Recent from talks

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Contribute something

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Prolintane.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prolintane

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Catovit, Katovit, Promotil, Villescon |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intranasal, rectal |

| Drug class | Stimulant; Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.077 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H23N |

| Molar mass | 217.356 g·mol−1 |

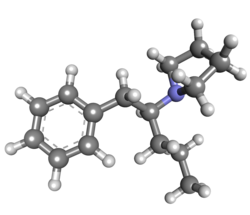

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 133 °C (271 °F) |

| Boiling point | 153 °C (307 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Prolintane is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant[2] and norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) of the phenylalkylpyrrolidine family developed in the 1950s.[3] Being an amphetamine derivative, it is closely related in chemical structure to other drugs such as pyrovalerone, MDPV, and propylhexedrine, and has a similar mechanism of action.[4] Many cases of prolintane abuse have been reported.[5]

Under the brand name Katovit, prolintane was commercialized by the Spanish pharmaceutical company FHER until 2001. It was most often used by students and workers as a stimulant to provide energy and increase alertness and concentration.[medical citation needed]

See also

[edit]- α-PVP (β-ketone-prolintane, prolintanone)

- Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)

- Pyrovalerone (Centroton, Thymergix)

- Phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP)

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Hollister LE, Gillespie HK (March–April 1970). "A new stimulant, prolintane hydrochloride, compared with dextroamphetamine in fatigued volunteers". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and the Journal of New Drugs. 10 (2): 103–9. doi:10.1177/009127007001000205. PMID 4392006.

- ^ GB Patent 807835

- ^ Nicholson AN, Stone BM, Jones MM (November 1980). "Wakefullness and reduced rapid eye movement sleep: studies with prolintane and pemoline". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (5): 465–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01790.x. PMC 1430138. PMID 7437258.

- ^ Kyle PB, Daley WP (September 2007). "Domestic abuse of the European rave drug prolintane". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 31 (7): 415–8. doi:10.1093/jat/31.7.415. PMID 17725890.

Prolintane

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Prolintane is a synthetic central nervous system (CNS) stimulant chemically classified as a member of the amphetamines, with the molecular formula C₁₅H₂₃N and a structure featuring a phenylalkylpyrrolidine backbone.[1] It functions primarily as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), blocking the uptake of these neurotransmitters into neurons to enhance their synaptic availability and produce alerting and energizing effects.[2]

Developed in the 1950s, prolintane has been investigated in clinical trials up to phase II for potential therapeutic applications, including as an analeptic agent to combat fatigue in individuals without underlying disease.[1][3] Its pharmacological profile closely resembles that of d-amphetamine, acting as a sympathomimetic amine that promotes wakefulness, reduces rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and increases alertness.[4][5] Common side effects include insomnia, nervousness, irritability, headache, and dry mouth, with potential risks of cardiovascular strain in susceptible individuals.[4]

Despite limited approved medical indications, prolintane has seen recreational use, particularly in Europe as a "rave drug" for its euphoric and performance-enhancing properties, leading to documented cases of abuse and prompting calls for careful monitoring due to its demonstrated reinforcing effects in animal models.[4][6] It remains an experimental small-molecule drug with one investigational indication noted in pharmacological databases, and its regulatory status varies by region, often requiring prescription where available.[1]

Chemistry

Structure and properties

Prolintane has the molecular formula C₁₅H₂₃N and a molar mass of 217.35 g/mol.[1] Its IUPAC name is 1-(1-phenylpentan-2-yl)pyrrolidine, with synonyms including prolintane and trade names such as Catovit, Katovit, Promotil, and Villescon.[1][7] Prolintane is classified as an amphetamine derivative within the phenylalkylpyrrolidine family and shares structural similarities with pyrovalerone, MDPV, and propylhexedrine. The molecule features a phenethylamine core with a pyrrolidine ring substituted at the alpha carbon and a pentyl side chain extending from that position.[8][9] Prolintane is a colorless oil. Key physical properties include a boiling point of 153 °C under reduced pressure. Prolintane shows slight solubility in organic solvents like chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol.[10][11] The molecule contains a chiral center at the alpha carbon attached to the pyrrolidine group but is generally employed as a racemic mixture, with no particular enantiomer specified in most formulations.[12]Synthesis

