Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

View on Wikipedia

| Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Duloxetine, an example of an SNRI. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Selective Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SNaRI |

| Use | Depression; Anxiety; Pain; Obesity; Menopausal symptoms |

| Biological target | Serotonin transporter; Norepinephrine transporter |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D000068760 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of antidepressant medications used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, social phobia, chronic neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), and menopausal symptoms. Off-label uses include treatments for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[1] SNRIs are monoamine reuptake inhibitors; specifically, they inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters are thought to play an important role in mood regulation. SNRIs can be contrasted with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), which act upon single neurotransmitters.[2]

The human serotonin transporter (SERT) and noradrenaline transporter (NAT) are membrane transport proteins that are responsible for the reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic nerve terminal. Dual inhibition of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake can offer advantages over other antidepressant drugs by treating a wider range of symptoms.[3] They can be especially useful in concomitant chronic or neuropathic pain.[4]

SNRIs, along with SSRIs and NRIs, are second-generation antidepressants. Since their introduction in the late 1980s, second-generation antidepressants have largely replaced first-generation antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), as the drugs of choice for the treatment of MDD due to their improved tolerability and safety profile.[5]

Medications

[edit]

There are eight FDA approved SNRIs in the United States, with venlafaxine being the first drug to be developed in 1993 and levomilnacipran being the latest drug to be developed in 2013. The drugs vary by their other medical uses, chemical structure, adverse effects, and efficacy.[6]

| Medication | Brand name | FDA Indications | Approval Year | Chemical structure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desvenlafaxine[7] | Pristiq

Khedezla (ER) |

|

2007 |  |

The active metabolite of venlafaxine. It is believed to work in a similar manner, though some evidence suggests lower response rates compared to venlafaxine and duloxetine. It was introduced by Wyeth in May 2008 and was then the third approved SNRI.[8] |

| Duloxetine[9] | Cymbalta

Irenka |

|

2004 |  |

Approved for the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain in August 2004. Duloxetine is contraindicated in patients with heavy alcohol use or chronic liver disease, as duloxetine can increase the levels of certain liver enzymes that can lead to acute hepatitis or other diseases in certain at risk patients. The risk of liver damage appears to be only for patients already at risk, unlike the antidepressant nefazodone, which, though rare, can spontaneously cause liver failure in healthy patients.[13] Duloxetine is also approved for major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), diabetic neuropathy, chronic musculoskeletal pain, including chronic osteoarthritis pain and chronic low back pain.[11] Duloxetine also undergoes hepatic metabolism and has been shown to cause inhibition of the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP 2D6.[14] Caution should be taken when taking Duloxetine with other medications that are metabolized by CYP 2D6 as this may precipitate a potential drug-drug interaction.[14] |

| Levomilnacipran | Fetzima |

|

2013 |  |

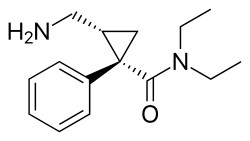

The levorotating isomer of milnacipran. Under development for the treatment of depression in the United States and Canada, it was approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD in July 2013. |

| Milnacipran | Ixel Savella Impulsor |

|

1996 |  |

Shown to be significantly effective in the treatment of depression and fibromyalgia.[15] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia in the United States in January 2009, however it is not approved for depression in that country.[citation needed] Milnacipran has been commercially available in Europe and Asia for several years.[citation needed] It was first introduced in France in 1996.[citation needed] |

| Sibutramine | Meridia | 1997 |  |

An SNRI, which, instead of being developed for the treatment of depression, was widely marketed as an appetite suppressant for weight loss purposes. Sibutramine was the first drug for the treatment of obesity to be approved in 30 years.[17] It has been associated with increased cardiovascular events and strokes and has been withdrawn from the market in several countries and regions including the United States in 2010.[18] | |

| Tramadol | Ultram |

|

1977 |  |

A dual weak opioid and SNRI. It was approved by the FDA in 1995, though it has been marketed in Germany since 1977. The drug is used to treat acute and chronic pain. It has shown effectiveness in the treatment of fibromyalgia, though it is not specifically approved for this purpose. The drug is also under investigation as an antidepressant and for the treatment of neuropathic pain. It is related in chemical structure to venlafaxine. Due to being an opioid, there is risk of abuse and addiction, but it does have less abuse potential, respiratory depression, and constipation compared to other opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone, etc.).[19] |

| Venlafaxine | Effexor | 1994 |  |

The first and most commonly used SNRI. It was introduced by Wyeth in 1994. The reuptake effects of venlafaxine are dose-dependent. At low doses (<150 mg/day), it acts only on serotonergic transmission. At moderate doses (>150 mg/day), it acts on serotonergic and noradrenergic systems, whereas at high doses (>300 mg/day), it also affects dopaminergic neurotransmission.[22] At small doses, venlafaxine has also been shown to be effective in treating vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) of menopause.[21] |

History

[edit]In 1952, iproniazid, an antimycobacterial agent, was discovered to have psychoactive properties while researched as a possible treatment for tuberculosis. Researchers noted that patients given iproniazid became cheerful, more optimistic, and more physically active. Soon after its development, iproniazid and related substances were shown to slow enzymatic breakdown of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine via inhibition of the enzyme monoamine oxidase. For this reason, this class of drugs became known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or MAOIs. During this time development of distinctively different antidepressant agents was also researched. Imipramine became the first clinically useful tricyclic antidepressant (TCA). Imipramine was found to affect numerous neurotransmitter systems and to block the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin from the synapse, therefore increasing the levels of these neurotransmitters. Use of MAOIs and TCAs gave major advances in treatment of depression but their use was limited by unpleasant side effects and significant safety and toxicity issues.[23]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the catecholamine hypothesis of emotion and its relation to depression was of wide interest and that the decreased levels of certain neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine might play a role in the pathogenesis of depression. This led to the development of fluoxetine, the first SSRI. The improved safety and tolerability profile of the SSRIs in patients with MDD, compared with TCAs and MAOIs, represented yet another important advance in the treatment of depression.[23]

Since the late 1980s, SSRIs have dominated the antidepressant drug market. Today, there is increased interest in antidepressant drugs with broader mechanisms of action that may offer improvements in efficacy and tolerability. In 1993, a new drug was introduced to the US market called venlafaxine, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.[20] Venlafaxine was the first compound described in a new class of antidepressant substances called phenylethylamines. These substances are unrelated to TCA and other SSRIs. Venlafaxine blocks the neuronal reuptake of serotonin, noradrenaline and, to a lesser extent, dopamine in the central nervous system. In contrast with several other antidepressant drugs, venlafaxine can induce a rapid onset of action mainly due to a subsequent norepinephrine reuptake inhibition.[24] See timeline in figure 1.

Mechanism of action

[edit]Monoamines are connected to the pathophysiology of depression. Symptoms may occur because concentrations of neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, are insufficient, leading to downstream changes.[10][25] Medications for depression affect the transmission of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.[10] Older and less selective antidepressants like TCAs and MAOIs inhibit the reuptake or metabolism of norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain, which results in higher concentrations of neurotransmitters.[25] Antidepressants that have dual mechanisms of action inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine and, in some cases, inhibit with weak effect the reuptake of dopamine.[10] Antidepressants affect variable neuronal receptors such as muscarinic cholinergic, α1- and α2-adrenergic, H1-histaminergic, and sodium channels in the cardiac muscle, leading to decreased cardiac conduction and cardiotoxicity associated particularly with TCAs, and to a lesser extent with SSRIs.[26] Selectivity of antidepressant agents are based on the neurotransmitters that are thought to influence symptoms of depression.[27] Drugs that selectively block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine effectively treat depression and are better tolerated than TCAs. TCAs have comprehensive effects on various neurotransmitters receptors, which leads to lack of tolerability and increased risk of toxicity.[2]

Tricyclic antidepressants

[edit]

TCAs were the first medications that had dual mechanism of action. The mechanism of action of tricyclic secondary amine antidepressants is only partly understood. TCAs have dual inhibition effects on norepinephrine reuptake transporters and serotonin reuptake transporters. Increased norepinephrine and serotonin concentrations are obtained by inhibiting both of these transporter proteins. TCAs have substantially more affinity for norepinephrine reuptake proteins than the SSRIs. This is because of a formation of secondary amine TCA metabolites.[28][29]

In addition, the TCAs interact with adrenergic receptors. This interaction seems to be critical for increased availability of norepinephrine in or near the synaptic clefts. Actions of imipramine-like tricyclic antidepressants have complex, secondary adaptions to their initial and sustained actions as inhibitors of norepinephrine transport and variable blockade of serotonin transport.

