Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multiview orthographic projection

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Graphical projection |

|---|

|

In technical drawing and computer graphics, a multiview projection is a technique of illustration by which a standardized series of orthographic two-dimensional pictures are constructed to represent the form of a three-dimensional object. Up to six pictures of an object are produced (called primary views), with each projection plane parallel to one of the coordinate axes of the object. The views are positioned relative to each other according to either of two schemes: first-angle or third-angle projection. In each, the appearances of views may be thought of as being projected onto planes that form a six-sided box around the object. Although six different sides can be drawn, usually three views of a drawing give enough information to make a three-dimensional object.

These three views are known as front view (also elevation view), top view or plan view and end view (also profile view or section view).

When the plane or axis of the object depicted is not parallel to the projection plane, and where multiple sides of an object are visible in the same image, it is called an auxiliary view.

Overview

[edit]

To render each such picture, a ray of sight (also called a projection line, projection ray or line of sight) towards the object is chosen, which determines on the object various points of interest (for instance, the points that are visible when looking at the object along the ray of sight); those points of interest are mapped by an orthographic projection to points on some geometric plane (called a projection plane or image plane) that is perpendicular to the ray of sight, thereby creating a 2D representation of the 3D object.

Customarily, two rays of sight are chosen for each of the three axes of the object's coordinate system; that is, parallel to each axis, the object may be viewed in one of 2 opposite directions, making for a total of 6 orthographic projections (or "views") of the object:[1]

- Along a vertical axis (often the y-axis): The top and bottom views, which are known as plans (because they show the arrangement of features on a horizontal plane, such as a floor in a building).

- Along a horizontal axis (often the z-axis): The front and back views, which are known as elevations (because they show the heights of features of an object such as a building).

- Along an orthogonal axis (often the x-axis): The left and right views, which are also known as elevations, following the same reasoning.

These six planes of projection intersect each other, forming a box around the object, the most uniform construction of which is a cube; traditionally, these six views are presented together by first projecting the 3D object onto the 2D faces of a cube, and then "unfolding" the faces of the cube such that all of them are contained within the same plane (namely, the plane of the medium on which all of the images will be presented together, such as a piece of paper, or a computer monitor, etc.). However, even if the faces of the box are unfolded in one standardized way, there is ambiguity as to which projection is being displayed by a particular face; the cube has two faces that are perpendicular to a ray of sight, and the points of interest may be projected onto either one of them, a choice which has resulted in two predominant standards of projection:

- First-angle projection: In this type of projection, the object is imagined to be in the first quadrant. Because the observer normally looks from the right side of the quadrant to obtain the front view, the objects will come in between the observer and the plane of projection. Therefore, in this case, the object is imagined to be transparent, and the projectors are imagined to be extended from various points of the object to meet the projection plane. When these meeting points are joined in order on the plane they form an image, thus in the first angle projection, any view is so placed that it represents the side of the object away from it. First angle projection is often used throughout parts of Europe so that it is often called European projection.

- Third-angle projection: In this type of projection, the object is imagined to be in the third quadrant. Again, as the observer is normally supposed to look from the right side of the quadrant to obtain the front view, in this method, the projection plane comes in between the observer and the object. Therefore, the plane of projection is assumed to be transparent. The intersection of this plan with the projectors from all the points of the object would form an image on the transparent plane.

Primary views

[edit]Multiview projections show the primary views of an object, each viewed in a direction parallel to one of the main coordinate axes. These primary views are called plans and elevations. Sometimes they are shown as if the object has been cut across or sectioned to expose the interior: these views are called sections.

Plan

[edit]

A plan is a view of a 3-dimensional object seen from vertically above (or sometimes below[citation needed]). It may be drawn in the position of a horizontal plane passing through, above, or below the object. The outline of a shape in this view is sometimes called its planform, for example with aircraft wings.

The plan view from above a building is called its roof plan. A section seen in a horizontal plane through the walls and showing the floor beneath is called a floor plan.

Elevation

[edit]

Elevation is the view of a 3-dimensional object from the position of a vertical plane beside an object. In other words, an elevation is a side view as viewed from the front, back, left or right (and referred to as a 'front elevation', '[left/ right] side elevation', and a 'rear elevation').

An elevation is a common method of depicting the external configuration and detailing of a 3-dimensional object in two dimensions. Building façades are shown as elevations in architectural drawings and technical drawings.

Elevations are the most common orthographic projection for conveying the appearance of a building from the exterior. Perspectives are also commonly used for this purpose. A building elevation is typically labeled in relation to the compass direction it faces; the direction from which a person views it. E.g. the North Elevation of a building is the side that most closely faces true north on the compass.[2]

Interior elevations are used to show details such as millwork and trim configurations.

In the building industry elevations are non-perspective views of the structure. These are drawn to scale so that measurements can be taken for any aspect necessary. Drawing sets include front, rear, and both side elevations. The elevations specify the composition of the different façades of the building, including ridge heights, the positioning of the final fall of the land, exterior finishes, roof pitches, and other architectural details.

