Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Devolved, reserved and excepted matters

View on Wikipedia| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

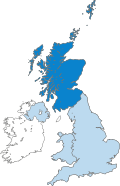

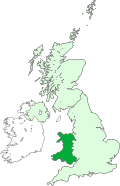

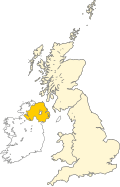

In the United Kingdom, devolved matters are the areas of public policy where the Parliament of the United Kingdom has devolved its legislative power to the national legislatures of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, while reserved matters and excepted matters are the areas where the UK Parliament retains exclusive power to legislate.

Devolution in the United Kingdom is regarded as the decentralisation of power from the UK Government, with powers devolved to the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government, the Northern Ireland Assembly and Northern Ireland Executive and the Welsh Parliament and Welsh Government, in all areas except those which are reserved or excepted.[1] Amongst the four countries of the United Kingdom, Scotland has the most extensive devolved powers controlled by the Scottish Parliament, with the Scottish Government being described as the "most powerful devolved government in the world".[2][3]

In theory, reserved matters could be devolved at a later date, whereas excepted matters (defined only in relation to Northern Ireland) are not supposed to be considered for further devolution. In practice, the difference is minor as Westminster is responsible for all the powers on both lists and its consent is both necessary and sufficient to devolve them. Because Westminster acts with sovereign supremacy, it is still able to pass legislation for all parts of the United Kingdom, including in relation to devolved matters.[4]

Devolution of powers

[edit]The devolution of powers are set out in three main acts legislated by the UK Parliament for each of the devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The acts also include subsequent amendments, which devolved further powers to the administrations:

- Northern Ireland Act 1998 amended by the Northern Ireland Act 2006.

- Scotland Act 1998 amended by the Scotland Act 2012 and the Scotland Act 2016.

- Government of Wales Act 1998 amended by the Government of Wales Act 2006, the Wales Act 2014 and the Wales Act 2017

As a result of the historical and administrative differences between Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, matters which are devolved and which are reserved, varies between each country.[5]

In Northern Ireland, the powers of the Northern Ireland Assembly do not cover reserved matters or excepted matters.

In Scotland, a list of reserved matters is explicitly listed in the Scotland Act 1998 (and amended by the Scotland Acts of 2012 and 2016). Any matter not explicitly listed in the Act is implicitly devolved to the Scottish Parliament. The Scottish Parliament controls around 60% of spending in Scotland. Any form of revenue raised within the Scottish economy will remain in Scotland, whilst the Scottish Government is permitted to retain the first ten percentage points of VAT collected in Scotland (50% of revenue). Additionally, the Scottish Government has control over Air Passenger Duty (the tax to be paid by air travellers leaving Scotland), Aggregates Levy (the power to tax companies involved in extracting aggregates within Scotland) and has additional borrowing powers which permits the Scottish Government to borrow up to 10% of its budget annually.[6] The Scottish Government can borrow up to £3.5 billion in additional funding to invest in public services, such as schools, transportation networks and healthcare, amongst other areas.[7]

In Wales, a list of reserved matters is explicitly listed under the provisions of the Wales Act 2017. Any matter not explicitly listed in the Act is implicitly devolved to the Senedd. Before 2017, a list of matters was explicitly devolved to the then known National Assembly for Wales and any matter not listed in the Act was implicitly reserved to Westminster. In Wales, the Welsh Government became responsible for income tax only in 2019, meaning individuals with their permanent residence located in Wales and, as a result, pay Income Tax in Wales, will now pay Welsh rates of Income Tax which is set by the Welsh Government. Additionally, the Welsh Government has been granted powers over Land Transaction Tax and Landfill Disposals Tax.[8]

Scotland and Wales

[edit]

The devolution schemes in Scotland and Wales are set up in a similar manner. The Parliament of the United Kingdom has granted legislative power to the Scottish Parliament and the Senedd through the Scotland Act 1998 and the Government of Wales Act 2006 respectively. These Acts set out the matters still dealt with by the UK Government, referred to as reserved matters.

Anything not listed as a specific reserved matter in the Scotland Act or the Wales Act is devolved to that nation. The UK Parliament can still choose to legislate over devolved areas.[4]

The legal ability of the Scottish Parliament or Senedd to legislate (its "legislative competence") on a matter is largely determined by whether it is reserved or not.[9][10][11][12] Additionally, the Scottish Parliament can overturn any piece of existing UK legislation and introduce legislation in areas not retained by Westminster, whilst the Welsh Assembly is only permitted to amend existing UK legislation passed by the UK Parliament in the areas devolved to Wales.

The Scottish Parliament has substantially more powers than both the Welsh Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly, with the Scottish Government being described as "one of the most powerful devolved governments in the world".[13] The Scottish Parliament has the power to vary the basic rate of income tax whilst the Welsh Parliament relies only on funding by the central UK government. Additionally, Scotland has been granted substantially more powers on international affairs and foreign engagement. Despite foreign affairs remaining a reserved matter to the UK parliament, the Scottish Government has been granted authority to be more directly involved in government decision making on European Union matters and relations. In Wales, this is not the case, with the Welsh Government having no additional power on international relations, with this right being retained by the Secretary of State for Wales in the UK Government.[14]

Scotland has the most extensive tax powers of any of the devolved governments, followed by Wales and Northern Ireland. The three devolved governments have full legislative power over council tax, business tax, whilst Scotland and Wales has additional tax powers in areas such as property tax, landfill tax, stamp tax and some aspects of income tax, whilst the Northern Ireland Executive does not. Furthermore, Scotland has legislative control over areas such as air passenger duty, value added tax (VAT) and aggregates levy. The Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive do not have control over those areas in their respective countries.[15]

Devolved powers in Scotland

[edit]

Of the three countries within the United Kingdom with devolved parliaments, the Scottish Parliament has the most extensive devolved powers in which it is responsible for.[16]

The responsibilities of the Scottish Ministers broadly follow those of the Scottish Parliament provided for in the Scotland Act 1998 and subsequent UK legislation. Where pre-devolution legislation of the UK Parliament provided that certain functions could be performed by UK Government ministers, these functions were transferred to the Scottish Ministers if they were within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

Functions which were devolved under the Scotland Act 1998 included:[17]

- Healthcare – NHS Scotland, mental health, dentistry, social care

- Education – pre-school, primary, secondary, further, higher and lifelong education, as well as educational training policy and programmes

- Student Awards Agency for Scotland

- Scottish Public Pensions Agency

- Scots law and justice – civil justice, civil law and procedure, courts, criminal justice, criminal law and procedure, debt and bankruptcy, family law, legal aid, the legal profession, property law and Disclosure Scotland

- Most aspects of transport – setting drink and drug-driving limits, speed limits, some aspects of railways, including Scottish passenger rail franchises (ScotRail), concessionary travel schemes, cycling, parking, local road pricing, congestion charging, promotion of road safety and road signs

- Environment – environmental protection policy, climate change, pollution, waste management, water supplies and sewerage, national parks and flood and coastal protection

- Policing and the Scottish Prison Service

- Planning system in Scotland

- Rural Affairs (including Cairngorms National Park Authority, Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park Authority, Crofting Commission, Scottish Forestry, Forestry and Land Scotland, Scottish Environment Protection Agency, NatureScot and Scottish Land Commission)

