Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wanli Emperor

View on Wikipedia

The Wanli Emperor (4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun,[iv][v] was the 14th emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1572 to 1620. He succeeded his father, the Longqing Emperor. His reign of 48 years was the longest of the Ming dynasty.[3]

Key Information

The Wanli Emperor ascended the throne at the age of nine. During the first ten years of his reign, Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng effectively led the government, while the Emperor's mother, Lady Li, and the eunuch Feng Bao also played significant roles. The country experienced economic and military prosperity, reaching a level of power not seen since the early 15th century. The Emperor held great respect and appreciation for Zhang Juzheng, but as time passed, various factions within the government openly opposed Zhang, and the Emperor started to consider his influential position a burden. In 1582, Zhang died and within months, the Emperor dismissed Feng Bao and made significant changes to Zhang's administrative arrangements.

The Wanli era saw a significant boom in industry, particularly in the production of silk, cotton, and porcelain, and agriculture and trade also experienced growth. Increased trade had the strongest impact in Jiangnan, where cities such as Suzhou, Songjiang, Jiaxing, and Nanjing flourished. Despite the economic growth of the empire, state finances remained in a dire state, and while wealthy merchants and the gentry enjoyed lavish lifestyles, the majority of peasants and day laborers lived in poverty.

Ming China saw three major campaigns in the last decade of the 16th century. A Ming force of 40,000 soldiers had quelled a large rebellion in Ningxia by October 1592, allowing the Ming to shift their focus to Korea. Concurrently, Japan invaded Korea, leading to a joint Korean-Chinese force, including 40,000 Ming soldiers, pushing the Japanese out of most of Korea and forcing them to retreat to the southeast coast by 1593. In 1597, a second Japanese invasion was thwarted, and the suppression of the Yang Yinglong rebellion in southwest China concluded in a few months from 1599 due to Ming forces concentrating there amidst the ongoing war with Japan. In the final years of the Wanli era, the Jurchens grew stronger on the northeastern frontiers and posed a significant threat. In 1619, they defeated the Ming armies in the Battle of Sarhu and captured part of Liaodong.

Over time, the Emperor grew increasingly disillusioned with the constant demoralizing attacks and counterattacks from officials, causing him to become increasingly isolated. In the 1580s and 1590s, he attempted to promote his third son, Zhu Changxun, as crown prince, but faced strong opposition from officials. This led to ongoing conflicts between the Emperor and his ministers for over fifteen years. Eventually, the Emperor gave in and appointed his eldest son, Zhu Changluo, as crown prince in 1601, and Zhu Changluo later succeeded his father as the Taichang Emperor. In 1596, the Wanli Emperor attempted to establish a parallel administration composed of eunuchs, separate from the officials who had traditionally governed the empire, but this effort was abandoned in 1606. As a result, the governance of the country remained in the hands of Confucian intellectuals, who were often embroiled in disputes with each other. The opposition Donglin movement continued to criticize the Emperor and his followers, while pro-government officials were divided based on their regional origins.

Background and accession

[edit]Zhu Yijun, the future Wanli Emperor, was born on 4 September 1563 to Zhu Zaiji,[3] the third son[5] and heir apparent of the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521–1567),[3] and his concubine, Lady Li. He had two older brothers, both of whom died in early childhood before 1563, and a younger brother, Zhu Yiliu (朱翊鏐; 1568–1614), who was created Prince of Lu in 1571.[6] Zhu Zaiji ascended the throne as the Longqing Emperor in 1567.[5] On 5 July 1572, the Longqing Emperor died at the age of 35, and Zhu Yijun succeeded his father two weeks later on 19 July 1572.[1] He adopted the era name Wanli, which means "ten thousand calendars".[7]

The Wanli Emperor was known for his restless and energetic nature during his youth.[8] He was a quick learner,[9][vi] intelligent,[8][9] and perceptive, always staying well-informed about occurrences in the empire.[8] Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng assigned eight teachers to educate the Wanli Emperor in Confucianism, history, and calligraphy. The history lessons focused on teaching him about good and bad examples of governance, and Zhang personally compiled a collection of historical stories for the young emperor to learn from. The Emperor's fascination with calligraphy concerned Zhang, who feared that this "empty pastime" would distract him from his duties as a ruler. As a result, Zhang gradually stopped the Emperor's calligraphy lessons.[11] From 1583 to 1588, the Wanli Emperor visited several mausoleums near Beijing and paid attention to the training of the palace guard. His officials were worried that he would become a ruler similar to the Zhengde Emperor (r. 1505–1521),[12] and discouraged him from traveling outside the Forbidden City and pursuing his interests in the military, horse riding, and archery.[8][12] Under their pressure, the Wanli Emperor stopped leaving Beijing after 1588 and stopped participating in public sacrifices after 1591. He also canceled the morning court audiences (held before dawn) and the evening study of Confucianism with his tutors (after sunset).[12] In his youth, the Emperor was obedient to his mother and showed respect towards eunuchs[vii] and the grand secretaries, but as he aged, he became cynical and skeptical towards rituals and bureaucrats.[14] His opposition to ritualized royal duties linked him to his grandfather the Jiajing Emperor, but he lacked his grandfather's decisiveness and flamboyance. While the Jiajing Emperor was a devoted Taoist, the Wanli Emperor leaned towards Buddhism.[14]

In the first period of his rule, the Wanli Emperor displayed a strong commitment to the well-being of his people, actively combating corruption and striving to improve border defense. His mother, a devout Buddhist, had a significant influence on him, leading him to rarely impose the death penalty, but one punished official claimed that his leniency was sometimes excessive. He was known for being both vulnerable and vengeful, but also generous, and was not afraid to use violence against offending officials, although he did not make it a regular practice.[8] From the mid-1580s, he began to gain weight[12] and his health deteriorated. By 1589, he cited long-term dizziness, accompanied by fevers, heatstroke, eczema, diarrhea, and general weakness as reasons for his absence from audiences. This condition was linked to his regular use of opium.[15][viii]

Zhang Juzheng and Empress Dowager Li raised the Wanli Emperor to be modest in material possessions and exemplary in behavior, which he saw as a humiliation that he never forgot. Upon learning that Zhang himself lived in luxury, the Wanli Emperor was deeply affected. This display of double standards hardened his attitude towards officials and made him cynical about moral challenges. Two years after Zhang's death, his family was accused of illegal land dealings, and the Emperor severely punished them by confiscating their property and sending Zhang's sons to the border troops.[16]

Early reign (1572–1582)

[edit]

At the end of the Longqing Emperor's reign, Senior Grand Secretary Gao Gong headed the government. Shortly after the accession of the Wanli Emperor, however, an alliance between the eunuch Feng Bao (馮保), head of the Directorate of Ceremonial (the most important eunuch office[vii] in the imperial palace), and Zhang Juzheng succeeded in deposing Gao. Zhang took over Gao's place and remained in power for ten years until his death in 1582.[18] Influenced by the Mongol raids of the 1550s, Zhang aimed to "enrich the country and strengthen the army",[ix] using Legalist rather than Confucian methods.[19] He sought to centralize the government and increase the emperor's authority at the expense of local interests by streamlining the administration and strengthening the military.[20] This included closing local academies and placing the investigating censors under the Grand Secretariat's control.[20] Zhang had the support of eunuchs, particularly Feng Bao, and Empress Dowager Li,[21] who acted as regent. He was able to handpick his colleagues in the Grand Secretariat and informally control the Ministry of Rites and the Censorate, appointing his followers to important positions in central offices and regions. This gave him significant influence in the government, although he did not have the authority to issue orders or demands.[21] Zhang also attempted to redirect the censors from seeking revenge against each other and instead focus on collecting taxes and suppressing bandits. As a result, the efficiency of the Ming state administration improved between 1572 and 1582,[22] reaching a level that had only been achieved in the early days of the empire.[23]

