Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

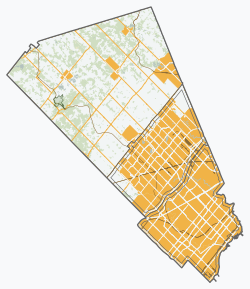

Mississauga

View on Wikipedia

Mississauga[a] is a Canadian city in the province of Ontario. Situated on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario in the Regional Municipality of Peel, it borders Toronto (Etobicoke) to the east, Brampton to the north, Milton to the northwest, and Oakville to the southwest. With a population of 717,961 as of 2021, Mississauga is the seventh-most populous municipality in Canada, third-most in Ontario, and second-most in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) after Toronto itself.[3][4] However, for the first time in its history, the city's population declined according to the 2021 census, from a 2016 population of 721,599 to 717,961, a 0.5 per cent decrease.[1]

Key Information

The growth of Mississauga was initially attributed to its proximity to Toronto.[5] However, during the latter half of the 20th century, the city attracted a diverse and multicultural population. Over time, it built up a thriving, transit-oriented central business district of its own; the Mississauga City Centre.[6][7] Malton, a neighbourhood of the city located in its northeast end, is home to Toronto Pearson International Airport, Canada's busiest airport, as well as the headquarters of many Canadian and multinational corporations. Mississauga is not a traditional city, but is instead an amalgamation of three former villages, two townships, and a number of rural hamlets (a general pattern common to several suburban GTA cities) that were significant population centres, with none being clearly dominant, prior to the city's incorporation that later coalesced into a single urban area.[8]

Indigenous people have lived in the area for thousands of years and Mississauga is situated on the traditional territory of the Wendat, Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg people, including the namesake Mississaugas.[9] Most of present-day Mississauga was founded in 1805 as Toronto Township[10] within York County, and became part of Peel County when new counties were formed by splitting off parts of the original county in 1851. Mississauga itself was established in 1968 as a town, and was reincorporated as a city in 1974, when Peel was restructured into a regional municipality.[11]

Etymology

[edit]The name Mississauga comes from the Anishinaabe word Misi-zaagiing, meaning '[those at the] Great River-mouth'.

Other forms such as Sauga and, in reference to the city's residents, Saugans,[12] and Mississaugans,[2] are also commonly used.

History

[edit]Palaeo-Indigenous period (9000–8500 BCE)

[edit]A single site in Mississauga with Hi-Lo projectile points[13] was registered in the Ontario Ministry of Culture database of archaeological sites.[14] Lake Ontario was much smaller at this time, and sites from this period may be 500 m into the lake.[14]

Archaic period (8000–1000 BCE)

[edit]According to Smith,[14] there was a growing population at this time. There are 23 known Archaic sites in Mississauga, mostly in the Credit River and Cooksville Creek drainage systems. People would congregate at rapids and the mouths of these rivers to catch fish during spawning runs. They would harvest nuts and wild rice at the wetland margins in the late summer. During late Archaic times, there were large cemeteries.[14]

Woodland period (1000 BCE – 1650 CE)

[edit]"The accelerating upward population increase continued,"[14]: 62 with 23 known sites from this period. Pottery first appears during this period in the style of the Point Peninsula complex, and near the end of the Woodland period, the first semi-permanent villages appear. Artifacts show that these people engaged in long-distance trade, likely as part of the Hopewell tradition.[14]

In the late Woodland period (500–1650 CE), "the band level of social organization that characterized earlier cultures gave way eventually to the tribal level of the Ontario Iroquoian Tradition,"[14]: 67 and people began cultivation of crops such as maize, beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco. This led to the development of the Wyandot or Huron, Iroquoian-speaking culture. The Lightfoot site with four to six longhouses was located on the Credit River near Mississauga's border with Brampton. Another village with many longhouses was on the Antrex site, located on a wide ridge bounded by two small tributaries of Cooksville Creek.[14]

Arrival of the Haudenosaunee, the Anishinaabe, and the Europeans

[edit]Around the end of the Woodland period, the Haudenosaunee, another Iroquoian confederacy, began to move into the area, and, as part of a long conflict known as the Beaver wars, they had dispersed the Wyandot by 1650.[15][16] But by 1687, the Haudenosaunee had abandoned their new settlements along the north shore of Lake Ontario.[17]: 65

The Algonquian-speaking Anishinaabe Ojibwe people had been aligned with the Wyandot, and when they were dispersed, the Anishinaabe expanded eastward into the Credit River Valley area, clashing with the Haudenosaunee and eventually taking over when the Haudenosaunee retreated.[17] The European traders would gather annually at the mouth of what is now known as the Credit River to give the Anishinaabe credit for the following year. "From this, the Mississauga bands at the western end of the lake became known collectively as the Credit River Mississaugas."[15]: 108

Toronto Township, consisting of most of present-day Mississauga, was formed on 2 August 1805 [citation needed] when officials from York (what is now the City of Toronto) purchased 85,000 acres (340 km2) of land from the Mississaugas under Treaty 14.[9] A second treaty was signed in 1818 that surrendered 2,622 km2 of Mississauga land to the British Crown. In total Mississauga is covered by four treaties: Treaty 14, Treaty 19, Treaty 22 and Treaty 23.[9]

Founding of Settlements

[edit]Mississauga's original villages (and some later incorporated towns) settled included Clarkson, Cooksville, Dixie, Erindale (called Springfield until 1890), Lakeview, Lorne Park, Port Credit, Sheridan, and Summerville. The region became known as Toronto Township. Part of northeast Mississauga, including the Airport lands and Malton were a part of Toronto Gore Township.[18]

After the land was surveyed, the Crown gave much of it in the form of land grants to United Empire Loyalists who emigrated from the Thirteen Colonies during and after the American Revolution, as well as loyalists from New Brunswick. A group of settlers from New York State arrived in the 1830s. The government wanted to compensate the Loyalists for property lost in the colonies and encourage development of what was considered frontier. In 1820, the government purchased additional land from the Mississaugas. Additional settlements were established, including: Barbertown, Britannia, Burnhamthorpe, Churchville, Derry West, Elmbank, Malton, Meadowvale (Village), Mount Charles, and Streetsville. European-Canadian settlement led to the eventual displacement of the Mississaugas. In 1847, the government relocated them to a reserve in the Grand River Valley, near present-day Hagersville.[19][20] Pre-confederation, the Township of Toronto was formed as a local government; settlements within were not legal villages until much later.[21][22]

Suburban growth and the creation of Mississauga

[edit]Except for small villages and some gristmills and brickworks served by railway lines, most of present-day Mississauga was agricultural land, including fruit orchards, through much of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. In the 1920s, cottages were constructed along the shores of Lake Ontario as weekend getaway homes for Torontonians.[21]

The Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW) highway, one of the first controlled-access highways in the world, opened from Highway 27 to Highway 10 (Hurontario Street) in Port Credit, in 1935 and later expanded to Hamilton and Niagara in 1939.

