Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

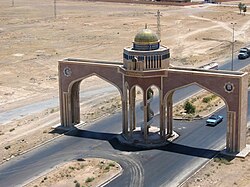

Tikrit

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Tikrit (Arabic: تِكْرِيت, romanized: Tikrīt [ˈtɪkriːt]) is a city in Iraq, located 140 kilometers (87 mi) northwest of Baghdad and 220 kilometers (140 mi) southeast of Mosul on the Tigris River. It is the administrative center of the Saladin Governorate. In 2012, it had a population of approximately 160,000.[2] Tikrit is widely regarded as the cultural capital of Iraqi Sunni Arabs, with control of the city carrying symbolic weight due to its former prestige.

Originally created as a fort during the Assyrian empire, Tikrit became the birthplace of Muslim military leader Saladin. Saddam Hussein's birthplace was in a modest village (13 km) south of Tikrit, which is called "Al-Awja"; for that, Saddam bore the surname al-Tikriti.[3] The inhabitants of this village were farmers. Many individuals from Saladin Governorate, especially from Tikrit, were government officials during the Ba'athist period until the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[4] Following the invasion, the city has been a site of insurgency by Sunni militants, including the Islamic State who captured the city in June 2014. During the Second Battle of Tikrit from March to April 2015, which resulted in the displacement of 28,000 civilians,[5] Iraqi government forces regained control of the city, with the city at peace since then.[6]

History

[edit]Bronze Age to Hellenistic period

[edit]As a fort along the Tigris (Akkadian: Idiqlat), the city is first mentioned in the Fall of Assyria Chronicle as being a refuge for the Babylonian king Nabopolassar after his failed assault on the city of Assur in 615 BC.[7]

Tikrit is usually identified as the Hellenistic settlement Birtha.[8]

Christian presence

[edit]Until the 6th century, Christianity within the Sasanian Empire was predominantly dyophysite under the Church of the East, however, as a result of Miaphysite missionary work, Tikrit became a major Miaphysite (Orthodox Christian) center under its first bishop, Ahudemmeh, in 559.[9] Under Marutha of Tikrit, the bishopric was elevated into a maphrianate and the city's ecclesiastical jurisdiction extended as far as Central Asia.[10]

The city remained predominantly Syriac Orthodox Christian in the early centuries of Islamic rule and gained fame as an important center of Syriac and Christian Arab literature. Some famous Christians from the city include its bishop Quriaqos of Tagrit who ascended to become the patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church, theologians Abu Zakariya Denha and Abu Raita, and translator Yahya ibn Adi.[11]

From the ninth century Christians of Tikrit began to migrate northwards due to restrictive measures taken by some Muslim governors. Many settled in Mosul and villages in the Nineveh Plains, especially Bakhdida, as well as Tur Abdin.[12] The Christian community received a setback when the governor ordered the destruction of the main cathedral known popularly as the "Green Church" in 1089. The maphrian and some of the Christians of Tikrit had to relocate to the Mor Mattai Monastery, where a village named Merki was established in the valley below the monastery. A later governor permitted the reconstruction of the cathedral. However, instability returned and the maphrian moved indefinitely to Mosul in 1156.[12]

Regardless, the city remained an important center of the Syriac Orthodox Church until its destruction by Timur in the late 14th century. A Christian presence has not existed in the city since the 17th century.[11]

Byzantine to Ottoman periods

[edit]The town was also home to the Arab Christian tribe of Iyad. The Arabs of the town secretly assisted the Muslims when they besieged the town. The Muslims entered Tikrit in 640; it was from then considered as part of the Jazira province. It was later regarded as belonging to Iraq by Arab geographers.[11]

Tikrit was briefly controlled by the Nizari Ismailis. After a failed Seljuk campaign against it, the Nizaris handed it over to the local Shia Arabs there.[13]

The Arab Uqaylid dynasty took hold of Tikrit in 1036.

Saladin was born there around 1138.[14] The modern province of which Tikrit is the capital is named after him.

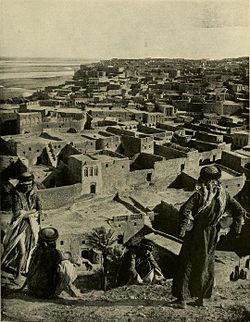

The city was devastated in 1393 by Timur. During the Ottoman period Tikrit existed as a small settlement that belonged to the Rakka Eyalet; its population never exceeded 4,000–5,000.[11]

World War I and after

[edit]

In September 1917, British forces captured the city during a major advance against the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

The Tikriti Jewish community was mostly gone by 1948. By the time Saddam Hussein rose to power there were only two Jewish families in the city.

