Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Women's Protection Units

View on Wikipedia

| Women's Protection Units | |

|---|---|

| Kurdish: Yekîneyên Parastina Jin (YPJ) Arabic: وحدات حماية المرأة | |

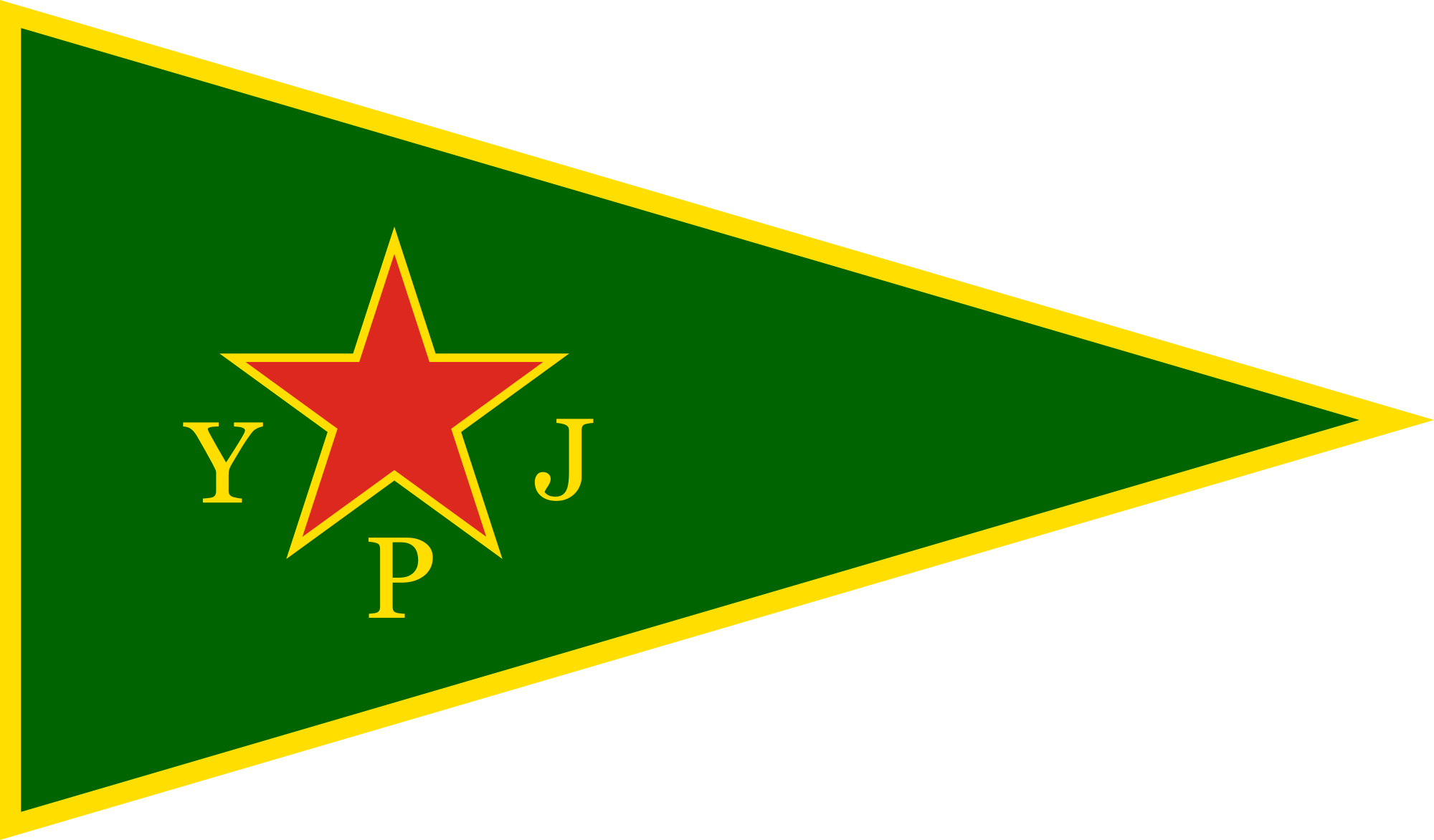

Flag of the YPJ | |

| Active | April 2013–present |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Female service units |

