Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solar irradiance

View on Wikipedia

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area (surface power density) received from the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of the measuring instrument. Solar irradiance is measured in watts per square metre (W/m2) in SI units.

Solar irradiance is often integrated over a given time period in order to report the radiant energy emitted into the surrounding environment (joule per square metre, J/m2) during that time period. This integrated solar irradiance is called solar irradiation, solar radiation, solar exposure, solar insolation, or insolation.

Irradiance may be measured in space or at the Earth's surface after atmospheric absorption and scattering. Irradiance in space is a function of distance from the Sun, the solar cycle, and cross-cycle changes.[2] Irradiance on the Earth's surface additionally depends on the tilt of the measuring surface, the height of the Sun above the horizon, and atmospheric conditions.[3] Solar irradiance affects plant metabolism and animal behavior.[4]

The study and measurement of solar irradiance has several important applications, including the prediction of energy generation from solar power plants, the heating and cooling loads of buildings, climate modeling and weather forecasting, passive daytime radiative cooling applications, and space travel.

Types

[edit]

There are several measured types of solar irradiance.

- Total solar irradiance (TSI) is a measure of the solar power over all wavelengths per unit area incident on the Earth's upper atmosphere. It is measured facing (pointing at / parallel to) the incoming sunlight (i.e. the flux through a surface perpendicular to the incoming sunlight; other angles would not be TSI).[3] The solar constant is a conventional measure of mean TSI at a distance of one astronomical unit (AU).

- Direct normal irradiance (DNI), or beam radiation, is measured perpendicularly to the Sun direction.[6] It excludes diffuse solar radiation (radiation that is scattered or reflected by atmospheric components).[6] Direct irradiance is equal to the extraterrestrial irradiance above the atmosphere minus the atmospheric losses due to absorption and scattering. Losses depend on time of day (length of light's path through the atmosphere depending on the solar elevation angle), cloud cover, moisture content and other contents. The irradiance above the atmosphere also varies with time of year (because the distance to the Sun varies), although this effect is generally less significant compared to the effect of losses on DNI.

- Direct horizontal irradiance (DirHI), or beam horizontal irradiance (BHI), is the direct component of irradiance received on a horizontal surface as opposed to a surface perpendicular to the direct sunlight.[7]

- Diffuse horizontal irradiance (DHI), or diffuse sky radiation, is the radiation at the Earth's surface from light scattered by the atmosphere. It is measured on a horizontal surface with radiation coming from all points in the sky excluding circumsolar radiation (radiation coming from the sun disk). There would be almost no DHI in the absence of atmosphere.[8]

- Global horizontal irradiance (GHI) is the total irradiance from the Sun on a horizontal surface on Earth. For instantaneous measurement, it is the sum of direct irradiance (after accounting for the solar zenith angle, , of the Sun) and diffuse horizontal irradiance:[8]

- Global tilted irradiance (GTI) is the total radiation received on a surface with defined tilt and azimuth, fixed or Sun-tracking. GTI can be measured[9] or modeled from GHI, DNI, DHI.[10][11][12] It is often a reference for photovoltaic power plants, while photovoltaic modules are mounted on the fixed or tracking constructions.

- Global normal irradiance (GNI) is the total irradiance from the Sun at the surface of Earth at a given location with a surface element perpendicular to the Sun.

Spectral versions of the above irradiances (e.g. spectral TSI, spectral DNI, etc.) are any of the above with units divided either by meter or nanometer (for a spectral graph as function of wavelength), or per-Hz (for a spectral function with an x-axis of frequency).[citation needed] When one plots such spectral distributions as a graph, the integral of the function (area under the curve) will be the (non-spectral) irradiance. e.g.: Say one had a solar cell on the surface of the earth facing straight up, and had DNI in units of Wm−2nm−1, graphed as a function of wavelength (in nm). Then, the unit of the integral (Wm−2) is the product of those two units.[citation needed]

Units

[edit]The SI unit of irradiance is watts per square metre (W/m2 = Wm−2). The unit of insolation often used in the solar power industry is kilowatt hours per square metre (kWh/m2).[13]

The langley is an alternative unit of insolation. One langley is one thermochemical calorie per square centimetre or 41,840 J/m2.[14]

At the top of Earth's atmosphere

[edit]

The average annual solar radiation arriving at the top of the Earth's atmosphere is about 1361 W/m2. This represents the power per unit area of solar irradiance across the spherical surface surrounding the Sun with a radius equal to the distance to the Earth (1 AU). This means that the approximately circular disc of the Earth, as viewed from the Sun, receives a roughly stable 1361 W/m2 at all times. The area of this circular disc is πr2, in which r is the radius of the Earth. Because the Earth is approximately spherical, it has total area , meaning that the solar radiation arriving at the top of the atmosphere, averaged over the entire surface of the Earth, is simply divided by four to get 340 W/m2. In other words, averaged over the year and the day, the Earth's atmosphere receives 340 W/m2 from the Sun. This figure is important in radiative forcing.

Derivation

[edit]The distribution of solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere is determined by Earth's sphericity and orbital parameters. This applies to any unidirectional beam incident to a rotating sphere. Insolation is essential for numerical weather prediction and understanding seasons and climatic change. Application to ice ages is known as Milankovitch cycles.

Distribution is based on a fundamental identity from spherical trigonometry, the spherical law of cosines: where a, b and c are arc lengths, in radians, of the sides of a spherical triangle. C is the angle in the vertex opposite the side which has arc length c. Applied to the calculation of solar zenith angle Θ, the following applies to the spherical law of cosines:

This equation can be also derived from a more general formula:[15] where β is an angle from the horizontal and γ is the solar azimuth angle.

The derivation of the cosine of solar zenith angle, , based on vector analysis instead of spherical trigonometry is also available in the article about solar azimuth angle.

The separation of Earth from the Sun can be denoted RE and the mean distance can be denoted R0, approximately 1 astronomical unit (AU). The solar constant is denoted S0. The solar flux density (insolation) onto a plane tangent to the sphere of the Earth, but above the bulk of the atmosphere (elevation 100 km or greater) is:

The average of Q over a day is the average of Q over one rotation, or the hour angle progressing from h = π to h = −π:

Let h0 be the hour angle when Q becomes positive. This could occur at sunrise when , or for h0 as a solution of or

If tan(φ) tan(δ) > 1, then the sun does not set and the sun is already risen at h = π, so ho = π. If tan(φ) tan(δ) < −1, the sun does not rise and .

is nearly constant over the course of a day, and can be taken outside the integral

Therefore:

Let θ be the conventional polar angle describing a planetary orbit. Let θ = 0 at the March equinox. The declination δ as a function of orbital position is[16][17] where ε is the obliquity. (Note: The correct formula, valid for any axial tilt, is .[18]) The conventional longitude of perihelion ϖ is defined relative to the March equinox, so for the elliptical orbit:[19] or

With knowledge of ϖ, ε and e from astrodynamical calculations[20] and So from a consensus of observations or theory, can be calculated for any latitude φ and θ. Because of the elliptical orbit, and as a consequence of Kepler's second law, θ does not progress uniformly with time. Nevertheless, θ = 0° is exactly the time of the March equinox, θ = 90° is exactly the time of the June solstice, θ = 180° is exactly the time of the September equinox and θ = 270° is exactly the time of the December solstice.

A simplified equation for irradiance on a given day is:[21][22]

where n is a number of a day of the year.

Variation

[edit]Total solar irradiance (TSI)[23] changes slowly on decadal and longer timescales. The variation during solar cycle 21 was about 0.1% (peak-to-peak).[24] In contrast to older reconstructions,[25] most recent TSI reconstructions point to an increase of only about 0.05% to 0.1% between the 17th century Maunder Minimum and the present.[26][27][28] However, current understanding based on various lines of evidence suggests that the lower values for the secular trend are more probable.[28] In particular, a secular trend greater than 2 Wm−2 is considered highly unlikely.[28][29][30] Ultraviolet irradiance (EUV) varies by approximately 1.5 percent from solar maxima to minima, for 200 to 300 nm wavelengths.[31] However, a proxy study estimated that UV has increased by 3.0% since the Maunder Minimum.[32]

Some variations in insolation are not due to solar changes but rather due to the Earth moving between its perihelion and aphelion, or changes in the latitudinal distribution of radiation. These orbital changes or Milankovitch cycles have caused radiance variations of as much as 25% (locally; global average changes are much smaller) over long periods. The most recent significant event was an axial tilt of 24° during boreal summer near the Holocene climatic optimum. Obtaining a time series for a for a particular time of year, and particular latitude, is a useful application in the theory of Milankovitch cycles. For example, at the summer solstice, the declination δ is equal to the obliquity ε. The distance from the Sun is

For this summer solstice calculation, the role of the elliptical orbit is entirely contained within the important product , the precession index, whose variation dominates the variations in insolation at 65° N when eccentricity is large. For the next 100,000 years, with variations in eccentricity being relatively small, variations in obliquity dominate.