The city is the birthplace of Saddam Hussein. Many senior members of the Iraqi government during his rule were drawn from Saddam's own Tikriti tribe, the Al-Bu Nasir, as were members of his Iraqi Republican Guard, chiefly because Saddam apparently felt that he was most able to rely on relatives and allies of his family. The Tikriti domination of the Iraqi government became something of an embarrassment to Hussein and, in 1977, he abolished the use of surnames in Iraq to conceal the fact that so many of his key supporters bore the same surname, al-Tikriti (as did Saddam himself).[3] Saddam Hussein was buried near Tikrit in his hometown of Al-Awja following his hanging on December 30, 2006.

Iraq War of 2003 and aftermath

[edit]

In the opening weeks of the 2003 US-led invasion, many observers speculated that Saddam would return to Tikrit as his "last stronghold". The city was subjected to intense aerial bombardment meant to throw Saddam's elite Republican Guard troops out of the city. On April 13, 2003, several thousand U.S. Marines and other coalition members aboard 300 armored vehicles converged on the town, meeting little or no resistance. With the fall of Tikrit, U.S. Army Major General Stanley McChrystal said, "I would anticipate that the major combat operations are over."[15]

However, during the subsequent occupation, Tikrit became the scene of a number of resistance attacks against Coalition forces. It is commonly regarded as being the northern angle of the "Sunni Triangle" within which the resistance was at its most intense. In June 2003, Abid Hamid Mahmud, Saddam Hussein's Presidential Secretary and the Ace of Diamonds on the most wanted 'Deck of Cards,' was captured in a joint raid by U.S. Special Operations Forces and the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment of 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division.

After the fall of Baghdad, Saddam Hussein was in and around Tikrit. He was hidden by relatives and supporters for about six months. During his final period in hiding, he lived in a small hole just outside the town of ad-Dawr, 15 kilometres (9 mi) south of Tikrit on the eastern bank of the Tigris, a few kilometers southeast of his hometown of Al-Awja (although the story of having been found in a hole specifically has come into question as being a piece of war-time propaganda). The missions which resulted in the capture of Saddam Hussein were assigned to the 1st Brigade Combat Teams of the 4th Infantry Division, commanded by Colonel James Hickey of the 4th Infantry Division. The U.S. Army finally captured Saddam Hussein on December 13, 2003 during Operation Red Dawn.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, AFN Iraq ("Freedom Radio") broadcast news and entertainment within Tikrit, among other locations.

On November 22, 2005, HHC 42nd Infantry Division New York Army National Guard, handed over control of Saddam Hussein's primary palace complex in Tikrit to the governor of Saladin Province, who represented the Iraqi government, discontinuing the existence of what once was FOB Danger. The palace complex had served as a headquarter for U.S. 4th Infantry Division, U.S. 1st Infantry Division, and 42nd Infantry Division. The palace complex now serves several purposes for the Iraqi police and army, including headquarters and jails. The U.S. military subsequently moved their operations to al Sahra Airfield, later known as Camp Speicher, northwest of Tikrit.

Saddam Hussein's primary palace complex contained his own palace, one built for his mother and his sons and also included a man-made lake, all enclosed with a wall and towers. Plans for the palace grounds when originally returned to the Iraqi people included turning it into an exclusive and lush resort. However, within weeks of turning over the palace, it was ravaged, and its contents, (furniture, columns, even light switches), were stolen and sold on the streets of Tikrit.

The 402nd Civil Affairs Detachment of the U.S. Army, and the government of Salah ad Din province, began plans to improve local economic conditions. One of the many projects they are working on is building an industrial vocational school in the Tikrit area. The school will teach local people skills in different fields of technology, which will help to build and improve Iraq's economic stability.[16] The curriculum will educate men and women in multiple occupational fields such as the production of high-tech products, plastic production technology, masonry, carpentry, petroleum equipment maintenance and repair, farm machinery and automotive repair. This self-supporting educational institution owns a textile mill where many of the graduates will work producing uniforms. The mill is scheduled to begin producing and selling products within the year, with the profits from the mill going to fund the school. The vocational school's operation, support and funding are modeled after a system South Korea used in another part of Iraq.[16]

