Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

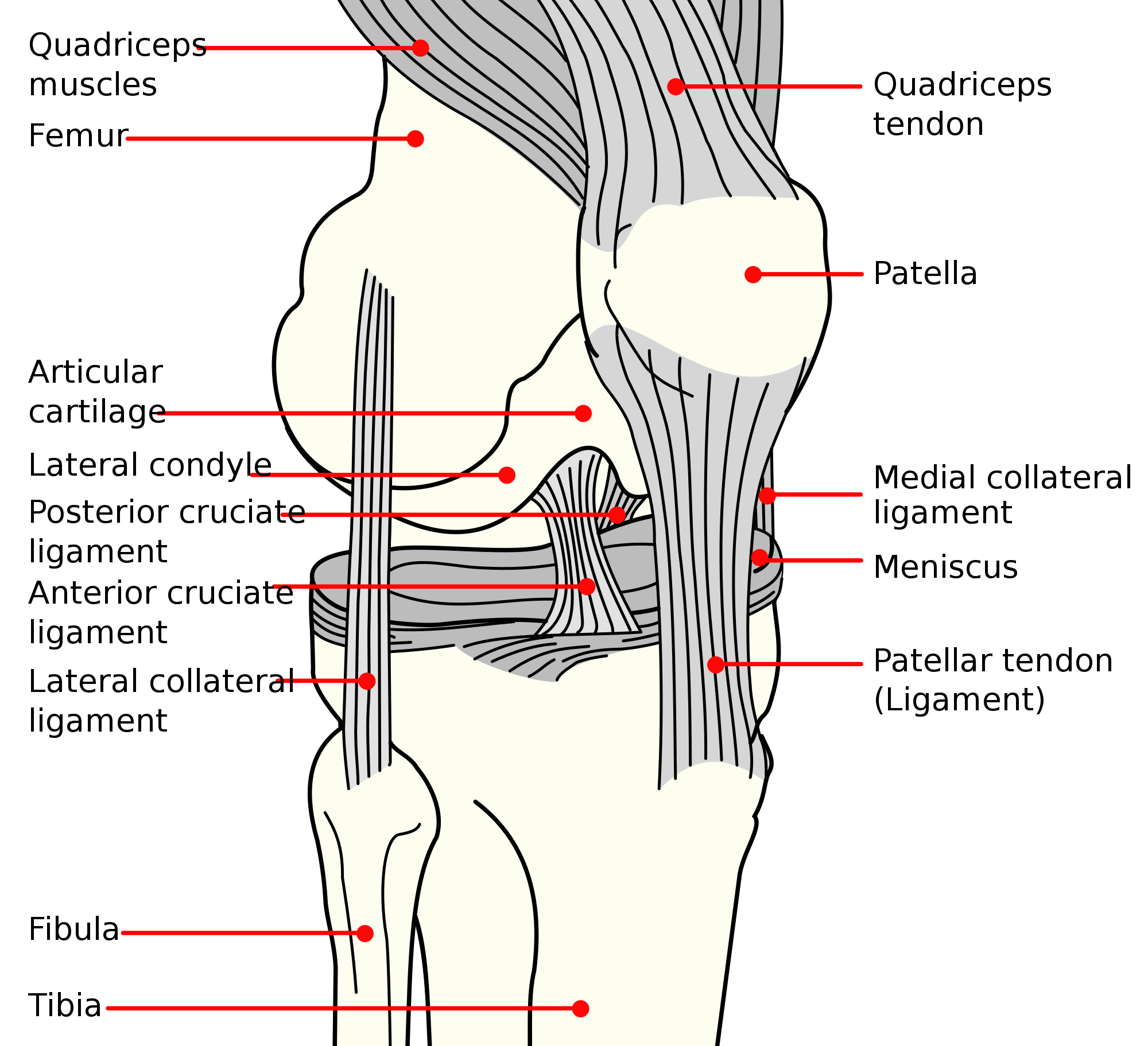

Anterior cruciate ligament injury

View on Wikipedia| Anterior Cruciate Ligament injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram of the right knee | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Audible "crack" with pain, knee instability, swelling of knee[1] |

| Causes | Non-contact injury, contact injury[2] |

| Risk factors | Athletes, females[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical exam, MRI[1] |

| Prevention | Neuromuscular training,[3] core strengthening[4] |

| Treatment | Braces, physical therapy, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | c. 200,000 per year (US)[2] |

An anterior cruciate ligament injury occurs when the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is either stretched, partially torn, or completely torn.[1] The most common injury is a complete tear.[1] Symptoms include pain, an audible cracking sound during injury, instability of the knee, and joint swelling.[1] Swelling generally appears within a couple of hours.[2] In approximately 50% of cases, other structures of the knee such as surrounding ligaments, cartilage, or meniscus are damaged.[1]

The underlying mechanism often involves a rapid change in direction, sudden stop, landing after a jump, or direct contact to the knee.[1] It is more common in athletes, particularly those who participate in alpine skiing, football (soccer), netball, American football, or basketball.[1][5] Diagnosis is typically made by physical examination and is sometimes supported and confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[1] Physical examination will often show tenderness around the knee joint, reduced range of motion of the knee, and increased looseness of the joint.[2]

Prevention is by neuromuscular training and core strengthening.[3][4] Treatment recommendations depend on desired level of activity.[1] In those with low levels of future activity, nonsurgical management including bracing and physiotherapy may be sufficient.[1] In those with high activity levels, surgical repair via arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is often recommended.[1] This involves replacement with a tendon taken from another area of the body or from a cadaver.[2] Following surgery rehabilitation involves slowly expanding the range of motion of the joint, and strengthening the muscles around the knee.[1] Surgery, if recommended, is generally not performed until the initial inflammation from the injury has resolved.[1] It should also be taken into precaution to build up as much strength in the muscle that the tendon is being taken from to reduce risk of injury[clarification needed].

