Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Soil salinity control

View on WikipediaThis article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (February 2020) |

Soil salinity control refers to controlling the process and progress of soil salinity to prevent soil degradation by salination and reclamation of already salty (saline) soils. Soil reclamation is also known as soil improvement, rehabilitation, remediation, recuperation, or amelioration.

The primary man-made cause of salinization is irrigation. River water or groundwater used in irrigation contains salts, which remain in the soil after the water has evaporated.

The primary method of controlling soil salinity is to permit 10–20% of the irrigation water to leach the soil, so that it will be drained and discharged through an appropriate drainage system. The salt concentration of the drainage water is normally 5 to 10 times higher than that of the irrigation water which meant that salt export will more closely match salt import and it will not accumulate.

Problems with soil salinity

[edit]Salty (saline) soils have high salt content. The predominant salt is normally sodium chloride (NaCl, "table salt"). Saline soils are therefore also sodic soils but there may be sodic soils that are not saline, but alkaline.

This damage is an average of 2,000 hectares of irrigated land in arid and semi-arid areas daily for more than 20 years across 75 countries (each week the world loses an area larger than Manhattan)...To feed the world's anticipated nine billion people by 2050, and with little new productive land available, it's a case of all lands needed on deck.—principal author Manzoor Qadir, Assistant Director, Water and Human Development, at UN University's Canadian-based Institute for Water, Environment and Health[1]

According to a study by UN University, about 62 million hectares (240 thousand square miles; 150 million acres), representing 20% of the world's irrigated lands are affected, up from 45 million ha (170 thousand sq mi; 110 million acres) in the early 1990s.[1] In the Indo-Gangetic Plain, home to over 10% of the world's population, crop yield losses for wheat, rice, sugarcane and cotton grown on salt-affected lands could be 40%, 45%, 48%, and 63%, respectively.[1]

Salty soils are a common feature and an environmental problem in irrigated lands in arid and semi-arid regions, resulting in poor or little crop production.[2] The causes of salty soils are often associated with high water tables, which are caused by a lack of natural subsurface drainage to the underground. Poor subsurface drainage may be caused by insufficient transport capacity of the aquifer or because water cannot exit the aquifer, for instance, if the aquifer is situated in a topographical depression.

Worldwide, the major factor in the development of saline soils is a lack of precipitation. Most naturally saline soils are found in (semi) arid regions and climates of the earth.

Primary cause

[edit]

Man-made salinization is primarily caused by salt found in irrigation water. All irrigation water derived from rivers or groundwater, regardless of water purity, contains salts that remain behind in the soil after the water has evaporated.

For example, assuming irrigation water with a low salt concentration of 0.3 g/L (equal to 0.3 kg/m3 corresponding to an electric conductivity of about 0.5 FdS/m) and a modest annual supply of irrigation water of 10,000 m3/ha (almost 3 mm/day) brings 3,000 kg salt/ha each year. With the absence of sufficient natural drainage (as in waterlogged soils), and proper leaching and drainage program to remove salts, this would lead to high soil salinity and reduced crop yields in the long run.

Much of the water used in irrigation has a higher salt content than 0.3 g/L, compounded by irrigation projects using a far greater annual supply of water. Sugar cane, for example, needs about 20,000 m3/ha of water per year. As a result, irrigated areas often receive more than 3,000 kg/ha of salt per year, with some receiving as much as 10,000 kg/ha/year.

Secondary cause

[edit]The secondary cause of salinization is waterlogging in irrigated land. Irrigation causes changes to the natural water balance of irrigated lands. Large quantities of water in irrigation projects are not consumed by plants and must go somewhere. In irrigation projects, it is impossible to achieve 100% irrigation efficiency where all the irrigation water is consumed by the plants. The maximum attainable irrigation efficiency is about 70%, but usually, it is less than 60%. This means that minimum 30%, but usually more than 40% of the irrigation water is not evaporated and it must go somewhere.

Most of the water lost this way is stored underground which can change the original hydrology of local aquifers considerably. Many aquifers cannot absorb and transport these quantities of water, and so the water table rises leading to waterlogging.

Waterlogging causes three problems:

- The shallow water table and lack of oxygenation of the root zone reduces the yield of most crops.

- It leads to an accumulation of salts brought in with the irrigation water as their removal through the aquifer is blocked.

- With the upward seepage of groundwater, more salts are brought into the soil and the salination is aggravated.