Norepinephrine interacts with postsynaptic α and β adrenergic receptor subtypes and presynaptic α2 autoreceptors. The α2 receptors include presynaptic autoreceptors which limit the neurophysiological activity of noradrenergic neurons in the central nervous system. Formation of norepinephrine is reduced by autoreceptors through the rate-limiting enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, an effect mediated by decreased cyclic AMP-mediated phosphorylation-activation of the enzyme.[29] α2 receptors also cause decreased intracellular cyclic AMP expression which results in smooth muscle relaxation or decreased secretion.[30]

TCAs activate a negative feedback mechanism through their effects on presynaptic receptors. One probable explanation for the effects on decreased neurotransmitter release is that, as the receptors activate, inhibition of neurotransmitter release occurs (including suppression of voltage-gated Ca2+ currents and activation of G protein-coupled receptor-operated K+ currents). Repeated exposure of agents with this type of mechanism leads to inhibition of neurotransmitter release, but repeated administration of TCAs finally leads to decreased responses by α2 receptors. The desensitization of these responses may be due to increased exposure to endogenous norepinephrine or from the prolonged occupation of the norepinephrine transport mechanisms (via an allosteric effect). The adaptation allows the presynaptic synthesis and secretion of norepinephrine to return to, or even exceed, normal levels of norepinephrine in the synaptic clefts. Overall, inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake induced by TCAs leads to decreased rates of neuron firing (mediated through α2 autoreceptors), metabolic activity, and release of neurotransmitters.[29]

TCAs do not block dopamine transport directly but might facilitate dopaminergic effects indirectly by inhibiting dopamine transport into noradrenergic terminals of the cerebral cortex.[29] Because they affect so many different receptors, TCAs have adverse effects, poor tolerability, and an increased risk of toxicity.[2]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

[edit]Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) selectively inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and are a widely used group of antidepressants.[31] With increased receptor selectivity compared to TCAs, undesired effects such as poor tolerability are avoided.[29] Serotonin is synthesized from an amino acid called L-tryptophan. Active transport system regulates the uptake of tryptophan across the blood–brain barrier. Serotonergic pathways are classified into two main ways in the brain: the ascending projections from the medial and dorsal raphe and the descending projections from the caudal raphe into the spinal cord.

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

[edit]Noradrenergic neurons are located in two major regions in the brain, the locus coeruleus and lateral tegmental. With administration of SNRIs, neuronal activity in the locus coeruleus is induced because of increased concentration of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft. This results in activation of α2 adrenergic receptors,[25] as discussed previously.

Assays have shown that SNRIs have insignificant penchant for mACh, α1 and α2 adrenergic, or H1 receptors.[27]

Dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

[edit]Agents with dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (SNRIs) are sometimes called non-tricyclic serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Clinical studies suggest that compounds that increase the concentration in the synaptic cleft of both norepinephrine and serotonin are more successful than single acting agents in the treatment of depression, but the data is not conclusive whether SNRIs are a more effective treatment option over SSRIs for depression.[32][33][34]

The non-tricyclic SNRIs have several important differences that are based on pharmacokinetics, metabolism to active metabolites, inhibition of CYP isoforms, effect of drug-drug interactions, and the half-life of the nontricyclic SNRIs.[28][35]

Combination of mechanisms of action in a single active agent is an important development in psychopharmacology.[35]

Structure activity relationship

[edit]Aryloxypropanamine scaffold

[edit]Several reuptake inhibitors contain an aryloxypropanamine scaffold. This structural motif has potential for high affinity binding to biogenic amine transports.[35] Drugs containing an aryloxypropanamine scaffold have selectivity profile for norepinephrine and serotonin transporters that depends on the substitution pattern of the aryloxy ring. Selective NRIs contain a substituent in 2' position of the aryloxy ring but SSRIs contain a substituent in 4' position of the aryloxy ring. Atomoxetine, nisoxetine and reboxetine all have a substitution group in the 2' position and are selective NRIs while compounds that have a substitution group in the 4' position (like fluoxetine and paroxetine) are SSRIs. Duloxetine contains a phenyl group fused at the 2' and 3' positions, therefore it has dual selective norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitory effects and has similar potencies for both transporters.[36] The nature of the aromatic substituent also has a significant influence on the activity and selectivity of the compounds as inhibitors of the serotonin or the norepinephrine transporters.[35]

Cycloalkanol ethylamine scaffold

[edit]Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine contain a cycloalkanol ethylamine scaffold. Increasing the electron-withdrawing nature of the aromatic ring provides a more potent inhibitory effect of norepinephrine uptake and improves the selectivity for norepinephrine over the serotonin transporter.[36] Effects of chloro, methoxy and trifluoromethyl substituents in the aromatic ring of cycloalkanol ethylamine scaffold were tested. The results showed that the strongest electron-withdrawing m-trifluoromethyl analogue exhibited the most potent inhibitory effect of norepinephrine and the most selectivity over serotonin uptake.[36] WY-46824, a piperazine-containing derivative, has shown norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibition. Further synthesis and testing identified WAY-256805, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that exhibited excellent selectivity and was efficacious in animal models of depression, pain, and thermoregulatory dysfunction.[37]

Milnacipran

[edit]

Milnacipran is structurally different from other SNRIs.[28] The structure activity relationship of milnacipran derivatives at the transporter level is still largely unclear and is based on in vivo efficacy that was reported in 1987. N-methylation of milnacipran in substituent group R4 and R5 reduces the norepinephrine and serotonin activity.[38] Researches on different secondary amides in substitution groups R6 and R7 showed that π electrons play an important role in the interaction between transporters and ligands. A phenyl group in substituent R6 showed effect on norepinephrine transporters. Substituent groups in R6 and R7 with allylic double bond showed significant improved effect on both norepinephrine and serotonin transporters.[38] Studies show that introducing a 2-methyl group in substituent R3, the potency at norepinephrine and serotonin transporters are almost abolished. Methyl groups in substituent groups R1 and R2 also abolish the potency at norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. Researchers found that replacing one of the ethyl groups of milnacipran with an allyl moiety increases the norepinephrine potency.[39] The pharmacophore of milnacipran derivatives is still largely unclear.[38]

The conformation of milnacipran is an important part of its pharmacophore. Changing its stereochemistry affects the norepinephrine and serotonin concentration. Milnacipran is marketed as a racemic mixture. Effects of milnacipran reside in the (1S,2R)-isomer and substitution of the phenyl group in the (1S,2R)-isomer has negative impact on norepinephrine concentration.[39] Milnacipran has low molecular weight and low lipophilicity. Because of these properties, milnacipran exhibits almost ideal pharmacokinetics in humans such as high bioavailability, low inter-subject variability, limited liver enzyme interaction, moderate tissue distribution and a reasonably long elimination half-life. Milnacipran's lack of drug-drug interactions via cytochrome P450 enzymes is thought to be an attractive feature because many of the central nervous system drugs are highly lipophilic and are mainly eliminated by liver enzymes.[39]

Future development of structure activity relationship

[edit]The application of an aryloxypropanamine scaffold has generated a number of potent MAOIs.[40] Before the development of duloxetine, the exploration of aryloxypropanamine structure activity relationships resulted in the identification of fluoxetine and atomoxetine. The same motif can be found in reboxetine where it is constrained in a morpholine ring system. Some studies have been made where the oxygen in reboxetine is replaced by sulfur to give arylthiomethyl morpholine. Some of the arylthiomethyl morpholine derivatives maintain potent levels of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition resides in different enantiomers for arylthiomethyl morpholine scaffold.[41] Possible drug candidates with dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitory activity have also been derived from piperazine, 3-amino-pyrrolidine and benzylamine templates.[42]

Clinical trials

[edit]Depression

[edit]Several studies have shown that antidepressant drugs which have combined serotonergic and noradrenergic activity are generally more effective than SSRIs, which act upon serotonin reuptake by itself. Serotonergic-noradrenergic antidepressant drugs may have a modest efficacy advantage compared to SSRIs in treating major depressive disorder (MDD),[43] but are slightly less well tolerated.[44] Further research is needed to examine the possible differences of efficacy in specific MDD sub-populations or for specific MDD symptoms, between these classes of antidepressant drugs.

