainous region situated between Pontus and the Taurus mountains, was ruled by a Persian dynasty. Ariarathes I (332–322 BC) was the satrap of Cappadocia under the Persians and after the conquests of Alexander he retained his post. After Alexander's death he was defeated by Eumenes and crucified in 322 BC, but his son, Ariarathes II managed to regain the throne and maintain his autonomy against the warring Diadochi.

In 255 BC, Ariarathes III took the title of king and married Stratonice, a daughter of Antiochus II, remaining an ally of the Seleucid kingdom. Under Ariarathes IV, Cappadocia came into relations with Rome, first as a foe espousing the cause of Antiochus the Great, then as an ally against Perseus of Macedon and finally in a war against the Seleucids. Ariarathes V also waged war with Rome against Aristonicus, a claimant to the throne of Pergamon, and their forces were annihilated in 130 BC. This defeat allowed Pontus to invade and conquer the kingdom.

Armenia

[edit]Orontid Armenia formally passed to the empire of Alexander the Great following his conquest of Persia. Alexander appointed an Orontid named Mithranes to govern Armenia. Armenia later became a vassal state of the Seleucid Empire, but it maintained a considerable degree of autonomy, retaining its native rulers. Towards the end 212 BC the country was divided into two kingdoms, Greater Armenia and Armenia Sophene, including Commagene or Armenia Minor. The kingdoms became so independent from Seleucid control that Antiochus III the Great waged war on them during his reign and replaced their rulers.

After the Seleucid defeat at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC, the kings of Sophene and Greater Armenia revolted and declared their independence, with Artaxias becoming the first king of the Artaxiad dynasty of Armenia in 188 BC. During the reign of the Artaxiads, Armenia went through a period of hellenization. Numismatic evidence shows Greek artistic styles and the use of the Greek language. Some coins describe the Armenian kings as "Philhellenes". During the reign of Tigranes the Great (95–55 BC), the kingdom of Armenia reached its greatest extent, containing many Greek cities, including the entire Syrian tetrapolis. Cleopatra, the wife of Tigranes the Great, invited Greeks such as the rhetor Amphicrates and the historian Metrodorus of Scepsis to the Armenian court, and—according to Plutarch—when the Roman general Lucullus seized the Armenian capital, Tigranocerta, he found a troupe of Greek actors who had arrived to perform plays for Tigranes.[83] Tigranes' successor Artavasdes II even composed Greek tragedies himself.

Parthia

[edit]

Parthia was a north-eastern Iranian satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire which later passed on to Alexander's empire. Under the Seleucids, Parthia was governed by various Greek satraps such as Nicanor and Philip. In 247 BC, following the death of Antiochus II Theos, Andragoras, the Seleucid governor of Parthia, proclaimed his independence and began minting coins showing himself wearing a royal diadem and claiming kingship. He ruled until 238 BC when Arsaces, the leader of the Parni tribe conquered Parthia, killing Andragoras and inaugurating the Arsacid dynasty. Antiochus III recaptured Arsacid controlled territory in 209 BC from Arsaces II. Arsaces II sued for peace and became a vassal of the Seleucids. It was not until the reign of Phraates I (c. 176–171 BC), that the Arsacids would again begin to assert their independence.[84]

During the reign of Mithridates I of Parthia, Arsacid control expanded to include Herat (in 167 BC), Babylonia (in 144 BC), Media (in 141 BC), Persia (in 139 BC), and large parts of Syria (in the 110s BC). The Seleucid–Parthian wars continued as the Seleucids invaded Mesopotamia under Antiochus VII Sidetes (reigned 138–129 BC), but he was eventually killed by a Parthian counterattack. After the fall of the Seleucid dynasty, the Parthians fought frequently against neighbouring Rome in the Roman–Parthian Wars (66 BC – AD 217). Abundant traces of Hellenism continued under the Parthian empire. The Parthians used Greek as well as their own Parthian language (though lesser than Greek) as languages of administration and also used Greek drachmas as coinage. They enjoyed Greek theater, and Greek art influenced Parthian art. The Parthians continued worshipping Greek gods syncretized together with Iranian deities. Their rulers established ruler cults in the manner of Hellenistic kings and often used Hellenistic royal epithets.