| Type | Light infantry (militia) |

| Size | 24,000 (2017 estimate) |

| Part of | Syrian Democratic Forces (since 2015) |

| Mottos | "Know yourself, protect yourself"[3] |

| Engagements |

|

| Website | https://ypjrojava.net/ |

| Commanders | |

| General Commander[3] | Nesrin Abdullah |

| Kobanî commander[4] | Meryem Kobanî |

| Aleppo commander[5] | Sewsen Bîrhat |

| Leading commander for Raqqa operations[6][7] | Rojda Felat |

The Women's Protection Units[a] (YPJ) or Women's Defense Units is an all-female militia involved in the Syrian civil war.[9] The YPJ is part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, the armed forces of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, and is closely affiliated with the male-led YPG.[10] While the YPJ is mainly made up of Kurds, it also includes women from other ethnic groups in Northern Syria.[11]

History

[edit]Women have been involved in Syrian Kurdish Resistance fighting since as early as 2011, when the mixed-sex YXG was founded, later to be renamed YPG in 2012.[12] The YPJ was founded as a strictly women's organization on 4 April 2013[12] with the first battalion formed in Jindires[13] and later expanded its activities towards the Kobane and Jazira cantons.[14] All female fighters who were previously part of the YPG mixed units automatically became members of the YPJ. Initially, there was just one YPJ battalion in each of the three cantons of Rojava, but battalions were quickly established in every neighborhood, expanding the organization.[12]

Between 2014 and November 2016 the YPJ counted between 7,000 and 20,000 members. As of August 2017, the group was reported to have 24,000 members.[15] After the defeat of ISIL the number has decreased and according to an interview by its General Commander Newroz Ahmed given to The Guardian, is currently at 5,000.[16]

In the Syrian civil war, the YPJ and the YPG have fought against various groups in northern Syria, including the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and were involved in the defense of Kobanî during the Siege of Kobanî[17] beginning in March 2014, with various Kurdish media agencies reporting that "YPJ troops have become vital in the battle".[18] In the Siege of Kobanî, prior to receiving the support of Western powers, the YPJ was forced to hold off ISIL attacks using only "vintage Russian Kalashnikovs bought on the black market, handmade grenades, and tanks they put together out of construction vehicles and pick-up trucks."[11] It was not until October 2014 that the United States began coordinating air strikes with the YPJ-YPG fighters on the ground.[11]

Additionally, the YPG, YPJ and the PKK were involved in an August 2014 military operation at Mount Sinjar, where up to as many as 10,000 Yazidis were rescued from genocide at the hands of ISIL.[19][11][20] ISIL had taken control of most areas around Mount Sinjar after pushing out the Peshmerga.[21] Because ISIL views the Yazidis as "a community of devil worshipers,"[22] those formerly inhabiting the town of Sinjar were forced to flee into the mountains. This left many Yazidis, including children and the elderly, without food, shelter, or resources.[22] Those still in the town were either massacred by ISIL or forced into sexual slavery.[23]

Along with the help of US air strikes, the attacking force was able to create a 30 kilometres (19 mi) safe zone for the Yazidi refugees to escape ISIL capture. The refugees were then moved into Northern Syria, with most later departing for safer areas of Iraqi Kurdistan.[24]

YPJ continues to fight alongside YPG as part of the multi-ethnic Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).[11] The YPJ was involved in battles such as the SDF offensive against the major IS strongholds in Tabqa and Raqqa, serving as the main proxy[25] force (along with the YPG) for the United States.[26] During Operation Olive Branch, the Turkish offensive against Afrin Canton, YPJ units were again heavily involved in the fighting.[27] Guerrilla warfare tactics were among the tactics used against Turkey and their Syrian rebel allies.

During the 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria, Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army fighters trampled and mutilated the body of what appeared to be a YPJ fighter they killed in the countryside near Kobanî.[28]

Ideology

[edit]The YPJ is politically aligned to the PYD, which bases its philosophy on the writings of Abdullah Öcalan,[29] the leading ideologue in the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), who is imprisoned by Turkey. Central to YPJ ideology is the PYD's ideological concept of "Jineology".[30]