- Housing – housing policy, Scottish Housing Regulator, affordable homes, homelessness and homelessness legislation, child poverty, security of tenure, energy efficiency, homeownership, short assured tenancy, rented housing and rent control, Town Centre First, social rents, private sector housing security, Tenancy deposit schemes, Scottish Social Housing Charter and the Scottish Housing Quality Standard[18]

- Accountant in Bankruptcy

- Agriculture, forestry and fisheries – most aspects of animal welfare, but not including animal testing and research

- Sport and the arts – Creative Scotland, the National Gallery of Scotland, library and museum collections, the National Museum of Scotland, national performing companies and SportScotland, the national agency for sport

- Consumer advocacy and advice

- Tourism – VisitScotland and promotion of major events in Scotland

- Economic development

- Freedom of Information (FOI) requests

Subsequently, the Scotland Acts of 2012 and 2016 transferred powers over:[19][20]

- Some taxation powers – full control of Income Tax on income earned through employment, Land and Buildings Transaction Tax, Landfill Tax, Aggregates Levy, Air Departure Tax, Revenue Scotland

- Drink driving limits

- Air weapons

- Additional borrowing powers, up to the sum of £5 billion

- Transport police in Scotland

- Road signs, speed limits and abortion rights in Scotland

- Powers over Income Tax rates and bands on non-savings and non-dividend income

- Scottish Parliament and local authority elections

- Some social security powers (Adult Disability Payment, Pension Age Disability Payment, Funeral Support Payment, Carer Support Payment, Young Carer Grant, Job Start Payment, Winter Heating Payment)

- Crown Estate of Scotland – management of the Crown Estate's economic assets in Scotland

- Some aspects of the benefits system – Best Start Grant, Carer's Allowance Supplement, Child Disability Payment, Child Winter Heating Assistance, Funeral Support Payment, Universal Credit (although this is remains a reserved benefit, some powers over how it is paid have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament)

- Extended powers over Employment Support and the housing aspect of Universal Credit

- Some aspects of the energy network in Scotland – renewable energy, energy efficiency and onshore oil and gas licensing

- The right to receive half of the VAT raised in Scotland.[21]

- Some aspects of equality legislation in Scotland

- Gaming machine licensing

The 1998 Act also provided for orders to be made allowing Scottish Ministers to exercise powers of UK Government ministers in areas that remain reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Equally the Act allows for the Scottish Ministers to transfer functions to the UK Government ministers, or for particular "agency arrangements". This executive devolution means that the powers of the Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament are not identical.[22]

The members of the Scottish government have substantial influence over legislation in Scotland, putting forward the majority of bills that are successful in becoming Acts of the Scottish Parliament.[23]

Devolved powers in Wales

[edit]

Following the "yes" vote in the referendum on further law-making powers for the assembly on 3 March 2011, the Welsh Government is now entitled to propose bills to the National Assembly for Wales on subjects within 20 fields of policy. Subject to limitations prescribed by the Government of Wales Act 2006, Acts of the National Assembly may make any provision that could be made by Act of Parliament. The 20 areas of responsibility devolved to the National Assembly for Wales (and within which Welsh ministers exercise executive functions) are:

The Government of Wales Act 2006 updated the list of fields, as follows:[24]

- agriculture, fisheries, forestry and rural development

- ancient monuments and historic buildings

- culture

- economic development

- education and training

- environment

- fire and rescue services and promotion of fire safety

- food

- health and health services

- highways and transport

- housing

- local government

- the National Assembly for Wales

- public administration

- social welfare

- sport and recreation

- tourism

- town and country planning

- water and flood defence

- the Welsh language

Schedule 5 to the 2006 Act could be amended to add specific matters to the broad subject fields, thereby extending the legislative competence of the Assembly.[25]

Comparison between Scottish and Welsh powers

[edit]Specific reservations cover policy areas which can only be regulated by Westminster, listed under 'heads':

| Head | Scotland[26] | Wales[27] |

|---|---|---|

| Head A: Financial and economic matters | ||

| Fiscal, economic and monetary policy | Reserved | Reserved |

| The currency | Reserved | Reserved |

| Financial services and financial markets | Reserved | Reserved |

| Money laundering | Reserved | Reserved |

| Distribution of money from dormant bank accounts | Devolved | Reserved |

| Head B: Home affairs | ||

| Elections to the House of Commons | Reserved | Reserved |

| Emergency powers | Reserved | Reserved |

| Immigration and nationality | Reserved | Reserved |

| Extradition | Reserved | Reserved |

| National security and counter-terrorism | Reserved | Reserved |

| Policing, criminal investigations and private security | Devolved | Reserved |

| Anti-social behaviour and public order | Devolved | Reserved |

| Illicit drugs | Reserved | Reserved |

| Firearms | Reserved | Reserved |

| Air gun licensing | Devolved | Reserved |

| Betting, gaming and lotteries | Reserved | Reserved |

| Knives | Devolved | Reserved |

| Alcohol | Devolved | Reserved |

| Hunting with dogs and dangerous dogs | Devolved | Reserved |

| Prostitution, modern slavery | Devolved | Reserved |

| Film classification | Reserved | Reserved |

| Scientific procedures on live animals | Reserved | Reserved |

| Access to information | Reserved | Reserved[note 1] |

| Data protection | Reserved | Reserved |

| Lieutenancies | Reserved | Reserved |

| Charities | Devolved | Reserved |

| Head C: Trade and industry | ||

| Regulation of businesses, insolvency, competition law | Mostly reserved[note 2] | Reserved |

| Copyright and intellectual property | Reserved | Reserved |

| Import and export control | Reserved | Reserved |

| Sea fishing outside the Scottish zone | Reserved | — |

| Customer protection, product standards and product safety | Reserved | Reserved |

| Consumer advocacy and advice | Devolved | Reserved |

| Weights and measures | Reserved | Reserved |

| Telecommunications and postal services | Reserved | Reserved |

| Research councils | Reserved | Reserved |

| Industrial development and protection of trading interests | Reserved | Reserved |

| Water and sewerage outside Wales | — | Reserved |

| Pubs Code Regulations | Devolved | Reserved |

| Sunday trading | Devolved | Reserved |

| Head D: Energy | ||

| Electricity | Reserved | Reserved |

| Oil and gas, coal and nuclear energy | Reserved | Reserved |

| Heating and cooling | Devolved | Reserved |

| Energy efficiency | Reserved | Reserved |

| Head E: Transport | ||

| Traffic, vehicle and driver regulation | Reserved | Reserved |

| Train services | Partially devolved[note 3] | Reserved |

| Policing of railways and railway property | Devolved | Reserved |

| Navigation, shipping regulation and coastguard | Reserved | Reserved |

| Ports, harbours and shipping services outside Scotland or Wales | Reserved | Reserved |

| Air transport | Reserved | Reserved |

| Head F: Social security | ||

| National Insurance, social security schemes | Mostly reserved[note 4] | Reserved |