Zhang systematically implemented a series of reforms, including the conversion of tax payments from goods to silver (known as the single whip reform), changes to the old military field system,[19] and between 1572 and 1579, revised the accounts of county offices regarding corvée labor and various fees and surcharges.[22] A new cadastre was also created from 1580 to 1582.[24] These reforms were formalized across the empire with the publication of revised lists of taxpayers' duties, now converted to a unified payment in silver.[22] As part of the administrative reforms, unnecessary activities were abolished or limited, the number of Confucian students receiving state support was reduced, and provincial authorities were urged to only require one-third of the previous amount of corvée labor. Additionally, the services provided by post offices were reduced. Despite these changes, taxes remained at their original level and tax arrears were strictly enforced. Zhang was able to accumulate a surplus of income over expenditure.[25] This was a significant achievement, as the Ming state typically operated without reserves in the 16th century. Zhang's administration was able to save money and improve tax collection, resulting in considerable reserves. In 1582, the granaries around the capital held nine years' worth of grain, the Taicang treasury (太倉庫) of the Ministry of Revenue contained 6 million liang (about 223 tons) of silver, the Court of the Imperial Stud (太僕寺) held another 4 million, and an additional 2.5 million was available in Nanjing. Smaller reserves were also available to provincial administrations in Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Guangxi. Despite these achievements, there were no institutional changes during Zhang's time in office. He simply made existing processes more efficient under the slogan of returning to the order from the beginnings of the empire.[26]

As a proponent of peace with the Mongols, Zhang rejected the proposal of Minister of War Tan Lun for a pre-emptive strike against them. Instead, he ordered Qi Jiguang, commander of the northeastern border, to maintain an armed peace.[25] This decision not only allowed for a reduction in the border army, but also resulted in the return of surplus soldiers to their family farms.[22] Zhang not only rejected the notion that military affairs were less important than civilian ones, but also challenged the dominance of civilian dignitaries over military leaders. He appointed capable military leaders such as Qi Jiguang, Wang Chonggu (王崇古), Tan Lun, Liang Menglong (梁夢龍), and Li Chengliang to positions of responsibility. Additionally, he implemented a combination of defensive and offensive measures to strengthen border defenses and fostered peaceful relations with neighboring countries by opening border markets, particularly in the northwest.[27]

Zhang's actions were within the bounds of existing legislation, but critics viewed them as an abuse of power to promote his followers and exert illegitimate pressure on officials. Open criticism was rare until his father's death in 1577. According to the law, Zhang was supposed to leave office due to mourning, but the Emperor chose to keep him in office. This was not unprecedented, but criticism of disrespect for parents was widespread.[23] Despite the fact that the most vocal critics were punished with beatings, Zhang's reputation was damaged. In an attempt to suppress opposition, Zhang then enforced an extraordinary self-evaluation of all high-ranking officials,[28] resulting in the elimination of around fifty opponents.[29]

Zhang died on 9 July 1582. After his death, he was accused of the typical offenses of high officials, including bribery, living in luxury, promoting unqualified supporters, abusing power, and silencing critics.[30] Thereafter, his followers among the officials were dismissed,[31] and in the beginning of 1583, Feng Bao also lost his position.[32][x] The Emperor protected the officers, which boosted their morale to a level not seen since the mid-15th century. The Wanli Emperor's more aggressive military policy was based on Zhang's successes,[20] as he attempted to replace static defense with more offensive tactics and appointed only officials with military experience to lead the Ministry of War.[31] The Emperor also shared Zhang's distrust of local and regional authorities and opposition to factional politics.[20] Like Zhang, the Emperor preferred to solve real problems rather than engage in "empty talk"[xi] and factional conflicts.[34]

Mid-reign (1582–1596)

[edit]

After Zhang's death, a coalition formed between the Emperor's mother,[35] the grand secretaries, the Ministry of Personnel, and the Censorate to ensure efficient administration of the empire. The opposition objected to this alliance and deemed it illegal,[36] but with the absence of a strong statesman in the Grand Secretariat, there was no one to bring the administration under control.[37] Both the Emperor and opposition officials feared the concentration of power in the Grand Secretariat and worked to prevent it.[38] From 1582 to 1591, the Grand Secretariat was led briefly by Zhang Siwei (張四維) and then for eight years by Shen Shixing. Shen Shixing attempted to find compromises between the Emperor and the bureaucracy, while also tolerating criticism and respecting the decisions of ministries and the censors, but his efforts to create a cooperative and cohesive atmosphere were unsuccessful.[36] In 1590, the Grand Secretariat's alliance with the leadership of the Ministry of Personnel and the Censorate fell apart, causing Shen to lose much of his influence.[39] He was eventually forced to resign in 1591 due to his approach to the succession issue, which had lost him the confidence of opposition officials.[37]

After 1582, the Emperor chose the leaders of the Grand Secretariat from among the opponents of Zhang Juzheng (after Shen Shixing, the position was held by Wang Jiaping (王家屏), Wang Xijue, and Zhao Zhigao (趙志皋) until 1601). Except for the short-lived Wang Jiaping, all of Zhang's successors—including Shen Yiguan (沈一貫), Zhu Geng (朱賡), Li Tingji (李廷機), Ye Xianggao, and Fang Congzhe (方從哲)—fell out of favor and were either accused by censors during their lifetime or posthumously.[40][xii]

The opposition to Zhang, led by Gu Xiancheng, was successful in condemning him and purging his followers from the bureaucracy after his death,[41] but this also created an opportunity for the censors to criticize higher-ranking officials, which angered the Emperor and caused dissatisfaction because the critics did not offer any positive solutions.[16] As a result, Zhang's opponents became embroiled in numerous disputes, hindering the restoration of a strong centralized government.[41] From 1585, the censors also began to criticize the Emperor's private life.[16] The Emperor's reluctance to impose harsh punishments emboldened the critics.[42] In response, the Wanli Emperor tried to silence their informers among his servants[16] and gradually stopped responding to comments about himself.[42] In 1588, however, the Emperor's censors accused him of accepting a bribe from one of his eunuchs, which shocked the Emperor and caused him to withdraw from cooperating with officials. He reduced his contact with them to a minimum and canceled the morning audience. He only appeared in public at celebrations of military victories and communication with the bureaucracy was done through written reports, to which he may not have responded. Towards the end of his reign, he also hindered personnel changes in offices, leaving positions vacant and allowing officials to leave without his written consent–which was illegal, but went unpunished.[43] As a result, by 1603, nine of the thirteen regional inspector positions had long remained unfilled, and by 1604, almost half of the prefects and over half of the ministers and vice ministers in both capitals were vacant.[44] The Emperor also deliberately left many positions vacant in the eunuch offices of the palace, particularly the position of head of the Directorate of Ceremonial, in an attempt to weaken communication between eunuchs and officials.[45] This resulted in significant financial savings from unoccupied seats.[44]

The Emperor's lack of involvement in official positions did not affect the administration's responsibility for tax collection.[44] In times of military or other serious issues, he sought advice from responsible officials in ministries and the Censorate, and was not hesitant to appoint capable individuals outside of the traditional hierarchy to handle the situation, but he had a lack of trust in the regular administration and often found ways to bypass it.[46] While he may have left some memoranda unanswered, he actively responded to others. Although the Emperor left some high positions vacant, the authorities were able to function under the guidance of deputies and the country's administration continued to run smoothly. Assistance was provided to those affected by famine, rebellions were suppressed, border conflicts were resolved, and infrastructure was maintained.[47][xiii]

Hundreds of memoranda arrived on the Wanli Emperor's desk daily, but he only read and decided on a handful of them. The rest were handled by commissioned eunuchs, who were equipped with the imperial "red brush".[xiv] These eunuchs mostly confirmed the recommendations and proposals of the grand secretaries, but occasionally made different decisions if they believed the Emperor would not agree with the grand secretaries' proposals.[49]

Despite his desire to reform the civil service, the Emperor was unable to do so, and he also did not want to simply confirm the decisions of the officials. Both sides—the Emperor and the bureaucrats—wanted the other to behave properly, but their efforts were unsuccessful and only served to paralyze each other.[43] As a result of these disputes at the center, the state's control over the countryside weakened.[41]

Succession dispute (1586–1614)

[edit]