Analgesic

[edit]Data from clinical trials have indicated that SNRIs might have pain relieving properties. Although the perception and transmission of pain stimuli in the central nervous system have not been fully elucidated, extensive data support a role for serotonin and norepinephrine in the modulation of pain. Findings from clinical trials in humans have shown these antidepressants can help to reduce pain and functional impairment in central and neuropathic pain conditions. This property of SNRIs might be used to reduce doses of other pain relieving medication and lower the frequency of safety, limited efficacy and tolerability issues.[45] Clinical research data have shown in patients with GAD that the SNRI duloxetine is significantly more effective than placebo in reducing pain-related symptoms of GAD, after short-term and long-term treatment. However, findings suggested that such symptoms of physical pain reoccur in relapse situations, which indicates a need for ongoing treatment in patients with GAD and concurrent painful physical symptoms.[46]

Indications

[edit]SNRIs have been tested for treatment of the following conditions:

Pharmacology

[edit]Route of administration

[edit]

SNRIs are delivered orally, usually in the form of capsules or tablets. It is recommended to take SNRIs in the morning with breakfast, which does not affect drug levels, but may help with certain side effects.[48] Norepinephrine has activating effects in the body and therefore can cause insomnia in some patients if taken at bedtime.[49] SNRIs can also cause nausea, which is usually mild and goes away within a few weeks of treatment, but taking the medication with food can help alleviate this.[50]

Mode of action

[edit]The condition for which SNRIs are mostly indicated, major depressive disorder, was thought to be mainly caused by decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft, causing erratic signaling. This theory, however, has been refuted.[51] Based on the monoamine hypothesis of depression, which asserts that decreased concentrations of monoamine neurotransmitters leads to depressive symptoms, the following relations were determined: "Norepinephrine may be related to alertness and energy as well as anxiety, attention, and interest in life; [lack of] serotonin to anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions; and dopamine to attention, motivation, pleasure, and reward, as well as interest in life."[52] SNRIs work by inhibiting the reuptake of the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine. This results in increased extracellular concentrations of serotonin and norepinephrine and, consequently, an increase in neurotransmission. Most SNRIs including venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine, are several fold more selective for serotonin over norepinephrine, while milnacipran is three times more selective for norepinephrine than serotonin. Elevation of norepinephrine levels is thought to be necessary for an antidepressant to be effective against neuropathic pain, a property shared with the older tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but not with the SSRIs.[53]

Recent studies have shown that depression may be linked to increased inflammatory response,[54] thus attempts at finding an additional mechanism for SNRIs have been made. Studies have shown that SNRIs as well as SSRIs have significant anti-inflammatory action on microglia[55] in addition to their effect on serotonin and norepinephrine levels. As such, it is possible that an additional mechanism of these drugs that acts in combination with the previously understood mechanism exist. The implication behind these findings suggests use of SNRIs as potential anti-inflammatories following brain injury or any other disease where swelling of the brain is an issue. However, regardless of the mechanism, the efficacy of these drugs in treating the diseases for which they have been indicated has been proven, both clinically and in practice.[improper synthesis?]

Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Most SNRIs function alongside primary metabolites and secondary metabolites in order to inhibit reuptake of serotonin, norepinepherine, and marginal amounts of dopamine. For example, venlafaxine works alongside its primary metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine to strongly inhibit serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the brain. The evidence also suggests that dopamine and norepinephrine behave in a co-transportational manner, due to the inactivation of dopamine by norepinephrine reuptake in the frontal cortex, an area of the brain largely lacking in dopamine transporters. This effect of SNRIs results in increased dopamine neurotransmission, in addition to the increases in serotonin and norepinephrine activity.[56] Furthermore, because SNRIs are extremely selective, they have no measurable effects on other, unintended receptors, in contrast to monoamine oxidase inhibition.[57] Pharmaceutical tests have determined that use of both SNRIs or SSRIs can generate significant anti-inflammatory action on microglia, as well.[55][16][58][59][11][60]

Activity profiles

[edit]| Compound | SERT | NET | ~Ratio (5-HT : NE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki | IC50 | Ki | IC50 | ||

| Venlafaxine | 7.8 | 145 | 1920 | 1420 | ~30:1 |

| Desvenlafaxine | 40.2 | 47.3 | 558.4 | 531.3 | 11.2:1 |

| Duloxetine | 0.07 | 3.7 | 1.17 | 20 | 5.4:1 |

| Atomoxetine | 87[62] | 5.4[62] | 0.06:1 (= 1:16) | ||

| Milnacipran | 8.44 | 151 | 22 | 68 | 2:1[64] |

| Levomilnacipran | 11.2 | 19.0 | 92.2 | 10.5 | 0.55:1 (= 1:1.8) |

| All of the Ki and IC50 values are nM. The 5-HT/NE ratio is based on IC50 values for the SERT and NET.[61] | |||||

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The half-life of venlafaxine is about 5 hours, and with once-daily dosing, steady-state concentration is achieved after about 3 days, though its active metabolite desvenlafaxine lasts longer.[59] The half-life of desvenlafaxine is about 11 hours, and steady-state concentrations are achieved after 4 to 5 days.[58] The half-life of duloxetine is about 12 hours (range: 8–17 hours), and steady-state is achieved after about 3 days.[11] Milnacipran has a half-life of about 6 to 8 hours, and steady-state levels are reached within 36 to 48 hours.[60]

Contraindications

[edit]SNRIs are contraindicated in patients taking MAOIs within the last two weeks due to the increased risk of serotonin syndrome, which can be life-threatening.[65] Other drugs and substances that should be avoided due to increased risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with an SNRI include: other anti-depressants, anti-convulsants, analgesics, antiemetic agents, anti-migraine medications, methylene blue, linezolid, Lithium, St. John's wort, ecstasy, and LSD.[65] Signs and symptoms of serotonin syndrome include: hyperthermia, rigidity, myoclonus, autonomic instability with fluctuating vital signs, and mental status changes that include extreme agitation progressing to delirium and coma.[11]

Due to the effects of increased norepinephrine levels and, therefore, higher noradrenergic activity, pre-existing hypertension should be controlled before treatment with SNRIs and blood pressure periodically monitored throughout treatment.[66] Duloxetine has also been associated with cases of liver failure and should not be prescribed to patients with chronic alcohol use or liver disease. Studies have found that Duloxetine can increase liver function tests three times above their upper normal limit.[67] Patients with coronary artery disease should caution the use of SNRIs.[68] Furthermore, due to some SNRIs' actions on obesity, patients with major eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia should not be prescribed SNRIs.[16] Duloxetine and milnacipran are also contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, as they have been shown to increase incidence of mydriasis.[11][60]

SNRIs should not be used to treat depressive episodes in Bipolar disorder I and should only be used to treat depression in Bipolar disorder II with caution and accompanied by mood stabilizers to avoid hypomania.[69]