| Child support | Reserved | Reserved |

| Occupational, personal and war pensions | Reserved | Reserved |

| Public sector compensation | Devolved | Reserved |

| Head G: Regulation of the professions | ||

| Regulation of architects and auditors | Reserved | Reserved |

| Regulation of the health professions | Reserved | Reserved |

| Head H: Employment | ||

| Employment and industrial relations | Reserved | Reserved |

| Health and safety | Reserved | Reserved[note 5] |

| Industrial training boards | Devolved | Reserved |

| Job search and support | Reserved | Reserved |

| Head J: Health and medicines | ||

| Abortion | Devolved | Reserved |

| Xenotransplantation | Reserved | Reserved |

| Embryology, surrogacy and human genetics | Reserved | Reserved |

| Medicines, medical supplies and poisons | Reserved | Reserved[note 6] |

| Welfare foods | Devolved | Reserved |

| Head K: Media and culture | ||

| Broadcasting | Reserved | Reserved |

| Public lending right | Reserved | Reserved |

| Government Indemnity Scheme for cultural objects on loan | Reserved | Reserved |

| Safety of sports grounds | Devolved | Reserved |

| (Wales only) Part 1: The Constitution | ||

| The Crown Estate | Devolved | Reserved |

| (Wales only) Head L: Justice | ||

| The legal profession, legal services and legal aid | Devolved | Reserved |

| Coroners | Devolved[note 7] | Reserved |

| Arbitration | Devolved | Reserved |

| Mental capacity | Devolved | Reserved |

| Personal data | Devolved | Reserved |

| Public sector information and public records | Devolved | Reserved |

| Compensation for persons affected by crime | Devolved | Reserved |

| Prisons and offender management | Devolved | Reserved |

| Marriage, family relationships, matters concerning children | Devolved | Reserved |

| Gender recognition | Devolved[note 8][28] | Reserved |

| Registration of births, deaths and places of worship | Devolved | Reserved |

| (Wales only) Head M: Land and Agricultural Assets | ||

| Registration of land, agricultural charges and debentures | Devolved | Reserved |

| Certain powers relating to infrastructure planning, building regulation on Crown land, and land compensation |

Devolved | Reserved |

| Head L (Scotland) / Head N (Wales): Miscellaneous | ||

| Judicial salaries[note 9] | Reserved | Reserved |

| Equal opportunities | Reserved | Reserved |

| Control of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons | Reserved | Reserved |

| The Ordnance Survey | Reserved | Reserved |

| Time and calendars | Reserved | Reserved |

| Bank holidays | Devolved | Reserved |

| Outer space | Reserved | Reserved |

| Antarctica | Reserved | Reserved |

| Deep sea mining | Devolved | Reserved |

- ^ Appears under Head L in the Wales Act.

- ^ The Scotland Act contains numerous exceptions to the reserved powers concerning insolvency.

- ^ The construction of railways and the franchising of passenger services is devolved in Scotland.

- ^ These powers are mostly reserved, but the Scottish Parliament can legislate on various disability, industrial injuries, and carer's benefits, maternity, funeral and heating expenses benefits, discretionary housing payments, and various schemes for job search and support.

- ^ Appears under Head J in the Wales Act.

- ^ The matter of poisons appears under Head B in the Wales Act.

- ^ There are no coroners in Scotland. Instead, deaths that need to be investigated are reported to the procurator fiscal.

- ^ Gender recognition is not explicitly reserved under the Scotland Acts. However, in 2023 the Secretary of State vetoed the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill under Section 35 of the 1998 Act on the grounds that it affected the operation of the Equality Act 2010, which is reserved.

- ^ This is a specific reservation in Scotland and a general reservation in Wales.

The reserved matters continue to be controversial in some quarters [citation needed] and there are certain conflicts or anomalies. For example, in Scotland, the funding of Scottish Gaelic television is controlled by the Scottish Government, but broadcasting is a reserved matter, and while energy is a reserved matter, planning permission for power stations is devolved.

Northern Ireland

[edit]This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: repetition and non-chronological ordering. (February 2025) |

Devolved powers in Northern Ireland

[edit]- Health and social services

- Education

- Employment and skills

- Agriculture

- Social security

- Pensions and child support

- Housing

- Economic development

- Local government

- Environmental issues, including planning

- Transport

- Culture and sport

- The Northern Ireland Civil Service

- Equal opportunities

- Justice and policing

The Hillsborough Castle Agreement[29] on 5 February 2010 resulted in the following reserved powers being transferred to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 12 April 2010:[30]

- criminal law

- policing

- prosecution

- public order

- courts

- prisons and probation

Reserved (excepted) matters

[edit]Devolution in Northern Ireland was originally provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which stated that the Parliament of Northern Ireland could not make laws in the following main areas:[31]

- the Crown

- the Union with England, Scotland and Wales

- the making of peace or war

- the armed forces

- treaties or any relations with foreign states or dominions

- naturalization

- external trade

- navigation (including merchant shipping)

- submarine cables

- wireless telegraphy

- aerial navigation

- lighthouses

- currency

- copyright

This was the first practical example of devolution in the United Kingdom and followed three unsuccessful attempts to provide home rule for the whole island of Ireland:

Excepted matters are outlined in Schedule 2 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998:[32]

- the Crown

- Parliament of the United Kingdom

- international relations

- international development

- defence

- weapons of mass destruction

- honours

- treason

- immigration and nationality

- taxation

- national insurance

- elections

- currency

- national security

- nuclear energy

- space

Reserved matters are outlined in Schedule 3 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998:[33]

- navigation (including merchant shipping)

- civil aviation

- The foreshore, sea bed and subsoil and their natural resources

- postal services

- import and export controls, external trade

- national minimum wage

- financial services

- financial markets

- intellectual property

- units of measurement

- telecommunications, broadcasting, internet services

- The National Lottery

- xenotransplantation

- surrogacy

- human fertilisation and embryology

- human genetics

- consumer safety in relation to goods

Following the suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, policing and justice powers transferred to the UK Parliament and were subsequently administered by the Northern Ireland Office within the UK Government. These powers were not devolved following the Belfast Agreement.

Some policing and justice powers remain reserved to Westminster:[34]

- the prerogative of mercy in terrorism cases

- drug classification

- the National Crime Agency

- accommodation of prisoners in separated conditions

- parades

- security of explosives

A number of policing and justice powers remain excepted matters and were not devolved. These include:

- extradition (as an international relations matter)

- military justice (as a defence matter)

- immigration

- national security (including intelligence services)

Irish unionists initially opposed home rule, but later accepted it for Northern Ireland, where they formed a majority. (The rest of the island became independent as what is now the Republic of Ireland.)

History of Northern Irish devolution

[edit]The Parliament of Northern Ireland was suspended on 30 March 1972 by the Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972,[35] with Stormont's legislative powers being transferred to the Queen in Council.

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was abolished outright by the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973;[36] legislative competence was conferred instead on the Northern Ireland Assembly. The 1973 Act set out a list of excepted matters (sch. 2) and "minimum" reserved matters (sch. 3).

The new constitutional arrangements quickly failed, and the Assembly was suspended on 29 May 1974,[37] having only passed two Measures.[citation needed]

The Assembly was dissolved under the Northern Ireland Act 1974,[38][39] which transferred its law-making power to the Queen in Council once again. The 1974 framework of powers continued in place until legislative powers were transferred to the present Northern Ireland Assembly on 2 December 1999,[40] under the Northern Ireland Act 1998, following the Belfast Agreement of 10 April 1998.