Developed elevation

[edit]A developed elevation is a variant of a regular elevation view in which several adjacent non-parallel sides may be shown together as if they have been unfolded. For example, the north and west views may be shown side-by-side, sharing an edge, even though this does not represent a proper orthographic projection.

Section

[edit]A section, or cross-section, is a view of a 3-dimensional object from the position of a plane through the object.

A section is a common method of depicting the internal arrangement of a 3-dimensional object in two dimensions. It is often used in technical drawing and is traditionally crosshatched. The style of crosshatching often indicates the type of material the section passes through.

With computed axial tomography, computers construct cross-sections from x-ray data.

-

A 3-D view of a beverage-can stove with a cross-section in yellow

-

A 2-D cross-sectional view of a compression seal fitting

-

Cutaway of a Porsche 996

-

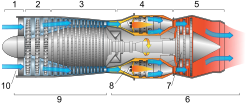

Cross-section of a jet engine

-

Section view in architectural design

-

Cryosection of a human head

Auxiliary views

[edit]An auxiliary view or pictorial, is an orthographic view that is projected into any plane other than one of the six primary views.[3] These views are typically used when an object has a surface in an oblique plane. By projecting into a plane parallel with the oblique surface, the true size and shape of the surface are shown. Auxiliary views are often drawn using isometric projection.

Multiviews

[edit]This article needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. (April 2014) |

Quadrants in descriptive geometry

[edit]

Modern orthographic projection is derived from Gaspard Monge's descriptive geometry.[4] Monge defined a reference system of two viewing planes, horizontal H ("ground") and vertical V ("backdrop"). These two planes intersect to partition 3D space into four quadrants, which he labeled:

- I: above H, in front of V

- II: above H, behind V

- III: below H, behind V

- IV: below H, in front of V

These labels are the same as used in 2D planar geometry (), as seen from infinitely far to the "left", taking H and V to be the X-axis and Y-axis, respectively.

The 3D object of interest is then placed into either quadrant I or III (equivalently, the position of the intersection line between the two planes is shifted), obtaining first- and third-angle projections, respectively. Quadrants II and IV are also mathematically valid, but their use would result in one view "true" and the other view "flipped" by 180° through its vertical centerline, which is too confusing for technical drawings. (In cases where such a view is useful, e.g. a ceiling viewed from above, a reflected view is used, which is a mirror image of the true orthographic view.)

Monge's original formulation uses two planes only and obtains the top and front views only. The addition of a third plane to show a side view (either left or right) is a modern extension. The terminology of quadrant is a mild anachronism, as a modern orthographic projection with three views corresponds more precisely to an octant of 3D space.

First-angle projection

[edit]

In first-angle projection, the object is conceptually located in quadrant I, i.e. it floats above and before the viewing planes, the planes are opaque, and each view is pushed through the object onto the plane furthest from it. (Mnemonic: an "actor on a stage".) Extending to the 6-sided box, each view of the object is projected in the direction (sense) of sight of the object, onto the (opaque) interior walls of the box; that is, each view of the object is drawn on the opposite side of the box. A two-dimensional representation of the object is then created by "unfolding" the box, to view all of the interior walls. This produces two plans and four elevations. A simpler way to visualize this is to place the object on top of an upside-down bowl. Sliding the object down the right edge of the bowl reveals the right side view.

-

An image of an object in a box

-

The same image, with views of the object projected in the direction of sight onto walls using first-angle projection

-

Similar image showing the box unfolding from around the object

-

Image showing orthographic views located relative to each other in accordance with first-angle projection

Third-angle projection

[edit]

In third-angle projection, the object is conceptually located in quadrant III, i.e. it is positioned below and behind the viewing planes, the planes are transparent, and each view is pulled onto the plane closest to it. Using the six-sided viewing box, each view of the object is projected opposite to the direction (sense) of sight, onto the (transparent) exterior walls of the box; that is, each view of the object is drawn on the corresponding side of the box. The box is then unfolded to view all of its exterior walls.

Below is the construction of third-angle projections of the same object as above. The individual views are the same, just arranged differently.

Additional information

[edit]

First-angle projection is as if the object were sitting on the paper and, from the face (front) view, it is rolled to the right to show the left side or rolled up to show its bottom. It is standard throughout Europe and Asia (excluding Japan). First-angle projection was widely used in the UK, but during World War II, British drawings sent to be manufactured in the USA, such as of the Rolls-Royce Merlin, had to be drawn in third-angle projection before they could be produced, e.g., as the Packard V-1650 Merlin. This meant that some British companies completely adopted third angle projection. BS 308 (Part 1) Engineering Drawing Practice, gave the option of using both projections, but generally, every illustration (other than the ones explaining the difference between first and third-angle) was done in first-angle. After the withdrawal of BS 308 in 1999, BS 8888 offered the same choice since it referred directly to ISO 5456-2, Technical drawings – Projection methods – Part 2: Orthographic representations.