In 1586, the issue of succession arose when the Emperor elevated his favorite concubine, Lady Zheng, to the rank of "Imperial Noble Consort" (Huang Guifei),[42][50] placing her only one rank below the Empress and above all other concubines, including Lady Wang, mother of the Emperor's eldest son Zhu Changluo (1582–1620). This made it clear to those around him that he favored Lady Zheng's son, Zhu Changxun (1586–1641)—his third son (the second had died in infancy)—over Zhu Changluo as his successor. This caused a division among the bureaucracy; some officials defended the rights of the first son based on legal primogeniture, while others aligned themselves with Lady Zheng's son.[42] In response to the widespread support for the eldest son's rights among officials, the Emperor postponed his decision.[42] He justified the delay by stating that he was waiting for a son from the Empress.[51] When asked to appoint Zhu Changluo as the crown prince at the age of eight so that his education could officially begin, the Emperor again defended himself by saying that princes were traditionally taught by eunuchs.[10]

In 1589, the Emperor agreed to appoint Zhu Changluo as his successor, but Lady Zheng opposed this decision, causing a wave of controversy and, two years later, even arrests when a pamphlet accusing her of conspiring with high officials against the Emperor's eldest son spread in Beijing. In an attempt to improve her public image, the Emperor made efforts to portray Lady Zheng in a favorable light.[50] This reached its peak in 1594 when he supported her efforts to aid the victims of a famine in Henan. He ordered all Beijing officials of the fifth rank and above to contribute to her cause from their incomes.[52]

The failure to appoint a successor sparked frequent protests from both opposition-minded officials and high dignitaries, such as grand secretaries Shen Shixing (in office 1578–91) and Wang Xijue (in office 1584–91 and 1593–94).[42] Empress Wang[53] and Empress Dowager Li also supported the rights of Zhu Changluo,[51] but the Wanli Emperor did not appoint him as crown prince until 1601, after facing pressure from another round of protests and requests.[51][54] At the same time, the Emperor gave Zhu Changxun the title of Prince of Fu,[43] but kept him in Beijing instead of sending him to the province as originally planned when he turned eighteen in 1604. This fueled rumors that the question of succession was still unresolved.[55] It was not until 1614, after numerous appeals and protests against inaction, that the Emperor finally sent his younger son to his provincial seat.[54][56] This decision was only made after the Emperor's mother firmly advocated for it.[51]

Related to the succession debates was the "case of the attack with the stick" (梃擊案), which greatly damaged the ruler's reputation. In late May 1615, a man with a stick was detained at the crown prince's palace. From the subsequent investigation, it was discovered that the man, Zhang Chai (張差), was mentally unstable[57] and had attempted to use his stick to settle a dispute with two eunuchs. Initially, it was decided that he would be executed to resolve the issue,[45] but Wang Zhicai (王之寀), a prison official, intervened and disputed the claim that Zhang was insane. He pushed for a public investigation involving the Ministry of Justice. This new version of events suggested that Zhang was actually of sound mind and two eunuchs close to Lady Zheng and her brother had invited him to the palace. This raised suspicions that their true intention was to assassinate the crown prince and replace him with Lady Zheng's son.[58] This caused a stir at court. In response, the Emperor took the unprecedented step of summoning all civilian and military officials employed in Beijing and appearing before them[xv] with his family–the crown prince and his children. The Emperor scolded the officials for doubting his relationship with the crown prince, whom he trusted and relied on. The crown prince himself confirmed their close relationship and requested an end to the matter. Ultimately, the Emperor decided to execute Zhang and the two eunuchs involved in the case,[61] but officials from the Ministry of Justice opposed the execution and demanded further investigation. A compromise was reached through the mediation of the grand secretaries—Zhang was executed the following day, while the suspected eunuchs were to be interrogated. The interrogation did take place, but both eunuchs remained under the supervision of the Emperor's eunuchs. On the fifth day after the Emperor's speech, the officials were informed that the two eunuchs had died under palace confinement.[58]

Mine tax crisis (1596–1606)

[edit]

In August 1596, due to poor tax collection and the depletion of the treasury from the costly restoration of the Forbidden City palaces destroyed by fire in April of that year, the Wanli Emperor made the decision to accept proposals for silver mining that had been suggested by lower-level administrators for several years. He dispatched a team consisting of eunuchs, Imperial Guard officers, and representatives from the Ministry of Revenue to the outskirts of Beijing to establish new silver mines. He also sent an Imperial Guard officer to Henan province with the same task, and within a few weeks, other officers and eunuchs were sent to Shandong, Shaanxi, Zhejiang, and Shanxi provinces.[62] There was a long-standing tradition of sending eunuchs to various regions, as the business, trade, and mining industries provided opportunities for them to earn income.[63] However, within a few days, this initiative was met with opposition from local authorities in Beijing, who raised concerns about the potential threat to imperial tombs in the mountains near Beijing and the difficulty of recruiting miners who were still engaged in illegal mining. In response, the Emperor designated a protective zone for the tombs, but did not cancel the mining operation. He also appointed wealthy individuals from the local gentry to manage the mines and oversee necessary investments.[62]

Confucian officials, who were concerned about the erosion of their authority,[63] opposed the Emperor's initiative on ideological grounds, as they believed that the state should not engage in business and compete with the people for profit. They also objected to the Emperor's involvement in the mining industry, as it required the employment of miners who were considered untrustworthy and derogatorily referred to as "mining bandits". Another reason for the gentry and officials' opposition was the fact that eunuchs, a rival power group, were in charge of the mining operations. Furthermore, mining for silver was a complex task that required expertise and skills that the Emperor's eunuchs did not possess. To address this issue, the Emperor appointed wealthy local individuals as mine managers, who were responsible for paying the mining tax and delivering the silver, regardless of the profitability of the mine. As a result, the mining of silver shifted from underground to the coffers of the wealthy, effectively taxing them. American historian Harry Miller bluntly described the Wanli Emperor's actions as an "economic war against the wealthy".[62]

After the war in Korea reignited in 1597, the Emperor made increased efforts to raise additional funds.[64] Due to his lack of trust in the gentry, he began to establish an alternative eunuch regional administration. Gradually, the mining tax commissioners (kuangshi; 礦使; literally 'mining envoy') gained control over the collection of trade and other taxes, in addition to the mining tax (kuangshui; 礦稅) to which the Emperor gave official approval in 1598–1599.[65] The Emperor granted these commissioners the authority to supervise the county and prefectural authorities, and even the grand coordinators. As a result, the imperial commissioners no longer had to consider the opinions of local civil or military authorities. Instead, they could assign tasks to them and even imprison them if they resisted. While the Emperor disregarded the protests of officials against the mining tax and the actions of the eunuchs, he closely monitored the reports and proposals of the eunuchs and responded promptly, often on the same day they arrived in Beijing.[64] In 1599, he dispatched eunuchs to major ports, where they took over the powers of official civil administration.[66] The Emperor finally resolved disputes with officials defending their powers in the spring of 1599 by officially transferring the collection of taxes to mining commissioners.[67] This expansion of eunuch powers and their operations earned the Emperor a reputation among Confucian-oriented intellectuals as one of the most avaricious rulers in Chinese history, constantly seeking ways to fill his personal coffers at the expense of government revenue.[45]

According to American historian Richard von Glahn, tax revenue from silver mines increased significantly from a few hundred kilograms per year before 1597 to an average of 3,650 kg per year in 1597–1606. In the most successful year of 1603, the revenue reached 6,650 kg, accounting for approximately 30% of mining.[68] According to estimates by modern Chinese historians Wang Chunyu and Du Wanyan, the mining tax earned the state an additional 3 million liang (110 tons) of silver, with the eunuch commissioners retaining eight or nine times more. Another estimate suggests that in 1596–1606, the mine commissioners supplied the state with at least 5.96 million liang of silver, but kept 40–50 million for themselves. While officials commonly profited from their positions, eunuchs were known to pocket a significantly larger portion of the collected funds.[69]

At the turn of the years 1605/1606, the Emperor realized that not only gentry officials, but also eunuchs, were corrupt. He also recognized that the mining tax was causing more harm than good. As a result, in January 1606, he made the decision to abandon the attempt at alternative administration and issued an edict to abolish state mining operations. Tax collection was then returned to the traditional authorities.[70] The gentry not only suffered financially from the eunuchs' actions, but also lost control over the financial transactions between the people and the state. This loss of control was a significant blow to their perceived dominance over the people. It was a humiliating experience and disrupted the natural order of things. By 1606, the gentry regained their dominance over both the people and the state as a whole.[71]

