Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hyphen

View on Wikipedia

| ‐ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hyphen | |||||

| |||||

The hyphen ‐ is a punctuation mark used to join words and to separate syllables of a single word. The use of hyphens is called hyphenation.[1]

The hyphen is sometimes confused with dashes (en dash –, em dash — and others), which are wider, or with the minus sign −, which is also wider and usually drawn a little higher to match the crossbar in the plus sign +.

As an orthographic concept, the hyphen is a single entity. In character encoding for use with computers, it is represented in Unicode by any of several characters. These include the dual-use hyphen-minus, the soft hyphen, the nonbreaking hyphen, and an unambiguous form known familiarly as the "Unicode hyphen", shown at the top of the infobox on this page. The character most often used to represent a hyphen (and the one produced by the key on a keyboard) is called the "hyphen-minus" in the Unicode specification because it is also used as a minus sign. The name derives from its name in the original ASCII standard, where it was called "hyphen (minus)".[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word is derived from Ancient Greek ὑφ' ἕν (huph' hén), contracted from ὑπό ἕν (hypó hén), "in one" (literally "under one").[3][4] An (ἡ) ὑφέν ((he) hyphén) was an undertie-like ‿ sign written below two adjacent letters to indicate that they belong to the same word when it was necessary to avoid ambiguity, before word spacing was practiced.

History

[edit]

The first known documentation of the hyphen is in the grammatical works of Dionysius Thrax. At the time hyphenation was joining two words that would otherwise be read separately by a low tie mark between the two words.[5] In Greek these marks were known as enotikon, officially romanized as a hyphen.[6]

With the introduction of letter spacing in the Middle Ages, the hyphen, still written beneath the text, reversed its meaning. Scribes used the mark to connect two words that had been incorrectly separated by a space. This era also saw the introduction of the marginal hyphen, for words broken across lines.[7]

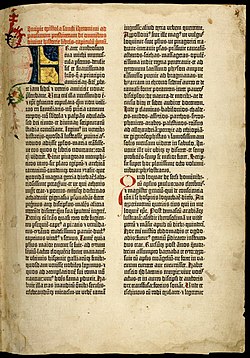

The modern format of the hyphen originated with Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, c. 1455 with the publication of his 42-line Bible. His tools did not allow for a sublinear hyphen, and he thus moved it to the middle of the line.[8] Examination of an original copy on vellum (Hubay index #35) in the U. S. Library of Congress shows that Gutenberg's movable type was set justified in a uniform style, 42 equal lines per page. The Gutenberg printing press required words composed of individual movable type to be secured within a rigid, nonprinting frame. To ensure each line fit the frame uniformly, Gutenberg addressed differences in line length by inserting a hyphen at the end of a line at the right-hand margin. This interrupted the letters in the last word, requiring the remaining letters be carried over to the start of the line below. His double hyphen, ⸗, appears throughout the Bible as a short, double line inclined to the right at a 60-degree angle.[citation needed]

Use in English

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. Almost nothing in this section is tied to reliable sources, and there's a great deal of prescriptivist punditry about "codification" of various "rules". (January 2016) |

The English language does not have definitive hyphenation rules,[9] though various style guides provide detailed usage recommendations and have a significant amount of overlap in what they advise. Hyphens are mostly used to break single words into parts or to join ordinarily separate words into single words. Spaces are not placed between a hyphen and either of the elements it connects except when using a suspended or "hanging" hyphen that stands in for a repeated word (e.g., nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers). Style conventions that apply to hyphens (and dashes) have evolved to support ease of reading in complex constructions; editors often accept deviations if they aid rather than hinder easy comprehension.

The use of the hyphen in English compound nouns and verbs has, in general, been steadily declining. Compounds that might once have been hyphenated are increasingly left with spaces or are combined into one word. Reflecting this changing usage, in 2007, the sixth edition of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary removed the hyphens from 16,000 entries, such as fig-leaf (now fig leaf), pot-belly (now pot belly), and pigeon-hole (now pigeonhole).[10] The increasing prevalence of computer technology and the advent of the Internet have given rise to a subset of common nouns that might have been hyphenated in the past (e.g., toolbar, hyperlink, and pastebin).

Despite decreased use, hyphenation remains the norm in certain compound-modifier constructions and, among some authors, with certain prefixes (see below). Hyphenation is also routinely used as part of syllabification in justified texts to avoid unsightly spacing (especially in columns with narrow line lengths, as when used with newspapers).

Separating

[edit]Justification and line-wrapping

[edit]When flowing text, it is sometimes preferable to break a word into two so that it continues on another line rather than moving the entire word to the next line. The word may be divided at the nearest break point between syllables (syllabification) and a hyphen inserted to indicate that the letters form a word fragment, rather than a full word. This allows more efficient use of paper, allows flush appearance of right-side margins (justification) without oddly large word spaces, and decreases the problem of rivers. This kind of hyphenation is most useful when the width of the column (called the "line length" in typography) is very narrow. For example:

| Justified text without hyphenation |

Justified text with hyphenation | |

|

We, therefore, the |

We, therefore, the represen- |

Rules (or guidelines) for correct hyphenation vary between languages, and may be complex, and they can interact with other orthographic and typesetting practices. Hyphenation algorithms, when employed in concert with dictionaries, are sufficient for all but the most formal texts.

It may be necessary to distinguish an incidental line-break hyphen from one integral to a word being mentioned (as when used in a dictionary) or present in an original text being quoted (when in a critical edition), not only to control its word wrap behavior (which encoding handles with hard and soft hyphens having the same glyph) but also to differentiate appearance (with a different glyph). Webster's Third New International Dictionary[11] and the Chambers Dictionary[12] use a double hyphen for integral hyphens and a single hyphen for line-breaks, whereas Kromhout's Afrikaans–English dictionary uses the opposite convention.[13] The Concise Oxford Dictionary (fifth edition) suggested repeating an integral hyphen at the start of the following line.[14]

Prefixes and suffixes

[edit]Prefixes (such as de-, pre-, re-, and non-[15]) and suffixes (such as -less, -like, -ness, and -hood) are sometimes hyphenated, especially when the unhyphenated spelling resembles another word or when the affixation is deemed misinterpretable, ambiguous, or somehow "odd-looking" (for example, having two consecutive monographs that look like the digraphs of English, like e+a, e+e, or e+i). However, the unhyphenated style, which is also called closed up or solid, is usually preferred, particularly when the derivative has been relatively familiarized or popularized through extensive use in various contexts. As a rule of thumb, affixes are not hyphenated unless the lack of a hyphen would hurt clarity.

The hyphen may be used between vowel letters (e.g., ee, ea, ei) to indicate that they do not form a digraph. Some words have both hyphenated and unhyphenated variants: de-escalate/deescalate, co-operation/cooperation, re-examine/reexamine, de-emphasize/deemphasize, and so on. Words often lose their hyphen as they become more common, such as email instead of e-mail. When there are tripled letters, the hyphenated variant of these words is often more common (as in shell-like instead of shelllike).

Closed-up style is avoided in some cases: possible homographs, such as recreation (fun or sport) versus re-creation (the act of creating again), retreat (turn back) versus re-treat (give therapy again), and un-ionized (not in ion form) versus unionized (organized into trade unions); combinations with proper nouns or adjectives (un-American, de-Stalinisation);[16][17] acronyms (anti-TNF antibody, non-SI units); or numbers (pre-1949 diplomacy, pre-1492 cartography). Although proto-oncogene is still hyphenated by both Dorland's and Merriam-Webster's Medical, the solid (that is, unhyphenated) styling (protooncogene) is a common variant, particularly among oncologists and geneticists.[citation needed]

A diaeresis may also be used in a like fashion, either to separate and mark off monographs (as in coöperation) or to signalize a vocalic terminal e (for example, Brontë). This use of the diaeresis peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but it was never applied extensively across the language: only a handful of diaereses, including coöperation and Brontë, are encountered with any appreciable frequency in English; thus reëxamine, reïterate, deëmphasize, etc. are seldom encountered. In borrowings from Modern French, whose orthography utilizes the diaeresis as a means to differentiate graphemes, various English dictionaries list the dieresis as optional (as in naive and naïve) despite the juxtaposition of a and i.[citation needed]

Syllabification and spelling

[edit]Hyphens are occasionally used to denote syllabification, as in syl-la-bi-fi-ca-tion. Various British and North American dictionaries use an interpunct (sometimes called a "middle dot" or "hyphenation point"), for this purpose, as in syl·la·bi·fi·ca·tion. This practice allows the hyphen to be reserved exclusively for instances where a true hyphen is intended – for example, self-con·scious, un·self-con·scious, and long-stand·ing. Similarly, hyphens may be used to indicate the spelling of a word, as in W-O-R-D to represent word.