Parity

[edit]Northern Ireland has parity with Great Britain in three areas:

Policy in these areas is technically devolved but, in practice, follows policy set by the UK Parliament to provide consistency across the United Kingdom.[41]

Common devolved and reserved powers

[edit]Devolved

[edit]- agriculture, fisheries, forestry and rural development

- borrowing powers (Scotland only)

- culture

- the Crown Estate (Scotland only)

- economic development

- education and training

- environment

- fire and rescue services and promotion of fire safety

- food

- health and health services

- housing

- justice and policing (in Scotland & Northern Ireland only)

- local government

- public administration

- social welfare

- sport and recreation

- tourism

- town and country planning

- water and flood defence

Reserved

[edit]Reserved matters are subdivided into two categories: General reservations and specific reservations.

General reservations cover major issues which are always handled centrally by the Parliament in Westminster:[26][27]

- the Crown

- the constitutional matters listed in Schedule 5 of the 1998 Act

- the UK Parliament

- registration and funding of political parties

- the making of peace or war

- international relations and treaties

- international development

- international trade

- the Civil Service of the United Kingdom

- defence

- treason

Additionally, in Wales, all matters concerning the single legal jurisdiction of England and Wales are reserved, including courts, tribunals, judges, civil and criminal legal proceedings, pardons for criminal offences, private international law, and judicial review of administrative action. An exception in Wales allows the Senedd to create Wales-specific tribunals that are not concerned with reserved matters.

References

[edit]- ^ "Devolution". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "The progress of devolution - Erskine May - UK Parliament". erskinemay.parliament.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "5 reasons why Scotland is more powerful as part of the United Kingdom". GOV.UK. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ a b "Sewel Convention". Institute for Government. 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Devolution Toolkit" (PDF). publishing.service.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Scotland: Tax and revenue - at a glance". GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "UK Government confirms increase to Scottish Government borrowing". GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Tax is changing in Wales". GOV.UK. 5 April 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Scotland Act 1998".

- ^ "Scotland Act 1998".

- ^ "Scotland Act 1998".

- ^ "Scotland Act 1998".

- ^ "5 reasons why Scotland is more powerful as part of the United Kingdom". GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Scottish Referendums". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Devolution at 25: how has productivity changed in the devolved nations?". Economics Observatory. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "The progress of devolution - Erskine May - UK Parliament". erskinemay.parliament.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "What is Devolution?". Scottish Parliament. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ "01 Housing in Scotland: A Distinctive Approach". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "What the Scottish Government does". Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Devolved and Reserved Powers". Parliament.scot. Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Douglas Fraser (2 February 2016). "Scotland's tax powers: What it has and what's coming?". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Devolution Guidance Note 11 – Ministerial Accountability after Devolutio" (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. November 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "How the Scottish Parliament Works". gov.scot. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ "Government of Wales Act 2006".

- ^ "Government of Wales Act 2006, Schedule 5 (as amended)". Archived from the original on 20 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Scotland Act 1998: Schedule 5", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1998 c. 46 (sch. 5)

- ^ a b "Government of Wales Act 2006: Schedule 7A", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2006 c. 32 (sch. 7A)

- ^ The Secretary of State's veto and the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill (Report). 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Hillsborough Castle Agreement 2010".

- ^ "The Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Amendment of Schedule 3) Order 2010", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 31 March 2010, SI 2010/977, retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "Government of Ireland Act 1920 (1920 c. 67), section 4: Legislative powers of Irish Parliaments (as enacted)". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Act 1998: Schedule 2", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 19 November 1998, 1998 c. 47 (sch. 2), retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "Northern Ireland Act 1998: Schedule 3", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 19 November 1998, 1998 c. 47 (sch. 3), retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "Policing and Justice motion, Northern ireland Assembly, 12 April 2010". Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972 (1972 c. 22), section 1: Exercise of executive and legislative powers in N.I. (as enacted)". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 (1973 c. 36), section 31: Abolition of Parliament of Northern Ireland (as enacted)". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "The Northern Ireland Assembly (Prorogation) Order 1974", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 29 May 1974, SI 1974/926, retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "Northern Ireland Act 1974 (1974 c. 28), section 1: Dissolution and prorogation of existing Assembly... (as enacted)". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "The Northern Ireland Assembly (Dissolution) Order 1975", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 18 March 1975, SI 1975/422, retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "The Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Commencement No. 5) Order 1999", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 30 November 1999, SI 1999/3209, retrieved 27 December 2023

- ^ "Northern Ireland Act 1998 (1998 c. 47), Part VIII: Miscellaneous". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

External links

[edit]Legislation

[edit]- Text of the Scotland Act 1998 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Government of Wales Act as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Government of Wales Act 2006 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

Official guidance (published by the Cabinet Office)

[edit]- Devolution Guidance

- Devolution settlement: Scotland

- Northern Ireland: What is Devolved?

- Wales: What is Devolved?

Analysis

[edit]

Devolved, reserved and excepted matters

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definitions and Legal Distinctions

Devolved matters refer to areas of legislative competence transferred from the Parliament of the United Kingdom to the devolved institutions in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, enabling those bodies to enact primary legislation on specified policy fields such as health, education, and local government.[7] This delegation occurs through primary UK legislation, with the Scottish Parliament empowered under the Scotland Act 1998 to legislate on all matters except those explicitly reserved, while the Senedd Cymru (Welsh Parliament) operates under a reserved powers model established by the Wales Act 2017, permitting laws on any subject not reserved to Westminster. In Northern Ireland, devolved powers are termed "transferred matters" under the Northern Ireland Act 1998, covering domains like agriculture and justice (post-2007 devolution of policing and justice powers), distinct from the excepted and reserved categories unique to that jurisdiction. Reserved matters constitute policy areas retained exclusively by the UK Parliament, preventing devolved legislatures from legislating thereon without Westminster's consent, thereby preserving national uniformity in fields like foreign affairs, defence, and macroeconomic policy.[14] In Scotland, these are enumerated in Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998, encompassing topics including the Crown, the Civil Service, financial and economic matters (e.g., fiscal, monetary, and economic policy), and aspects of social security beyond basic rates.[4] Wales adopted a similar reserved model via the Wales Act 2017, listing reservations in Schedule 7A such as the monarchy, international relations, and certain welfare benefits, shifting from the prior conferred powers framework to clarify boundaries and reduce legal disputes over competence. This asymmetry reflects pragmatic adaptations: Scotland's model assumes broad competence absent reservation, while Wales's emphasizes explicit exclusions to avoid interpretive challenges observed in earlier disputes, such as those under the Government of Wales Act 2006.[7] Excepted matters apply solely to Northern Ireland under Schedule 2 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, denoting a subset of powers permanently withheld from the Northern Ireland Assembly to safeguard core UK constitutional integrity, including the succession to the Crown, nationality, and international relations.[3] Unlike reserved matters elsewhere, excepted matters in Northern Ireland cannot be devolved without amending primary UK legislation, forming a rigid "sterile deck" of competences insulated from local variation.[2] Reserved matters in Northern Ireland, outlined in Schedule 3 of the same Act, occupy an intermediate status: not excepted but not fully transferred, covering items like firearms regulation and certain elections, which may be devolved via UK parliamentary order subject to cross-community consent in the Assembly.[15] This tripartite structure—excepted, reserved, transferred—arises from the Good Friday Agreement's emphasis on stability amid historical divisions, contrasting with the binary devolved/reserved dichotomy in Scotland and Wales, and underscores devolution's asymmetrical nature tailored to each territory's political context.[7]Asymmetrical Devolution and Its Rationale