The primary synthesis route for prolintane involves reductive amination of 1-phenylpentan-2-one with pyrrolidine to form the corresponding imine intermediate, followed by selective reduction using agents such as sodium cyanoborohydride in methanol or catalytic hydrogenation with palladium on carbon under hydrogen gas. This method provides the target secondary amine in moderate to good yields, typically 60-80%, depending on reaction conditions and scale. Alternative synthetic approaches include variants of the Mannich reaction, where a one-pot Mannich-Barbier process couples a ketone, formaldehyde, and pyrrolidine in the presence of allyl halides or Grignard reagents to construct the carbon framework, though these are more commonly applied to prolintane analogs. A more recent four-step method starts from phenylacetyl chloride, proceeding through ester formation, Grignard addition to generate a secondary alcohol, mesylation of the hydroxyl group, and nucleophilic substitution with pyrrolidine to afford prolintane in an overall yield of approximately 40%. Historical synthesis efforts date to the 1950s, when prolintane was developed by pharmaceutical researchers at Thomae (a division of Boehringer Ingelheim), with the initial reductive amination route patented in Germany (DE 1088962) in 1956 and in the UK (GB 807835) in 1959.[13] The Spanish company FHER, which commercialized prolintane as Katovit, secured a related process patent (ES 358367) in 1970, likely adapting these methods for industrial production. These early protocols emphasized scalability while minimizing toxic reagents like cyanide used in contemporaneous Strecker variants. Synthesized prolintane is characterized for purity using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to confirm the proton and carbon environments, infrared (IR) spectroscopy to identify key functional group absorptions such as C-H stretches around 2800-3000 cm⁻¹, and chromatographic techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to assess impurity levels, typically achieving >95% purity post-purification. This synthesis shares conceptual similarities with routes for amphetamine analogs, relying on amine-carbonyl condensations for stereocontrolled carbon-nitrogen bond formation.Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Prolintane functions primarily as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), exerting its stimulant effects by blocking the dopamine transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET). This inhibition prevents the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, leading to elevated synaptic levels of these catecholamines in key brain regions such as the striatum and prefrontal cortex.[14] In vitro studies demonstrate potent uptake inhibition, with IC50 values of 0.043 μM at human DAT (hDAT) and 0.059 μM at human NET (hNET), underscoring its efficacy in modulating noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.[14] Prolintane exhibits weaker activity at the serotonin transporter (SERT), with an IC50 of approximately 28.6 μM for human SERT (hSERT), resulting in negligible serotonergic reuptake inhibition under typical physiological conditions.[14] However, at hSERT, prolintane behaves as a substrate rather than a pure inhibitor, inducing serotonin efflux and ionic currents, a property that confers hybrid characteristics reminiscent of amphetamine-like releasing agents.[14] This substrate activity is species-dependent, being more pronounced in human than rat SERT, with no efflux observed in rat synaptosomes.[14] In comparison to other stimulants, prolintane's mechanism aligns closely with reuptake inhibitors like methylphenidate and cocaine, primarily elevating extracellular dopamine via DAT blockade without significant vesicular monoamine releaser effects at DAT or NET.[6] Unlike amphetamines, which predominantly promote monoamine release from vesicles, prolintane lacks substantial releasing activity at catecholamine transporters, though its SERT substrate profile introduces a partial amphetamine-like element.[14] It does not exhibit notable monoamine oxidase inhibition, distinguishing it from certain antidepressants or older stimulants.[6] The phenylalkylpyrrolidine core of prolintane facilitates competitive binding to the substrate sites of DAT and NET, enabling its reuptake inhibitory profile.[14] Microdialysis studies confirm that systemic administration increases striatal dopamine levels, consistent with DAT inhibition and supporting its role in the mesolimbic reward pathway.[6]Pharmacokinetics

Prolintane is administered orally in humans and is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with metabolites detectable in urine following administration.[15] The drug undergoes hepatic metabolism primarily mediated by cytochrome P-450 enzymes, leading to the formation of several metabolites, including oxoprolintane (a lactam derivative via pyrrolidine ring oxidation) and p-hydroxyprolintane.[16][17] In vitro studies using rabbit liver microsomes demonstrate rapid conversion of prolintane to oxoprolintane under aerobic conditions in the presence of NADPH, while rat liver preparations metabolize it more slowly.[17][18] In rats, following intraperitoneal administration of 50 mg/kg [³H]-prolintane, approximately 57% of the administered radioactivity is excreted in urine over 48 hours, with identified metabolites including a pyrrolidine ring-opened derivative (15% of dose) and p-hydroxyprolintane (5% of dose); traces of unchanged prolintane and oxoprolintane are also present.[19] Elimination occurs primarily via the renal route, with urinary excretion as the dominant pathway in both animal models and humans.[19][15] Metabolic profiles differ between enantiomers in humans, with the R-(+)-enantiomer showing lower urinary excretion of unchanged drug compared to the S-(-)-enantiomer, indicating enantioselective metabolism.[15] These pharmacokinetic properties contribute to the sustained central nervous system stimulant effects observed with prolintane.[6]Medical uses