Reforms in the selection and evaluation of officials

[edit]In the Ming administrative system, ultimate authority rested with the emperor, but it required an energetic and competent ruler to effectively carry out this power. In cases where the ruler was not capable, the system of checks and balances resulted in collective leadership.[72] This was due to the dispersion of power among various authorities. In the mid-15th century, a system of collective debates (huiguan tuiju; literally 'to rally officials and to recommend collectively') was established to address issues that were beyond the scope of one department.[73] These gatherings involved dozens of officials discussing political and personnel matters. As a result, the importance of public opinion (gonglun; 公論) grew and the autocratic power of the emperor was limited.[74]

During the Wanli Emperor's reign, one of the issues that was resolved collectively was the appointment of high state dignitaries.[74] At the beginning of his reign, Zhang Juzheng successfully abolished collective debates, giving the emperor the power to appoint high officials based on his own suggestions, but after Zhang's death, the debates were reinstated and the emperor's power was once again limited.[73] Despite this, the Wanli Emperor attempted to overcome these restrictions, such as in 1591 when he announced his decision to appoint the Minister of Rites, Zhao Zhigao, as senior grand secretary without consulting with other officials. This decision was met with criticism from Minister of Personnel Lu Guangzu, who argued that it violated proper procedure and undermined the fairness and credibility of the government's decision-making processes. Lu and others believed that collective consideration of candidates in open public debate was a more impartial and fair method, as it eliminated individual bias and ignorance. In response to the criticism, the Emperor partially retreated and promised to follow the proper procedure in the future, but he continued to occasionally appoint high dignitaries without collective debate, which always sparked protests from officials.[73]

In the late Ming period, there was a widespread belief that public opinion held more weight than individual opinions. This was evident in the way political and administrative issues were addressed, with decision-making being based on gathering information and opinions from officials through questionnaires and voting ballots.[75] This also had an impact on the evaluation of officials, as their performance began to be judged not only by their superiors but also by the wider community. In 1595, Minister of Personnel Sun Piyang conducted a questionnaire survey on the conditions of several offices and used the results to persuade the Wanli Emperor to dismiss a certain official from Zhejiang. The survey had received a large number of negative comments, including accusations of corruption and other crimes. This unprecedented event sparked a heated debate, with Zhao Zhigao arguing that anonymous questionnaires should not be the main criteria for evaluation and that no one should be accused of criminal offenses based on unverified information from anonymous sources.[75] Sun defended himself by stating that solid evidence against the individual was not necessary, as they were not being accused or standing trial. He believed that in evaluating officials, it was sufficient for him to impartially discover the widely held opinion of the individual's recklessness through the survey.[76]

The reform of civil servant evaluations resulted in their careers being dependent on their reputation, as determined by the ministry and censors through anonymous surveys filled out by their colleagues.[76] This shift, along with collective debates, elevated the significance of public opinion during the Wanli Emperor's reign, leading to intense public debates and conflicts as groups of officials vied for control of public opinion while the Emperor's authority and the weight of his voice declined.[77]

Donglin movement and factional disputes (1606–1620)

[edit]In 1604,[78][79] Gu Xiancheng, with the suggestion of his friend Gao Panlong (高攀龍), established the Donglin Academy in Wuxi, located in Jiangnan. The academy served as a hub for discussions and meetings.[80] With the support of local authorities and the gentry, the academy quickly gained prominence. As the founders had been out of politics for many years, the government did not view it as a threat.[81] The academy attracted hundreds of intellectuals and soon became a significant intellectual center across China. It also inspired the creation of similar centers in nearby prefectures,[80] forming a network of associations and circles.[79]

The academy described themselves as a group of officials who advocated for strict adherence to Confucian morality.[82] The supporters of the Donglin movement believed that living an exemplary life was essential for cultivating moral character, and they did not differentiate between private and public morality. They believed that one's moral cultivation should begin with the mind/heart, then extend to one's home, surroundings, and public life. This belief was exemplified by Gao Panlong.[83] However, they viewed Zhang Juzheng's decision to not mourn for his father as a sign of being an unprincipled profiteer. They also criticized the Emperor for hesitating to confirm the succession of his eldest son, considering it unethical and unacceptable.[82] The Donglin movement promoted a system of government based on Confucian values, particularly the values of the patriarchal family, which were extended to the entire state. They believed that the local administration should be led by the educated gentry, who would guide the people. In this context, the technical aspects of governance were considered unimportant[84] and any issues with the organization of administration were addressed by promoting Confucian virtues, preaching morality, and emphasizing self-sacrifice for higher goals.[85] Disputes within the movement centered around moral values and qualities, with opponents being accused of immoral behavior rather than professional incompetence.[86][xvi] The emphasis on morality allowed the Donglin movement to claim that they were not pursuing selfish goals, but were united by universal and true moral principles.[80] Although the leaders of the movement did not return to office until the end of the Wanli Emperor's reign, the movement had a significant influence among junior officials in Beijing.[81]

The Donglin movement opposed the concentration of power in the Grand Secretariat and the ministries, advocating for the independence of the censorial-supervising personnel. They also called for limitations on the activities of eunuchs within the imperial palace.[83] Their stance on succession was based on principles, arguing that the ruler does not have the right to unilaterally change fundamental laws of the empire, including succession rules.[86] However, their emphasis on decentralization and prioritizing morality and ideology over pragmatism hindered effective governance of the empire, which was already challenging due to its size and population.[85]

The tendency to equate personal virtue with administrative talent led to morality becoming the main target in factional disputes.[88] The regular evaluation of the capital officials was often used to eliminate opponents. In 1577, Zhang Juzheng used this type of evaluation for the first time, resulting in the removal of 51 of his opponents. Another evaluation in 1581 led to the dismissal of 264 officials in the capital and 67 in Nanjing,[29] which was a significant purge considering that during the late Ming period, there were over a thousand officials serving in the central government in Beijing and almost four hundred in Nanjing.[89] In 1587, Grand Secretary Shen Shixing removed only 31 jinshi, but none from the Ministry of Personnel, the Hanlin Academy, and the Censorate, where factional disputes were common. The censors also demanded the dismissal of the Minister of Works He Qiming (何起鳴), apparently for political reasons (as a supporter of Zhang Juzheng), just a month after his appointment, which angered the Emperor. The Minister was forced to leave, and the Emperor also dismissed the head of the Censorate and transferred the responsible censors to the provinces. This sparked protests against "the Emperor's interference in the independence of the censorial office".[29]

In the 1593 evaluation, the Donglins utilized their positions in the Ministry of Personnel and the Censorate to eliminate the followers of the grand secretaries. The newly appointed Senior Grand Secretary, Wang Xijue, was unable to support his party members. He did, however, request the dismissal of several organizers of the purge during additional evaluations. The head of the Censorate opposed this, but the Emperor ultimately agreed,[90] sparking further protests from junior officials, including future founders of the Donglin Academy.[91][xvii] By the time of the 1599 evaluation, the Donglin opposition had lost its influence, resulting in a more peaceful evaluation.[93] In the 1605 evaluation, the Donglin movement once again attacked their opponents, and through Wen Chun (溫純), the head of the Censorate, and Yang Shiqiao (楊時喬), Vice Minister of Personnel, demanded the dismissal of 207 officials from the capital and 73 from Nanjing. The Emperor did not agree to such a large-scale purge and explicitly stated that several of the accused officials should remain in their positions. This was an unprecedented refusal and sparked sharp criticism, leading to a months-long debate filled with mutual recriminations. Even Heaven seemed to intervene when lightning struck the Temple of Heaven. Eventually, the accused officials were forced to resign, but so were the organizers of the purge, including Grand Secretary Shen Yiguan, the following year. While the Donglins were successful in dismissing their opponents, they did not have suitable candidates for top positions.[94] Even when a candidate like Li Sancai emerged, he was thwarted in the same way—through an attack on his moral integrity—in Li's case, through bribery. This was also the first instance where a connection to the Donglin movement was used as an argument against a candidate.[95]

