Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interchange (road)

View on Wikipedia

32°55′27.2″N 96°45′50.0″W / 32.924222°N 96.763889°W

61°27′46″N 23°46′10″E / 61.46278°N 23.76944°E

In the field of road transport, an interchange (American English) or a grade-separated junction (British English) is a road junction that uses grade separations to allow for the movement of traffic between two or more roadways or highways, using a system of interconnecting roadways to permit traffic on at least one of the routes to pass through the junction without interruption from crossing traffic streams. It differs from a standard intersection, where roads cross at grade. Interchanges are almost always used when at least one road is a controlled-access highway (freeway) or a limited-access highway (expressway), though they are sometimes used at junctions between surface streets.

Terminology

[edit]Note: The descriptions of interchanges apply to countries where vehicles drive on the right side of the road. For left-side driving, the layout of junctions is mirrored. Both North American (NA) and British (UK) terminology is included.

- Freeway junction, highway interchange (NA), or motorway junction (UK)

- A type of road junction linking one controlled-access highway (freeway or motorway) facility to another, to other roads, or to a rest area or motorway service area. Junctions and interchanges are often (but not always) numbered either sequentially, or by distance from one terminus of the route (the "beginning" of the route).[1]

- The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) defines an interchange as "a system of interconnecting roadways in conjunction with one or more grade separations that provides for the movement of traffic between two or more roadways or highways on different levels."[2]

- System interchange

- A junction that connects multiple controlled-access highways.[3]

- Service interchange

- A junction that connects a controlled-access facility to a lower-order facility, such as an arterial or collector road.[3]

- The mainline is the controlled-access highway in a service interchange, while the crossroad is the lower-order facility that often includes at-grade intersections or roundabouts, which may pass over or under the mainline.[4]

- Complete interchange

- A junction where all possible movements between highways can be made from any direction.[5]

- Incomplete interchange

- A junction that is missing at least one movement between highways.[5]

- Ramp (NA), or slip road (UK/Ireland)

- A short section of road that allows vehicles to enter or exit a controlled-access highway.[6][7][8][9]

- Ingressing traffic is entering the highway via an on-ramp or entrance ramp, while egressing traffic is exiting the highway via an off-ramp or exit ramp.[10]

- Directional ramp

- A ramp that curves toward the desired direction of travel; i.e., a ramp that makes a left turn exits from the left side of the roadway (a left exit).[11]

- Semi-directional ramp

- A ramp that exits in a direction opposite from the desired direction of travel, then turns toward the desired direction. Most left turn movements are provided by a semi-directional ramp that exits to the right, rather than exiting from the left.[11]

- Weaving

- An undesirable situation where traffic entering and exiting a highway must cross paths within a limited distance.[12]

-

An interchange between the M0 and M4 motorways outside Budapest, showcases directional, semi-directional, and loop ramps.

47°24′18″N 19°18′55″E / 47.40500°N 19.31528°E -

The Light Horse Interchange in Sydney, the largest in Australia.[13]

33°47′53″S 150°51′15″E / 33.79806°S 150.85417°E

History

[edit]The concept of the controlled-access highway developed in the 1920s and 1930s in Italy, Germany, the United States, and Canada. Initially, these roads featured at-grade intersections along their length. Interchanges were developed to provide access between these new highways and heavily-travelled surface streets. The Bronx River Parkway and Long Island Motor Parkway were the first roads to feature grade-separations.[c][18][19] Maryland engineer Arthur Hale filed a patent for the design of a cloverleaf interchange on May 24, 1915,[20] though the conceptual roadwork was not realised until a cloverleaf opened on December 15, 1929, in Woodbridge, New Jersey, connecting New Jersey Route 25 and Route 4 (now U.S. Route 1/9 and New Jersey Route 35). It was designed by Philadelphia engineering firm Rudolph and Delano, based on a design seen in an Argentinian magazine.[21][22][19]

System interchange

[edit]

A system interchange connects multiple controlled-access highways, involving no at-grade signalised intersections.[3]

Four-legged interchanges

[edit]Cloverleaf interchange

[edit]

A cloverleaf interchange is a four-legged junction where left turns across opposing traffic are handled by non-directional loop ramps.[23] It is named for its appearance from above, which resembles a four-leaf clover.[21] A cloverleaf is the minimum interchange required for a four-legged system interchange. Although they were commonplace until the 1970s, most highway departments and ministries have sought to rebuild them into more efficient and safer designs.[23] The cloverleaf interchange was invented by Maryland engineer Arthur Hale, who filed a patent for its design on May 24, 1915.[20] The first one in North America opened on December 15, 1929, in Woodbridge, New Jersey, connecting New Jersey Route 25 and Route 4 (now U.S. Route 1/9 and New Jersey Route 35). It was designed by Philadelphia engineering firm Rudolph and Delano based on a design seen in an Argentinian magazine.[21][22]