Third-angle is as if the object were a box to be unfolded. If we unfold the box so that the front view is in the center of the two arms, then the top view is above it, the bottom view is below it, the left view is to the left, and the right view is to the right. It is standard in the USA (ASME Y14.3-2003 specifies it as the default projection system), Japan (JIS B 0001:2010 specifies it as the default projection system), Canada, and Australia (AS1100.101 specifies it as the preferred projection system).

Both first-angle and third-angle projections result in the same 6 views; the difference between them is the arrangement of these views around the box.

Symbol

[edit]

A great deal of confusion has ensued in drafting rooms and engineering departments when drawings are transferred from one convention to another. On engineering drawings, the projection is denoted by an international symbol representing a truncated cone in either first-angle or third-angle projection, as shown by the diagram on the right.

The 3D interpretation is a solid truncated cone, with the small end pointing toward the viewer. The front view is, therefore, two concentric circles. The fact that the inner circle is drawn with a solid line instead of dashed identifies this view as the front view, not the rear view. The side view is an isosceles trapezoid.

- In first-angle projection, the front view is pushed back to the rear wall, and the right side view is pushed to the left wall, so the first-angle symbol shows the trapezoid with its shortest side away from the circles.

- In third-angle projection, the front view is pulled forward to the front wall, and the right side view is pulled to the right wall, so the third-angle symbol shows the trapezoid with its shortest side towards the circles.

Multiviews without rotation

[edit]Orthographic multiview projection is derived from the principles of descriptive geometry and may produce an image of a specified, imaginary object as viewed from any direction of space. Orthographic projection is distinguished by parallel projectors emanating from all points of the imaged object and which intersect of projection at right angles. Above, a technique is described that obtains varying views by projecting images after the object is rotated to the desired position.

Descriptive geometry customarily relies on obtaining various views by imagining an object to be stationary and changing the direction of projection (viewing) in order to obtain the desired view.

See Figure 1. Using the rotation technique above, note that no orthographic view is available looking perpendicularly at any of the inclined surfaces. Suppose a technician desired such a view to, say, look through a hole to be drilled perpendicularly to the surface. Such a view might be desired for calculating clearances or for dimensioning purposes. To obtain this view without multiple rotations requires the principles of Descriptive Geometry. The steps below describe the use of these principles in third angle projection.

- Fig.1: Pictorial of the imaginary object that the technician wishes to image.

- Fig.2: The object is imagined behind a vertical plane of projection. The angled corner of the plane of projection is addressed later.

- Fig.3: Projectors emanate parallel from all points of the object, perpendicular to the plane of projection.

- Fig.4: An image is created thereby.

- Fig.5: A second, horizontal plane of projection is added, perpendicular to the first.

- Fig.6: Projectors emanate parallel from all points of the object perpendicular to the second plane of projection.

- Fig.7: An image is created thereby.

- Fig.8: The third plane of projection is added, perpendicular to the previous two.

- Fig.9: Projectors emanate parallel from all points of the object perpendicular to the third plane of projection.

- Fig.10: An image is created thereby.

- Fig.11: The fourth plane of projection is added parallel to the chosen inclined surface, and perforce, perpendicular to the first (frontal) plane of projection.

- Fig.12: Projectors emanate parallel from all points of the object perpendicularly from the inclined surface, and perforce, perpendicular to the fourth (auxiliary) plane of projection.

- Fig.13: An image is created thereby.

- Fig.14-16: The various planes of projection are unfolded to be planar with the Frontal plane of projection.

- Fig.17: The final appearance of an orthographic multiview projection and which includes an auxiliary view showing the true shape of an inclined surface

Territorial use

[edit]First-angle is used in most of the world.[5]

Third-angle projection is most commonly used in the United States[6] and Japan (in JIS B 0001:2010)[7] and is preferred in Australia, as laid down in AS 1100.101—1992 6.3.3.[8]

In the UK, BS8888 9.7.2.1 allows for three different conventions for arranging views: labelled views, third-angle projection, and first-angle projection.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

- ^ Ingrid Carlbom, Joseph Paciorek (1978), "Planar Geometric Projections and Viewing Transformations", ACM Computing Surveys, 10 (4): 465–502, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.532.4774, doi:10.1145/356744.356750, S2CID 708008

- ^ Ching, Frank (1985), Architectural Graphics - Second Edition, New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold, ISBN 978-0-442-21862-1

- ^ Bertoline, Gary R. Introduction to Graphics Communications for Engineers (4th Ed.). New York, NY. 2009

- ^ "Geometric Models - Jullien Models for Descriptive Geometry". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ "Third Angle Projection". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Madsen, David A.; Madsen, David P. (1 February 2016). Engineering Drawing and Design. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781305659728 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Third Angle Projection". Musashino Art University. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Full text of "AS 1100.101 1992 Technical Dwgs"". archive.org.

BS 308 (Part 1) Engineering Drawing Practice BS 8888 Technical product documentation and specification ISO 5456-2 Technical drawings – Projection methods – Part 2: Orthographic Representations (includes the truncated cone symbol)