About 200,000 people are affected per year in the United States.[2] In some sports, women have a higher risk of ACL injury, while in others, both sexes are equally affected.[5][6][7] While adults with a complete tear have a higher rate of later knee osteoarthritis, treatment strategy does not appear to change this risk.[8] ACL tears can also occur in some animals, including dogs.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]When an individual has an ACL injury, they are likely to hear a "pop" in their knee followed by pain and swelling. They may also experience instability in the knee once they resume walking and other activities, as the ligament can no longer stabilize the knee joint and keep the tibia from sliding forward.[9]

Reduced range of motion of the knee and tenderness along the joint line are also common signs of an acute ACL injury. The pain and swelling may resolve on its own; however, the knee will remain unstable and returning to sport without treatment may result in further damage to the knee.[1]

Causes

[edit]

Tearing occurs when the tibia moves too far forwards or the femur moves too far backwards.[10] Causes may include:

- Changing direction rapidly (also known as "cutting")

- Landing from a jump awkwardly

- Coming to a sudden stop when running

- A direct contact or collision to the knee (e.g. during a football tackle or a motor vehicle collision)[1]

These movements cause the tibia to shift away from the femur rapidly, placing strain on the knee joint and potentially leading to rupture of the ACL. About 80% of ACL injuries occur without direct trauma.[11] Risk factors include female anatomy, specific sports, poor conditioning, fatigue, and playing on a turf field.[9]

Injuries to the ACL are common, 250,000 ACL injuries occur on an annual basis. This corresponds to a 1 in 3,000 chance of an individual sustaining an ACL injury. Ligaments in the ACL or meniscus are usually torn with an external force being applied to the knee joint. The ACL can be torn without an external force being applied[12]

Female predominance

[edit]Female athletes are two to eight times more likely to strain their ACL in sports that involve cutting and jumping as compared to men who play the same particular sports.[13] NCAA data has found relative rates of injury per 1000 athlete exposures as follows:[citation needed]

- Men's basketball 0.07, women's basketball 0.23

- Men's lacrosse 0.12, women's lacrosse 0.17

- Men's football 0.09, women's football 0.28

The highest rate of ACL injury in women occurred in gymnastics, with a rate of injury per 1000 athlete exposures of 0.33. Of the four sports with the highest ACL injury rates, three were women's – gymnastics, basketball and soccer.[14]

Differences between males and females identified as potential causes are the active muscular protection of the knee joint, differences in leg/pelvis alignment, and relative ligament laxity caused by differences in hormonal activity from estrogen and relaxin.[13][15] Birth control pills also appear to decrease the risk of ACL injury.[16]

Dominance theories

[edit]

Some studies have suggested that there are four neuromuscular imbalances that predispose women to higher incidence of ACL injury. Female athletes are more likely to jump and land with their knees relatively straight and collapsing in towards each other, while most of their bodyweight falls on a single foot and their upper body tilts to one side.[17] Several theories have been described to further explain these imbalances. These include the ligament dominance, quadriceps dominance, leg dominance, and trunk dominance theories.[citation needed]

The ligament dominance theory suggests that when females athletes land after a jump, their muscles do not sufficiently absorb the impact of the ground. As a result, the ligaments of the knee must absorb the force, leading to a higher risk of injury.[18] Quadriceps dominance refers to a tendency of female athletes to preferentially use the quadriceps muscles to stabilize the knee joint.[18] Given that the quadriceps muscles work to pull the tibia forward, an overpowering contraction of the quadriceps can place strain on the ACL, increasing risk of injury.[citation needed]

Leg dominance describes the observation that women tend to place more weight on one leg than another.[19] Finally, trunk dominance suggests that males typically exhibit greater control of the trunk in performance situations as evidenced by greater activation of the internal oblique muscle.[18] Female athletes are more likely to land with their upper body tilted to one side and more weight on one leg than the other, therefore placing greater rotational force on their knees.[20]

Governments and healthcare professionals acknowledge the high incidence of ACL injuries and have dedicated significant research efforts to prevention and rehabilitation. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of diverse training methods, such as balance, plyometric, resistance, and technique training, in reducing ACL injury risk among adolescent females. However, evidence supporting this approach for adult sport-active populations, both male and female, is limited. Two underdeveloped areas are the specificity of exercises used in interventions and the consideration of athletes' experiences, including adherence and motivation. Therefore, there is a need for injury prevention researchers to optimize training content and delivery methods to better translate research findings for diverse sport populations of varying ages and genders.[21]

Hormonal and anatomic differences

[edit]Before puberty, there is no observed difference in frequency of ACL tears between the sexes. Changes in sex hormone levels, specifically elevated levels of estrogen and relaxin in females during the menstrual cycle, have been hypothesized as causing predisposition of ACL ruptures. This is because they may increase joint laxity and extensibility of the soft tissues surrounding the knee joint.[13] Ongoing research has observed a greater occurrence of ACL injuries in females during ovulation and fewer injuries during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle.[22]

Study results have shown that female collegiate athletes with concentration levels of relaxin that are greater than 6.0 pg/mL are at four times higher risk of an ACL tear than those with lower concentrations.[23]

Relaxin is increased when estrogen levels are increased during the female menstrual cycle.[24] Estrogen is at its peak just before ovulation, which makes it fall into the follicular phase of the mensural cycle. These hormonal rises often fall within a 2-3 day period of an increase in knee laxity. These times of increased estrogen concentration are subsequently related to times of reduced tendon strength and stability.[25] Additionally, the use of hormonal medication such as birth control may fluctuate the window and level of laxity which should be monitored. The NHI, found that the use of hormonal oral contraceptives reduced the risk of tearing by 68%.[26] Moreover, women are more likely to face an ACL tear or injury when they are experiencing elevated levels of estrogen or progesterone. During these times, females don't necessarily need to limit their activity levels out of fear or precaution but it is beneficial if they participate in the proper warm-ups or strengthening exercises to limit potential risks.