The first cloverleaf in Canada opened in 1938 at the junction of Highway 10 and what would become the Queen Elizabeth Way.[24] The first cloverleaf outside of North America opened in Stockholm on October 15, 1935. Nicknamed Slussen, it was referred to as a "traffic carousel" and was considered a revolutionary design at the time of its construction.[25]

A cloverleaf offers uninterrupted connections between two roads but suffers from weaving issues. Along the mainline, a loop ramp introduces traffic prior to a second loop ramp providing access to the crossroad, between which ingress and egress traffic mixes. For this reason, the cloverleaf interchange has fallen out of favour in place of combination interchanges.[21] Some may be half cloverleaf containing ghost ramps which can be upgraded to full cloverleafs if the road is extended. US 70 and US 17 west of New Bern, North Carolina is an example.

Stack interchange

[edit]

A stack interchange is a four-way interchange whereby a semi-directional left turn and a directional right turn are both available. Usually, access to both turns is provided simultaneously by a single off-ramp. Assuming right-handed driving, to cross over incoming traffic and go left, vehicles first exit onto an off-ramp from the rightmost lane. After demerging from right-turning traffic, they complete their left turn by crossing both highways on a flyover ramp or underpass. The penultimate step is a merge with the right-turn on-ramp traffic from the opposite quadrant of the interchange. Finally, an on-ramp merges both streams of incoming traffic into the left-bound highway. As there is only one off-ramp and one on-ramp (in that respective order), stacks do not suffer from the problem of weaving, and due to the semi-directional flyover ramps and directional ramps, they are generally safe and efficient at handling high traffic volumes in all directions.

A standard stack interchange includes roads on four levels, also known as a four-level stack, including the two perpendicular highways, and one more additional level for each pair of left-turn ramps. These ramps can be stacked (cross) in various configurations above, below, or between the two interchanging highways. This makes them distinct from turbine interchanges, where pairs of left-turn ramps are separated but at the same level. There are some stacks that could be considered 5-level; however, these remain four-way interchanges, since the fifth level actually consists of dedicated ramps for HOV/bus lanes or frontage roads running through the interchange. The stack interchange between I-10 and I-405 in Los Angeles is a 3-level stack, since the semi-directional ramps are spaced out far enough, so they do not need to cross each other at a single point as in a conventional four-level stack.

Stacks are significantly more expensive than other four-way interchanges are due to the design of the four levels; additionally, they may suffer from objections of local residents because of their height and high visual impact. Large stacks with multiple levels may have a complex appearance and are often colloquially described as Mixing Bowls, Mixmasters (for a Sunbeam Products brand of electric kitchen mixers), or as Spaghetti Bowls or Spaghetti Junctions (being compared to boiled spaghetti). However, they consume a significantly smaller area of land compared to a cloverleaf interchange.

Combination interchange

[edit]

A combination interchange (sometimes referred to by the portmanteau cloverstack)[26][27] is a hybrid of other interchange designs. It uses loop ramps to serve slower or less-occupied traffic flow, and flyover ramps to serve faster and heavier traffic flows.[28][29] If local and express ways serving the same directions and each roadway is connected righthand to the interchange, extra ramps are installed. The combination interchange design is commonly used to upgrade cloverleaf interchanges to increase their capacity and eliminate weaving.[30]

Turbine interchange

[edit]- Lummen, Belgium,[31] 50°59′58″N 5°13′25″E / 50.9994°N 5.2236°E

- Jacksonville, Florida, US,[32] 30°15′11″N 81°30′59″W / 30.2531°N 81.5163°W

- Charlotte, North Carolina, US,[33] 35°20′54″N 80°44′01″W / 35.3482°N 80.7335°W

- Amarillo, Texas, US,[34] 35°11′34″N 101°50′14″W / 35.1929°N 101.8371°W

Some turbine-stack hybrids:

The turbine interchange is an alternative four-way directional interchange. The turbine interchange requires fewer levels (usually two or three) while retaining directional ramps throughout. It features right-exit, left-turning ramps that sweep around the center of the interchange in a clockwise spiral. A full turbine interchange features a minimum of 18 overpasses, and requires more land to construct than a four-level stack interchange; however, the bridges are generally short in length. Coupled with reduced maintenance costs, a turbine interchange is a lower cost alternative to a stack.[35]

50°53′30.1″N 4°27′15.3″E / 50.891694°N 4.454250°E

Windmill interchange

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2022) |

NL-ZH 51°51′55″N 4°30′55″E / 51.8654°N 4.5154°E

A windmill interchange is similar to a turbine interchange, but it has much sharper turns, reducing its size and capacity. The interchange is named for its similar overhead appearance to the blades of a windmill.