The Hellenistic influence in Iran was significant in terms of scope, but not depth and durability—unlike the Near East, the Iranian–Zoroastrian ideas and ideals remained the main source of inspiration in mainland Iran, and was soon revived in late Parthian and Sasanian periods.[85]

Judea

[edit]

During the Hellenistic period, Judea became a frontier region between the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Egypt and therefore was often the frontline of the Syrian wars, changing hands several times during these conflicts.[86] Under the Hellenistic kingdoms, Judea was ruled by the hereditary office of the High Priest of Israel as a Hellenistic vassal. This period also saw the rise of a Hellenistic Judaism, which first developed in the Jewish diaspora of Alexandria and Antioch, and then spread to Judea. The major literary product of this cultural syncretism is the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible from Biblical Hebrew and Biblical Aramaic to Koiné Greek. The reason for the production of this translation seems to be that many of the Alexandrian Jews had lost the ability to speak Hebrew and Aramaic.[87]

Between 301 and 219 BC the Ptolemies ruled Judea in relative peace, and Jews often found themselves working in the Ptolemaic administration and army, which led to the rise of a Hellenized Jewish elite class (e.g. the Tobiads). The wars of Antiochus III brought the region into the Seleucid empire; Jerusalem fell to his control in 198 BC and the Temple was repaired and provided with money and tribute.[88] Antiochus IV Epiphanes sacked Jerusalem and looted the Temple in 169 BC after disturbances in Judea during his abortive invasion of Egypt. Antiochus then banned key Jewish religious rites and traditions in Judea. He may have been attempting to Hellenize the region and unify his empire and the Jewish resistance to this eventually led to an escalation of violence. Whatever the case, tensions between pro- and anti-Seleucid Jewish factions led to the 174–135 BC Maccabean Revolt of Judas Maccabeus (whose victory is celebrated in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah).[89]

Modern interpretations see this period as a civil war between Hellenized and orthodox forms of Judaism.[90][91] Out of this revolt was formed an independent Jewish kingdom known as the Hasmonean dynasty, which lasted from 165 BC to 63 BC. The Hasmonean dynasty eventually disintegrated in a civil war, which coincided with civil wars in Rome. The last Hasmonean ruler, Antigonus II Mattathias, was captured by Herod and executed in 37 BC. In spite of originally being a revolt against Greek overlordship, the Hasmonean kingdom and also the Herodian kingdom which followed gradually became more and more hellenized. From 37 BC to 4 BC, Herod the Great ruled as a Jewish-Roman client king appointed by the Roman Senate. He considerably enlarged the Temple (see Herod's Temple), making it one of the largest religious structures in the world. The style of the enlarged temple and other Herodian architecture shows significant Hellenistic architectural influence. His son, Herod Archelaus, ruled from 4 BC to AD 7 when he was deposed for the formation of Roman Judea.[92]

Kingdom of Pontus

[edit]

The Kingdom of Pontus was a Hellenistic kingdom on the southern coast of the Black Sea. It was founded by Mithridates I in 291 BC and lasted until its conquest by the Roman Republic in 63 BC. Despite being ruled by a dynasty which was a descendant of the Persian Achaemenid Empire it became hellenized due to the influence of the Greek cities on the Black Sea and its neighboring kingdoms. Pontic culture was a mix of Greek and Iranian elements; the most hellenized parts of the kingdom were on the coast, populated by Greek colonies such as Trapezus and Sinope, the latter of which became the capital of the kingdom. Epigraphic evidence also shows extensive Hellenistic influence in the interior. During the reign of Mithridates II, Pontus was allied with the Seleucids through dynastic marriages. By the time of Mithridates VI Eupator, Greek was the official language of the kingdom, though Anatolian languages continued to be spoken.

