Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Northern and southern China

View on WikipediaNorthern China (Chinese: 中国北方 or 中国北部; lit. 'China's North') and southern China (Chinese: 中国南方 or 中国南部; lit. 'China's South')[note 1] are two approximate regions that display certain differences in terms of their geography, demographics, economy, and culture.

Extent

[edit]The Qinling–Daba Mountains serve as the transition zone between northern and southern China. They approximately coincide with the 0 degree Celsius isotherm in January, the 800 millimetres (31 in) isohyet, and the 2,000-hour isohel.[1] The Huai River basin serves a similar role,[2][3] and the course of the Huaihe has been used to set different policies to the north and the south.[4]

History

[edit]Historically, populations migrated from the north to the south, especially its coastal areas and along major rivers.[5][6]

After the fall of the Han dynasty, The Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589) ruled their respective part of China before re-uniting under the Sui dynasty.[7]

During the Qing dynasty, regional differences and identification in China fostered the growth of regional stereotypes. Such stereotypes often appeared in historic chronicles and gazetteers and were based on geographic circumstances, historical and literary associations (e.g. people from Shandong, were considered upright and honest) and Chinese cosmology (as the south was associated with the fire element, Southerners were considered hot-tempered).[8] These differences were reflected in Qing dynasty policies, such as the prohibition on local officials to serve their home areas, as well as conduct of personal and commercial relations.[8] In 1730, the Kangxi Emperor made the observation in the Tingxun Geyan (庭訓格言):[8][9]

The people of the North are strong; they must not copy the fancy diets of the Southerners, who are physically frail, live in a different environment, and have different stomachs and bowels.

— the Kangxi Emperor, Tingxun Geyan (《庭訓格言》)

During the Republican period, Lu Xun, a major Chinese writer, wrote:[10]

According to my observation, Northerners are sincere and honest; Southerners are skilled and quick-minded. These are their respective virtues. Yet sincerity and honesty lead to stupidity, whereas skillfulness and quick-mindedness lead to duplicity.

— Lu Xun, Complete works of Lu Xun (《魯迅全集》), pp. 493–495.

Today

[edit]Climate

[edit]Northern regions of China have long winters that are cold and dry, often below freezing, and long summers that are hot and humid.[11] Transitional periods are short. The ecology is simple and not resilient to droughts.[6]

Many southern regions are subtropical and green year round. The winters are short. They often experience typhoons and the East Asian monsoon in the summer.[12] The ecology is complex, and floods are more common.[6]

Diet and produce

[edit]

The northern regions are easier to cultivate.[6] Hardy crops such as corn, sorghum, soybeans, and wheat are grown, and one to two crops are produced each year.[8] The growing season lasts four to six months. Wheat-based food such as bread, dumplings, and noodles are more common.[13][11]

Cultivation of the southern regions began later in history.[6] Warm temperatures and abundant rainfall help produce rice and tropical fruits.[11] Two to three crops can be grown each year, and the growing season lasts nine to twelve months.[8] Rice-based food is more common.[13][11]

Language and people

[edit]

Jones Lamprey, a British army surgeon in 1868,[15] writes that northerners have lighter skin tones than southerners, although the shade can change greatly from season to season depending on an individual's exposure to sunlight when performing manual labor outdoors.[16] Northerners are often taller than southerners.[17]

Variants of Mandarin are widely spoken in northern regions and often with a rhotic accent.[6][16] Ethnic groups are comparatively more diverse in southern regions.[8] Rhotic accent is usually absent from the Mandarin spoken there. Different dialects are less mutually intelligible, and additional languages such as Cantonese or Hokkien are spoken.[16] Patrilineage organizations are larger and more integrated in rural southern regions, possibly due to merges and competition for territory.[6]

A series of studies on regional differences in China suggest that people from places that grow wheat have different social styles and thought styles from those in rice-growing regions.[18][19][20] Respondents from northern China are found to be more individualistic, think more analytically, and more open to strangers. Those from the southern regions are more likely to think holistically, interdependent, and draw a larger distinction between friends and strangers. The difference was attributed to the growing of rice, which often requires the sharing labor and managing shared irrigation infrastructure.[19][21][22]

Transportation

[edit]Traveling between places tends to be easier in northern regions where the terrain is more even.[6]

Economy

[edit]

As China modernized, the north initially developed faster during the era of planned economic policies and Soviet aid, forming a concentration of construction and resource extraction industries. After market reforms, however, the south took the lead due to manufacturing and eventually high-tech industries, as well as continued internal migration into the region. The north's share of China's GDP decreased from 42.9% in 2012 to 35.4% in 2019.[5]

Health

[edit]A research showed that life expectancy was slightly higher in southern China compared to northern China. In 2018, it was 76.66 years for north and 77.35 for south.[23] The shorter life expectancy in northern China can be partly attributed to outdoor air pollution due to winter district heating.[24] According to the data from a survey in 2011, people in southern China were 10.51% less likely to be obese and overweight compared to the North.[25]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Also referred to in China as simply the north (Chinese: 北方; pinyin: Běifāng) and the south (Chinese: 南方; pinyin: Nánfāng).

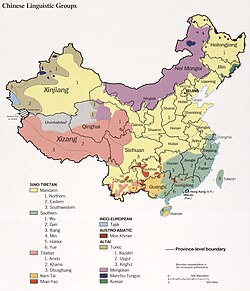

- ^ The map shows the distribution of linguistic groups according to historical majority ethnic groups, which may have shifted due to prolonged internal migration and assimilation.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Lan, Xincan; Li, Wuyang; Tang, Jiale; Shakoor, Abdul; Zhao, Fang; Fan, Jiabin (28 April 2022). "Spatiotemporal variation of climate of different flanks and elevations of the Qinling–Daba mountains in China during 1969–2018". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 6952. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.6952L. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10819-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9050673. PMID 35484392.

- ^ Yin, Yixing; Chen, Haishan; Wang, Guojie; Xu, Wucheng; Wang, Shenmin; Yu, Wenjun (1 May 2021). "Characteristics of the precipitation concentration and their relationship with the precipitation structure: A case study in the Huai River basin, China". Atmospheric Research. 253 105484. Bibcode:2021AtmRe.25305484Y. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2021.105484. ISSN 0169-8095.

- ^ Xia, Jun; Zhang, Yongyong; Zhao, Changsen; Bunn, Stuart E. (August 2014). "Bioindicator Assessment Framework of River Ecosystem Health and the Detection of Factors Influencing the Health of the Huai River Basin, China". Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. 19 (8). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0000989. hdl:10072/66836. ISSN 1084-0699.

- ^ Gao, Yannan; Sampattavanija, San. "China's Huai River Policy and Population Migration: A U-Shaped Relationship". Nova Science Publishers. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Weekend Long Read: Why China's North-South Economic Gap Keeps Getting Bigger - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Xuefeng, He (7 March 2022). Northern and Southern China: Regional Differences in Rural Areas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-40262-9.