Additionally, female pelvises widen during puberty through the influence of sex hormones. This wider pelvis requires the femur to angle toward the knees. This angle towards the knee is referred to as the Q angle. The average Q angle for men is 14 degrees and the average for women is 17 degrees. Steps can be taken to reduce this Q angle, such as using orthotics.[27] The relatively wider female hip and widened Q angle may lead to an increased likelihood of ACL tears in women.[28]

ACL, muscular stiffness, and strength

[edit]During puberty, sex hormones also affect the remodeled shape of soft tissues throughout the body. The tissue remodeling results in female ACLs that are smaller and will fail (i.e. tear) at lower loading forces, and differences in ligament and muscular stiffness between men and women. Women's knees are less stiff than men's during muscle activation. Force applied to a less stiff knee is more likely to result in Aitsears.[29]

In addition, the quadriceps femoris muscle is an antagonist to the ACL. According to a study undertaken on female athletes at the University of Michigan, 31% of female athletes recruited the quadriceps femoris muscle first as compared to 17% in males. Because of the elevated contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle during physical activity, an increased strain is placed onto the ACL due to the "tibial translation anteriorly".[30]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The knee joint is formed by three bones: the femur (thighbone), the tibia (shinbone), and the patella (kneecap). These bones are held together by ligaments, which are strong bands of tissue that keep the joint stable while an individual is walking, running, jumping, etc. There are two types of ligaments in the knee: the collateral ligaments and the cruciate ligaments.[citation needed]

The collateral ligaments include the medial collateral ligament (along the inside of the knee) and the lateral or fibular collateral ligament (along the outside of the knee). These two ligaments function to limit sideways movement of the knee.[2]

The cruciate ligaments form an "X" inside the knee joint with the anterior cruciate ligament running from the front of the tibia to the back of the femur, and the posterior cruciate ligament running from the back of the tibia to the front of the femur. The anterior cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur and provides rotational stability.[2]

There are also two C-shaped structures made of cartilage called the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus that sit on top of the tibia in the knee joint and serve as cushion for the bones.[1]

|

|

| Right knee, front, showing interior ligaments | Left knee, behind, showing interior ligaments |

Diagnosis

[edit]Manual tests

[edit]Most ACL injuries can be diagnosed by examining the knee and comparing it to the other, non-injured knee. When a doctor suspects ACL injury in a person who reports a popping sound in the knee followed by swelling, pain, and instability of the knee joint, they can perform several tests to evaluate the damage to the knee. These tests include the pivot-shift test, anterior drawer test, and Lachman test. The pivot-shift test involves flexing the knee while holding onto the ankle and slightly rotating the tibia inwards.[31] In the anterior drawer test, the examiner flexes the knees to 90 degrees, sits on the person's feet, and gently pulls the tibia towards themself.[32] The Lachman test is performed by placing one hand on the person's thigh and the other on the tibia and pulling the tibia forward.[33] These tests are meant to test whether the ACL is intact and therefore able to limit the forward motion of the tibia. The Lachman test is recognized by most authorities as the most reliable and sensitive of the three.[34]

Technological innovations like stop-action photography, force platforms, and programmable computers have propelled biomechanics into a key research area within the human sciences. Advances in motion capture, musculoskeletal modeling, and human simulation have deepened our understanding of the mechanical causes of musculoskeletal injuries and diseases. However, measuring force at joint, muscle, tendon, and articular surfaces, especially in the knee, is complex and relies heavily on intricate modeling of motion capture and medical imaging data. This complexity has limited the involvement of biomechanists in designing, implementing, and evaluating prophylactic training interventions and neuromuscular rehabilitation programs.[35]

Medical imaging

[edit]

Though clinical examination in experienced hands can be accurate, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, which provides images of the soft tissues like ligaments and cartilage around the knee.[1] It may also permit visualization of other structures which may have been coincidentally involved, such as the menisci or collateral ligaments.[36] An x-ray may be performed in addition to evaluate whether one of the bones in the knee joint was broken during the injury.[9]

MRI is perhaps the most used technique for diagnosing the state of the ACL, but it is not always the most reliable technique as the ACL can seem healed on chronic cases with the proliferation of synovial scar tissue when treated conservatively.[37]

MRI is particularly useful in cases of partial tear of the ACL. The anteromedial band is most commonly injured compared to the posterolateral band.[38]

Arthrometers/Laximeters

[edit]Another form of evaluation that may be used in case physical examination and MRI are inconclusive is laximetry testing (i.e. arthrometry and stress imaging), which involve applying a force to the leg and quantifying the resulting displacement of the knee.[39] These medical devices basically replicate manual tests but offer objective assessments.[40] The GNRB arthrometer, for example, is a knee arthrometer that is considered more effective than the Lachman test.[41]

Classification

[edit]An injury to a ligament is called a sprain. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons defines ACL injury in terms of severity and classifies them as Grade 1, 2, or 3 sprains.[1] Grade 1 sprains occur when the ligament is stretched slightly but the stability of the knee joint is not affected. Grade 2 sprains occur when the ligament is stretched to the point that it becomes loose; this is also referred to as a partial tear. Grade 3 sprains occur when the ligament is completely torn into two pieces, and the knee joint is no longer stable. This is the most common type of ACL injury.[citation needed]

Around half of ACL injuries occur in conjunction with injury to other structures in the knee, including the other ligaments, menisci, or cartilage on the surface of the bones. A specific pattern of injury called the "unhappy triad" (also known as the "terrible triad," or "O'Donoghue's triad") involves injury to the ACL, MCL, and medial meniscus, and occurs when a lateral force is applied to the knee while the foot is fixed on the ground.[42]

Prevention

[edit]Interest in reducing non-contact ACL injury has been intense. The International Olympic Committee, after a comprehensive review of preventive strategies, has stated that injury prevention programs have a measurable effect on reducing injuries.[43] These programs are especially important in female athletes who bear higher incidence of ACL injury than male athletes, and also in children and adolescents who are at high risk for a second ACL tear.[44][45]