Aquifer conditions in irrigated land and the groundwater flow have an important role in soil salinization,[3] as illustrated here:

- Illustration of the influence of aquifer conditions on soil salinization in irrigated land

-

Soil salinization in the lower parts of undulating land with a good aquifer

-

Soil salinization in the unirrigated parts of flat land with a good aquifer

-

Soil salinization in irrigated flat land without an aquifer

-

Soil salinization in a coastal delta from irrigation higher up

Salt affected area

[edit]Normally, the salinization of agricultural land affects a considerable area of 20% to 30% in irrigation projects. When the agriculture in such a fraction of the land is abandoned, a new salt and water balance is attained, a new equilibrium is reached and the situation becomes stable.

In India alone, thousands of square kilometers have been severely salinized. China and Pakistan do not lag far behind (perhaps China has even more salt affected land than India). A regional distribution of the 3,230,000 km2 of saline land worldwide is shown in the following table derived from the FAO/UNESCO Soil Map of the World.[4]

| Region | Area (106ha) |

|---|---|

| Australia | 84.7 |

| Africa | 69.5 |

| Latin America | 59.4 |

| Near and Middle East | 53.1 |

| Europe | 20.7 |

| Asia and Far East | 19.5 |

| Northern America | 16.0 |

Spatial variation

[edit]Although the principles of the processes of salinization are fairly easy to understand, it is more difficult to explain why certain parts of the land suffer from the problems and other parts do not, or to predict accurately which part of the land will fall victim. The main reason for this is the variation of natural conditions in time and space, the usually uneven distribution of the irrigation water, and the seasonal or yearly changes of agricultural practices. Only in lands with undulating topography is the prediction simple: the depressional areas will degrade the most.

The preparation of salt and water balances[3] for distinguishable sub-areas in the irrigation project, or the use of agro-hydro-salinity models,[5] can be helpful in explaining or predicting the extent and severity of the problems.

Diagnosis

[edit]

Measurement

[edit]Soil salinity is measured as the salt concentration of the soil solution in tems of g/L or electric conductivity (EC) in dS/m. The relation between these two units is about 5/3: y g/L => 5y/3 dS/m. Seawater may have a salt concentration of 30 g/L (3%) and an EC of 50 dS/m.

The standard for the determination of soil salinity is from an extract of a saturated paste of the soil, and the EC is then written as ECe. The extract is obtained by centrifugation. The salinity can more easily be measured, without centrifugation, in a 2:1 or 5:1 water:soil mixture (in terms of g water per g dry soil) than from a saturated paste. The relation between ECe and EC2:1 is about 4, hence: ECe = 4EC1:2.[8]

Classification

[edit]Soils are considered saline when the ECe > 4.[9] When 4 < ECe < 8, the soil is called slightly saline, when 8 < ECe < 16 it is called (moderately) saline, and when ECe > 16 severely saline.

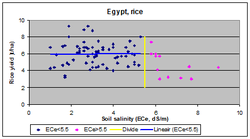

Crop tolerance

[edit]Sensitive crops lose their vigor already in slightly saline soils; most crops are negatively affected by (moderately) saline soils, and only salinity resistant crops thrive in severely saline soils. The University of Wyoming[10] and the Government of Alberta[11] report data on the salt tolerance of plants.

Principles of salinity control

[edit]Drainage is the primary method of controlling soil salinity. The system should permit a small fraction of the irrigation water (about 10 to 20 percent, the drainage or leaching fraction) to be drained and discharged out of the irrigation project.[12]

In irrigated areas where salinity is stable, the salt concentration of the drainage water is normally 5 to 10 times higher than that of the irrigation water. Salt export matches salt import and salt will not accumulate.

When reclaiming already salinized soils, the salt concentration of the drainage water will initially be much higher than that of the irrigation water (for example 50 times higher). Salt export will greatly exceed salt import, so that with the same drainage fraction a rapid desalinization occurs. After one or two years, the soil salinity is decreased so much, that the salinity of the drainage water has come down to a normal value and a new, favorable, equilibrium is reached.

In regions with pronounced dry and wet seasons, the drainage system may be operated in the wet season only, and closed during the dry season. This practice of checked or controlled drainage saves irrigation water.

The discharge of salty drainage water may pose environmental problems to downstream areas. The environmental hazards must be considered very carefully and, if necessary mitigating measures must be taken. If possible, the drainage must be limited to wet seasons only, when the salty effluent inflicts the least harm.