Dating back to the early 1990s, Öcalan had been advocating that a ‘basic responsibility’ of the Kurdish movement was to liberate women. He stated that gender equality and women's liberation is necessary for Kurdish liberation. The PKK established its first all-female units of guerrillas in 1995, stating that in order to "break down gender roles solidified by centuries, women had to be on their own."[30] The YPJ adheres to the same strand of feminist ideology. Having joined the YPJ, women must spend at least a month practicing military tactics and studying the political theories of Öcalan, including Jineology. In any communal decision, regarding the YPJ/YPG or otherwise, it is required that no less than 40% of women participate.[31]

The group has been praised by feminists for confronting traditional gender expectations and redefining the role of women in conflict in the region.[32][33] YPJ militants often enter the militia over hardships endured in the family, like lost relatives caused by attacks or fighting.[33] They play a role in changing the societal traditions by taking arms. These women say they are changing their community and society by doing so.[34] The YPJ has attracted international attention as an example of significant achievement for women in a region in which women are systematically disadvantaged.[35][36][37][38]

Another all-female force in northern Syria is the Bethnahrain Women's Protection Forces, which was formed as an Assyrian all-female brigade of the Syriac Military Council, seemingly inspired by the example of the YPJ. The Al-Bab Military Council, Kurdish Front and Liwa Thuwar al-Raqqa have also established their own female units.[39][40]

Abdullah Öcalan's ideas surrounding women's rights have been integral to the founding of the YPJ. Öcalan argued that "the struggle for women's freedom must be waged through the establishment of their own political parties, attaining a popular women's movement, building their own nongovernmental organizations and structures of democratic politics."[41] Öcalan developed this idea in 1996 when he published his theory of separation, which asserts that "if it is held that revolution cannot be made for the people, but rather by the people, then it must be held that revolution cannot merely be made for women but by women.”[42] The YPJ makes women an integral part of the governmental structure of Rojava as well as giving women an independent military unit which aligns with the theory of separation. As such the YPJ is an example of the manifestation of Kurdish political ideology particularly regarding women's role in nation building.

Recruitment

[edit]The YPJ (Women's Defense Units) recruits primarily single women for active combat roles. Married women with children are often assigned to non-combat roles in public relations, administration, and recruitment.[43] Although the bulk of YPJ fighters are Kurdish women, Kurdish forces in Syria declared in 2017 that they will establish a battalion and training facility for Arab women to join the battle against the Islamic State group [IS].[44] YPJ is a volunteer army, and there is no compulsory recruitment. Some impoverished families receive financial compensation for their daughters' service. Women are allowed five days off per month to visit their families, but not all choose to do so, especially if their families discourage their return to the front lines. In contrast to men, who can go home every ten days, the rules for women's visits are more flexible, as YPJ makes its own decisions based on their unique perspectives and priorities.[45] This reflects a distinct approach from Western feminism, as the women in YPJ have experienced a more direct and tangible form of oppression compared to many in the West, where oppression can be subtler, leading some to deny its existence.[43]

Foreign volunteers

[edit]Through the Syrian civil war hundreds traveled from Europe, Turkey and others to join the YPJ/YPG,[46] some out of political affinity and others out of a desire to fight ISIS.[47] On March 16, 2018, Anna Campbell became the first British woman to die while fighting as a part of the YPJ. Campbell had left her home in Lewes, East Sussex to go to Rojava and join the YPJ out of a desire to defend the revolution. She was killed by Turkish missile in the city of Afrin during Operation Olive Branch.[48] Since her enlistment, a number of other British women, such as Rûken Renas, have also signed up to fight with the YPJ.[49]

Hanna Bohman is another YPJ fighter hailing from the western hemisphere, in her case Canada. After nearly dying in a motorcycle incident, Bohman decided to leave her home in Vancouver, Canada to join the YPJ in February 2014.[50]

Additionally, Arab and Yazidi women that the YPJ liberated from ISIS have also begun fighting against their former oppressors.[51] The YPJ has set up institutions where these women are trained both militarily, as well as in fields such as feminist history and philosophy.[52] The Yazidi population has since created its own self defense force, the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBŞ).[53]

Supply

[edit]The YPJ relies on local communities for supplies and food.[32] The YPJ (along with the YPG) received 27 bundles totaling 24 tons of small arms and ammunition as well as 10 tons of medical supplies from the United States and the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraqi Kurdistan during the Siege of Kobanî.[54]

Child soldiers

[edit]In 2020, the United Nations reported that the YPG/YPJ had the most child soldier recruits of any faction in the Syrian civil war, with 283 child soldiers followed by Tahrir al-Sham with 245 child soldiers.[55] This comes despite a 2014 agreement made with the human rights group Geneva Call promising an end to recruitment of soldiers under the age of 18.[56][57][58] Since the agreement, the YPJ has actually recruited more children into their ranks.[59]

Recognition

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]- The 2018 French war drama Girls of the Sun, directed by Eva Husson, is a fictional depiction of the YPJ and their exploits during the Syrian Civil War inspired on true events.[61]

- The 2022 Kurdish film Kobanê depicts the role of women fighters of the YPJ in the Siege of Kobanî.