Researchers have found that female athletes often land with the knees relatively straight and collapsing inwards towards each other, with most of their bodyweight on a single foot and their upper body tilting to one side; these four factors put excessive strain on the ligaments on the knee and thus increase the likelihood of ACL tear.[46][18] There is evidence that engaging in neuromuscular training (NMT), which focus on hamstring strengthening, balance, and overall stability to reduce risk of injury by enhancing movement patterns during high risk movements. Such programs are beneficial for all athletes, particularly adolescent female athletes.[47][20]

Injury prevention programs (IPPs), are reliable in reducing the risk factors of ACL inquiries, referring to dominance theories. The ligament dominance theory reduced peak knee abduction moment but should be more focused on prioritizing individualized, task-specific exercises focusing on an athlete's risk profile.[48] It is more beneficial than a generic program. There is an increase in hip and knee flexion angles, such as plyometrics and jump-landing tasks, which reduces the risk of quadriceps dominance. However, there were no changes found for peak vGRF (vertical ground reaction force), which measures for "softer" landings. Unfortunately, there was no conclusive data on how IPPs reduces the risk associated with leg dominance theory.[48]

One effective strategy to lower ACL injury risk is to enhance tissue strength, thereby improving its ability to withstand greater loads. Studies have demonstrated that exercise can stimulate collagen regeneration in medial collateral ligamentous tissues of rabbits and ACL tissues of Rhesus monkeys, restoring them to 79% of healthy tissue strength after a period of immobilization. Surprisingly, there is a lack of published peer-reviewed studies showing that training can significantly increase strength in healthy ACL tissues through collagen regeneration. Moreover, research indicates that collagen concentration and ligament force tolerance in healthy ACL tissues decrease with age, highlighting the importance of reducing ACL loads. This can be achieved by adjusting athletes' technique during sports activities to lessen external joint loading or by enhancing the strength and activation of knee-supporting muscles when external joint loading is high.[49]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for ACL tears is important to:[50]

- Reduce abnormal knee movements and improve knee function

- Build trust and confidence to use the knee normally again

- Prevent further injury to the knee and reduce the risk of osteoarthritis

- Optimise long-term quality of life following the injury

Nonsurgical

[edit]Nonsurgical treatment for ACL rupture involves progressive, structured rehabilitation that aims to restore muscle strength, dynamic knee control and psychological confidence. A living systematic review with meta-analysis, updated in 2022, showed on the basis of three randomised controlled trials that primary rehabilitation with optional surgical reconstruction produces outcomes similar to early surgical reconstruction.[51] In some cases the ACL may heal without surgery during the rehabilitation process—the torn pieces re-unite to form a functional ligament.[52]

The purpose of exercise treatment is to restore the normal functioning of the muscular and balance system around the knee. Research has demonstrated that by training the muscles around the knee appropriately through exercise treatment, the body can 'learn' to control the knee again, and despite extra movement inside the knee, the knee can feel strong and able to withstand force.[citation needed]

Typically, this approach involves visiting a physical therapist or sports medicine professional soon after injury to oversee an intensive, structured program of exercises. Other treatments may be used initially, such as hands-on therapies in order to reduce pain. The physiotherapist will act as a coach through rehabilitation, usually by setting goals for recovery and giving feedback on progress.

Non-surgical recovery typically takes three to six months, and depends on the extent of the original injury, pre-existing fitness and commitment to the rehabilitation and sporting goals. Some patients may not be satisfied with the outcome of non-surgical management, and opt for surgery later.[citation needed]

Surgery

[edit]ACL reconstruction surgery involves replacing the torn ACL with a "graft," which is a tendon taken from another source. Grafts can be taken from the patellar tendon, hamstring tendon, quadriceps tendon from either the person undergoing the procedure ("autograft") or a cadaver ("allograft"). Of the three different kinds of autografts, quadriceps tendon grafts have shown to produce less pain at the site of the harvest when compared to patellar tendon and hamstring tendon grafts. Quadriceps tendon grafts have also been shown to produce better results when it comes to knee stability and function.[53]

The surgery is done with an arthroscope or tiny camera inserted inside the knee, with additional small incisions made around the knee to insert surgical instruments. This method is less invasive and is proven to result in less pain from surgery, less time in the hospital, and quicker recovery times than "open" surgery (in which a long incision is made down the front of the knee and the joint is opened and exposed).[1]

Young athletes or anyone opting for ACL surgery should consider delaying their surgery and completing a 4-6 week prehabilitation program. Although there is no consensus on what rehab should consist of, some of the basic parameters include restoring range of motion, decreasing swelling, and ensuring there is adequate quadriceps strength. Patients that received a 4-6 week prehab program had better outcomes in the acute phases of surgery, while the outcomes 3-6+months out are still inconclusive [54]

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons has stated that there is moderate evidence to support the guideline that ACL reconstruction should occur within five months of injury in order to improve a person's function and protect the knee from further injury; however, additional studies need to be done to determine the best time for surgery and to better understand the effect of timing on clinical outcomes.[55] However, delaying ACL reconstruction in pediatric and adolescent populations for more than 3 months has been shown to increase the risk or meniscus injuries significantly.[56]

There are over 100,000 ACL reconstruction surgeries per year in the United States. Over 95% of ACL reconstructions are performed in the outpatient setting. The most common procedures performed during ACL reconstruction are partial meniscectomy and chondroplasty.[57] Asymmetry in the repaired knee is a possibility and has been found to have a large effect between limbs for peak vertical ground reaction force, peak knee-extension moment, and loading rate during double-limb landings, as well as mean knee-extension moment and knee energy absorption during both double- and single-limb landings. Analysis of joint symmetry along with movement patterns should be a part of return to sports criteria.[58]

Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, and a question from the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score quality of life subscale. Results showed that nine athletes sustained a second ACL injury Athletes who experienced a second ACL injury had higher scores on the ACL-RSI and on the risk appraisal questions of the ACL-RSI, and they met RTS criteria sooner than athletes who did not sustain a second ACL injury. After reading, all second ACL injuries occurred in athletes who underwent primary ACL with hamstring tendon autografts.[59]