Measurement

[edit]The space-based TSI record comprises measurements from more than ten radiometers and spans three solar cycles. All modern TSI satellite instruments employ active cavity electrical substitution radiometry. This technique measures the electrical heating needed to maintain an absorptive blackened cavity in thermal equilibrium with the incident sunlight which passes through a precision aperture of calibrated area. The aperture is modulated via a shutter. Accuracy uncertainties of < 0.01% are required to detect long term solar irradiance variations, because expected changes are in the range 0.05–0.15 W/m2 per century.[33]

Intertemporal calibration

[edit]In orbit, radiometric calibrations drift for reasons including solar degradation of the cavity, electronic degradation of the heater, surface degradation of the precision aperture and varying surface emissions and temperatures that alter thermal backgrounds. These calibrations require compensation to preserve consistent measurements.[33]

For various reasons, the sources do not always agree. The Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment/Total Irradiance Measurement (SORCE/TIM) TSI values are lower than prior measurements by the Earth Radiometer Budget Experiment (ERBE) on the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS), VIRGO on the Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SoHO) and the ACRIM instruments on the Solar Maximum Mission (SMM), Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) and ACRIMSAT. Pre-launch ground calibrations relied on component rather than system-level measurements since irradiance standards at the time lacked sufficient absolute accuracies.[33]

Measurement stability involves exposing different radiometer cavities to different accumulations of solar radiation to quantify exposure-dependent degradation effects. These effects are then compensated for in the final data. Observation overlaps permits corrections for both absolute offsets and validation of instrumental drifts.[33]

Uncertainties of individual observations exceed irradiance variability (~0.1%). Thus, instrument stability and measurement continuity are relied upon to compute real variations.

Long-term radiometer drifts can potentially be mistaken for irradiance variations which can be misinterpreted as affecting climate. Examples include the issue of the irradiance increase between cycle minima in 1986 and 1996, evident only in the ACRIM composite (and not the model) and the low irradiance levels in the PMOD composite during the 2008 minimum.

Despite the fact that ACRIM I, ACRIM II, ACRIM III, VIRGO and TIM all track degradation with redundant cavities, notable and unexplained differences remain in irradiance and the modeled influences of sunspots and faculae.

Persistent inconsistencies

[edit]Disagreement among overlapping observations indicates unresolved drifts that suggest the TSI record is not sufficiently stable to discern solar changes on decadal time scales. Only the ACRIM composite shows irradiance increasing by ~1 W/m2 between 1986 and 1996. It is noteworthy that the most accurate TSI reconstructions with empirical and physics-based semi-empirical models using independent inputs consistently disfavor this increase during the ACRIM-gap.[33][34][35][36][37]

Recommendations to resolve the instrument discrepancies include validating optical measurement accuracy by comparing ground-based instruments to laboratory references, such as those at National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST); NIST validation of aperture area calibrations uses spares from each instrument; and applying diffraction corrections from the view-limiting aperture.[33]

For ACRIM, NIST determined that diffraction from the view-limiting aperture contributes a 0.13% signal not accounted for in the three ACRIM instruments. This correction lowers the reported ACRIM values, bringing ACRIM closer to TIM. In ACRIM and all other instruments but TIM, the aperture is deep inside the instrument, with a larger view-limiting aperture at the front. Depending on edge imperfections this can directly scatter light into the cavity. This design admits into the front part of the instrument two to three times the amount of light intended to be measured; if not completely absorbed or scattered, this additional light produces erroneously high signals. In contrast, TIM's design places the precision aperture at the front so that only desired light enters.[33]

Variations from other sources likely include an annual systematics in the ACRIM III data that is nearly in phase with the Sun-Earth distance and 90-day spikes in the VIRGO data coincident with SoHO spacecraft maneuvers that were most apparent during the 2008 solar minimum.

TSI Radiometer Facility

[edit]TIM's high absolute accuracy creates new opportunities for measuring climate variables. TSI Radiometer Facility (TRF) is a cryogenic radiometer that operates in a vacuum with controlled light sources. L-1 Standards and Technology (LASP) designed and built the system, completed in 2008. It was calibrated for optical power against the NIST Primary Optical Watt Radiometer, a cryogenic radiometer that maintains the NIST radiant power scale to an uncertainty of 0.02% (1σ). As of 2011 TRF was the only facility that approached the desired <0.01% uncertainty for pre-launch validation of solar radiometers measuring irradiance (rather than merely optical power) at solar power levels and under vacuum conditions.[33]

TRF encloses both the reference radiometer and the instrument under test in a common vacuum system that contains a stationary, spatially uniform illuminating beam. A precision aperture with an area calibrated to 0.0031% (1σ) determines the beam's measured portion. The test instrument's precision aperture is positioned in the same location, without optically altering the beam, for direct comparison to the reference. Variable beam power provides linearity diagnostics, and variable beam diameter diagnoses scattering from different instrument components.[33]

The Glory/TIM and PICARD/PREMOS flight instrument absolute scales are now traceable to the TRF in both optical power and irradiance. The resulting high accuracy reduces the consequences of any future gap in the solar irradiance record.[33]

| Instrument | Irradiance, view-limiting aperture overfilled |

Irradiance, precision aperture overfilled |

Difference attributable to scatter error |

Measured optical power error |

Residual irradiance agreement |

Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORCE/TIM ground | — | −0.037% | — | −0.037% | 0.000% | 0.032% |

| Glory/TIM flight | — | −0.012% | — | −0.029% | 0.017% | 0.020% |

| PREMOS-1 ground | −0.005% | −0.104% | 0.098% | −0.049% | −0.104% | ~0.038% |

| PREMOS-3 flight | 0.642% | 0.605% | 0.037% | 0.631% | −0.026% | ~0.027% |

| VIRGO-2 ground | 0.897% | 0.743% | 0.154% | 0.730% | 0.013% | ~0.025% |

2011 reassessment

[edit]The most probable value of TSI representative of solar minimum is 1360.9±0.5 W/m2, lower than the earlier accepted value of 1365.4±1.3 W/m2, established in the 1990s. The new value came from SORCE/TIM and radiometric laboratory tests. Scattered light is a primary cause of the higher irradiance values measured by earlier satellites in which the precision aperture is located behind a larger, view-limiting aperture. The TIM uses a view-limiting aperture that is smaller than the precision aperture that precludes this spurious signal. The new estimate is from better measurement rather than a change in solar output.[33]

A regression model-based split of the relative proportion of sunspot and facular influences from SORCE/TIM data accounts for 92% of observed variance and tracks the observed trends to within TIM's stability band. This agreement provides further evidence that TSI variations are primarily due to solar surface magnetic activity.[33]

Instrument inaccuracies add a significant uncertainty in determining Earth's energy balance. The energy imbalance has been variously measured (during a deep solar minimum of 2005–2010) to be +0.58±0.15 W/m2,[38] +0.60±0.17 W/m2[39] and +0.85 W/m2. Estimates from space-based measurements range +3–7 W/m2. SORCE/TIM's lower TSI value reduces this discrepancy by 1 W/m2. This difference between the new lower TIM value and earlier TSI measurements corresponds to a climate forcing of −0.8 W/m2, which is comparable to the energy imbalance.[33]

On Earth's surface

[edit]

Average annual solar radiation arriving at the top of the Earth's atmosphere is roughly 1361 W/m2.[40] The Sun's rays are attenuated as they pass through the atmosphere, leaving maximum normal surface irradiance at approximately 1000 W/m2 at sea level on a clear day. When 1361 W/m2 is arriving above the atmosphere (when the Sun is at the zenith in a cloudless sky), direct sun is about 1050 W/m2, and global radiation on a horizontal surface at ground level is about 1120 W/m2.[41] The latter figure includes radiation scattered or reemitted by the atmosphere and surroundings. The actual figure varies with the Sun's angle and atmospheric circumstances. Ignoring clouds, the daily average insolation for the Earth is approximately 6 kWh/m2 = 21.6 MJ/m2.

