Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protriptyline

View on Wikipedia | |

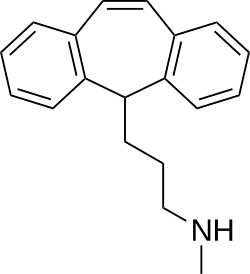

Above: molecular structure of protriptyline

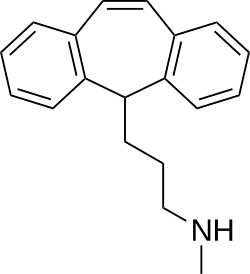

Below: 3D representation of a protriptyline molecule | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vivactyl, others |

| Other names | Amimethyline; Protriptyline hydrochloride; MK-240 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604025 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 77–93%[2] |

| Protein binding | 92%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 54–92 hours |

| Excretion | Urine: 50%[2] Feces: minor[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.474 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H21N |

| Molar mass | 263.384 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Protriptyline, sold under the brand name Vivactil among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), specifically a secondary amine. Uniquely among most of the TCAs, protriptyline tends to be energizing instead of sedating, and is sometimes used for narcolepsy to achieve a wakefulness-promoting effect.[3]

TCAs including protriptyline are also used to reduce the incidence of recurring headaches such as migraine, and for other types of chronic pain.[4]

Medical uses

[edit]Protriptyline is used primarily to treat depression and to treat the combination of symptoms of anxiety and depression.[5] Like most antidepressants of this chemical and pharmacological class, protriptyline has also been used in limited numbers of patients to treat panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, enuresis, eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa, cocaine dependency, and the depressive phase of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive) disorder. It has also been used to support smoking cessation programs.[6]

Protriptyline is available as 5 mg and 10 mg tablets.[7] Doses range from 15 to 40 mg per day and can be taken in one daily dose or divided into up to four doses daily.[7] Some people with severe depression may require up to 60 mg per day.[7]

In adolescents and people over age 60, therapy should be initiated at a dose of 5 mg three times a day and increased under the supervision of a physician as needed.[7] Patients over age 60 who are taking daily doses of 20 mg or more should be closely monitored for side effects such as rapid heart rate and urinary retention.[7]

Like all TCAs, protriptyline should be used cautiously and with close physician supervision. This is especially so for persons with glaucoma, especially angle-closure glaucoma (the most severe form) or urinary retention, for men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate gland), and for the elderly. Before starting treatment, people should discuss the relative risks and benefits of treatment with their doctors to help determine if protriptyline is the right antidepressant for them.[8]

Contraindications

[edit]Protriptyline may increase heart rate and stress on the heart.[9] It may be dangerous for people with cardiovascular disease, especially those who have recently had a heart attack, to take this drug or other antidepressants in the same pharmacological class.[9] In rare cases in which patients with cardiovascular disease must take protriptyline, they should be monitored closely for cardiac rhythm disturbances and signs of cardiac stress or damage.[9]

When protriptyline is used to treat the depressive component of schizophrenia, psychotic symptoms may be aggravated. Likewise, in manic-depressive psychosis, depressed patients may experience a shift toward the manic phase if they are treated with an antidepressant drug. Paranoid delusions, with or without associated hostility, may be exaggerated.[7] In any of these circumstances, it may be advisable to reduce the dose of protriptyline or to use an antipsychotic drug concurrently.[7]

Side effects

[edit]Protriptyline shares side effects common to all TCAs.[5] The most frequent of these are dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, increased heart rate, sedation, irritability, decreased coordination, anxiety, blood disorders, confusion, decreased libido, dizziness, flushing, headache, impotence, insomnia, low blood pressure, nightmares, rapid or irregular heartbeat, rash, seizures, sensitivity to sunlight, stomach and intestinal problems.[7] Other more complicated side effects include; chest pain or heavy feeling, pain spreading to the arm or shoulder, nausea, sweating, general ill feeling; sudden numbness or weakness, especially on one side of the body; sudden headache, confusion, problems with vision, speech, or balance; hallucinations, or seizure (convulsions); easy bruising or bleeding, unusual weakness; restless muscle movements in your eyes, tongue, jaw, or neck; urinating less than usual or not at all; extreme thirst with headache, nausea, vomiting, and weakness; or feeling light-headed or fainting.[7]

Dry mouth, if severe to the point of causing difficulty speaking or swallowing, may be managed by dosage reduction or temporary discontinuation of the drug.[5] Patients may also chew sugarless gum or suck on sugarless candy in order to increase the flow of saliva. Some artificial saliva products may give temporary relief.[5] Men with prostate enlargement who take protriptyline may be especially likely to have problems with urinary retention.[7] Symptoms include having difficulty starting a urine flow and more difficulty than usual passing urine.[7] In most cases, urinary retention is managed with dose reduction or by switching to another type of antidepressant.[7] In extreme cases, patients may require treatment with bethanechol, a drug that reverses this particular side effect.[7]

A common problem with TCAs is sedation (drowsiness, lack of physical and mental alertness), but protriptyline is considered the least sedating agent among this class of agents.[8] Its side effects are especially noticeable early in therapy.[8] In most people, early TCA side effects decrease or disappear entirely with time, but, until then, patients taking protriptyline should take care to assess which side effects occur in them and should not perform hazardous activities requiring mental acuity or coordination.[10] Protriptyline may increase the possibility of having seizures.[10]

Withdrawal

[edit]Though not indicative of addiction, abrupt cessation of treatment after prolonged therapy may produce nausea, headache, and malaise.[9]