- The women fighters of the YPJ are depicted in season six of SEAL Team.

- The 2023 Documentary Dream's Gate, directed by Negin Ahmadi depicts the role of women fighters of the YPJ during Civil war,she ventured into the war-torn region with her video camera in 2016.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ (Kurdish: Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, YPJ, pronounced [jɛkiːnɛjeːn pɑːɾɑːstɯnɑː ʒɪn] ⓘ;[8] Arabic: وحدات حماية المرأة, romanized: Waḥdāt Ḥimāyat al-Marʼa; Classical Syriac: ܚܕܝ̈ܘܬܐ ܕܣܘܬܪܐ ܕܢܫ̈ܐ, romanized: Ḥḏāywāṯā ḏa-Suṯārā ḏa-Nešē)

- ^ "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "PYD announces surprise interim government in Syria's Kurdish regions". Rudaw. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Syrian Kurds' morale high but arms needed, YPJ commander". ANSAMed. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Interview with YPJ Commander in Kobane and Mishtenur Hill". 17 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Aleppo: New Group of YPG/YPJ Fighters Graduated from Training Course". YPG Rojava. 23 April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Moritz Baumstieger (9 November 2016). "Profil – Rojda Felat. Kommandeurin der Offensive gegen den IS in Raqqa und Bismarck-Fan. [Profile – Rojda Felat. Commander of the offensive against the IS in Raqqa and Bismarck-Fan]". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Wrath of Euphrates Operations Room, commandant Rojda Felat, Northern Raqqa". YPG. 10 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "#YPJ Female Fighters Shaking #ISIL... – The Lions Of Rojava". facebook.com. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Başer, Çağlayan (2022). "Women Insurgents, Rebel Organization Structure, and Sustaining the Rebellion: The Case of the Kurdistan Workers' Party". Security Studies. 31 (3): 381–416. doi:10.1080/09636412.2022.2097889. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 250577246. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Alt URL

- ^ de Jong, Alex (2016). "A Commune in Rojava?". New Politics. 15 (4).

- ^ a b c d e Tax, Meredith (2016). A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State. Bellevue Literary Press. ISBN 978-1-942658-10-8.

- ^ a b c Knapp, Michael; Flach, Anja; Ayboga, Ercan (2016). Revolution in Rojava : democratic autonomy and women's liberation in Syrian Kurdistan. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745336596.

- ^ Jan Kalan (3 March 2013). "Formation the first battalion of women's protection units in western Kurdistan".

- ^ "Explainer: Military and self defense forces in North and East Syria". Rojava Information Center. 27 May 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Argentieri, Benedetta (18 August 2017). "Meet the female soldiers in Syria and Iraq fighting for gender equality as much as freedom". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Flock, Elizabeth (19 July 2021). "'Now I've a purpose': why more Kurdish women are choosing to fight". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b Tank, Pinar (2017). "Kurdish Women in Rojava: From Resistance to Reconstruction". Die Welt des Islams. 57 (3–4): 406. doi:10.1163/15700607-05734p07. ISSN 0043-2539. JSTOR 26568532.

- ^ "YPJ: The Kurdish feminists fighting Islamic State". The Week UK. 7 October 2014. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014. [verification needed]

- ^ "Kurds press Sinjar operation in north Iraq". gulfnews.com. 20 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "These Remarkable Women Are Fighting ISIS. It's Time You Know Who They Are". Marie Claire. October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Varghese, Johnlee (10 August 2014). "ISIS Threat: Kurdish Forces Rescue 10,000 Yazidis from Sinjar Mountains". International Business Times: Indian Edition.

- ^ a b Varghese, Johnlee (6 August 2014). "ISIS Threat: 25,000 Children Starving in Sinjar Mountains [Photos]". International Business Times: Indian Edition.