The output of, for example, a photovoltaic panel, partly depends on the angle of the sun relative to the panel. One Sun is a unit of power flux, not a standard value for actual insolation. Sometimes this unit is referred to as a Sol, not to be confused with a sol, meaning one solar day.[42]

Absorption and reflection

[edit]

Part of the radiation reaching an object is absorbed and the remainder reflected. Usually, the absorbed radiation is converted to thermal energy, increasing the object's temperature. Humanmade or natural systems, however, can convert part of the absorbed radiation into another form such as electricity or chemical bonds, as in the case of photovoltaic cells or plants. The proportion of reflected radiation is the object's reflectivity or albedo.

Projection effect

[edit]

Insolation onto a surface is largest when the surface directly faces (is normal to) the sun. As the angle between the surface and the Sun moves from normal, the insolation is reduced in proportion to the angle's cosine; see effect of Sun angle on climate.

In the figure, the angle shown is between the ground and the sunbeam rather than between the vertical direction and the sunbeam; hence the sine rather than the cosine is appropriate. A sunbeam one mile wide arrives from directly overhead, and another at a 30° angle to the horizontal. The sine of a 30° angle is 1/2, whereas the sine of a 90° angle is 1. Therefore, the angled sunbeam spreads the light over twice the area. Consequently, half as much light falls on each square mile.

This projection effect is the main reason why Earth's polar regions are much colder than equatorial regions. On an annual average, the poles receive less insolation than does the equator, because the poles are always angled more away from the Sun than the tropics, and moreover receive no insolation at all for the six months of their respective winters.

Absorption effect

[edit]At a lower angle, the light must also travel through more atmosphere. This attenuates it (by absorption and scattering) further reducing insolation at the surface.

Attenuation is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law, namely that the transmittance or fraction of insolation reaching the surface decreases exponentially in the optical depth or absorbance (the two notions differing only by a constant factor of ln(10) = 2.303) of the path of insolation through the atmosphere. For any given short length of the path, the optical depth is proportional to the number of absorbers and scatterers along that length, typically increasing with decreasing altitude. The optical depth of the whole path is then the integral (sum) of those optical depths along the path.

When the density of absorbers is layered, that is, depends much more on vertical than horizontal position in the atmosphere, to a good approximation the optical depth is inversely proportional to the projection effect, that is, to the cosine of the zenith angle. Since transmittance decreases exponentially with increasing optical depth, as the sun approaches the horizon there comes a point when absorption dominates projection for the rest of the day. With a relatively high level of absorbers this can be a considerable portion of the late afternoon, and likewise of the early morning. Conversely, in the (hypothetical) total absence of absorption, the optical depth remains zero at all altitudes of the sun, that is, transmittance remains 1, and so only the projection effect applies.

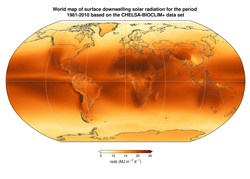

Solar potential maps

[edit]Assessment and mapping of solar potential at the global, regional and country levels have been the subject of significant academic and commercial interest. One of the earliest attempts to carry out comprehensive mapping of solar potential for individual countries was the Solar & Wind Resource Assessment (SWERA) project,[43] funded by the United Nations Environment Program and carried out by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) provides data for global solar potential maps through the CERES experiment and the POWER project. Global mapping by many other similar institutes are available on the Global Atlas for Renewable Energy provided by the International Renewable Energy Agency. A number of commercial firms now exist to provide solar resource data to solar power developers, including 3E, Clean Power Research, SoDa Solar Radiation Data, Solargis, Vaisala (previously 3Tier), and Vortex, and these firms have often provided solar potential maps for free. The Global Solar Atlas was launched by the World Bank in January 2017, using data provided by Solargis, to provide a single source for high-quality solar data, maps, and GIS layers covering all countries.

- Maps of GHI potential by region and country (Note: colors are not consistent across maps)

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

-

Latin America and Caribbean

-

China

-

India

-

Mexico

-

South Africa

Solar radiation maps are built using databases derived from satellite imagery, as for example using visible images from Meteosat Prime satellite. A method is applied to the images to determine solar radiation. One well validated satellite-to-irradiance model is the SUNY model.[44] The accuracy of this model is well evaluated. In general, solar irradiance maps are accurate, especially for Global Horizontal Irradiance.

Applications

[edit]Solar power

[edit]

Solar irradiation figures are used to plan the deployment of solar power systems.[45] In many countries, the figures can be obtained from an insolation map or from insolation tables that reflect data over the prior 30–50 years. Different solar power technologies are able to use different components of the total irradiation. While solar photovoltaics panels are able to convert to electricity both direct irradiation and diffuse irradiation, concentrated solar power is only able to operate efficiently with direct irradiation, thus making these systems suitable only in locations with relatively low cloud cover.

Because solar collectors panels are almost always mounted at an angle towards the Sun, insolation figures must be adjusted to find the amount of sunlight falling on the panel. This will prevent estimates that are inaccurately low for winter and inaccurately high for summer.[46] This also means that the amount of sunlight falling on a solar panel at high latitude is not as low compared to one at the equator as would appear from just considering insolation on a horizontal surface. Horizontal insolation values range from 800 to 950 kWh/(kWp·y) in Norway to up to 2,900 kWh/(kWp·y) in Australia. But a properly tilted panel at 50° latitude receives 1860 kWh/m2/y, compared to 2370 at the equator.[47] In fact, under clear skies a solar panel placed horizontally at the north or south pole at midsummer receives more sunlight over 24 hours (cosine of angle of incidence equal to sin(23.5°) or about 0.40) than a horizontal panel at the equator at the equinox (average cosine equal to 1/π or about 0.32).

Photovoltaic panels are rated under standard conditions to determine the Wp (peak watts) rating,[48] which can then be used with insolation, adjusted by factors such as tilt, tracking and shading, to determine the expected output.[49]

Buildings

[edit]

In construction, insolation is an important consideration when designing a building for a particular site.[50]

The projection effect can be used to design buildings that are cool in summer and warm in winter, by providing vertical windows on the equator-facing side of the building (the south face in the Northern Hemisphere, or the north face in the Southern Hemisphere): this maximizes insolation in the winter months when the Sun is low in the sky and minimizes it in the summer when the Sun is high. (The Sun's north–south path through the sky spans 47° through the year).

Civil engineering

[edit]In civil engineering and hydrology, numerical models of snowmelt runoff use observations of insolation. This permits estimation of the rate at which water is released from a melting snowpack. Field measurement is accomplished using a pyranometer.

Climate research

[edit]Irradiance plays a part in climate modeling and weather forecasting. A non-zero average global net radiation at the top of the atmosphere is indicative of Earth's thermal disequilibrium as imposed by climate forcing.

The impact of the lower 2014 TSI value on climate models is unknown. A few tenths of a percent change in the absolute TSI level is typically considered to be of minimal consequence for climate simulations. The new measurements require climate model parameter adjustments.

Experiments with GISS Model 3 investigated the sensitivity of model performance to the TSI absolute value during the present and pre-industrial epochs, and describe, for example, how the irradiance reduction is partitioned between the atmosphere and surface and the effects on outgoing radiation.[33]

Assessing the impact of long-term irradiance changes on climate requires greater instrument stability[33] combined with reliable global surface temperature observations to quantify climate response processes to radiative forcing on decadal time scales. The observed 0.1% irradiance increase imparts 0.22 W/m2 climate forcing, which suggests a transient climate response of 0.6 °C per W/m2. This response is larger by a factor of 2 or more than in the IPCC-assessed 2008 models, possibly appearing in the models' heat uptake by the ocean.[33]

Global cooling

[edit]Measuring a surface's capacity to reflect solar irradiance is essential to passive daytime radiative cooling, which has been proposed as a method of reversing local and global temperature increases associated with global warming.[51][52] In order to measure the cooling power of a passive radiative cooling surface, both the absorbed powers of atmospheric and solar radiations must be quantified. On a clear day, solar irradiance can reach 1000 W/m2 with a diffuse component between 50 and 100 W/m2. On average the cooling power of a passive daytime radiative cooling surface has been estimated at ~100-150 W/m2.[53]

Space

[edit]Insolation is the primary variable affecting equilibrium temperature in spacecraft design and planetology.

Solar activity and irradiance measurement is a concern for space travel. For example, the American space agency, NASA, launched its Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) satellite with Solar Irradiance Monitors.[2]

See also

[edit]- Earth's energy budget

- PI curve (photosynthesis-irradiance curve)

- Irradiance

- Albedo

- Flux

- Power density

- Sun chart

- Sunlight

- Sunshine duration

References

[edit]- ^ Brun, P.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Hari, C.; Pellissier, L.; Karger, D.N. "Global climate-related predictors at kilometre resolution for the past and future". Earth Syst. Sci. Data. doi:10.5194/essd-2022-212.