In nineteenth-century American literature, hyphens were also used irregularly to divide syllables in words from indigenous North American languages, without regard for etymology or pronunciation,[18] such as "Shuh-shuh-gah" (from Ojibwe zhashagi, "blue heron") in The Song of Hiawatha.[19] This usage is now rare and deprecated,[citation needed] except in some place names such as Ah-gwah-ching.

Joining

[edit]Compound modifiers

[edit]Compound modifiers are groups of two or more words that jointly modify the meaning of another word. When a compound modifier other than an adverb–adjective combination appears before a term, the compound modifier is often hyphenated to prevent misunderstanding, such as in American-football player or little-celebrated paintings. Without the hyphen, there is potential confusion about whether the writer means a "player of American football" or an "American player of football" and whether the writer means paintings that are "little celebrated" or "celebrated paintings" that are little.[20] Compound modifiers can extend to three or more words, as in ice-cream-flavored candy, and can be adverbial as well as adjectival (spine-tinglingly frightening). However, if the compound is a familiar one, it is usually unhyphenated. For example, some style guides prefer the construction high school students, to high-school students.[21][22] Although the expression is technically ambiguous ("students of a high school"/"school students who are high"), it would normally be formulated differently if other than the first meaning were intended. Noun–noun compound modifiers may also be written without a hyphen when no confusion is likely: grade point average and department store manager.[22]

When a compound modifier follows the term to which it applies, a hyphen is typically not used if the compound is a temporary compound. For example, "that gentleman is well respected", not "that gentleman is well-respected"; or "a patient-centered approach was used" but "the approach was patient centered."[23] But permanent compounds, found as headwords in dictionaries, are treated as invariable, so if they are hyphenated in the cited dictionary, the hyphenation will be used in both attributive and predicative positions. For example, "A cost-effective method was used" and "The method was cost-effective" (cost-effective is a permanent compound that is hyphenated as a headword in various dictionaries). When one of the parts of the modifier is a proper noun or a proper adjective, there is no hyphen (e.g., "a South American actor").[24]

When the first modifier in a compound is an adverb ending in -ly (e.g., "a poorly written novel"), various style guides advise no hyphen.[24][additional citation(s) needed] However, some do allow for this use. For example, The Economist Style Guide advises: "Adverbs do not need to be linked to participles or adjectives by hyphens in simple constructions ... Less common adverbs, including all those that end -ly, are less likely to need hyphens."[25] In the 19th century, it was common to hyphenate adverb–adjective modifiers with the adverb ending in -ly (e.g., "a craftily-constructed chair"). However, this has become rare. For example, wholly owned subsidiary and quickly moving vehicle are unambiguous, because the adverbs clearly modify the adjectives: "quickly" cannot modify "vehicle".

However, if an adverb can also function as an adjective, then a hyphen may be or should be used for clarity, depending on the style guide.[17] For example, the phrase more-important reasons ("reasons that are more important") is distinguished from more important reasons ("additional important reasons"), where more is an adjective. Similarly, more-beautiful scenery (with a mass-noun) is distinct from more beautiful scenery. (In contrast, the hyphen in "a more-important reason" is not necessary, because the syntax cannot be misinterpreted.) A few short and common words—such as well, ill, little, and much—attract special attention in this category.[25] The hyphen in "well-[past_participled] noun", such as in "well-differentiated cells", might reasonably be judged superfluous (the syntax is unlikely to be misinterpreted), yet plenty of style guides call for it. Because early has both adverbial and adjectival senses, its hyphenation can attract attention; some editors, due to comparison with advanced-stage disease and adult-onset disease, like the parallelism of early-stage disease and early-onset disease. Similarly, the hyphen in little-celebrated paintings clarifies that one is not speaking of little paintings.

Hyphens are usually used to connect numbers and words in modifying phrases. Such is the case when used to describe dimensional measurements of weight, size, and time, under the rationale that, like other compound modifiers, they take hyphens in attributive position (before the modified noun),[26] although not in predicative position (after the modified noun). This is applied whether numerals or words are used for the numbers. Thus 28-year-old woman and twenty-eight-year-old woman or 32-foot wingspan and thirty-two-foot wingspan, but the woman is 28 years old and a wingspan of 32 feet.[a] However, with symbols for SI units (such as m or kg)—in contrast to the names of these units (such as metre or kilogram)—the numerical value is always separated from it with a space: a 25 kg sphere. When the unit names are spelled out, this recommendation does not apply: a 25-kilogram sphere, a roll of 35-millimetre film.[27]

In spelled-out fractions, hyphens are usually used when the fraction is used as an adjective but not when it is used as a noun: thus two-thirds majority[a] and one-eighth portion but I drank two thirds of the bottle or I kept three quarters of it for myself.[28] However, at least one major style guide[26] hyphenates spelled-out fractions invariably (whether adjective or noun).

In English, an en dash, –, sometimes replaces the hyphen in hyphenated compounds if either of its constituent parts is already hyphenated or contains a space (for example, San Francisco–area residents, hormone receptor–positive cells, cell cycle–related factors, and public-school–private-school rivalries).[29] A commonly used alternative style is the hyphenated string (hormone-receptor-positive cells, cell-cycle-related factors). (For other aspects of en dash–versus–hyphen use, see Dash § En dash.)

Object–verbal-noun compounds

[edit]

When an object is compounded with a verbal noun, such as egg-beater (a tool that beats eggs), the result is sometimes hyphenated. Some authors do this consistently, others only for disambiguation; in this case, egg-beater, egg beater, and eggbeater are all common.

An example of an ambiguous phrase appears in they stood near a group of alien lovers, which without a hyphen implies that they stood near a group of lovers who were aliens; they stood near a group of alien-lovers clarifies that they stood near a group of people who loved aliens, as "alien" can be either an adjective or a noun. On the other hand, in the phrase a hungry pizza-lover, the hyphen will often be omitted (a hungry pizza lover), as "pizza" cannot be an adjective and the phrase is therefore unambiguous.

Similarly, a man-eating shark is nearly the opposite of a man eating shark; the first refers to a shark that eats people, and the second to a man who eats shark meat. A government-monitoring program is a program that monitors the government, whereas a government monitoring program is a government program that monitors something else.

Personal names

[edit]Some married couples compose a new surname (sometimes referred to as a double-barrelled name) for their new family by combining their two surnames with a hyphen. Jane Doe and John Smith might become Jane and John Smith-Doe, or Doe-Smith, for instance. In some countries only the woman hyphenates her birth surname, appending her husband's surname.

With already-hyphenated names, some parts are typically dropped. For example, Aaron Johnson and Samantha Taylor-Wood became Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Sam Taylor-Johnson. Not all hyphenated surnames are the result of marriage. For example Julia Louis-Dreyfus is a descendant of Louis Lemlé Dreyfus whose son was Léopold Louis-Dreyfus.

Hyphens are often used in romanization of Korean names, such as Ban Ki-moon and Cho Jung-ho.

Other compounds

[edit]Connecting hyphens are used in a large number of miscellaneous compounds, other than modifiers, such as in lily-of-the-valley, cock-a-hoop, clever-clever, tittle-tattle and orang-utan. Use is often dictated by convention rather than fixed rules, and hyphenation styles may vary between authors; for example, orang-utan is also written as orangutan or orang utan, and lily-of-the-valley may be hyphenated or not.

Suspended hyphens

[edit]

A suspended hyphen (also called a suspensive hyphen or hanging hyphen, or less commonly a dangling or floating hyphen) may be used when a single base word is used with separate, consecutive, hyphenated words that are connected by "and", "or", or "to". For example, short-term and long-term plans may be written as short- and long-term plans. This usage is now common and specifically recommended in some style guides.[22] Suspended hyphens are also used, though less commonly, when the base word comes first, such as in "investor-owned and -operated". Uses such as "applied and sociolinguistics" (instead of "applied linguistics and sociolinguistics") are frowned upon; the Indiana University style guide uses this example and says "Do not 'take a shortcut' when the first expression is ordinarily open" (i.e., ordinarily two separate words).[22] This is different, however, from instances where prefixes that are normally closed up (styled solidly) are used suspensively. For example, preoperative and postoperative becomes pre- and postoperative (not pre- and post-operative) when suspended. Some editors prefer to avoid suspending such pairs, choosing instead to write out both words in full.[26]

Other uses

[edit]A hyphen may be used to connect groups of numbers, such as in dates (see § Usage in date notation), telephone numbers or sports scores.