List of side effects

[edit]- Cardiovascular: Myocardial infarction; stroke; heart block; arrhythmias; hypotension, particularly orthostatic hypotension; hypertension; tachycardia; palpitation.[11]

- Psychiatric: Confusional states (especially in the elderly) with hallucinations, disorientation, delusions, anxiety, restlessness, agitation; hypomania; exacerbation of psychosis; insomnia, panic, and nightmares.[5]

- Neurological: Seizures; incoordination; ataxia; tremors; peripheral neuropathy; numbness, tingling, and paresthesias of extremities; extrapyramidal symptoms; drowsiness; dizziness; weakness and fatigue; headache; syndrome of inappropriate ADH (antidiuretic hormone) secretion; tinnitus; alteration in EEG patterns.[5]

- Anticholinergic: Paralytic ileus; hyperpyrexia; urinary retention, delayed micturition, dilatation of the urinary tract; constipation; blurred vision, disturbance of accommodation, increased intraocular pressure, mydriasis; dry mouth and rarely associated sublingual adentitis.[5]

- Allergic: Drug fever; petechiae, skin rash, urticaria, itching, photosensitization (avoid excessive exposure to sunlight); edema (general, or of face and tongue).[5]

- Hematologic: Agranulocytosis; bone marrow depression; leukopenia;thrombocytopenia; purpura; eosinophilia.[5]

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea and vomiting; anorexia; epigastric distress; diarrhea; peculiar taste; stomatitis; abdominal cramps; black tongue.[5]

- Endocrine: Impotence, increased or decreased libido: gynecomastia in the male; breast enlargement and galactorrhea in the female; testicular swelling; elevation or depression of blood sugar levels.[5]

- Other: Jaundice (simulating obstructive); altered liver function; parotid swelling; alopecia; flushing; weight gain or loss; urinary frequency, nocturia; perspiration.[5]

Overdose

[edit]Deaths may occur from overdose with this class of drugs.[10] Multiple drug ingestion (including alcohol) is common in deliberate TCA overdose.[10] As management of overdose is complex and changing, it is recommended that the physician contact a poison control center for current information on treatment.[5] Signs and symptoms of toxicity develop rapidly after TCA overdose, therefore, hospital monitoring is required as soon as possible.[10]

Critical manifestations of overdose include: cardiac dysrhythmias, severe hypotension, convulsions, and CNS depression, including coma.[7] Changes in the electrocardiogram, particularly in QRS axis or width, are clinically significant indicators of TCA toxicity.[7] Other signs of overdose may include: confusion, disturbed concentration, transient visual hallucinations, dilated pupils, agitation, hyperactive reflexes, stupor, drowsiness, muscle rigidity, vomiting, hypothermia, hyperpyrexia.[7]

Interactions

[edit]The side effects of protriptyline are increased when it is taken with central nervous system depressants, such as alcoholic beverages, sleeping medications, other sedatives, or antihistamines, as well as with other antidepressants including SSRIs, SNRIs or monoamine oxidase inhibitors.[10] It may be dangerous to take protriptyline in combination with these substances.[10]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 19.6 | Human | [13] |

| NET | 1.41 | Human | [13] |

| DAT | 2,100 | Human | [13] |

| 5-HT1A | 3,800 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT2A | 70 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | 130 | Human | [15] |

| α2 | 6,600 | Human | [15] |

| β | >10,000 | Monkey/rat | [16] |

| D2 | 2,300 | Human | [15] |

| H1 | 7.2–25 | Human | [17][15] |

| H2 | 398 | Human | [17] |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [17] |

| H4 | 15,100 | Human | [17] |

| mACh | 25 | Human | [15][18] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Protriptyline acts by decreasing the reuptake of norepinephrine and to a lesser extent serotonin (5-HT) in the brain.[9] Its affinity for the human norepinephrine transporter (NET) is 1.41 nM, 19.6 nM for the serotonin transporter and 2,100 nM for the dopamine transporter.[19] TCAs act to change the balance of naturally occurring chemicals in the brain that regulate the transmission of nerve impulses between cells. Protriptyline increases the concentration of norepinephrine and serotonin (both chemicals that stimulate nerve cells) and, to a lesser extent, blocks the action of another brain chemical, acetylcholine.[9] The therapeutic effects of protriptyline, like other antidepressants, appear slowly. Maximum benefit is often not evident for at least two weeks after starting the drug.[9]

Protriptyline is a TCA.[7] It was thought that TCAs work by inhibiting the reuptake of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin by neurons.[7] However, this response occurs immediately, yet mood does not lift for around two weeks.[7] It is now thought that changes occur in receptor sensitivity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.[7] The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, a part of the brain involved in emotions. TCAs are also known as effective analgesics for different types of pain, especially neuropathic or neuralgic pain.[7] A precise mechanism for their analgesic action is unknown, but it is thought that they modulate anti-pain opioid systems in the central nervous system via an indirect serotonergic route. TCAs are also effective in migraine prophylaxis, but not in abortion of acute migraine attack.[7] The mechanism of their anti-migraine action is also thought to be serotonergic, similar to psilocybin.[7]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Metabolic studies indicate that protriptyline is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and is rapidly sequestered in tissues.[5] Relatively low plasma levels are found after administration, and only a small amount of unchanged drug is excreted in the urine of dogs and rabbits.[5] Preliminary studies indicate that demethylation of the secondary amine moiety occurs to a significant extent, and that metabolic transformation takes place in the liver.[5] It penetrates the brain rapidly in mice and rats, and moreover that which is present in the brain is almost all unchanged drug.[5] Studies on the disposition of radioactive protriptyline in human test subjects showed significant plasma levels within 2 hours, peaking at 8 to 12 hours, then declining gradually.[5]