Drainage systems

[edit]

Land drainage for soil salinity control is usually by horizontal drainage system (figure left), but vertical systems (figure right) are also employed.

The drainage system designed to evacuate salty water also lowers the water table. To reduce the cost of the system, the lowering must be reduced to a minimum. The highest permissible level of the water table (or the shallowest permissible depth) depends on the irrigation and agricultural practices and kind of crops.

In many cases a seasonal average water table depth of 0.6 to 0.8 m is deep enough. This means that the water table may occasionally be less than 0.6 m (say 0.2 m just after an irrigation or a rain storm). This automatically implies that, in other occasions, the water table will be deeper than 0.8 m (say 1.2 m). The fluctuation of the water table helps in the breathing function of the soil while the expulsion of carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by the plant roots and the inhalation of fresh oxygen (O2) is promoted.

The establishing of a not-too-deep water table offers the additional advantage that excessive field irrigation is discouraged, as the crop yield would be negatively affected by the resulting elevated water table, and irrigation water may be saved.

The statements made above on the optimum depth of the water table are very general, because in some instances the required water table may be still shallower than indicated (for example in rice paddies), while in other instances it must be considerably deeper (for example in some orchards). The establishment of the optimum depth of the water table is in the realm of agricultural drainage criteria.[13]

Soil leaching

[edit]

The vadose zone of the soil below the soil surface and the water table is subject to four main hydrological inflow and outflow factors:[3]

- Infiltration of rain and irrigation water (Irr) into the soil through the soil surface (Inf) :

- Inf = Rain + Irr

- Evaporation of soil water through plants and directly into the air through the soil surface (Evap)

- Percolation of water from the unsaturated zone soil into the groundwater through the watertable (Perc)

- Capillary rise of groundwater moving by capillary suction forces into the unsaturated zone (Cap)

In steady state (i.e. the amount of water stored in the unsaturated zone does not change in the long run) the water balance of the unsaturated zone reads: Inflow = Outflow, thus:

- Inf + Cap = Evap + Perc or:

- Irr + Rain + Cap = Evap + Perc

and the salt balance is

- Irr.Ci + Cap.Cc = Evap.Fc.Ce + Perc.Cp + Ss

where Ci is the salt concentration of the irrigation water, Cc is the salt concentration of the capillary rise, equal to the salt concentration of the upper part of the groundwater body, Fc is the fraction of the total evaporation transpired by plants, Ce is the salt concentration of the water taken up by the plant roots, Cp is the salt concentration of the percolation water, and Ss is the increase of salt storage in the unsaturated soil. This assumes that the rainfall contains no salts. Only along the coast this may not be true. Further it is assumed that no runoff or surface drainage occurs. The amount of removed by plants (Evap.Fc.Ce) is usually negligibly small: Evap.Fc.Ce = 0

The salt concentration Cp can be taken as a part of the salt concentration of the soil in the unsaturated zone (Cu) giving: Cp = Le.Cu, where Le is the leaching efficiency. The leaching efficiency is often in the order of 0.7 to 0.8,[14] but in poorly structured, heavy clay soils it may be less. In the Leziria Grande polder in the delta of the Tagus river in Portugal it was found that the leaching efficiency was only 0.15.[15]

Assuming that one wishes to avoid the soil salinity to increase and maintain the soil salinity Cu at a desired level Cd we have:

Ss = 0, Cu = Cd and Cp = Le.Cd. Hence the salt balance can be simplified to:

- Perc.Le.Cd = Irr.Ci + Cap.Cc

Setting the amount percolation water required to fulfill this salt balance equal to Lr (the leaching requirement) it is found that:

- Lr = (Irr.Ci + Cap.Cc) / Le.Cd .

Substituting herein Irr = Evap + Perc − Rain − Cap and re-arranging gives :

- Lr = [ (Evap−Rain).Ci + Cap(Cc−Ci) ] / (Le.Cd − Ci)[12]

With this the irrigation and drainage requirements for salinity control can be computed too.

In irrigation projects in (semi)arid zones and climates it is important to check the leaching requirement, whereby the field irrigation efficiency (indicating the fraction of irrigation water percolating to the underground) is to be taken into account.

The desired soil salinity level Cd depends on the crop tolerance to salt. The University of Wyoming,[10] US, and the Government of Alberta,[11] Canada, report crop tolerance data.