A variation of the windmill, called the diverging windmill, increases capacity by altering the direction of traffic flow of the interchanging highways, making the connecting ramps much more direct.[36] There also is a hybrid interchange somewhat like the diverging windmill in which left turn exits merge on the left, but it differs in that the left turn exits use left directional ramps.

Braided interchange

[edit]

A braided or diverging interchange is a two-level, four-way interchange. An interchange is braided when at least one of the roadways reverses sides. It seeks to make left and right turns equally easy.[37] In a pure braided interchange, each roadway has one right exit, one left exit, one right on-ramp, and one left on-ramp, and both roadways are flipped.

The first pure braided interchange was built in Baltimore at Interstate 95 at Interstate 695;[38] however, the interchange was reconfigured in 2008 to a traditional stack interchange.[39]

- Examples

- Interstate 65 and Interstate 20/Interstate 59 in Birmingham, Alabama (33°31′17″N 86°49′35″W / 33.521414°N 86.826513°W)

- Interstate 196 and U.S. Route 131 in Grand Rapids, Michigan (42°58′21″N 85°40′40″W / 42.972487°N 85.677781°W)

- Interstate 77 and Interstate 85 in Charlotte, North Carolina (35°16′23″N 80°50′44″W / 35.272967°N 80.845550°W)

- Eastern Ring Road and Southern Ring Branch Road, Riyadh (24°37′54″N 46°48′12″E / 24.631542°N 46.803334°E)

Three-level roundabout

[edit]50°33′23″N 7°14′55″E / 50.556257°N 7.248577°E

52°23′04″N 4°42′27″E / 52.384416°N 4.707492°E

A three-level roundabout interchange features a grade-separated roundabout which handles traffic exchanging between highways.[9] The ramps of the interchanging highways meet at a roundabout, or rotary, on a separated level above, below, or in the middle of the two highways.

Three-legged interchanges

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (July 2021) |

These interchanges can also be used to make a "linking road" to the destination for a service interchange, or the creation of a new basic road as a service interchange.

Trumpet interchange

[edit]

45°24′41″N 75°44′7″W / 45.41139°N 75.73528°W

Trumpet interchanges may be used where one highway terminates at another highway, and are named as such for to their resemblance to trumpets. They are sometimes called jug handles.[40]

These interchanges are very common on toll roads, as they concentrate all entering and exiting traffic into a single stretch of roadway, where toll plazas can be installed once to handle all traffic, especially on ticket-based tollways. A double-trumpet interchange can be found where a toll road meets another toll road or a free highway. They are also useful when most traffic on the terminating highway is going in the same direction. The turn that is used less often would contain the slower loop ramp.[41]

Trumpet interchanges are often used instead of directional or semi-directional T or Y interchanges because they require less bridge construction but still eliminate weaving.[citation needed]

T and Y interchanges

[edit]A full Y interchange (also known as a directional T interchange) is typically used when a three-way interchange is required for two or three highways interchanging in semi-parallel/perpendicular directions, but it can also be used in right-angle cases as well. Their connecting ramps can spur from either the right or left side of the highway, depending on the direction of travel and the angle.

Directional T interchanges use flyover/underpass ramps for both connecting and mainline segments, and they require a moderate amount of land and moderate costs since only two levels of roadway are typically used. Their name derives from their resemblance to the capital letter T, depending upon the angle from which the interchange is seen and the alignment of the roads that are interchanging. It is sometimes known as the "New England Y", as this design is often seen in the northeastern United States, particularly in Connecticut.[42]

This type of interchange features directional ramps (no loops, or weaving right to turn left) and can use multilane ramps in comparatively little space. Some designs have two ramps and the "inside" through road (on the same side as the freeway that ends) crossing each other at a three-level bridge. The directional T interchange is preferred to a trumpet interchange because a trumpet requires a loop ramp by which speeds can be reduced, but flyover ramps can handle much faster speeds. The disadvantage of the directional T is that traffic from the terminating road enters and leaves on the passing lane, so the semi-directional T interchange (see below) is preferred.