In 1937, 1,410.8 acres of land was sold to build Malton Airport (which later became Pearson Airport). It became Canada's busiest airport which later put the end to the community of Elmbank.[23]

The first prototypical suburban growth of Toronto Township began after World War II,[24] Applewood Acres was the first major planned development near the QEW and Dixie Road,[25] and urbanization soon rapidly expanded north and west. In 1952, Toronto Township annexed the southern portion of Toronto Gore Township.[26] Two large new towns; Erin Mills and (New) Meadowvale, were started in 1968 and 1969, respectively. Most of Mississauga was built out by 2005.[27]

While the Township had many settlements within it, none of them (save for the larger enclave communities of Port Credit and Streetsville) were incorporated, and all residents were represented by a singular Township council (Malton had special status as a police village, allowing it partial autonomy). To reflect the community's shift away from rural to urban, council desired conversion into a town, and in 1965 a call for public input on naming it received thousands of letters offering hundreds of different suggestions.[28] "Mississauga" was chosen by plebiscite over "Sheridan" by a vote of 11,796 to 4,331,[29] and in 1968 the reincorporation went forward, absorbing Malton in the process. Port Credit and Streetsville remained separate, uninterested in ceding their autonomy or being taxed to the needs of a growing municipality. Political will, as well as a belief that a larger city would be a hegemony in Peel County, kept them as independent enclaves within the Town of Mississauga, but both were amalgamated into Mississauga when it reincorporated as a city in 1974. At this time, Mississauga annexed lands west of Winston Churchill Boulevard from Oakville in the northwest,[b][30] in exchange for lands in the northernmost extremity (which included Churchville) south of Steeles Avenue which were transferred to Brampton.[31] That year, Square One Shopping Centre opened; it has since expanded several times.[32]

On 10 November 1979, a 106-car freight train derailed on the CP rail line while carrying explosive and poisonous chemicals just north of the intersection of Mavis Road and Dundas Street. One of the tank cars carrying propane exploded, and since other tank cars were carrying chlorine, the decision was made to evacuate nearby residents. With the possibility of a deadly cloud of chlorine gas spreading through Mississauga, 218,000 people were evacuated.[33] Residents were allowed to return home once the site was deemed safe. At the time, it was the largest peacetime evacuation in North American history. Due to the speed and efficiency with which it was conducted, many cities later studied and modelled their own emergency plans after Mississauga's. For many years afterwards, the name "Mississauga" was, for Canadians, associated with a major rail disaster.[34]

North American telephone customers placing calls to Mississauga (and other post-1970 Ontario cities) may not recognise the charge details on their bills. The area's incumbent local exchange carrier, Bell Canada, continues to split the city into five historical rate centres–Clarkson, Cooksville, Malton, Port Credit, and Streetsville. However, they are combined as a single Mississauga listing in the phone book. The first Touch-Tone telephones in Canada were introduced in Malton on 15 June 1964.[35]

On 1 January 2010, Mississauga bought land from the Town of Milton and expanded its border by 400 acres (1.6 km2), to Highway 407, affecting 25 residents.[36] Also in January 2010, the Mississaugas and the federal government settled a land claim, in which the band of indigenous people received $145,000,000, as just compensation for their land and lost income.[37]

Geography

[edit]

Mississauga covers 288.42 square kilometres (111.36 sq mi) of land,[38] fronting 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) of shoreline on Lake Ontario.

Mississauga is bounded by Oakville and Milton to the west/southwest, Brampton to the north, Toronto to the east, and Lake Ontario to the south/south-east. Halton Hills borders Mississauga's north-west corner. With the exception of the southeast border with Toronto (Etobicoke Creek), Mississauga shares a land border with all previously mentioned municipalities.

Two major river valleys feed into the lake. The Credit River is by far the longest with the heaviest flow, it divides the western side of Mississauga from the central/eastern portions and enters the lake at the Port Credit harbour. The indented, mostly forested valley was inhabited by first nation peoples long before European exploration of the area. The valley is protected and maintained by the Credit Valley Conservation Authority (CVCA).[39]

Etobicoke Creek forms part of the eastern border of Mississauga with the city of Toronto. North of there it passes through the western limits of Pearson Airport. There have been two aviation accidents, in 1978 and 2005 where aircraft overshot the runway and slid into the Etobicoke creek banks. In 1954, heavy flooding resulted in some homes along the riverbank being swept into the lake after heavy rains from Hurricane Hazel. Since that storm, houses are no longer constructed along the floodplain. The creek and its tributaries are administered by the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA).[40]

Most land in Mississauga drains to either of the two main river systems, with the exception of the smaller Mary Fix and Cooksville Creeks which run roughly through the centre of Mississauga entering the lake near Port Credit. Some small streams and reservoirs are part of the Sixteen Mile Creek system in the far north-west corner of the city, but these drain toward the lake in neighbouring Milton and Oakville.

The shoreline of former Glacial Lake Iroquois roughly follows the Dundas Street alignment, although it is not noticeable in some places but is more prominent in others, such as the site of the former brickyard (Shoreline Dr. near Mavis Rd.), the ancient shoreline promenteau affords a clear view of downtown Toronto and Lake Ontario on clear days. The land in Mississauga in ranges from a maximum elevation of 214 m (699 ft) ASL in the far western corner, near the Hwy. 407/401 junction, to a minimum elevation at the Lake Ontario shore of 76 m (249 ft) above sea level.

Apart from the embankments of Credit River valley, it tributaries and the Iroquois shoreline, the only noticeable hills in Mississauga are actually part of the former Britannia Landfill, now a golf course on Terry Fox Way.

On August 17, 2024, heavy rainfalls caused localized flooding in areas across the city. The floods caused many traffic disruptions as well as dangerous road conditions and road closures. All creeks and rivers throughout Mississauga were either at full capacity or flooded into parks and greenspaces.[41]

Neighbourhoods/areas

[edit]

There are 25 neighbourhoods in Mississauga:[42]

- Applewood

- Central Erin Mills

- Churchill Meadows

- Clarkson

- Cooksville

- Creditview

- Dixie

- East Credit

- Erin Mills

- Erindale

- Fairview

- Hurontario

- Lakeview

- Lisgar

- Lorne Park

- Malton

- Meadowvale

- Meadowvale Village

- Mineola

- Mississauga Valleys

- Port Credit

- Rathwood

- Rockwood Village

- Sheridan

- Streetsville

Climate

[edit]Mississauga's climate is similar to that of Toronto and is considered to be moderate,[43] located in plant hardiness zone 7a.[44] Under the Köppen climate classification, Mississauga has a humid continental climate (Dfa/Dfb).[45] Summers can bring periods of high temperatures accompanied with high humidity.[43] While the average daily high temperature in July and August is 27 °C (80.6 °F), temperatures can rise above 32 °C (89.6 °F). In an average summer, there are an average of 15.8 days where the temperature rises above 30 °C (86.0 °F).[46] Winters can be cold with temperatures that are frequently below freezing.[43] In January and February, the mean temperatures are −5.5 °C (22.1 °F) and −4.5 °C (23.9 °F) respectively, it is common for temperatures to fall to −15 °C (5.0 °F), usually for only short periods.[43] In an average winter, there are 3.9 nights where the temperature falls below −20 °C (−4.0 °F).[46][43] The amount of snowfall received during an average winter season is 108.5 centimetres (42.7 in), averaging 44.4 days with measurable snowfall.[46] The climate of Mississauga is officially represented by Pearson International Airport but because of its topography and large surface area conditions can differ depending on location: fog tends to be more common along the Lakeshore and in the Credit River Valley at certain times of year, particularly during the spring and autumn.[citation needed]

During snowfalls when temperatures hover close to freezing, northern parts of the city, such as around Derry Road, including Pearson Airport away from warmer Lake Ontario usually get more snow that sticks to the ground because of the lower temperatures, often when rain transitions into snow or mixed precipitation.[citation needed] The reverse occurs when a strong storm approaches from the south kicking up lake effect snow, bringing higher snowfall totals to south Mississauga. The city usually experiences at least six months of snow-free weather; however, there is the odd occurrence where snow does fall either in October or May, none which sticks to the ground.[citation needed] The Port Credit and Lakeview areas have a micro-climate more affected by the proximity of the open lake, warming winter temperatures as a result, but it can be sharply cooler on spring and summer afternoons, this can also be the case in Clarkson, but with much less consistency.[citation needed]

Most thunderstorms are not severe but can occasionally bring violent winds. The last known tornado to cause significant damage touched down on 7 July 1985, when an F1-rated tornado struck an industrial park in the Meadowvale area (Argentia Road), heavily damaging some buildings and some parked tractor trailers. A relatively strong tornado tore a path across Mississauga (then part of Toronto Township) on 24 June 1923, cutting a swath from present-day Meadowvale to near Cooksville, killing four people and causing massive property damage in a time when most of Mississauga was still rural farmland dotted with fruit orchards.[47][48][49]

| Climate data for Lester B. Pearson International Airport (Brampton and North Mississauga) WMO ID: 71624; coordinates 43°40′38″N 79°37′50″W / 43.67722°N 79.63056°W, elevation: 173.4 m (569 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1937–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 19.0 | 18.3 | 29.6 | 37.9 | 42.6 | 45.6 | 50.3 | 46.6 | 48.0 | 39.1 | 28.6 | 23.9 | 50.3 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.3 (100.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5 (23) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −8.9 (16.0) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−5 (23) |