Asymmetrical devolution in the United Kingdom denotes the non-uniform allocation of powers from the central Parliament to its nations, resulting in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland operating legislatures with disparate legislative competences, fiscal authorities, and institutional designs, while England lacks a dedicated national assembly and relies on Westminster or limited English regional bodies. Enacted via the Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, and Northern Ireland Act 1998—stemming from referendums in September 1997 (Scotland approving by 74.3% on a 60.4% turnout; Wales by 50.3% on 50.1% turnout) and May 1998 for Northern Ireland (71.1% approval)—these settlements devolve primary legislative powers to Scotland immediately, secondary powers initially to Wales (upgraded to primary after a March 2011 referendum with 63.5% support), and transferred powers to Northern Ireland under a power-sharing executive. This variance persists despite subsequent expansions, such as Scotland's partial income tax control under the Scotland Act 2016 and Wales's limited land transaction taxes via the Wales Act 2017, underscoring the UK's rejection of symmetrical federalism in favor of bespoke, evolvable arrangements under Westminster's sovereign authority.[7][16] The disparities reflect causal historical divergences in national incorporation and governance. Scotland's 1707 union preserved autonomous civil institutions—like its legal system, education framework, and Presbyterian Church—sustaining a distinct civic identity that intensified home rule advocacy, particularly amid 1970s oil-driven nationalism and Scottish National Party gains (11 Westminster seats in 1974). Wales, annexed via the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542 and governed as an English extension with cultural assimilation policies until the 1960s, generated milder autonomy demands, evidenced by narrower referendum support and initial devolution confined to executive functions. Northern Ireland's framework, rooted in the 1921 partition and suspended Stormont Parliament (imposed direct rule in 1972 amid civil unrest), prioritizes consociational stability per the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, devolving justice and policing (transferred 2007–2010) but entailing "excepted" constitutional matters irreducible to mere reservation lists, alongside mandatory cross-community vetoes to mitigate ethno-sectarian divides absent in Celtic devolutions.[7][16][12] This tailored asymmetry arose from pragmatic responses to localized pressures rather than ideological symmetry, enabling the UK to neutralize separatist threats—such as quelling Scottish independence momentum post-1979 referendum failure—without risking England's 84% population dominance destabilizing a quasi-federal equilibrium. Bilateral negotiations and incremental reforms, including fiscal enhancements for Scotland (e.g., 2012 Edinburgh Agreement prelude to 2014 independence vote) versus Wales's phased expansions tied to demonstrated capacity, underscore an evolutionary logic prioritizing stability and consent over uniformity; Westminster's retained supremacy facilitates adjustments, as affirmed by the Sewel Convention (enshrined in Scotland Act 2016 and Wales Act 2017), which conventionally bars interference in devolved areas without legislative consent, though legally non-binding. Critics from unionist perspectives argue this fosters "postcode lottery" disparities in policy outcomes, yet proponents cite enhanced regional responsiveness, with Scotland wielding authority over 70% of public spending devolved matters versus Wales's narrower remit.[7][16][17]Scottish Devolution Framework

Devolved Powers in Scotland

The Scottish Parliament holds legislative authority over devolved matters as defined primarily by the Scotland Act 1998, which grants it competence to enact laws applicable within Scotland on all subjects except those explicitly reserved to the UK Parliament. This framework empowers the Parliament to address a wide array of domestic policy areas, reflecting the asymmetrical nature of UK devolution where Scotland retains significant autonomy compared to other nations.[9] Key devolved powers include health and social care, encompassing the organization and delivery of NHS Scotland services, public health initiatives, and social work provisions.[9] Education and training fall under devolved control, covering nursery, primary, secondary, further, and higher education, as well as skills development and student awards.[9] Justice and home affairs are substantially devolved, including the civil and criminal justice systems, courts, prisons, prosecution, and policing, though certain aspects like national security remain reserved.[9] Additional areas of competence involve rural affairs such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and rural development; environment and natural heritage, including environmental protection and land use planning; housing and urban regeneration; local government structure and finance; and aspects of transport like roads, rail services within Scotland, and ferries.[9] Economic development, including some enterprise and tourism policies, along with fire and rescue services, food standards, and aspects of consumer protection, are also devolved.[9] Subsequent legislation has expanded these powers: the Scotland Act 2012 devolved the ability to set a Scottish rate of income tax and introduced borrowing powers for capital expenditure, effective from April 2017. The Scotland Act 2016 further transferred responsibilities for a range of welfare benefits, employment support programs, and the minimum unit pricing of alcohol, enhancing fiscal and social policy levers available to the Scottish Government. These devolved responsibilities are exercised through primary legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament, which has enacted over 300 Acts since its establishment in 1999.[18]Reserved Matters in Scotland

Reserved matters in Scotland comprise the specific policy areas and legislative competences explicitly withheld from the Scottish Parliament under the Scotland Act 1998, as detailed in Schedule 5, and thus remain the exclusive domain of the UK Parliament at Westminster.[4] This reservation model operates on the principle that all powers are devolved except those enumerated as reserved, ensuring uniformity in matters affecting the United Kingdom as a whole or involving international obligations.[9] The framework was established to preserve the integrity of the Union while granting Scotland autonomy over domestic affairs, with reservations primarily targeting areas like national security, economic stability, and cross-border consistency.[14] Schedule 5 is structured into Part I, covering general reservations such as the Constitution (including the Crown, Union, and UK Parliament sovereignty), political parties, foreign affairs (international relations and treaties), public service (Civil Service), defence (armed forces and realm protection), and treason.[19] Part II delineates specific reservations across Heads A through L, encompassing financial and economic matters (e.g., fiscal policy, currency, financial services); home affairs (e.g., immigration, elections to UK Parliament, firearms); trade and industry (e.g., competition, intellectual property, import/export controls); energy (e.g., electricity, nuclear energy); transport (e.g., rail, air, shipping); social security (e.g., benefits schemes, child support); regulation of professions; employment (e.g., rights, health and safety); health and medicines (e.g., xenotransplantation, embryology); media and culture (e.g., broadcasting); and miscellaneous (e.g., equal opportunities, time zones, outer space).[20] Within these heads, sub-exceptions exist; for instance, certain consumer protections or energy efficiency measures may fall to devolved competence if not conflicting with UK-wide standards.[20] Key examples of reserved matters include defence and national security, foreign policy and international trade, immigration and nationality, most taxation (except limited devolved elements like income tax rates under the Scotland Act 2016), social security benefits, and broadcasting.[9] Employment law, financial services regulation, and macroeconomic policy also remain reserved to maintain a single UK market and fiscal union.[14] Subsequent legislation has refined this list: the Scotland Act 2012 added reservations on Antarctica activities (Head L7), while the Scotland Act 2016 and post-Brexit adjustments via the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 repatriated and reserved certain former EU competences, such as state aid and aspects of product standards, to Westminster.[21] These modifications reflect evolving priorities, including the need for unified UK responses to global challenges, though disputes over boundaries—such as Sewel Convention consent requirements—have occasionally arisen when UK legislation encroaches on devolved areas.[14] The reservation of these matters underscores the asymmetrical nature of UK devolution, where Scotland's extensive devolved powers contrast with retained UK oversight in strategic domains, preventing fragmentation of sovereignty.[9] Legislative changes to Schedule 5 require UK Parliamentary approval via Orders in Council, as seen in amendments effective from 1 July 2012 for Antarctica and 2020 for state aid under the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020. This structure has endured since the Scottish Parliament's establishment on 1 July 1999, with the reserved corpus adapting minimally to address specific gaps rather than broad expansions.Historical Evolution of Scottish Powers