- ^ a b Michael Boxwell, Solar Electricity Handbook: A Simple, Practical Guide to Solar Energy (2012), pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Stickler, Greg. "Educational Brief - Solar Radiation and the Earth System". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Abiotic factor. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds Emily Monosson and C. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington, DC

- ^ a b World Bank (2017). Global Solar Atlas.

- ^ a b Kirk, Alexander P. (2015). Solar Photovoltaic Cells Photons to Electricity. Elsevier. pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-0-12-802329-7.

- ^ Zhang, T., Stackhouse Jr., P.W., Macpherson, B., and Mikovitz, J.C., 2024. A CERES-based dataset of hourly DNI, DHI and global tilted irradiance (GTI) on equatorward tilted surfaces: Derivation and comparison with the ground-based BSRN data. Sol. Energy, 274 (2024) 112538. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2024.112538.

- ^ a b "Solar Resource Glossary". National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ "What is the Difference between Horizontal and Tilted Global Solar Irradiance?". Kipp & Zonen. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Gueymard, Christian A. (March 2009). "Direct and indirect uncertainties in the prediction of tilted irradiance for solar engineering applications". Solar Energy. 83 (3): 432–444. Bibcode:2009SoEn...83..432G. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2008.11.004.

- ^ Sengupta, Manajit; Habte, Aron; Gueymard, Christian; Wilbert, Stefan; Renné, Dave; Stoffel, Thomas (1 December 2017). "Best Practices Handbook for the Collection and Use of Solar Resource Data for Solar Energy Applications: Second Edition". National Renewable Energy Laboratory: NREL/TP–5D00–68886, 1411856. doi:10.2172/1411856. OSTI 1411856.

- ^ Gueymard, Chris A. (2015). "Uncertainties in Transposition and Decomposition Models: Lesson Learned" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Solar Radiation Basics". U. S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Ambler; Taylor, Barry N. (17 February 2022). "NIST Guide to the SI, Appendix B.8: Factors for Units Listed Alphabetically". SP 811 - The NIST Guide for the use of International System of Units (Report). National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- ^ "Part 3: Calculating Solar Angles - ITACA". www.itacanet.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Insolation in The Azimuth Project". www.azimuthproject.org. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Declination Angle - PVEducation". www.pveducation.org. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Van Brummelen, Glen (2012). Heavenly Mathematics: The Forgotten Art of Spherical Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. Bibcode:2012hmfa.book.....V.

- ^ Berger, AndréL (1 December 1978). "Long-Term Variations of Daily Insolation and Quaternary Climatic Changes". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 35 (12): 2362–2367. Bibcode:1978JAtS...35.2362B. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1978)035<2362:LTVODI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-4928.

- ^ "Determination of the Earth's Orbital Parameters". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ^ Duffie, John A.; Beckman, William A. (10 April 2013). Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes: Duffie/Solar Engineering 4e. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118671603. ISBN 978-1-118-67160-3.

- ^ "Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes" (PDF).

- ^ Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment, Total Solar Irradiance Data (retrieved 16 July 2015)

- ^ Willson, Richard C.; Hudson, H. S. (1991). "The Sun's luminosity over a complete solar cycle". Nature. 351 (6321): 42–4. Bibcode:1991Natur.351...42W. doi:10.1038/351042a0. S2CID 4273483.

- ^ Solar Influences on Global Change. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. 1994. p. 36. Bibcode:1994nap..book.4778N. doi:10.17226/4778. hdl:2060/19950005971. ISBN 978-0-309-05148-4.

- ^ Wang, Y. M.; Lean, J. L.; Sheeley, N. R. (2005). "Modeling the Sun's magnetic field and irradiance since 1713" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 625 (1): 522–38. Bibcode:2005ApJ...625..522W. doi:10.1086/429689. S2CID 20573668. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012.

- ^ Krivova, N. A.; Balmaceda, L.; Solanki, S. K. (2007). "Reconstruction of solar total irradiance since 1700 from the surface magnetic flux". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 467 (1): 335–46. Bibcode:2007A&A...467..335K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066725.

- ^ a b c Chatzistergos, Theodosios; Krivova, N. A.; Yeo, K. L. (2023). "Long-term changes in solar activity and irradiance". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. 252 106150. arXiv:2303.03046. Bibcode:2023JASTP.25206150C. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2023.106150.

- ^ Yeo, K. L.; Solanki, S. K.; Krivova, N. A.; Rempel, M.; Anusha, L. S.; Shapiro, A. I.; Tagirov, R. V.; Witzke, V. (16 October 2020). "The Dimmest State of the Sun". Geophysical Research Letters. 47 (19) e2020GL090243. arXiv:2102.09487. Bibcode:2020GeoRL..4790243Y. doi:10.1029/2020GL090243. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ Lockwood, Mike; Ball, William T. (2020). "Placing limits on long-term variations in quiet-Sun irradiance and their contribution to total solar irradiance and solar radiative forcing of climate". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 476 (2238) 20200077. Bibcode:2020RSPSA.47600077L. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0077. ISSN 1364-5021. PMC 7428030. PMID 32831591.

- ^ Lean, J. (14 April 1989). "Contribution of Ultraviolet Irradiance Variations to Changes in the Sun's Total Irradiance". Science. 244 (4901): 197–200. Bibcode:1989Sci...244..197L. doi:10.1126/science.244.4901.197. PMID 17835351. S2CID 41756073.

1 percent of the sun's energy is emitted at ultraviolet wavelengths between 200 and 300 nanometers, the decrease in this radiation from 1 July 1981 to 30 June 1985 accounted for 19 percent of the decrease in the total irradiance

(19% of the 1/1366 total decrease is 1.4% decrease in UV) - ^ Fligge, M.; Solanki, S. K. (2000). "The solar spectral irradiance since 1700". Geophysical Research Letters. 27 (14): 2157–2160. Bibcode:2000GeoRL..27.2157F. doi:10.1029/2000GL000067. S2CID 54744463.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kopp, Greg; Lean, Judith L. (14 January 2011). "A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance". Geophysical Research Letters. 38 (1): L01706. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..38.1706K. doi:10.1029/2010GL045777.

- ^ Krivova NA, Solanki SK, Wenzler T (1 October 2009). "ACRIM-gap and total solar irradiance revisited: Is there a secular trend between 1986 and 1996?". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (20) 2009GL040707: L20101. arXiv:0911.3817. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3620101K. doi:10.1029/2009GL040707.

- ^ Amdur, T.; Huybers, P. (16 August 2023). "A Bayesian Model for Inferring Total Solar Irradiance From Proxies and Direct Observations: Application to the ACRIM Gap". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 128 (15) e2023JD038941. Bibcode:2023JGRD..12838941A. doi:10.1029/2023JD038941. ISSN 2169-897X. S2CID 260264050.

- ^ Chatzistergos, Theodosios; Krivova, Natalie A.; Yeo, Kok Leng (2023). "Long-term changes in solar activity and irradiance". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. 252 106150. arXiv:2303.03046. Bibcode:2023JASTP.25206150C. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2023.106150.

- ^ Chatzistergos, Theodosios; Krivova, Natalie A.; Solanki, Sami K.; Leng Yeo, Kok (2025). "Revisiting the SATIRE-S irradiance reconstruction: Heritage of Mt Wilson magnetograms and Ca II K observations". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 696: A204. arXiv:2503.15903. Bibcode:2025A&A...696A.204C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202554044. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Hansen, James; Sato, Makiko; Kharecha, Pushker; von Schuckmann, Karina (January 2012). "Earth's Energy Imbalance". Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

- ^ Stephens, Graeme L.; Li, Juilin; Wild, Martin; Clayson, Carol Anne; Loeb, Norman; Kato, Seiji; L'Ecuyer, Tristan; Jr, Paul W. Stackhouse; Lebsock, Matthew (1 October 2012). "An update on Earth's energy balance in light of the latest global observations". Nature Geoscience. 5 (10): 691–696. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..691S. doi:10.1038/ngeo1580. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Coddington, O.; Lean, J. L.; Pilewskie, P.; Snow, M.; Lindholm, D. (22 August 2016). "A Solar Irradiance Climate Data Record". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 97 (7): 1265–1282. Bibcode:2016BAMS...97.1265C. doi:10.1175/bams-d-14-00265.1.