The interchange of Highway 416 and Highway 417 in Ontario, constructed in the early 1990s, is one of the few directional T interchanges, as most transportation departments had switched to the semi-directional T design.

As with a directional T interchange, a semi-directional T interchange uses flyover (overpass) or underpass ramps in all directions at a three-way interchange. However, in a semi-directional T, some of the splits and merges are switched to avoid ramps to and from the passing lane, eliminating the major disadvantage of the directional T. Semi-directional T interchanges are generally safe and efficient, though they do require more land and are costlier than trumpet interchanges.

Semi-directional T interchanges are built as two- or three-level junctions, with three-level interchanges typically used in urban or suburban areas where land is more expensive. In a three-level semi-directional T, the two semi-directional ramps from the terminating highway cross the surviving highway at or near a single point, which requires both an overpass and underpass. In a two-level semi-directional T, the two semi-directional ramps from the terminating highway cross each other at a different point than the surviving highway, necessitating longer ramps and often one ramp having two overpasses. Highway 412 has a three-level semi-directional T at Highway 407 and a two-level semi-directional T at Highway 401.

-

Full Y interchange

-

Complex T interchange of SR 85 and SR 87 in San Jose, California. 37°15′21″N 121°51′32″W / 37.255721°N 121.858878°W

-

Semi-directional T interchange

-

Two level semi-directional T interchange in Orbe, Switzerland. 46°43′42″N 6°34′11″E / 46.72836°N 6.569738°E

Service interchange

[edit]Service interchanges are used between a controlled-access route and a crossroad that is not controlled-access. A full cloverleaf may be used as a system or a service interchange.[23]

Diamond interchange

[edit]

28°32′56.3″N 81°27′25.9″W / 28.548972°N 81.457194°W

A diamond interchange is an interchange involving four ramps where they enter and leave the freeway at a small angle and meet the non-freeway at almost right angles. These ramps at the non-freeway can be controlled through stop signs, traffic signals, or turn ramps.

Diamond interchanges are much more economical in use of materials and land than other interchange designs, as the junction does not normally require more than one bridge to be constructed. However, their capacity is lower than other interchanges and when traffic volumes are high they can easily become congested.

- Double roundabout diamond

43°53′3″N 78°43′20″W / 43.88417°N 78.72222°W

A double roundabout diamond interchange, also known as a dumbbell interchange or a dogbone interchange, is similar to the diamond interchange, but uses a pair of roundabouts in place of intersections to join the highway ramps with the crossroad. This typically increases the efficiency of the interchange when compared to a diamond, but is only ideal in light traffic conditions. In the dogbone variation, the roundabouts do not form a complete circle, instead having a teardrop shape, with the points facing towards the center of the interchange. Longer ramps are often required due to line-of-sight requirements at roundabouts.[43]

Partial cloverleaf interchange

[edit]A partial cloverleaf interchange (often shortened to the portmanteau, parclo) is an interchange with loops ramps in one to three quadrants, and diamond interchange ramps in any number of quadrants. The various configurations are generally a safer modification of the cloverleaf design, due to a partial or complete reduction in weaving, but may require traffic lights on the lesser-travelled crossroad. Depending on the number of ramps used, they take up a moderate to large amount of land, and have varying capacity and efficiency.[44]

Parclo configurations are given names based on the location of and number of quadrants with ramps. The letter A denotes that, for traffic on the controlled-access highway, the loop ramps are located in advance of (or approaching) the crossroad, and thus provide an onramp to the highway. The letter B indicated that the loop ramps are beyond the crossroad, and thus provide an offramp from the highway. These letters can be used together when opposite directions of travel on the controlled-access highway are not symmetrical, thus a parclo AB features a loop ramp approaching the crossroad in one direction, and beyond the crossroad in the opposing direction, as in the example image.[45]

-

A parclo A4 interchange along Highway 407 on the Mississauga / Milton, Ontario, boundary

43°34′17.8″N 79°47′23.6″W / 43.571611°N 79.789889°W -

A parclo AB2, or folded-diamond interchange along Bundesautobahn 7 in Germany

47°38′28.68″N 10°31′40.08″E / 47.6413000°N 10.5278000°E

Diverging diamond interchange

[edit]