In the 1611 evaluation, two anti-Donglin factions clashed, resulting in the downfall of their leaders (Tang Binyin (湯賓尹), Chancellor of Nanking University, and Gu Tianjun (顧天俊), teacher of the heir apparent). The career of the highest-ranking Donglin sympathizer, Vice Minister of Personnel and Hanlin Academy scholar Wang Tu (王圖), was also ruined. In the 1617 evaluation, three cliques based on regional origin were in conflict, formed by anti-Donglin censors.[96] In the last decade of the Wanli Emperor's reign, the indecisive bureaucrat Fang Congzhe led the Grand Secretariat, while the Emperor left many high administrative positions vacant for long periods and simply ignored polemical memoranda.[96]

Economy

[edit]Economic developments

[edit]

During the Wanli era, there was a significant boom in industry,[97] particularly in the production of silk, cotton, and porcelain.[98] The textile industry in Shaanxi employed a large number of people, while Guangdong saw the emergence of large ironworks with thousands of workers.[97] This period also saw the development of specialization in agricultural production and a significant increase in interregional trade.[98] The impact of this development was most strongly felt in Jiangnan, where cities such as Suzhou, Songjiang, Jiaxing, and Nanjing flourished. Suzhou, known for its silk and financial industries, saw its population grow to over half a million by the end of the 16th century, while Songjiang became a center for cotton cultivation.[99]

A significant portion of the production was exported in exchange for silver. Between 1560 and 1640, the Spanish colonies in the Americas shipped 1,000 tons of silver across the Pacific, with 900 tons ending up in China. During this same time period, Japan sent 6–7 times more silver to China.[xviii] This influx of foreign silver coincided with the commercialization of the economy, which led to growth in industries such as cotton and silk, as well as the growth of cities and trade, but this commercialization did not result in prosperity for all. Land and rice prices remained stagnant, and even fell in the 1570s and 1580s,[100] before experiencing a sudden increase in 1587–89 due to famines in southern China.[101] Wages and labor productivity in the Jiangnan cotton industry also declined.[100] Contemporary commentators observed that while the market economy was thriving, state finances remained poor. Despite the luxurious lifestyle of urban elites, the majority of peasants and day laborers continued to live in poverty.[102] These economic changes also brought about changes in values, particularly in regards to official Confucian doctrines.[97]

During the 16th century, the Ming state gradually shifted towards the policy of zhaoshang maiban (召商買辦; 'the government purchases from private merchants'). This marked the emergence of a market economy, where traders were no longer mere extensions of the state apparatus and were able to negotiate prices and contract volumes. State contracts also encouraged the growth of private enterprises, while the quality of production in state factories declined. For example, in 1575, the army had to return 5,000 unusable shields. By the late 16th century, army officers were refusing to use goods produced by state workshops and instead demanded silver from the government to purchase equipment on the market. The government obtained the necessary silver by converting compulsory services into payments in the single bar reform.[103] The aim of the reform was to eliminate levies in kind, services, and compulsory work in the lijia system and replace them with a surcharge to the land tax paid in silver.[104] Transfers of various duties to silver payments had been taking place in various counties since the 1520s, with the most intense changes occurring in the 1570s to the 1590s. County authorities throughout the country implemented the reform.[105][xix] The changes proceeded from the more developed south of the country to the north, where the introduction of procedures common in the south caused a wave of resistance. Controversy centered primarily on the repeal of progressive household taxation: advocates of the reform argued that wealthy households usually received tax exemptions, making progressive taxation only fictitious.[106] By the end of the 16th century, land tax surcharges had already replaced almost all benefits and labor performed in the lijia system.[107]

In an effort to streamline the collection of land tax in 1581, Senior Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng advocated for the creation of a new cadastre. Over the course of 1581–1582, fields were measured, boundaries were marked, sizes were calculated, and owners and tenants were recorded. Cadastral maps were also compiled during this time.[108] Due to Zhang's untimely death, there was no final summary of data for the entire country, but at the local level, the work served its purpose.[109] Zhang's cadastre served as the foundation for later Ming and Qing cadastres.[108]

As early as 1581, the Ministry of Revenue had compiled the Wanli kuai ji lu (萬曆會計錄; 'Record of the accounting procedures of the Wanli reign'), which provided an overview of taxes and fees throughout the empire. This document highlighted the complexity, diversity, and dependence on local conditions of these taxes, making unification a challenging task.[84] After incorporating some compulsory works, the land tax amounted to 5–10% of the harvest, but in the four most heavily taxed prefectures of Nanzhili, it reached 14–20%. In the 1570s–1590s, approximately 21 million liang of silver were collected for the land tax, mostly in the form of grain.[110]

Trade

[edit]

Outside of Jiangnan, in most counties of Ming China, few products were traded across borders, with the most important being grain.[111] Grain was primarily imported to Jiangnan from Jiangxi, Huguang, and western Nanzhili, while Beizhili imported rice from Shandong and Beijing imported tax rice. The majority of rice on the market was collected by landlords from their tenants as rent. The grain market also facilitated the production of non-food goods, particularly textiles. In Jiangnan, there were areas that did not grow rice, but instead focused on textile crops such as cotton and mulberry.[112] Mulberries were primarily grown in northern Zhejiang, with Huzhou being a central location.[113] In and around Songjiang, cotton was grown on more than half of the land. The focus was not just on growing and producing goods, but also on selling them. In the late Ming period, the economy in Jiangnan shifted from cultivation to the processing of cotton, which was imported from Shandong, Henan, Fujian, and Guangdong.[114] Suzhou and Hangzhou were known as centers for the production of luxury goods, while ordinary fabrics were produced in the surrounding areas.[115] Within the production process, there was specialization in individual stages, such as spinning and weaving.[116]

Of the various regional merchant groups, those from Shanxi dominated the salt trade in the interior, including Sichuan. Meanwhile, merchants from Huizhou controlled long-distance trade on the Grand Canal and were the most influential wholesalers and retailers in Jiangnan. They were followed by merchants from Suzhou, Fujian, and Guangzhou, in that order. Merchants from Jiangxi operated on a smaller scale, mainly in Henan, Huguang, and Sichuan.[117] Local agents offered boats, crew, and porters for hire on trade routes.[118] Travel guides were published, providing information on routes, distances, inns, famous places, ferries, and safety.[119] Commercial intermediaries allowed for the sending of money through drafts.[120]

Women entrepreneurs emerged, selling various goods, and also acted as intermediaries in legal disputes.[121] Conservatives viewed women's involvement in trade with disdain, as seen in the case of Li Le, who praised a prefect for "banning gambling and women from selling at markets" in the Jiaxing prefecture.[122]

Silver

[edit]The growth of silver imports in the early 16th century led to an increase in its use. By the second half of the 16th century, Ming statesmen were already concerned that silver would completely replace bronze coins. In the late 16th century, the issue of the relationship between silver and coins became a central topic in discussions about monetary policy. Some officials suggested halting the production of coins due to their lack of profitability, while their opponents argued that this was a short-sighted policy that ignored the long-term benefits of increasing circulation. This allowed silver to become the dominant currency.[100] In the 1570s and 1580s, debates about currency were dominated by concerns about silver shortages causing deflation,[123] but these debates died down in the 1590s.[124] The import of silver had a significant impact on the Ming economy. Its price relative to gold and copper fell by half during the Wanli era, but its purchasing power was still greater compared to the rest of the world. The Ministry of Revenue's silver income doubled during the 1570s alone, from about 90 tons to approximately 165 tons per year. The income of local authorities also increased, such as in the Moon Port, the main center of foreign maritime trade, where trade licenses and customs fees grew from 113 kg of silver to over one ton between 1570 and 1594. The influx of silver also led to the export of gold and coins.[98] This influx of silver also had negative effects, as inflation appeared in regions with a surplus of silver in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, such as the southeast coast, Jiangnan, and the Grand Canal.[125]

Coinage

[edit]