It can also be used to indicate a range of values, although many styles prefer an en dash (see Dash § En dash §§ Ranges of values).

It is sometimes used to hide letters in words (filleting for redaction or censoring), as in "G-d", although an en dash can be used as well ("G–d").[30]

It is often used in reduplication.[31]

Due to their similar appearances, hyphens are sometimes mistakenly used where an en dash or em dash would be more appropriate.[32]

Varied meanings

[edit]Some stark examples of semantic changes caused by the placement of hyphens to mark attributive phrases:

- Disease-causing poor nutrition is poor nutrition that causes disease.

- Disease causing poor nutrition is a disease that causes poor nutrition.

- A hard-working man is a man who works hard.

- A hard working man is a working man who is tough; however, this sense of hard is rarely used before other adjectives.

- A man-eating shark is a shark that eats humans.

- A man eating shark is a man who is eating shark meat.

- Three-hundred-year-old trees are an indeterminate number of trees that are each 300 years old.

- Three hundred-year-old trees are three trees that are each 100 years old.

- Three hundred year-old trees are 300 trees that are each a year old.

Use in computing

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

Hyphen-minuses

[edit]In the ASCII character encoding, the hyphen (or minus) is character 4510.[33] As Unicode is identical to ASCII (the 1967 version) for all encodings up to 12710, the number 4510 (2D16) is also assigned to this character in Unicode, where it is denoted as U+002D - HYPHEN-MINUS.[34] Unicode has, in addition, other encodings for minus and hyphen characters: U+2212 − MINUS SIGN and U+2010 ‐ HYPHEN, respectively. The unambiguous § "Unicode hyphen" at U+2010 is generally inconvenient to enter on most keyboards and the glyphs for this hyphen and the hyphen-minus are identical in most fonts (Lucida Sans Unicode is one of the few exceptions). Consequently, use of the hyphen-minus as the hyphen character is very common. Even the Unicode Standard regularly uses the hyphen-minus rather than the U+2010 hyphen.

The hyphen-minus has limited use in indicating subtraction; for example, compare 4+3−2=5 (minus) and 4+3-2=5 (hyphen-minus) — in most typefaces, the glyph for hyphen-minus will not have the optimal width, thickness, or vertical position, whereas the minus character is typically designed so that it does. Nevertheless, in many spreadsheet and programming applications the hyphen-minus must be typed to indicate subtraction, as use of the Unicode minus sign will not be recognised.

The hyphen-minus is often used instead of dashes or minus signs in situations where the latter characters are unavailable (such as type-written or ASCII-only text), where they take effort to enter (via dialog boxes or multi-key keyboard shortcuts), or when the writer is unaware of the distinction. Consequently, some writers use two or three hyphen-minuses (-- or ---) to represent an em dash.[35] In the TeX typesetting languages, a single hyphen-minus (-) renders a hyphen, a single hyphen-minus in math mode ($-$) renders a minus sign, two hyphen-minuses (--) renders an en dash, and three hyphen-minuses (---) renders an em dash.

The hyphen-minus character is also often used when specifying command-line options. The character is usually followed by one or more letters that indicate specific actions. Typically it is called a dash or switch in this context. Various implementations of the getopt function to parse command-line options additionally allow the use of two hyphen-minus characters, --, to specify long option names that are more descriptive than their single-letter equivalents. Another use of hyphens is that employed by programs written with pipelining in mind: a single hyphen may be recognized in lieu of a filename, with the hyphen then serving as an indicator that a standard stream, instead of a file, is to be worked with.

Soft and hard hyphens

[edit]Although software (hyphenation algorithms) can often automatically make decisions on when to hyphenate a word at a line break, it is also sometimes useful for the user to be able to insert cues for those decisions (which are dynamic in the online medium, given that text can be reflowed). For this purpose, the concept of a soft hyphen (discretionary hyphen, optional hyphen) was introduced, allowing such manual specification of a place where a hyphenated break is allowed but not forced. That is, it does not force a line break in an inconvenient place when the text is later reflowed.

Soft hyphens are inserted into the text at the positions where hyphenation may occur. It can be a tedious task to insert the soft hyphens by hand, and tools using hyphenation algorithms are available that do this automatically. Current modules[which?] of the Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) standard provide language-specific hyphenation dictionaries.

In contrast, a hyphen that is always displayed and printed is called a "hard hyphen". This can be a Unicode hyphen, a hyphen-minus, or a nonbreaking hyphen (see below). Confusingly, the term is sometimes limited to nonbreaking hyphens.[citation needed]

Nonbreaking hyphens

[edit]The word segmentation rules of most text systems consider a hyphen to be a word boundary and a valid point at which to break a line when flowing text. This is not always desirable, it could lead to ambiguity (e.g. retreat and re‑treat would be indistinguishable with a line break after re), it can split off an ending as in "n‑th" (though nth or "nth" could be used), and it is inappropriate in some languages other than English (e.g., a line break at the hyphen in Irish an t‑athair or Romanian s‑a would be undesirable). The non-breaking hyphen, nonbreaking hyphen, or no-break hyphen looks identical to the regular hyphen, but word processors do not break words at it. The nonbreaking space exists for similar reasons.

"Unicode hyphen"

[edit]Because the conventional hyphen-minus mark on keyboards is ambiguous (it can be interpreted – sometimes unexpectedly – as a hyphen or a minus, depending on context), in addition the Unicode consortium allocated codepoints for an unambiguous minus and an unambiguous hyphen. The Unicode hyphen (U+2010 ‐ HYPHEN) is seldom used. Even the Unicode Standard uses U+002D instead of U+2010 in its text.[36]

Use in date notation

[edit]Use of hyphens to delineate the parts of a written date (rather than the slashes used conventionally in Anglophone countries) is specified in the international standard ISO 8601. Thus, for example, 1789-07-14 is the standard way of writing the date of Bastille Day. This standard has been transposed as European Standard EN 28601 and has been incorporated into various national typographic style guides (e.g., DIN 5008 in Germany). Now all official European Union (and many member state) documents use this style. This is also the typical date format used in large parts of Europe and Asia, although sometimes with other separators than the hyphen.

This method has gained influence within North America, as most common computer file systems make the use of slashes in file names difficult or impossible. MS-DOS, OS/2 and Windows use / to introduce and separate switches to shell commands, and on both Windows and Unix-like systems slashes in a filename introduce subdirectories which may not be desirable. Besides encouraging use of dashes, the Y-M-D order and zero-padding of numbers less than 10 are also copied from ISO 8601 to make the filenames sort by date order.

Unicode

[edit]Unicode has multiple hyphen characters:[37]

- U+002D - HYPHEN-MINUS, a character of multiple uses

- U+00AD SOFT HYPHEN (­)[b]

- U+2010 ‐ HYPHEN (‐, ‐)

- U+2011 ‑ NON-BREAKING HYPHEN

- U+2E5D ⹝ OBLIQUE HYPHEN for medieval texts[38]

And in non-Latin scripts:[37]

- U+058A ֊ ARMENIAN HYPHEN

- U+05BE ־ HEBREW PUNCTUATION MAQAF

- U+1806 ᠆ MONGOLIAN TODO SOFT HYPHEN

- U+1B60 ᭠ BALINESE PAMENENG (used only as a line-breaking hyphen)

- U+2E17 ⸗ DOUBLE OBLIQUE HYPHEN (used in ancient Near-Eastern linguistics and in blackletter typefaces)

- U+30FB ・ KATAKANA MIDDLE DOT (has the Unicode property of "Hyphen" despite its name)

- U+FE63 ﹣ SMALL HYPHEN-MINUS (compatibility character for a small hyphen-minus, used in East Asian typography)

- U+FF0D - FULLWIDTH HYPHEN-MINUS (compatibility character for a wide hyphen-minus, used in East Asian typography)

- U+FF65 ・ HALFWIDTH KATAKANA MIDDLE DOT (compatibility character for a wide katakana middle dot, has the Unicode property of "Hyphen" despite its name)

Unicode distinguishes the hyphen from the general interpunct. The characters below do not have the Unicode property of "Hyphen" despite their names:[37]

- U+1400 ᐀ CANADIAN SYLLABICS HYPHEN

- U+2027 ‧ HYPHENATION POINT

- U+2043 ⁃ HYPHEN BULLET (⁃)

- U+2E1A ⸚ HYPHEN WITH DIAERESIS

- U+2E40 ⹀ DOUBLE HYPHEN

- U+30A0 ゠ KATAKANA-HIRAGANA DOUBLE HYPHEN

- U+10EAD 𐺭 YEZIDI HYPHENATION MARK

- U+10D6E GARAY HYPHEN

(See interpunct and bullet (typography) for more round characters.)