The kingdom grew to its largest extent under Mithridates VI, who conquered Colchis, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Bithynia, Lesser Armenia, the Bosporan Kingdom, the Greek colonies of the Tauric Chersonesos and, for a brief time, the Roman province of Asia. Mithridates, himself of mixed Persian and Greek ancestry, presented himself as the protector of the Greeks against the 'barbarians' of Rome styling himself as "King Mithridates Eupator Dionysus"[93] and as the "great liberator". Mithridates also depicted himself with the anastole hairstyle of Alexander and used the symbolism of Herakles, from whom the Macedonian kings claimed descent. After a long struggle with Rome in the Mithridatic wars, Pontus was defeated; part of it was incorporated into the Roman Republic as the province of Bithynia, while Pontus' eastern half survived as a client kingdom.

Other realms

[edit]Greco-Bactrians

[edit]

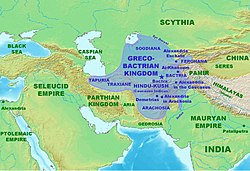

The Greek kingdom of Bactria began as a breakaway satrapy of the Seleucid empire, which, because of the size of the empire, had significant freedom from central control. Between 255 and 246 BC, the governor of Bactria, Sogdiana and Margiana (most of present-day Afghanistan), one Diodotus, took this process to its logical extreme and declared himself king. Diodotus II, son of Diodotus, was overthrown in about 230 BC by Euthydemus, possibly the satrap of Sogdiana, who then started his own dynasty. In c. 210 BC, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom was invaded by a resurgent Seleucid empire under Antiochus III the Great. While victorious in the field, it seems Antiochus came to realise that there were advantages in the status quo (perhaps sensing that Bactria could not be governed from Syria), and married one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son, thus legitimizing the Greco-Bactrian dynasty. Soon afterwards the Greco-Bactrian kingdom seems to have expanded, possibly taking advantage of the defeat of the Parthian king Arsaces II by Antiochus.

According to Strabo, the Greco-Bactrians seem to have had contacts with Han China through the Silk Road trade routes (Strabo, XI.11.1). There is evidence of technology exchange between Bactria and China around this time in the form of metal alloys such as Copper-nickel, which was then unknown to the West.[94] An interesting facet of this cultural exchange was the Ferghana horse, renowned for its strength and endurance. These horses were highly valued and played a crucial role in military and trade activities. The Greco-Bactrians likely facilitated their exchange along the Silk Road, significantly enhancing their cultural and economic influence across Central Asia. The demand for these horses even reached the Han Dynasty in China, underscoring their importance and the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations.[95] Indian sources also maintain religious contact between Buddhist monks and the Greeks, and some Greco-Bactrians did convert to Buddhism. Demetrius, son and successor of Euthydemus, invaded north-western India around 180 BC, after the destruction of the Mauryan Empire there; the Mauryans were probably allies of the Bactrians (and Seleucids). The exact justification for the invasion remains unclear, but after 180 BC, the Greeks ruled over parts of northwestern India. This period also marks the beginning of the obfuscation of Greco-Bactrian history. Demetrius possibly died in about 180 BC; numismatic evidence suggests the existence of several other kings shortly thereafter. It is probable that at this point the Greco-Bactrian kingdom split into several semi-independent regions for some years, often warring amongst themselves. King Heliocles was the last Greek to clearly rule Bactria, his power collapsing in the face of central Asian tribal invasions (Scythian and Yuezhi), by about 130 BC. However, Greek urban civilisation seems to have continued in Bactria after the fall of the kingdom, having a hellenising effect on the tribes which had displaced Greek rule. The Kushan Empire which followed continued to use Greek on their coinage and Greeks continued being influential in the empire.