Therapeutic indications

Prolintane has been used for the treatment of narcolepsy, excessive daytime sleepiness, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and fatigue-related disorders, particularly in regions such as Europe, Africa, and Australia. Its use as a central nervous system stimulant targeted conditions involving impaired alertness and concentration, serving as an adjunct therapy for asthenia or fatigue-related disorders in some contexts.[20] Efficacy studies demonstrated prolintane's ability to promote wakefulness through alterations in sleep architecture, as observed in electroencephalographic (EEG) evaluations. For instance, administration of 15 mg and 30 mg doses reduced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep by delaying its onset and decreasing its duration during the first three hours of sleep, while increasing overall awakenings and alertness. In comparative research with fatigued volunteers, prolintane at 40 mg produced effects akin to dextroamphetamine, including decreased drowsiness, heightened nervousness, and improved mood, albeit with milder intensity.[2] Historically, prolintane was prescribed to enhance energy, alertness, and concentration in students and workers facing debility or fatigue, reflecting its role as a mild sympathomimetic agent for non-pathological lethargy. However, due to concerns over abuse potential, it has been withdrawn from many markets since the 1990s and is rarely considered a first-line treatment. As of 2025, its therapeutic availability is highly limited. It is classified under psychostimulants and nootropics in some databases but remains investigational with no approval in major markets like the US, and is prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency.[8][21]Dosage and administration

Prolintane is administered orally in clinical settings, with the standard dosage for adults ranging from 10 to 30 mg per day, typically divided into one or two doses to maintain steady effects while minimizing side effects such as insomnia.[22] Doses in this range have been shown to induce dose-dependent psychostimulant effects in prior clinical studies.[22] For example, single doses of 15 mg and 30 mg have been used to evaluate its impact on wakefulness and rapid eye movement sleep reduction.[23] Administration is recommended in the morning to align with the drug's pharmacokinetic profile, which supports daytime alertness without interfering with nighttime rest.[24] It may be taken with food to reduce potential gastrointestinal upset, and patients should be monitored for tolerance, with dosage adjustments based on individual response. Gradual withdrawal is advised after prolonged use to prevent rebound effects.[25] Lower doses, such as 10-25 mg per day, are suggested for elderly patients or those with hepatic impairment to account for reduced clearance, though specific titration should be guided by clinical monitoring.[25] In pediatric cases, where applicable, growth parameters like weight and height must be closely tracked during treatment.[25]Adverse effects

Common side effects

Prolintane, when administered at therapeutic doses, commonly produces mild to moderate sympathomimetic effects, including insomnia, nervousness, tachycardia, dry mouth, and appetite suppression (anorexia).[25][26] These effects arise from its stimulant properties and are frequently reported in clinical observations of fatigued volunteers.[27] Less frequent adverse reactions include headache, gastrointestinal upset such as abdominal cramps, as well as mild irritability and restlessness.[25] Sweating, dizziness, and tremor may also occur, particularly with higher doses within the therapeutic range.[25] For instance, clinical reports have noted tension in subjects receiving 40 mg doses.[27] Management typically involves dose reduction to minimize intensity and supportive measures like hydration to alleviate symptoms such as dry mouth.[25] These reactions share similarities with those of other central nervous system stimulants.Toxicity and dependence

Prolintane overdose can lead to severe symptoms including hallucinations, psychosis, and potentially fatal outcomes due to its sympathomimetic properties.[26] In animal models, the oral LD50 in mice is 257 mg/kg, indicating moderate acute toxicity compared to other stimulants.[28] Common overdose manifestations in humans, extrapolated from case reports of recreational abuse, include hyperthermia, seizures, and cardiovascular collapse, akin to those observed in amphetamine-like intoxications.[26] Prolintane exhibits moderate abuse liability primarily through reinforcement of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, as it increases extracellular dopamine levels in the striatum.[29] A 2022 rodent study demonstrated rewarding effects via conditioned place preference at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg, and reinforcing properties through intravenous self-administration, where mice preferred prolintane (4 mg/kg/infusion) over saline, pressing active levers more frequently.[29] Withdrawal following chronic use typically involves fatigue and depression, consistent with dopamine reuptake inhibitor cessation syndromes.[30] Chronic prolintane use poses risks of cardiovascular strain, including potential QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias, as the possibility of hERG potassium channel involvement cannot be excluded in preclinical cardiac models.[31] Psychosis has been reported in overdose scenarios linked to European rave contexts, where prolintane was abused for its amphetamine-like euphoria.[26] There is no specific antidote for prolintane overdose; management relies on supportive care, including cooling for hyperthermia, seizure control, and cardiovascular monitoring. Benzodiazepines are recommended to address agitation and seizures.[32]History