3.9 (39.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.3 (−24.3) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−31.3 (−24.3) |

| Record low wind chill | −44.7 | −38.9 | −36.2 | −25.4 | −9.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −8.0 | −13.5 | −25.4 | −38.5 | −44.7 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.6 (2.43) |

50.2 (1.98) |

50.5 (1.99) |

76.7 (3.02) |

77.6 (3.06) |

80.7 (3.18) |

74.0 (2.91) |

68.5 (2.70) |

69.4 (2.73) |

67.2 (2.65) |

71.8 (2.83) |

58.6 (2.31) |

806.8 (31.76) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 33.8 (1.33) |

23.9 (0.94) |

34.0 (1.34) |

70.7 (2.78) |

77.5 (3.05) |

80.7 (3.18) |

74.0 (2.91) |

68.5 (2.70) |

69.4 (2.73) |

67.0 (2.64) |

62.7 (2.47) |

35.3 (1.39) |

697.4 (27.46) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 31.5 (12.4) |

27.7 (10.9) |

17.2 (6.8) |

4.5 (1.8) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.1) |

9.3 (3.7) |

24.1 (9.5) |

114.5 (45.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.2 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 14.9 | 147.3 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.2 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 10.4 | 7.5 | 114.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 12.7 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.24 | 3.6 | 9.2 | 44.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 15:00) | 69.7 | 65.7 | 58.5 | 53.4 | 53.6 | 54.4 | 52.9 | 55.2 | 57.3 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 70.5 | 60.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 79.7 | 112.2 | 159.4 | 204.4 | 228.2 | 249.7 | 294.4 | 274.5 | 215.7 | 163.7 | 94.2 | 86.2 | 2,161.4 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 27.6 | 38.0 | 43.2 | 50.8 | 50.1 | 54.1 | 63.0 | 63.4 | 57.4 | 47.8 | 32.0 | 30.9 | 46.5 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[50][51][52] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 172,352 | — |

| 1976 | 250,017 | +45.1% |

| 1981 | 315,055 | +26.0% |

| 1986 | 374,005 | +18.7% |

| 1991 | 463,388 | +23.9% |

| 1996 | 544,382 | +17.5% |

| 2001 | 612,925 | +12.6% |

| 2006 | 668,549 | +9.1% |

| 2011 | 713,443 | +6.7% |

| 2016 | 721,599 | +1.1% |

| 2021 | 717,961 | −0.5% |

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Mississauga had a population of 717,961 living in 244,575 of its 254,089 total private dwellings, a change of -0.5% from its 2016 population of 721,599. With a land area of 292.74 km2 (113.03 sq mi), it had a population density of 2,452.6/km2 (6,352.1/sq mi) in 2021.[53]

In 2021, 15.2% of the population was under 15 years of age, and 16.6% was 65 years and over. The median age in Mississauga was 40.8.[54]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Panethnic group |

2021[55] | 2016[56] | 2011[57] | 2006[58] | 2001[59] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |||||

| European[c] | 267,790 | 37.57% | 302,370 | 42.26% | 324,655 | 45.81% | 336,755 | 50.59% | 362,430 | 59.34% | ||||

| South Asian | 180,800 | 25.36% | 165,765 | 23.17% | 154,210 | 21.76% | 134,750 | 20.24% | 91,150 | 14.92% | ||||

| East Asian[d] | 60,035 | 8.42% | 62,150 | 8.69% | 58,515 | 8.26% | 55,410 | 8.32% | 43,110 | 7.06% | ||||

| Southeast Asian[e] | 55,500 | 7.79% | 51,365 | 7.18% | 55,550 | 7.84% | 44,865 | 6.74% | 34,630 | 5.67% | ||||

| Middle Eastern[f] | 51,315 | 7.2% | 44,110 | 6.17% | 32,825 | 4.63% | 22,800 | 3.43% | 15,615 | 2.56% | ||||

| Black | 49,220 | 6.9% | 47,005 | 6.57% | 44,775 | 6.32% | 41,365 | 6.21% | 37,850 | 6.2% | ||||

| Latin American | 17,325 | 2.43% | 16,110 | 2.25% | 15,360 | 2.17% | 12,410 | 1.86% | 9,265 | 1.52% | ||||

| Indigenous | 3,555 | 0.5% | 4,175 | 0.58% | 3,200 | 0.45% | 2,475 | 0.37% | 2,055 | 0.34% | ||||

| Other/Multiracial[g] | 27,300 | 3.83% | 22,420 | 3.13% | 19,635 | 2.77% | 14,815 | 2.23% | 14,705 | 2.41% | ||||

| Total responses | 712,825 | 99.28% | 715,475 | 99.15% | 708,725 | 99.34% | 665,655 | 99.57% | 610,815 | 99.66% | ||||

| Total population | 717,961 | 100% | 721,599 | 100% | 713,443 | 100% | 668,549 | 100% | 612,925 | 100% | ||||

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Religion

[edit]

The 2021 census found the most reported religion in the city to be Christianity (49.9%), with Catholicism (30.4%) making up the largest denomination, followed by Orthodox (3.6%), Anglicanism (2.0%), United Church (1.5%), Pentecostal and other Charismatic churches (1.2%), and other denominations. The next most reported religions were Islam (17.0%), Hinduism (8.8%) Sikhism (3.4%), Buddhism (2.0%), and Judaism (0.2%). Those who claimed no religious affiliation made up 18.1% of the population.[61]

| Religious group |

2021[55] | 2011[57] | 2001[59] | 1991[62] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| 355,735 | 49.9% | 424,715 | 59.93% | 427,725 | 70.03% | 365,665 | 79.25% | |

| 120,965 | 16.97% | 84,325 | 11.9% | 41,845 | 6.85% | 12,260 | 2.66% | |

| 62,520 | 8.77% | 49,325 | 6.96% | 29,165 | 4.77% | 12,185 | 2.64% | |

| 24,505 | 3.44% | 23,995 | 3.39% | 23,425 | 3.84% | 12,560 | 2.72% | |

| 14,300 | 2.01% | 15,615 | 2.2% | 11,600 | 1.9% | 4,185 | 0.91% | |

| 1,380 | 0.19% | 1,830 | 0.26% | 1,905 | 0.31% | 1,800 | 0.39% | |

| Other religion | 4,485 | 0.63% | 3,250 | 0.46% | 2,070 | 0.34% | 1,445 | 0.31% |

| Irreligious | 128,940 | 18.09% | 105,660 | 14.91% | 73,085 | 11.97% | 51,315 | 11.12% |

| Total responses | 712,825 | 99.28% | 708,725 | 99.34% | 610,815 | 99.66% | 461,420 | 99.58% |

Language

[edit]The 2021 census found that English was the mother tongue of 44.9% of the population. The next most common mother tongues were Urdu (5.0%), Arabic (4.7%), Mandarin (3.2%), Polish (3.1%), and Punjabi (2.9%). Of the official languages, 96.5% of the population knew English and 6.8% knew French.[63]

| Mother tongue | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| English | 320,640 | 44.9 |

| Urdu | 35,995 | 5.0 |

| Arabic | 33,265 | 4.7 |

| Mandarin | 23,180 | 3.2 |

| Polish | 22,070 | 3.1 |

| Punjabi | 20,690 | 2.9 |

| Tagalog | 18,325 | 2.6 |

| Spanish | 15,765 | 2.2 |

| Cantonese | 14,830 | 2.1 |

| Portuguese | 14,050 | 2.0 |

| Hindi | 11,685 | 1.6 |

| Vietnamese | 10,355 | 1.5 |

| Tamil | 10,275 | 1.4 |

| Italian | 10,260 | 1.4 |

| Serbo-Croatian | 8,955 | 1.3 |

| Gujarati | 7,260 | 1.0 |

| French | 6,180 | 0.9 |

| Ukrainian | 5,960 | 0.8 |

| Russian | 4,615 | 0.6 |

| Korean | 4,370 | 0.6 |

Economy

[edit]Over 60 of the Fortune 500 companies base their global or Canadian head offices in Mississauga. Some of the strongest industries are pharmaceuticals, banking and finance, electronics and computers, aerospace, transportation parts and equipment industries.[64]