Rehabilitation

[edit]The goals of rehabilitation following an ACL injury are to regain knee strength and motion. If an individual with an ACL injury undergoes surgery, the rehabilitation process will first focus on slowly increasing the range of motion of the joint, then on strengthening the surrounding muscles to protect the new ligament and stabilize the knee. Finally, functional training specific to the activities required for certain sports is begun. Delaying return to sport is recommended for at least a minimum of nine months, as retear rates become 7x more likely for those returning prior to 9 months. Additionally, it takes around 2 years for the ACL to mature; however, it is unrealistic to expect athletes to wait two years to return to sports. Another factor to consider is that 30% of retear rates occur within the first 30 athletic exposures and 50% within the first 72 athletic exposures. Lastly, a patient reduces their likelihood of a retear with each month they delay return to sport after the 9 month mark.[60] In the pediatric setting, re-ruptures of the ACL post surgically are prevalent, 94.6% of which require a revision surgery. Without proper rehabilitation, growth or angular deformities can occur, also requiring a revision surgery.[61] Patients need to ensure their physical therapist is experienced with treating ACL patients as many therapists can set their patients up for failure. More than half of physical therapists still utilize manual muscle testing techniques to measure leg strength for return to sports which is subjective and not reliable data.[62] In addition, there is no agreed upon criteria for return to sport however there are considerations a therapist should make before clearing their patient. Patients should be put through battery of tests throughout their rehab to ensure their prepared for the demands of their sport. The tests should include a psychological component, plyometric testing, strength symmetry between both lower limbs, and different functional movement assessments that relate to the patients sport.[63]

There are numerous guidelines regarding ACL rehabilitation recommendations and interventions. A Guideline Development Group (GDG), composed of impartial clinical and methodology experts, was formed and tasked with converting evidence into recommendations. Each member graded proposed recommendations anonymously, and the evidence that produced a high-percentage agreement were published.[64]

Post-operative Strategies:

In 2022, a systematic review was conducted on ACL rehabilitation that refutes the usefulness of post-operative bracing. Despite its frequent use in common practive, bracing does not improve any functional outcomes and may in fact limit mobility unnecessarily. Emphasis should instead be placed on neuromuscular electrical stimulation, which has been shown to enhance muscle activation. Furthermore, it may reduce disuse atrophy, especially in the early recovery phase.[65]

Timing and structure of rehabilitation recommendations:

- Pre-operative rehabilitation is strongly recommended in order to improve post-operative quadriceps strength, knee range of motion and may decrease the time to return to sport. At least one pre-operative visit can be helpful to determine if there is sufficient voluntary muscle activation and to educate the patient on the post-operative rehabilitation route. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 96.1%)[64]

- Unsupervised exercise is recommended for patients recovering from ACL reconstructive surgery. Patients who have reduced access to physical therapy and/or have high motivation and are compliant to perform their rehabilitation are encouraged to exercise independently. Patients who are not well educated on body mechanics should have exercise programs individually prescribed and be monitored to ensure proper execution of rehabilitation protocol to prevent progression with adverse events. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 84.7%)[64]

- Duration of rehabilitation protocol is specific to an individual's needs and demonstration of their ability to safely return to preinjury level. Accelerated timelines can be used under the right conditions and without adverse events. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 97%)[64]

Modalities Recommendations:

- Continuous passive motion does not offer additional benefit for pain, range of motion, or swelling when compared to active motion exercises. It is recommended against using this modality because of this, as well as it being time-consuming and costly. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 75.5%)[64]

- Cryotherapy is inexpensive and easy to use. It also results in a high level of patient satisfaction and rarely has adverse events. The use of this modality is warranted in the early phase of postoperative management. Patients should be educated on how to safely apply cryotherapy to prevent injury. Compressive cryotherapy may be more effective, if available. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 97%)[64]

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is strongly recommended in the earliest phase after surgery. This modality will stimulate muscle activation while reducing the expected disuse muscle atrophy. In the early phase, NMES can be used during functional activities to further develop strength. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 93.4%)[64]

- A low-load blood flow restriction (BFR) is encouraged, along with standardized care, in the early phase of rehabilitation. This modality can improve quadriceps and hamstring strength, especially in individuals experiencing increased knee pain and/or cannot tolerate loads applied to the knee joint. Before a clinician decides to incorporate BFR, they should be aware of contraindications. Modal agreement: "strongly agree" (mean: 92.6%)[64]

- Dry Needling is not recommended for early rehabilitation phase, as it can increase risk of hemorrhage. Modal agreement "strongly agree" (mean: 67.6%)[64]

- Whole-body vibration is effective as an additional intervention to improve quadriceps strength and static balance. However, there have been reported complications of pain and swelling due to use of this intervention. It is recommended to refrain from using this modality due to the complications and high-cost. Modal agreement "agree" (mean: 83.2%)[64]

Return To Sport

Exercise interventions to help prevent secondary injury in return to sport. Exercise interventions consists of neuromuscular training, strength training, agility drills, and plyometrics. Exercises that are chosen are complementary of risk factors that could cause an ACL injury. Some plyometric and balance exercises that help the return to sport protocol include the triple hops, tuck jumps and box jumps, Nordic hamstrings and squats with hip abduction. Neuromuscular training is also very important in return to sport. Progressive perturbations on unstable surfaces that test unilateral and bilateral stance.[66]

A program of five phases of rehab was created to recover and return to sport post ACLR. Phase one consisted of ROM and mobility, diminish pain and swelling, and strengthen the quadriceps muscles. Phase two is jogging on the treadmill. Phase three started agility drills in different body planes, fast bursting movements. Phase 4 starts plyometrics, jumping with both feet. Finally phase five progresses the bilateral jumps to unilateral leg hops. In the later stages the rehabilitation program should be tailored towards the primary sport the athlete is trying to return to.[66]