The legislative autonomy of Scotland was extinguished following the Acts of Union 1707, which united the parliaments of Scotland and England, transferring all sovereign powers to the Parliament of Great Britain while preserving certain distinct Scottish legal, religious, and educational institutions. For over two centuries, Scotland experienced administrative devolution through bodies like the Scottish Office, established in 1885 and headed by a Secretary of State from 1926, handling domestic policy implementation but lacking independent legislative authority.[22] This arrangement persisted amid periodic nationalist advocacy, intensified by the Scottish National Party's (SNP) electoral gains from the 1960s, which highlighted demands for greater self-governance without altering the unitary UK's constitutional framework.[22] The first modern attempt at legislative devolution came with the Scotland Act 1978, which proposed a unicameral assembly with limited powers over devolved matters like health and education, subject to a referendum requiring approval by 40% of the electorate.[23] The March 1979 referendum saw 51.6% vote yes on a 63.7% turnout, equating to 32.5% of the electorate—falling short of the threshold—leading to the Act's repeal and reinforcing Westminster's dominance.[23] Renewed momentum under the Labour government culminated in the September 1997 referendum, where 74.3% approved a Scottish Parliament and 63.5% endorsed tax-varying powers, paving the way for the Scotland Act 1998.[7] Receiving royal assent on 19 November 1998, the Act devolved legislative competence over areas including agriculture, justice, and local government, while reserving foreign affairs, defense, macroeconomic policy, and immigration to the UK Parliament; the Scottish Parliament convened on 1 July 1999 and held its first elections on 6 May 1999.[5] Post-1998 expansions reflected political negotiations and referendum outcomes. The Scotland Act 2012 devolved taxes on land transactions and waste disposal, alongside capital borrowing powers up to £2.2 billion for the Scottish Government.[24] Following the 2014 independence referendum—where 55.3% voted no on a 84.6% turnout—the Smith Commission proposed "the strongest devolution package possible," implemented via the Scotland Act 2016, which transferred control over income tax rates and bands (excluding the 50p top rate initially), partial welfare benefits like Universal Credit top-ups, and aspects of employment support, while affirming Westminster's supremacy and introducing intergovernmental consent mechanisms for certain policies.[8] [7] These changes increased fiscal responsibility, with Scotland raising about 20-25% of its budget by 2025, though disputes over reserved matters like broadcasting and energy persisted.[7]Welsh Devolution Framework

Devolved Powers in Wales

The devolved powers in Wales are exercised by Senedd Cymru (the Welsh Parliament) and the Welsh Government, encompassing legislative competence over most domestic policy areas under a reserved powers model established by the Wales Act 2017, which took effect on 1 April 2018.[25] This framework grants the Senedd authority to enact laws on any subject not explicitly reserved to the UK Parliament, shifting from the prior conferred powers model under the Government of Wales Act 2006.[26] The Welsh Government implements and administers these powers, with responsibilities funded primarily through a block grant from the UK Government, supplemented by devolved taxes such as land transaction tax and landfill disposals tax since 2018, and the ability to vary income tax rates (non-default rates exercisable from 2019 onward).[11] Key devolved areas include:- Health and social care: Full legislative and executive control over NHS Wales organization, service delivery, public health, and social services, including mental health and child protection.[27]

- Education and training: Powers over schools, further and higher education, teacher qualifications, curriculum, and lifelong learning programs.[27]

- Local government and housing: Regulation of local authorities, electoral arrangements for local elections, housing policy, and social housing provision.[27][28]

- Agriculture, forestry, and fisheries: Management of rural affairs, animal health, plant varieties, and inshore fisheries up to 12 nautical miles.[27]

- Environment and natural resources: Oversight of water quality, flood management, waste, air pollution, and national parks.[27]

- Economic development: Promotion of industry, skills, and tourism, though major infrastructure projects often involve UK coordination.[29]

- Transport: Responsibility for most public transport (e.g., buses, light rail), road safety, and ports, with exceptions for cross-border rail and aviation.[28]

- Welsh language and culture: Promotion and legal status of the Welsh language under the Welsh Language Measure 2011, integrated into broader cultural policy.[10]

Reserved Matters in Wales

The reserved matters in Wales are delineated in Schedule 7A to the Government of Wales Act 2006, as inserted and amended by the Wales Act 2017, which implemented a reserved powers model operative from 1 April 2018.[30][31] This framework devolves all legislative competence to the Senedd Cymru except for matters expressly reserved to the UK Parliament, providing a clearer boundary than the prior conferred powers model while accommodating exceptions for Wales-specific implementation.[6] Schedule 7A comprises Part 1 on general reservations, Part 2 on specific reservations by subject heads (A through N), and Part 3 on interpretive provisions, with numerous exceptions allowing Senedd legislation in ancillary or implementation contexts, such as local enforcement of reserved UK-wide standards. Part 1 enumerates general reservations encompassing foundational UK-wide structures: the constitution (including the Crown, succession, and the union of England and Wales); the civil service; political parties (registration, funding, and finances, excluding Senedd-specific payments); the single legal jurisdiction of England and Wales (courts, judges, and judicial proceedings, with limited exceptions for devolved tribunals and family matters); tribunals (except those operating solely in Wales); international relations, trade regulation, and development assistance; and defence of the realm, including armed forces and fortifications. These ensure uniformity in core sovereign functions, with the shared England-Wales legal system notably distinguishing Welsh devolution from Scotland's, where justice powers are devolved.[32] Part 2 specifies reservations by heads, each with sub-fields and tailored exceptions:- Head A: Financial and Economic Matters reserves fiscal, monetary, and economic policy; currency; financial services and markets; and dormant accounts, excluding devolved taxes like non-domestic rates.

- Head B: Home Affairs covers elections; immigration and nationality; national security; interception of communications; crime, policing, and public order; anti-social behaviour; modern slavery; prostitution; emergency powers; extradition; rehabilitation of offenders; criminal records; dangerous items; drugs and psychoactive substances; private security; entertainment licensing; alcohol; betting and lotteries; hunting; animal procedures; lieutenancies; and charities, with exceptions for Senedd prosecution of devolved offences.

- Head C: Trade and Industry includes business associations; insolvency; competition policy; intellectual property; import/export controls; consumer protection; product safety; weights and measures; telecommunications; postal services; research councils; industrial development; export assistance; water and sewerage; pubs regulation; Sunday trading; and harmful subsidies, permitting exceptions for Welsh food standards.

- Head D: Energy reserves electricity licensing; oil, gas, and coal extraction; nuclear energy; and energy conservation measures like efficiency standards.

- Head E: Transport encompasses road vehicle regulation; rail franchising; marine and air transport; and security protocols, with devolved scope for local bus subsidies.

- Head F: Social Security, Child Support, Pensions and Compensation retains UK-wide schemes for benefits, child maintenance, occupational pensions, and public compensation, excluding local social services funding.

- Head G: Professions reserves oversight of architects, auditors, health professionals, and veterinary surgeons, excepting social work regulation.

- Head H: Employment covers rights, industrial relations, training boards, and job support programs.

- Head J: Health, Safety and Medicines includes abortion; xenotransplantation; embryology and genetics; medicines authorization; welfare foods; and workplace safety standards.