TD Bank also has Corporate IT development centres in the city along with Royal Bank of Canada, Purolator Inc.,[65] and Laura Secord Chocolates are headquartered in the city, and Walmart, Kellogg's, Panasonic, Hewlett-Packard, and Oracle's Canadian headquarters are also in Mississauga.[66][67][68] Regional airline Jazz operates a regional office in Mississauga.[69][70] Mississauga is also an aircraft development hub with Canadian headquarters of Aerospace companies such as Magellan Aerospace and Honeywell Aerospace.[71]

Arts and culture

[edit]Mississauga has a vibrant arts community, promoted by the Mississauga Arts Council, which holds an annual awards ceremony, called the MARTYs, to celebrate the city's entertainers, artists, filmmakers, writers, and musicians.[72]

Mississauga's largest festivities such as Canada Day Celebration, Mississauga Rotary Ribfest, Tree Lighting Ceremony, and New Year's Eve Bash generally occur in Celebration Square. The Canada Day celebration was attended by 130,000 people in 2012, the Ribfest has recorded 120,000 visitors in 2012, and the inaugural New Year's Eve in 2011 has attracted 30,000 spectators.[73][74]

One of the most anticipated events in the city is Carassauga, a festival of cultures that occurs annually during mid-May. It is the second largest cultural festival in Canada. During 2013, 4014 performances took place and 300,000 people attended.[75] Carassauga attempts to display the different cultures around the world by setting up pavilions for countries around Mississauga. Visitors get free public transportation with their ticket to tour the city and explore the different pavilions. Various countries showcase their culture through food stalls, dance performances and small vendors. The event largely takes place in the Hershey Centre.[citation needed]

There are also culture-specific festivals held in Celebration Square, including Fiesta Ng Kalayaan for the Philippines, Viet Summerfest for Vietnam, Muslimfest for the city's Muslim community, Indian festival Diwali and Mosaic Festival, which is the largest South Asian multi-disciplinary arts festival in North America.[76]

The annual Bread and Honey Festival is held in Streetsville, a district that was once an independent rural village. It is held every first weekend of June at Streetsville Memorial Park to commemorate the founding of the village. The festival was inaugurated in 1974, in response to amalgamation with the City of Mississauga.[77] Activities include the Bread and Honey Race, which raises money for charities and local hospitals.[78] It also has its own annual Canada Day celebrations, which are also held at Streetsville Memorial Park.

Port Credit, another neighbourhood that was formerly a town, holds multiple festivals throughout the year. During the summer, there are street performances on multiple venues scattered throughout the district during Buskerfest. The neighbourhood also holds a grand parade named "Paint the Town Red" during Canada Day. Finally, during August, it holds the Mississauga Waterfront Festival, which includes concerts as well as family activities. During September, the Tim Hortons Southside Shuffle is being held to celebrate the neighbourhood's Blues and Jazz Festival, which includes musical performances from local blues and jazz artists.[79][80][81]

The Malton neighbourhood, which contains a significant number of Sikhs, holds its annual Khalsa Day parade, marching between the gurdwaras in Malton (Sri Guru Singh Sabha) and in the Rexdale neighbourhood in Toronto (Sikh Spiritual Centre). This parade is attended by 100,000 people. [82]

Mississauga has a significant Jewish population, with active community classes, cultural activities and holiday celebrations.[83][84][85][86]

Library

[edit]

The Mississauga Library System is a municipally owned network of 18 libraries.

Attractions

[edit]Mississauga Celebration Square

[edit]

In 2006, with the help of Project for Public Spaces,[87] the city started hosting "My Mississauga" summer festivities at its Civic Square.[88] Mississauga planned over 60 free events to bring more people to the city square. The square was transformed and included a movable stage, a snack bar, extra seating, and sports and gaming facilities (basketball nets, hockey arena, chess and checker boards) including a skate park. Some of the events included Senior's day on Tuesday, Family day on Wednesday, Vintage car Thursdays, with the main events being the Canada Day celebration, Rotary Ribfest, Tree Lighting Ceremony, and Beachfest.

Civic Square has completed its restructuring project using federal stimulus money, which features a permanent stage, a larger ice rink (which also serves as a fountain and wading pool during the summer season), media screens, and a permanent restaurant. It officially reopened at 22 June 2011 and has since been renamed as Mississauga Celebration Square. More events have been added such as holding free outdoor live concerts, and live telecast of UEFA European Football Championship. The square also holds weekly programming such as fitness classes, amphitheatre performances and movie nights during the summer, children's activities during spring and fall, and skate parties during the winter. The opening of the square has also allowed the city to hold its first annual New Year's Eve celebration in 2011.

In October 2012, the square had attracted its one millionth visitor.[89]

Art Gallery of Mississauga

[edit]The Art Gallery of Mississauga (AGM) is a public, not-for-profit art gallery located in the Mississauga Civic Centre right on Celebration Square across from the Living Arts Centre and Square One Shopping Centre. AGM is sponsored by the City of Mississauga, Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Trillium Foundation and the Ontario Arts Council. The art gallery offers free admission and tours and is open every day. AGM has over 500 copies and is working on creating a digital gallery led by gallery assistant Aaron Guravich.[90][91]

Shopping

[edit]

Square One Shopping Centre is located in the City Centre and is the second largest shopping mall in Canada. It boasts more than 350 retail stores and services and attracts 24 million annual visitors and makes over $1 billion in annual retail sales.[92][93] It opened in 1973.[94]

Erin Mills Town Centre is the second largest mall in Mississauga. It is located in the western end of the city at Eglinton Avenue and Erin Mills Parkway and opened in 1989.[95][96]

Other shopping centres include Dixie Outlet Mall; located in the southeastern area of the city. It is Canada's largest enclosed outlet mall. It opened in 1956 when the city was still known as Toronto Township, and is Mississauga's first shopping mall. Many factory outlets of premium brands are located in this mall.[97] Heartland Town Centre is an unenclosed power centre with 180 stores and restaurants.[98] A flea market, the Fantastic Flea Market, is Mississauga's oldest flea market, and opened in 1976.

Recreation

[edit]

Recreational clubs include the Mississauga Figure Skating Club, Mississauga Synchronized Swimming Association,[99] Mississauga Canoe Club, Mississauga Scrabble Club,[100] Don Rowing Club at Port Credit, International Soccer Club Mississauga,[101] and the Mississauga Aquatic Club. There are over 481 parks and woodlands areas in Mississauga, with nearly 100 km (62 mi) of trails that users can traverse.[102] Mississauga is home to many indoor playgrounds including Kids Time Family Fun Centre, KidSports indoor playground, and Laser Quest Centre. There are over 26 major indoor playgrounds in the city of Mississauga.[103]

Kariya Park, opened in 1992, is a Japanese garden located in the City Centre. It is named after Mississauga’s sister city, Kariya, Japan.

Beaches

[edit]Since 2016, Mississauga has made immense efforts to rehabilitate its Lakeshore, with collection of garbage occurring daily, and detailed water quality monitoring taking place to ensure a safe swimming environment. As of 2024, Mississauga has some of the most pristine beaches in the Greater Toronto Area, attracting tens of thousands of locals and tourists from all over.