Urinary excretion studies in the same subjects showed significant amounts of radioactivity in 2 hours.[5] The rate of excretion was slow.[5] Cumulative urinary excretion during 16 days accounted for approximately 50% of the drug. The fecal route of excretion did not seem to be important.[5]

Protriptyline has uniquely low dosing among TCAs, likely due to its exceptionally long terminal half-life.[20] It is used in dosages of 15 to 40 mg/day, whereas most other TCAs are used at dosages of 75 to 300 mg/day.[20] The maximum dose is 60 mg/day.[20] Therapeutic levels of protriptyline are typically in the range of 70 to 250 ng/mL (266-950 nmol/L), which is similar to that of other TCAs[21][22][23]

Chemistry

[edit]Protriptyline is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzocycloheptadiene, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[24] Other dibenzocycloheptadiene TCAs include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and butriptyline.[24][25] Protriptyline is a secondary amine TCA, with its N-methylated analog N–methylprotriptyline being a tertiary amine, and a structural isomer of amitriptyline.[26][27] The tertiary amine analog of protriptyline, N–methylprotriptyline, has not been marketed. Other secondary amine TCAs include desipramine and nortriptyline.[28][29] The chemical name of protriptyline is 3-(5H-dibenzo[a,d][7]annulen-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C19H21N1 with a molecular weight of 263.377 g/mol.[30] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the free base form is not used.[30][31] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 438-60-8 and of the hydrochloride is 1225-55-4.[30][31]

History

[edit]Protriptyline was developed by Merck.[32] It was patented in 1962 and first appeared in the literature in 1964.[32] The drug was first introduced for the treatment of depression in 1966.[32][33]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Protriptyline is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while protriptyline hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, and BANM.[30][31][34][35] Its generic name in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are protriptylina, in German is protriptylin, and in Latin is protriptylinum.[31][35]

Brand names

[edit]Protriptyline is or has been marketed throughout the world under a variety of brand names including Anelun, Concordin, Maximed, Triptil, and Vivactil.[30][31]

Availability

[edit]The sale of protriptyline was discontinued in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Ireland in 2000.[36] It remains available worldwide only in the United States as of 2024.[37][38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ a b c d Lemke TL, Williams DA (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 588–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^ Schmidt, H. S., Clark, R. W., & Hyman, P. R. (1977). Protriptyline: An effective agent in the treatment of the narcolepsy-cataplexy syndrome and hypersomnia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(2), 183–185. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.134.2.183

- ^ Cohen, G. L. (1997). "Protriptyline, chronic tension-type headaches, and weight loss in women". Headache. 37 (7): 433–436. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3707433.x. ISSN 0017-8748. PMID 9277026.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u DURAMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., . (Ed.). (2007). Protriptyline drug facts. Pomona, New York : Barr Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- ^ ULTRAM, . (Ed.). (2007). Protriptyline. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. AHFS Drug Information 2002. Bethesda: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 2002.

- ^ a b c Kirchheiner J, Nickchen K, Bauer M, Wong ML, Licinio J, Roots I, Brockmöller J (May 2004). "Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants and antipsychotics: the contribution of allelic variations to the phenotype of drug response". Molecular Psychiatry. 9 (5): 442–473. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001494. PMID 15037866.

- ^ a b c d e f g Advameg, Inc. (2010). Protriptyline at MindDisorders.com

- ^ a b c d e f g DeVane, C. Lindsay, Pharm.D. "Drug Therapy for Mood Disorders." In Fundamentals of Monitoring Psychoactive Drug Therapy. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1990.

- ^ Sériès F, Cormier Y (October 1990). "Effects of protriptyline on diurnal and nocturnal oxygenation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 113 (7): 507–11. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-7-507. PMID 2393207.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 132 (2–3): 115–21. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ^ a b c d e Richelson E, Nelson A (1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 230 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)21446-X. PMID 6086881.

- ^ Bylund DB, Snyder SH (1976). "Beta adrenergic receptor binding in membrane preparations from mammalian brain". Mol. Pharmacol. 12 (4): 568–80. doi:10.1016/S0026-895X(25)10785-2. PMID 8699.

- ^ a b c d Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H1R, H2R, H3R, and H4R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- ^ El-Fakahany E, Richelson E (1983). "Antagonism by antidepressants of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors of human brain". Br. J. Pharmacol. 78 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb17361.x. PMC 2044798. PMID 6297650.

- ^ "PDSP Database - UNC". PDSP Ki Database. University of North Carolina. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Stahl SM (31 March 2017). Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 619–. ISBN 978-1-108-22874-9.

- ^ Van Leeuwen AM, Bladh ML (19 February 2016). Textbook of Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing: Practical Application of Nursing Process at the Bedside. F.A. Davis. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8036-5845-5.

- ^ Pagliaro LA, Pagliaro AM (1999). Psychologists' Psychotropic Drug Reference. Psychology Press. pp. 545–. ISBN 978-0-87630-964-3.

- ^ Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9.

- ^ a b Ritsner MS (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6.

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 580–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ Cutler NR, Sramek JS, Narang PK (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3.

- ^ Anzenbacher P, Zanger UM (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6.

- ^ Anthony PK (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9.

- ^ Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3.