- Head K: Media, Culture and Sport reserves broadcasting; public lending rights; indemnity schemes; tax-satisfaction property; and sports grounds safety.

- Head L: Justice largely retains the legal profession; legal aid; coroners; arbitration; mental capacity; data protection; information rights; public records; crime compensation; prisons; family law (except adoption); gender recognition; and civil registration, reflecting the integrated justice system.[32]

- Head M: Land and Agricultural Assets reserves land registration and certain development consents.

- Head N: Miscellaneous includes equal opportunities enforcement; weapons controls; Ordnance Survey; time regulation; space activities; Antarctica; and seabed mining.

Historical Evolution of Welsh Powers

The push for devolved governance in Wales emerged in the late 19th century with movements like Cymru Fydd, but substantive legislative efforts began in the 20th century amid growing demands for administrative autonomy from Westminster.[33] A 1979 referendum on creating an elected assembly with limited powers failed decisively, with 79.7% voting against on a 58.7% turnout, reflecting limited public support at the time.[34] The Government of Wales Act 1998, enacted following a narrow 1997 referendum approval (50.3% yes on 50.1% turnout), established the National Assembly for Wales effective 1 July 1999, transferring executive functions previously held by the Secretary of State for Wales in areas such as health, education, and economic development, but without primary legislative competence.[35] This initial "executive devolution" model confined the Assembly to secondary legislation under powers conferred by UK Acts of Parliament.[36] The Government of Wales Act 2006 reformed the structure by formally separating the legislative (Assembly) and executive (Welsh Assembly Government) branches and introducing "Measures of the National Assembly for Wales," which allowed conditional primary legislation within 20 specified fields upon UK parliamentary approval via legislative competence orders.[37] This enhanced the Assembly's capacity but retained a conferred powers framework, limiting autonomy compared to Scotland's model.[38] A 2011 referendum granted full primary law-making powers, with 63.5% voting yes on a 40.0% turnout, enabling the Assembly to enact "Acts of the National Assembly for Wales" directly within devolved areas without Westminster's pre-approval.[39] Subsequent legislation expanded fiscal powers: the Wales Act 2014 devolved authority over stamp duty land transactions and landfill disposal taxes, alongside limited borrowing capacity for the Welsh Government.[11] The Wales Act 2017 marked a pivotal shift to a reserved powers model, akin to Scotland's, where all powers are devolved except those explicitly reserved to Westminster, clarifying boundaries and devolving additional competencies including variation of income tax rates, Senedd election rules, and onshore petroleum licensing. This framework, effective from 2018, addressed ambiguities in the prior conferred model and facilitated further fiscal devolution, such as the introduction of Welsh rates of income tax via the Wales Act 2014 amendments.[6] By 2020, the Assembly was renamed Senedd Cymru/Welsh Parliament, reflecting its evolved legislative status, though core powers remained anchored in the 2017 settlement.[40]Northern Ireland Devolution Framework

Devolved (Transferred) Powers in Northern Ireland

The transferred powers in Northern Ireland, as defined under the Northern Ireland Act 1998, comprise all matters not explicitly designated as excepted (entrenched at Westminster) or reserved (provisionally devolved but subject to UK oversight). These powers were devolved to the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive upon the restoration of devolution on 2 December 1999, enabling local legislation and policy-making in domestic affairs.[41][13] The Assembly may enact primary legislation on transferred matters, subject to cross-community consent requirements for sensitive issues, while the Executive implements corresponding functions through departments.[2] Key transferred powers include health and social services, which encompass hospital management, public health policy, and social care provision; education, covering school curricula, teacher qualifications, and higher education funding; and agriculture, environment, and rural affairs, involving farming subsidies, environmental protection, and rural development initiatives.[2][13] Economic development, employment, and skills training fall under devolved competence, allowing policies on job creation, vocational training, and regional investment. Housing policy, including social housing allocation and planning regulations, is similarly managed locally.[2] Infrastructure powers extend to transport, roads, and public works, while finance covers budgetary allocation within devolved areas, though major taxation remains largely reserved. Policing and justice powers, initially reserved, were transferred to the Assembly on 12 April 2010 via the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Devolution of Policing and Justice Functions) Order 2010, granting authority over criminal law, courts, prisons, prosecution, and offender management.[2] This devolution enhanced local accountability but required safeguards like UK fallback powers in cases of executive failure.[42]| Department | Key Transferred Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Department of Health | Healthcare delivery, mental health services, elderly care[2] |

| Department of Education | Primary/secondary schooling, special needs education, universities[2] |

| Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs | Food standards, fisheries, waste management[2] |

| Department for the Economy | Trade promotion, energy policy, skills development[2] |

| Department for Communities | Housing, urban regeneration, sports[2] |

| Department of Justice | Courts administration, youth justice, legal aid |

Reserved Matters in Northern Ireland

Reserved matters in Northern Ireland are those specified in Schedule 3 to the Northern Ireland Act 1998, over which the UK Parliament holds primary legislative authority, while the Northern Ireland Assembly is generally prohibited from legislating without the Secretary of State's consent under section 6 of the Act.[41][43] Unlike excepted matters, which are permanently reserved to Westminster, reserved matters may be transferred to the Assembly via an order in council, provided there is cross-community support in the Assembly and the Secretary of State deems it appropriate following consultation.[41] This framework, established under the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement of 1998, allows for potential evolution of devolution while safeguarding UK-wide interests such as financial stability and national security.[2] The scope of reserved matters is detailed across 42 paragraphs in Schedule 3, covering diverse policy areas with specific exclusions to delineate boundaries.[15] Key categories include:- Criminal justice and security elements: Crime prevention and detection (e.g., under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 and National Crime Agency functions), firearms and explosives regulation (per the Firearms (Northern Ireland) Order 2004), public processions, and civil contingencies (Part 2 of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004).

- Economic and financial regulation: Financial services, markets, and pensions (e.g., under the Pension Schemes Act 1993), building societies and friendly societies, money laundering (per the Money Laundering Regulations 2017), anti-competitive practices, monopolies, mergers, intellectual property (excluding plant varieties), and the National Minimum Wage Act 1998.

- Trade and infrastructure: Import and export controls, navigation and merchant shipping (excluding harbours), civil aviation (excluding aerodromes), telecommunications, wireless telegraphy, and internet services.

- Social and health policy aspects: Vaccine Damage Payment Scheme, surrogacy arrangements (Surrogacy Arrangements Act 1985), human fertilisation and embryology (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990), human genetics, and xenotransplantation.

- Other technical and administrative areas: Postal services (Postal Services Act 2000), National Lottery, units of measurement, consumer safety for goods, technical standards, data protection (Data Protection Acts 1984 and 1998), and research councils (Science and Technology Act 1965).