Indo-Greek kingdoms

[edit]

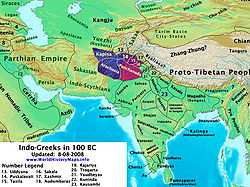

The separation of the Indo-Greek kingdom from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom resulted in an even more isolated position, and thus the details of the Indo-Greek kingdom are even more obscure than for Bactria. Many supposed kings in India are known only because of coins bearing their name. After the death of the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius, civil wars between Bactrian kings in India allowed Apollodotus I (from c. 180/175 BC) to make himself independent as the first proper Indo-Greek king (who did not rule from Bactria). Large numbers of his coins have been found in India, and he seems to have reigned in Gandhara as well as western Punjab. Apollodotus I was succeeded by or ruled alongside Antimachus II, likely the son of the Bactrian king Antimachus I.[96]

In about 155 or 165 BC, a king named Menander rose to power. Menander was the most successful of the Indo-Greek kings and he seems to have been a great patron of Buddhism. He probably became a Buddhist and is remembered in some Buddhist texts as 'Milinda'. He also expanded the kingdom further east into Punjab, though these conquests were rather ephemeral. After the death of Menander (c. 130 BC), the Kingdom appears to have fragmented, with several 'kings' attested contemporaneously in different regions. This inevitably weakened the Greek position, and territory seems to have been lost progressively. Around 70 BC, the western regions of Arachosia and Paropamisadae were lost to tribal invasions, presumably by those tribes responsible for the end of the Bactrian kingdom. The resulting Indo-Scythian kingdom seems to have gradually pushed the remaining Indo-Greek kingdom towards the east. The Indo-Greek kingdom appears to have lingered on in western Punjab until about AD 10, at which time it was finally ended by the Indo-Scythians. Strato III was the last of the dynasty of Diodotus was the last of the line of Diodotus and independent Hellenistic king to rule at his death in 10 AD.[97][98]

After conquering the Indo-Greeks, the Kushan empire took over Greco-Buddhism, the Greek language, Greek script, Greek coinage and artistic styles. Greeks continued being an important part of the cultural world of India for generations. The depictions of the Buddha appear to have been influenced by Greek culture: Buddha representations in the Ghandara period often showed Buddha under the protection of Herakles.[99] Several references in Indian literature praise the knowledge of the Yavanas or the Greeks. The Mahabharata compliments them as "the all-knowing Yavanas" (sarvajñā yavanā); e.g., "The Yavanas, O king, are all-knowing; the Suras are particularly so. The mlecchas are wedded to the creations of their own fancy",[100] such as flying machines that are generally called vimanas. The "Brihat-Samhita" of the mathematician Varahamihira says: "The Greeks, though impure, must be honored since they were trained in sciences and therein, excelled others...".[101]

Rise of Rome

[edit]

Widespread Roman interference in the Greek world was probably inevitable given the general manner of the ascendancy of the Roman Republic. This Roman-Greek interaction began as a consequence of the Greek city-states located along the coast of southern Italy. Rome had come to dominate the Italian peninsula, and desired the submission of the Greek cities to its rule. Although they initially resisted, allying themselves with Pyrrhus of Epirus, and defeating the Romans at several battles, the Greek cities were unable to maintain this position and were absorbed by the Roman republic. Shortly afterward, Rome became involved in Sicily, fighting against the Carthaginians in the First Punic War. The result was the complete conquest of Sicily, including its previously powerful Greek cities, by the Romans.[102]

After the Second Punic War, the Romans looked to re-assert their influence in the Balkans, and to curb the expansion of Philip V of Macedon. A pretext for war was provided by Philip's refusal to end his war with Attalid Pergamum and Rhodes, both Roman allies.[103] The Romans, also allied with the Aetolian League of Greek city-states (which resented Philip's power), thus declared war on Macedon in 200 BC, starting the Second Macedonian War. This ended with a decisive Roman victory at the Battle of Cynoscephalae (197 BC).[104] Like most Roman peace treaties of the period, the resultant 'Peace of Flaminius' was designed utterly to crush the power of the defeated party; a massive indemnity was levied, Philip's fleet was surrendered to Rome, and Macedon was effectively returned to its ancient boundaries, losing influence over the city-states of southern Greece, and land in Thrace and Asia Minor. The result was the end of Macedon as a major power in the Mediterranean.[105]