Side effects

[edit]Since SNRIs and SSRIs act in similar ways to elevate serotonin levels, they share many side effects, though to varying degrees. Some common side effects include nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, sweating, increased blood pressure, loss of appetite, headache, increase in suicidal thoughts, and sexual dysfunction.[70] Elevation of norepinephrine levels can sometimes cause anxiety, mildly elevated pulse, and elevated blood pressure. However, norepinephrine-selective antidepressants, such as reboxetine and desipramine, have successfully treated anxiety disorders.[71] People at risk for hypertension and heart disease should monitor their blood pressure.[16][58][59][11][60]

Sexual Dysfunction

[edit]SNRIs, similarly to SSRIs, can cause several types of sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, sexual anhedonia, and anorgasmia.[11][59][72] The two common sexual side effects are diminished interest in sex (libido) and difficulty reaching climax (anorgasmia), which are usually somewhat milder with SNRIs compared to SSRIs.[73] To manage sexual dysfunction, studies have shown that switching to or augmenting with bupropion or adding a PDE5 Inhibitor have decreased symptoms of sexual dysfunction.[74] Studies have shown that PDE5 Inhibitors, such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), vardenafil (Levitra), and avanafil (Stendra), have sometimes been helpful to decrease the sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction, although they have been shown to be more effective in men than women.[74]

Serotonin Syndrome

[edit]A serious, but rare, side effect of SNRIs is serotonin syndrome, which is caused by an excess of serotonin in the body. Serotonin syndrome can be caused by taking multiple serotonergic drugs, such as SSRIs or SNRIs. Other drugs that contribute to serotonin syndrome include MAO inhibitors, linezolid, tedizolid, methylene blue, procarbazine, amphetamines, clomipramine, and more.[75] Early symptoms of serotonin syndrome may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, agitation, confusion, muscle rigidity, dilated pupils, hyperthermia, rigidity, and goose bumps. More severe symptoms include fever, seizures, irregular heartbeat, delirium, and coma.[76][77][11] If signs or symptoms arise, discontinue treatment with serotonergic agents immediately.[76] It is recommended to washout 4 to 5 half-lives of the serotonergic agent before using an MAO inhibitor.[78]

Bleeding

[edit]Some studies suggest there are risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, especially venlafaxine, due to impairment of platelet aggregation and depletion of platelet serotonin levels.[79][80] Similarly to SSRIs, SNRIs may interact with anticoagulants, like warfarin. There is more evidence of SSRIs having higher risk of bleeding than SNRIs.[79] Studies have suggested caution when using SNRIs or SSRIs with high doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen due to an increased risk of upper GI bleeding.[34]

Visual problems

[edit]

Similarly to other antidepressants, SNRI medications have been found to cause visual snow syndrome, a condition characterized by visual static, palinopsia (negative after image), nyctalopia (poor vision at night), and photophobia (brighter presentation of lights or highlighted colors). Evidence shows that 8.9% of those taking SNRIs experienced visual snow, 10.5% experienced palinopsia, 15.3% experienced photophobia, and 17.7% experienced nyctolopia as the result of SNRI prescription intake. Amitriptyline, and citalopram have also been reported to worsen or cause symptoms of VSS.[81]

Precautions

[edit]Starting an SNRI regimen

[edit]Due to the extreme changes in noradrenergic activity produced from norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition, patients that are just starting an SNRI regimen are usually given lower doses than their expected final dosing to allow the body to acclimate to the drug's effects. As the patient continues along at low doses without any side-effects, the dose is incrementally increased until the patient sees improvement in symptoms without detrimental side-effects.[82]

Discontinuation syndrome

[edit]As with SSRIs, the abrupt discontinuation of an SNRI usually leads to withdrawal, or "discontinuation syndrome", which could include states of anxiety and other symptoms. Therefore, it is recommended that users seeking to discontinue an SNRI slowly taper the dose under the supervision of a professional. Discontinuation syndrome has been reported to be markedly worse for venlafaxine when compared to other SNRIs. As such, as tramadol is related to venlafaxine, the same conditions apply.[83] This is likely due to venlafaxine's relatively short half-life and therefore rapid clearance upon discontinuation. In some cases, switching from venlafaxine to fluoxetine, a long-acting SSRI, and then tapering off fluoxetine, may be recommended to reduce discontinuation symptoms.[84][85] Signs and symptoms of withdrawal from abrupt cessation of an SNRI include dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, nausea, sweating, and flu-like symptoms, such as lethargy and malaise.[85]

Overdose

[edit]Causes

[edit]Overdosing on SNRIs can be caused by either drug combinations or excessive amounts of the drug itself. Venlafaxine is marginally more toxic in overdose than duloxetine or the SSRIs.[16][58][59][11][60][86]

Symptoms

[edit]Symptoms of SNRI overdose, whether it be a mixed drug interaction or the drug alone, vary in intensity and incidence based on the amount of medicine taken and the individuals sensitivity to SNRI treatment. Possible symptoms may include:[11]

- Somnolence

- Coma

- Serotonin syndrome

- Seizures

- Syncope

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Hypertension

- Hyperthermia

- Vomiting

Management

[edit]Overdose is usually treated symptomatically, especially in the case of serotonin syndrome, which requires treatment with cyproheptadine and temperature control based on the progression of the serotonin toxicity.[87] Patients are often monitored for vitals and airways cleared to ensure that they are receiving adequate levels of oxygen. Another option is to use activated carbon in the GI tract in order to absorb excess neurotransmitter.[11]

Comparison to SSRIs

[edit]Because SNRIs were developed more recently than SSRIs, there are relatively few of them. However, the SNRIs are among the most widely used antidepressants today. In 2009, Cymbalta and Effexor were the 11th- and 12th-most-prescribed branded drugs in the United States, respectively. This translates to the 2nd- and 3rd-most-common antidepressants, behind Lexapro (escitalopram), an SSRI.[88] In some studies, SNRIs demonstrated slightly higher antidepressant efficacy than the SSRIs (response rates 63.6% versus 59.3%).[43] However, in one study escitalopram had a superior efficacy profile to venlafaxine.[89]

Special populations

[edit]Pregnancy

[edit]No antidepressants are FDA approved during pregnancy.[90][failed verification] Use of antidepressants during pregnancy may result in fetus abnormalities affecting functional development of the brain and behavior.[90][dubious – discuss] Studies have shown correlations between pregnant women treated with SNRIs and risk of hypertensive disorders,[91] preeclampsia,[92] miscarriage,[93] seizures in children,[94] and many other adverse affects.[citation needed]

Pediatrics

[edit]SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be effective in treating major depressive disorder and anxiety in pediatric populations.[95] However, differences in metabolism, renal function, and total percentage of body water and body fat can influence the pharmacokinetics of medications in youths as compared to adults.[96] Additionally, there is a risk of increased suicidality in pediatric populations for treatment of major depressive disorder, especially with venlafaxine.[95] Fluoxetine and Escitalopram are the only antidepressants that are approved for child/adolescent major depressive disorder.[96] A literature review by Castagna, et. al from 2023 shows indications of efficacy treating pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Currently, Duloxetine, an SNRI, is the only FDA-approved medication for pediatric GAD, despite the fact that SSRIs are typically first-line treatment.[96][97] It is suggested that these medications be combined with psychotherapy to maximize effectiveness.[98][96]

Geriatrics

[edit]Most antidepressants, including SNRIs, are safe and effective in the geriatric population. The geriatric population is at greater risk for adverse effects relating to drug interaction as they are more likely to experience polypharmacy.[99] Decisions are often based on co-morbid conditions, drug interactions, and patient tolerance. Due to differences in body composition and metabolism, starting doses are often half that of the recommended dose for younger adults.[100] Studies show that these factors also put the geriatric population at increased risk of adverse effects when treated with SNRIs but not with SSRIs.[101][102]

Research

[edit]A systematic review that looked at the efficacy of antidepressants for pain relief concludes that only 11 of 42 comparisons showed evidence of efficacy. Seven of the eleven comparisons belong to the SNRI drug class.[103]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cleveland Clinic medical professional (2023-03-05). "SNRIs". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2024-01-09.