- ^ "Introduction to Solar Radiation". Newport Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Allison, Michael; Schmunk, Robert (5 August 2008). "Technical Notes on Mars Solar Time". NASA. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Solar and Wind Energy Resource Assessment (SWERA) | Open Energy Information".

- ^ Nonnenmacher, Lukas; Kaur, Amanpreet; Coimbra, Carlos F.M. (1 January 2014). "Verification of the SUNY direct normal irradiance model with ground measurements". Solar Energy. 99: 246–258. Bibcode:2014SoEn...99..246N. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2013.11.010. ISSN 0038-092X.

- ^ "Determining your solar power requirements and planning the number of components".

- ^ "Heliostat Concepts". redrok.com.

- ^ Converted to yearly basis from Landau, Charles R. (2017). "Optimum Tilt of Solar Panels".

- ^ [1] Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How Do Solar Panels Work?". glrea.org. Archived from the original on 15 October 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Nall, D. H. "Looking across the water: Climate-adaptive buildings in the United States & Europe" (PDF). The Construction Specifier. 57 (2004–11): 50–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009.

- ^ Han, Di; Fei, Jipeng; Li, Hong; Ng, Bing Feng (August 2022). "The criteria to achieving sub-ambient radiative cooling and its limits in tropical daytime". Building and Environment. 221 (1) 109281. Bibcode:2022BuEnv.22109281H. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109281. hdl:10356/163060 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Munday, Jeremy (2019). "Tackling Climate Change through Radiative Cooling". Joule. 3 (9): 2057–2060. Bibcode:2019Joule...3.2057M. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.07.010. S2CID 201590290.

- ^ Chen, Meijie; Pang, Dan; Chen, Xingyu; Yan, Hongjie; Yang, Yuan (2022). "Passive daytime radiative cooling: Fundamentals, material designs, and applications". EcoMat. 4 e12153. doi:10.1002/eom2.12153. S2CID 240331557.

Bibliography

[edit]- Willson, Richard C.; Hudson, H. S. (1991). "The Sun's luminosity over a complete solar cycle". Nature. 351 (6321): 42–4. Bibcode:1991Natur.351...42W. doi:10.1038/351042a0. S2CID 4273483.

- "The Sun and Climate". U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 0095-00. Retrieved 21 February 2005.

- Foukal, Peter; et al. (1977). "The effects of sunspots and faculae on the solar constant". Astrophysical Journal. 215: 952. Bibcode:1977ApJ...215..952F. doi:10.1086/155431.

- Stetson, H.T. (1937). Sunspots and Their Effects. New York: McGraw Hill. Bibcode:1937sate.book.....S.

- Yaskell, Steven Haywood (31 December 2012). Grand Phases On The Sun: The case for a mechanism responsible for extended solar minima and maxima. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-6300-9.

External links

[edit]- Global Solar Atlas - browse or download maps and GIS data layers (global or per country) of the long-term averages of solar irradiation data (published by the World Bank, provided by Solargis)]

- Solcast - solar irradiance data updated every 10–15 minutes. Recent, live, historical and forecast, free for public research use

- Recent Total Solar Irradiance data Archived 6 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine updated every Monday

- San Francisco Solar Map

- European Commission- Interactive Maps

- Yesterday's Australian Solar Radiation Map

- Solar Radiation using Google Maps Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- SMARTS, software to compute solar insolation of each date/location of earth Solar Resource Data and Tools

- NASA Surface meteorology and Solar Energy

- insol: R package for insolation on complex terrain

- Online insolation calculator

Solar irradiance

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Types

Solar irradiance is the radiant flux density of electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun incident on a given surface, expressed in watts per square meter (W/m²).[8] It measures the instantaneous power delivered by solar radiation per unit area, encompassing the full spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths.[9] This quantity arises from the Sun's thermonuclear fusion processes, where energy is transported outward through radiative and convective zones before escaping as photons.[10] At Earth's surface, solar irradiance is categorized into direct beam, diffuse, and total (global) components based on atmospheric interactions. Direct normal irradiance (DNI) quantifies the unscattered solar radiation received on a surface perpendicular to the Sun's rays, excluding effects from clouds or aerosols in clear-sky conditions; typical peak values reach about 1000 W/m² under optimal circumstances. Diffuse horizontal irradiance (DHI) represents the omnidirectional scattered radiation intercepted by a horizontal surface, primarily due to molecular scattering (Rayleigh), aerosol interactions, and cloud reflections.[11] Global horizontal irradiance (GHI), the sum of these, is the total solar radiation on a horizontal plane and is calculated as GHI = DHI + DNI × cos(θ_z), where θ_z is the solar zenith angle.[11] [12] These types reflect causal pathways: direct irradiance follows a straight-line propagation attenuated by absorption and scattering, while diffuse components result from angular redistribution of photons via atmospheric particles, influencing applications such as photovoltaic efficiency where DNI dominates concentrating systems and GHI informs flat-plate designs.[13] Extraterrestrial solar irradiance, unmodified by Earth's atmosphere, averages approximately 1366 W/m² at 1 astronomical unit but is addressed separately from surface classifications.[8]Units and Standards

Solar irradiance is measured in the International System of Units (SI) as watts per square meter (W/m²), denoting the power received per unit area perpendicular to the incoming radiation.[14][15] This unit applies to instantaneous measurements of power density, distinguishing irradiance from integrated quantities like insolation, which accumulate energy over time in units such as megajoules per square meter (MJ/m²) or watt-hours per square meter (Wh/m²).[9] International standards govern the classification and calibration of instruments for solar irradiance measurement, ensuring traceability and accuracy. The ISO 9060:2018 standard specifies requirements for pyranometers (measuring hemispherical radiation) and pyrheliometers (measuring direct beam radiation), classifying them into performance categories—A (highest accuracy), B, and C—based on response time, thermal offset, and directional response errors determined through indoor and outdoor testing.[16][17] Calibration against the World Radiometric Reference (WRR), maintained by the Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos/World Radiation Center (PMOD/WRC), provides the absolute scale, with the WRR defined by a group of six absolute cavity pyrheliometers since 1977 and validated to within 0.3% of cryogenic radiometer measurements.[18] Reference spectra standardize spectral distributions for testing and modeling. The ASTM G173-03(2020) provides tables for direct normal and hemispherical spectral irradiance under air mass 1.5 global (AM1.5G) conditions on a 37° tilted surface, representing mid-latitude summer midday averages with 1000 W/m² total irradiance.[19] For extraterrestrial irradiance, ASTM E490-00a defines the zero air mass (AM0) spectrum at 1366.1 W/m² total, derived from satellite and high-altitude observations.[20] These standards facilitate consistent comparisons in photovoltaic performance and atmospheric studies, with NREL contributing to their development through empirical validation.[17]Extraterrestrial Solar Irradiance

Average Value and Theoretical Derivation

The average extraterrestrial solar irradiance, commonly termed the solar constant, is 1361 W/m², representing the total solar power incident per unit area perpendicular to the Sun's rays at Earth's mean orbital distance of one astronomical unit (AU).[4] This value is derived from space-based radiometric measurements, with the Total and Spectral Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1) on the International Space Station yielding 1361.6 ± 0.3 W/m² during the 2019 solar minimum, confirming a downward revision from earlier estimates of 1366–1367 W/m² based on pre-2003 satellite data.[4] [21] Theoretically, this average value emerges from the Sun's total bolometric luminosity , which is W, divided by the surface area of a sphere with radius equal to 1 AU ( m): . This yields approximately 1361 W/m², assuming isotropic emission and neglecting minor orbital eccentricity, which introduces a seasonal variation of about ±3.3% but averages to the mean over an orbital period.[22] The formula accounts for the geometric dilution of the Sun's output, treating it as a point source radiating uniformly across the sphere enclosing Earth at mean distance, with the factor of 4π arising from the solid angle subtended by the full sky.[23] To incorporate elliptical orbit effects, the instantaneous irradiance approximates , where is the annual mean (1361 W/m²) and is the day of the year; time-averaging over 365.25 days yields precisely, as the cosine term integrates to zero.[24] This derivation aligns with Keplerian orbital mechanics, where the Earth-Sun distance varies as (eccentricity ), modulating flux by , but the mean flux remains when averaged over the anomalistic year.[22] Empirical validation comes from composite satellite records (e.g., ACRIM, PMOD), which match this theoretical flux within measurement uncertainties of ~0.1%.[25]Spectral Distribution