In less than twenty years, Rome had destroyed the power of one of the successor states, crippled another, and firmly entrenched its influence over Greece. This was primarily a result of the over-ambition of the Macedonian kings, and their unintended provocation of Rome, though Rome was quick to exploit the situation. In another twenty years, the Macedonian kingdom was no more. Seeking to re-assert Macedonian power and Greek independence, Philip V's son Perseus incurred the wrath of the Romans, resulting in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).[105][106] Victorious, the Romans abolished the Macedonian kingdom, replacing it with four puppet republics until it was formally annexed as a Roman province after yet another rebellion under Andriscus.[107] Rome now demanded that the Achaean League, the last stronghold of Greek independence, be dissolved. The Achaeans refused and declared war on Rome. Most of the Greek cities rallied to the Achaeans' side, even slaves were freed to fight for Greek independence.[108] The Roman consul Lucius Mummius advanced from Macedonia and defeated the Greeks at Corinth, which was razed to the ground. In 146 BC, the Greek peninsula, though not the islands, became a Roman protectorate. Roman taxes were imposed, except in Athens and Sparta, and all the cities had to accept rule by Rome's local allies.[109]

The Attalid dynasty of Pergamum lasted little longer; a Roman ally until the end, its final king Attalus III died in 133 BC without an heir, and taking the alliance to its natural conclusion, willed Pergamum to the Roman Republic.[110] The final Greek resistance came in 88 BC, when King Mithridates of Pontus rebelled against Rome, captured Roman held Anatolia, and massacred up to 100,000 Romans and Roman allies across Asia Minor. Many Greek cities, including Athens, overthrew their Roman puppet rulers and joined him in the Mithridatic wars. When he was driven out of Greece by the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the latter laid siege to Athens and razed the city. Mithridates was finally defeated by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) in 65 BC.[111][112] Further ruin was brought to Greece by the Roman civil wars, which were partly fought in Greece. Finally, in 27 BC, Augustus directly annexed Greece to the new Roman Empire as the province of Achaea. The struggles with Rome had left Greece depopulated and demoralised.[113] Nevertheless, Roman rule at least brought an end to warfare, and cities such as Athens, Corinth, Thessaloniki and Patras soon recovered their prosperity.[114][115]

Eventually, instability in the near east resulting from the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Seleucid Empire caused the Roman proconsul Pompey the Great to abolish the Seleucid rump state, absorbing much of Syria into the Roman Republic.[110] Famously, the end of Ptolemaic Egypt came as the final act in the republican civil war between the Roman triumvirs Mark Anthony and Augustus Caesar. After the defeat of Anthony and his lover, the last Ptolemaic monarch, Cleopatra VII, at the Battle of Actium, Augustus invaded Egypt and took it as his own personal fiefdom.[110] He thereby completed the destruction of the Hellenistic kingdoms and transformed the Roman Republic into a monarchy, ending (in hindsight) the Hellenistic era.[116]

Hellenistic culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Spread

[edit]

Greek culture was at its height of world influence in the Hellenistic period. Hellenism or at least Philhellenism reached most regions on the frontiers of the Hellenistic kingdoms. Though some of these regions were not ruled by Greeks or even Greek speaking elites, Hellenistic influence can be seen in the historical record and material culture of these regions. Other regions had established contact with Greek colonies before this period, and simply saw a continued process of Hellenization and intermixing.[117][118]

The spread of Greek culture and language throughout the Near East and Asia owed much to the development of newly founded cities and deliberate colonization policies by the successor states, which in turn was necessary for maintaining their military forces. Settlements such as Ai-Khanoum, on trade routes, allowed Greek culture to mix and spread. The language of Philip II's and Alexander's court and army (which was made up of various Greek and non-Greek speaking peoples) was a version of Attic Greek, and over time this language developed into Koine, the lingua franca of the successor states. The spread of Greek influence and language is also shown through ancient Greek coinage. Portraits became more realistic, and the obverse of the coin was often used to display a propagandistic image, commemorating an event or displaying the image of a favored god. The use of Greek-style portraits and Greek language continued under the Roman, Parthian, and Kushan empires, even as the use of Greek was in decline.[119][120]