See also

[edit]- De-hyphenation – Concept in international relations

- Double hyphen – Historic punctuation mark (⹀)

- French orthography § Hyphens – Spelling and punctuation of the French language

- Hyphen War – Dispute over Czechoslovakia name after 1989

- Greek hyphen – Form of hyphen used in ancient Greek ("Papyrological hyphen")

- Enhypen – South Korean boy band, whose name refers to the hyphen

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b With numbers, where a plural noun would normally be used in an unhyphenated predicative position, the singular form of the noun is generally used in the hyphenated form used attributively. Thus a woman who is 28 years old becomes a 28-year-old woman. There are occasional exceptions to this general rule, for instance with fractions (a two-thirds majority) and irregular plurals (a two-criteria review, a two-teeth bridge).

- ^ The soft hyphen serves as an invisible marker that is used to specify a place in text where a hyphenated line break is preferred should one be needed. This avoids forcing a line break in an inconvenient place, should the text be reflowed. It becomes visible only if word wrapping occurs at the end of a line.

References

[edit]- ^ "Hyphen Definition". dictionary.com. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "American National Standard X3.4-1977: American Standard Code for Information Interchange" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 10 (4.2 Graphic characters).

- ^ ὑφέν. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "hyphen". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Nicolas, Nick. "Greek Unicode Issues: Punctuation Archived 6 August 2012 at archive.today". 2005. Accessed 7 October 2014.

- ^ Ελληνικός Οργανισμός Τυποποίησης [Ellīnikós Organismós Typopoíīsīs, "Hellenic Organization for Standardization"]. ΕΛΟΤ 743, 2η Έκδοση [ELOT 743, 2ī Ekdosī, "ELOT 743, 2nd ed."]. ELOT (Athens), 2001. (in Greek)

- ^ Keith Houston (2013). Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-393-06442-1.

- ^ Keith Houston (2013). Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-393-06442-1.

- ^ Wroe, Ann, ed. (2015). The Economist Style Guide (11th ed.). London / New York: Profile Books / PublicAffairs. p. 74.

hyphens There is no firm rule to help you decide which words are run together, hyphenated or left separate.

- ^ "Small object of grammatical desire". BBC News. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. 20 September 2007..

- ^ Gove, Philip Babcock (1993). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster. p. 14a, § 1.6.1. ISBN 978-0-87779-201-7. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Chambers, Allied (2006). The Chambers Dictionary. Allied Publishers. p. xxxviii, § 8. ISBN 978-8186062258. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Kromhout, Jan (2001). Afrikaans–English, English–Afrikaans Dictionary. Hippocrene Books. p. 182, § 5. ISBN 978-0-7818-0846-0. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Hartmann, R. Rf. K. (1986). The History of Lexicography: Papers from the Dictionary Research Centre Seminar at Exeter, March 1986. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-9027245236.

- ^ A fairly comprehensive list, although not exhaustive, is given at Prefix > List of English derivational prefixes.

- ^ "Hyphenated Words: A Guide", The Grammar Curmudgeon, City slide.

- ^ a b "Hyphens", Punctuation, Grammar book.

- ^ Liberman, Mark. "American Indian Hyphens". Language Log.

- ^ Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. The Song of Hiawatha.

- ^ Gary Blake and Robert W. Bly, The Elements of Technical Writing, p. 48. New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0020130856

- ^ E.g. "H". Bloomberg School Style Manual. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d E.g. "H". The IU editorial style guide. Indiana University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Davis, John (30 November 2004). "Using Hyphens in Compound Adjectives (and Exceptions to the Rule)" (Grammar tip). UHV. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Hyphenated Compound Words". englishplus.com. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ a b Wroe, Ann, ed. (2015). The Economist Style Guide (11th ed.). London / New York: Profile Books / PublicAffairs. pp. 77–78.

hyphens ... 12. Adverbs: Adverbs do not need to be linked to participles or adjectives by hyphens in simple constructions [examples elided]. But if the adverb is one of two words together being used adjectivally, a hyphen may be needed [examples elided]. The hyphen is especially likely to be needed if the adverb is short and common, such as ill, little, much and well. Less common adverbs, including all those that end -ly, are less likely to need hyphens [example elided].

- ^ a b c Iverson, Cheryl (2007). "8.3.1". AMA Manual of Style (10th ed.). Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517633-9.

- ^ Bureau international des poids et mesures, Le Système international d'unités (SI) / The International System of Units (SI), 9th ed. (Sèvres: 2019), ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, sub§5.4.3, p. 149; "Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)", NIST Special Publication 811, National Institute of Standards and Technology, March 2008.

- ^ American Psychological Association (APA) (2010), The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.), Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, ISBN 978-1-4338-0562-2.

- ^ Gary Lutz; Diane Stevenson (2005). The Writer's Digest grammar desk reference. Writer's Digest Books. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-58297-335-7.

- ^ Davidson, Baruch (23 February 2011). "Why Don't Jews Say G‑d's Name? - On the use of the word "Hashem" - Chabad.org". Chabad.org. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

It is customary to insert a dash in G-d's name when written or printed on a medium that could be defaced.

- ^ "Like vs. Like-Like: A Look at Reduplication in English". Dictionary.com. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Gunner, Jennifer (22 February 2010). "When and How To Use a Hyphen ( - )". grammar.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

Many people confuse hyphens and dashes because they look similar in printing.

- ^ Haralambous, Yannis (2007). "ASCII". Fonts & Encodings. O'Reilly Media. p. 29. ISBN 978-0596102425.

- ^ "3.1 General scripts" (PDF). Unicode Version 1.0 · Character Blocks. p. 30.

Loose vs. Precise Semantics. Some ASCII characters have multiple uses, either through ambiguity in the original standards or through accumulated reinterpretations of a limited codeset. For example, 27 hex is defined in ANSI X3.4 as apostrophe (closing single quotation mark; acute accent), and 2D hex as hyphen minus.

- ^ Bringhurst, Robert (2004). The elements of typographic style (third ed.). Hartley & Marks, Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-88179-206-5. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

In typescript, a double hyphen (--) is often used for a long dash. Double hyphens in a typeset document are a sure sign that the type was set by a typist, not a typographer. A typographer will use an em dash, three-quarter em, or en dash, depending on context or personal style. The em dash is the nineteenth-century standard, still prescribed in many editorial style books, but the em dash is too long for use with the best text faces. Like the oversized space between sentences, it belongs to the padded and corseted aesthetic of Victorian typography.

- ^ Korpela, Jukka K. (December 2020). "Dashes and hyphens". IT and Communication.

- ^ a b c "Unicode PropList.txt". 30 June 2025. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ Everson, Michael (12 January 2021). "L2/21-036 Proposal to add the Oblique Hyphen" (PDF). Retrieved 19 September 2022.

External links

[edit]- Wiktionary list of English phrases spelled with a hyphen

- Economist Style Guide—Hyphens

- Using hyphens in English; rules and recommendations

- Jukka Korpela, Soft hyphen (SHY)—a hard problem? (See also his article on word breaking, line breaks, and special characters (including hyphens) in HTML).

- Markus Kuhn, Unicode interpretation of SOFT HYPHEN breaks ISO 8859-1 compatibility. Unicode Technical Committee document L2/03-155R, June 2003.