- ^ a b c d e Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. p. 1040. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 894–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b c Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chem. Commun. (25): 3677–92. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ^ Dart RC (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ a b "Protriptyline Uses, Side Effects & Warnings".

- ^ "Protriptyline". www.choiceandmedication.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-22.

- ^ "Protriptyline". Drugs.com. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-08-17. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

Protriptyline

View on GrokipediaTherapeutic uses

Approved indications

Protriptyline is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of symptoms of mental depression in adults under close medical supervision. It is particularly suitable for patients exhibiting withdrawn or anergic states, which align with depressive presentations involving psychomotor retardation and lethargy.[3] As a tricyclic antidepressant, protriptyline exerts its therapeutic effects by inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin in the synaptic cleft, thereby elevating their concentrations and modulating mood-regulating neurotransmission to alleviate core depressive symptoms.[4] For approved use in major depressive disorder, the initial adult dosage is 15 to 40 mg per day, divided into three or four doses to minimize side effects and improve tolerability; this may be gradually titrated upward to a maximum of 60 mg per day based on clinical response and tolerance. Lower starting doses of 5 mg three times daily are recommended for elderly patients, with cautious increases and cardiovascular monitoring for doses exceeding 20 mg per day.[3][7] Clinical trials supporting its approval have demonstrated protriptyline's efficacy in improving mood, energy levels, and sleep disturbances in patients with major depressive disorder, with a notably faster onset of action—often within one week—compared to other tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine or amitriptyline. Double-blind comparative studies have further confirmed its antidepressant response rates as comparable to amitriptyline in treating severe depressions.[8][9]Off-label uses

Protriptyline has been investigated for off-label use in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents, though evidence is limited. A small naturalistic assessment in 13 pediatric patients (ages not specified as adults) treated with 5-30 mg/day showed modest reductions in ADHD symptoms and clinical severity after at least four weeks in 11 continuing patients, but only 45% were positive responders, with 46% experiencing significant adverse effects; the study concluded that findings do not support its routine clinical utility in complex ADHD cases.[10] The drug is also employed off-label for narcolepsy and excessive daytime sleepiness, leveraging its noradrenergic activity to produce stimulant-like effects that enhance wakefulness. A series of case reports from the 1970s demonstrated that bedtime doses of 10-20 mg effectively controlled arousal dysfunction, sleep attacks, and cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy-cataplexy syndrome.[11] Typical dosing for these indications ranges from 5-20 mg/day, often administered at night to minimize interference with sleep onset.[12] As an adjunctive therapy in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), protriptyline has shown potential to reduce REM sleep fragmentation and improve oxygen saturation, based on research from the 1970s and 1980s. A double-blind crossover trial in patients with OSA found that protriptyline significantly decreased the apnea index and improved respiratory disturbance measures, though it did not fully resolve the condition.[13] Another study reported reductions in apneic episodes with nightly doses of 5-20 mg over periods of two to 18 months in nine patients.[14] Protriptyline sees limited off-label application in anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety, especially in cases comorbid with depression. Its utility in this context stems from its tricyclic antidepressant properties, which can help alleviate anxiety symptoms alongside mood stabilization.[4] Protriptyline has also been studied off-label for the prevention of certain types of headaches, particularly chronic daily headaches. In one study of 25 women treated with 20 mg daily for 12 weeks, participants experienced an 86% reduction in monthly headache frequency.[4]Contraindications and precautions

Absolute contraindications

Protriptyline is contraindicated during the acute recovery phase following myocardial infarction, as its quinidine-like effects on cardiac conduction can precipitate life-threatening arrhythmias in this vulnerable period.[15][3] Similarly, administration during the acute recovery phase following myocardial infarction is prohibited, as it may exacerbate underlying cardiac instability and increase the risk of further complications.[3] The drug must not be used in individuals with known hypersensitivity to protriptyline or other tricyclic antidepressants, due to the risk of severe allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.[3][4] Concurrent administration with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) is strictly forbidden, as it can lead to serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis; a minimum washout period of 14 days is required after discontinuing an MAOI before initiating protriptyline.[3][4] Protriptyline is not recommended in children under 12 years of age due to insufficient safety and efficacy data and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.[16][15]Special precautions

Patients with cardiovascular disease require special precautions when using protriptyline, as it can cause tachycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias, and prolongation of conduction time. Close monitoring of the cardiovascular system, including electrocardiogram (ECG) assessments for QT prolongation and conduction delays, is essential in individuals with heart block or arrhythmias. This caution extends to those recovering from recent myocardial infarction, where protriptyline is absolutely contraindicated but requires careful evaluation in other cardiac conditions.[17] In patients with glaucoma, protriptyline's anticholinergic effects may lead to pupillary dilation and increased intraocular pressure, potentially precipitating angle-closure glaucoma in susceptible individuals. While it is contraindicated in narrow-angle glaucoma, caution is advised even in open-angle glaucoma, with an eye examination recommended prior to initiation and prophylactic measures considered if anatomical risks are present.[15] Protriptyline should be used cautiously in patients with seizure disorders, as it may lower the seizure threshold and increase the risk of convulsions. The lowest effective dose is recommended, with close monitoring for seizure activity, particularly in those with a history of seizures.[18] Elderly patients exhibit increased sensitivity to protriptyline's anticholinergic and sedative effects, necessitating dose adjustments. Therapy should begin at a low dose of 5 mg three times daily (totaling 15 mg/day), with gradual titration and cardiovascular monitoring if the daily dose exceeds 20 mg.[17] Protriptyline should be used with caution in patients with prostatic hypertrophy or a history of urinary retention, as its anticholinergic effects may exacerbate these conditions and lead to acute urinary retention.[19] Use during pregnancy is not recommended unless the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. Animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect, and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans. Limited data exist on its use during pregnancy, and there is a potential for neonatal withdrawal symptoms; it should be avoided if possible, with benefits weighed against risks. During breastfeeding, safe use has not been established, and caution is advised due to potential transmission to the infant; alternative therapies may be preferred.[20]Adverse effects