The spectral distribution of extraterrestrial solar irradiance, known as the Air Mass Zero (AM0) spectrum, represents the wavelength-resolved power flux from the Sun incident on a surface perpendicular to the rays at the mean Earth-Sun distance, unaffected by atmospheric absorption or scattering. This distribution extends across the electromagnetic spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths, with negligible contributions below 100 nm and above 4000 nm; over 96% of the total energy lies between 200 nm and 2500 nm. Standard reference spectra, such as the ASTM E490 or the Wehrli 1985 model, tabulate irradiance values (in W/m²/nm) across this range, derived from satellite observations and atmospheric corrections of ground-based measurements.[26][27][28] The spectrum's intensity peaks near 500 nm in the blue-green visible band, reflecting the Sun's photospheric emission characteristics. Its continuum closely matches the Planck blackbody curve for an effective temperature of approximately 5772 K, calculated from the total irradiance via Stefan-Boltzmann law inversion, though the actual photosphere temperature is around 5800 K; finer deviations arise from Fraunhofer absorption lines imprinted by cooler solar atmospheric layers containing elements like hydrogen, calcium, and iron. Integrating the spectral irradiance yields the solar constant of about 1366 W/m², with energy partitioned as roughly 7% in ultraviolet (0.1–0.4 μm), 45% in visible (0.4–0.71 μm), and 48% in infrared (0.71–4.0 μm).[28][29][10] These distributions vary slightly with solar activity cycles due to changes in chromospheric and coronal emissions, particularly in ultraviolet bands (e.g., up to 1.5% fluctuation from maxima to minima in 200–300 nm), but standard AM0 spectra represent cycle-averaged values for engineering and scientific applications. High-resolution versions, such as those from the QASUMEFTS measurements or Gueymard syntheses, resolve fine structure up to 0.5 nm intervals for precise modeling in photovoltaics and radiative transfer.[30][27][31]Temporal and Spatial Variations

Solar Cycle and Short-Term Fluctuations

The solar cycle, a roughly 11-year periodicity in the Sun's magnetic activity known as the Schwabe cycle, drives systematic variations in total solar irradiance (TSI) reaching Earth.[32] Satellite measurements since 1978, compiled in composites like those from NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information, show TSI peaking at solar maximum—when sunspot numbers are highest—and reaching minima during solar quiet periods.[33] The full amplitude of this cycle-induced variation is approximately 0.1% of the mean TSI value of about 1361 W/m², corresponding to a peak-to-trough change of roughly 1.3 W/m².[34] [32] This modulation arises primarily from competing effects: dark sunspots block outgoing radiation, reducing TSI locally, while bright faculae and network structures enhance it more substantially, with the net increase at maximum driven by the latter.[35] Empirical reconstructions from datasets such as the PMOD/WRC TSI composite confirm that solar cycles 23 and 24 exhibited subdued amplitudes compared to earlier cycles like 22, with cycle 24's maximum TSI around 1361.5 W/m² and a notably low minimum in 2019.[36] [4] Solar Cycle 25, which began in late 2019 and approached maximum around mid-2024 with smoothed sunspot numbers peaking near 125, shows similar modest activity levels, yielding TSI variations consistent with prior weak cycles.[37] [38] These patterns are derived from space-based observations by instruments like those on SORCE and TSIS-1, which mitigate atmospheric interference and provide continuity across cycles.[39] [4] Superimposed on the solar cycle are short-term fluctuations in TSI, occurring over timescales from minutes to weeks, primarily linked to the evolution of solar active regions and transient events.[40] The Sun's 27-day synodic rotation brings active regions into and out of Earth's view, causing quasi-periodic dips and rises of up to 0.3% lasting several days, as sunspot groups transit the solar disk.[41] On sub-daily scales, granulation, supergranulation, and p-mode oscillations produce noise-like variations of about 0.01% over minutes, while solar flares—intense magnetic eruptions—can spike TSI by 0.01% to 0.1% in extreme cases (e.g., X-class flares) for durations of seconds to hours, though such events are rare and localized.[40] These short-term changes, observed consistently in datasets from ACRIM and VIRGO instruments, are smaller in magnitude than cycle variations but contribute to the overall irradiance variability observed at Earth's orbit.[43]Long-Term Trends and Reconstructions

Total solar irradiance (TSI) measurements from space-based instruments since 1978, including the ACRIM, ERBS, and SORCE missions, record values averaging approximately 1361 W/m² at Earth's mean orbital distance, with cyclic variations of 0.8 to 1.3 W/m² peak-to-peak over the 11-year solar cycle.[44] Composite datasets, such as the PMOD/WRC series, merge these observations and indicate no significant net trend over the satellite era (1978–2023), attributing discrepancies between composites (e.g., ACRIM's slight positive trend of ~0.03 W/m²/decade versus PMOD's flat trend) to calibration differences and instrumental degradation rather than true solar changes.[45] Recent analyses, however, suggest a possible negative linear trend of up to -0.17 W/m² over this period across some reconstructions, potentially linked to declining solar cycle amplitudes since Cycle 23, though uncertainties remain due to overlapping measurement artifacts.[45] Historical reconstructions extend TSI estimates back to 1610 using proxy records like sunspot numbers and group sunspot areas, which correlate with facular and sunspot brightness contrasts. These models, such as those by Lean et al., indicate TSI during the Maunder Minimum (1645–1715) was 1.3 to 2.0 W/m² lower than late 20th-century levels, reflecting reduced solar magnetic activity and fewer bright faculae.[46] From 1700 onward, reconstructions show a gradual rise of about 0.4% (roughly 5 W/m²) to a maximum around 1950–1960, followed by stabilization or minor decline, consistent with sunspot cycle evolution but without evidence of secular forcing beyond activity proxies.[47] Uncertainties in these sunspot-based series arise from incomplete early records and assumptions about magnetic field coverage, with alternative models using cosmogenic isotopes (e.g., ¹⁰Be from ice cores) yielding similar magnitudes but higher variability during grand minima.[48] Millennium-scale reconstructions incorporate multiple proxies, including ¹⁴C in tree rings and ¹⁰Be flux, to estimate TSI variations over the Holocene. Semi-empirical models, such as those deriving open solar magnetic flux, reconstruct TSI fluctuating within ±0.2% of modern values, with pronounced lows during periods like the Spörer Minimum (1460–1550) and Dalton Minimum (1790–1830), each ~1–2 W/m² below the 20th-century mean.[49] These long-term trends reflect stochastic solar dynamo behavior rather than deterministic external drivers, with no sustained upward trajectory over the past 1000 years; instead, current TSI levels appear near the upper envelope of natural variability, though proxy calibration against satellite data introduces factor-of-two uncertainties in absolute amplitude.[50] Wavelet-based analyses of sunspot and Ca II K-line data further support cycle-modulated trends without identifying non-solar influences in the reconstructions.[51]Orbital and Geometric Influences

Earth's orbital eccentricity of approximately 0.0167 causes the planet-Sun distance to vary annually between 0.983 AU at perihelion and 1.017 AU at aphelion, resulting in a peak-to-peak variation of about 6.9% in extraterrestrial solar irradiance.[52][53] This modulation follows the inverse square law, with maximum irradiance occurring near January 4, when Earth is closest to the Sun, increasing flux by roughly 3.4% above the mean solar constant of 1366 W/m².[54][55] The effect is superimposed on geometric factors, amplifying insolation in the Northern Hemisphere during winter despite reduced daylight from axial tilt.[56] Geometric influences arise from Earth's axial obliquity of 23.44°, which tilts the rotational axis relative to the orbital plane, producing seasonal shifts in solar position.[56][57] The solar declination angle δ, ranging from -23.44° to +23.44° over the year, quantifies this tilt's projection, approximated by δ ≈ 23.45° sin[360°(284 + n)/365], where n is the day of the year starting January 1 as n=1.[58] This drives the subsolar point's migration between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, causing zero insolation at poles beyond the Arctic/Antarctic Circles during their respective winters. The solar zenith angle θ at a location of latitude φ determines local irradiance via cos θ = sin φ sin δ + cos φ cos δ cos h, where h is the hour angle (solar time from local noon, ranging -180° to 180° daily).[59][60] Instantaneous top-of-atmosphere irradiance on a horizontal surface is thus I = S_0 (r_0 / r)^2 cos θ for cos θ > 0, and zero otherwise, with S_0 the mean solar constant and (r_0 / r)^2 the eccentricity correction.[61] Diurnal variations stem from h's progression, yielding maximum at noon (h=0) and day length 2 h_0 where cos h_0 = -tan φ tan δ. Spatially, equatorial regions receive more consistent annual totals (~ constant high cos θ average), while polar areas experience extreme seasonality with months of continuous day or night. Daily insolation averages integrate this over daylight hours, scaling with cos θ and modulated by eccentricity.[62]Measurement Techniques