- ^ a b c Stahl SM, Grady MM, Moret C, Briley M (September 2005). "SNRIs: their pharmacology, clinical efficacy, and tolerability in comparison with other classes of antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 10 (9): 732–747. doi:10.1017/S1092852900019726. PMID 16142213.

- ^ Cashman JR, Ghirmai S (October 2009). "Inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake and inhibition of phosphodiesterase by multi-target inhibitors as potential agents for depression". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 17 (19): 6890–6897. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.025. PMID 19740668.

- ^ Wright ME, Rizzolo D (March 2017). "An update on the pharmacologic management and treatment of neuropathic pain". JAAPA. 30 (3): 13–17. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000512228.23432.f7. PMID 28151738. S2CID 205396280.

- ^ Spina E, Santoro V, D'Arrigo C (July 2008). "Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update". Clinical Therapeutics. 30 (7): 1206–1227. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(08)80047-1. PMID 18691982.

- ^ Hillhouse TM, Porter JH (February 2015). "A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1037/a0038550. PMC 4428540. PMID 25643025.

- ^ a b Deecher DC, Beyer CE, Johnston G, Bray J, Shah S, Abou-Gharbia M, et al. (August 2006). "Desvenlafaxine succinate: A new serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 318 (2): 657–665. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.103382. PMID 16675639. S2CID 15063064.

- ^ a b Perry R, Cassagnol M (June 2009). "Desvenlafaxine: a new serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder". Clinical Therapeutics. 31 (1): 1374–1404. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.07.012. PMID 19698900.

- ^ Iyengar S, Webster AA, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Xu JY, Simmons RM (November 2004). "Efficacy of duloxetine, a potent and balanced serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in persistent pain models in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 311 (2): 576–584. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.070656. PMID 15254142. S2CID 18022449.

- ^ a b c d Hunziker ME, Suehs BT, Bettinger TL, Crismon ML (August 2005). "Duloxetine hydrochloride: a new dual-acting medication for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Clinical Therapeutics. 27 (8): 1126–1143. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.08.010. PMID 16199241.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Cymbalta- duloxetine hydrochloride capsule, delayed release". DailyMed. 20 September 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Yentreve (duloxetine hydrochloride) Hard Gastro-Resistant Capsules. Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Nefazodone hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b Frampton JE, Plosker GL (2007). "Duloxetine: a review of its use in the treatment of major depressive disorder". CNS Drugs. 21 (7): 581–609. doi:10.2165/00023210-200721070-00004. PMID 17579500. S2CID 22242897.

- ^ a b Morishita S, Arita S (February 2003). "The clinical use of milnacipran for depression". European Psychiatry. 18 (1): 34–35. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(02)00003-2. PMID 12648895. S2CID 5978467.

- ^ a b c d e "Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Capsules C-IV. Full Prescribing Information (archived label)". Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL 60064, USA. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Luque CA, Rey JA (April 2002). "The discovery and status of sibutramine as an anti-obesity drug". European Journal of Pharmacology. 440 (2–3): 119–128. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01423-1. PMID 12007530.

- ^ Rockoff JD, Dooren JC (October 8, 2010). "Abbott Pulls Diet Drug Meridia Off US Shelves". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ Keating GM (2006). "Tramadol sustained-release capsules". Drugs. 66 (2): 223–230. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666020-00006. PMID 16451094. S2CID 22620947.

- ^ a b Gutierrez MA, Stimmel GL, Aiso JY (August 2003). "Venlafaxine: a 2003 update". Clinical Therapeutics. 25 (8): 2138–2154. doi:10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80210-2. PMID 14512125.

- ^ a b Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Reed SD, Ensrud KE, Manson JE, et al. (July 2014). "Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (7): 1058–1066. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1891. PMC 4179877. PMID 24861828.

- ^ Redrobe JP, Bourin M, Colombel MC, Baker GB (July 1998). "Dose-dependent noradrenergic and serotonergic properties of venlafaxine in animal models indicative of antidepressant activity". Psychopharmacology. 138 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s002130050638. PMID 9694520. S2CID 35064471.

- ^ a b Lieberman JA (2003). "History of the Use of Antidepressants in Primary Care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 5 (S7): 6–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ Ruelas EG, Diaz-Martinez A, Ruiz RM, Study TV, Group C (1997). "An open assessment of the acceptability, efficacy, and tolerance of venlafaxine in usual care settings". Current Therapeutic Research. 58 (9): 609–630. doi:10.1016/S0011-393X(97)80088-4.

- ^ a b c Grandoso L, Pineda J, Ugedo L (May 2004). "Comparative study of the effects of desipramine and reboxetine on locus coeruleus neurons in rat brain slices". Neuropharmacology. 46 (6): 815–823. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.11.033. PMID 15033341. S2CID 13228862.

- ^ Pacher P, Kecskemeti V (2004). "Cardiovascular side effects of new antidepressants and antipsychotics: new drugs, old concerns?". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 10 (20): 2463–2475. doi:10.2174/1381612043383872. PMC 2493295. PMID 15320756.

- ^ a b Brunello N, Mendlewicz J, Kasper S, Leonard B, Montgomery S, Nelson J, et al. (October 2002). "The role of noradrenaline and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibition in depression". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 12 (5): 461–475. doi:10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00057-3. hdl:11380/307479. PMID 12208564. S2CID 7989883.

- ^ a b c Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito SW (2008). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (6th ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 547–67, 581–582.

- ^ a b c d e Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, eds. (2006). Goodman & Gilman's: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Silverthorn DU, ed. (2007). Human Physiology (4 ed.). San Francisco: Pearson. pp. 383–384.

- ^ Nutt DJ, Forshall S, Bell C, Rich A, Sandford J, Nash J, et al. (July 1999). "Mechanisms of action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of psychiatric disorders". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 9 (Suppl 3): S81 – S86. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00030-9. PMID 10523062. S2CID 23634771.

- ^ Santarsieri D, Schwartz TL (2015). "Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: a quick guide for clinicians". Drugs in Context. 4 212290. doi:10.7573/dic.212290. PMC 4630974. PMID 26576188.

- ^ Clevenger SS, Malhotra D, Dang J, Vanle B, IsHak WW (January 2018). "The role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in preventing relapse of major depressive disorder". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 8 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1177/2045125317737264. PMC 5761909. PMID 29344343.

- ^ a b Zeind C, Carvalho MG (2018). Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs, 11e. Wolters Kluwer. pp. 1813–1833. ISBN 978-1-4963-1829-9.

- ^ a b c d Boot J, Cases M, Clark BP, Findlay J, Gallagher PT, Hayhurst L, et al. (February 2005). "Discovery and structure-activity relationships of novel selective norepinephrine and dual serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 15 (3): 699–703. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.11.025. PMID 15664840.

- ^ a b c Mahaney PE, Vu AT, McComas CC, Zhang P, Nogle LM, Watts WL, et al. (December 2006). "Synthesis and activity of a new class of dual acting norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: 3-(1H-indol-1-yl)-3-arylpropan-1-amines". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (24): 8455–8466. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.08.039. PMID 16973367.

- ^ Mahaney PE, Gavrin LK, Trybulski EJ, Stack GP, Vu TA, Cohn ST, et al. (July 2008). "Structure-activity relationships of the cycloalkanol ethylamine scaffold: discovery of selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (13): 4038–4049. doi:10.1021/jm8002262. PMID 18557608.

- ^ a b c Chen C, Dyck B, Fleck BA, Foster AC, Grey J, Jovic F, et al. (February 2008). "Studies on the SAR and pharmacophore of milnacipran derivatives as monoamine transporter inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (4): 1346–1349. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.011. PMID 18207394.

- ^ a b c Tamiya J, Dyck B, Zhang M, Phan K, Fleck BA, Aparicio A, et al. (June 2008). "Identification of 1S,2R-milnacipran analogs as potent norepinephrine and serotonin transporter inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (11): 3328–3332. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.025. PMID 18445525.