Common side effects

Protriptyline commonly causes a variety of mild to moderate adverse reactions, many of which stem from its anticholinergic and other receptor-blocking activities, though these are typically manageable with dose adjustments or supportive measures.[4] Anticholinergic effects are particularly prevalent and include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, and urinary retention; among these, dry mouth, constipation, and blurred vision are the most frequently reported.[21][17][4] Central nervous system effects, such as dizziness, headache, and fatigue, occur in a notable proportion of patients and may contribute to reduced daytime functioning if not addressed.[17][4] Gastrointestinal side effects encompass nausea, increased appetite, and weight gain, which can affect patient compliance over time.[17] Sexual dysfunction, manifesting as decreased libido or erectile dysfunction, is a recognized issue with protriptyline and other tricyclic antidepressants.[17][4] Compared to other tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline, protriptyline produces less sedation, rendering it more appropriate for daytime dosing in patients who need to maintain alertness.[5][4]Serious adverse effects

Protriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, is associated with several serious adverse effects that are rare but can be life-threatening and necessitate immediate medical intervention.[4] Cardiac arrhythmias, particularly torsades de pointes, may occur due to QT interval prolongation induced by protriptyline. This risk is heightened in patients over 50 years old, those receiving doses exceeding 20 mg daily, or individuals with preexisting heart conditions such as arrhythmias or prolonged QTc intervals. Additional risk factors include electrolyte imbalances like hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, which can exacerbate QT prolongation and precipitate ventricular arrhythmias. Electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring is recommended, especially at higher doses, to detect these changes early.[4][22][23] Serotonin syndrome represents another critical risk when protriptyline is combined with other serotonergic agents, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Symptoms can include hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability, and seizures, potentially leading to coma or death if untreated. A minimum 14-day washout period is advised before initiating protriptyline after MAOI use to mitigate this interaction.[4][24] Blood dyscrasias, including agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenia, have been reported with protriptyline use, though they are infrequent. These conditions can manifest as severe infections, bleeding tendencies, or fatigue due to low white blood cell or platelet counts. Long-term users should undergo periodic complete blood count (CBC) monitoring to identify early hematologic abnormalities.[4][25][26] Suicidal ideation and behavior carry a black box warning for protriptyline and other antidepressants, particularly in children, adolescents, and young adults under 25 years of age. The risk is elevated during the initial treatment phase or dose adjustments, with symptoms including new or worsening depression, agitation, or attempts at self-harm. Close clinical monitoring for mood and behavioral changes is essential in this population.[18][3][4] Hepatic toxicity from protriptyline is uncommon but can involve elevated liver enzymes, occurring in approximately 10-12% of patients on tricyclic antidepressants, typically in a mild and transient manner. Rare cases of jaundice or more severe hepatic failure have been noted, warranting caution in patients with preexisting liver impairment and periodic liver function tests during prolonged therapy.[5][4]Withdrawal symptoms

Abrupt discontinuation of protriptyline after prolonged use can lead to a withdrawal syndrome characterized by cholinergic rebound symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache.[2][27] These effects arise from rebound excess cholinergic activity following the blockade of muscarinic receptors by the tricyclic antidepressant during treatment.[28] Additionally, noradrenergic symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, insomnia, and flu-like malaise may occur due to adrenergic overdrive.[29][30] The onset of withdrawal symptoms typically occurs within 1-3 days of stopping protriptyline, peaks at 5-7 days, and resolves within 1-2 weeks in most cases.[31][32] This timeline aligns with protriptyline's long half-life of 80 to 200 hours.[4] To prevent withdrawal, the dose should be tapered gradually over 1-4 weeks, for example, reducing from a maximum of 60 mg/day in increments to 10 mg/day before cessation, under medical supervision.[33][34] Risk factors for more severe symptoms include higher daily doses exceeding 40 mg and treatment durations longer than 6 months, as these increase the likelihood of physiological dependence.[27][35]Toxicity and overdose

Symptoms of overdose

Overdose of protriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, manifests through a triad of anticholinergic, cardiovascular, and central nervous system toxicities, which can progress rapidly and lead to life-threatening complications.[36] Anticholinergic effects are prominent and include severe dry mouth, delirium or altered mental status, hyperthermia (fever), mydriasis (dilated pupils), and urinary retention, often accompanied by dry skin and decreased bowel sounds.[36][37] Cardiovascular manifestations typically involve sinus tachycardia, which may evolve into hypotension or hypertension, widened QRS complex on electrocardiogram (with prolongation >100 ms indicating risk of seizures and >160 ms risk of arrhythmias), and ventricular arrhythmias such as tachydysrhythmias, heart block, or torsades de pointes.[36][38] Central nervous system involvement includes seizures, coma, and respiratory depression, with agitation or drowsiness preceding more severe outcomes like profound coma or loss of consciousness.[36][18] Significant symptoms of overdose may occur after ingestion exceeding 10 mg/kg (approximately 700 mg for a 70 kg adult), with potentially life-threatening effects at 10-20 mg/kg. The lowest reported fatal dose is 500 mg, though estimates vary with individual factors and co-ingestants.[36][39][40] Laboratory findings in protriptyline overdose may reveal metabolic acidosis due to lactic acid accumulation from seizures and impaired perfusion, alongside elevated creatine kinase levels from rhabdomyolysis secondary to prolonged seizures or muscle hyperactivity.[41][42]Management of overdose