Institutions

[edit]In some fields Hellenistic culture thrived, particularly in its preservation of the past. The states of the Hellenistic period were deeply fixated with the past and its seemingly lost glories.[121] The preservation of many classical and archaic works of art and literature (including the works of the three great classical tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) are due to the efforts of the Hellenistic Greeks. The Mouseion and Library of Alexandria were the center of this conservationist activity. With the support of royal stipends, Alexandrian scholars collected, translated, copied, classified, and critiqued every book they could find. Most of the great literary figures of the Hellenistic period studied at Alexandria and conducted research there. They were scholar poets, writing not only poetry but treatises on Homer and other archaic and classical Greek literature.[122]

Athens retained its position as the most prestigious seat of higher education, especially in the domains of philosophy and rhetoric, with considerable libraries and philosophical schools.[123] Alexandria had the monumental Mouseion (a research center) and Library of Alexandria, with a estimated collection of 500,000 or more volumes.[123] The city of Pergamon also had a large library and became a major center of book production.[123] The island of Rhodes had a library and also boasted a famous finishing school for politics and diplomacy. Libraries were also present in Antioch, Pella, and Kos. Cicero was educated in Athens and Mark Antony in Rhodes.[123] Antioch was founded as a metropolis and center of Greek learning which retained its status into the era of Christianity.[123] Seleucia replaced Babylon as the metropolis of the lower Tigris.

The identification of local gods with similar Greek deities, a practice termed 'Interpretatio graeca', stimulated the building of Greek-style temples, and Greek culture in the cities meant that buildings such as gymnasia and theaters became common. Many cities maintained nominal autonomy while under the rule of the local king or satrap, and often had Greek-style institutions. Greek dedications, statues, architecture, and inscriptions have all been found. However, local cultures were not replaced, and mostly went on as before, but now with a new Greco-Macedonian or otherwise Hellenized elite. An example that shows the spread of Greek theater is Plutarch's story of the death of Crassus, in which his head was taken to the Parthian court and used as a prop in a performance of The Bacchae. Theaters have also been found: for example, in Ai-Khanoum on the edge of Bactria, the theater has 35 rows – larger than the theater in Babylon.

Hellenization and acculturation

[edit]

The concept of Hellenization, meaning the adoption of Greek culture in non-Greek regions, has long been controversial. Undoubtedly Greek influence did spread through the Hellenistic realms, but to what extent, and whether this was a deliberate policy or mere cultural diffusion, have been hotly debated.

It seems likely that Alexander himself pursued policies which led to Hellenization, such as the foundations of new cities and Greek colonies. While it may have been a deliberate attempt to spread Greek culture (or as Arrian says, "to civilise the natives"), it is more likely that it was a series of pragmatic measures designed to aid in the rule of his enormous empire.[28] Cities and colonies were centers of administrative control and Macedonian power in a newly conquered region. Alexander also seems to have attempted to create a mixed Greco-Persian elite class as shown by the Susa weddings and his adoption of some forms of Persian dress and court culture. He also brought Persian and other non-Greek peoples into his military and even the elite cavalry units of the companion cavalry. Again, it is probably better to see these policies as a pragmatic response to the demands of ruling a large empire[28] than to any idealized attempt to bringing Greek culture to the 'barbarians'. This approach was bitterly resented by the Macedonians and discarded by most of the Diadochi after Alexander's death. These policies can also be interpreted as the result of Alexander's possible megalomania[124] during his later years.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the influx of Greek colonists into the new realms continued to spread Greek culture into Asia. The founding of new cities and military colonies continued to be a major part of the Successors' struggle for control of any particular region, and these continued to be centers of cultural diffusion. The spread of Greek culture under the Successors seems mostly to have occurred with the spreading of Greeks themselves, rather than as an active policy.