On April 18, 2010, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir and Abu Omar al-Baghdadi were killed in a raid 10 km (6 mi) southwest of Tikrit in a safe house.[17]

ISIL insurgence (2011-15)

[edit]

The Islamic State of Iraq launched an attack on March 29, 2011 that killed 65 people and wounded over 100.[19] Reuters news agency included the attack in its list of deadliest attacks in 2011.[20]

On June 11, 2014, during the Northern Iraq offensive, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant took control of the city. Hours later, the Iraqi Army made an attempt to recapture the city, which resulted in heavy fighting.[21] On June 12, ISIL executed at least 1,566[22] Iraqi Air Force cadets from Camp Speicher at Tikrit. At the time of the attack there were between 4,000 and 11,000 unarmed cadets in the camp.[23] The Iraqi government blamed the massacre on both ISIL and members of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Iraq Region.[24] By July 2014, government forces had withdrawn from Tikrit.[25][26]

On September 25, 2014, Islamist militants destroyed the Assyrian Church there that dated back to 700 AD.[27] The historic Al-Arba'een Mosque was detonated as well, damaging the cemetery surrounding it.

In March 2015, the Iraqi Army along with the Hashd Shaabi popular forces launched an operation to retake Tikrit from the Islamic State.[28] On March 31, the Iraqi government claimed the city had been recaptured by the Iraqi Army with the help of Shia militias.[6]

Notable people

[edit]

- Saladin (1137 – 1193), was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty who recaptured Jerusalem

- Saddam Hussein (1937 - 2006), President of Iraq from 1979 until 9 April 2003

- Barzan al-Tikriti (1951 – 2007), one of three half-brothers of Saddam Hussein, and a leader of the Mukhabarat

- Ali Hassan al Majid (1941 – 2010), an Iraqi politician and military commander who was Saddam's defence minister, interior minister and chief of the Iraqi Intelligence Service

- Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr (1914 – 1982), Iraqi politician who served as the president of Iraq, from 17 July 1968 to 16 July 1979

Geography

[edit]Tikrit is about 160 kilometers (99 mi) north of Baghdad on the Tigris River.[29]

The city is located within the semi-undulating area. It penetrates the branch and valleys and ends with very sloping slopes towards the Tigris River, with a height ranging between 45–50 meters.

Climate

[edit]Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as hot desert (BWh).[30]

| Climate data for Tikrit, Iraq | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

40.9 (105.6) |

43.7 (110.7) |

43.7 (110.7) |

39.1 (102.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.1 (98.8) |

32.3 (90.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

17.0 (62.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35 (1.4) |

31 (1.2) |

30 (1.2) |

19 (0.7) |

5 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

11 (0.4) |

25 (1.0) |

33 (1.3) |

189 (7.4) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 57 | 38 | 29 | 20 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 27 | 47 | 63 | 34 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org (altitude: 109m)[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SunMap[31] | |||||||||||||

Culture and community

[edit]The Tikrit Museum was damaged during the 2003 Iraq War.[32][33]

The University of Tikrit was established in 1987 and is one of the largest universities in Iraq.

Tikrit Stadium is a multi-use facility used mostly for football matches and serves as the home stadium of Salah ad Din FC. It holds 10,000 people. There is also a new world-class stadium that meets FIFA standards with a capacity of 30,000 seats being built in Tikrit.[34]

Military facilities

[edit]The Iraqi Air Force has had several air bases at Tikrit: the Tikrit South Air Base, the Tikrit East Air Base and Al Sahra Airfield (Tikrit Air Academy, formerly Camp Speicher).

Transportation

[edit]The city of Tikrit has two small airports; Tikrit East Airport and Tikrit South Airport.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Philip Gladstone (10 February 2014). "METAR Information for ORSH in Tikrit Al Sahra (Tikrit West), SD, Iraq". Gladstonefamily.net. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Iraqis – with American help – topple statue of Saddam in Baghdad". Fox News. 9 April 2003.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Neil (2003-01-05). "THREATS AND RESPONSES: ALLEGIANCES; In Iraq's Tribes, U.S. Faces a Formidable Wild Card (Published 2003)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- ^ Batatu, Hanna. "Class Analysis and Iraqi Society." Arab Studies Quarterly Volume 1, No.3 (1979). 241.

- ^ "Islamic State crisis: Thousands flee Iraqi advance on Tikrit". BBC News. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Iraq hails victory over Islamic State extremists in Tikrit - Times Union". www.timesunion.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- ^ Bradford, Alfred S. & Pamela M. With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. Accessed 18 December 2010.