Strip cropping: an alternative

[edit]

In irrigated lands with scarce water resources suffering from drainage (high water table) and soil salinity problems, strip cropping is sometimes practiced with strips of land where every other strip is irrigated while the strips in between are left permanently fallow.[16]

Owing to the water application in the irrigated strips they have a higher water table which induces flow of groundwater to the unirrigated strips. This flow functions as subsurface drainage for the irrigated strips, whereby the water table is maintained at a not-too-shallow depth, leaching of the soil is possible, and the soil salinity can be controlled at an acceptably low level.

In the unirrigated (sacrificial) strips the soil is dry and the groundwater comes up by capillary rise and evaporates leaving the salts behind, so that here the soil salinizes. Nevertheless, they can have some use for livestock, sowing salinity resistant grasses or weeds. Moreover, useful salt resistant trees can be planted like Casuarina, Eucalyptus, or Atriplex, keeping in mind that the trees have deep rooting systems and the salinity of the wet subsoil is less than of the topsoil. In these ways wind erosion can be controlled. The unirrigated strips can also be used for salt harvesting.[citation needed]

Soil salinity models

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding missing information. (October 2007) |

The majority of the computer models available for water and solute transport in the soil (e.g. SWAP,[17] DrainMod-S,[18] UnSatChem,[19] and Hydrus[20]) are based on Richard's differential equation for the movement of water in unsaturated soil in combination with Fick's differential convection–diffusion equation for advection and dispersion of salts.

The models require the input of soil characteristics like the relations between variable unsaturated soil moisture content, water tension, water retention curve, unsaturated hydraulic conductivity, dispersity, and diffusivity. These relations vary greatly from place to place and time to time and are not easy to measure. Further, the models are complicated to calibrate under farmer's field conditions because the soil salinity here is spatially very variable. The models use short time steps and need at least a daily, if not hourly, database of hydrological phenomena. Altogether, this makes model application to a fairly large project the job of a team of specialists with ample facilities.

Simpler models, like SaltMod,[5] based on monthly or seasonal water and soil balances and an empirical capillary rise function, are also available. They are useful for long-term salinity predictions in relation to irrigation and drainage practices.

LeachMod,[21][22] Using the SaltMod principles helps in analyzing leaching experiments in which the soil salinity was monitored in various root zone layers while the model will optimize the value of the leaching efficiency of each layer so that a fit is obtained of observed with simulated soil salinity values.

Spatial variations owing to variations in topography can be simulated and predicted using salinity cum groundwater models, like SahysMod.

See also

[edit]- Alkali soils – Soil type with pH > 8.5

- Biosalinity – Use of salty water for irrigation

- Crop tolerance to seawater – Quality in crops

- Desalination – Removal of salts from water

- Halophyte – Salt-tolerant plant

- Halotolerance – Adaptation to high salinity

- Salt tolerance of crops

- Sodium in biology – Use of sodium by organisms

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "World losing 2,000 hectares of farm soil daily to salt damage".

- ^ I.P. Abrol, J.S.P Yadav, and F. Massoud 1988. Salt affected soils and their management, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Soils Bulletin 39.

- ^ a b c ILRI, 2003. Drainage for Agriculture: Drainage and hydrology/salinity - water and salt balances. Lecture notes International Course on Land Drainage, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. Download from page : [1], or directly as PDF : [2]

- ^ R. Brinkman, 1980. Saline and sodic soils. In: Land reclamation and water management, p. 62-68. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ^ a b SaltMod: a tool for interweaving of irrigation and drainage for salinity control. In: W.B.Snellen (ed.), Towards integration of irrigation, and drainage management. ILRI Special report, p. 41-43. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ^ H.J. Nijland and S. El Guindy, Crop yields, watertable depth and soil salinity in the Nile Delta, Egypt. In: Annual report 1983. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ^ On line collection of salt tolerance data of agricultural crops from measurements in farmers' fields [3]

- ^ ILRI, 2003, This paper discusses soil salinity. Lecture notes, International Course on Land Drainage International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. On line: [4]

- ^ L.A.Richards (Ed.), 1954. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils. USDA Agricultural Handbook 60. On internet

- ^ a b Alan D. Blaylock, 1994, Soil Salinity and Salt tolerance of Horticultural and Landscape Plants. [5]

- ^ a b Government of Alberta, Salt tolerance of Plants

- ^ a b J.W. van Hoorn and J.G. van Alphen (2006), Salinity control. In: H.P. Ritzema (Ed.), Drainage Principles and Applications, p. 533-600, Publication 16, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-70754-33-9.