- United States Government Printing Office Style Manual 2000 6. Compounding Rules]

Hyphen

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Linguistic origins and term evolution

The term hyphen derives from the Ancient Greek adverbial phrase hyph' hen (ὑφ’ ἕν), a contraction of hypò hén, meaning "under one" or "in one," which originally described the unification of separate linguistic elements such as words or syllables.[4] This etymology directly reflects the mark's function as a connector, emphasizing synthesis over separation, and traces to classical Greek grammatical practices where such joining was notated to clarify compound forms in prose and poetry.[7] The punctuation mark itself predates the specific term hyphen in Western scripts, with early prototypes appearing in Greek and Latin manuscripts as underlining or spacing indicators for linked syllables, but without standardized nomenclature until the Renaissance.[3] The word entered English lexicon in the 1620s via Late Latin hyphen, adopted during a period of revived interest in classical typography amid the spread of movable-type printing, which demanded explicit markers for line-end divisions and compounds.[4] Initial English usages, as recorded in contemporary dictionaries, applied hyphen strictly to the graphical dash-like symbol, distinguishing it from mere spacing or elision marks in handwritten texts.[8] Term evolution in English has been marked by semantic stability rather than radical shifts, retaining its core connotation of unity even as orthographic rules fluctuated; for instance, 18th- and 19th-century grammarians expanded hyphen to encompass verbal processes like "hyphenation" for word-breaking algorithms in typesetting, while debates over open versus closed compounds tested its boundaries without altering the root meaning.[9] This persistence aligns with causal developments in print standardization, where the term's Greek heritage facilitated its integration into technical lexicons, avoiding conflation with related marks like the dash, which evolved separately for interruption or emphasis.[3]Historical Development

Pre-printing era

The precursor to the hyphen originated in ancient Greek grammatical scholarship as a means to link words for unified pronunciation. Dionysius Thrax, a grammarian flourishing around 100 BC, devised a subscript tie mark (‿) placed beneath adjacent words to signify they formed a single phrase, particularly in poetic or compound contexts where separate reading would disrupt meter or meaning.[10] This innovation addressed challenges in scriptio continua, the continuous writing style of ancient Greek manuscripts lacking inter-word spaces, which required explicit cues for recitation and interpretation.[11] In medieval manuscripts, the device's role adapted to practical line-breaking needs as scribes introduced more consistent word spacing and justified text blocks. From the 8th century, hyphens or analogous strokes corrected misplaced separations or connected syllabic fragments divided at line ends, preserving phonetic integrity across pages.[12] By the 12th century in Greek copies, marginal linking strokes joined split syllables, while underlying hyphens appeared even in undivided words to guide readers.[13] Latin and vernacular European manuscripts followed suit, with the horizontal hyphen (-) emerging in English examples by the late 13th century exclusively for end-of-line breaks, rather than compounding.[14] These practices prioritized auditory flow in handwritten codices, where irregular line lengths demanded manual intervention absent mechanical justification.[15] Such markers varied by scribe and region, often subscript or abbreviated, reflecting ad hoc solutions to visual and vocal continuity before standardized typesetting.Adoption in early printing

![Gutenberg Bible page demonstrating early hyphenation][float-right]The hyphen's adoption in early printing marked a transition from irregular manuscript practices to standardized typographic conventions, enabling justified text blocks essential for aesthetic uniformity in printed books. Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the movable-type printing press, incorporated hyphenation into his production of the 42-line Bible, completed around 1455, to divide words at line ends and maintain even column widths mimicking high-end scribal layouts.[16] This innovation addressed the mechanical limitations of type composition, where fixed letter widths necessitated syllable breaks to avoid ragged right margins or excessive spacing.[17] In the Gutenberg Bible, hyphens appear frequently, often in clusters of multiple instances per line—sometimes four or more consecutively—to optimize justification under the constraints of hand-set type and limited ligature options.[18] Gutenberg adapted existing scribal techniques, such as marginal or sublinear marks for word division, into a consistent inline symbol cast in metal type, facilitating repeatable use across pages.[5] Early printers like those in Mainz and subsequent incunabula workshops rapidly emulated this approach, as evidenced by hyphenated breaks in works from the 1450s onward, which prioritized visual harmony over strict linguistic rules for syllable division.[19] The practice's utility in early presses stemmed from causal necessities of the technology: without automated kerning or variable spacing, hyphens minimized white space irregularities, a problem acute in double-column formats like the Bible's.[20] By the late 15th century, as printing spread across Europe, hyphenation became a core typographic tool, influencing the design of subsequent fonts and composition manuals, though variations persisted due to regional linguistic differences and compositor preferences.[21] This early adoption laid the groundwork for modern hyphen rules, prioritizing readability and page economy over verbatim manuscript fidelity.

Standardization in modern English

The standardization of hyphen usage in modern English emerged primarily through the development of authoritative style guides and dictionaries in the late 19th and 20th centuries, which sought to impose consistency amid evolving printing technologies and linguistic shifts. The Chicago Manual of Style, first published in 1906 by the University of Chicago Press, provided one of the earliest comprehensive frameworks for American English publishing, specifying hyphens for compound modifiers before nouns (e.g., "well-known author") and for avoiding ambiguity in prefixes like "re-entry," while advocating consultation of dictionaries for closed or open forms.[22] This manual emphasized empirical observation of usage frequency, reflecting a causal progression from ad hoc typesetting practices to rule-based systems that prioritized readability and uniformity in book production. Similarly, H.W. Fowler's A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926) influenced British English by critiquing excessive hyphenation as a "hyphen-hunter's" vice, promoting restraint except where clarity demanded it, such as in temporary compounds or to prevent misreading (e.g., "small-business owner").[23] Journalistic standards further shaped hyphenation, with the Associated Press (AP) Stylebook—evolving from early 20th-century wire service conventions—adopting a minimalist approach to reduce hyphens in familiar compounds, deeming them optional unless essential for clarity.[24] For instance, AP guidelines, updated as recently as 2019, omit hyphens in widely recognized phrases like "health care costs" when functioning as nouns, prioritizing brevity in news contexts over rigid compounding.[25] This reflects a broader 20th-century trend toward solid forms (e.g., "today" supplanting "to-day" by the mid-1900s), driven by dictionary precedents and the simplification enabled by mechanical and digital typesetting, which diminished reliance on manual syllable breaks.[26] Dictionaries like the Oxford English Dictionary played a pivotal role by documenting evolving preferences, with the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary eliminating approximately 16,000 hyphens in its 2007 edition to align with common usage in closed compounds such as "figleaf" and "pixie-led."[27] Despite these efforts, no universal standard exists, as rules vary between American and British conventions—British guides retaining more hyphens in adverbs like "re-enter" versus American tendencies toward openness—and across domains like academia (favoring Chicago or MLA) versus journalism (AP).[28] Modern software, including word processors with built-in hyphenation algorithms, enforces partial standardization by defaulting to dictionary-based breaks, but overrides persist for stylistic precision.[29] This patchwork, informed by usage data rather than prescriptive fiat, underscores causal realism in language evolution: hyphens persist where they resolve ambiguity or reflect historical compounding, but recede as familiarity solidifies word forms. Ongoing debates, such as in prefix attachments (e.g., "cooperate" versus "co-operate"), highlight the influence of institutional biases in editorial bodies, where conservative academies lag behind journalistic streamlining.[30]Primary Functions in Writing

Syllable division and line breaking

The hyphen functions primarily to divide words into syllables at the end of a line during typesetting or manual writing, enabling justified margins and preventing irregular spacing that disrupts visual uniformity.[31] This application, rooted in the need for even text blocks in printed materials, breaks a word only at natural syllable boundaries to preserve phonetic integrity and readability.[32] In English, such divisions align with spoken rhythms, though the language's irregular orthography often requires reference to standardized syllabification patterns rather than strict phonetic rules.[33] Syllable breaks for hyphenation follow established conventions: words divide between pronounced syllables, ideally at morphological junctures like prefixes, roots, or suffixes (e.g., "pre-historic" rather than "prehis-toric"), as these reflect etymological structure and reduce ambiguity.[33] Dictionaries denote permissible breaks with hyphens in pronunciation entries, guiding users to avoid invalid splits.[34] Prohibitions include dividing monosyllabic words, leaving fewer than two letters before or after the hyphen (e.g., not "a-bove" but "a-bove" is acceptable if syllabified as two syllables), or creating fragments ending in a single vowel or consonant cluster that defies pronunciation.[35][36] Practical constraints further refine usage: hyphenation should not occur on consecutive lines, proper nouns remain undivided to preserve identity, and breaks avoid awkward visual isolation of short remnants.[37] In professional typography, these rules minimize "rivers" of white space and enhance flow, with software algorithms approximating them via linguistic models trained on corpora of English texts.[38] Though digital word processors reduce manual need, precise control persists in book design and web CSS via soft hyphens (Unicode U+00AD), which render invisibly until a break is enforced.[39] Over-reliance on automatic hyphenation can introduce errors in edge cases, such as loanwords or neologisms, necessitating editorial verification against authoritative references.[40]Joining elements in compounds