33°39′23.5″N 84°29′51.5″W / 33.656528°N 84.497639°W

A diverging diamond interchange (DDI) or double crossover diamond interchange (DCD) is similar to a traditional diamond interchange, except the opposing lanes on the crossroad cross each other twice, once on each side of the highway. This allows all highway entrances and exits to avoid crossing the opposite direction of travel and saves one signal phase of traffic lights each.[46]

The first DDIs were constructed in the French communities of Versailles (A13 at D182), Le Perreux-sur-Marne (A4 at N486) and Seclin (A1 at D549), in the 1970s.[47] Despite the fact that such interchanges already existed, the idea for the DDI was "reinvented" around 2000, inspired by the freeway-to-freeway interchange between Interstate 95 and I-695 north of Baltimore.[48] The first DDI in the United States opened on July 7, 2009, in Springfield, Missouri, at the junction of Interstate 44 and Missouri Route 13.[49][50]

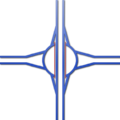

Single-point urban interchange

[edit]

43°35′36.5″N 116°23′37.4″W / 43.593472°N 116.393722°W

A single-point urban interchange (SPUI) or single-point diamond interchange (SPDI) is a modification of a diamond interchange in which all four ramps to and from a controlled-access highway converge at a single, three-phase traffic light in the middle of an overpass or underpass. While the compact design is safer, more efficient, and offers increased capacity—with three light phases as opposed to four in a traditional diamond, and two left turn queues on the arterial road instead of four—the significantly wider overpass or underpass structure makes them more costly than most service interchanges.[51][52]

Single-point interchanges were first built in the early 1970s along U.S. Route 19 in the Tampa Bay area of Florida, including the SR 694 interchange in St. Petersburg and SR 60 in Clearwater.[53]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Interstate System". Federal Highway Administration. February 5, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design 2000 (2001). "10.1 – Introduction and General Types of Interchanges". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF) (4th ed.). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 10.1-1. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hotchkin, Scott (20 March 2017). "The Amazing World of: Interchange Designs". Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design 2000 (2001). "10.8.2 – Types of Separation Structures". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF) (4th ed.). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 10-14. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Epps, James W.; Stafford, Donald B. (1974). "Interchange Development Patterns on Interstate Highways in South Carolina" (PDF). 53rd Annual Meeting of Highway Research Board, Washington, DC. No. 508. Transportation Research Record. ISSN 0361-1981. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Torbic, Darren J.; Lucas, Lindsay M.; Harwood, Douglas W.; et al. (2017). Design of Interchange Loop Ramps and Pavement/Shoulder Cross-Slope Breaks. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 1.1 Background. p. 18. doi:10.17226/24683. ISBN 978-0-309-45554-1.

- ^ "Motorways (253 to 273) – Joining the motorway (259)". The Highway Code. Government of the United Kingdom. June 27, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ "Motorways (253 to 273) – Leaving the motorway (272 to 273)". The Highway Code. Government of the United Kingdom. June 27, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b The Design of Major Interchanges (PDF) (Report). Transport Infrastructure Ireland. December 2020. p. 6-1. DN-GEO-03041. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "Ingress/Egress". Texas Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Iowa Department of Transportation (September 1, 1995). "Cross Sections of One-Way Ramps and Loops" (PDF). Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board (2011). "4.2.3 Weaving Segments". Guidelines for Ramp and Interchange Spacing (PDF) (Report). National Academy of Sciences. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-309-15548-9. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Light Horse Interchange – Westlink M7/M4 Motorway Interchange" (PDF). Westlink Motorway Limited. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "Bronx River Parkway". www.dot.ny.gov. New York Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "City Opens Bronx Park Way to Traffic". The New York Times. September 17, 1922. p. 14. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Adcock, Sylvia (April 12, 1998). "The Age of the Auto: Sportsman William K. Vanderbilt II's cup race paves the way to the future". Newsday. p. A16. Archived from the original on January 31, 2005.

- ^ "35 cars to race on the Motor Parkway" (PDF). The New York Times. October 10, 1908. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Built to Meander, Parkway Fights to Keep Measured Pace". New York Times. June 6, 1995. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Leisch, Joel P.; Morrall, John (2014). Evolution of Interchange Design in North America (PDF) (Report). Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "US Patent No. 1173505A". Google Patents. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Hugo (April 7, 2004). "A Major Lane Change". LA Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "New Bridge Over Raritan, 'Express Route' Opens Today". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. December 15, 1929. p. 23. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zhong, Hantao (2012). Free-flow Parclo Interchange vs. the Cloverleaf Interchange with C-D Roads and the All-Directional Four-level Interchange: A Comparison of Geometrics, Construction Cost, and Right of Way Requirements (PDF) (Thesis). Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina State University. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Shragge, John; Bagnato, Sharon (1984). From Footpaths to Freeways. Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications, Historical Committee. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-7743-9388-2.