- ^ Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, s.v. Birtha

- ^ Maas, Michael (18 April 2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–. ISBN 978-1-139-82687-7. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "88- Marutha of Takrit (d. 649)". SyriacStudies.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Gibb, H. A. R. (2000). "Takrīt". In Kramers, J. H. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 10 (Second ed.). BRILL. pp. 140–141. ISBN 9789004112117. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ a b Rassam, Suha (2005). Christianity in Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Gracewing Publishing. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-85244-633-1. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (2011). The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86333-5.

- ^ Malcolm Lyons and D.E.P. Jackson, "Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War", pg. 2.

- ^ "Major combat over". The Age. 15 April 2003. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b "New Vocational School and Textile Mill Boost Economy - DefendAmerica News Article". defendamerica.mil. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Al Qaeda's two top Iraq leaders killed in raid". Reuters. April 19, 2010.

- ^ "Iranian-backed Shiite militias lead Iraq's fight to retake Tikrit - The Long War Journal". 4 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Two journalists among scores killed in insurgent operation in Tikrit". IFEX. 30 March 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Cutler, David (23 February 2012). "Timeline: Deadliest attacks in Iraq in last year". Reuters. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz (13 June 2014). "Iran Deploys Forces to Fight al Qaeda-Inspired Militants in Iraq". Wall Street Journal. Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "ERROR". rudaw.net.

- ^ "Survivors from the Speicher massacre: We were 4000 unarmed soldiers fell into the hands of ISIS". Buratha News Agency (in Arabic). 7 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "ISIS, Saddam's men or a third party who killed 1700 soldiers in camp Speicher in Iraq?". CNN Arabic (in Arabic). 10 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Iraqi forces withdrawn from militant-held Tikrit after new push". Reuters. July 16, 2014.

- ^ "Rebels repel Iraqi attempt to retake Tikrit". Al Jazeera. 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Islamists Destroy 7th Century Church, Mosque in Tikrit, Iraq". 25 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Al-Jawoshy, Omar; Arango, Tim (2 March 2015). Hassan, Falih; Saleh, Ahmed (eds.). "Iraqi Offensive to Retake Tikrit From ISIS Begins". NY Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Shewchuk, Blair. "SADDAM OR MR. HUSSEIN?" (Archive). CBC News. February 2003. Retrieved on June 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Climate: Tikrit - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ^ "Weather in Asia, Iraq, Muḩāfaz̧at Şalāḩ ad Dīn, Tikrit Weather and Climate". Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ^ Iraq - The cradle of civilization at risk ( Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Another war casualty: archeology ( Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ ملعب صلاح الدين الأولمبي سعة 30 ألف متفرج يدخلُ مرحلةً جديدةً من العمل مع الفندق, alnahar.news

External links

[edit]Tikrit

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

Tikrit serves as the capital of Salah ad-Din Governorate in north-central Iraq. The city is situated approximately 100 miles (160 km) northwest of Baghdad.[7] It lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris River, which defines much of the local geography by providing a vital water source amid otherwise arid conditions.[8] The terrain surrounding Tikrit consists primarily of flat alluvial plains typical of the Mesopotamian lowlands, with the city's core elevated on a rocky outcrop overlooking the river. West of the city, the landscape transitions to desert prone to dust storms.[9] Iraq's central region features low elevations and minimal topographic variation, facilitating riverine agriculture but exposing the area to flooding risks.[10]Climate

Tikrit experiences a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), marked by scorching summers, mild winters, and minimal precipitation throughout the year.[11] [12] Annual rainfall averages around 150 mm, primarily occurring between December and February, with summer months receiving negligible amounts, often less than 1 mm.[13] This aridity supports sparse vegetation and contributes to frequent dust storms, especially in transitional seasons. Temperatures exhibit significant diurnal and seasonal variation. Daily highs typically range from 18°C (64°F) in January to over 43°C (109°F) in July, while lows vary from about 3°C (37°F) in winter to 26°C (79°F) in summer; extremes have reached as high as 47°C (117°F) and as low as -3°C (27°F).[11] [14] Relative humidity is low year-round, averaging 30-50%, exacerbating the heat's intensity during summer.[12]| Month | Avg. High (°C) | Avg. Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 18 | 5 | 30 |

| July | 43 | 26 | 0 |

| Annual | 29 | 15 | 150 |