Within Mississauga, beaches are concentrated along the shore of Lake Ontario, with the notable exception of the Lake Aquitaine boardwalk.The most distinguished beaches are Jack Darling Memorial Park and RK McMillan Park, as well as St. Lawrence Park in Port Credit.

The images in the collage, from top left to bottom right, are: Tall Oaks Park, The Shallows at St. Lawrence Park, Jack Darling Memorial Park, and Hiawatha Park.

Sports

[edit]Mississauga's Paramount Fine Foods Centre (formerly the Hershey Centre) is the city's main sports venue. It is the home arena for the Raptors 905 of the NBA G League. The arena was originally built for Mississauga's first OHL team, the Mississauga Icedogs, before they moved to St. Catharines and became the Niagara IceDogs. The Steelheads are the rebranded Mississauga St. Michael's Majors who had moved from Toronto in 2007. The arena was formerly the home of the Mississauga MetroStars of the MASL. It formerly was the home arena for the Mississauga Power of the National Basketball League of Canada before the team dissolved in 2015 after the announcement of the Raptors 905. In 2018, Mississauga's City Council approved a motion to study the feasibility and business case for construction of a new stadium in Mississauga with the hope of gaining a new CPL Team.

Other hockey teams in Mississauga include the Mississauga Chargers of the Ontario Provincial Junior A Hockey League (who play at Port Credit Arena), and the many teams in the Greater Toronto Hockey League, Mississauga Hockey League, and Mississauga Girls Hockey League that play in the city's 13 arenas. The Mississauga Chiefs of the defunct Canadian Women's Hockey League previously played at Iceland Mississauga. In addition, there is a roller hockey team, the Mississauga Rattlers of the Great Lakes Inline Junior "A" Roller Hockey League.

Mississauga also has teams for box lacrosse (Mississauga Tomahawks of the OLA Junior A Lacrosse League), cricket (Mississauga Ramblers of the Toronto and District Cricket League, Mississauga Titans of the Etobicoke District Cricket League), and Canadian football. The Mississauga Football League (MFL) is a youth football program that is for players aged 7–17, founded in 1971. The city also has other amateur football teams in Ontario leagues: the Mississauga Warriors of the Ontario Varsity Football League and the Mississauga Demons of the Ontario Australian Football League. Mississauga's rugby players are now served by the Mississauga Blues[104] through u7 - u17 Youth And Junior Programs as well as hosting one or more Senior Men's and Senior Women's Teams.

Ringette is one of the affiliated youth groups that are allocated ice time by the City of Mississauga (Recreation and Parks Division, Community Services Department) on an allocated priority basis.[105] The Ringette program is administered by the Mississauga Ringette Association.

Mississauga Marathon, a qualifier race for the Boston Marathon, is held in Mississauga annually.[106][107]

Mississauga is also the host for the following major sports events:

- 2000 IIHF Women's World Championship (Co-host)

- 2017 ISU World Junior Synchronized Skating Championships

- 2022 Ontario Summer Games, and the Ontario ParaSport Games[108]

Government

[edit]Mississauga City Council consists of the mayor and eleven city councillors, each representing one of the city's eleven numbered wards. The former mayor, Hazel McCallion, at one time the longest-serving mayor in Canada, was succeeded by Bonnie Crombie in November 2014, who resigned in January 2024 to become the leader of the liberal party of Ontario.[109] Currently, the seat is held by Carolyn Parrish since 2024.

Wards and councillors

[edit]Council elected in the 2022 municipal election:[110]

| Councillor | Ward | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carolyn Parrish | Mayor | |

| Stephen Dasko | Ward 1 (Port Credit, Lakeview) | |

| Alvin Tedjo | Ward 2 (Clarkson, Lorne Park) | |

| Chris Fonseca | Ward 3 (Rathwood, Applewood) | |

| John Kovac | Ward 4 (City Centre) | |

| Natalie Hart | Ward 5 (Britannia Woods, Malton) | |

| Joe Horneck | Ward 6 (Erindale) | |

| Dipika Damerla | Ward 7 (Cooksville) | |

| Matt Mahoney | Ward 8 (Erin Mills) | |

| Martin Reid | Ward 9 (Meadowvale West) | |

| Sue McFadden | Ward 10 (Lisgar, Churchill Meadows) | |

| Brad Butt | Ward 11 (Streetsville-Meadowvale Village) |

The City of Mississauga has had only four mayors in its history. Martin Dobkin was the city's first mayor in 1974. He was then followed by Ron A. Searle. Searle was defeated in 1978 by then-city councillor and former mayor of Streetsville, Hazel McCallion. McCallion won 12 consecutive terms as mayor, but she chose to retire prior to the November 2014 election and was succeeded by Bonnie Crombie, who won the election.

McCallion was regarded as a force in provincial politics and often referred to as Hurricane Hazel, after the devastating 1954 storm that struck the Toronto area. McCallion won or was acclaimed in every mayoral election from 1978 to 2010, in some later elections without even campaigning. In October 2010, McCallion won her twelfth term in office with over 76% of the votes. McCallion was the nation's longest-serving mayor and was runner-up in World Mayor 2005.[111] In 2014 McCallion did not run again, but endorsed Crombie, the eventual winner who became mayor in November 2014.[109]

Provincial electoral districts

[edit]| Year | Liberal | Conservative | New Democratic | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 50% | 145,139 | 33% | 96,717 | 11% | 32,632 | 2% | 4,816 | |

| 2019 | 53% | 176,112 | 32% | 107,330 | 10% | 32,294 | 4% | 12,124 | |

| 2015 | 52% | 165,282 | 36% | 116,257 | 9% | 29,822 | 2% | 6,227 | |

| Year | PC | New Democratic | Liberal | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 44% | 94,007 | 12% | 25,698 | 36% | 76,972 | 4% | 8,601 | |

| 2018 | 42% | 113,313 | 25% | 69,501 | 27% | 75,003 | 3% | 7,535 | |

- Mississauga Centre (provincial electoral district)

- Mississauga East—Cooksville (provincial electoral district)

- Mississauga—Erin Mills (provincial electoral district)

- Mississauga—Lakeshore (provincial electoral district)

- Mississauga—Malton (provincial electoral district)

- Mississauga—Streetsville (provincial electoral district)

Federal electoral districts

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Rail

[edit]Mississauga is on three major railway lines (one each owned by the Canadian National Railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and Metrolinx). Toronto–Sarnia Via Rail trains on the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor pass through Mississauga and make request stops at Malton GO Station in the northeast of the city. Other Via Rail services stop in the neighbouring cities of Brampton, Oakville, and Toronto.

Commuter rail

[edit]Commuter rail service is provided by GO Transit, a division of Metrolinx, on the Lakeshore West, Kitchener, and Milton lines. All-day service is provided along the Lakeshore West line, while the Kitchener and Milton lines serve commuters going to and from Toronto's Union Station during rush hours.

Bus

[edit]The city's public transit service, MiWay (formerly Mississauga Transit), provides bus service along more than 60 routes across the city, and connects to commuter rail with GO Transit as well as with Brampton Transit, Oakville Transit, and the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). MiWay operates routes for both local service (branded as "MiLocal") and limited-stop service (branded as "MiExpress").

Intercity buses operated by GO Transit stop at GO Train stations throughout the city and the Square One Bus Terminal.

Mississauga Transitway

[edit]A 12-station busway similar to Ottawa's Transitway was built parallel to Highway 403 from Winston Churchill Boulevard to Renforth Avenue, via the Mississauga City Centre Transit Terminal.[114] Opened in stages, the Mississauga Transitway was completed on 22 November 2017 with the opening of the final station: Renforth. The service also connects to Kipling Subway Station in Toronto, via mixed lane traffic after Renforth station.[115]

Hurontario LRT

[edit]There are plans for the construction of an LRT line along Hurontario Street stretching from Port Credit to southern Brampton, and possibly to Brampton's downtown. The project went through the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP) which includes environmental assessment. The line will be fully funded by the provincial government, with construction set to begin in 2018. Rapid transit lines could possibly be built on some other main thoroughfares, namely Dundas Street and Lakeshore Road, but no definite dates have been set.[116]

As of 2024, progress for the Hurontario LRT is well underway, with an expected completion of late 2024 to mid-2025.