- ^ Report on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict in Iraq: 6 July – 10 September 2014. UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ Shelton, Tracey (29 August 2014). "'If it wasn't for the Kurdish fighters, we would have died up there'". Global Post. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Gardner, David (4 April 2017). "Chaos will reign when Isis loses Raqqa". Financial Times.

- ^ "The commander Clara: 4 stages achieved their aims". Hawar News Agency. 7 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018. [verification needed]

- ^ Nordland, Rod (30 January 2018). "Female Kurdish Fighter Kills Turkish Troops in Likely Suicide Bombing in Syria". The New York Times. [verification needed]

- ^ "Syria conflict: The 'war crimes' caught in brutal phone footage". BBC News. 3 November 2019.

- ^ Argentieri, Benedetta (3 February 2015). "One group battling Islamic State has a secret weapon – female fighters". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ a b Paul White, "Democratic Confederalism and the PKK’s Feminist Transformation," in The PKK: Coming Down from the Mountains (London: Zed Books, 2015), pp. 126–149.

- ^ Knapp, Michael. 2016. Revolution in Rojava : Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation in Syrian Kurdistan. [Place of publication not identified]: Pluto Press.

- ^ a b "YPJ: The Kurdish feminists fighting Islamic State". The Week UK. 7 October 2014. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ a b Tank, Pinar (2017), p.410

- ^ (in Dutch) How the fight against ISIS empowered Kurdish women The Correspondent, 17 December 2014

- ^ "The Fight Against ISIS in Syria And Iraq December 2014 by Itai Anghel". The Israeli Network via YouTube. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Fact 2015 (Uvda) – Israel's leading investigative show". The Israeli Network. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Kurdish female fighters named 'most inspiring women' of 2014". Rudaw. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Meet The Kurdish Women Fighting ISIS". All That Is Interesting. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Inspired by Kurdish units, al-Bab Military Council creates all-female battalion – ARA News". 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "بيان إلى الرأي العام". Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Tzemach Lemmon, Gayle (2021). The Daughters of Kobani (1st ed.). United States of America: Penguin Random House. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780525560708.

- ^ Cartier, Marcel (2019). Serkeftin, A narrative of the Rojava revolution. Zero Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9781789040128.

- ^ a b "Women on the front at Raqqa: an interview with Kimmie Taylor". openDemocracy. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "Kurds recruiting Arab women to fight IS in Syria". New Arab. 5 January 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ Mellows, Lauren (7 May 2015). "Case Study: Recruitment of Girls into Militant Groups". ICAN. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ Fox, Kara; CNN. "America's other fighters". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ "International volunteers: ideal and reality | libcom.org". libcom.org. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ Blake, Matt (19 March 2018). "British woman killed fighting Turkish forces in Afrin". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Blake, Matt (23 March 2018). "'Thousands could die': female British fighter urges support for Syria's Kurds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ O'Malley, Katie (20 December 2017). "Meet The Canadian Who Fights ISIS Alongside 10,000 Women". ELLE. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "'We want revenge': Meet the Yazidi women freeing their sisters from Isis in Raqqa". The Independent. 8 October 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "So many women have volunteered to fight Isis they need to build new academies for female fighters". The Independent. 4 January 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Yazidis battle ISIL: Disaster 'made us stronger'". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Istanbul, Constanze Letsch in. "US drops weapons and ammunition to help Kurdish fighters in Kobani". the Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "General Assembly Security Council Seventy-fourth session Seventy-fifth year Agenda item 66 (a) Promotion and protection of the rights of children" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Syria: new measures taken by the Kurdish People's Protection Units to stop recruiting children under 18". Geneva Call. 22 June 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Child soldiers and the YPG". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "U.S.-backed Kurds to Halt Child Soldier use in Syria". Inter Press Service. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "SDF continues to recruit child soldiers, despite pledges to stop the practice". Syria Direct. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "The women of the year". CNN. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "'Girls of the Sun' Is an Homage to Kurdish Women Fighters". Vice. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ 'Is This Really Me?': On The Front Line In Syria With Female Kurdish Fighters, 28 July 2023, retrieved 27 October 2023

Bibliography

[edit]- Rashid, Bedir Mulla (2018) [1st pub. 2017]. Military and Security Structures of the Autonomous Administration in Syria. Translated by Obaida Hitto. Istanbul: Omran for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018.