- ^ Lewis, Mark Edward (30 April 2011). China Between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06035-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Richard Joseph (1994). China's cultural heritage: the Qing dynasty, 1644–1912 (2 ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-1347-4.

- ^ Hanson, Marta E. (July 2007). "Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662–1722)" (PDF). Pacific Rim Report (43). San Francisco: Center for the Pacific Rim, University of San Francisco: 7, 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Young, Lung-Chang (Summer 1988). "Regional Stereotypes in China". Chinese Studies in History. 21 (4): 32–57. doi:10.2753/csh0009-4633210432. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Regions of Chinese food-styles/flavors of cooking". regional cuisines. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009.

- ^ Zhu, Hua (1 March 2017). "The Tropical Forests of Southern China and Conservation of Biodiversity". The Botanical Review. 83 (1): 87–105. Bibcode:2017BotRv..83...87Z. doi:10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2. ISSN 1874-9372. S2CID 29536766.

- ^ a b Eberhard, Wolfram (December 1965). "Chinese Regional Stereotypes". Asian Survey. 5 (12). University of California Press: 596–608. doi:10.2307/2642652. JSTOR 2642652.

- ^ Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1990.

- ^ "Jones Lamprey | Historical Photographs of China". hpcbristol.net. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Lamprey, J. (1868). "A Contribution to the Ethnology of the Chinese". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 6: 101–108. doi:10.2307/3014248. ISSN 1368-0366. JSTOR 3014248.

- ^ Lu, Guoguang; Yang, Zhihui; Zhang, Yan; Lu, Shengxu; Gong, Siyuan; Li, Tingting; Shen, Yijie; Zhang, Sihan; Zhuang, Hanya (2022). "Geographic latitude and human height - Statistical analysis and case studies from China". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 15 (335). Bibcode:2022ArJG...15..335L. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-09335-x.

- ^ Talhelm, Thomas; Dong, Xiawei (27 February 2024). "People quasi-randomly assigned to farm rice are more collectivistic than people assigned to farm wheat". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1782. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1782T. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-44770-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10899190. PMID 38413584.

- ^ a b Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S.; Shimin, C.; Duan, D.; Lan, X.; Kitayama, S. (9 May 2014). "Large-Scale Psychological Differences Within China Explained by Rice Versus Wheat Agriculture". Science. 344 (6184): 603–608. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..603T. doi:10.1126/science.1246850. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24812395.

- ^ Talhelm, Thomas; Zhang, Xuemin; Oishi, Shigehiro (6 April 2018). "Moving chairs in Starbucks: Observational studies find rice-wheat cultural differences in daily life in China". Science Advances. 4 (4) eaap8469. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.8469T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap8469. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5916507. PMID 29707634.

- ^ Talhelm, Thomas; Oishi, Shigehiro (2018). "How Rice Farming Shaped Culture in Southern China". In Uskul, Ayse (ed.). Socio-Economic Environment and Human Psychology: Social, Ecological, and Cultural Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–76. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190492908.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-049290-8. LCCN 2017046499. SSRN 3199657.

- ^ Bray, Francesca (1994). The Rice Economies: Technology and Development in Asian Societies. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08620-3.

- ^ Mengqi Wang; Yi Huangyi (18 September 2020). "Why Residents in Southern China Live Longer Than Those in Northern China?". doi:10.21203/rs.2.17818/v1. S2CID 241548808.

Table 1, Page number 2

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Yuyu Chen; Avraham Ebenstein; Michael Greenstone; Hongbin Li (2013). "Evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China's Huai River policy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (32): 12936–12941. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012936C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300018110. PMC 3740827.

- ^ Daisheng Tang; Tao Bu (2020). "Differences in Overweight and Obesity between the North and South of China". Research gate. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

Page number 789, Paragraph 2

Further reading

[edit]- Brues, Alice Mossie (1977). People and Races. Macmillan series in physical anthropology. New York, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-315670-0.

- Du, Ruofu; Yuan, Yida; Hwang, Juliana; Mountain, Joanna; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca (1992). "Chinese Surnames and the Genetic Differences between North and South China". Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series (5): 1–93. ISSN 2409-2878. JSTOR 23825835.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Liu, Kwang-chang. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, Stephen L. (2000). "Richer and Taller: Stature and Living Standards in China, 1979-1995". The China Journal (44): 1–39. doi:10.2307/2667475. ISSN 1324-9347. JSTOR 2667475. PMID 18411497.

- Muensterberger, Warner (1951). "Orality and Dependence: Characteristics of Southern Chinese." In Psychoanalysis and the Social Sciences, (3), ed. Geza Roheim (New York: International Universities Press).

Northern and southern China

View on GrokipediaGeographical and Environmental Foundations

Defining Boundaries and Extent

The division between northern and southern China is primarily defined by the Qinling-Huaihe Line, a geographical demarcation extending from the Qinling Mountains in the west (spanning Shaanxi and Gansu provinces) eastward to the Huai River valley in Anhui and Jiangsu provinces, roughly aligning with the 33rd parallel north between latitudes 31°20′N to 35°10′N and longitudes 103°48′E to 120°54′E.[10][1] This line approximates key climatic thresholds, including the 0°C average January isotherm—separating colder northern winters from milder southern ones—and the 800 mm annual precipitation isohyet, which distinguishes semi-arid to temperate northern zones from humid subtropical southern areas conducive to double-cropping rice agriculture.[11][12] While not an administrative boundary, it has served as a practical divide since at least the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), reflecting differences in vegetation, hydrology, and human adaptation, though transitional zones like parts of Henan and Anhui provinces exhibit hybrid characteristics.[2] Northern China's extent north of the Qinling-Huaihe Line covers the expansive North China Plain (Huang-Huai-Hai Plain), Loess Plateau, and extends into the arid basins of the northwest, Mongolian-Manchurian grasslands, and northeastern highlands, encompassing roughly 4 million square kilometers or about 42% of China's total land area of 9.6 million square kilometers.[13] Key provinces and regions include Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Henan (northern parts), Shaanxi (northern parts), Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Gansu (northern parts), Ningxia, and Xinjiang, dominated by the Yellow River basin and featuring continental climates with pronounced seasonal extremes, loess soils, and reliance on wheat and millet cultivation.[14] This region, historically the cradle of Chinese civilization with sites like the Yellow River's middle reaches dating to 5000 BCE, supports over 500 million people as of recent censuses, though population density varies from urban concentrations in the Beijing-Tianjin corridor to sparse herding communities in the northwest.[9] Southern China's boundaries south of the line include the Yangtze River basin, southeastern hills, and coastal plains extending to Hainan Island and the South China Sea, covering approximately 5.6 million square kilometers with diverse terrains from karst plateaus in Guangxi to river deltas in the Pearl River system.[13] It comprises provinces and regions such as Shanghai, Jiangsu (southern parts), Zhejiang, Anhui (southern parts), Jiangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Sichuan (eastern parts), Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hainan, and Taiwan (in geopolitical claims), characterized by monsoon climates enabling rice paddies, tea plantations, and fisheries, with population exceeding 800 million concentrated in eastern urban agglomerations like the Yangtze Delta as of 2020 data.[14] The divide's permeability is evident in historical migrations and modern infrastructure like the South-to-North Water Diversion Project (initiated 2002), which channels southern Yangtze waters northward across the line to mitigate northern water scarcity.[7]Climate, Terrain, and Natural Resources