Management of protriptyline overdose follows protocols established for tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) toxicity, emphasizing rapid stabilization and supportive care to address life-threatening complications such as cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and central nervous system depression.[36] Initial management prioritizes the ABCs—securing the airway, ensuring adequate breathing through ventilation support if needed, and maintaining circulation via intravenous access and fluid resuscitation for hypotension.[15] All patients require continuous cardiac monitoring with serial electrocardiograms (ECGs) to detect conduction abnormalities.[39] Gastrointestinal decontamination is recommended if the patient presents within 2 hours of ingestion and the airway is protected; this involves administration of activated charcoal (1 g/kg orally) to reduce absorption, while emesis induction is contraindicated due to aspiration risk.[36] For patients with altered mental status or coma, orogastric lavage may be considered after airway protection, but only in the early post-ingestion period.[15] In cases of severe cardiotoxicity, such as QRS complex widening greater than 100 ms or ventricular dysrhythmias, intravenous sodium bicarbonate is administered as a 1-2 mEq/kg bolus followed by infusion to achieve a serum pH of 7.45-7.55, which helps overcome sodium channel blockade and stabilize membranes.[39] For refractory hypotension or arrhythmias unresponsive to bicarbonate, intravenous lipid emulsion (20% solution, 1.5 mL/kg bolus followed by infusion) may be considered as an adjunctive therapy in severe cases, based on its reported efficacy in enhancing drug redistribution.[43] Seizures, which may arise from the sodium channel blockade or anticholinergic effects, are primarily treated with benzodiazepines such as lorazepam (2 mg intravenously) or diazepam (5-10 mg intravenously), repeated as needed; phenytoin should be avoided due to its potential to exacerbate conduction delays through additional sodium channel inhibition.[44] If seizures are refractory, phenobarbital (15-20 mg/kg intravenously) or general anesthesia may be required.[36] Supportive measures include active cooling with ice packs or evaporative methods for hyperthermia (core temperature >39°C), often secondary to prolonged seizures or agitation, to prevent organ damage.[45] Urinary retention, a common anticholinergic manifestation, warrants bladder catheterization to alleviate discomfort and reduce agitation if a full bladder is confirmed via ultrasound or palpation.[46] Physostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, may be used cautiously (1-2 mg intravenously over 5 minutes) for severe anticholinergic delirium unresponsive to other therapies, but only after consultation with a poison center due to risks of inducing bradyarrhythmias or seizures in TCA-overdosed patients.[15] Patients should be observed in an intensive care setting for at least 24 hours, as delayed toxicity can occur, and hemodialysis is ineffective given protriptyline's high protein binding and large volume of distribution.[36] Psychiatric evaluation is essential post-stabilization to address underlying suicide risk.[15]Drug interactions

Pharmacokinetic interactions

Protriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, is primarily metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme, and pharmacokinetic interactions often involve alterations in this pathway.[15] Inhibitors of CYP2D6, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like fluoxetine and paroxetine, as well as other agents including quinidine and cimetidine, can significantly elevate protriptyline plasma concentrations by reducing its metabolism.[15][47] This inhibition may result in up to an 8-fold increase in the area under the curve (AUC) for tricyclic antidepressants like protriptyline, depending on the extent of CYP2D6 involvement, necessitating dose reductions of up to 50% or close plasma level monitoring to avoid toxicity.[48] In contrast, enzyme inducers such as carbamazepine accelerate protriptyline metabolism, leading to decreased plasma levels and potentially reduced therapeutic efficacy.[47][24] In such cases, dose increases may be required to maintain effective concentrations, with clinical monitoring recommended to balance efficacy and side effects.[47] Regarding absorption, protriptyline is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, but concurrent use of antacids or drugs with anticholinergic properties may delay gastric emptying and reduce peak plasma concentrations, though specific quantitative impacts for protriptyline remain limited in available data.[15] In patients with renal impairment, protriptyline's elimination half-life (80-200 hours with long-term use) may be affected, warranting cautious dosing and potential adjustments to prevent accumulation, with close monitoring recommended.[49][50] Protriptyline is approximately 92% bound to plasma proteins, primarily albumin, but clinically significant displacement interactions are minimal, as the drug's high extraction ratio limits the impact of binding changes on free concentrations.[51]Pharmacodynamic interactions

Protriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, exhibits several pharmacodynamic interactions primarily through its inhibition of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, as well as its effects on adrenergic and cholinergic systems.[24] These interactions can lead to synergistic or antagonistic effects on neurotransmitter levels and physiological responses when combined with other agents. Concomitant use of protriptyline with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or tranylcypromine, potentiates serotonin and norepinephrine accumulation, substantially increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by hyperthermia, rigidity, and autonomic instability; this combination is contraindicated, and protriptyline should not be initiated within 14 days of discontinuing an MAOI.[47][52] Protriptyline enhances the hypertensive effects of sympathomimetics like epinephrine or norepinephrine by blocking their reuptake into adrenergic neurons, leading to prolonged and intensified alpha-adrenergic stimulation; close monitoring or avoidance of such combinations is recommended to prevent severe hypertension or arrhythmias.[24][47] When combined with alcohol or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants, such as benzodiazepines or opioids, protriptyline produces additive sedation and respiratory depression due to overlapping inhibitory effects on CNS function, necessitating caution and potential dose adjustments in patients requiring these agents.[52][24] Protriptyline antagonizes the hypotensive effects of certain antihypertensives, including guanethidine, by inhibiting the uptake of catecholamines into sympathetic neurons, thereby preventing the depletion of norepinephrine stores that is central to guanethidine's mechanism; alternative antihypertensives may be required.[47][24] Co-administration with QT-prolonging drugs, such as certain antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine) or antiarrhythmics (e.g., quinidine), heightens the risk of ventricular arrhythmias like torsades de pointes through additive prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiograms, warranting ECG monitoring or avoidance in susceptible patients.[52][47]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Protriptyline exerts its primary therapeutic effects through inhibition of monoamine reuptake transporters, with high affinity for the norepinephrine transporter (NET; Ki = 1.41 nM) and moderate affinity for the serotonin transporter (SERT; Ki = 19.6 nM), leading to increased synaptic concentrations of these neurotransmitters; its affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) is substantially weaker (Ki = 2100 nM). The drug also demonstrates antagonist activity at several off-target receptors, including muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (Ki ≈ 25 nM), histamine H1 receptors (Ki ≈ 66 nM), and alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, while exhibiting minimal binding affinity to the 5-HT2A receptor.[53][54] In addition to its monoamine reuptake inhibition, protriptyline blocks voltage-gated sodium channels, which imparts antiarrhythmic effects at low concentrations but can lower the seizure threshold and contribute to cardiovascular toxicity at higher doses.[23] Relative to other tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, protriptyline displays a more selective noradrenergic profile with reduced serotonergic and antihistaminic potency, accounting for its relatively stimulating effects and lower propensity for sedation.[4] By elevating norepinephrine and serotonin levels in the brain, protriptyline enhances monoaminergic neurotransmission to alleviate depressive symptoms; however, its antagonism of muscarinic and histamine receptors underlies common anticholinergic and sedative side effects.[23]Pharmacokinetics

Protriptyline is completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract following oral administration, with a bioavailability of 75–90%.[19] Peak plasma concentrations are typically reached within 8–12 hours after dosing, though this can be delayed due to rapid sequestration into tissues, resulting in relatively low initial plasma levels despite good absorption.[3][19] The drug is widely distributed throughout the body, with a volume of distribution averaging 22 L/kg (range 15–31 L/kg).[55] Approximately 92% of protriptyline is bound to plasma proteins, and it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier to exert central nervous system effects.[47][4] Protriptyline undergoes hepatic metabolism primarily via the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6, with 10–25% of the oral dose subject to first-pass metabolism.[19] This pathway produces several metabolites, including active ones; individuals who are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6 exhibit slower clearance and higher plasma concentrations compared to normal metabolizers.[19][51] Elimination is slow, with a half-life of 54–200 hours, which may be longer (80–200 hours) during long-term use due to saturation of metabolic pathways.[4][56] Approximately 50% of the administered dose is excreted in the urine, predominantly as metabolites, over about 16 days, while fecal excretion accounts for a minor portion via biliary elimination.[19][24] Due to its prolonged half-life, steady-state plasma concentrations are achieved in 7–14 days with daily dosing, though it may take up to a month in some cases.[4] At therapeutic doses of 20–40 mg/day, steady-state plasma levels typically range from 70–260 ng/mL, with higher variability observed in poor CYP2D6 metabolizers.[56]Chemical properties

Molecular structure

Protriptyline possesses the IUPAC name 3-(5H-dibenzo[a,d][57]annulen-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine.[58] This nomenclature reflects its tricyclic core consisting of two benzene rings fused to a central seven-membered cycloheptene ring, with a propan-1-amine side chain bearing an N-methyl substituent attached at the 5-position of the central ring.[59] As a dibenzocycloheptene derivative, protriptyline belongs to the class of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and is classified as a secondary amine due to the single methyl group on the terminal nitrogen atom.[24] The key structural features include the unsaturated central seven-membered ring, which distinguishes it from many other TCAs, and the flexible propylamine side chain that facilitates its interaction with biological targets.[60] Protriptyline is achiral, lacking defined stereocenters and exhibiting no optical isomers.[61] It shares structural similarities with amitriptyline, another dibenzocycloheptene TCA, but features a distinct attachment of the side chain directly to the saturated carbon at position 5 rather than an exocyclic double bond, contributing to differences in potency.[62]Physical and chemical properties

Protriptyline, in its free base form, has the molecular formula C19H21N and a molecular weight of 263.38 g/mol, while the hydrochloride salt form is C19H22ClN with a molecular weight of 299.84 g/mol.[24][22] The hydrochloride salt appears as a white to off-white or yellowish crystalline powder.[15][63] It exhibits good solubility characteristics suitable for pharmaceutical formulation: the hydrochloride salt is very soluble in water (≥ 500 mg/mL) and chloroform, and freely soluble in alcohol (approximately 250 mg/mL), but practically insoluble in ether. The pKa value for the basic nitrogen is 10.54, reflecting its weakly basic nature.[22][24] Protriptyline hydrochloride demonstrates reasonable stability under standard conditions, including light; necessitating storage in tight, light-resistant containers at controlled room temperature (20–25°C) protected from excessive moisture.[22][2][19] With a logP value of 4.7, protriptyline is highly lipophilic, a property that supports its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier for central nervous system effects.[24]Development and history