In ACL-SPORTS programs an athlete must pass a predetermined return-to-sport test. The requirements are limb symmetry, there good sided leg strength is symmetrical to the ACLR side, of 90% in the quadriceps strength test, 90% in each of the four single-legged hop tests, 90% on the Knee Outcomes Survey-Activities of Daily Living scale (KOS-ADLs), and in general rating of self-perceived knee function. All athletes should achieve greater than 90% limb symmetry of good sided 1RM.[66]

Psychological readiness is a crucial factor in determining when an athlete can safely return to sport following ACL reconstruction. Research suggests that objective and subjective psychological assessments should be incorporated into rehabilitation protocols, as athletes with higher psychological readiness scores have lower re-injury rates (Glattke et al., 2022). Additionally, high-intensity plyometric training has been found to be ineffective in ACL recovery and may not contribute to improved functional outcomes (Glattke et al., 2022).[65]

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis of ACL injury is generally good, with many people regaining function of the injured leg within months.[2] ACL injury used to be a career-ending injury for competitive athletes; however, in recent years ACL reconstruction surgery followed by physical therapy has allowed many athletes to return to their pre-injury level of performance.[67]

Long term complications of ACL injury include early onset arthritis of the knee and/or re-tearing the ligament. Factors that increase risk of arthritis include severity of the initial injury, injury to other structures in the knee, and level of activity following treatment.[9] Not repairing tears to the ACL can sometimes cause damage to the cartilage inside the knee because with the torn ACL, the tibia and femur bone are more likely to rub against each other.[1] Nevertheless, ACL tears alone increase inflammatory markers in the knee which can have influence on the development of osteoarthritis.[68]

Young female athletes have a significant risk of re-tearing an ACL graft, or tearing the ACL on the other knee after their recovery. This risk has been recorded as being nearly 1 out of every 4 young athletes.[69] Therefore, athletes should be screened for any neuromuscular deficit (i.e. weakness greater in one leg than another, or incorrect landing form) before returning to sport.[17]

Epidemiology

[edit]There are around 200,000 ACL tears each year in the United States. ACL tears newly occur in about 69 per 100,000 per year with rates in males of 82 per 100,000 and females of 59 per 100,000.[70] When breaking down rates based on age and sex, females between the ages of 14 and 18 had the highest rates of injury with 227.6 per 100,000. Males between the ages of 19 and 24 had the highest rates of injury with 241 per 100,000.[70]

Sports

[edit]Rates of re-rupture among college athletes were highest in male football players with 15 per 10,000, followed by female gymnasts with 8 per 10,000 and female soccer players with 5.2 per 10,000.[71]

High school athletes are at increased risk for ACL tears when compared to non-athletes. Among high school girls in the US, the sport with the highest risk of ACL tear is soccer, followed by basketball and lacrosse. In the US women's basketball and soccer experience the most ACL tears then all other sports.[72] The highest risk sport for high school boys in the US was basketball, followed by lacrosse and soccer.[73] In basketball, women are 5-8 times more likely to experience an ACL tear than men.[72]

Dogs

[edit]Cruciate ligament rupture is a common orthopedic disorder in dogs. A study of insurance data showed the majority of the breeds with increased risk of cruciate ligament rupture were large or giant.[74]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries". OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons - AAOS. March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "ACL Injury: Does It Require Surgery?". OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD (March 2006). "Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 34 (3): 490–8. doi:10.1177/0363546505282619. PMID 16382007. S2CID 25395274.

- ^ a b Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Foss KD, Hewett TE (March 2015). "Specific exercise effects of preventive neuromuscular training intervention on anterior cruciate ligament injury risk reduction in young females: meta-analysis and subgroup analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 49 (5): 282–9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093461. PMID 25452612.

- ^ a b Prodromos CC, Han Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, Shi K (December 2007). "A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury-reduction regimen". Arthroscopy. 23 (12): 1320–1325.e6. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.003. PMID 18063176.

- ^ Montalvo AM, Schneider DK, Yut L, Webster KE, Beynnon B, Kocher MS, Myer GD (August 2019). "'What's my risk of sustaining an ACL injury while playing sports?' A systematic review with meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 53 (16): 1003–1012. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096274. PMC 6561829. PMID 29514822.

- ^ Williams, Sally (14 September 2024). "'Everyone says they hear a pop or a crack': why are so many female footballers suffering career-ending knee injuries?". The Guardian.

- ^ Monk AP, Davies LJ, Hopewell S, Harris K, Beard DJ, Price AJ (April 2016). "Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4) CD011166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011166.pub2. PMC 6464826. PMID 27039329.

- ^ a b c d "ACL injury - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 1 December 2022.

- ^ "7 Tips To Speed Up ACL Recovery - Elevate Rehabilitation". Elevate Rehabilitation and Performance. Retrieved 2025-05-27.

- ^ Dedinsky R, Baker L, Imbus S, Bowman M, Murray L (February 2017). "Exercises That Facilitate Optimal Hamstring and Quadriceps Co-Activation to Help Decrease Acl Injury Risk in Healthy Females: A Systematic Review of the Literature". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 12 (1): 3–15. PMC 5294945. PMID 28217412.

- ^ Silvers, Holly J. (2009-06-01). "Play at Your Own Risk: Sport, the Injury Epidemic, and ACL Injury Prevention in Female Athletes". Journal of Intercollegiate Sport. 2 (1): 81–98. doi:10.1123/jis.2.1.81. ISSN 1941-417X.

- ^ a b c Faryniarz DA, Bhargava M, Lajam C, Attia ET, Hannafin JA (2006). "Quantitation of estrogen receptors and relaxin binding in human anterior cruciate ligament fibroblasts". In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. Animal. 42 (7): 176–81. doi:10.1290/0512089.1. JSTOR 4295693. PMID 16948498. S2CID 2473817.