Ground-Based Methods

Ground-based measurements of solar irradiance rely on surface-deployed radiometers to capture direct, diffuse, and global components with high temporal resolution, typically at 1-minute intervals or finer. These methods provide essential validation for satellite-derived data and climate models, offering uncertainties as low as 1-3% for shortwave fluxes under clear-sky conditions when properly calibrated.[63][64] Pyranometers, equipped with a thermopile sensor and a glass dome to approximate a cosine response, measure global horizontal irradiance (GHI) by integrating incoming solar radiation over a 180-degree hemispherical field of view, encompassing both direct beam and sky-diffuse components.[15][65] For diffuse horizontal irradiance (DHI), a pyranometer is deployed with a shading device, such as a disk or ball tracker, to exclude direct sunlight while capturing scattered radiation from the sky.[65] Pyrheliometers, featuring a narrow aperture (typically 5-6 degrees) aligned with the sun's disk via a tracking mechanism, quantify direct normal irradiance (DNI) perpendicular to the beam path, excluding diffuse contributions.[15][66] These instruments adhere to World Meteorological Organization (WMO) first-class standards, prioritizing thermopile detectors over photovoltaic sensors for spectral invariance and long-term stability.[67] The Baseline Surface Radiation Network (BSRN), established under the World Climate Research Programme, coordinates over 70 automated stations worldwide to deliver traceable, high-precision irradiance data for detecting decadal changes and validating global models.[68][69] BSRN protocols mandate ventilated, shaded pyranometers for GHI and DHI, sun-tracking pyrheliometers for DNI, and regular intercomparisons against the World Radiation Reference (WRR), achieving overall measurement uncertainties below 2% for DNI and 3% for GHI under optimal conditions.[63][64] Calibration follows ISO and ASTM guidelines, including ISO 9845-1 for reference spectra and ASTM E913 for pyrheliometer response, with biennial field checks to mitigate sensor degradation from dust, soiling, or thermal drift.[17] National networks, such as NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory sites, extend this framework by incorporating spectral pyranometers for wavelength-resolved measurements, aiding in aerosol and cloud effect quantification.[67] Challenges in ground-based methods include site-specific errors from horizon obstructions, atmospheric variability, and instrument fouling, necessitating site classification per ISO 9060 and automated cleaning systems at reference stations.[70] Despite these, ground observations remain the benchmark for accuracy, outperforming modeled or satellite estimates in localized validation, as evidenced by comparative analyses showing BSRN data reducing bias in solar resource assessments by up to 5%.[71][72]Space-Based Instruments

Space-based instruments have enabled precise measurements of total solar irradiance (TSI), the integrated solar radiation at the top of Earth's atmosphere, since 1978, circumventing ground-based atmospheric distortions. These instruments, primarily active cavity radiometers, detect TSI variations linked to solar activity, with absolute accuracies improving from ~0.3% in early missions to <0.04% in recent ones.[73][33] The inaugural space-based TSI observations came from the Nimbus-7 satellite, launched in October 1978, which carried the Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor (ACRIM I) and Electro-optical Far-Infrared (ERB) instruments. ACRIM I, operational until 1980 and sporadically thereafter, achieved ~0.3% absolute accuracy and detected the 11-year solar cycle modulation of ~0.1%.[74] Subsequent missions included the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS) with its non-scanning radiometer from 1984 to 2003, providing a continuous record but with noted degradation requiring corrections.[33] Advancements in the 1990s and 2000s featured the ACRIM series: ACRIM II on the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS, launched 1991) and ACRIM III on the ACRIMSAT platform (launched 2000), both yielding precisions of ~0.001% per year after recalibrations at facilities like the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) Total Solar Irradiance Radiometry Facility.[74] The Variability of solar IRradiance and Gravity Oscillations (VIRGO) instrument on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO, launched 1995) complemented these with three Sun-like active cavity radiometers, though its data required adjustments for degradation.[75] The Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE), launched in January 2003 and decommissioned in 2020, introduced the Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM), a bolometer-based sensor with 350 ppm absolute accuracy and <10 ppm/year stability, establishing a revised quiet-Sun TSI value of ~1361 W/m².[39][73] The Total and Spectral Solar Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1), deployed to the International Space Station in December 2017, continues TIM heritage measurements with a precision radiometer, maintaining the TSI record through Solar Cycle 24 and into Cycle 25, achieving uncertainties below 0.01%.[76] These datasets form composites like the PMOD/WRC record, which reconciles overlaps but has sparked debate over degradation models, with the ACRIM composite suggesting a possible long-term TSI rise of ~0.03%/decade not evident in PMOD adjustments.[75][33]Calibration Issues and Historical Discrepancies

Space-based measurements of total solar irradiance (TSI) face significant calibration challenges due to instrument degradation from ultraviolet exposure, which alters cavity blackening and detector sensitivity over time, necessitating ongoing corrections that introduce uncertainties of up to several tenths of a percent.[77] [78] For instance, radiometers like those on the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) require degradation tracking via exponential or linear decay models applied to individual channels, as sensitivity drifts can mimic solar variability if unaccounted for.[79] [80] Ground-based pyrheliometers encounter additional issues from atmospheric interference and infrequent absolute calibrations against cryogenic radiometers, leading to systematic biases in historical records of surface irradiance.[81] Historical discrepancies in TSI records stem from inconsistencies in bridging data gaps and absolute scale alignments across satellite missions, with scale differences of up to 0.4% attributed to metrological errors in sensor design and pre-launch calibrations.[82] A prominent example is the "ACRIM gap" between the Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor (ACRIM1) on the Solar Maximum Mission (ending 1989) and ACRIM2 on the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (starting 1991), where overlapping data from the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS) were adjusted differently: the ACRIM composite applies minimal corrections to preserve an upward trend of 0.037% per decade (about 0.5 W/m²) from 1980 to 2000, while the PMOD/WRC composite incorporates degradation corrections to ERBS data, yielding a flat or slightly declining trend over the same period.[83] [84] These methodological choices reflect debates over instrument stability, with ACRIM proponents arguing that PMOD adjustments artificially suppress a secular rise potentially linked to solar activity, whereas PMOD advocates cite independent validations like ERBS non-solar channels supporting degradation trends.[85] [86] Early satellite-era measurements, such as those from Nimbus-7 starting in 1978, established the TSI baseline around 1366 W/m² but required revisions based on later missions like SORCE and TSIS-1, which revealed spectral discrepancies—e.g., TSIS-1 showing up to 6% lower infrared irradiance compared to prior references—highlighting propagated calibration errors from pre-space standards.[87] [79] Such issues have fueled reconstructions questioning long-term trends, with some analyses attributing apparent declines since the 1980s to uncorrected degradation rather than solar dimming, while others defend composites like ACRIM for capturing facular brightening effects.[88] [89] Ongoing efforts, including data fusion with stochastic noise models, aim to reconcile these by prioritizing overlap periods and proxy validations, though uncertainties persist at the 0.1% level for decadal reconstructions.[36]Recent Developments in Precision Measurement

The Total and Spectral Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1), deployed on the International Space Station in November 2017, represents a major advancement in space-based precision measurements of both total solar irradiance (TSI) and spectral solar irradiance (SSI), succeeding the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) mission that operated from 2003 to 2020.[90] TSIS-1's Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) achieves measurement precision better than 0.001% per year for TSI, enabling detection of subtle solar cycle variations with uncertainties reduced to approximately 0.03% absolute accuracy through electrical substitution radiometry traceable to International System of Units (SI) standards.[41] This surpasses prior instruments like those on SORCE, which had degradation rates up to 0.3% per decade, by incorporating redundant detectors and in-flight calibration to minimize systematic errors.[91] The Spectral Irradiance Monitor (SIM) on TSIS-1 extends SSI observations across 200–2400 nm with enhanced absolute scale accuracy of about 0.5–1% in the ultraviolet and visible bands, facilitated by improved optical design, including double monochromators and prism pre-dispersers that reduce stray light by factors exceeding 10^6 compared to SORCE SIM.[79] Early TSIS-1 SIM data from 2018–2023 reveal spectral discrepancies with reference models, such as up to 6% lower irradiance in the infrared near 2400 nm and ~0.5% increases in select visible wavelengths, refining understanding of solar output variability during solar cycles 24–25.[79] These improvements stem from pre- and post-launch calibrations using synchrotron-based SI-traceable sources unavailable during SORCE's era, yielding long-term stability of 0.1% per decade or better.[91] Ground-based efforts complement space measurements, with advancements in cavity radiometers and spectroradiometers achieving TSI precision nearing space-based levels through automated tracking and real-time corrections for atmospheric effects, as demonstrated in recent traceable spectroradiometer deployments that integrate high-resolution scans with uncertainties below 0.2%.[92] By 2025, these developments have lowered overall TSI record uncertainties to ~0.1% for composite datasets spanning four decades, enhancing quantification of solar forcing in climate models by distinguishing radiative changes of 0.1–0.2 W/m² from instrumental artifacts.[93] Ongoing analyses, including those from TSIS-1's descending phase coverage of solar cycle 25, continue to validate minimal long-term TSI trends below detection thresholds amid historical debates over composite reconstructions.[41]Propagation to Earth's Surface