- ^ Vu AT, Cohn ST, Terefenko EA, Moore WJ, Zhang P, Mahaney PE, et al. (May 2009). "3-(Arylamino)-3-phenylpropan-2-olamines as a new series of dual norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 19 (9): 2464–2467. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.054. PMID 19329313.

- ^ Boot JR, Brace G, Delatour CL, Dezutter N, Fairhurst J, Findlay J, et al. (November 2004). "Benzothienyloxy phenylpropanamines, novel dual inhibitors of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 14 (21): 5395–5399. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.08.005. PMID 15454233.

- ^ Fish PV, Deur C, Gan X, Greene K, Hoople D, Mackenny M, et al. (April 2008). "Design and synthesis of morpholine derivatives. SAR for dual serotonin & noradrenaline reuptake inhibition". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (8): 2562–2566. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.050. PMID 18387300.

- ^ a b Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, Nelson JC, Shelton RC (December 2007). "Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (11): 1217–1227. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. PMID 17588546. S2CID 45621773.

- ^ Nemeroff CB, Thase ME (2007). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine treatment in depressed outpatients". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 41 (3–4): 351–359. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.009. PMID 16165158.

- ^ Marks DM, Shah MJ, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Park GY, Pae CU (December 2009). "Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for pain control: premise and promise". Current Neuropharmacology. 7 (4): 331–336. doi:10.2174/157015909790031201. PMC 2811866. PMID 20514212.

- ^ Beesdo K, Hartford J, Russell J, Spann M, Ball S, Wittchen HU (December 2009). "The short- and long-term effect of duloxetine on painful physical symptoms in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: results from three clinical trials". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 23 (8): 1064–1071. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.008. PMID 19643572.

- ^ Sansone RA, Sansone LA (June 2011). "SNRIs pharmacological alternatives for the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder?". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (6): 10–14. PMC 3140892. PMID 21779536.

- ^ Troy SM, Parker VP, Hicks DR, Pollack GM, Chiang ST (October 1997). "Pharmacokinetics and effect of food on the bioavailability of orally administered venlafaxine". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 37 (10): 954–961. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04270.x. PMID 9505987. S2CID 33518952.

- ^ Wichniak A, Wierzbicka A, Walęcka M, Jernajczyk W (August 2017). "Effects of Antidepressants on Sleep". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (9) 63. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0816-4. PMC 5548844. PMID 28791566.

- ^ "Helpful for chronic pain in addition to depression". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA (August 2023). "The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence". Molecular Psychiatry. 28 (8): 3243–3256. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0. PMC 10618090. PMID 35854107. S2CID 250646781.

- ^ Nutt DJ (2008). "Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69: 4–7. PMID 18494537.

- ^ Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS (June 2005). "Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 96 (6): 399–409. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_96696601.x. PMID 15910402.

- ^ Shelton RC, Miller AH (2011). "Inflammation in depression: is adiposity a cause?". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/rshelton. PMC 3181969. PMID 21485745.

- ^ a b Tynan RJ, Weidenhofer J, Hinwood M, Cairns MJ, Day TA, Walker FR (March 2012). "A comparative examination of the anti-inflammatory effects of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants on LPS stimulated microglia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 26 (3): 469–479. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2011.12.011. PMID 22251606. S2CID 39281923.

- ^ "Cambridge University Press - Service Announcement".

- ^ Lambert O, Bourin M (November 2002). "SNRIs: mechanism of action and clinical features". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2 (6): 849–858. doi:10.1586/14737175.2.6.849. PMID 19810918. S2CID 37792842.

- ^ a b c d "Pristiq Extended-Release- desvenlafaxine succinate tablet, extended release". DailyMed. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Effexor XR- venlafaxine hydrochloride capsule, extended release". DailyMed. 29 August 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Savella- milnacipran hydrochloride tablet, film coated Savella- milnacipran hydrochloride kit". DailyMed. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b Raouf M, Glogowski AJ, Bettinger JJ, Fudin J (August 2017). "Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the influence of binding affinity (Ki) on analgesia". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 42 (4): 513–517. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12534. PMID 28503727.

- ^ a b c Upadhyaya HP, Desaiah D, Schuh KJ, Bymaster FP, Kallman MJ, Clarke DO, et al. (March 2013). "A review of the abuse potential assessment of atomoxetine: a nonstimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Psychopharmacology. 226 (2). Springer Nature: 189–200. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-2986-z. PMC 3579642. PMID 23397050.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (Dec 2012). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Takano A, Halldin C, Farde L (2013-03-01). "SERT and NET occupancy by venlafaxine and milnacipran in nonhuman primates: a PET study". Psychopharmacology. 226 (1): 147–153. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2901-z. ISSN 1432-2072. PMID 23090625.

- ^ a b Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124.

- ^ Zhong Z, Wang L, Wen X, Liu Y, Fan Y, Liu Z (November 2017). "A meta-analysis of effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on blood pressure in depression treatment: outcomes from placebo and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor controlled trials". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 13: 2781–2796. doi:10.2147/NDT.S141832. PMC 5683798. PMID 29158677.

- ^ McIntyre RS et al. The hepatic safety profile of duloxetine: a review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(3):281–285.

- ^ Mladěnka P, Applová L, Patočka J, Costa VM, Remiao F, Pourová J, et al. (July 2018). "Comprehensive review of cardiovascular toxicity of drugs and related agents". Medicinal Research Reviews. 38 (4): 1332–1403. doi:10.1002/med.21476. PMC 6033155. PMID 29315692.

- ^ Chris Aiken: Antidepressants in Bipolar II Disorder, May 14, 2019. In: psychiatrictimes.com

- ^ "SNRI Antidepressants". poison.org. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- ^ Versiani M, Cassano G, Perugi G, Benedetti A, Mastalli L, Nardi A, et al. (January 2002). "Reboxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for panic disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (1): 31–37. doi:10.4088/jcp.v63n0107. PMID 11838623.

- ^ Olivier JD, Olivier B (2019-09-01). "Antidepressants and Sexual Dysfunctions: a Translational Perspective". Current Sexual Health Reports. 11 (3): 156–166. doi:10.1007/s11930-019-00205-y.

- ^ Clayton AH, Montejo AL (2006). "Major depressive disorder, antidepressants, and sexual dysfunction". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (Suppl 6): 33–37. PMID 16848675.

- ^ a b Jing E, Straw-Wilson K (July 2016). "Sexual dysfunction in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and potential solutions: A narrative literature review". The Mental Health Clinician. 6 (4): 191–196. doi:10.9740/mhc.2016.07.191. PMC 6007725. PMID 29955469.

- ^ "Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it". www.mdedge.com. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ a b Frank C (July 2008). "Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome". Canadian Family Physician. 54 (7): 988–992. PMC 2464814. PMID 18625822.

- ^ "SNRI Antidepressants". poison.org. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Tint A, Haddad PM, Anderson IM (May 2008). "The effect of rate of antidepressant tapering on the incidence of discontinuation symptoms: a randomised study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 22 (3): 330–332. doi:10.1177/0269881107081550. PMID 18515448. S2CID 145217439.

- ^ a b Cochran KA, Cavallari LH, Shapiro NL, Bishop JR (August 2011). "Bleeding incidence with concomitant use of antidepressants and warfarin". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 33 (4): 433–438. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e318224996e. PMC 3212440. PMID 21743381.

- ^ Cheng YL, Hu HY, Lin XH, Luo JC, Peng YL, Hou MC, et al. (November 2015). "Use of SSRI, But Not SNRI, Increased Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan". Medicine. 94 (46) e2022. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002022. PMC 4652818. PMID 26579809.

- ^ Curr Neurol, Neurosci Rep. (2022). "Visual Snow: Updates on Pathology". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 22 (3). National Institutes of Health: 209–217. doi:10.1007/s11910-022-01182-x. PMC 8889058. PMID 35235167.

- ^ "Duloxetine: Drug Information". UpToDate. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Perahia DG, Pritchett YL, Kajdasz DK, Bauer M, Jain R, Russell JM, et al. (January 2008). "A randomized, double-blind comparison of duloxetine and venlafaxine in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 42 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.008. PMID 17445831.