Excepted Matters in Northern Ireland

Excepted matters in Northern Ireland refer to areas of legislative competence permanently reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, as specified in Schedule 2 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, which implemented the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. These matters cannot be transferred to the Northern Ireland Assembly without amending the primary legislation, distinguishing them from reserved matters that may be devolved via secondary legislation by the Secretary of State. The designation ensures that fundamental aspects of UK sovereignty, national security, and constitutional integrity remain centralized, reflecting the unique post-conflict framework where devolution is conditional and reversible.[3][2] The Act organizes excepted matters into categories such as the Crown (including succession and regency), the UK Parliament's composition and procedures, and certain financial provisions like coinage and national loans. Key examples include:- International relations: Encompassing treaties, diplomatic representation, and consular functions, though excluding certain pre-Brexit EU-related implementations that were temporarily treated as transferred.[13]

- Defence and armed forces: Covering military establishments, forces, and equipment within Northern Ireland.[2]

- National security and intelligence: Including the activities of agencies like MI5 and matters related to terrorism prevention.[13]

- Nationality, immigration, and asylum: Handling passports, citizenship, and border controls.[2]

- Elections: For the UK Parliament and, in procedural aspects, the Northern Ireland Assembly.[13]

- Constitutional matters: Such as the Union itself, dissolution of the Assembly, and appointments to reserved offices like the Lord Chancellor.[3]

Parity Principle and Unique Arrangements

The parity principle governs the administration of devolved social security and pensions in Northern Ireland, requiring equivalence with provisions in Great Britain to uphold fiscal unity and prevent disparities that could incentivize constitutional change. Originating as a policy convention under the 1921 Government of Ireland Act and reinforced through reciprocal arrangements, it ensures that benefits such as unemployment insurance, state pensions, and disability allowances mirror those across the UK, with Northern Ireland's contributions to the National Insurance Fund treated identically.[44][45] Section 87 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 codifies this by obligating the Secretary of State to secure parity through affirmative parliamentary instruments, allowing temporary divergences only with UK Treasury consent and corresponding block grant adjustments to offset costs. This constraint has historically limited the Northern Ireland Executive's policy flexibility; for example, in 2014, resistance to aligning with UK welfare reforms—intended to reduce expenditure by £1.5 billion annually—triggered a government collapse and prolonged impasse, resolved only via side deals preserving parity while mitigating impacts on vulnerable groups.[46][47] The principle extends beyond strict benefit mirroring to "super-parity" in public spending, where Northern Ireland receives higher per capita allocations—approximately 20-25% above UK averages in health and education—totaling an estimated £600-700 million surplus in 2020/21, justified by historical underdevelopment and security legacies but critiqued for fostering dependency without equivalent fiscal accountability. Such arrangements, funded via the Barnett formula-derived block grant of £12.7 billion for 2024/25, underscore causal links between parity and economic integration, as deviations risk Treasury clawbacks and undermine the UK's internal market cohesion.[48][49] Northern Ireland's devolution features unique power-sharing mechanisms absent in Scotland or Wales, mandating cross-community consent for executive formation and key decisions on transferred matters like health, education, and justice. The First Minister and deputy First Minister, jointly elected via parallel assembly votes, share veto powers, while ministerial portfolios are distributed proportionally using the d'Hondt method among unionist, nationalist, and other designations, ensuring no single community dominates devolved governance.[50][51] The petition of concern, invocable by 30 members of the 90-seat Assembly, blocks legislation or executive actions perceived to discriminate against one community, applied over 180 times since 1998, including on issues like welfare reform and same-sex marriage, though reformed in 2016 to require evidence of rights impacts. Complementing this, six North-South implementation bodies—covering areas such as food safety, tourism, and language—facilitate joint authority on devolved functions with the Republic of Ireland, requiring concurrent Executive and Irish ministerial approval, as established by the 1999 British-Irish Agreement. These treaty-backed structures, ratified internationally, embed interdependence in power exercise, distinguishing Northern Ireland's framework by balancing local autonomy with safeguards against majority rule and provisions for ongoing Anglo-Irish oversight via the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference on reserved and excepted matters during suspensions.[42][52][16]Comparative and Common Elements

Overlapping Devolved Powers Across Nations

The devolution frameworks for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland establish a shared baseline of devolved powers in several domestic policy domains, enabling each legislature—the Scottish Parliament, Senedd Cymru, and Northern Ireland Assembly—to enact laws and allocate resources independently. These overlapping competences, rooted in the Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, and Northern Ireland Act 1998 (as amended), primarily cover health and social care, education, housing, local government structures, and elements of transport and economic development.[17] This commonality fosters policy experimentation and divergence, such as differing approaches to healthcare funding or school curricula, while necessitating UK-wide coordination to avoid internal market disruptions.[53] Health services represent a core overlapping area, with each administration responsible for the National Health Service (NHS) operations, public health initiatives, and social care integration within its territory. For instance, Scotland devolved health powers fully under the 1998 Act, allowing the Scottish Government to eliminate prescription charges nationwide by April 2011; Wales followed suit for most prescriptions by 2001 and eliminated remaining charges in 2007; Northern Ireland maintains free prescriptions aligned with its transferred powers since 1999.[16] Education similarly overlaps, encompassing primary, secondary, and further education policy, including curriculum standards, teacher qualifications, and school funding—powers exercised since devolution's inception, resulting in distinct systems like Scotland's Curriculum for Excellence introduced in 2010.[17] Housing and local government also feature prominently, with devolved authority over planning permissions, social housing provision, and municipal organization. Each nation manages affordable housing targets independently; for example, Wales legislated rent controls for social landlords via the Renting Homes (Wales) Act 2016, while Scotland enacted the Housing (Scotland) Act 2014 for similar reforms. Transport powers overlap in areas like road infrastructure and public passenger services, though rail franchising remains partially reserved or coordinated UK-wide. Agriculture, forestry, and environmental regulation further align, with devolved control over rural affairs subject to post-Brexit common frameworks agreed between 2020 and 2023 to harmonize standards in 13 policy areas, including food labeling and animal health.[54] These overlaps, while promoting tailored governance, have amplified intergovernmental disputes, particularly over funding equivalence and regulatory alignment.[53]Overlapping Reserved and Excepted Powers

In the devolution frameworks of the United Kingdom, certain core powers are reserved to the Westminster Parliament in Scotland under Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998 and in Wales under Schedule 7A of the Government of Wales Act 2006 (as amended), while analogous matters are excepted from transfer to the Northern Ireland Assembly under Schedule 2 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, ensuring centralized control over matters essential to the integrity and external relations of the state.[4][30][3] These overlaps reflect a deliberate design to preserve UK-wide sovereignty in areas where divergence could undermine national cohesion, such as constitutional fundamentals and security.[32] Prominent overlapping categories include:- Constitutional matters: Encompassing the Crown, its succession, the Union, and the sovereignty of the UK Parliament, which are explicitly reserved in Scotland (Part I of Schedule 5) and Wales (Part 1 of Schedule 7A), and excepted in Northern Ireland (paragraphs 1-3 of Schedule 2).[19]

- Foreign affairs and international relations: Reserved across all three (Scotland: Part V; Wales: paragraph 10 of Schedule 7A; Northern Ireland: paragraph 7 of Schedule 2), prohibiting devolved bodies from conducting diplomacy or treaties.

- Defence and armed forces: Centralized under Westminster in Scotland (Part I), Wales (paragraph 11 of Schedule 7A), and excepted in Northern Ireland (paragraph 8 of Schedule 2), covering the raising and deployment of UK forces.[19]

- National security and intelligence: Reserved in Scotland (Part I) and Wales (paragraphs 12-13 of Schedule 7A), overlapping with Northern Ireland's exceptions for national security (paragraph 9 of Schedule 2).[19]

- Immigration, nationality, and passports: Handled nationally, reserved in Scotland (Part II of Schedule 5, head D3), Wales (paragraph 14 of Schedule 7A), and excepted in Northern Ireland (paragraph 10 of Schedule 2).