Hyphens serve to connect two or more words or word elements into a compound that functions as a single unit, particularly when the compound precedes a noun as a modifier or when clarity requires it to prevent misreading. This usage clarifies relationships and avoids ambiguity, as in "small-business owner" where the hyphen links "small" and "business" to modify "owner" distinctly from "small business-owner."[41][42] In English orthography, such compounds may initially require hyphens during linguistic evolution before solidifying into closed forms like "notebook" from earlier "note-book."[43] Compound adjectives, or phrasal adjectives, typically demand hyphens when placed before the noun they describe, ensuring the elements are read as a cohesive descriptor; for instance, "a blue-eyed girl" versus the unhyphenated "the girl is blue eyed."[44] Exceptions occur with adverbs ending in "-ly," which do not take hyphens, as in "a highly motivated team," since the adverb modifies the adjective independently without forming a fused unit.[45][41] Hyphens also join compounds to avert confusion, such as "re-sign" (to sign again) distinct from "resign" (to quit).[46] Certain prefixes and suffixes consistently pair with hyphens to form compounds, including "ex-" for former status (e.g., "ex-husband"), "self-" for reflexive actions (e.g., "self-defense"), and "all-" or "great-" in multi-word constructions (e.g., "all-around," "great-grandmother").[45] Numbers in compounds follow suit, as in "twenty-one" or "three-fifths."[42] Style guides like those from Merriam-Webster recommend consulting dictionaries for established forms, noting that temporary or novel compounds—such as "COVID-19-related restrictions"—warrant hyphens until usage standardizes them otherwise.[41][47] In verbs derived from compounds, hyphens may persist or be omitted based on part of speech; for example, "ice skate" as open for the noun or verb, but "ice-skating rink" hyphenates the modifier.[48] Over time, frequent compounds transition: "to-day" became "today" by the early 20th century, reflecting conventionalization through print and usage data.[43][49] This joining function thus balances readability, tradition, and evolving norms, with inconsistencies arising across American and British English variants.[47]Handling prefixes, suffixes, and inflections

Hyphens connect prefixes to base words when clarity is at risk or spelling becomes awkward, such as with "re-" before a word starting with "re-" to distinguish re-cover (to cover again) from recover (to regain).[50] The prefix "ex-" (meaning former) always requires a hyphen, as in ex-husband, to avoid confusion with words like exist.[42] Similarly, "self-" and "all-" prefixes are hyphenated in compounds like self-control and all-encompassing, as are prefixes before capitalized terms or numerals, e.g., pro-American or post-1950.[51] Most other prefixes, including "anti-," "co-," "pre-," and "un-," form solid words without hyphens unless doubling vowels or consonants creates ambiguity, as in co-operate (though often closed as cooperate in American English).[45] Suffixes typically hyphenate with base words to denote temporary qualities or avoid misreading, such as -elect in mayor-elect or descriptive suffixes like -free in alcohol-free and -proof in waterproof (though the latter is often closed in established terms).[52] Hyphens prevent triple letters or awkward appearances, e.g., shell-like rather than shelllike.[53] In academic and formal writing, suffixes are closed unless the combination is novel or risks confusion, per guidelines favoring economy in established lexicon.[54] Inflections in words with prefixed or suffixed hyphens attach to the principal element, usually the base word at the end, to preserve semantic integrity. Plurals add -s or -es to that element, yielding forms like editors-in-chief (plural of editor-in-chief) or passers-by (plural of passer-by).[55] Possessives follow suit, placing the apostrophe on the inflected principal: daughter-in-law's opinion or courts-martial's rulings.[56] This rule holds for compounds involving prefixes or suffixes, as in ex-wives (plural of ex-wife) or sugar-frees (rare plural of sugar-free, though context often avoids such forms). Variations occur in open compounds, but hyphens signal the unit to guide inflection placement, reducing parsing errors in complex morphology. Style guides like Chicago emphasize consistency, closing inflections without additional hyphens unless clarity demands it, as in non-English speaker's guide.[57]Specialized Applications

Compound modifiers and attributive phrases

Compound modifiers, also known as compound adjectives or phrasal adjectives, consist of two or more words that function together as a single adjective modifying a noun.[58] These are typically hyphenated when placed before the noun to indicate they form a unified descriptive unit and to prevent misreading or ambiguity.[42] For instance, in "a blue-sky law," the hyphen links "blue-sky" to clarify it describes a type of legislation regulating securities speculation, rather than a law pertaining to a blue sky.[59] Without the hyphen, the phrase might imply separate modifiers, such as "blue" and "sky law," altering the intended meaning.[60] Hyphenation applies specifically in the attributive position, where the modifier precedes the noun it describes.[61] In contrast, the same compound is not hyphenated in the predicative position following the noun or linking verb.[42] Examples include: "The author is well known" (no hyphen after the verb) versus "a well-known author" (hyphenated before the noun).[60] This convention holds for adjective-noun, noun-noun, or adverb-adjective combinations, such as "high-level discussion" or "second-floor apartment."[61] Numerical compounds follow suit, with hyphens joining elements like "twenty-one-inch screen" to treat the phrase as a single modifier.[28] Exceptions exist to avoid unnecessary hyphens or awkwardness. Adverbs ending in "-ly" do not hyphenate with following adjectives, as in "highly effective method," because the adverbial form inherently links to the adjective without ambiguity.[62] Similarly, familiar phrases recognized as units, such as "high school student," may omit hyphens per certain styles if clarity is not compromised.[25] Style guides vary: The Chicago Manual of Style emphasizes hyphenation for clarity in pre-noun compounds but favors restraint overall, excluding "-ly" adverbs and post-noun modifiers.[22] The Associated Press Stylebook requires hyphens for compound modifiers aiding clarity but updated in 2019 to waive them for commonly understood phrases like "high school," prioritizing readability in journalism.[24] These differences reflect contextual priorities, with book publishing (Chicago) often more formal than news writing (AP).[63] Attributive phrases, encompassing multi-word modifiers in noun phrases, follow analogous rules to ensure the elements are parsed as a cohesive descriptor rather than independent terms.[64] For example, "cost-of-living adjustment" uses hyphens to bind the prepositional phrase attributively to "adjustment," avoiding confusion with separate costs or living adjustments.[65] Hyphenation in such cases is guided by ambiguity prevention: if omitting it could yield a different interpretation, the hyphen is retained, as in "man-eating shark" (predatory shark) versus "man eating shark" (shark being eaten by a man).[66] This practice traces to English's analytic structure, where hyphens compensate for the language's tendency toward ambiguity in juxtaposed modifiers without inflectional markers.[67]Usage in names and identifiers

Hyphens frequently join elements in compound personal names, particularly surnames formed by combining two family names, a practice common after marriage to preserve both partners' identities. This convention, known as a double-barreled or hyphenated surname, gained popularity in English-speaking countries during the 1980s and 1990s amid rising trends of women retaining maiden names.[68][69] For instance, in professional sports, the NBA recorded its first hyphenated player name in the 1960s, with the NFL following in the 1970s.[70] Hyphenation clarifies that the combined terms form a single unit, reducing ambiguity in legal and administrative contexts, though it can complicate forms and data entry due to length or system limitations.[71][72] In first names, hyphens link multiple given names treated as one, such as "Mary-Jane" or "Jean-Paul," originating from cultural traditions where parents select complementary elements for phonetic or familial reasons.[73] No universal grammatical rule mandates hyphenation in such names; usage depends on regional customs, personal preference, and orthographic standards, with some Hispanic naming practices incorporating hyphens between paternal and maternal surnames for citation accuracy.[74] For technical identifiers, hyphens serve in non-programming contexts like domain names, where they separate words (e.g., "my-domain.com") but cannot appear at the beginning or end per DNS rules, aiding readability without violating alphanumeric restrictions.[75] In file naming and CSS selectors, "kebab-case" (lowercase words joined by hyphens) enhances human readability, as in "user-profile.html," though it contrasts with snake_case using underscores.[76] Programming languages generally prohibit hyphens in variable or function identifiers to avoid interpreting them as subtraction operators, favoring alternatives like underscores or camelCase; for example, C restricts identifiers to letters, digits, and underscores.[77][78] This exclusion stems from syntactic parsing needs, with hyphens reserved for URLs or command-line arguments where separation improves clarity.[79]Numerical, fractional, and ranged expressions