Many officials distrusted silver because they feared dependence on its inflow from abroad and did not trust its ability to provide all the functions of money. As a result, they attempted to revive the use of coins.[102] In 1571–1572, the mints were briefly opened, but Zhang Juzheng reopened them in 1576. He restored the mints in Beijing and Nanjing, and later in Yunnan.[126] Additionally, he opened mints in both the northern provinces where coins were commonly used—Shanxi, Shandong, and Henan—as well as in provinces where they were not commonly used—Shaanxi, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Huguang.[127] While the mints in the metropolitan areas were state-owned, licensed entrepreneurs ran those in the provinces.[128] The production of coins faced immediate challenges such as a shortage of copper[xx] and difficulties in hiring qualified personnel.[127] In Jiangxi, for example, the mint was only able to produce 5% of the planned amount of coins. In response, the authorities decreed that at least 70% of tax payments must be made in new coins and encouraged merchants to import coins from surrounding provinces, but merchants often supplied low-quality privately produced coins, which were illegal.[127] Similarly, the introduction of coins failed in Fujian, where silver was already widely used.[127] Zhang's monetary policy was fragmented, with each province's officials making their own decisions on supporting coinage. This led to various issues, such as a revolt in Hangzhou in 1582 when soldiers' salaries were converted into coins in Zhejiang, and the banning of private exchange offices in Jiangxi, which hindered the circulation of new coins. Some provinces also prohibited the export of coins from their territory, while others prohibited coins cast outside their territory.[123][xxi] Attempts to introduce new coins into circulation by selling them at a discount only benefited money changers who bought cheap coins from the authorities and resold them at the normal market price. In some cases, attempts to ban the use of illegal private coins resulted in violent protests and the lifting of the bans.[130] While coins cast in Beijing were accepted by the market,[xxii] low-quality private coins continued to dominate in the south.[128] In 1579, Zhang admitted that the attempt to introduce coins had failed.[128] He closed the Yunnan mint the following year and most of the other provincial mints in 1582, but three mints in Huguang continued to operate, casting different coins and leading to the division of the province into several mint zones.[129] After Zhang's death, his successors and opponents closed most of the mints due to inefficiency.[129] Zhang's opponents argued that the state should not interfere in market and currency affairs and impose a currency that the people did not want. On the other hand, some argued that while silver served as a capital and store of value, coins were essential as a medium of exchange and their production, even if unprofitable, would lead to economic recovery in the long run.[131]

In 1599, the Wanli Emperor returned to an expansive monetary policy. The production of new coins was concentrated in Nanjing,[132] where the capacity of mints increased tenfold, but the circulation of these coins was limited to the immediate vicinity of Nanjing. As a result, there was a surplus of coins in the city, causing their value to decrease from 850 to 1300 per liang of silver. In 1606, floods disrupted the import of metals, causing the price of copper to rise. In response, the state limited coin production[133] and laid off 3,000 workers from the mints. These workers then used their knowledge to produce illegal coins. As a result, private coins began to replace national coins within a few years. The government responded by banning the use of private coins, but this caused money changers to stop accepting any coins as a precaution. Nanjing merchants followed suit, leading to riots among the people. This was especially problematic for day laborers and workers who were paid in coins and relied on merchants accepting them for their daily needs.[134] The use of less valuable private coins became more beneficial for their day-to-day transactions.[135]

Society

[edit]

Only individuals with official status were able to ensure the preservation of a merchant family's wealth. As a result, merchants often encouraged their sons to pursue education and obtain an official rank,[137] but during the first two centuries of the Ming dynasty, only candidates from families of officials, peasants (or landowners), craftsmen, and soldiers were allowed to take the civil service examinations. Merchants were not permitted to participate. In the Wanli era, merchants were finally allowed to participate in the imperial examinations, but only one candidate, Zheng Maohua in 1607, was able to pass the highest level of the examinations, known as the palace examination, and obtain the jinshi rank.[xxiii] Despite this, merchants still managed to pass the examinations by registering under the names of others or posing as peasants or soldiers from a different location.[138] As a result, in the late Ming period, the majority of successful examination candidates came from merchant families.[139]

In the students' environment, the eight-legged essay was an important genre, and mastery of it was crucial for success in examinations. This literary form emerged in the Wanli era and gained popularity over the course of a century. It was not yet rigid and was seen as a challenge for intellectuals to showcase their stylistic dexterity. Esteemed art critics like Li Zhi and Yuan Hongdao valued this genre for its experimental and innovative nature, but mastering the eight-legged essay required more than just individual study. Examiners' favored preferences and stylesbwere constantly changing, giving an advantage to candidates from larger cities who could keep up with these trends. This is why it was beneficial to be part of literary societies. In the 1570s, these societies began publishing successful essays with commentary and criticism.[140][xxiv] Additionally, collections of model essays were published by the authorities starting in 1587.[141]

The study was costly. Even the poorest candidates had to cover at least a third of the cost, often resulting in debt. After being appointed to office, officials had to use their salaries to pay off creditors, who were often wealthy merchants,[142] but official salaries were not high, with county magistrates only earning 87 liang per year in the 16th century.[143]

In 1583, the government tightened control over provincial examinations by selecting chief examiners and their deputies from members of the Hanlin Academy. Previously, these positions were held by teachers in charge of county and prefectural state schools, who typically only passed the provincial examinations.[144][xxv]

Military and foreign policy

[edit]Restoration of Ming military power in the late 16th century

[edit]

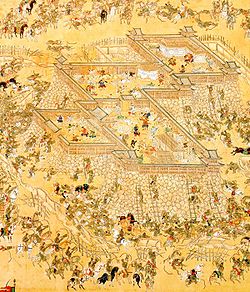

The largest military campaigns of the Wanli era were known as the "Three Great Campaigns". The first of these was the suppression of the rebellion in Ningxia, followed by the Imjin War with Japan in Korea[145] and the suppression of the Yang Yinglong rebellion in Bozhou. These campaigns involved the mobilization of tens and hundreds of thousands of troops, as well as their movement and long-distance supply. The success of the Ming dynasty in these campaigns can be attributed to the overall increase in China's military power during the 1570s to the first decade of the seventeenth century. During this time, the Ming dynasty was aggressively expanding along all frontiers, including launching raids into the Mongolian steppes and supporting the colonization of Han borderlands.[146] In addition to these three major campaigns, the Ming troops also suppressed several rebellions within the empire and successfully expanded and secured the borders in the southwest through battles with the Burmese. This allowed for the colonization of previously indigenous territories in the southwest and northwest. The Ming dynasty also actively interfered in the affairs of the Jurchens in the northeast.[147]

Following the example of his teacher Zhang Juzheng, the Wanli Emperor placed great emphasis on military affairs.[148] This was one of the few areas where most civil officials felt insecure, giving the Emperor the ability to enforce his will.[149] In order to bypass the usual bureaucratic procedures, the Emperor relied on successful generals.[148] In the Emperor's eyes, generals were more dependable and trustworthy than officials, as they spent most of their time in the field and did not have the opportunity to build networks of support in the capital. Additionally, the Emperor saw generals as representatives of a different lifestyle, one that was more free and unartistic.[9] He took great care in selecting capable generals and was not afraid to give them extraordinary powers, allowing them to make quick decisions without waiting for his approval. This contributed greatly to the success of their campaigns. The Wanli Emperor was also willing to allocate significant funds from his reserves to supply and equip the troops,[150] and he entrusted the generals with powers and responsibilities that were typically reserved for civil officials, despite objections from the government.[27]

On the northern border, the Wanli Emperor aimed to replace static defense with more aggressive tactics.[31] In his own words,

The Emperor generally preferred a decisive rather than aggressive approach towards domestic rebels and foreign enemies.[147] Under the leadership of capable generals, the Ming army was the strongest it had been since the reign of the Yongle Emperor (1402–1424).[31] Contemporary estimates put the number of Ming soldiers in the 1570s at 845,000. By the beginning of the 17th century, the Ming dynasty had over 4 million men in arms. Training centers were established near Beijing, where units preparing for Korea also trained.[151] Instead of relying on the inefficient and incompetent hereditary soldiers of the Weisuo system, the Ming government turned to hiring mercenaries who were better trained, more disciplined, and more cost-effective in battle.[152] Troops from militant minority nations were also utilized, particularly "wolf troops" (lang bing) from Guangxi.[153] The development of the military was supported by a number of manuals and handbooks. The most extensive surviving works on military affairs are the Chouhai Tubian (Gazeteer of Coastal Defense) by Zheng Ruozeng in 1562, the Shenqi Pu (Treatise on Firearms) by Zhao Shizhen in 1598, and the Wubei Zhi (Encyclopedia of Military Preparedness) by Mao Yuanyi in 1601.[154] In his manuals Jixiao Xinshu and Lianbing Shiji, General Qi Jiguang provided detailed tactics for using small groups of soldiers, discussed psychological warfare, analyzed the composition, tasks, and training of units, and outlined the use of weapons and procedures based on terrain and soldier experience. He emphasized the importance of morale and training for soldiers.[155]