- ^ Wilson E, Lader M (December 2015). "A review of the management of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 5 (6): 357–368. doi:10.1177/2045125315612334. PMC 4722507. PMID 26834969.

- ^ a b Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M, Offidani E, Cosci F, Guidi J (2018). "Withdrawal Symptoms after Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation: Systematic Review" (PDF). Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 87 (4): 195–203. doi:10.1159/000491524. PMID 30016772.

- ^ Taylor D, Lenox-Smith A, Bradley A (June 2013). "A review of the suitability of duloxetine and venlafaxine for use in patients with depression in primary care with a focus on cardiovascular safety, suicide and mortality due to antidepressant overdose". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 3 (3): 151–161. doi:10.1177/2045125312472890. PMC 3805457. PMID 24167687.

- ^ Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Keenaghan M (2019). "Serotonin Syndrome". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29493999. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ "2009 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions" (PDF). SDI/Verispan, VONA, full year 2009. www.drugtopics.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Llorca PM, Fernandez JL (April 2007). "Escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: clinical efficacy, tolerability and cost-effectiveness vs. venlafaxine extended-release formulation". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 61 (4): 702–710. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01335.x. PMID 17394446.

- ^ a b Dubovicky M, Belovicova K, Csatlosova K, Bogi E (September 2017). "Risks of using SSRI / SNRI antidepressants during pregnancy and lactation". Interdisciplinary Toxicology. 10 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1515/intox-2017-0004. PMC 6096863. PMID 30123033.

- ^ Benevent J, Araujo M, Karki S, Delarue-Hurault C, Waser J, Lacroix I, et al. (July 2023). "Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Women Treated With Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: A Comparative Study Using the EFEMERIS Database". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 84 (4): 47872. doi:10.4088/JCP.22m14734. PMID 37437238.

- ^ Tran YH, Huynh HK, Faas MM, de Vos S, Groen H (February 2022). "Antidepressant use during pregnancy and development of preeclampsia: A focus on classes of action and specific transporters/receptors targeted by antidepressants". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 146: 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.12.038. PMID 34959164.

- ^ Smith S, Martin F, Rai D, Forbes H (January 2024). "Association between antidepressant use during pregnancy and miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 14 (1) e074600. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074600. PMC 10824002. PMID 38272551.

- ^ Wiggs KK, Sujan AC, Rickert ME, Quinn PD, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, et al. (June 2022). "Maternal Serotonergic Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy and Risk of Seizures in Children". Neurology. 98 (23): e2329 – e2336. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200516. PMC 9202527. PMID 35545445.

- ^ a b Strawn JR, Mills JA, Sauley BA, Welge JA (April 2018). "The Impact of Antidepressant Dose and Class on Treatment Response in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 57 (4): 235–244.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.015. PMC 5877120. PMID 29588049.

- ^ a b c d Strawn JR, Vaughn S, Ramsey LB (April 2022). "Pediatric Psychopharmacology for Depressive and Anxiety Disorders". Focus. 20 (2): 184–190. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20210036. PMC 10153505. PMID 37153132.

- ^ Strawn JR, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Stroud CE, Cai N, et al. (April 2015). "A randomized, placebo-controlled study of duloxetine for the treatment of children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 54 (4): 283–293. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.008. PMID 25791145.

- ^ Castagna PJ, Farahdel E, Potenza MN, Crowley MJ (May 2023). "The current state-of-the-art in pharmacotherapy for pediatric generalized anxiety disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 24 (7): 835–847. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2199921. PMC 10197951. PMID 37074259.

- ^ Brender R, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM (October 2021). "An update on antidepressant pharmacotherapy in late-life depression". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 22 (14): 1909–1917. doi:10.1080/14656566.2021.1921736. PMID 33910422.

- ^ Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, Ismail Z, Rabheru K, Rapoport MJ (August 2014). "A systematic approach to pharmacotherapy for geriatric major depression". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 30 (3): 517–534. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2014.05.002. PMC 4122285. PMID 25037293.

- ^ Simon G (October 2019). "Review: In older adults with acute major depression, SNRIs, but not SSRIs, increase adverse events vs placebo". Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (8): JC39. doi:10.7326/acpj201910150-039. PMID 31610552.

- ^ "More adverse events with SNRIs than placebo in older patients". The Brown University Psychopharmacology Update. 30 (10): 7–8. October 2019. doi:10.1002/pu.30488. ISSN 1068-5308.

- ^ Ferreira GE, Abdel-Shaheed C, Underwood M, Finnerup NB, Day RO, McLachlan A, et al. (February 2023). "Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants for pain in adults: overview of systematic reviews". BMJ. 380 e072415. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-072415. PMC 9887507. PMID 36725015.

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Definition

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of pharmacological agents that inhibit the reuptake of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) by blocking their respective presynaptic transporters, the serotonin transporter (SERT) and the norepinephrine transporter (NET).[1][2] This dual inhibition prevents the reabsorption of these monoamine neurotransmitters into the presynaptic neuron, thereby increasing their extracellular concentrations in the synaptic cleft.[10][12] By elevating synaptic levels of both 5-HT and NE, SNRIs enhance neurotransmission involving these catecholamines, which differentiates them from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that primarily target SERT or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) that focus on NET.[1][3] This balanced or selective modulation of monoamine systems is thought to contribute to their therapeutic effects in conditions involving dysregulated serotonin and norepinephrine signaling.[13] SNRIs are primarily classified as antidepressants due to their efficacy in treating major depressive disorder, and they also serve as analgesics for chronic pain management by influencing descending pain inhibitory pathways.[6][8] Within the SNRI class, drugs vary in their potency ratios for SERT versus NET inhibition; for instance, venlafaxine exhibits a serotonin-preferring profile with approximately 30-fold higher affinity for SERT than NET, while others like duloxetine show a more balanced 10-fold selectivity for serotonin reuptake inhibition.[14][15]Classification Within Antidepressants

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are positioned as second-generation antidepressants, emerging after the first-generation tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and alongside selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). This classification reflects their development in the late 1980s and 1990s as an evolution from earlier agents, offering improved tolerability while targeting multiple monoamine systems.[16] Unlike the single-target focus of SSRIs on serotonin reuptake, SNRIs' dual inhibition of both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake enables a broader neurochemical impact, which is associated with enhanced efficacy in treating major depressive disorder, particularly in cases refractory to SSRIs.[17] SNRIs are further subclassified based on their relative selectivity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) versus the norepinephrine transporter (NET), determined by binding affinity measures such as inhibition constants (Ki values). This subclassification highlights variations in their pharmacological profiles, influencing clinical applications. Serotonin-preferring SNRIs, exemplified by venlafaxine, demonstrate markedly higher affinity for SERT (Ki = 82 nM) than NET (Ki = 2480 nM), yielding a selectivity ratio (NET/SERT) of approximately 30, which results in predominant serotonergic effects at lower doses.[18] In contrast, balanced SNRIs like duloxetine exhibit more equipotent inhibition, with Ki values of 0.8 nM for SERT and 7.5 nM for NET, corresponding to a selectivity ratio of about 9 and allowing concurrent modulation of both neurotransmitters across therapeutic doses.[18] Norepinephrine-preferring SNRIs, such as levomilnacipran, show reduced SERT selectivity (Ki = 11.2 nM for SERT and 92.2 nM for NET, ratio ≈8), providing relatively greater norepinephrine reuptake inhibition compared to serotonin-preferring agents and resembling hybrids with selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors like reboxetine.[19]History