- ^ Agricultural Drainage Criteria, Chapter 17 in: H.P.Ritzema (2006), Drainage Principles and Applications, Publication 16, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 90-70754-33-9. On line : [6]

- ^ R.J.Oosterbaan and M.A.Senna, 1990. Using SaltMod to predict drainage and salinity control in the Nile delta. In: Annual Report 1989, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands, p. 63-74. See Case Study Egypt in the SaltMod manual : [7]

- ^ E.A. Vanegas Chacon, 1990. Using SaltMod to predict desalinization in the Leziria Grande Polder, Portugal. Thesis. Wageningen Agricultural University, The Netherlands

- ^ ILRI, 2000. Irrigation, groundwater, drainage and soil salinity control in the alluvial fan of Garmsar. Consultancy assignment to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement (ILRI), Wageningen, The Netherlands. Online: [8]

- ^ SWAP model

- ^ DrainMod-S model Archived 2008-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ UnSatChem model

- ^ Hydrus model

- ^ LeachMod

- ^ Reclamation of a Coastal Saline Vertisol by Irrigated Rice Cropping, Interpretation of the data with a Salt Leaching Model. In: International Journal of Environmental Science, April 2019. On line: [9]

External links

[edit]- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations on soil salinity

- US Salinity Laboratory at Riverside, California

Soil salinity control

View on GrokipediaUnderstanding Soil Salinity

Definition and Primary Causes

Soil salinity refers to the accumulation of soluble salts, such as sodium chloride (NaCl) and calcium sulfate (CaSO4), in the soil profile, which adversely affects plant growth by creating osmotic stress and ion toxicity.[6] This condition is typically quantified through the electrical conductivity of the saturation extract (ECe), with saline soils defined as those exhibiting ECe values greater than or equal to 4 dS/m at 25°C.[7][8] These salts dissolve in soil water, increasing its salinity and reducing the availability of water to plants despite adequate moisture levels.[9] Primary natural causes of soil salinity include the weathering of salt-rich parent materials, where minerals in rocks break down over time, releasing soluble salts into the soil.[10] In coastal areas, sea spray deposits sodium and chloride ions directly onto soils, contributing to salt buildup, particularly in regions with frequent marine influence.[11] Additionally, capillary rise from underlying saline groundwater transports salts upward to the root zone, especially in areas with shallow water tables and high evaporation rates.[12] These processes are exacerbated in arid regions where annual rainfall is less than 250 mm, insufficient to naturally leach salts below the root zone and leading to progressive accumulation.[2][13] Irrigation-induced salinity arises from the repeated application of water containing dissolved salts, which accumulates in the soil as water is taken up by plants or evaporates, leaving salts behind.[1] Poor-quality irrigation sources, such as brackish groundwater or river water with elevated salt content, intensify this buildup over time, particularly in intensive farming systems without adequate drainage.[14] Historically, this issue was recognized as early as circa 2000 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia, where over-irrigation led to salinization that reduced crop yields by up to 50%, contributing to the decline of early agricultural civilizations.[15]Secondary Causes and Global Extent