- ^ Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J (April–June 2007). "Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives". Journal of Athletic Training. 42 (2): 311–9. PMC 1941297. PMID 17710181.

- ^ Wojtys EM, Huston LJ, Schock HJ, Boylan JP, Ashton-Miller JA (May 2003). "Gender differences in muscular protection of the knee in torsion in size-matched athletes". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 85 (5): 782–9. doi:10.2106/00004623-200305000-00002. PMID 12728025. S2CID 42096840.

- ^ Samuelson K, Balk EM, Sevetson EL, Fleming BC (10 October 2017). "Limited Evidence Suggests a Protective Association Between Oral Contraceptive Pill Use and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Females: A Systematic Review". Sports Health. 9 (6): 498–510. doi:10.1177/1941738117734164. PMC 5665118. PMID 29016234.

- ^ a b Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, et al. (April 2005). "Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 33 (4): 492–501. doi:10.1177/0363546504269591. PMID 15722287. S2CID 31261104.

- ^ a b c d Hewett TE, Ford KR, Hoogenboom BJ, Myer GD (December 2010). "Understanding and preventing acl injuries: current biomechanical and epidemiologic considerations - update 2010". North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 5 (4): 234–51. PMC 3096145. PMID 21655382.

- ^ Pappas E, Carpes FP (January 2012). "Lower extremity kinematic asymmetry in male and female athletes performing jump-landing tasks". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 15 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.07.008. PMID 21925949.

- ^ a b Emery CA, Roy TO, Whittaker JL, Nettel-Aguirre A, van Mechelen W (July 2015). "Neuromuscular training injury prevention strategies in youth sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 49 (13): 865–70. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094639. PMID 26084526. S2CID 5953765.

- ^ Donnelly, Cyril J.; Jackson, Ben S.; Gucciardi, Daniel F.; Reinbolt, Jeff (January 2020). "Biomechanically-Informed Training: The Four Pillars for Knee and ACL Injury Prevention Built Upon Behavior Change and Motivation Principles". Applied Sciences. 10 (13): 4470. doi:10.3390/app10134470. ISSN 2076-3417.

- ^ "The female ACL: Why is it more prone to injury?". Journal of Orthopaedics. 13 (2): A1 – A4. March 2016. doi:10.1016/S0972-978X(16)00023-4. PMC 4805849. PMID 27053841.

- ^ Dragoo JL, Castillo TN, Braun HJ, Ridley BA, Kennedy AC, Golish SR (October 2011). "Prospective correlation between serum relaxin concentration and anterior cruciate ligament tears among elite collegiate female athletes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 39 (10): 2175–80. doi:10.1177/0363546511413378. PMID 21737831. S2CID 11088632.

- ^ Yu WD, Liu SH, Hatch JD, Panossian V, Finerman GA (September 1999). "Effect of estrogen on cellular metabolism of the human anterior cruciate ligament". Clin Orthop Relat Res. 366 (366): 229–238. doi:10.1097/00003086-199909000-00030. PMID 10627740.

- ^ "The Effect of Estrogen on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Structure and Function: A Systematic Review". clinmedjournals.org. Retrieved 2025-03-31.

- ^ DeFroda, Steven F.; Bokshan, Steven L.; Worobey, Samantha; Ready, Lauren; Daniels, Alan H.; Owens, Brett D. (November 2019). "Oral contraceptives provide protection against anterior cruciate ligament tears: a national database study of 165,748 female patients". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 47 (4): 416–420. doi:10.1080/00913847.2019.1600334. ISSN 2326-3660. PMID 30913940.

- ^ McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ (October 2005). "Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak knee valgus moment during sidestepping: implications for ACL injury". Clinical Biomechanics. 20 (8): 863–70. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.007. PMID 16005555.

- ^ Griffin L (2008). "Risk and Gender Factors for Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury". The anterior cruciate ligament: reconstruction and basic science. Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 18–27. ISBN 978-1-4160-3834-4.

- ^ Slauterbeck JR, Hickox JR, Beynnon B, Hardy DM (October 2006). "Anterior cruciate ligament biology and its relationship to injury forces". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 37 (4): 585–91. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.001. PMID 17141016.

- ^ Biondino CR (November 1999). "Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes". Connecticut Medicine. 63 (11): 657–60. PMID 10589146.

- ^ "Pivot Shift Test - Orthopedic Examination of the Knee". PHYSICAL THERAPY WEB. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ "Anterior Drawer Test - Orthopedic Examination of the Knee". PHYSICAL THERAPY WEB. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ "Lachman Test". Physiopedia. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GM (August 2013). "Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 21 (8): 1895–903. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2250-9. PMID 23085822. S2CID 25181956.

- ^ Gokeler, Alli; Seil, Romain; Kerkhoffs, Gino; Verhagen, Evert (2018-06-18). "A novel approach to enhance ACL injury prevention programs". Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics. 5 (1): 22. doi:10.1186/s40634-018-0137-5. ISSN 2197-1153. PMC 6005994. PMID 29916182.

- ^ MRI for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury at eMedicine

- ^ Atik OŞ, Çavuşoğlu AT, Ayanoğlu T (2015). "Is magnetic resonance imaging reliable for the evaluation of the ruptured or healed anterior cruciate ligament?". Joint Diseases & Related Surgery. 26 (1): 38–40. doi:10.5606/ehc.2015.09. PMID 25741919.

- ^ Stadnick, Michael (March 2006). "Partial ACL Tear". Radsource: PACS Radiology Systems.

- ^ Rohman EM, Macalena JA (June 2016). "Anterior cruciate ligament assessment using arthrometry and stress imaging". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 9 (2): 130–8. doi:10.1007/s12178-016-9331-1. PMC 4896874. PMID 26984335.

- ^ Robert H, Nouveau S, Gageot S, Gagnière B (May 2009). "A new knee arthrometer, the GNRB: experience in ACL complete and partial tears". Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 95 (3): 171–176. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2009.03.009. PMID 19423416.