- ^ Rundquist, Solveig (June 17, 2014). "The octopus that could save Slussen". Sweden: The Local. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Bureau of Environment Conference Report: NHDOT Monthly Natural Resource Agency Coordination Meeting" (PDF). New Hampshire Department of Transportation. August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ McDaniel, Dana L. (February 5, 2015). "Ordinance No. 12-15" (PDF). City of Dublin, Ohio. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design 2000 (2001). "10 – Grade Separations and Interchanges". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF) (4th ed.). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. pp. 803–805. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Publication 13M – Design Manual, Part 2 Highway Design, Chapter 4 (PDF) (6 ed.). Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. April 2021. p. 4-4. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design 2000 (2001). "10 – Grade Separations and Interchanges". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF) (4th ed.). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 10-72 – 10-76. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Turbine Interchange Analysis in Lummen". Jan De Nul Group. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "I-94 East Metro Interchange Study". Minnesota Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via ArcGIS.

- ^ "I-485/I-85 Turbine Interchange Design-Build". STV Inc. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Andrew, Peter (July 22, 2015). "The art of the interchange". Politico. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Parsons, Jim (May 23, 2012). "Rare 'Turbine' Design for Charlotte's I-85/485 Interchange". ENR Southeast. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "I-40 AT I-440/ US 1/ US 64 Interchange Feasibility Study, Prepared for: North Carolina Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization" (PDF). Parsons Brinckerhoff. August 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Dror Bar-Natan's Image Gallery: Knotted Objects: Baltimore Interchange". www.math.toronto.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Manaugh, Geoff (2005-12-29). "The knot driver". Archived from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ Lookingbill, Amy P. (3 July 2007). "Construction still rolling along I-95 to prepare for Express Toll Lanes". The Avenue News. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ "48" (PDF). 2013 Design Manual (Report). Indiana Department of Transportation. 2013. p. 69. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design 2000 (2001). "10 – Grade Separations and Interchanges". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF) (4th ed.). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 10-32. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Milano, Lou (4 March 2022). "CT Has an Absurd Number of Left Exits, the Most in New England by far". I95 Rock.

- ^ "10.2.7 Double Roundabout Diamond". South Carolina Roadway Design Manual (PDF) (Report). South Carolina Department of Transportation. February 2021. pp. 10.2-7–10.2-8. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Task Force on Geometric Design (2000). "10.9.3.6.1 – Partial Cloverleaf Ramp Arrangements". A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (PDF). AASHTO. pp. 10-60–10-63. ISBN 1-56051-156-7. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "10.2.10 Partial Cloverleafs". South Carolina Roadway Design Manual (PDF) (Report). South Carolina Department of Transportation. February 2021. pp. 10.2-11–10.2-12. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Warren; Jagannathan, Ram (October 2009). "Double Crossover Diamond Interchange". Federal Highway Administration. FHWA-HRT-09-054. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Staff (June 13, 2013). "I-64 Interchange at Route 15, Zion Crossroads". Virginia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Chlewicki, Gilbert (2003). "New Interchange and Intersection Designs: The Synchronized Split-Phasing Intersection and the Diverging Diamond Interchange" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ "Missouri Department of Transportation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Staff (June 2011). "I-44/Route 13 Interchange Reconstruction: Diverging Diamond Design". Missouri Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "Innovative Intersections and Interchanges". Virginia Department of Transportation. November 17, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ "Single-Point Urban Interchanges". Missouri Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Bonneson, James A.; Messer, Carroll J. (March 1989). National Survey of Single-Point Urban Interchanges (PDF) (Report). Federal Highway Administration. FHWA/TX-88/1148-1. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Glossary – Part of the publication Highway Design Handbook for Older Drivers and Pedestrians by the Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center branch of the U.S. Federal Highway Administration

- Kurumi.com U.S. interchanges directory

- Detailed history of interchanges with diagrams (in German)

- How New Jersey Saved Civilization: The first cloverleaf interchange

![The Light Horse Interchange in Sydney, the largest in Australia.[13] 33°47′53″S 150°51′15″E / 33.79806°S 150.85417°E / -33.79806; 150.85417](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Light_Horse_Interchange_%28aerial_view%29.jpg/120px-Light_Horse_Interchange_%28aerial_view%29.jpg)