Atmospheric Absorption and Scattering Processes

Solar radiation traversing Earth's atmosphere is attenuated primarily through absorption by gaseous constituents and scattering by molecules and particles. Absorption removes photons, converting their energy into heat within the atmosphere, with key absorbers including ozone (O₃), which strongly attenuates ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths in the Hartley band (200–310 nm), effectively blocking nearly all UV-C (100–280 nm) and much of UV-B (280–315 nm) radiation.[94] Water vapor (H₂O) dominates near-infrared absorption beyond 700 nm, while oxygen (O₂), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and minor gases like methane (CH₄) contribute across visible and infrared spectra, collectively accounting for approximately 16% of incoming shortwave radiation under clear-sky conditions.[95] These processes vary with atmospheric path length, increasing attenuation at higher air masses (e.g., near horizon) due to longer optical paths through absorbing layers.[96] Scattering redirects radiation without net energy loss, dividing it into direct beam (unscattered) and diffuse components reaching the surface. Rayleigh scattering, dominant for molecules like N₂ and O₂, follows λ⁻⁴ wavelength dependence, preferentially dispersing shorter blue-violet light and producing the clear-sky blue hue while backscattering roughly 5–10% of total solar flux to space.[4] Mie scattering by larger aerosols, dust, and cloud droplets is less wavelength-selective, often yielding forward-scattered haze or white glare, with efficiency scaling with particle size relative to wavelength; aerosol optical depth can enhance total scattering by 10–20% in polluted conditions.[97] Clouds amplify Mie effects, reflecting or scattering up to 50–80% of incident radiation depending on optical thickness and phase (liquid vs. ice).[98] Globally averaged, these processes result in the atmosphere absorbing 23–26% of top-of-atmosphere solar irradiance (approximately 340 W/m² from a 1361 W/m² total), with scattering contributing to an effective planetary albedo of about 0.30, including backscattered fractions from molecules, aerosols, and surfaces.[98][99] Variations arise from vertical profiles—e.g., stratospheric ozone peaks absorption aloft— and horizontal factors like latitude, season, and aerosol loading, modulating surface insolation by 10–50% relative to extraterrestrial values.[100] Empirical radiative transfer models, such as MODTRAN or libRadtran, quantify these via line-by-line spectral calculations, confirming gaseous absorption bands and scattering asymmetries.[96]Angular and Positional Effects

The angular incidence of solar radiation on Earth's surface is determined by the solar zenith angle θ_z, the angle between the Sun's rays and the local zenith direction. The direct normal irradiance (DNI) projected onto a horizontal surface yields global horizontal irradiance (GHI) components where the beam contribution is DNI × cos(θ_z), accounting for the foreshortening effect that spreads radiation over a larger area as θ_z increases from 0° (overhead) to 90° (horizon). This cosine projection reduces effective irradiance at oblique angles, with cos(θ_z) dropping to zero at sunrise and sunset.[59][101] The value of θ_z depends on geographic position and time: cos(θ_z) = sin(φ) sin(δ) + cos(φ) cos(δ) cos(h), where φ is latitude, δ is solar declination, and h is the hour angle (h = 15° × (local solar time - 12 h)). Solar declination δ varies seasonally due to Earth's 23.44° axial tilt, approximated by δ = 23.45° × sin(360° × (284 + n) / 365), with n as the day of the year (January 1 = n=1); δ reaches +23.45° near the June solstice and -23.45° near December. At the equator (φ=0°), θ_z ≈ |δ| at noon, enabling near-overhead Sun twice yearly, while at higher latitudes, noon θ_z = |φ - δ|, often exceeding 60° and limiting peak irradiance.[59][102] Positional effects from latitude φ dominate annual and latitudinal variations in surface irradiance: higher |φ| increases average θ_z, lengthening atmospheric path lengths (by 1/cos(θ_z)) and reducing transmittance, while also shortening daylight hours defined by cos(h_sr) = -tan(φ) tan(δ) for sunrise/sunset hour angle h_sr. Equatorial zones (φ ≈ 0°) average ~12-hour days and smaller θ_z, yielding annual GHI up to 2,500 kWh/m², compared to ~1,000 kWh/m² at 60° latitude due to prolonged low-angle or absent sunlight in winter. Longitude influences local solar time and thus diurnal θ_z profiles but averages out over time zones for site assessments. These effects compound with atmospheric processes, explaining global solar resource gradients observed in maps from sources like the Global Solar Atlas.[103][59][104] For non-horizontal surfaces, the angle of incidence θ replaces θ_z, incorporating surface tilt β and azimuth γ via cos(θ) = sin(δ) sin(φ) cos(β) + ... (extended formula), enabling optimization for applications like photovoltaics where tracking minimizes θ to approach cos(0°)=1. Sunrise/sunset occur when θ_z=90°, but refraction extends effective daylight by ~2-3 minutes. Precise computations use algorithms like NREL's Solar Position Algorithm, achieving ±0.0003° accuracy for engineering.[105][106]Modeling and Resource Mapping

Solar irradiance modeling for surface applications relies on parametric clear-sky models as foundational tools to estimate radiation under cloudless atmospheres, incorporating effects from Rayleigh scattering, aerosol absorption, water vapor, and ozone. The Bird model, a broadband algorithm introduced in 1981, calculates direct normal irradiance (DNI), diffuse horizontal irradiance (DHI), and global horizontal irradiance (GHI) using inputs such as aerosol optical depth (typically 0.1-0.3 for clean air), precipitable water (around 1-2 cm), and ground albedo (0.2 for land).[107] This model solves radiative transfer equations approximately, yielding DNI values up to 1000 W/m² at sea level under high solar elevation.[108] Advanced clear-sky formulations, such as the Ineichen-Perez model from 2002, reduce complexity by employing the Linke turbidity factor (TL, ranging 2-5 globally) to encapsulate integrated atmospheric optical depth, enabling rapid computation of GHI and DNI without detailed vertical profiles.[109] Validation studies show these models achieve root mean square errors of 5-10% against measurements in mid-latitudes under low-aerosol conditions.[110] For tilted surfaces, transposition models like the Perez anisotropic model account for sky brightness and diffuse fraction, improving estimates for photovoltaic array orientations by factoring in horizon shading and view factors.[110] All-sky modeling extends clear-sky baselines by integrating cloud opacity derived from satellite imagery or numerical weather prediction, often via separation techniques that scale clear-sky values with a cloud index (0 for overcast, 1 for clear). Hybrid approaches combine physical models with machine learning for short-term forecasting, but long-term resource assessment prioritizes satellite-based climatologies over purely empirical methods due to physical interpretability.[111] Resource mapping generates geospatial datasets of long-term average irradiances to evaluate solar energy potential, fusing geostationary satellite observations (e.g., Meteosat, GOES series) with ground pyranometer networks for validation. The Global Solar Atlas (GSA) version 2.0, released in 2019 by the World Bank ESMAP and Solargis, processes 15-30 years of data into 250-meter resolution grids of P90 annual GHI (e.g., 1800-2200 kWh/m²/year in North Africa) and DNI, employing REST2 clear-sky library for lookup-table efficiency and McClear model for cloud corrections.[112][113] Uncertainties in maps arise from aerosol variability and cloud detection errors, typically ±5% in well-monitored regions like Europe, higher (±10-15%) in data-sparse tropics.[114] These maps support site selection, revealing DNI hotspots above 2000 kWh/m²/year in arid zones essential for concentrating solar power.[115]Applications in Science and Engineering

Solar Energy Systems