Throughout the Hellenistic world, these Greco-Macedonian colonists considered themselves by and large superior to the native "barbarians" and excluded most non-Greeks from the upper echelons of courtly and government life. Most of the native population was not Hellenized, had little access to Greek culture and often found themselves discriminated against by their Hellenic overlords.[125] Gymnasiums and their Greek education, for example, were for Greeks only. Greek cities and colonies may have exported Greek art and architecture as far as the Indus, but these were mostly enclaves of Greek culture for the transplanted Greek elite. The degree of influence that Greek culture had throughout the Hellenistic kingdoms was therefore highly localized and based mostly on a few great cities like Alexandria and Antioch. Some natives did learn Greek and adopt Greek ways, but this was mostly limited to a few local elites who were allowed to retain their posts by the Diadochi and also to a small number of mid-level administrators who acted as intermediaries between the Greek speaking upper class and their subjects. In the Seleucid Empire, for example, this group amounted to only 2.5 percent of the official class.[126]

Hellenistic art nevertheless had a considerable influence on the cultures that had been affected by the Hellenistic expansion. As far as the Indian subcontinent, Hellenistic influence on Indian art was broad and far-reaching, and had effects for several centuries following the forays of Alexander the Great.

Despite their initial reluctance, the Successors seem to have later deliberately naturalized themselves to their different regions, presumably in order to help maintain control of the population.[127] In the Ptolemaic kingdom, we find some Egyptianized Greeks by the 2nd century onwards. In the Indo-Greek kingdom we find kings who were converts to Buddhism (e.g., Menander). The Greeks in the regions therefore gradually become 'localized', adopting local customs as appropriate. In this way, hybrid 'Hellenistic' cultures naturally emerged, at least among the upper echelons of society.

The trends of Hellenization were therefore accompanied by Greeks adopting native ways over time, but this was widely varied by place and by social class. The farther away from the Mediterranean and the lower in social status, the more likely that a colonist was to adopt local ways, while the Greco-Macedonian elites and royal families usually remained thoroughly Greek and viewed most non-Greeks with disdain. It was not until Cleopatra VII that a Ptolemaic ruler bothered to learn the Egyptian language of their subjects.

Religion

[edit]

In the Hellenistic period, there was much continuity in Greek religion: the Greek gods continued to be worshiped, and the same rites were practiced as before. However the socio-political changes brought on by the conquest of the Persian empire and Greek emigration abroad meant that change also came to religious practices. This varied greatly by location. Athens, Sparta and most cities in the Greek mainland did not see much religious change or new gods (with the exception of the Egyptian Isis in Athens),[128] while the multi-ethnic Alexandria had a very varied group of gods and religious practices, including Egyptian, Jewish and Greek. Greek emigres brought their Greek religion everywhere they went, even as far as India and Afghanistan. Non-Greeks also had more freedom to travel and trade throughout the Mediterranean and in this period we can see Egyptian gods such as Serapis, and the Syrian gods Atargatis and Hadad, as well as a Jewish synagogue, all coexisting on the island of Delos alongside classical Greek deities.[129] A common practice was to identify Greek gods with native gods that had similar characteristics and this created new fusions like Zeus-Ammon, Aphrodite Hagne (a Hellenized Atargatis) and Isis-Demeter. Greek emigres faced individual religious choices they had not faced on their home cities, where the gods they worshiped were dictated by tradition.

Hellenistic monarchies were closely associated with the religious life of the kingdoms they ruled. This had already been a feature of Macedonian kingship, which had priestly duties.[130] Hellenistic kings adopted patron deities as protectors of their house and sometimes claimed descent from them. The Seleucids for example took on Apollo as patron, the Antigonids had Herakles, and the Ptolemies claimed Dionysus among others.[131]

The worship of dynastic ruler cults was also a feature of this period, most notably in Egypt, where the Ptolemies adopted earlier Pharaonic practice, and established themselves as god-kings. These cults were usually associated with a specific temple in honor of the ruler such as the Ptolemaieia at Alexandria and had their own festivals and theatrical performances. The setting up of ruler cults was more based on the systematized honors offered to the kings (sacrifice, proskynesis, statues, altars, hymns) which put them on par with the gods (isotheism) than on actual belief of their divine nature. According to Peter Green, these cults did not produce genuine belief of the divinity of rulers among the Greeks and Macedonians.[132] The worship of Alexander was also popular, as in the long lived cult at Erythrae and of course, at Alexandria, where his tomb was located.