In English orthography, hyphens connect the elements of spelled-out compound cardinal numbers from twenty-one to ninety-nine, as in "twenty-one" or "seventy-six," to form a single semantic unit.[80] Numbers above 99, such as one hundred one, typically omit the hyphen unless functioning as a compound modifier before a noun.[81] Ordinal compounds follow similar rules, hyphenating forms like twenty-first.[45] Fractions spelled out in words employ a hyphen between the numerator and denominator, particularly when the fraction acts as a modifier preceding a noun, as in "a one-half share" or "three-quarters full."[51] For simple fractions used as nouns, such as "one-half of the pie," hyphenation is standard in many guides, though some permit omission in standalone contexts.[82] Complex fractions with multi-word components, like "two and three-quarters," retain the hyphen only between the core fraction elements.[83] For ranged expressions involving numbers, hyphens appear in compound modifiers expressing spans, such as "five-to-ten-dollar fines" or "ten-to-twenty-year sentences," where the hyphen links the bounding terms into a unified descriptor.[84] Simple numeric ranges, like 10–20, conventionally use an en dash in style guides such as Chicago and MLA to denote spans without implying connection, though the Associated Press Stylebook permits or prefers a hyphen (10-20) in journalistic contexts for simplicity in typing and readability.[85][86] This distinction underscores the hyphen's role in compounding versus the en dash's for open ranges, with hyphen overuse in ranges often stemming from keyboard limitations rather than prescriptive rules.[87]Suspended hyphens and parallel constructions

Suspended hyphens, also termed suspensive hyphens, facilitate concise expression in parallel compound modifiers by omitting repeated elements that follow, connecting a series of terms sharing a common base or suffix while maintaining structural symmetry.[88] [89] This technique applies primarily to adjectival phrases before nouns, as in "small- and medium-sized enterprises," avoiding redundancy without altering meaning or parallelism.[45] The hyphen after the first modifier suspends to the subsequent ones, joined by "and" before the final item, ensuring the construction remains balanced and readable.[90] In practice, suspended hyphens link modifiers with repeated suffixes, such as "first- and second-degree burns," or prefixes, like "pre- and post-operative care."[88] For numerical or ordinal series, examples include "10-, 20-, and 30-year bonds" or "19th- and 20th-century art," where the hyphen signals the implied repetition of the unit.[91] This parallels the grammatical form across items, aligning with principles of coordinate structure that demand equivalent phrasing for clarity and rhythm in lists.[92] Major style guides endorse this for efficiency: The Chicago Manual of Style (section 7.89) permits suspended hyphens in such compounds to prevent awkward repetition, while the AP Stylebook similarly advises their use in parallel attributives.[22] [90] Parallel constructions benefit particularly in technical or legal writing, where precision demands symmetry, as in "investor- and employee-owned firms," mirroring the modifier-noun pattern without verbose expansion.[89] However, not all guides favor them universally; the Microsoft Style Guide recommends spelling out full phrases like "left-aligned and right-aligned text" over suspended forms unless space constraints apply, prioritizing explicitness over brevity.[93] Care must be taken to avoid ambiguity: the suspended element must clearly apply to all prior terms, and en dashes may substitute for hyphens when the repeated part is an open compound, per Chicago (6.80), as in "New and old-style options."[22] Empirical editing practice shows suspended hyphens reduce word count by up to 20% in dense lists while preserving parallelism, though overuse can disrupt flow if the omission confuses readers unfamiliar with the convention.[94]Cross-Linguistic and Contextual Uses

Variations in non-English languages

In German, compound nouns are generally formed by concatenating words without hyphens, as in Kindergarten (children's garden) rather than Kinder-garten, reflecting a orthographic preference for fusion to create single lexical units; hyphens are reserved for rare cases of ambiguity prevention, prefixes like ex- or non-, or syllabic breaks at line ends, where rules prohibit splitting within syllables or before certain consonants.[95][96] This contrasts with English's frequent hyphenation of temporary compounds, as German prioritizes readability through long fused words, with official rules from the Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung discouraging hyphens except where fusion would obscure meaning.[97] French employs hyphens more liberally than English, particularly in compound adjectives, numerals (e.g., vingt-et-un for 21), dates (e.g., le 1er-juin), and inverted question forms (e.g., Aimez-vous...?), as well as in geographic compounds like Saint-Germain-des-Prés; the 1990 spelling reform mandated hyphens in all compound numbers under 100 lacking et, though traditionalists sometimes omit them.[98][99] This extensive use underscores French's emphasis on liaison and euphony, with hyphens facilitating pronunciation cues absent in fused forms common in neighboring languages like German. In Spanish, hyphens primarily link words of equal grammatical status to form compounds, such as azul-gris (blue-gray) or vicepresidente (vice president, though often fused), and are required for certain prefixes (e.g., anti- before vowels), foreign terms, or to avoid cacophony; the Real Academia Española's orthographic norms limit their role compared to French, favoring fusion or spaces in many adjectival phrases.[100] Line-end hyphenation follows phonetic syllables, but overall usage is sparser, reflecting Spanish's phonetic transparency and avoidance of visual clutter. Italian restricts hyphens to occasional joins in compound terms (e.g., italiano-francese for Italian-French), line breaks guided by rules like avoiding splits before "s" followed by dissimilar consonants (e.g., pre-sto, not pres-to), and prefixes in neologisms; unlike English's phrasal hyphens, Italian prefers separate words or fusion for nouns, aligning with Romance language tendencies toward morphological clarity without frequent punctuation intervention.[101][102] Across these languages, hyphenation patterns reveal causal links to phonological structures—syllabic in Romance for euphony, fusional in Germanic for lexical economy—differing from English's etymological and syntactic flexibility.[103]Role in dates, times, and scores

In standardized numerical date formats, such as the ISO 8601 specification, the hyphen serves as a delimiter between the year, month, and day components, yielding representations like 2025-10-25 for October 25, 2025.[104] This usage ensures unambiguous parsing in data interchange and computing contexts, where hyphens provide a consistent separator shorter than spaces or slashes.[105] For date ranges in prose, while typographic conventions favor the en dash (e.g., 2020–2025), hyphens are commonly substituted in informal or keyboard-limited writing due to their accessibility on standard layouts, though this can blur distinctions from compound words.[106] Hyphens appear in time expressions primarily through informal range notations, such as 9:00-5:00 for business hours, where they approximate the "to" relation despite formal preferences for en dashes in ranges (e.g., 9:00–5:00).[107] This substitution arises from practical constraints in digital input, as hyphens are ubiquitous on keyboards, but it deviates from guidelines emphasizing en dashes for spans to avoid confusion with hyphens in compounds like "nine-to-five."[106] In 24-hour formats or timestamps, hyphens rarely delimit hours and minutes, which instead use colons (e.g., 14:30), but may connect time ranges in schedules or logs.[108] For scores, particularly in sports reporting, the hyphen conventionally separates the points or tallies of opposing sides, as in a 34-6 win, reflecting a longstanding practice in published journalism where hyphens predominate over en dashes for such oppositions.[109] This usage conveys "versus" or "to" without spaces, aligning with brevity in headlines and box scores; for instance, Associated Press style endorses hyphens for game results like 10-6 records.[110] Although en dashes can denote ranges in scores theoretically, empirical observation of print and digital media shows hyphens as the norm, prioritizing readability and tradition over strict typographic hierarchy.[111]Technical Representations

Typographic distinctions from dashes

The hyphen (‐), en dash (–), and em dash (—) represent distinct glyphs in professional typography, differentiated by relative widths, visual design, and rendering behaviors to ensure optimal spacing and readability. The hyphen is the narrowest and often thickest of the three, with a height and stroke width calibrated to align seamlessly between letters or words in compound forms, avoiding undue line disruption; its design prioritizes inline connectivity over interruption. In contrast, the en dash spans roughly the width of a capital "N" (one en unit, typically half an em), while the em dash matches the width of a capital "M" (one em unit), enabling them to function as spacers or emphatic breaks with appropriate kerning in composed text. These proportions trace to 19th-century metal type systems, where em and en served as foundational measurement units for justifying lines and inserting punctuation without reflow issues.[112][113][114]| Glyph | Name | Unicode Code Point | Relative Width (in em units) | Design Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Hyphen-minus | U+002D | ~0.4–0.5 em | Shortest, lowest optical center; substitutes for all in ASCII but lacks dash-specific kerning. [115][116] |

| – | En dash | U+2013 | 1 en (~0.5 em) | Horizontal stroke; thinner than hyphen in many fonts for range indications. [116][117] |

| — | Em dash | U+2014 | 1 em | Widest, often unspaced; provides abrupt visual pause in sentence structure. [116][118] |