Northern China features a temperate monsoon climate characterized by cold, dry winters with average January temperatures often below freezing and hot, humid summers, with annual precipitation typically ranging from 400 to 800 mm, concentrated in the summer months.[15] In contrast, southern China exhibits a humid subtropical climate with milder winters (average January temperatures around 5–10°C) and warm, rainy summers, receiving over 1,000 mm of annual precipitation, often exceeding 1,500 mm in southeastern areas due to the influence of the East Asian monsoon.[16] These climatic disparities arise from latitudinal variations and the blocking effect of the Qinling Mountains-Huai River line, which separates the colder, drier continental air masses of the north from the warmer, moister maritime influences in the south.[7] The terrain of northern China is dominated by expansive alluvial plains, such as the North China Plain formed by Yellow River sediments, interspersed with the eroded Loess Plateau, which features deep gullies and yellow silt soils prone to erosion and flooding.[17] Southern China, however, consists primarily of rugged mountains, hills, and dissected plateaus, including ranges like the Nanling and Wuyi Mountains, with narrower river valleys and karst landscapes in regions like Guangxi, facilitating denser river networks but limiting large-scale flatland agriculture.[18] This north-south topographic gradient contributes to varying vulnerability to natural hazards: northern areas face dust storms and desertification from the Gobi's proximity, while southern terrains experience frequent landslides and typhoon-induced flooding.[13] Natural resources in northern China are heavily skewed toward fossil fuels and ferrous minerals, with coal reserves totaling over 334 billion tons concentrated in provinces like Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Heilongjiang, accounting for the majority of China's production and supporting heavy industry.[19] Iron ore deposits are also prominent in the north, particularly in Hebei and Liaoning, underpinning steel output. Southern China, by comparison, holds significant non-ferrous mineral reserves, including over 60% of global tungsten supply from mines in Hunan, Jiangxi, and Guangdong, alongside antimony, tin, and bismuth, with hydropower potential from rivers like the Yangtze generating substantial renewable energy.[20] Rare earth elements, while mined primarily at Bayan Obo in the north, undergo much processing in southern facilities, though resource extraction in the south focuses more on associated minerals like fluorite and barite.[21] These distributions reflect geological formations: sedimentary basins in the north for coal and oil shales, versus igneous and metamorphic rocks in the south for strategic metals.[22]Historical Development

Ancient and Prehistoric Origins

Human occupation in China dates back to the Paleolithic era, with archaeological evidence indicating regional variations in tool technologies between northern and southern areas as early as 2.5 million years ago. In northern China, particularly along the Yellow River basin, sites reveal chopper-chopping tools and core-flake industries, reflecting adaptations to open, arid environments conducive to hunting and gathering.[23] In contrast, southern China, including the Lingnan region (Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan), features pebble-tool traditions with bifacial chopping tools and microliths, suited to forested, subtropical landscapes that supported diverse foraging strategies.[24] [23] These differences in lithic assemblages suggest early environmental adaptations that laid foundational distinctions, though population continuity and gene flow persisted across regions.[25] The Neolithic period (ca. 7000–2000 BCE) marked the crystallization of north-south cultural divergences through sedentary agriculture and complex societies. Northern China's Yangshao culture (5000–3000 BCE), centered in the middle Yellow River valley, emphasized millet cultivation, painted pottery, and village settlements, with sites like those in Henan province demonstrating organized dryland farming and early social hierarchies.[26] [27] Southern equivalents, such as the Hemudu culture (5500–3300 BCE) in the Yangtze Delta near Hangzhou Bay, pioneered wet-rice agriculture, evidenced by carbonized rice remains and pile-dwelling structures adapted to marshy terrains.[28] Further south, the Liangzhu culture (3300–2300 BCE) in the Yangtze lowlands showcased advanced jade working, hydraulic engineering, and stratified burials, indicating proto-urban complexity distinct from northern painted-ceramic traditions.[29] [28] These parallel developments along major river systems—Yellow River in the north for millet and Yangtze in the south for rice—fostered ecological and technological specializations that presaged enduring regional identities.[30] Ancient DNA analyses corroborate these archaeological patterns, revealing distinct ancestral components with Neolithic admixture shaping modern distributions. Genomes from northern Neolithic sites, such as those in the Yellow River Bend, show continuity with ancient northern East Asian hunter-gatherers, with limited early southern influence until Bronze Age exchanges.[31] Southern ancient populations, including those from Yangtze sites, exhibit higher affinity to Austroasiatic-related groups, with northward gene flow minimal until later migrations.[32] A southward population shift during the Neolithic, driven by agricultural expansions, introduced northern Yellow River ancestry into southern groups, reducing but not eliminating genetic clines observed in contemporary Han Chinese.[32] [33] This admixture, quantified at contributing to 0.37% of total Han genetic variance along a north-south axis, underscores how prehistoric mobility overlaid initial regional isolations without fully homogenizing populations.[33] By the late Neolithic, these dynamics had established the substrate for imperial-era integrations, where northern polities like the Shang (ca. 1600–1046 BCE) in the Yellow River heartland exerted cultural dominance over southern peripheries.[34]Imperial Dynasties and Regional Dynamics

The earliest imperial dynasties, including the semi-legendary Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE), and Zhou (1046–256 BCE), emerged in northern China along the Yellow River basin, where fertile loess soils supported millet and wheat agriculture, enabling the development of centralized polities with capitals such as Anyang for the Shang.[35] The Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) unified China from its northwestern base at Xianyang (near modern Xi'an), imposing standardized systems like weights, measures, and script that facilitated integration but originated from northern military expansion southward.[36] The subsequent Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) maintained northern capitals at Chang'an (Xi'an) and Luoyang, consolidating imperial rule through bureaucratic expansion and the Silk Road, though southern regions began contributing rice-based taxation by the Eastern Han period.[36] Following the Han collapse, China fragmented into the Three Kingdoms (220–280 CE) and Jin dynasty (265–420 CE), with northern regimes like Wei facing internal strife and southern polities like Wu emphasizing Yangtze River commerce; the Western Jin briefly reunified from Luoyang before succumbing to northern nomadic incursions, prompting elite flight southward to Jiankang (Nanjing).[37] The Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589 CE) exemplified regional divergence: northern states, often founded by Xianbei and other steppe groups like the Northern Wei (capital at Pingcheng, later Luoyang), adopted cavalry tactics and sinicized governance amid frequent regime changes, while southern dynasties (Liu Song, Qi, Liang, Chen, capitals at Nanjing) preserved Han cultural continuity with greater stability due to natural barriers like the Huai River and Yangtze, though plagued by aristocratic infighting.[35] The Sui (581–618 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) reunified from northern capitals—Daxing (Xi'an) and Chang'an—leveraging northern military prowess, but Tang prosperity increasingly drew on southern rice surpluses, with the Grand Canal (completed 610 CE) linking northern politics to southern grain supplies.[37] The Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) marked a pivotal shift: northern Song capitals at Kaifeng endured Liao and Jin pressures, but after the Jurchen conquest of the north in 1127 CE, the southern Song relocated to Lin'an (Hangzhou), where economic output—driven by Champa rice strains enabling double cropping and yielding up to 3.5 times northern wheat per mu—surpassed the north, with Yangtze Delta GDP estimates indicating 50-60% of imperial totals by 1200 CE.[38] Subsequent Mongol Yuan (1271–1368 CE, capital Dadu/Beijing), Ming (1368–1644 CE, initial Nanjing then Beijing from 1421), and Manchu Qing (1644–1912 CE, Beijing) restored northern political dominance, relying on steppe-derived horsemanship for conquest while extracting southern revenues via enhanced taxation and waterways.[36] These dynamics reflected causal environmental and strategic factors: northern China's proximity to Eurasian steppes invited recurrent invasions—over 20 major nomadic incursions from Han to Song—fostering adaptive militarism and ethnic admixture, as seen in the sinicization of Tuoba Wei elites; southern China's humid climate and riverine terrain supported denser populations (reaching 60 million in south vs. 30 million north by late Tang) and commercialization, shifting imperial vitality southward post-An Lushan Rebellion (755–763 CE), when northern depopulation halved taxable households.[39] Yet political capitals remained northern to control steppe frontiers, perpetuating a north-south asymmetry where military power anchored in the arid plains subsidized southern agrarian wealth.[35]Modern Era: Republican, Communist, and Reform Periods

The Republican era (1912–1949) featured pronounced north-south political divisions, with northern China dominated by Beiyang warlords and fragmented cliques following the Qing collapse, while southern regions maintained stronger continuity under Kuomintang (KMT) influence centered in Guangzhou.[40] This divide culminated in the Northern Expedition (1926–1928), a KMT-led campaign that nominally unified the country under Nanjing's rule but left lingering regional tensions, exacerbated by Japanese invasion starting in northern Manchuria in 1931 and escalating to full-scale war in 1937, which initially devastated northern industrial bases like those in Hebei and Shanxi.[41] Civil war dynamics further highlighted differences, as Communist forces gained rural traction in the north, leveraging peasant support in wheat-growing areas, whereas KMT control was firmer in southern urban and coastal centers.[42] Under Communist rule from 1949, Mao Zedong's policies prioritized heavy industrialization in the north, exploiting coal and iron resources in provinces like Shanxi and Liaoning to build state-owned enterprises, contrasting with the south's emphasis on light industry and agriculture.[43] The Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) amplified regional vulnerabilities: northern wheat-dependent areas suffered higher excess mortality from the ensuing famine—estimated at 15–55 million deaths nationwide—due to crop failures from poor weather, excessive grain procurement for urban industry, and misguided communal farming that disrupted traditional practices, while southern rice paddies offered greater resilience through double-cropping and irrigation.[44][45] Famine death rates were reportedly 2–3 times higher in northern provinces like Anhui (often grouped with north-central) compared to southern Guangdong, underscoring causal links between monoculture wheat systems and centralized resource extraction.[44] Post-1978 reforms under Deng Xiaoping shifted priorities toward coastal export-led growth, establishing Special Economic Zones (SEZs) primarily in the south, such as Shenzhen in Guangdong in 1980, attracting foreign direct investment and fostering township-village enterprises (TVEs) that leveraged southern proximity to trade routes.[46] The household responsibility system, implemented nationwide by 1984, decollectivized agriculture and boosted grain output from 300 million tons in 1977 to 400 million tons, but southern regions adapted faster due to denser populations, better infrastructure, and market access, leading to rapid urbanization and non-farm employment.[47] This coastal bias widened economic gaps: by the 1990s, per capita GDP in southern Guangdong exceeded northern Hebei's by over 200%, with northern heavy industries stagnating amid inefficient state firms and resource depletion.[46] Rural reforms inadvertently entrenched disparities, as southern households diversified into manufacturing, while northern ones remained tied to declining extractive sectors, prompting massive southbound migration exceeding 100 million by 2000.[48]Demographic and Biological Variations

Population Distribution and Ethnic Composition

The Qinling–Huaihe Line serves as the conventional geographical divide between northern and southern China, influencing population patterns through differences in climate, soil fertility, and historical settlement. Analysis of census data from 1982 to 2010 indicates that approximately 58% of China's population resided south of this line, compared to 42% north, with the ratio exhibiting stability over this period due to persistent environmental constraints in the north limiting carrying capacity.[1] This distribution reflects higher population densities in the south, where subtropical conditions and extensive river systems support intensive agriculture and urbanization; for instance, provinces like Guangdong and Jiangsu exceed 500 people per square kilometer, far surpassing northern averages.[49] Extrapolating to the 2020 census total of 1,411,778,724, the southern share approximates 818 million, while the north holds about 594 million, though official breakdowns strictly along the line remain unpublished and recent shrinkage trends in some southern counties have slightly moderated growth differentials.[50][51] Ethnically, both regions are dominated by the Han Chinese, who comprise over 91% of China's population nationally, with regional variations stemming from historical assimilations and migrations rather than stark divides.[52] In northern China, minorities such as Mongols (around 6 million, primarily in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region), Manchus (over 10 million, concentrated in Liaoning and Heilongjiang), and Koreans (in Jilin) constitute notable shares in specific provinces, often exceeding 10-20% locally but averaging under 10% regionally due to Han majorities.[53] Southern China hosts greater overall minority diversity, including the Zhuang (19.6 million, mainly in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Miao (11 million across Guizhou and Yunnan), and Yi (9 million in Sichuan and Yunnan), reflecting concentrations in southwestern highlands and river basins where terrain preserved distinct groups amid Han expansion.[54] These minorities, totaling about 8.5% of the national population or roughly 120 million in 2020, cluster more in peripheral autonomous areas than core Han heartlands, with southern provinces like Yunnan exhibiting up to 25% non-Han composition compared to northern averages below 15%.[55] Such patterns arise from geography—northern steppes favoring pastoral nomads like Mongols, southern tropics enabling settled hill tribes—rather than uniform north-south polarization, as Han intermixing has homogenized urban centers across both.[54]Linguistic and Dialectal Differences

Northern China is predominantly characterized by varieties of Mandarin Chinese, which belong to the northern branch of Sinitic languages and exhibit a dialect continuum with substantial mutual intelligibility among speakers.[56] Mandarin dialects, standardized as Standard Chinese based on the Beijing dialect since the early 20th century, feature four main tones and simplified phonology influenced by historical nomadic invasions and vast northern plains facilitating linguistic convergence.[57] These varieties, including Northeastern, Hebei, and Shaanxi subdialects, cover regions from the Yellow River basin northward, with over 70% of China's population using Mandarin forms as their primary tongue.[58] In contrast, southern China displays far greater linguistic diversity, encompassing non-Mandarin Sinitic branches such as Yue (including Cantonese), Wu (Shanghainese), Min (Hokkien and Teochew), Gan, Xiang, and Hakka, which often lack mutual intelligibility with Mandarin or each other due to geographical isolation from mountainous terrain and river systems.[59] Southern varieties typically retain more tones—up to nine in some Min dialects—and archaic phonological and lexical features closer to Middle Chinese, as evidenced by comparative reconstructions showing less erosion from northern substrate influences.[60] For instance, Cantonese (Yue) spoken in Guangdong and Hong Kong preserves six to nine tones and final consonants lost in Mandarin, rendering spoken communication between northern and southern speakers effectively impossible without shared written characters.[56] Experimental studies confirm asymmetric mutual intelligibility, with Mandarin speakers understanding southern varieties at rates below 20% in functional tests, while southern speakers fare slightly better with Mandarin due to its national standardization via education and media since 1956.[61] This divide stems from causal factors like northern political dominance promoting Mandarin as the lingua franca, contrasted with southern substrate languages and migration barriers preserving diversity; linguists estimate over 200 mutually unintelligible Sinitic varieties overall, with southern regions hosting the majority.[62]| Major Sinitic Group | Primary Regions | Key Features | Approximate Speakers (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (Northern) | North China Plain, Northeast | 4 tones, erhua; high intelligibility | 800+[56] |

| Yue (Cantonese) | Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong | 6-9 tones, preserved stops | 60-80[56] |

| Wu (Shanghainese) | Jiangsu, Zhejiang | 5-8 tones, complex initials | 70-80[57] |

| Min | Fujian, Taiwan, Hainan | 7+ tones, nasal finals | 50-75[56] |

| Hakka | Scattered south, Jiangxi | 6 tones, conservative vocabulary | 30-40[57] |

Genetic, Anthropometric, and Health-Related Traits

Genetic studies of Han Chinese populations indicate a north-south cline in allele frequencies, with the greatest differentiation observed between northern Han Chinese (NHC) and southern Han Chinese (SHC), reflecting historical admixture with northern steppe populations in the north and Austroasiatic or Tai-Kadai groups in the south.[63] Principal component analysis clusters northern and southern Han separately, with northern groups showing closer affinity to Altaic-speaking populations and southern groups to indigenous southern ethnicities.[64] Y-chromosome and autosomal SNP data confirm this structure, attributing it to ancient migrations and limited gene flow across the Qinling-Huaihe line, though overall Han genetic homogeneity remains high compared to ethnic minorities.[65][66] Anthropometric surveys reveal clinal variation, with adults from northern provinces averaging taller stature and greater body mass than those from southern provinces; for instance, males in northern regions exceed 175 cm on average, while southern counterparts average closer to 170 cm, a pattern persisting after controlling for socioeconomic factors.[67] Body mass index (BMI) follows a similar gradient, with northern Chinese exhibiting means over 2 kg/m² higher than southerners, correlating with regional dietary staples like wheat-based foods promoting higher caloric density.[68] These differences align with Bergmann's rule, where colder northern climates favor larger body sizes for thermoregulation, compounded by genetic and nutritional influences.[67] Health outcomes diverge regionally, with northern populations facing elevated risks of hypertension, where systolic blood pressure averages 4-5 mmHg higher than in the south, independent of age and sex.[69] Obesity prevalence is approximately 10% higher in the north, linked to diets high in sodium and animal fats, fewer vegetables, and sedentary urbanization trends.[70] Cardiovascular disease mortality and stroke burden show a north-higher-than-south pattern, with genetic predisposition scores for stroke increasing northward (p < 0.0001 across provinces), exacerbated by environmental factors like temperature extremes.[71][72] Southern regions, conversely, report lower multimorbidity rates but higher parasitic disease burdens historically, though infectious risks have declined post-1950s eradication campaigns.[73] These disparities underscore causal interactions between genetics, diet, and geography, rather than isolated factors.[74]Cultural and Social Differences

Agricultural Foundations and Rice-Wheat Theory

Northern China's agriculture historically centered on dryland farming suited to its semi-arid climate and loess soils along the Yellow River basin, with foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) as primary staples domesticated around 10,000–8,000 years ago.[75][76] Wheat (Triticum aestivum), introduced from Central Asia approximately 4,000–5,000 years ago, supplemented millets as a winter crop, enabling double-cropping systems but requiring less irrigation than southern practices.[77] These crops supported denser populations in fertile plains but were vulnerable to droughts and floods, fostering resilient, individualistic farming units.[78] In contrast, southern China's wetter subtropical climate in the Yangtze River basin and beyond facilitated irrigated rice (Oryza sativa) cultivation, domesticated around 10,000 years ago, which demands intensive labor for transplanting, weeding, and shared irrigation networks across paddies.[79][80] Rice farming yielded higher caloric returns per unit area—up to twice that of wheat under optimal conditions—but required coordinated water management and family labor cooperation, shaping larger, interdependent rural communities.[5] This agricultural divide, persisting into modern times despite mechanization, underpins regional economic patterns, with northern wheat-millet zones focusing on extensive grains and southern rice areas on labor-intensive paddies supplemented by aquaculture.[81] The rice-wheat theory posits that these divergent farming legacies causally influence cultural psychology, with rice agriculture promoting collectivism through its demands for interdependence, while wheat farming encourages individualism via more autonomous practices. Proposed by Thomas Talhelm and colleagues in a 2014 Science study analyzing data from over 1,100 Chinese participants, the theory found that individuals from historically rice-dependent provinces scored higher on measures of holistic thinking and relational identity, contrasting with analytic, independent orientations in wheat regions, even controlling for confounders like GDP and urbanization.[5] Supporting evidence includes observational behaviors, such as southern Chinese in Starbucks rearranging chairs more collectively than northerners, and tighter social norms in rice areas correlating with historical farming intensity.[82][83] Quasi-experimental data from China's 1950s land reforms, which randomly assigned families to rice or wheat plots, further bolsters causality: those allocated to rice exhibited greater collectivism, reduced self-enhancement bias, and stronger in-group favoritism toward friends over strangers compared to wheat assignees, with effects persisting across generations.[84][85] Critics note potential confounds from migration or policy, yet the pattern holds in implicit association tests and cross-regional comparisons, suggesting agriculture as a deep causal driver of north-south psychological divides beyond mere correlation.[86] This framework explains variances in traits like emotional perception accuracy and conformity, with rice cultures showing heightened sensitivity to relational cues.[87] While not deterministic, the theory underscores how ecological pressures via agriculture embed enduring cultural adaptations.[88]Cuisine, Customs, and Daily Life

Northern Chinese cuisine predominantly features wheat-based staples such as noodles, dumplings, steamed buns (mantou), and flatbreads, reflecting the region's historical reliance on dry-field grains like wheat and millet due to cooler, arid climates unsuitable for paddy rice.[89] [90] Dishes often emphasize saltier, heavier, and oilier preparations with flavors derived from soy sauce, vinegar, and fermented pastes, providing denser caloric intake for harsher winters and labor-intensive farming.[91] In contrast, southern Chinese cuisine centers on rice as the primary staple, including steamed rice, rice noodles, and congee, enabled by the humid subtropical environment supporting wet-rice paddy cultivation that demands intensive irrigation and communal labor.[92] Southern styles vary regionally—such as spicier Sichuan fare with chili and Sichuan peppercorns or milder, sweeter Jiangsu and Zhejiang dishes highlighting fresh seafood and subtle sweetness—but generally incorporate lighter stir-fries, dim sum, and soups that align with warmer climates and abundant water resources.[93] [94] [95] Customs in northern China often reflect a more individualistic orientation, with social interactions characterized by directness, outspokenness, and brusque communication styles, potentially rooted in wheat farming's lower coordination needs compared to rice agriculture's interdependence.[96] Family structures emphasize nuclear units over extended clans, and traditions like Lunar New Year celebrations feature hearty wheat-based feasts and communal gatherings focused on familial hierarchy.[97] Southern customs, influenced by rice cultivation's historical requirements for collective irrigation and labor sharing, promote greater collectivism, with stronger lineage systems, clan-based villages, and interpersonal norms prioritizing harmony, perspective-taking, and avoidance of direct conflict.[4] [84] Practices such as ancestral worship and multi-generational households are more prevalent in the south, where cooperative decision-making in festivals like the Dragon Boat Festival underscores group cohesion over individual assertion.[98] These patterns persist despite modernization, as evidenced by regional variations in wise reasoning during disputes, where southerners demonstrate higher intellectual humility and recognition of multiple perspectives.[98] Daily life in northern China tends toward analytic, independent routines, with empirical observations showing greater willingness to alter shared environments unilaterally—such as rearranging public seating for personal convenience—mirroring wheat farming's self-reliant practices.[82] Urban northerners often engage in straightforward social exchanges and abstraction-oriented leisure, like intellectual debates or sports emphasizing competition, while rural life revolves around seasonal wheat harvests yielding fewer but larger yields with less daily coordination.[99] Southern daily life exhibits more holistic, interdependent habits, including collaborative neighborhood activities and conflict resolution favoring compromise, as rice farming historically necessitated year-round group efforts for flooding fields and pest control.[88] In contemporary settings, southerners report higher reliance on social networks for problem-solving, with studies confirming elevated collectivistic behaviors in routine interactions across provinces like Guangdong versus Hebei.[100] These differences, while moderated by urbanization, trace causally to agricultural legacies, with rice regions fostering tighter social bonds and wheat areas promoting autonomy, as quasi-experimental assignments to rice farming correlate with increased collectivism.[84]Behavioral Stereotypes and Empirical Evidence

Common stereotypes portray northern Chinese as more straightforward, assertive, and physically robust, often associating them with higher alcohol consumption and a preference for direct confrontation, while southern Chinese are depicted as more reserved, shrewd in business dealings, and emphasizing relational harmony and indirect communication.[100][4] Empirical research, particularly studies rooted in the rice-wheat theory, provides evidence for cultural differences in cognition and social orientation attributable to historical agricultural practices. Northern wheat farming, which allowed more individual autonomy, correlates with greater individualism and analytic thinking, whereas southern rice farming demanded intensive irrigation cooperation, fostering interdependence and holistic cognition. A 2018 observational study across 43 Starbucks locations in six Chinese cities found northern participants more likely to rearrange obstructing chairs (adapting environment to self, 18% vs. 4% in south), aligning with individualistic tendencies, while southerners adapted by squeezing through (self to environment).[82][101] Further support comes from psychological assessments: southerners from rice regions exhibit higher wise reasoning in interpersonal conflicts, scoring 12-20% better on measures of recognizing situational limits and multiple perspectives compared to northern wheat-region counterparts in experiments involving friend or colleague disputes. A 2024 quasi-experimental analysis of China's 1950s land reform, which randomly assigned rice vs. wheat farming to villages, confirmed causality, with rice-assigned groups showing 10-15% less individualism, greater loyalty to in-groups over strangers, and more relational (vs. rule-based) thinking patterns persisting into modern generations.[98][84] Alcohol consumption data reinforces northern stereotypes, with epidemiological surveys indicating higher prevalence and volume in northern provinces; for instance, rural men in northern areas report 20-30% greater weekly intake than southern counterparts, linked to cultural norms of group toasting in wheat regions. Evidence on other behaviors, such as crime rates, remains sparse and inconclusive, with national homicide rates low (0.5 per 100,000 in 2020) but no robust regional breakdowns isolating north-south disparities after controlling for urbanization.[102][103][104]Economic Patterns and Disparities

Traditional and Agricultural Economies

Northern China's traditional economy centered on dryland farming of wheat, millet, and sorghum in the Yellow River basin, where rainfall-dependent cultivation predominated due to the region's semi-arid loess soils and proneness to droughts and floods.[4] Winter wheat was the staple, sown in autumn and harvested in summer, yielding approximately 1,000-1,500 kg per hectare in pre-modern eras before hybrid varieties, limited by single-season cropping and soil erosion.[105] This system supported subsistence-oriented households with larger land holdings per capita, incorporating some pastoralism with livestock like oxen for plowing, but generated lower surpluses, fostering periodic famines such as those in the 1870s that displaced millions southward.[106] In contrast, southern China's agricultural economy relied on wet-rice paddy systems along the Yangtze River and Pearl River deltas, necessitating extensive irrigation networks, terracing, and communal labor coordination for water management across fields.[107] Rice cultivation, often double-cropped (early and late varieties), demanded roughly twice the labor input of wheat farming—up to 3,000 hours per hectare annually—yet delivered higher land productivity, with historical yields reaching 2,000-4,000 kg per hectare by the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), enabling population densities up to three times those in the north.[108] This intensity arose from rice's biological traits, including flood tolerance and nitrogen-fixing associates, which maximized output on smaller, fragmented plots, generating surpluses that fueled proto-commercial activities like silk production and riverine trade by the Ming era (1368-1644 CE).[88] These disparities shaped divergent economic structures: northern farming emphasized self-reliant, individualistic operations with minimal interdependence, yielding modest grain taxes that strained imperial revenues during crises, while southern rice economies promoted labor-sharing institutions and higher per-unit outputs, underpinning urban centers like Hangzhou and contributing to China's overall GDP where agriculture comprised 80-90% pre-1800.[109] Empirical reconstructions indicate southern per capita agricultural output exceeded northern by 20-50% in caloric terms during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912 CE), though vulnerable to typhoons and siltation, with rice-wheat regional borders persisting as a proxy for these productivity gradients.[110]Industrialization, Urbanization, and Sectoral Focus

Following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, early industrialization under central planning prioritized heavy industry in northern regions, capitalizing on pre-existing infrastructure from the Japanese occupation of Manchuria (1931–1945) and abundant coal reserves in provinces like Shanxi and Inner Mongolia.[111] This focus built steel mills, machinery plants, and chemical facilities in the Northeast (e.g., Anshan Iron and Steel), where output grew rapidly in the 1950s due to Soviet technical aid and resource proximity, contributing to northern China's secondary sector comprising over 40% of its GDP by the late 1950s.[112] Southern China, by contrast, lagged in heavy industry, with development centered on light manufacturing such as textiles in Shanghai and agriculture-linked processing in the Yangtze Delta, as the region's rice-based economy and limited fossil fuels directed resources toward consumer goods rather than capital-intensive projects.[3] The 1978 economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping shifted dynamics decisively toward the south, establishing Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Guangdong and Fujian provinces to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) for export-oriented manufacturing.[113] Cities like Shenzhen transformed from rural areas into industrial powerhouses, with manufacturing—particularly electronics and assembly—driving GDP growth rates exceeding 10% annually in southern coastal provinces through the 1990s and 2000s.[114] Northern industrialization, reliant on state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in declining sectors like coal and steel, faced overcapacity and inefficiency; by 2019, the north's share of national industrial production had fallen to less than half that of the south, exacerbated by environmental regulations curbing high-pollution activities.[115] Urbanization rates reflect these industrial divergences, with southern China experiencing faster rural-to-urban migration fueled by labor-intensive factories and proximity to global markets. By 2023, permanent urbanization in southern provinces like Guangdong reached approximately 75%, compared to around 60% in northern inland areas like Henan and Shanxi, contributing to megacity clusters in the Pearl River Delta housing over 80 million residents.[116] Northern urbanization, tied to resource extraction and SOE towns, grew more slowly, with cities like Shenyang and Harbin stagnating amid industrial restructuring; national urbanization hit 66.2% in 2023, but southern pull factors accounted for much of the 1.5% annual increase in urban population.[117] Policies like the 2000s "Develop the West" initiative aimed to boost northern urban infrastructure, yet migration flows predominantly southward persisted due to higher wage differentials in manufacturing hubs.[118] Sectorally, southern China's economy emphasizes advanced manufacturing and services, with the secondary sector (39% of GDP in 2023) dominated by high-value exports like semiconductors in the Yangtze River Delta, while tertiary industries—finance, logistics, and tech—comprise over 55% in hubs like Shanghai.[115] Northern regions retain a heavier focus on extractive industries, with mining and utilities forming 15–20% of output in coal-dependent provinces, and secondary sectors like metallurgy declining to under 35% of GDP amid a shift toward renewables.[119] This north-south sectoral imbalance widened post-2012, as southern innovation clusters captured FDI inflows totaling $200 billion annually by 2020, versus northern reliance on domestic stimulus that yielded lower productivity gains.[114]Contemporary Gaps, Policies, and Recent Developments

Economic disparities between northern and southern China have widened in recent years, with southern coastal provinces outperforming northern and northeastern regions in GDP growth and per capita income due to stronger private sector involvement, export manufacturing, and technological innovation, contrasted against the north's heavier dependence on state-owned enterprises and resource-based industries vulnerable to global transitions like decarbonization.[120][121] In 2023, Jiangsu Province in the south recorded a GDP per capita of 150,487 RMB (approximately 21,200 USD), surpassing the national average, while northeastern provinces such as Heilongjiang and Liaoning lagged below this benchmark, contributing to elevated credit risks and slower industrial upgrading in the north.[122][121] The national GDP per capita reached 95,749 RMB (about 13,400 USD) in 2024, highlighting persistent regional imbalances despite overall growth.[123] To mitigate these gaps, the Chinese central government has pursued targeted policies, including infrastructure development, education enhancement, and industrial relocation to stimulate northern economies.[124] A key initiative is the Northeast Area Revitalization Plan, intensified under the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), which focuses on reforming state-owned enterprises, attracting foreign investment, and fostering new industries like advanced manufacturing and digital economy to transition from rust-belt status.[125][126] In February 2025, President Xi Jinping emphasized comprehensive deepening of reforms and opening up as essential for the region's full revitalization, with measures to improve connectivity and reduce south-north divides through projects like high-speed rail and broadband expansion.[127][128] Recent developments indicate mixed progress amid broader economic challenges. China's GDP growth slowed to 4.8% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2025, with northern regions experiencing amplified pressures from property market deleveraging and declining demand for traditional sectors, potentially exacerbating the divide as southern tech hubs like Guangdong maintain momentum through exports and FDI.[129][130] Efforts under the revitalization strategy have yielded some gains, such as increased foreign interest in northeastern ice-and-snow economies and industrial parks, but structural issues like overcapacity and demographic decline continue to hinder convergence.[131] Policymakers anticipate further interventions in the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan to prioritize rural and regional development, though widening credit disparities suggest persistent vulnerabilities in the north.[132][121]Political and Governance Aspects

Historical Power Centers and Regional Influences

The cradle of Chinese civilization and early political power lay in northern China, particularly along the Yellow River basin, where the foundational dynasties established their authority. The semi-legendary Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE) and the subsequent Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) maintained capitals in the north, such as near modern Anyang in Henan province, facilitating control over fertile alluvial plains and early bronze-age societies.[37] The Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) further entrenched northern dominance with capitals at Haojing (near modern Xi'an) and later Luoyang, from which it exerted feudal oversight over vassal states primarily in the north-central plains.[37] This geographic focus stemmed from the region's suitability for millet-based agriculture and defense against nomadic incursions from the steppes, shaping a governance model emphasizing centralized ritual authority and military mobilization.[133] Unifying imperial dynasties reinforced northern China as the primary power center, with capitals strategically positioned for continental defense and resource extraction. The Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) unified the realm under Emperor Qin Shi Huang from Xianyang near Xi'an, standardizing administration and infrastructure to consolidate northern heartland control.[134] The Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) alternated between Chang'an (modern Xi'an) and Luoyang as capitals, both in the north, enabling expansion against Xiongnu nomads and bureaucratic centralization that influenced subsequent governance structures.[134] Later, the Sui (581–618 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) dynasties reverted to Chang'an, leveraging its position to manage northern frontiers and canal networks linking to southern grain supplies, underscoring how northern loci facilitated empire-wide coercion and taxation.[134] Periods of division, such as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589 CE), saw northern regimes like the Northern Wei (386–535 CE) with capitals at Datong and Luoyang counter non-Han influences through sinicization policies, while southern polities in Jiankang (modern Nanjing) remained fragmented and economically oriented but politically marginal.[135][133] Southern China occasionally hosted imperial capitals during northern vulnerabilities, yet these shifts highlighted rather than overturned northern primacy. The Northern Song dynasty (960–1127 CE) held Kaifeng in the north until Jurchen invasions prompted relocation to Hangzhou for the Southern Song (1127–1279 CE), where maritime trade bolstered finances but diluted military resolve against steppe threats.[37] The Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE) initially established Nanjing as capital in 1368, reflecting southern rebel origins under Zhu Yuanzhang, but relocated to Beijing in 1421 to address Mongol resurgence, restoring northern strategic centrality.[134] The Qing dynasty (1644–1912 CE) maintained Beijing (Dadu from Yuan times), prioritizing northern Manchu heritage and frontier security.[37] These exceptions often arose from northern collapse, with southern centers proving unsustainable for full reunification due to logistical challenges in projecting power northward. Regional influences manifested in divergent governance styles, with the north fostering militaristic, hierarchical systems attuned to nomadic pressures and vast plains logistics, while the south emphasized bureaucratic refinement and hydraulic engineering suited to rice paddies and river deltas. Northern regimes, confronting equine warfare from the steppes, integrated cavalry tactics and frontier garrisons, as seen in Tang expansions, promoting a realpolitik of alliances and coercion over southern preferences for Confucian literati exams and mercantile taxation.[133] This north-south asymmetry persisted, with southern wealth funding northern capitals via the Grand Canal (completed 605 CE under Sui), yet engendering tensions where southern elites resisted northern fiscal demands, contributing to dynastic cycles of rebellion and reconquest.[134] Empirical patterns indicate that unifying dynasties originated or stabilized in the north 80% of the time across major eras, reflecting causal advantages in defensibility and cultural continuity from archaic states.[37]Central Control vs. Local Autonomy

China's political system maintains strong central control through the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which appoints key local officials and enforces ideological conformity, yet fiscal decentralization since the late 1970s has granted subnational governments significant autonomy in economic decision-making and resource allocation.[136] This hybrid structure allows local governments to retain a substantial portion of tax revenues—often exceeding 80% of total expenditures—enabling experimentation with policies tailored to regional conditions, though ultimate authority resides with Beijing.[137] In practice, this has fostered tensions between central directives and local incentives, particularly in implementation of national priorities like poverty alleviation or environmental regulations, where local officials balance compliance with growth targets.[138] Regional differences manifest starkly between northern and southern provinces, with the south exhibiting greater de facto autonomy due to its economic dynamism and proximity to global markets. Southern coastal areas, such as Guangdong and Zhejiang, capitalized on decentralization by establishing special economic zones in the 1980s, attracting foreign direct investment and pioneering private enterprise models that influenced national reforms.[139] Empirical data indicate that fiscal decentralization has yielded higher development gains in southern regions, with a coefficient of 0.130 in econometric models linking autonomy to high-quality economic growth, compared to negligible effects in central and northern areas.[140] Northern provinces, historically centered on state-owned heavy industries like steel and coal in Hebei and Shanxi, have remained more aligned with central planning legacies, resulting in slower adaptation to market-oriented policies and higher dependence on Beijing's subsidies.[141] This north-south divergence has exacerbated implementation gaps, as southern local governments prioritize revenue-generating infrastructure and export-led growth, often at the expense of uniform national standards, while northern counterparts face constraints from resource scarcity and bureaucratic inertia.[142] Decentralization contributed to widening interprovincial disparities, with southern per capita fiscal expenditures outpacing northern ones by factors linked to local retention rates post-1994 tax reforms.[141] However, under Xi Jinping's leadership since 2012, recentralization efforts—such as intensified anti-corruption campaigns and direct CCP oversight of local finances—have curtailed this autonomy, compelling southern innovators to align more closely with central mandates on issues like debt control and common prosperity, thereby mitigating but not eliminating regional variations in governance flexibility.[143]Regionalism Debates and National Unity Challenges

![China_linguistic_map.jpg][float-right] Regionalism debates in China highlight tensions between entrenched north-south cultural, linguistic, and economic differences and the central government's emphasis on national unity under a unitary state structure. Southern regions, characterized by diverse dialects such as Cantonese and stronger local identities tied to historical migration patterns and rice-based agrarian traditions, often exhibit resistance to full linguistic assimilation into standard Mandarin, fostering debates on the balance between regional cultural preservation and national standardization.[4] These differences, rooted in geography and historical invasions more prevalent in the north, contribute to perceptions of southern cooperation versus northern individualism, complicating uniform national narratives.[4] Economic disparities exacerbate these debates, with southern provinces driving over 80% of China's exports and demonstrating faster growth in industrial and tertiary sectors compared to the north as of 2020.[115] Interregional inequality surged 798% from 1952 to 2013 per Theil index measures, peaking amid post-1978 reforms that favored coastal south, leading to northern population stagnation (2% growth 2010-2020) versus southern expansion (8.5%).[144][115] Scholars argue such gaps, including R&D spending disparities widening to 3-4 times by the 2020s, risk social tensions if unaddressed, prompting calls for decentralized policy flexibility to leverage regional strengths like southern market orientation against northern bureaucratic inertia.[115][144] Politically, debates contrast unitarism—China's official framework rejecting federalism—with de facto federalist elements observed in local experimentation during reforms.[145] Proponents of greater regional autonomy, including some overseas Chinese scholars, contend that accommodating north-south variances through enhanced local governance could mitigate fragmentation risks without secession, as seen in historical tensions where southern openness historically clashed with northern centrality.[146][147] However, the Chinese Communist Party maintains strict central control, viewing federalism as a threat to sovereignty, and promotes regional ethnic autonomy laws since 1954 primarily for minorities rather than Han regionalism.[148] National unity challenges arise from these divides potentially undermining stability, as inequality conflicts with egalitarian ideology and fuels migration strains, with northerners comprising significant portions of southern populations like 67% non-locals in Sanya by 2020.[144][115] Policies such as the 1999 Western Development initiative and post-2008 fiscal transfers have reduced interprovincial gaps by 13% in hukou-adjusted measures, yet persistent north-south imbalances persist, raising concerns over long-term cohesion absent adaptive decentralization.[144] While overt separatism remains minimal among Han populations, unmitigated resentments could amplify under economic slowdowns, underscoring the causal link between regional disparities and unity pressures.[144][149]References

- https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:Qinling_Huaihe_Line