Toronto Subway

[edit]In addition to the 19 km (12 mi) light rail line, there are plans to extend Line 5 Eglinton to Renforth station and Toronto Pearson International Airport though eastern Mississauga by 2030–2031 bringing the Toronto Subway into Mississauga. There will be 4 stops in the city at Renforth Gateway connecting with the Mississauga Transitway and serving the Airport Corporate Centre, Convair serving the GTAA headquarters and airfield and aircraft maintenance areas, Silver Dart serving rental car facilities and airport hotels, and Pearson Airport serving the airport at a future transit hub.[117]

Highways

[edit]Highway 401 (or the Macdonald-Cartier Freeway, connecting Windsor to the Quebec border) passes through the city's north end. The eastern part uses the collector/express lane system and feeds into Highway 403, the main freeway in the city, which runs through the City Centre and Erin Mills areas. The Queen Elizabeth Way, the city's first freeway, runs through the southern half of the city. These three freeways each run east–west, with the exception of the 403 from the 401 to Cawthra Road, and from the 407 to QEW. North of the 401, the collector lanes of the 403 become Highway 410, which goes to Brampton. Part of Highway 409 is within the city of Mississauga, and it provides access to Pearson Airport. Two other freeways run along or close to Mississauga's municipal borders. Highway 407 runs metres from the northern city limits in a power transmission corridor and forms the city's boundary with Milton between highways 401 and 403. Highway 427 forms the Toronto-Mississauga boundary in the northeast, and is always within 2 kilometres of the boundary further south, with the exception of the area around Centennial Park.

Air

[edit]

Lester B. Pearson International Airport (YYZ), operated by the Greater Toronto Airports Authority in the northeastern part of the city, is the largest and busiest airport in Canada. In 2015, it handled 41,036,847 passengers and 443,958 aircraft movements.[118] It is a major North American global gateway, handling more international passengers than any airport in North America other than John F. Kennedy International Airport. Pearson is the main hub for Air Canada, and a hub for passenger airline WestJet and cargo airline FedEx Express. It is served by over 75 airlines, having over 180 destinations.[119]

Bicycle

[edit]In 2010, the City of Mississauga approved a Cycling Master Plan outlining a strategy to develop over 900 kilometres (560 miles) of on and off-road cycling routes in the city over the next 20 years. Over 1,000 Mississauga citizens and stakeholders contributed their thoughts and ideas to help develop this plan. The plan focuses on fostering cycling as a way of life in the city, building an integrated network of cycling routes and aims to adopt a safety first approach to cycling.[120]

As of 2024, the city has bi-directional bus lanes on most major arteries, with designated bike paths on many roads such as Eglinton Avenue, Lakeshore Road West, Burnhamthorpe Road and Derry Road, to name a few. For roads which do not have designated bike lanes, there is often signage posted as well as markings on the road, indicating that bikes are permitted to use the shoulder where available, or the right-most lane in most other situations.

Emergency services

[edit]Peel Regional Police provide policing within the city of Mississauga and airport. In addition, the Ontario Provincial Police have a Port Credit detachment in the city for patrolling provincial highways. Mississauga Fire and Emergency Services provide fire fighting services and Peel Regional Paramedic Services provides emergency medical services. Toronto Pearson also has its own fire department with two halls that service calls within the airport grounds.

Healthcare

[edit]The city's two main hospitals—Credit Valley Hospital and Mississauga Hospital—were amalgamated into the Trillium Health Partners hospital group in December 2011. The health system and the administration for students in Mississauga was the property of the Peel District School Board Health Centre[121] and the health support for citizens in Mississauga was the property of Peel Health Centre.[122] The eastern part of Mississauga was the property of Pearson Health (Greater Toronto Area Health Department).[123]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary education

[edit]Mississauga is served by the Peel District School Board, which operates the secular Anglophone public schools, the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board, which operates Catholic Anglophone public schools, the Conseil scolaire Viamonde, which operates secular Francophone schools, and the Conseil scolaire de district catholique Centre-Sud, which operates Catholic Francophone schools. Within the city, the four boards run a total of more than 150 schools.

Multiple schools in Mississauga also offer specialized programs:

- French immersion schools in multiple locations across the city such as Applewood Heights Secondary School, Clarkson Secondary School and Streetsville Secondary School

- Extended French Program at St. Thomas More School, Lorne Park Secondary School, Philip Pocock Catholic Secondary School and St. Aloysius Gonzaga Secondary School

- Regional Arts Program at Queen Elizabeth Senior Public School, Cawthra Park Secondary School and Iona Catholic Secondary School

- International Business and Technology Program at Allan A. Martin Senior Public School and Gordon Graydon Memorial Secondary School

- International Baccalaureate Program at St. Francis Xavier Secondary School, Glenforest Secondary School, Bronte College and Erindale Secondary School.

- Sci Tech Program at Tomken Road Middle School and Port Credit Secondary School

- Regional Enhanced Program at Glenforest Secondary School, The Woodlands School and Lorne Park Secondary School.

- Regional Sports Program at Applewood Heights Secondary School[124]

- International and Executive Leadership Academy at TL Kennedy Secondary School

Postsecondary education

[edit]Universities

[edit]

The city is the home to the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM), the second-largest of three campuses that make up the University of Toronto's tri-campus system. U of T is the largest post-secondary institution in Canada, and its Mississauga campus has an enrolment of over 17,000 students,[125] growing at a rate of about 1,000 students per year since 2002. The campus is located in the Erindale neighbourhood on the bank of the Credit River on 225 acres of protected forest.[126] It hosts 15 academic departments, more than 180 programs in 90 areas of study, and includes institutes for Management and Innovation as well as Communication, Culture, Information and Technology. The Mississauga Academy of Medicine, opened in 2011, is based at the Terrence Donnelly Health Sciences Complex on campus, as a partnership between the university's Temerty Faculty of Medicine and Trillium Health Partners.[127] UTM employs over 3,400 full- and part-time employees (including 1,250 permanent faculty and staff), and has more than 69,000 alumni all over the world, including astronaut Roberta Bondar, filmmaker Richie Mehta, actor Zaib Shaikh, and writer/poet Dionne Brand. Recent expansions include the $35-million Innovation Complex, which opened in September 2014 and houses the Institute for Management and Innovation, and the multi-phase North Building reconstruction, now known as Deerfield Hall and Maanjiwe nendamowinan, opened in September 2014 and 2018 respectively. The latter is a $89 million 210,000 square foot, six-storey facility which houses several academic departments, lecture halls, and study spaces.[128]

Colleges

[edit]

Sheridan College opened its $46 million Hazel McCallion Campus in Mississauga in 2011. The facility has two main concentrations: business education, and programs to accelerate the movement of new Canadians into the workforce. The 150,000 sq ft (14,000 m2) campus is located on an 8.5-acre (34,000 m2) parcel of land in City Centre near Square One just north of the Living Arts Centre. The campus accommodated 1,700 students upon completion of phase one of construction in Fall 2011. Phase two of construction after 2011 increased capacity by 3,740 students to a combined total of 5,000; it also included construction of a 10-level municipal parking garage.[129][130][131][132]

Media

[edit]Mississauga is part of the Toronto media market and is served by media based in Toronto, with markets in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) that cover most of the news in the GTA. Examples of this being the majority of radio stations transmitting from the nearby CN Tower in Toronto. However, Mississauga also has The Mississauga News, a regional newspaper that is published two days a week in print and daily online.[133] There is also the Sunday Times, a community newspaper for the South Asian community that is published weekly in print and also available online, as well as Modern Mississauga, a bi-monthly general-interest print and digital magazine.[134]

The city also has three local radio stations:

- AM 960 CKNT, local news/talk radio

- AM 1650 CINA, multicultural station mainly targeted to Indian and Pakistani audiences.

- FM 91.9 CFRE, the campus radio station of the University of Toronto Mississauga.

The following national cable television stations also broadcast from Mississauga:

- Rogers Television, community channel

- The Shopping Channel, broadcasts nationally from Mississauga

- The Weather Network, broadcast nationally from Mississauga 1998–2005

- Bite TV, Canada's first interactive television station.

Sister cities

[edit]Mississauga has one sister city:

Both cities have a park and road named after each other.

- Mississauga: Kariya Park (opened July, 1992), and Kariya Drive

- Kariya: Mississauga Park (opened 2001), Mississauga Dori & Mississauga Bridge

The Mississauga Friendship Association (MFA) was established in 1993 to assist with the city's twinning program.[136]

Notable people

[edit]Freedom of the City

[edit]The Freedom of the City is the highest honour that a Canadian municipality can bestow on an individual or military unit. The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Mississauga.

Individuals

[edit]- Hazel McCallion CM OOnt: 12 April 2017.[137][138]

- Bianca Andreescu: 15 September 2019.[139][140]

- Mohamad Fakih: 15 November 2019.[141]

- Members of the band Triumph (Rik Emmett, Mike Levine and Gil Moore): 25 November 2019.[142]

Military units

[edit]- The Lorne Scots (infantry regiment): 2 July 2014.[143]

- The Toronto Scottish Regiment: 20 September 2014.[144]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˌmɪsɪˈsɔːɡə/ ⓘ MISS-ih-SAW-gə

- ^ The unannexed portion of northern Oakville became part of Milton on the same day

- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Census Profile, 2021 Census Mississauga Population". Census Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Demonyms—From coast to coast to coast — Language articles — Language Portal of Canada". Noslangues-ourlanguages.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Mississauga (Code 3521005) Census Profile". 2016 census. Government of Canada - Statistics Canada.

- ^ "Mississauga, City Ontario (Census Subdivision)". Census Profile. Statistics Canada. February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ "Three large urban areas: the Montreal and Vancouver CMAs and the Greater Golden Horseshoe". Statistics Canada, 2007 Census of Population. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 15, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

Mississauga (668,549), a suburb of Toronto...

- ^ "Downtown21 Master Plan" (PDF). City of Mississauga. April 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "Mississauga City Centre Urban Growth Centre". Government of Ontario. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Founding Villages – Heritage Mississauga". Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Mississauga | The Canadian Encyclopedia". Thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "History of Mississauga" (PDF). 5.mississauga.ca. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "About Peel". Peelarchivesblog.com. May 8, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Kucharski, Monica (June 14, 2018). "Major League Baseball drafts two Mississauga natives". Yoursauga.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "HI-LO – Ontario Archaeological Society: London Chapter". Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith, David G. (2002). "Ten Thousand Years". In Dieterman, Frank A. (ed.). Mississauga: The First 10,000 Years. Toronto: Eastendbooks. pp. 55–72. ISBN 1-896973-28-0.

- ^ a b Smith, Donald B. (2002). "Their century and a half on the Credit: The Mississaugas in Mississauga". In Dieterman, Frank A. (ed.). Mississauga: The First 10,000 Years. Toronto: Eastendbooks. pp. 107–119. ISBN 1-896973-28-0.

- ^ "Huron-Wendat | The Canadian Encyclopedia". Thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b McDonnell, Michael A. (2016). Masters of empire : Great Lakes Indians and the making of America. New York. ISBN 978-0-8090-6800-5. OCLC 932060403.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Mississauga Heritage". City of Mississauga. Retrieved April 24, 2006.

- ^ "City History". Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Part One 1819–1850" (PDF). Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ a b "Mississauga Real Estate" (PDF). Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ "Heritage Mississauga – History". Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Cook, Dave (2010). Fading History Vol. 2. Mississauga, Ontario: David L. Cook. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-9734265-3-3.

- ^ Hrabluk, Lisa (October 29, 2024). "Chapter 26: Toronto Township into Mississauga". visitmississauga.ca.

- ^ Hrabluk, Lisa. "Chapter 32: Harold Shipp". visitmississauga.ca.

- ^ Hicks, Kathleen A. (2005). Malton: Farms to Flying P. 173 (PDF). Friends of the Mississauga Library System.

- ^ "Mississauga Data: Planning District Summary (2005) P. 3" (PDF). City of Mississauga. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ staff, PAMA (January 2, 2018). "Leepkroy? Xebec? Weird names could have been called".

- ^ "Vote today at Oakville". Hamilton Spectator. December 11, 1967. p. 12. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "Preserve Our Heritage: Lost Villages". Heritage Mississauga. Mississauga Heritage Foundation. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Brampton's historic Churchville village turns 200". Pam Douglas. Brampton Guardian. July 28, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "1968 – Amalgamation to form the Town of Mississauga". Mississauga.ca. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ "Mississauga Train Derailment". Mississauga.ca. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ "Mississauga train derailment, November 10, 1979". Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Hicks, Kathleen A. (2006). Malton: Farms to Flying. Mississauga: Friends of the Mississauga Library System. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-9697873-9-6.

- ^ "Home – Welcome to the City of Mississauga". Mississauga.ca. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Feds offer to settle land claims". Mississauga News. January 27, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Community Profile, City of Mississauga". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ "Mississauga's Natural Areas" (PDF). 5.mississauga.ca. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Campion-Smith, Bruce (June 4, 2008). "Air France sues over crash". Toronto Star. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Severe Thunderstorms and Heavy Rain Cause Local Flooding and Closures". gtamoldremoval.com. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Neighbourhoods" (PDF). Mississauga Official Plan–Part 3. City of Mississauga. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "About Mississauga: Weather". City of Mississauga. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ "Plant Hardiness Zone by Municipality". Plant Hardiness of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved September 7, 2025.

- ^ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Toronto Lester B. Pearson INT'L A". 1981–2010 Canadian Climate Normals. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Tornado F0, Ontario 1923-6-24 #23". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ "Mississauga Climate History". Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Tornado F0, Ontario 1923-6-24 #23". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Toronto Lester B. Pearson International Airport". 1991-2020 Canadian Climate Normals. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Toronto Lester B. Pearson INT'L A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for November 2022". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 9, 2022). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Mississauga, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 27, 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (November 27, 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 20, 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 2, 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Multiple ethnic/cultural origins can be reported

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 9, 2022). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Mississauga, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. "1991 Census of Canada: Census Area Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 9, 2022). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Mississauga, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ City of Mississauga Economic Development Office (December 7, 2011). "City of Mississauga – Leading Businesses in Our Community" (PDF). City of Mississauga. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Purolator Facts & History". Purolator. Purolator Inc. November 19, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Company Profile" Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Walmart Canada. Retrieved on 24 July 2012.

- ^ You Might Also Like (June 9, 2011). "Target Canada's headquarters to be in Mississauga, Ont". Canadiangrocer.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Office Locations." Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved on 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 16 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine." Air Canada Jazz. Retrieved on 19 May 2009.

- ^ Our Offices Archived 5 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Kam Air North America. Retrieved on 18 May 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us". Magellan Aerospace. Magellan. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ "MARTYS | Mississauga Arts Council". Mississaugaartscouncil.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Mississauga Ribfest » About". Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Paterson, David (July 16, 2014). "A Mississauga Ribfest Experience". Mississauga News. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Carassauga by the Numbers". Carassauga.com. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ "Mississauga Celebration Square – About the Square". Mississauga.ca. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "The Story of Streetsville". Streetsville Founders' Bread and Honey Festival Inc. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Untitled". Streetsville Founders' Bread and Honey Festival Inc. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Lindsay Cairns (July 1, 2014). "Buskerfest Returns to Port Credit". Mississauga News. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Paint The Town Red". Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Mississauga Waterfront Festival". Seetorontonow.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "100,000 turn out for Malton parade". South Asian Focus. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Kumar Agrawal, Sandeep (June 14, 2008). "Faith-based Ethnic Residential Communities and Neighbourliness in Canada". Planning Practice & Research. 23 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/02697450802076431. S2CID 128679393.

- ^ Le, Julia (February 7, 2011). "Course teaches soul-searching journey". Mississauga News.

The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute's (JLI) new course, Toward a Meaningful Life: A Soul-Searching Journey for Every Person...

- ^ Dean, Jan. "Chabad Mississauga honours builder". Mississauga News. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ Paterson, David (February 24, 2013). "Chabad marks Purim Japanese style". Mississauga News.

- ^ "Project for Public Spaces". Pps.org. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discover Mississauga – My Mississauga". Mississauga.ca. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Thanks a Million". City of Mississauga. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ "Photo Slideshow: Allegory of the Cave, Opening Reception". Mississauga Life – Spirit of the City. Mississauga Life. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "ABOUT/WHO WE ARE". Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Specialty Leasing". Square One Shopping Centre. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ "Square One Achieves $1 Billion in Annual Retail Sales". Newswire.ca. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "A Look Back at Square One 40 Years Ago | Mississauga". insauga.com. September 5, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ Erin Mills Town Centre. "Erin Mills Town Centre". Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Kovessy, Peter. "Pension Buys Mississauga Mall for $370M". Business Journal. Ottawa Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ Dixie Outlet Mall. "Dixie Outlet Mall". Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ "Interesting Facts You Never Knew About Heartland Town Centre in Mississauga". Insauga.com. November 17, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to the Mississauga Synchro Swim Association". Mssa.ca. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Mississauga Scrabble Club". Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "International Soccer Club Mississauga". Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Peel Trails Database". Walkandrollpeel.ca. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "List of Indoor Playgrounds in Mississauga, Ontario". Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ "Blues Rugby". Bluesrugby.ca. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "Corporate Policy and Procedure" (PDF). City of Mississauga.

- ^ "Mississauga Marathon". Mississauga Marathon. Landmark Sport Group Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ Pecar, Steve (August 18, 2021). "Mississauga Marathon set to return in 2022". Insauga.com. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Mississauga Hosts 2022 Ontario Parasport Games and 2022 Ontario Summer Games and Announces Volunteer Co-Chairs". City of Mississauga. September 29, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Bascaramurty, Dakshana (October 27, 2014). "Bonnie Crombie elected new mayor of Mississauga". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "World Mayor 2005 Finalists". Worldmayor.com. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Official Voting Results Raw Data (poll by poll results in Mississauga)". Elections Canada. April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ "Official Voting Results by polling station (poll by poll results in Mississauga)". Election Ontario. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ "Residents – Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Project". Mississauga.ca. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "About the Transitway". MiWay. City of Mississauga. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "Hurontario Main Street". Hurontario-main.ca. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Eglinton Crosstown West Extension - Projects". Metrolinx.com.

- ^ "Toronto Pearson traffic summary" (PDF). Greater Toronto Airports Authority. February 2, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Transportation" (PDF). Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Mississauga Cycling Master Plan". Mississaugacycling.ca. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ "Three Locations, One Standard of Care". Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Peel Public Health — Region of Peel". Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Ministry of Labour Offices". Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Peel District School Board". Peelschools.org. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Quick facts; University of Toronto". Retrieved June 9, 2025.

- ^ "Fact Sheet, 2022-2023". University of Toronto Mississauga.

- ^ "Mississauga Academy of Medicine". University of Toronto Mississauga. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ "Maanjiwe nendamowinan". University of Toronto Mississauga.

- ^ "College contract awarded". Mississauga News. December 24, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Ground broken for college campus". Mississauga News. December 15, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "City approves Sheridan lease". Mississauga News. October 29, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "City to get Sheridan College campus". Mississauga News. May 25, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Metroland.com – The Mississauga News". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Modern Mississauga". Modernmississauga.com. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ^ "Sister City". Mississauga.ca. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ "About | Mississauga Friendship Association (MFA)". MFA-Official Live. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Newport, Ashley (April 12, 2017). "Hazel McCallion Set to Receive Key to the City of Mississauga". Insauga.com.

- ^ "SPEECH: Hazel McCallion Presented Key to the City by Mayor Crombie | Mayor Crombie". Mayorcrombie.ca. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Bianca Andreescu being honoured with celebration in Mississauga". Global News. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ "Mississauga Mayor Bonnie Crombie to Present Bianca Andreescu With Key to the City | inSauga". Insauga.com. September 8, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Mississauga Mayor Bonnie Crombie Presents Dr. Mohamad Fakih with the Key to the City". Mississauga.ca. November 15, 2019.

- ^ "Mississauga Mayor Presents Keys to the City to Members of the band Triumph". Mississauga.ca. November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Lorne Scots Awarded the Freedom of the City of Mississauga". Lornescots.ca. July 2, 2014.

- ^ "Freedom of the City of Mississauga Parade on September 20, 2014". Mississauga.com.

External links

[edit]- Official website

Mississauga travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mississauga travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mississauga

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Origins and evolution of the name

The name "Mississauga" originates from the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) term misi-zaagiing, translating to "[those at the] great river-mouth," a descriptor applied to the Indigenous people inhabiting the region near the mouth of a significant waterway.[10][11] This etymology likely references the Credit River's outlet into Lake Ontario, where the Mississaugas of the Credit—a band of Anishinaabe—established seasonal and semi-permanent settlements for fishing and trade by the early 18th century.[12] Alternative interpretations link it to miswe-zaagiing, denoting "a river with many outlets" or "river of many mouths," reflecting the delta-like features of rivers such as the Credit or earlier habitats like the Trent River system, from which the band migrated westward around 1700.[13][14] The term first appeared in European records in 1640, when Jesuit missionaries documented it as "oumisagai" or a variant, identifying it with Anishinaabe groups in the Great Lakes region rather than a specific clan or fixed locale.[12] By the mid-18th century, British colonial administrators consistently used "Mississauga" in treaties and land records to denote the Credit River band, as in the 1763 Treaty of Oswegatchie and subsequent purchases like the 1805 Toronto Purchase, distinguishing them from other Anishinaabe subgroups.[15] This usage persisted through Canadian confederation, with minimal phonetic alteration to preserve the original Anishinaabe phonology—unlike more heavily anglicized Indigenous names—ensuring continuity in official nomenclature for the First Nation and, later, the adjacent municipality incorporated in 1974.[13]History

Pre-Columbian Indigenous eras

The territory encompassing modern Mississauga exhibits archaeological traces of Paleo-Indian occupation dating to approximately 10,000–8,000 BCE, marked by fluted spear points and scrapers adapted for big-game hunting in a post-glacial landscape.[16] These artifacts, recovered from regional sites including the Credit River valley, reflect small, nomadic bands exploiting megafauna and seasonal resources amid retreating ice sheets.[17] [18] During the Archaic period (ca. 8,000–1,000 BCE), evidence shifts to broader tool assemblages, including ground-stone axes, atlatls, and netsinkers, signaling intensified fishing, foraging, and seasonal camps along riverine corridors like the Credit River.[19] Excavations in the area have yielded such implements from terrace sites near stream confluences, indicating adaptive strategies to warming climates and diverse flora-fauna, without signs of permanent settlement.[16][20] The Woodland period (ca. 1,000 BCE–1,650 CE) introduced cord-marked pottery and burial mounds, with Late Woodland phases (ca. 500–1,650 CE) showing village formations and maize horticulture under Iroquoian cultural patterns, evidenced by longhouse post molds and corn-bean remains at southern Ontario sites proximate to Mississauga.[21][22] Archaeological surveys in the Credit River watershed have documented multi-component sites with these features, alongside Anishinaabe-influenced mobility patterns, though Iroquoian village clusters dominate the empirical record for intensive land use prior to European arrival.[17][23] Such findings underscore hunter-horticultural economies reliant on river valleys for trade and subsistence, based solely on excavated material culture rather than later narratives.[18]European contact and colonial settlements