Secondary causes of soil salinity primarily stem from human activities that exacerbate salt accumulation in agricultural landscapes. Over-irrigation without adequate drainage is a key driver, as it raises water tables and concentrates salts through evapotranspiration in arid and semi-arid regions, leading to secondary salinization.[16][17] The use of brackish irrigation water, typically with electrical conductivity (EC) exceeding 3 dS/m, introduces soluble salts directly into the soil profile, particularly when leaching is insufficient to flush them below the root zone.[18] Deforestation further amplifies this by removing vegetative cover, which increases surface evaporation rates and promotes capillary rise of saline groundwater to the soil surface.[19] Additionally, overuse of fertilizers, especially nitrogen-based ones, contributes to salt inputs through excess application that exceeds plant uptake, resulting in residual ions that elevate soil EC over time.[20][21] Globally, salt-affected soils encompass approximately 1.381 billion hectares, representing about 10.7% of the world's land area (as of 2024), with approximately 10% of irrigated cropland—totaling around 35 million hectares—impacted by salinity.[3][22] These affected areas are disproportionately concentrated in arid and semi-arid zones, with notable hotspots in Australia (357 million hectares total salt-affected, including approximately 2 million hectares of irrigated and dryland saline soils), India (6.7 million hectares of saline soils), and the Middle East (over 50 million hectares across the region).[23][3] Projections from earlier studies indicate that more than 50% of arable land could be salinized by 2050 if current trends continue, driven by climate change factors such as rising temperatures that enhance evaporation and sea-level rise that intrudes saline water into coastal aquifers.[24][2] Spatial variations in soil salinity reflect both climatic patterns and management practices, with zonal distributions prevalent in arid and semi-arid climates where low rainfall limits natural leaching.[25] Localized hotspots often arise from poor land management, such as intensive irrigation in valleys or floodplains without drainage infrastructure. Soil texture plays a critical role in these patterns; fine-textured soils, rich in clay, retain salts more effectively due to their higher water-holding capacity and lower permeability, which hinders leaching compared to coarser sands.[26][27] This retention exacerbates salinity in poorly drained fine soils, contrasting with more uniform dispersal in permeable textures.Environmental and Agricultural Impacts

Soil salinity imposes significant constraints on agricultural productivity primarily through osmotic stress and ion toxicity. Osmotic stress arises when high salt concentrations in the soil solution lower the water potential, making it harder for plants to absorb water despite adequate soil moisture, leading to physiological water deficit and reduced growth.[2] Ion toxicity occurs as excessive sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions accumulate in plant tissues, particularly harming root functions and disrupting nutrient balance by competing with essential ions like potassium.[2] For wheat, a moderately salt-tolerant crop, yields remain unaffected up to a soil electrical conductivity (ECe) of 6 dS/m, but beyond this threshold, losses average 7.1% per additional dS/m, resulting in 10-25% reductions at moderate salinity levels around 7-9 dS/m.[28] Globally, these impacts contribute to an estimated annual economic loss of $27.3 billion (as estimated in 2013) from reduced crop production on salt-affected irrigated lands, which cover about 10% of the world's approximately 350 million hectares of irrigated area (as of 2021).[29] Environmentally, soil salinity drives biodiversity loss, particularly in wetlands where elevated salt levels alter habitat suitability and reduce species richness in aquatic and terrestrial communities.[30] It degrades soil structure by promoting dispersion of clay particles, which diminishes aggregate stability and increases susceptibility to water and wind erosion, exacerbating land degradation.[31] Salinity also contaminates groundwater through upward capillary rise of saline water tables or leaching of salts from surface soils, rendering aquifers unsuitable for irrigation or drinking and perpetuating cycles of salinization.[32] In regions like the Aral Sea basin, intensified salinity has accelerated desertification, transforming fertile deltas into barren salt flats and amplifying dust storms that further degrade surrounding ecosystems.[33] Over the long term, soil salinity creates feedback loops that worsen water scarcity, especially in climate-vulnerable arid and semi-arid areas where reduced plant transpiration lowers local humidity and rainfall efficiency, compounding drought effects.[34] As climate change intensifies evaporation and irregular precipitation, these loops accelerate salinization, further limiting freshwater availability and promoting irreversible land abandonment in affected regions.[35]Diagnosis and Classification