Development

Prolintane was synthesized in the 1950s as part of research into amphetamine analogs aimed at developing central nervous system stimulants with sympathomimetic properties. It emerged from structural modifications to earlier compounds like 1-phenyl-2-pyrrolidin-1-ylpropane (MPEP), where the α-methyl group was extended to an n-propyl chain to enhance stimulant effects.[33] The compound was patented in 1959 by Thomae, a predecessor to Boehringer Ingelheim, for applications in treating central nervous system disorders.[33] Boehringer Ingelheim subsequently commercialized prolintane in Europe under the brand name Villescon starting in the early 1960s, marketing it as a mild psychostimulant for conditions such as fatigue and asthenia.[34] In Spain, the pharmaceutical company FHER introduced it as Katovit in the 1960s for indications including asthenia. It was also prescribed in other regions such as South Africa and Australia.[20] Initial patents emphasized its potential for enhancing alertness and concentration in therapeutic settings.[33] Reports of recreational abuse, particularly in rave scenes by the early 2000s, prompted concerns over its potential for dependence and misuse.[20] FHER discontinued Katovit in Spain around the early 2000s.Clinical research

Early clinical research on prolintane focused on its stimulant effects in comparison to established drugs like dextroamphetamine. In a double-blind study involving fatigued volunteers, Hollister and Gillespie (1970) administered prolintane hydrochloride (up to 30 mg) and found it produced similar increases in alertness and performance on cognitive tasks as dextroamphetamine (10 mg), but with notably less euphoria and subjective stimulation reported by participants.[27] Subsequent studies explored prolintane's impact on sleep and wakefulness. Nicholson et al. (1980) conducted a double-blind trial in healthy male subjects, administering prolintane at doses of 15 mg and 30 mg, which significantly increased wakefulness, delayed the onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and reduced total REM duration while showing EEG patterns indicative of heightened arousal and reduced drowsiness.[23] More recent preclinical research has examined prolintane's potential for abuse. A 2022 study by Lee et al. using rodent models demonstrated that prolintane (1-10 mg/kg) supported self-administration behaviors and elicited conditioned place preference, suggesting reinforcing effects comparable to those of amphetamine-like stimulants.[20] Human clinical trials on prolintane have been limited since the early 2000s, largely due to increasing regulatory restrictions stemming from concerns over misuse as a recreational drug. According to pharmacological databases, prolintane remains in Phase II investigational status with no major post-2000 human efficacy or safety trials reported.[1]Society and culture

Legal status

Prolintane is not scheduled under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances or other international drug control treaties, resulting in regulatory status that varies significantly by country. In the United States, prolintane is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any medical use and is not listed as a controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, classifying it as an unapproved new drug subject to import and distribution restrictions. In Europe, its availability has been restricted in several markets; for example, it was marketed in Spain under the brand name Katovit until its withdrawal in 2001 due to safety concerns. In Germany, prolintane is classified as a prescription-only medicine under Anlage 1 of the Arzneimittelverschreibungsverordnung (AMVV).[35] In Australia, prolintane is classified as Schedule 4 (prescription only). In Brazil, it is listed as Class B1 (psychoactive drugs). Prolintane is monitored in sports as a prohibited substance by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), falling under the category of stimulants banned in competition.Recreational use

Prolintane has been documented in recreational contexts primarily within European rave scenes during the early 2000s. In 2002, toxicological analyses identified its use at parties in south-western France, where participants consumed orange-coated tablets containing 200 mg of prolintane, often sourced from Spain and combined with vitamins like ascorbic acid. These tablets were sold cheaply at approximately 1.93 € for a pack of 20, facilitating widespread availability for non-medical consumption.[36] Recreational administration typically occurs orally via tablets to achieve a rapid onset of stimulant effects, though intranasal insufflation has been reported in some stimulant-using communities for quicker euphoria. Users commonly take doses ranging from 25-50 mg to obtain an energy boost and mild euphoric sensations, enabling prolonged physical activity such as dancing without the severe comedown associated with stronger amphetamines. Motivations center on heightened alertness, increased endurance, and subtle mood elevation, positioning prolintane as a functional alternative in party settings.[37][6] Despite these patterns, prolintane remains rare compared to more prevalent stimulants like MDMA or cocaine, with documented cases limited to specific incidents, including pre-2001 availability and abuse in Spain. Its lower abuse liability, evidenced by moderate reinforcing effects in preclinical models, contributes to infrequent compulsive redosing relative to MDMA. Occasional non-rave use includes students employing it as a nootropic for enhanced focus during study sessions. Legal restrictions in many regions have further curtailed its recreational prevalence.[26][6]References

- https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Prolintane