Early Development

The development of serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) traces its origins to the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), which emerged in the mid-20th century as the first effective pharmacological treatments for depression. Imipramine, synthesized in 1951 and introduced clinically in the late 1950s, represented a breakthrough as the inaugural TCA, discovered serendipitously during research into antipsychotic agents.[20] This compound non-selectively inhibited the reuptake of both serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) at their respective transporters, thereby elevating synaptic levels of these monoamines and alleviating depressive symptoms in patients.[20] Throughout the 1960s, further TCAs such as amitriptyline and desipramine expanded on imipramine's foundation, confirming the therapeutic relevance of dual monoamine reuptake inhibition while highlighting the need for refined selectivity.[21] These early agents laid the groundwork for subsequent antidepressants by establishing the monoamine hypothesis of depression, which posits that deficiencies in 5-HT and NE contribute to mood disorders.[20] A pivotal advancement in the 1970s involved the synthesis of viloxazine, developed by Imperial Chemical Industries as a prototype selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI) for depression treatment.[22] Unlike the broad-spectrum TCAs, viloxazine primarily targeted NE reuptake with minimal impact on other systems, facilitating the transition toward dual-action compounds that balanced 5-HT and NE modulation without excessive non-specificity.[23] Early synthesis efforts for these precursors faced significant challenges, particularly the tricyclic structures' propensity for off-target effects, including potent antihistamine activity at H1 receptors, which contributed to sedation and other adverse reactions.[24] Such interactions complicated clinical utility and spurred research into structurally modified agents to enhance selectivity and reduce unwanted receptor bindings.[24]Key Approvals and Milestones

The development of serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) marked a significant advancement in antidepressant therapy, with the first regulatory approval occurring in 1993. Venlafaxine, first synthesized in the late 1980s by Wyeth, and marketed as Effexor, received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval on December 28, 1993, for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), establishing it as the inaugural SNRI and offering an alternative to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants with a dual mechanism targeting both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake.[25][26] Subsequent approvals expanded the class's therapeutic scope beyond depression. Duloxetine, branded as Cymbalta, was approved by the FDA on August 3, 2004, initially for MDD and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, later gaining indications for generalized anxiety disorder in 2007, fibromyalgia in 2008, and chronic musculoskeletal pain in 2010, highlighting the SNRI class's efficacy in managing both mood and pain disorders.[27][28] Milnacipran, under the trade name Savella, followed with FDA approval on January 14, 2009, specifically for the management of fibromyalgia, broadening SNRI applications to non-psychiatric chronic pain conditions despite its earlier approval in Europe for depression.[29] Further milestones included the approval of levomilnacipran extended-release capsules (Fetzima) by the FDA on July 25, 2013, for adults with MDD, introducing a more norepinephrine-selective SNRI profile that showed potential advantages in certain depressive symptoms.[30] Desvenlafaxine, the active metabolite of venlafaxine and marketed as Pristiq, had been approved earlier on February 29, 2008, for MDD; clinical studies have supported its off-label use in anxiety disorders, though formal FDA expansion remains pending as of 2025.[31][32]Mechanism of Action

Serotonin Reuptake Inhibition

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) primarily block serotonin reuptake by binding to the serotonin transporter (SERT), a sodium-dependent transmembrane protein expressed on presynaptic serotonergic neurons in the central nervous system. This binding occurs at the central substrate-binding site (S1 pocket) of SERT, where SNRIs competitively inhibit the transporter's ability to translocate serotonin (5-HT) from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic terminal. As a result, synaptic clearance of 5-HT is reduced, leading to prolonged availability of the neurotransmitter in the extracellular space.[12] The accumulation of extracellular 5-HT enhances serotonergic signaling by stimulating postsynaptic receptors, notably the 5-HT1A autoreceptors and heteroreceptors, as well as 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C subtypes, which modulate neuronal excitability and downstream intracellular pathways such as adenylate cyclase and phospholipase C activation. This receptor activation contributes to the neuroplastic changes associated with antidepressant effects, though the acute increase in 5-HT can initially desensitize presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors over time.[33][34] Affinity for SERT varies among SNRIs, influencing their potency in serotonin reuptake inhibition; for instance, venlafaxine demonstrates a high affinity with a Ki value of 82 nM for human SERT in vitro, enabling effective blockade at clinically relevant doses, while its metabolite desvenlafaxine maintains similar potency. Other SNRIs, such as duloxetine, exhibit even stronger SERT inhibition with a Ki of 0.8 nM, highlighting structural differences that optimize binding interactions within the SERT pocket. These variations underscore the dose-dependent nature of serotonin reuptake blockade in SNRIs, where lower doses predominantly target SERT before norepinephrine effects become prominent.[18][35]Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibition

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) exert their effects on the noradrenergic system primarily through blockade of the norepinephrine transporter (NET), a sodium/chloride-dependent membrane protein that facilitates the reuptake of norepinephrine (NE) from the synaptic cleft back into presynaptic neurons.[1] By binding to NET and inhibiting this reuptake process, SNRIs increase extracellular NE concentrations in key brain regions such as the locus coeruleus and prefrontal cortex, enhancing noradrenergic neurotransmission.[2] This elevation of synaptic NE levels is central to the therapeutic actions of SNRIs in conditions involving noradrenergic dysregulation. The increased synaptic NE resulting from NET inhibition activates various adrenergic receptors, including presynaptic α₂-adrenergic autoreceptors on noradrenergic neurons, which provide negative feedback to modulate NE release.[36] Initially, this activation limits excessive NE efflux, but chronic treatment leads to desensitization of these autoreceptors, ultimately promoting sustained noradrenergic signaling.[37] Postsynaptically, elevated NE stimulates β₁-adrenergic receptors, which are coupled to Gₛ proteins and increase cyclic AMP levels, contributing to enhanced arousal, attention, and vigilance.[38] In the context of pain modulation, noradrenergic enhancement via these pathways inhibits nociceptive transmission in the spinal cord, particularly through α₂-adrenergic mechanisms, providing analgesic effects.[8] Affinity for NET varies among SNRIs, influencing their noradrenergic potency; for instance, duloxetine demonstrates balanced inhibition with an IC₅₀ of approximately 7 nM for human NET, allowing effective NE reuptake blockade at clinically relevant doses. In contrast, serotonin-preferring SNRIs like venlafaxine exhibit weaker NET affinity, with an IC₅₀ around 2,550 nM, resulting in more selective serotonergic effects at lower doses.[39] This differential binding underscores the spectrum of noradrenergic engagement across the class. The combined elevation of NE and serotonin synergistically amplifies antidepressant efficacy beyond isolated monoamine effects.Synergistic Effects

The dual reuptake inhibition characteristic of SNRIs facilitates reciprocal neuroadaptations between serotonergic and noradrenergic systems, particularly through downregulation of key autoreceptors and heteroreceptors. Chronic elevation of synaptic serotonin desensitizes presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors on raphe nuclei neurons, thereby reducing inhibitory feedback and enhancing serotonin release.[33] Concurrently, increased synaptic norepinephrine desensitizes α2-adrenergic autoreceptors on locus coeruleus neurons, promoting norepinephrine release, while also desensitizing α2-heteroreceptors located on serotonergic terminals, which further disinhibits serotonin outflow.[40] This bidirectional interaction results in amplified neurotransmission of both monoamines, exceeding the effects achievable through isolated inhibition of either system.[41] In addition to enhancing acute monoamine signaling, SNRIs contribute to long-term therapeutic benefits by promoting neuroplasticity, largely via upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Elevated levels of serotonin and norepinephrine activate signaling pathways, such as TrkB receptor phosphorylation, that increase BDNF expression in regions like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, fostering dendritic arborization, synaptogenesis, and neuronal survival.[42] This BDNF-mediated plasticity improves overall monoamine efficacy by strengthening circuit connectivity in mood-regulating networks, a process integral to the sustained antidepressant action of SNRIs.[43] Preclinical evidence from animal models underscores the superior efficacy of dual reuptake blockade over single-modality inhibition. In rodent chronic unpredictable stress paradigms, SNRIs like duloxetine elicit greater reductions in depressive-like behaviors—such as immobility in the forced swim test—compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors alone, attributable to the synergistic enhancement of monoamine tone and neuroplastic adaptations.[44] Similarly, dual inhibitors demonstrate more robust reversal of anhedonia and anxiety-like symptoms in olfactory bulbectomy models, highlighting the additive value of combined serotonergic and noradrenergic modulation.[45]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics