Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Treaty of Rome

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

| |

| Type | Founding treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 25 March 1957 |

| Location | Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy |

| Effective | 1 January 1958 |

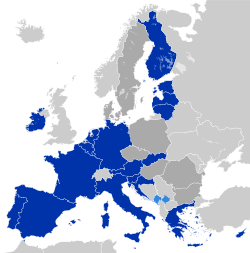

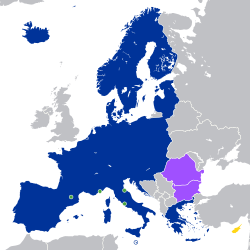

| Parties | EU member states |

| Depositary | Government of Italy |

| Full text | |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signed on 25 March 1957 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany, and it came into force on 1 January 1958. Originally the "Treaty establishing the European Economic Community", and now continuing under the name "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union", it remains one of the two most important treaties in what is now the European Union (EU).

The treaty proposed the progressive reduction of customs duties and the establishment of a customs union. It proposed to create a common market for goods, labour, services, and capital across member states. It also proposed the creation of a Common Agriculture Policy, a Common Transport Policy and a European Social Fund and established the European Commission.

The treaty has been amended on several occasions since 1957. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 removed the word "economic" from the Treaty of Rome's official title, and in 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon renamed it the "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union".

History

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1951, the Treaty of Paris was signed, creating the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The Treaty of Paris was an international treaty based on international law, designed to help reconstruct the economies of the European continent, prevent war in Europe and ensure a lasting peace.

The original idea was conceived by Jean Monnet, a senior French civil servant and it was announced by Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister, in a declaration on 9 May 1950. The aim was to pool Franco-West German coal and steel production, because the two raw materials were the basis of the industry (including war industry) and power of the two countries. The proposed plan was that Franco-West German coal and steel production would be placed under a common High Authority within the framework of an organisation that would be open for participation to other European countries. The underlying political objective of the European Coal and Steel Community was to strengthen Franco-German cooperation and banish the possibility of war.

France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands began negotiating the treaty. The Treaty Establishing the ECSC was signed in Paris on 18 April 1951, and entered into force on 24 July 1952. The Treaty expired on 23 July 2002, after fifty years, as was foreseen. The common market opened on 10 February 1953 for coal, iron ore and scrap, and on 1 May 1953 for steel.

Partly in the aim of creating a United States of Europe, two further Communities were proposed, again by the French. A European Defence Community (EDC) and a European Political Community (EPC). While the treaty for the latter was being drawn up by the Common Assembly, the ECSC parliamentary chamber, the EDC was rejected by the French Parliament. President Jean Monnet, a leading figure behind the Communities, resigned from the High Authority in protest and began work on alternative Communities, based on economic integration rather than political integration.[1]

As a result of the energy crises, the Common Assembly proposed extending the powers of the ECSC to cover other sources of energy. However, Monnet desired a separate Community to cover nuclear power, and Louis Armand was put in charge of a study into the prospects of nuclear energy use in Europe. The report concluded that further nuclear development was needed, in order to fill the deficit left by the exhaustion of coal deposits and to reduce dependence on oil producers. The Benelux states and West Germany were also keen on creating a general common market; however, this was opposed by France owing to its protectionist policy, and Monnet thought it too large and difficult a task. In the end, Monnet proposed creating both as separate Communities to attempt to satisfy all interests.[2] As a result of the Messina Conference of 1955, Paul-Henri Spaak was appointed as chairman of a preparatory committee, the Spaak Committee, charged with the preparation of a report on the creation of a common European market. Both the Spaak report and the Treaty of Rome were drafted by Pierre Uri, a close collaborator of Monnet.

Move towards a common market

[edit]The Spaak Report[3] drawn up by the Spaak Committee provided the basis for further progress and was accepted at the Venice Conference (29 and 30 May 1956) where the decision was taken to organise an Intergovernmental Conference. The report formed the cornerstone of the Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom at Val Duchesse in 1956.

The outcome of the conference was that the new Communities would share the Common Assembly (now the Parliamentary Assembly) with the ECSC, as they would the European Court of Justice. However, they would not share the ECSC's Council or High Authority. The two new High Authorities would be called Commissions, from a reduction in their powers. France was reluctant to agree to more supranational powers; hence, the new Commissions would have only basic powers, and important decisions would have to be approved by the Council (of national Ministers), which now adopted majority voting.[4] Euratom fostered co-operation in the nuclear field, at the time a very popular area, and the European Economic Community was to create a full customs union between members.[5][6]

In 1965, France's president Charles de Gaulle decided to recall French representatives from dealing with the Council of Ministers, greatly crippling the EEC's operations. This was known as the "Empty Chair Crisis."[7] To resolve this, the members agreed to the Luxembourg Compromise, in which veto power was given to members of the EC on decisions.[8] The countries of the European Community held a meeting in The Hague in 1969. At this summit, they collectively ordered an increase to the European Parliament's budget while also committing towards a shift away from national economic policy to greater international policy. Following this agreement, two new European Structural Investment Funds were created, which were the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund. These focused on the reallocation of investment funds towards the development of the economies of the member states.[9]

Signing

[edit]

The conference led to the signing on 25 March 1957, of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community and the Euratom Treaty at the Palazzo dei Conservatori on Capitoline Hill in Rome. 25 March 1957 was also the Catholic feast day of the Annunciation of Mary.

In March 2007, the BBC's Today radio programme reported that delays in printing the treaty meant that the document signed by the European leaders as the Treaty of Rome consisted of blank pages between its frontispiece and page for the signatures.[10][11][12]

Anniversary commemorations

[edit]Major anniversaries of the signing of the Treaty of Rome have been commemorated in numerous ways.

Commemorative coins

[edit]Commemorative coins have been struck by numerous European countries, notably at the 30th and 50th anniversaries (1987 and 2007 respectively).

2007 celebrations in Berlin

[edit]In 2007, celebrations culminated in Berlin with the Berlin declaration preparing the Lisbon Treaty.

2017 celebrations in Rome

[edit]

In 2017, Rome was the centre of multiple official[14][15][16] and popular celebrations.[17][18] Street demonstrations were largely in favour of European unity and integration, according to several news sources.[19][20][21][22]

Historical assessment

[edit]According to the historian Tony Judt, the Treaty of Rome did not represent a fundamental turning point in the history of European integration:

It is important not to overstate the importance of the Rome Treaty. It represented for the most part a declaration of future good intentions...Most of the text constituted a framework for instituting procedures designed to establish and enforce future regulations. The only truly significant innovation – the setting up under Article 177 of a European Court of Justice to which national courts would submit cases for final adjudication – would prove immensely important in later decades but passed largely unnoticed at the time.[23]

Timeline

[edit]Since the end of World War II, most sovereign European countries have entered into treaties and thereby co-operated and harmonised policies (or pooled sovereignty) in an increasing number of areas, in the European integration project or the construction of Europe (French: la construction européenne). The following timeline outlines the legal inception of the European Union (EU)—the principal framework for this unification. The EU inherited many of its present organizations, institutions, and responsibilities from the European Communities (EC), which were founded in the 1950s in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration.

| Legend: S: signing F: entry into force T: termination E: expiry de facto supersession Rel. w/ EC/EU framework: de facto inside outside |

[Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

| (Pillar I) | ||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or EURATOM) | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | European Community (EC) | |||||||||||||||||

| TREVI | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA, pillar III) | |||||||||||||||||

| [Cont.] | Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC, pillar III) | |||||||||||||||||

Anglo-French alliance |

[Defence arm handed to NATO] | European Political Co-operation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, pillar II) | |||||||||||||||

| [Tasks defined following the WEU's 1984 reactivation handed to the EU] | ||||||||||||||||||

| [Social, cultural tasks handed to CoE] | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||||

Entente Cordiale

S: 8 April 1904 |

Davignon report

S: 27 October 1970 |

European Council conclusions

S: 2 December 1975 |

||||||||||||||||

- ^ a b c d e Although not EU treaties per se, these treaties affected the development of the EU defence arm, a main part of the CFSP. The Franco-British alliance established by the Dunkirk Treaty was de facto superseded by WU. The CFSP pillar was bolstered by some of the security structures that had been established within the remit of the 1955 Modified Brussels Treaty (MBT). The Brussels Treaty was terminated in 2011, consequently dissolving the WEU, as the mutual defence clause that the Lisbon Treaty provided for EU was considered to render the WEU superfluous. The EU thus de facto superseded the WEU.

- ^ Plans to establish a European Political Community (EPC) were shelved following the French failure to ratify the Treaty establishing the European Defence Community (EDC). The EPC would have combined the ECSC and the EDC.

- ^ The European Communities obtained common institutions and a shared legal personality (i.e. ability to e.g. sign treaties in their own right).

- ^ The treaties of Maastricht and Rome form the EU's legal basis, and are also referred to as the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), respectively. They are amended by secondary treaties.

- ^ Between the EU's founding in 1993 and consolidation in 2009, the union consisted of three pillars, the first of which were the European Communities. The other two pillars consisted of additional areas of cooperation that had been added to the EU's remit.

- ^ The consolidation meant that the EU inherited the European Communities' legal personality and that the pillar system was abolished, resulting in the EU framework as such covering all policy areas. Executive/legislative power in each area was instead determined by a distribution of competencies between EU institutions and member states. This distribution, as well as treaty provisions for policy areas in which unanimity is required and qualified majority voting is possible, reflects the depth of EU integration as well as the EU's partly supranational and partly intergovernmental nature.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Raymond F. Mikesell, The Lessons of Benelux and the European Coal and Steel Community for the European Economic Community, The American Economic Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Seventieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May 1958), pp. 428–441

- ^ 1957–1968 Successes and crises – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ^ The Brussels Report on the General Common Market (abridged, English translation of document commonly called the Spaak Report) – AEI (Archive of European Integration)

- ^ Drafting of the Rome Treaties – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ^ A European Atomic Energy Community – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ^ A European Customs Union – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ^ Ludlow, N (2006). De-commissioning the Empty Chair Crisis: The Community Institutions and the Crisis of 1965-6. London School of Economics.

- ^ "The Luxembourg Compromise - Historical Events in the European Integration Process (1945–2009) - CVCE Website". www.cvce.eu.

- ^ Cini, Michelle; Borragán, Nieves Pérez-Solórzano (17 January 2013). European Union Politics (4th ed.). OUP Oxford. pp. 12–24. ISBN 978-0-19-969475-4.

- ^ "What really happened when the Treaty of Rome was signed 50 years ago".

- ^ EU landmark document was 'blank pages'

- ^ "How divided Europe came together". 23 March 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ MFE (26 March 2017). "The "European" Colosseum created by federalists on the first page of Frankfurter Allgemeigne Sonntagszeitung! #MarchForEurope2017pic.twitter.com/8JW7o4usBb".

- ^ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Rome Declaration of the Leaders of 27 Member States and of the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission". europa.eu. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Speech by President Donald Tusk at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the Treaties of Rome – Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Speech by President Juncker at the 60th Anniversary of the Treaties of Rome celebration – A new chapter for our Union: shaping the future of EU 27". europa.eu. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Cortei Roma, il raduno dei federalisti. "L'Europa è anche pace, solidarietà e diritti"". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 25 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Celebrazioni Ue, in 5 mila al corteo europeista". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 25 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "A Rome, plusieurs milliers de manifestants défilent pour «un réveil de l'Europe»". Libération.fr (in French). Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Des milliers de manifestants en marge des 60 ans du traité de Rome". Le Monde.fr (in French). 25 March 2017. ISSN 1950-6244. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Pro-European, Anti-Populist Protesters March as EU Leaders Meet in Rome". Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Trattati di Roma, cortei e sit-in: la giornata in diretta" (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Judt, Tony (2007). Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. London: Pimlico. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-7126-6564-3.

External links

[edit]- Documents of Treaty of Rome's negotiations are at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- Documents of Treaty establishing the European Economic Community in EUR-Lex

- History of the Rome Treaties – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- Treaty establishing the European Economic Community – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- Happy Birthday EU — Union wide design competition to mark the 50th anniversary of the Treaty

- 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome – Official Site

Treaty of Rome

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Post-World War II Economic and Political Context

The end of World War II in Europe in May 1945 left the continent in economic ruin, with widespread destruction of infrastructure, factories, and transportation networks across Western Europe. Industrial production had plummeted, reaching as low as one-third of pre-war levels in countries like France and the Benelux nations, while in Germany, approximately 20% of the housing stock was obliterated, exacerbating homelessness and resource shortages. Shortages of food, fuel, and basic consumer goods intensified immediately after the fighting ceased, contributing to hyperinflation, black markets, and social unrest, as production chains remained disrupted and agricultural output lagged due to labor shortages and displaced populations.[8][9][10] Politically, Europe faced acute division and instability, as wartime alliances fractured into ideological confrontation between the democratic West and the communist East, formalized by conferences such as Yalta (February 1945) and Potsdam (July-August 1945) that partitioned Germany into occupation zones and foreshadowed the Iron Curtain. The Soviet Union's expansion into Eastern Europe, installing puppet regimes in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia by 1948, heightened fears in the West of communist subversion, evidenced by strikes and electoral gains for communist parties in France and Italy, where they polled over 20% in 1946 elections. This bipolar structure, coupled with the need to demobilize millions of troops and repatriate displaced persons—estimated at 12 million in Germany alone—created a volatile environment where national revanchism, particularly regarding German rearmament and border disputes, risked renewed conflict.[11][12] The United States responded with the Marshall Plan, announced on June 5, 1947, and implemented from April 1948, providing $13.3 billion in grants and loans (equivalent to over $150 billion today) to 16 Western European countries through 1952, which facilitated infrastructure rebuilding, stabilized currencies, and boosted industrial output by an average of 35% across recipients by 1951. This aid not only addressed immediate economic collapse but also served geopolitical aims, countering Soviet influence by tying recovery to multilateral cooperation and excluding communist states that declined participation, such as Czechoslovakia under pressure from Moscow. By fostering interdependence, particularly in coal and steel sectors vital for recovery, the plan laid groundwork for supranational mechanisms, as fragmented national policies risked protectionism and inefficient reconstruction amid competition from America's intact economy, which produced half the world's goods by 1945.[13][14][8]Early European Integration Efforts

The Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950, proposed by French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman, outlined the creation of a supranational authority to manage coal and steel production among European nations, with the explicit aim of rendering future Franco-German war "not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible" by integrating these war-critical industries.[15] This initiative, drafted in consultation with Jean Monnet, marked the initial concrete step toward economic interdependence as a foundation for lasting peace, shifting from national rivalries to pooled sovereignty in strategic sectors.[16] The proposal culminated in the Treaty of Paris, signed on 18 April 1951 by the six founding members—Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany)—establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC).[17] The treaty entered into force on 23 July 1952 after ratification, creating supranational institutions including a High Authority to oversee production, pricing, and trade in coal and steel, thereby eliminating tariffs and quotas among members while promoting joint investment and modernization.[17] The ECSC's success in fostering economic cooperation and Franco-German reconciliation demonstrated the viability of limited supranationalism, though it faced challenges such as national resistance to ceding control over heavy industries.[15] Subsequent efforts sought to extend integration beyond economics into defense and politics. The European Defence Community (EDC), proposed in the 1950 Pleven Plan amid the Korean War's escalation, envisioned a supranational army under integrated command to counter Soviet threats while avoiding full national rearmament, particularly of Germany; its treaty was signed in 1952 by the six ECSC states but failed ratification when the French National Assembly rejected it on 30 August 1954 by a vote of 280 to 280 after tie-breaking abstentions.[18] Linked to the EDC, the European Political Community (EPC) draft treaty aimed to create a federal-like structure with a common assembly and executive, but collapsed alongside the EDC due to sovereignty concerns, divergent national interests, and French fears of German military resurgence.[18] These setbacks highlighted the limits of rapid political union, redirecting momentum toward narrower economic mechanisms as a more feasible path forward.[18]Messina Conference and Preparatory Negotiations

The Messina Conference convened from 1 to 3 June 1955 in Messina, Sicily, hosted by Italian Foreign Minister Gaetano Martino, bringing together the foreign ministers of the six European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) member states: Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.[19] The meeting aimed to evaluate the ECSC's operations, which had demonstrated functional success since its 1952 establishment in fostering economic cooperation among former adversaries, and to explore avenues for broader European integration following the 1954 failure of the European Defence Community treaty.[19] Discussions drew heavily on a Benelux memorandum, authored primarily by Dutch Foreign Minister Johan Willem Beyen, advocating a customs union and sectoral integration in areas like transport and atomic energy to create a common market.[20] Despite initial French reservations over supranational authority—stemming from domestic political instability under the Fourth Republic—the conference produced the Messina Declaration on 3 June, endorsing the creation of a European Economic Community (EEC) focused on gradual establishment of a customs union, elimination of internal trade quotas, and common external tariffs, alongside a separate European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) for nuclear cooperation.[19] To advance these goals, the ministers established an ad hoc intergovernmental committee chaired by Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak, comprising high-level experts from each state, tasked with drafting concrete proposals within three to six months.[21] The committee's formation marked a pivotal shift from stalled post-ECSC initiatives, emphasizing pragmatic economic federation over ambitious political union.[22] The Spaak Committee, operational from July 1955, conducted intensive deliberations in Brussels and other venues, reconciling divergent national interests through technical working groups on trade liberalization, agriculture, and institutional design.[21] Its final report, presented on 21 April 1956, outlined the EEC's core architecture: a customs union progressing via transitional stages, supranational institutions including a commission and assembly, and coordination of economic policies, while separating Euratom to address French sensitivities on military applications of nuclear technology.[21] The report's recommendations, grounded in ECSC precedents of pooled sovereignty yielding economic gains, secured ministerial approval in May 1956, paving the way for the full intergovernmental conference in Brussels starting 26 June 1956.[23] These preparatory efforts underscored a consensus-driven process, with Spaak's diplomatic mediation instrumental in bridging gaps between German export-oriented liberalism and French protectionism.[20]Negotiation and Adoption

Intergovernmental Conference Dynamics

The Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom commenced on 26 June 1956 at the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Brussels, chaired by Paul-Henri Spaak, the Belgian foreign minister.[24] It operated through a Committee of Heads of Delegation, including Jean-Charles Snoy et d'Oppuers (Belgium), Carl Friedrich Ophüls (West Germany), Maurice Faure (France), Lodovico Benvenuti (Italy), Léon Schaus (Luxembourg), and Jan Linthorst Homan (the Netherlands).[24] Specialized subgroups handled the Common Market under Hans von der Groeben (Germany), Euratom under Pierre Guillaumat (France), and treaty drafting under Roberto Ducci (Italy), with input from ECSC High Authority experts, national officials, trade unions, and business groups.[24] The initial phase ran until 21 July 1956, with sessions resuming in September at Val Duchesse castle near Brussels, amid external pressures such as the Suez Crisis and Hungarian Uprising.[24] Negotiations proceeded from the framework of the Spaak Report, presented on 21 April 1956 and endorsed by foreign ministers at Venice on 29–30 May 1956, which proposed a customs union, free movement of goods and factors of production, and atomic energy cooperation.[21] Dynamics reflected tensions between supranational ambitions and national sovereignty, with France pushing for social policy harmonization to protect workers, separate institutions from the ECSC to avoid overlap, and an exceptional customs regime favoring its agriculture and overseas dependencies like Algeria.[24] West Germany emphasized industrial free trade and institutional efficiency, while smaller states like the Netherlands advocated balanced compromises. Euratom discussions advanced more smoothly than the Common Market, which stalled initially over methodological disputes and French domestic ratification concerns.[24] Major debates focused on associating overseas territories with the Common Market, resolved at a Paris meeting on 19–20 February 1957 through preferential access and a five-year investment fund of 581 million units of account; integrating social welfare harmonization, resulting in the European Social Fund's creation for mobility and standards; and Euratom's proposed monopoly on fissile materials and isotope plants, which yielded limited safeguards for supply security rather than full control due to technical and political hurdles.[25] The United Kingdom, observing via OEEC, disengaged early, rejecting the customs union's supranational features.[25] Bilateral diplomacy and Spaak's mediation during winter 1956–1957 bridged gaps, producing draft treaties by early 1957 for signature on 25 March.[24]Key Compromises on Economic and Institutional Design

The negotiations for the Treaty of Rome, conducted through the Intergovernmental Conference from July 1956 to March 1957 following the Spaak Committee's recommendations, yielded critical economic compromises to reconcile divergent national interests. A core bargain involved integrating agriculture into the common market framework, as France—where farming accounted for about 20% of GDP and employed a quarter of the workforce in 1957—insisted on mechanisms for price stability, market organization, and financial solidarity to protect its producers from competition, in return for dismantling internal tariffs on industrial imports from partners like West Germany.[26][27] West Germany, focused on export-driven manufacturing, agreed to this despite the risk of elevated food costs for its consumers, securing reciprocal access to French markets and gradual elimination of customs duties over a 10- to 12-year transition period for industrial goods.[28] This accord, outlined in Articles 38–55, committed the Community to approximating agricultural policies while prioritizing the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons, though full implementation of the Common Agricultural Policy awaited later regulations.[29] Institutionally, the drafters balanced supranational innovation—building on the European Coal and Steel Community model—with safeguards for state sovereignty, addressing French reservations about ceding control amid its recent decolonization struggles and Gaullist preferences for intergovernmentalism.[30] The Treaty established a Commission as the supranational executive with monopoly on legislative proposals and enforcement powers, alongside a Court of Justice to interpret and apply Community law uniformly across borders.[29] Yet the Council of Ministers, representing national governments, held ultimate decision-making authority, requiring unanimity for core policies such as agriculture, competition rules, and harmonization measures to prevent any single state from being outvoted on vital interests.[30] Qualified majority voting was introduced selectively for implementing customs union and commercial policy after a transitional phase ending around 1970, providing a limited mechanism for efficiency without immediate erosion of veto powers.[29] This hybrid design reflected a pragmatic concession: supranational elements to foster integration and credibility, tempered by intergovernmental checks to secure ratification in skeptical capitals like Paris.[30]Signing Ceremony and Immediate Reactions

The signing ceremony for the Treaties of Rome occurred on 25 March 1957 at the Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy, in the historic Hall of the Horatii and Curiatii within the Palazzo dei Conservatori.[31] Representatives from Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) affixed their signatures to two parallel agreements: the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) and the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom).[32] The signatories included the foreign ministers of each state—Paul-Henri Spaak for Belgium, Christian Pineau for France, Gaetano Martino for Italy, Joseph Bech for Luxembourg, Joseph Luns for the Netherlands, and Heinrich von Brentano for West Germany—along with accompanying prime ministers and dignitaries such as Italian Prime Minister Antonio Segni.[33] The event featured an address by Rome's mayor, Umberto Tupini, underscoring the symbolic importance of the location in the heart of ancient Roman governance.[34] Contemporary press coverage portrayed the signing as a landmark achievement in post-war European reconciliation, with United Press International reporting that the accords pooled atomic energy resources and integrated the economies of 160 million people across the six nations into a common market framework.[35] Leaders emphasized the treaties' role in preventing future conflicts through economic interdependence, echoing the Franco-German reconciliation central to the initiative. French Foreign Minister Christian Pineau described the moment as a "great day for Europe," highlighting commitments to supranational institutions despite lingering national sovereignty concerns.[6] In Italy, the host nation, the ceremony was celebrated as a fulfillment of federalist visions promoted by figures like Alcide De Gasperi, though some domestic critics questioned the pace of integration.[36] Initial reactions varied by country but were predominantly optimistic among proponents of integration. In West Germany, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer viewed the treaties as essential for anchoring the country's economic recovery within a broader European structure, mitigating fears of isolation amid Cold War tensions.[37] Belgian and Dutch officials, represented by Spaak and Luns, welcomed the expansion beyond the European Coal and Steel Community, anticipating trade liberalization benefits. Skepticism emerged in France, where Gaullist factions expressed reservations over the EEC's supranational elements, fearing erosion of agricultural protections and foreign policy autonomy, though the signing proceeded under the Fourth Republic's pro-integration stance.[38] Overall, the event marked a cautious optimism, with ratification debates anticipated to test the accords' viability before their entry into force on 1 January 1958.[6]Core Provisions

Objectives and Foundational Principles

The Treaty of Rome, formally the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), outlined its objectives in the preamble and Article 2, emphasizing economic integration to foster prosperity and stability among the six founding member states: Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. The preamble expressed determination to lay the foundations of an "ever closer union among the peoples of Europe," while resolving to ensure economic and social progress through common action to eliminate barriers dividing the continent, and to promote harmonious development by reducing trade disparities and strengthening international ties.[39][1] These aims were grounded in post-war reconstruction needs, prioritizing practical economic cooperation over immediate political federation, as evidenced by the focus on market mechanisms rather than supranational governance in the initial drafting.[40] Article 2 specified the Community's core aim as promoting harmonious development of economic activities, continuous and balanced expansion, increased stability, accelerated improvement in living standards, and closer relations between member states, to be achieved by establishing a common market and progressively approximating economic policies. This involved creating a customs union to eliminate internal tariffs and adopt a common external tariff, alongside a common market enabling the free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital—principles known as the "four freedoms."[1] Additional objectives included ensuring balanced trade, fair competition, reduction of regional disparities, and approximation of laws to facilitate integration, with activities extending to common policies in agriculture and transport.[7] Foundational principles underpinning these objectives included progressiveness (gradual implementation over transition periods), irreversibility (binding commitments to prevent regression), non-discrimination (prohibiting preferences based on nationality), and openness (allowing future accessions while maintaining core rules).[7] These were designed to create a rule-based system prioritizing economic efficiency and mutual benefit, with the treaty's emphasis on approximation of policies reflecting a causal recognition that divergent national regulations could undermine market unification.[1] The principles avoided ideological overreach, focusing instead on verifiable economic outcomes like tariff reductions (scheduled in stages from 1958 to 1970) to stimulate intra-European trade, which empirical data later showed increased from 30% of members' total trade in 1957 to over 60% by 1972.[40]Establishment of the European Economic Community

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) was signed on 25 March 1957 in Rome by representatives of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany.[6] These six states, building on prior cooperation via the European Coal and Steel Community, sought to foster economic integration through a structured framework that prioritized tariff elimination and policy harmonization.[41] The Treaty entered into force on 1 January 1958 following ratification by all signatories, marking the formal inception of the EEC as a legal entity with defined competencies.[42] The EEC's foundational objective was to establish a customs union and common market, entailing the prohibition of customs duties and quantitative restrictions on trade between members, alongside a unified external tariff against non-members.[4] This mechanism aimed to create an area of undistorted competition by approximating economic policies, including provisions for free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons—the so-called four freedoms—while laying groundwork for common sectoral policies such as agriculture under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).[7] The Treaty's emphasis on gradual implementation, with transitional periods for tariff reductions spanning up to 12 years, reflected pragmatic compromises to accommodate varying national economic structures without immediate disruption.[1] Institutionally, the Treaty vested authority in supranational bodies to ensure enforcement and decision-making beyond pure intergovernmental lines. The High Authority evolved into the Commission, tasked with proposing legislation and safeguarding Treaty implementation; the Council of Ministers, comprising national representatives, held decision-making power often requiring qualified majorities; the Assembly (later Parliament) provided consultative oversight with members appointed by national parliaments; and the Court of Justice upheld legal uniformity through preliminary rulings and enforcement actions.[4] These structures, operational from the EEC's outset, enabled centralized management of competition rules, state aid prohibitions, and anti-dumping measures, embedding causal mechanisms for economic convergence driven by market forces rather than fiscal transfers.[43]Mechanisms for Common Market Creation

The Treaty of Rome established the common market through a phased transition period spanning 12 years from 1 January 1958 to 31 December 1969, during which member states progressively implemented liberalization measures under Council regulations and directives proposed by the Commission.[1][4] Central to this was the creation of a customs union, mandated by Article 9, which prohibited customs duties on imports and exports between members and eliminated quantitative restrictions, while establishing a common external tariff based on the arithmetic average of members' prior duties, convertible at 1957 exchange rates.[4] Internal tariffs were reduced in three equal stages on 1 July of 1960, 1962, and 1964, with full elimination by 1 July 1968 for industrial goods, though agricultural products followed a separate timeline tied to the Common Agricultural Policy.[1][44] Beyond tariff removal, the Treaty addressed non-tariff barriers via harmonization of laws under Article 100, requiring the Council to issue directives for approximating provisions that directly affected the common market, such as health, safety, and fiscal standards, to prevent distortions in competition.[4][40] Free movement of goods was further ensured by Articles 30–34, which banned measures equivalent to quantitative restrictions, including discriminatory internal taxes (Article 95) and state monopolies (Articles 37–38), with exceptions limited to public morality, health, or security under Article 36, subject to Commission oversight.[4] The four freedoms—goods, persons, services, and capital—formed the market's foundational pillars, with Title III (Articles 48–51) mandating progressive abolition of restrictions on worker mobility, including equal treatment in employment and social security portability by the end of the transition period.[40][4] Services and establishment rights (Articles 52–66) required mutual recognition of professional qualifications and elimination of nationality-based discrimination, while capital flows (Articles 67–73) prohibited restrictions on payments linked to current transactions immediately and liberalized others over time.[4] Competition rules in Articles 85–94 prohibited cartels and state aids distorting trade, enforced by the Commission with fines up to 10% of turnover, to maintain a level playing field.[1][4] Sector-specific policies supported integration: the Common Agricultural Policy (Articles 38–47) introduced market organizations with price supports and import levies by 1962, aiming for self-sufficiency without fully eliminating national protections initially; transport policy (Articles 74–84) sought common rules on rates and conditions to prevent cabotage distortions.[1][4] These mechanisms relied on supranational decision-making, with the Commission initiating proposals and the Council deciding by qualified majority after 1966, though early unanimity requirements slowed harmonization in sensitive areas like taxation.[39][4]Institutional Framework and Supranational Elements

The Treaty of Rome established a novel institutional framework for the European Economic Community (EEC), comprising four principal organs: the Commission, the Council, the Assembly, and the Court of Justice.[45] [46] This structure blended supranational authority—where Community institutions could act independently of national governments—with intergovernmental coordination, marking a departure from the more centralized supranationalism of the 1951 European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) High Authority.[29] The design empowered the Commission to drive integration through its exclusive right of initiative, while the Council retained veto powers in sensitive areas, reflecting compromises during negotiations to accommodate French preferences for limited supranationalism.[29] The Commission, as the EEC's executive body under Articles 155–163, consisted of nine members appointed by agreement of the member state governments for renewable six-year terms, required to act independently and in the Community's general interest rather than national ones.[45] It held a monopoly on proposing legislation and policies, ensuring Treaty implementation, and possessed enforcement powers, including the ability to initiate infringement proceedings against non-compliant member states before the Court of Justice.[45] These features underscored its supranational character, positioning it as a guardian of Community law with autonomy to promote uniform economic policies across the six founding states—Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.[45] [29] Complementing the Commission, the Council—composed of one minister-level representative per member state (Article 146)—served as the primary decision-making body, approving Commission proposals through qualified majority voting (QMV) in areas like tariff reductions and competition rules (Article 148), while requiring unanimity for taxation, agriculture, and institutional changes.[45] QMV, weighted by population (e.g., 12 votes for larger states like France and Germany, 4 for smaller ones like Luxembourg), prevented single-state blockages and facilitated supranational progress toward the common market, though it preserved intergovernmental influence by convening at varying ministerial levels depending on the agenda.[45] The Assembly (later evolving into the European Parliament), provided under Articles 137–143, comprised 142 members initially nominated by national parliaments to represent the peoples of the member states, with a consultative role in reviewing legislation and the power to censure and dismiss the entire Commission by a two-thirds majority.[45] Though lacking legislative authority, it introduced a rudimentary supranational democratic element by linking Community decisions to broader public representation, distinct from purely executive or governmental bodies.[46] The Court of Justice (Articles 164–188), with seven judges and two advocates-general appointed for six-year terms by mutual agreement of governments, held supranational jurisdiction to interpret and enforce the Treaty uniformly, including preliminary rulings from national courts and actions against institutions or states for Treaty violations.[45] Its rulings were binding and directly applicable in member states, enabling the direct effect of Community law—a principle later affirmed in case law but rooted in the Treaty's intent for supranational primacy over conflicting national measures in covered fields.[45] This framework, operational from January 1, 1958, laid the groundwork for deeper integration by institutionalizing mechanisms to override national sovereignty in economic matters without full federalism.[29]Ratification and Initial Implementation

Ratification Processes Across Member States

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community was ratified by the parliaments of the six signatory states—Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands—between May and December 1957, following debates that emphasized economic integration and post-war reconciliation without significant opposition or referendums.[47] Unlike the failed European Defence Community treaty, which encountered nationalist resistance, the Rome Treaty's ratification proceeded smoothly, reflecting broad elite consensus on supranational economic cooperation as a bulwark against future conflict.[6]| Member State | Ratification Date | Process Details |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | 23 November 1957 | The Italian Chamber of Deputies approved the treaties on 30 July 1957 by a vote of 311 to 154 with 54 abstentions, followed by Senate ratification with a large majority before formal instrument deposit.[3][48] |

| France | 25 November 1957 | The National Assembly and Senate ratified after debates in the French Union Assembly, with the Senate approving on 28 November by 134 votes to 2 with 2 abstentions, underscoring Gaullist support for economic union amid Fourth Republic instability.[3][49] |

| Belgium | 13 December 1957 | Ratified via parliamentary act on 2 December, aligning with Belgium's federalist traditions and prior ECSC commitments, with minimal domestic contention.[3][50] |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 13 December 1957 | Approved by the Bundestag and Bundesrat, tying into Chancellor Adenauer's strategy for Western integration and sovereignty restoration, ratified without notable delays.[3] |

| Luxembourg | 13 December 1957 | Parliamentary ratification act passed on 30 November, consistent with Luxembourg's advocacy for small-state protections in supranational structures.[3][51] |

| Netherlands | 13 December 1957 | Ratified by the States General after interparliamentary review, reflecting Dutch emphasis on trade liberalization despite initial supranationality concerns.[3] |