Discovery and synthesis

Protriptyline was developed by Merck & Co. in the early 1960s as part of efforts to optimize tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) for enhanced therapeutic efficacy.[64] Researchers at Merck sought to modify the dibenzocycloheptene scaffold to improve noradrenergic reuptake inhibition while minimizing sedative side effects observed in earlier TCAs like imipramine.[65] This structural refinement aimed to produce a more activating antidepressant profile suitable for patients requiring stimulation rather than sedation.[4] The compound, chemically known as 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine, was first patented by Merck in 1962 under US Patent 3,205,264, which detailed a key process for its preparation.[64] The patent describes a hydrogenation method using catalysts such as Raney nickel to reduce the aminopropylidene intermediate, yielding the saturated side chain essential for its activity.[64] This step ensured the stability and bioavailability of the final molecule as an acid addition salt, typically the hydrochloride form.[64] The initial literature disclosure appeared in 1964 in a paper introducing protriptyline hydrochloride (Triptil) as a new antidepressant.[66] A seminal paper in 1968 examined structure-activity relationships (SAR) among dibenzocycloheptene-5-propylamines for tetrabenazine-antagonizing activity, a model for antidepressant potential, in which protriptyline demonstrated potent antagonism, highlighting the benefits of the N-methyl substitution on the propylamine side chain for noradrenergic selectivity.[67] Synthesis of protriptyline begins with dibenzosuberone, the core tricyclic ketone, which undergoes a Mannich reaction with formaldehyde and methylamine to introduce the 3-(methylamino)propyl group.[68] The resulting Mannich base is then dehydrated to form an enamine intermediate, followed by selective reduction to afford the target compound.[68] This sequence, optimized during Merck's research, allowed efficient production of the drug while preserving the seven-membered central ring's conformational flexibility, which contributes to its pharmacological profile.[64]Clinical development and approval

Protriptyline's clinical development began with preclinical investigations in the mid-1960s, where animal studies demonstrated its antidepressant efficacy in rodent models of depression, showing potentiation of neurotransmitter activity similar to other tricyclic antidepressants.[66] These early findings supported progression to human trials, with phase I studies evaluating safety and tolerability in small cohorts shortly thereafter. Key clinical trials in the 1960s established protriptyline's efficacy for major depressive disorder (MDD). A double-blind study compared protriptyline to imipramine and amitriptyline in outpatients, with a 65% response rate at doses up to 60 mg daily over 4-6 weeks.[69] Additional controlled trials in the same decade confirmed these results, demonstrating faster onset of action compared to established tricyclics like amitriptyline in outpatient settings.[70] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved protriptyline in 1967 for the treatment of MDD under the brand name Vivactil, marking its initial marketing in the United States by Merck.[71] Post-approval, reports from the 1970s explored its off-label use in sleep apnea, with studies showing reduced apnea frequency and improved alertness in patients treated with 10-20 mg nightly.[72] In 2007, the FDA added a black box warning to protriptyline's labeling, along with all antidepressants, highlighting increased risk of suicidality in children, adolescents, and young adults during initial treatment phases.[73] While the branded Vivactil formulations were discontinued, generic versions approved by the FDA in 2010 and 2012 ensure continued availability as of 2025.[74]Society and culture

Generic and brand names

Protriptyline is the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) for the active substance, while protriptyline hydrochloride serves as the United States Adopted Name (USAN) for its salt form commonly used in pharmaceutical preparations.[24][22] The drug is most widely recognized under the brand name Vivactil, originally developed and marketed by Merck & Co. as the primary commercial product in the United States.[75] In various international markets, it has been sold under other brand names, including Triptil and Concordin, particularly in Europe and other regions.[76][49] Generic protriptyline hydrochloride became available in the United States following the approval of an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) by Epic Pharma on November 19, 2012, with additional approvals from manufacturers such as Sigmapharm Laboratories in subsequent years.[74] These generic formulations are offered in tablet strengths of 5 mg and 10 mg, mirroring the original branded product.[1] Protriptyline is exclusively formulated as immediate-release oral tablets, with no extended-release or alternative dosage forms approved for clinical use.[25][2]Legal status and availability

Protriptyline is classified as a prescription-only medication in the United States and is not designated as a controlled substance under the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) scheduling system.[2] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved protriptyline in 1967 for the treatment of major depressive disorder, positioning it as a second-line tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) due to the availability of safer first-line alternatives, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have fewer anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects.[4] [23] Generic formulations are widely available from manufacturers including Epic Pharma LLC and Sigmapharm Laboratories LLC.[74] Internationally, protriptyline has limited availability; it is approved in Canada but was cancelled from the post-market status in 2001, discontinued in the United Kingdom in 2000, and discontinued in several European Union countries since the early 2000s owing to the preference for newer antidepressants. As of 2025, it remains available only in the United States.[4] [77] Occasional supply shortages have occurred in the past, though as of 2025, protriptyline is not listed among active drug shortages by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP).[78] In the United States, the cost of generic protriptyline typically ranges from $20 to $50 for a 30-tablet supply of 10 mg tablets, varying by pharmacy and discount programs.[79]References

- Jun 4, 2025 · Usual Adult Dose for Depression: 15 to 40 mg orally per day divided into three or four doses. Comments: Use: Treatment of symptoms of mental depression.