Computing implementations and variants

In computing, the hyphen is primarily represented by the hyphen-minus character (U+002D in Unicode, ASCII 45), which serves multiple roles including word division, subtraction, and informal dashes due to historical limitations in early character sets like ASCII that lacked distinct glyphs for each function.[121] This multifunctionality can lead to rendering inconsistencies across fonts and systems, where the glyph's width and spacing vary but remains shorter than en or em dashes.[122] Key variants address specific needs in text processing: the soft hyphen (U+00AD), an invisible control character that suggests a potential line-break point without displaying unless the word wraps there, enabling discretionary hyphenation in typesetting software; the non-breaking hyphen (U+2011), which prevents line breaks while visibly rendering as a hyphen, useful for compound terms like "pre-requisite" that must stay intact; and the figure dash (U+2012), a variant aligned with numeral widths for ranges in numeric contexts.[123][124] These variants, defined in Unicode standards, allow precise control over layout but require explicit insertion, as automatic substitution varies by application— for instance, Microsoft Word supports optional (soft) and non-breaking hyphens via keyboard shortcuts like Ctrl+Shift+- and Ctrl+-, respectively.[123] Hyphenation implementations in word processors and layout engines typically rely on algorithms to insert soft hyphens for justified text. Rule-based systems apply linguistic patterns, such as TeX's 1977 algorithm by Frank Liang, which uses hyphenation patterns (strings of letters with break codes) to identify valid syllable divisions efficiently across languages, processing words via trie-based matching for O(n time complexity where n is word length.[125] Dictionary-based approaches, common in tools like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice, cross-reference words against precomputed exception lists for accuracy, falling back to rules for unknowns, though they demand larger memory footprints—TeX's patterns, for example, total around 250 KB for English.[126] Hybrid methods combine both, as in modern CSS via thehyphens property, which supports auto mode for browser engines like WebKit or Blink to apply language-specific rules (e.g., lang="en" triggers English patterns), manual for explicit soft hyphens, or none to disable.[127]

In web and identifier contexts, hyphens function differently: URLs treat them as word separators for SEO, with Google indexing hyphen-delimited terms as distinct keywords (e.g., "multi-word-url" parses as "multi" "word" "url"), outperforming underscores which are ignored as connectors per crawling guidelines updated as of 2023.[128] Programming languages restrict hyphens in identifiers—Python and JavaScript prohibit them in variable names to avoid operator confusion (e.g., a-b subtracts), favoring underscores or camelCase, while domain names and CSS class selectors permit hyphens freely for readability.[129] These conventions stem from lexical parsers prioritizing unambiguous tokenization, with hyphens often escaped or disallowed in regex patterns to prevent misinterpretation as range operators.[130]

Unicode encoding and standards

In the Unicode Standard, the primary character for the hyphen in compound words and syllabification is U+2010 HYPHEN, defined in the General Punctuation block as a narrow connector used specifically for hyphenation without the multifunctional attributes of legacy encodings.[131] This contrasts with U+002D HYPHEN-MINUS from the Basic Latin block, which originated in ASCII (as code 2D hexadecimal) and serves interchangeably as a hyphen, minus sign, or dash surrogate due to its widespread keyboard availability and backward compatibility, though it is wider and less semantically precise for typographic hyphenation.[132][131] For line-breaking purposes, U+00AD SOFT HYPHEN (in the Latin-1 Supplement block) functions as an invisible control character that suggests an optional word break point, rendering a visible hyphen only if the line breaks there, as specified in Unicode's core specification for format characters.[133][134] Complementing this, U+2011 NON-BREAKING HYPHEN (also in General Punctuation) provides a visible hyphen that prevents line breaks, ensuring continuity in phrases like number ranges or compound terms, per Unicode's guidelines on nonbreaking characters.[135][131] Unicode Annex #14 outlines the Line Breaking Algorithm, assigning properties such as "BA" (break after) to U+002D and U+2010 for enabling hyphenation in justified text, while treating U+00AD as a dictionary-based hyphenation cue integrated with language-specific rules in implementations like those for German or Finnish, where long compounds benefit from precise breaks.[136] Normalization forms (NFC/NFD) under Unicode Standard Annex #15 preserve these distinctions, though legacy systems often map U+002D to all hyphen-like uses, leading to recommendations in the standard for semantic tagging over visual substitution in modern typography.[137] The Unicode Consortium maintains these encodings across versions, with no deprecation of U+002D despite its ambiguities, to support global text processing interoperability.Debates, Variations, and Empirical Insights

Differences across style guides

Style guides for English-language writing prescribe rules for hyphenation that vary based on context, audience, and evolving conventions, with journalism-oriented guides like the AP Stylebook favoring brevity and minimal punctuation, while book-publishing and academic guides such as the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), APA Publication Manual, and MLA Handbook retain more hyphens to prevent ambiguity.[138][139] These divergences arise from differing priorities: AP emphasizes readability in fast-paced news, often eliminating hyphens in familiar compounds, whereas CMOS provides exhaustive lists for clarity in complex prose.[140][141] In compound modifiers (adjectival phrases before a noun), all major guides recommend hyphens to avoid misreading—e.g., "small-business owner" rather than "small business owner," which could imply a diminutive enterprise—but application differs in edge cases. APA specifies hyphenation for compounds expressing a single idea or prone to misinterpretation, such as "high-level discussion."[142] CMOS extends this to temporary or unfamiliar compounds, like "AI-generated content," while advising against it after the noun (e.g., "the owner is small business").[143] AP aligns but trends toward openness in established terms, omitting hyphens where context suffices.[94] MLA follows CMOS closely for literary contexts, prioritizing precision in descriptive phrases.[138] Prefix compounds show sharper contrasts, particularly with common prefixes like pre-, post-, re-, and co-. The AP Stylebook, updated in 2024, generally omits hyphens unless clarity demands it (e.g., "re-treat" vs. "retreat"), resulting in solid words like "pregame," "postgame," and "coauthor."[94][140] CMOS, by contrast, hyphenates prefixes before capitalized words or numerals (e.g., "pre-1900") and in cases of potential confusion, such as "re-cover" (to cover again) versus "recover."[22] APA mirrors CMOS for scientific writing, hyphenating prefixes with proper nouns (e.g., "non-U.S.") to maintain readability in technical compounds.[142] Oxford style, influential in British English, often retains hyphens more conservatively than AP but aligns with CMOS on ambiguity, such as "co-operate."[144] For numerical expressions, hyphenation of spelled-out compounds like "twenty-one" or fractions like "one-half" is uniform across guides when spelled out, but ranges highlight typographic splits: AP employs the hyphen for spans (e.g., "pages 10-12" or "1990-2025"), substituting for the en dash to simplify keyboarding in news contexts.[86] CMOS, APA, and MLA mandate the en dash for ranges (e.g., 10–12), reserving the hyphen strictly for word division or compounds, a distinction rooted in precise typographic tradition over journalistic expediency.[145][86]| Aspect | Chicago Manual of Style | AP Stylebook | APA Publication Manual | MLA Handbook |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefixes (e.g., co-) | Hyphenate for clarity or before capitals/numerals (e.g., co-author if ambiguous) | Generally solid (e.g., coauthor); exceptions for clarity (e.g., co-op) | Hyphenate if misreading possible (e.g., non-U.S.) | Aligns with CMOS; case-by-case for literary compounds |

| Ranges | En dash (e.g., 10–12) | Hyphen (e.g., 10-12) | En dash (e.g., 10–12) | En dash (e.g., 10–12) |

| Compound modifiers | Hyphenate before noun if temporary/unfamiliar; open after | Hyphenate only if needed for clarity; prefers open in familiar cases | Hyphenate before noun for single idea or ambiguity | Hyphenate attributive compounds; follows CMOS detail |