Field and Laboratory Measurement

Field measurements of soil salinity provide essential data for on-site assessment, enabling rapid mapping and monitoring without extensive soil disturbance. These methods primarily measure electrical conductivity (EC), which correlates with salt concentration, as higher salinity increases soil's ability to conduct electricity. Common field techniques include non-invasive and in-situ approaches that target apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) to delineate saline areas efficiently.[36] Electromagnetic induction (EMI) sensors, such as the EM38 device, offer a non-invasive method for mapping soil salinity across large fields by generating an electromagnetic field that induces currents in conductive soil layers. In vertical dipole mode, EMI typically assesses salinity to a depth of approximately 1.5 to 2 meters, with prediction accuracies often achieving coefficients of determination (R²) between 0.7 and 0.9 when calibrated against laboratory data, though errors can reach ±10% due to soil heterogeneity and texture influences.[37][38] Four-electrode probes enable direct in-situ EC measurements by inserting two current-injecting and two potential-measuring electrodes into the soil, providing bulk ECa values at specific depths with high precision for small volumes, typically within 5-10 cm of the probe tip, and are particularly useful for verifying EMI results in targeted locations.[39] Gypsum blocks, embedded in the soil, primarily monitor soil moisture through electrical resistance changes, with the gypsum material buffering against salinity effects to maintain measurement accuracy for water content, though high salinity can influence readings and requires calibration to account for such interferences.[40][41] Laboratory methods complement field data by providing standardized, precise quantification of soil salinity from collected samples. The saturated paste extract technique, the established standard for ECe (electrical conductivity of the saturation extract), involves mixing soil with water to form a paste, allowing salts to dissolve, then extracting and measuring the EC of the liquid phase, which directly reflects the salinity available to plant roots.[36] For quicker assessments, samples are oven-dried at 105°C to constant weight before preparing a 1:5 soil-to-water suspension, whose EC (EC1:5) serves as a proxy for salinity, often convertible to ECe via empirical factors like multiplication by 5-7 depending on soil texture.[36] Complementary metrics include pH, measured in the same extracts to assess alkalinity impacts on salt solubility, and the sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), calculated as SAR = [Na⁺] / √([Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺]/2) from cation concentrations in the extract, which indicates sodicity risk by evaluating sodium's dominance relative to divalent cations.[42] Best practices for accurate salinity assessment emphasize strategic sampling to capture vertical and temporal variability. Samples should be collected at multiple depths, such as 0-30 cm for surface-root zone effects and 30-60 cm for subsurface accumulation, using a soil auger to minimize contamination, with at least 10-15 subsamples composited per depth interval across uniform field zones.[43] Measurements are ideally conducted during dry periods, like late summer, when salts concentrate due to evapotranspiration, enhancing detection sensitivity. For EMI, site-specific calibration against lab ECe is crucial to account for clay content and moisture, ensuring reliable mapping that informs subsequent classification systems.[44]Soil Salinity Classification Systems

Soil salinity classification systems provide standardized frameworks for identifying and categorizing salt-affected soils based on measurable chemical properties, enabling consistent assessment across regions and supporting targeted management strategies. These systems primarily distinguish between saline, sodic, and saline-sodic soils using thresholds for electrical conductivity of the saturation extract (ECe) and exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP).[45][46] The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) system, established in the seminal 1954 handbook Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils, defines saline soils as those with ECe greater than 4 dS/m and ESP less than 15%, indicating high soluble salt content without significant sodium dominance. Sodic soils are characterized by ESP exceeding 15% and ECe less than 4 dS/m, often accompanied by a pH above 8.5 due to sodium's dispersive effects on soil structure. Saline-sodic soils meet both criteria (ECe > 4 dS/m and ESP > 15%), combining high salinity with sodium hazards.[45] This framework relies on laboratory-derived ECe from saturated paste extracts and ESP calculated as the proportion of sodium on the soil's cation exchange capacity (CEC). Soil texture indirectly influences classification by affecting CEC and water retention, with finer-textured soils (e.g., clays) exhibiting higher CEC and thus potentially lower ESP for equivalent sodium levels compared to sandy soils.[45][47] The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) adopts a similar diagnostic approach but emphasizes salinity degree classes for broader global application, as outlined in its 1988 guidelines on salt-affected soils. Saline soils under FAO criteria mirror USDA definitions (ECe > 4 dS/m, ESP < 15%, pH < 8.5), while sodic soils require ESP > 15%, pH > 8.5, and ECe < 4 dS/m; saline-sodic soils exceed both ECe and ESP thresholds. FAO further stratifies salinity intensity into classes: non-saline (ECe < 4 dS/m), slightly saline (4–8 dS/m), moderately saline (8–15 dS/m), and strongly saline (>15 dS/m), facilitating mapping and monitoring in diverse agroecological zones.[46] Like the USDA system, FAO indicators incorporate pH for sodicity confirmation and note texture's role in modulating salt distribution and hydraulic properties, though thresholds remain texture-independent.[46][48]| Classification Type | ECe (dS/m) | ESP (%) | pH | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USDA/FAO: Saline | >4 | <15 | <8.5 | High soluble salts; minimal sodium dispersion.[45][46] |

| USDA/FAO: Sodic | <4 | >15 | >8.5 | High exchangeable sodium; poor structure and infiltration.[45][46] |

| USDA/FAO: Saline-Sodic | >4 | >15 | Variable (often <8.5 initially) | Combined salinity and sodicity hazards.[45][46] |