Rebellion in Ningxia

[edit]In March 1592, a rebellion broke out in Ningxia, an important fortress city on the northwestern frontier. Led by Chinese officer Liu Dongyang, the soldiers of the garrison revolted.[156][157] The rebellion was also joined by Pubei, a Mongol and deputy regional commander who had three thousand horsemen in his personal guard. Due to his origin, the rebellion was attributed to him.[156][157] The rebels successfully took control of Ningxia and nearly fifty nearby fortresses. They demanded recognition from the government, threatening to ally with the Ordos Mongols.[156] At the time, Ningxia had a population of 300,000 and a garrison of 30,000[158] (or 20,000)[159] soldiers. The city walls were six meters thick and nine meters high, making it a formidable stronghold. The rebels were experienced soldiers.[158]

On 19 April, the Emperor was informed of the uprising and immediately summoned Minister of War Shi Xing (石星). Following the minister's proposal, he ordered the mobilization of 7,000 soldiers from Xuanhua and Shanxi.[160][161] Wei Xueceng, an experienced military official and commander-in-chief of the three border regions (Xuanfu, Shanxi, and Datong), was entrusted with the task of suppressing the rebellion. The Emperor provided him with a number of officers and officials, including General Ma Gui.[156][161] Wei successfully secured the southern bank of the Yellow River, captured key forts, and within weeks recaptured nearby frontier forts, leaving only the city of Ningxia under rebel control, but he then declared that he did not have enough men and equipment and took a passive stance. Despite the reinforcements provided, he insisted on negotiating with the insurgents, citing concerns for the lives of civilians in Ningxia.[156] The Emperor discussed the situation with the grand secretaries, the censors and the ministers, and ultimately took a decisive position to suppress the rebellion as quickly as possible.[162] For the next six weeks, Ming troops besieged Ningxia, occasionally facing resistance from the Mongols. In the fourth month of the year, the Ming launched an attack on the city and managed to eliminate about 3,000 defenders, but their attempt to penetrate the city through the northern gate failed and resulted in heavy losses.[156]

In an effort to conduct the siege operations more effectively, the Emperor appointed General Li Rusong as the military superintendent in charge of suppressing the rebellion.[163] The bureaucracy in the capital were shocked at this appointment, as civilian officials, not professional officers, traditionally held the position and overall command.[164] In July, Ming reinforcements arrived at Ningxia and skirmishes between the besiegers and the rebels continued. At the end of July, Li also arrived and began attacking the city day and night in early August. The rebels were only able to repel them with difficulty.[163] Meanwhile, the Japanese were successfully occupying Korea, prompting the Emperor to urge a swift resolution of the situation. In late August, Wei Xueceng was arrested for his reluctance and taken to Beijing. The Emperor then approved Shi Xing's plan to build ramparts around the city and fill the interior, including the city itself, with water.[165]

On 23 August, a 5.3 km long dam surrounded Ningxia. The rebels gained the alliance of Mongol chief Bushugtu, but Li Rusong sent generals Ma Gui and Dong Yiyuan with part of the army to attack them and occupy the passes east of the city. Ma and Dong successfully repulsed the Mongols. By 6 September, the city was already flooded with almost three meters of water, causing the rebels' attacks to fail and the besieged to suffer from a critical shortage of food. The city's inhabitants and Ma Gui pleaded with the insurgents to surrender in order to save human lives, but the rebels continued to launch unsuccessful raids while also facing attacks from Ming troops.[166] By the end of September, the 18,000-strong Mongolian army was blocked north of the city. Li and Ma led a counterattack and drove the Mongols back.[167] As the water breached the walls, the city was eventually taken in mid-October.[159] Pubei committed suicide, while several other rebel leaders were captured and executed.[167][159] The Emperor then sent a large portion of the troops from Ningxia, led by Li Rusong, to Korea.[167][168]

Korea and Japan: Imjin War

[edit]

By the early 1590s, Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi had successfully unified Japan under his rule, but his ambitions extended beyond just ruling over his own country.[169] In challenges sent to the rulers of neighboring countries, he declared his intention to dominate East Asia and establish his rule from the Chinese port of Ningbo.[170] His first target was Korea, with the ultimate goal of conquering Ming China.[169] The Chinese were well aware of the Japanese threat to their hegemony in East Asia and responded with vigor.[171]

In May 1592, Japanese troops landed in Korea. Due to the Korean army's lack of preparation, they were unable to put up much resistance and the Japanese quickly advanced, taking control of Seoul in just twenty days and continuing further north. The Korean king fled north to the Korean-Ming border on the Yalu River.[172] In response, the Koreans sought help from Ming China. The Wanli Emperor decidedly took an anti-Japanese stance and only sent a small scouting force of three thousand soldiers. In August 1592, the Japanese surprised and destroyed this force in Pyongyang.[173] This event shocked the Beijing court and they began to organize coastal defenses. Vice Minister of War Song Yingchang was sent to Liaodong, a Ming region bordering Korea, to take command of the Korean campaign.[174] A large army was also gathered in Liaodong. The Japanese occupation of Korea sparked a wave of popular resistance, which eventually escalated into a guerrilla war. The victories of the Korean navy under Admiral Yi Sun-sin in the summer and autumn of 1592 played a crucial role in organizing the resistance.[169] After the rebellion in Ningxia was defeated, part of the troops and several generals, including Li Rusong, reinforced the troops gathered in Liaodong.[175] The Korean land army also rose up and, in early 1593, the Ming troops, led by Li, went into battle.[169][176] By May 1593, the Sino-Korean forces had pushed the enemy to the vicinity of Busan in southeastern Korea. This led to the Japanese agreeing to negotiate a truce,[169] but the preliminary negotiations dragged on for several years and ultimately failed in October 1596. As a result, Hideyoshi decided to attack Korea again.[177] Despite this, the second invasion in 1597 was not successful. The Japanese did manage to approach Seoul to within 80 km in August 1597, but were eventually pushed back to the southeast after the arrival of Ming troops. Naval operations heavily influenced the outcome of the war. Initially, the Koreans suffered setbacks under an incompetent admiral, but after Yi Sun-sin was released from prison and placed in command of the fleet,[178] they gained superiority at sea. This forced the Japanese onto the defensive between Ulsan and Sunchon. In May 1598, the Ming fleet arrived and reinforced the Korean fleet. Meanwhile, lengthy sieges and bloody battles took place on land. In the spring of 1598, part of the Japanese troops withdrew from Korea, while the rest successfully resisted the Ming-Korean attacks. After Hideyoshi's death in September 1598, the remaining Japanese troops were evacuated from Korea by the end of the year.[178]

The Imjin War was one of the largest military conflicts of the 16th century, with Japan mobilizing over 150,000 soldiers for the first invasion and over 140,000 for the second. The Ming dynasty also sent a significant number of troops, with over 40,000 soldiers in 1592 and more than double that in 1597.[179] According to Chinese historian Li Guangtao, a total of 166,700 Ming soldiers were deployed to Korea and were provided with 17 million liang of silver and supplies, which was roughly equivalent to half a year's income for the Ming state.[180] While the exact number of Korean soldiers is difficult to estimate, it is believed that there were tens of thousands of them.[179] The losses suffered by Korea were devastating, with the Japanese presenting Hideyoshi with the noses of their enemies as proof of their victory instead of the usual heads. Modern historians estimate that the number of noses brought back to Japan ranged from 100,000 to 200,000.[181]

Yang Yinglong rebellion

[edit]

The Yang family, descendants of a 9th-century Tang general, controlled a mountainous region on the border of Huguang, Guizhou, and Sichuan. The area spanned over 300 km in the east-west direction and slightly less in the north-south direction, with its center located in Bozhou.[184] The clan ruled this territory for many centuries and, although originally Chinese, they assimilated and identified with the local Miao tribes over time.[158]

Yang Yinglong inherited his position from his father during the Longqing era. He distinguished himself on the Ming side in battles against other natives and Tibetans, and also received recognition from the Ming court for the quality of the wood he supplied,[185][186] but he was very ambitious and viewed the Ming troops as weak.[185] Problems with Yang Yinglong's actions continued for the local Ming authorities from 1587.[158] He became involved in disputes between the local Miao tribes and Chinese colonists by attacking the former. Initially, the government in Beijing rejected the local authorities' requests for intervention, stating that there were more pressing matters to attend to and that Yang was simply seeking an opportunity to distinguish himself.[185] In 1590, open and protracted fighting broke out between Yang's warriors and Ming forces.[187] Eventually, Yang submitted to the Ming authorities, but was unexpectedly sentenced to execution. In order to secure his release, he offered a large payment and five thousand troops for the war in Korea. After his release, however, he hid in the mountains and plundered a number of prefectures and counties. In 1595, he was caught again and once again escaped punishment by offering a deal. As a result, his son Yang Chaodong was given a hereditary post and another son was sent to Chongqing as a hostage.[188][189] The Emperor considered the matter settled and rewarded the commander, but within a year, Yang Yinglong was once again leading raids on the provinces of Huguang, Sichuan, and Guizhou, and even declared himself emperor. Over the next three years, his hundred thousand Miao soldiers spread fear throughout the area.[188][190]

Focused on the war in Korea, the Wanli Emperor postponed solving the problems in the relatively peripheral southwest of the empire until early 1599, when he appointed the distinguished official Guo Zichang (1543–1618) as pacification commissioner of Sichuan. The former head of the Censorate, Li Hualong, was promoted to vice minister of war and put in charge of the military affairs of Sichuan, Huguang, and Guizhou. Several generals from Korea were sent to Sichuan, including Li Rumei and the well-known and feared Liu Ting (劉綎) in the southwest.[190][191] Fighting with the rebels lasted the rest of the year, while they also attacked the major cities of Chongqing and Chengdu.[188] At the turn of 1599/1600, minor skirmishes took place between the ever-strengthening Ming troops and the rebels. In the end, the Ming army had 240,000 soldiers from all over the empire.[192] Yang Yinglong tried to mobilize indigenous warriors against the superior Ming troops, who were much better armed with cannons and rifles. He gathered perhaps up to 150,000 warriors by the end of 1599.[193][xxvi] but even the Ming armies were largely composed of local natives.[193] After extensive preparations, Li Hualong planned to attack the rebels from eight directions, each with an army of 30,000 men. He launched the attack at the end of March 1600.[193] The Ming troops systematically pushed back the enemy and in early June, surrounded Yang in the mountain fortress of Hailongtun. The fortress fell in a final assault in mid-July,[193] with Yang killed.[192][194] According to Li Hualong's final report, over 22,000 rebels were killed in the fighting.[187]

Yang's chiefdom was then incorporated into the standard Chinese administrative system.[187] In the following decade, Ming military actions continued quite successfully in the southwest, putting down several minor revolts.[192] In an effort to prevent the recurrence of such a large-scale rebellion, the Ming authorities organized a systematic policing of the region.[195]

Đại Việt

[edit]In the 1520s, a civil war broke out in Đại Việt (present-day northern Vietnam) between the Mạc dynasty, which had ruled the northern part of the country since 1527, and the followers of the previous Lê dynasty in the south. In 1592, Lê Thế Tông's army invaded the north and captured Hanoi and most of the country. The followers of the Mạc retreated to Cao Bằng Province and the surrounding area near the Sino-Vietnamese border. The government of Lê Thế Tông, led by Trịnh Tùng, who held more power than the monarch, established connections with the Ming regional authorities in an attempt to gain recognition for the Lê dynasty instead of the Mạc. In 1540, the Jiajing Emperor recognized Mạc Đăng Dung as the ruler of Đại Việt, but the country's status was reduced from a kingdom to a local command (都統使司; dutongshisi), which Đăng Dung administered as a pacification commissioner or commandant (都統使司; dutongshiguan, with the lower second rank). In 1597, after a year of negotiations, Lê Thế Tông arrived at the border with a thousand soldiers and servants to meet with a delegation of Ming regional officials in Ming territory. The meeting was held in a friendly manner, with Thế Tông expressing his desire for Đại Việt to maintain its status as a tributary kingdom, but the Ming representatives did not make any commitments.[196] That same year, Thế Tông sent Vice Minister of Works Phùng Khắc Khoan to Beijing as an envoy.[197] Phùng Khắc Khoan made a good impression in Beijing with his classical education,[198] but he was unable to gain recognition for Lê Thế Tông as the king of Đại Việt. The Wanli Emperor justified this by stating that the civil war was not yet over and it was uncertain if the Lê dynasty had true support. As a result, Thế Tông only received the seal of the pacification commissioner.[199][xxvii]

Spain, Portugal, and Japan

[edit]

In the early 1570s, the Spanish settled in the Philippines, centered in Manila.[202] Trade with the Spanish was highly profitable for the Chinese, as the Spanish bought silk in Manila for double its price in China.[203] The Spanish paid for Chinese goods in American silver, which they imported to China across the Pacific in considerable quantities, estimated to be between 50 and 350 tons per year.[204] This trade between the Spanish Philippines and China flourished,[205] leading to the rapid growth of a Chinatown in Manila.[202] The number of Chinese settlers in Manila increased from forty in the early 1570s to 10,000 in 1588 and 30,000 in 1603.[205] The Spanish authorities viewed the Chinese with suspicion and concern. This mutual distrust often resulted in armed clashes,[202] and in 1603, a pogrom occurred in which 20[203][202] (according to Chinese sources) or 15 (according to Spanish sources) thousand Chinese lost their lives.[202]

During the 1540s, American silver was also introduced to China through the extensive Portuguese trade. Lisbon elites were known to wear Chinese silks, drink Chinese tea, and order porcelain with European motifs from China.[206] The Portuguese had settled in Macau with the consent of local authorities as early as the 1550s. In 1578, they were granted permission to trade in Guangzhou and have continued to do so since then.[207] At the end of the 16th century, between 6 and 30 tons of silver were transported annually from Portugal to Macau.[206] The Dutch also played a significant role in the trade, with the turnover of their trade at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries matching that of the Portuguese. By 1614, Amsterdam burghers were regularly purchasing blue and white Ming porcelain.[208]

In addition to merchants, missionaries also traveled to China from Europe. The Jesuits, in particular, were successful in spreading the Christian faith through their strategic approach of honoring missionaries. Notable figures such as Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci gained the trust of Chinese dignitaries and were able to persuade some to convert to Christianity. The Jesuits were highly esteemed in Beijing's upper circles for their expertise in mathematics and astronomy, and Ricci was even accepted by the Emperor.[209]

In China, silver was a scarce commodity, making it more valuable than in other countries. This was well-known to European traders, who took advantage of the relative cheapness of Chinese goods. As a result, Chinese silk became popular in other parts of the world, such as Latin American countries like Peru and Mexico. This led to a decline in local silk production in Mexico, which had only been introduced by the Spanish a short time before. On the other hand, the textile industry, which utilized Chinese silk, flourished and even exported to European markets. By the 1630s, there was a significant Chinese community in Mexico City, and they also resided in other areas like Acapulco.[210]

After the unification of Japan, the discovery of new silver mines and the improvement of mining techniques, the extraction and export of silver from Japan increased dramatically, particularly to Ming China. Between 1560 and 1600, the annual export of silver ranged from 33 to 49 tons, but due to the Ming ban on trade with Japan, the import of Japanese silver was facilitated by the Portuguese. In the early 17th century, Japanese silver exports continued to rise, with the import of luxury goods such as silk (reaching up to 280 tons per year in the 1630s). Silk was so abundant and inexpensive in Japan that even some peasants were able to afford it, leading to a rise in its popularity among the lower classes.[211]

Russia