- ^ Ryu SM, Na HD, Shon OJ (June 2018). "Diagnostic Tools for Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: GNRB, Lachman Test, and Telos". Knee Surgery & Related Research. 30 (2): 121–127. doi:10.5792/ksrr.17.014. PMC 5990229. PMID 29554717.

- ^ O'Donoghue DH (October 1950). "Surgical treatment of fresh injuries to the major ligaments of the knee". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 32 A (4): 721–38. doi:10.2106/00004623-195032040-00001. PMID 14784482.

- ^ Ardern CL, Ekås GR, Grindem H, Moksnes H, Anderson AF, Chotel F, et al. (April 2018). "2018 International Olympic Committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 52 (7): 422–438. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099060. PMC 5867447. PMID 29478021.

- ^ Lang PJ, Sugimoto D, Micheli LJ (June 2017). "Prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in children". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 8: 133–141. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S133940. PMC 5476725. PMID 28652828.

- ^ Dekker TJ, Godin JA, Dale KM, Garrett WE, Taylor DC, Riboh JC (June 2017). "Return to Sport After Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Its Effect on Subsequent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 99 (11): 897–904. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00758. PMID 28590374. S2CID 46577033.

- ^ Boden BP, Sheehan FT, Torg JS, Hewett TE (September 2010). "Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: mechanisms and risk factors". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 18 (9): 520–7. doi:10.5435/00124635-201009000-00003. PMC 3625971. PMID 20810933.

- ^ Myer GD, Sugimoto D, Thomas S, Hewett TE (January 2013). "The influence of age on the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 41 (1): 203–15. doi:10.1177/0363546512460637. PMC 4160039. PMID 23048042.

- ^ a b Lopes TJ, Simic M, Myer GD, Ford KR, Hewett TE, Pappas E (May 2018). "The Effects of Injury Prevention Programs on the Biomechanics of Landing Tasks: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (6): 1492–1499. doi:10.1177/0363546517716930. PMC 6604048. PMID 28759729.

- ^ Donnelly, C. J.; Elliott, B. C.; Ackland, T. R.; Doyle, T. L. A.; Beiser, T. F.; Finch, C. F.; Cochrane, J. L.; Dempsey, A. R.; Lloyd, D. G. (July 2012). "An Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Framework: Incorporating the Recent Evidence". Research in Sports Medicine. 20 (3–4): 239–262. doi:10.1080/15438627.2012.680989. ISSN 1543-8627. PMID 22742078.

- ^ Filbay SR, Grindem H (February 2019). "Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 33 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.018. PMC 6723618. PMID 31431274.

- ^ Saueressig T, Braun T, Steglich N, Diemer F, Zebisch J, Herbst M, et al. (November 2022). "Primary surgery versus primary rehabilitation for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a living systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 56 (21): 1241–1251. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-105359. PMC 9606531. PMID 36038357.

- ^ Ihara H, Kawano T (2017). "Influence of Age on Healing Capacity of Acute Tears of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 41 (2): 206–211. doi:10.1097/RCT.0000000000000515. PMC 5359784. PMID 28045756.

- ^ Mouarbes, Dany; Menetrey, Jacques; Marot, Vincent; Courtot, Louis; Berard, Emilie; Cavaignac, Etienne (December 2019). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Outcomes for Quadriceps Tendon Autograft Versus Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone and Hamstring-Tendon Autografts". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 47 (14): 3531–3540. doi:10.1177/0363546518825340. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 30790526. S2CID 73505146.

- ^ Cunha, Jamie; Solomon, Daniel J. (2022-01-01). "ACL Prehabilitation Improves Postoperative Strength and Motion and Return to Sport in Athletes". Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation. ASMAR Special Issue: Rehabilitation and Return to Sport in Athletes. 4 (1): e65 – e69. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2021.11.001. ISSN 2666-061X. PMC 8811524. PMID 35141537.

- ^ "Surgery Timing". OrthoGuidelines. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons - AAOS. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

When ACL reconstruction is indicated, moderate evidence supports reconstruction within five months of injury to protect the articular cartilage and menisci.

- ^ James, Evan W.; Dawkins, Brody J.; Schachne, Jonathan M.; Ganley, Theodore J.; Kocher, Mininder S.; PLUTO Study Group; Anderson, Christian N.; Busch, Michael T.; Chambers, Henry G.; Christino, Melissa A.; Cordasco, Frank A.; Edmonds, Eric W.; Green, Daniel W.; Heyworth, Benton E.; Lawrence, J. Todd R. (December 2021). "Early Operative Versus Delayed Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment of Pediatric and Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 49 (14): 4008–4017. doi:10.1177/0363546521990817. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 33720764. S2CID 232243480.

- ^ Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, Tanaka MJ, Cole BJ, Bach BR, Paletta GA (October 2014). "Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (10): 2363–2370. doi:10.1177/0363546514542796. PMID 25086064. S2CID 24764031.

- ^ Hughes G, Musco P, Caine S, Howe L (August 2020). "Lower Limb Asymmetry After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Adolescent Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Athletic Training. 55 (8): 811–825. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-0244-19. PMC 7462171. PMID 32607546.

- ^ Sigurðsson, Haraldur B.; Briem, Kristín; Silbernagel, Karin Grävare; Snyder-Mackler, Lynn (2022-08-01). "Don't Peak Too Early: Evidence for an ACL Injury Prevention Mechanism of the 11+ Program". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 17 (5): 823–831. doi:10.26603/001c.36524. PMC 9340830. PMID 35949375.

- ^ Brinlee, Alexander W.; Dickenson, Scott B.; Hunter-Giordano, Airelle; Snyder-Mackler, Lynn (2022). "ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation: Clinical Data, Biologic Healing, and Criterion-Based Milestones to Inform a Return-to-Sport Guideline". Sports Health. 14 (5): 770–779. doi:10.1177/19417381211056873. ISSN 1941-0921. PMC 9460090. PMID 34903114.

- ^ Wong, Stephanie E.; Feeley, Brian T.; Pandya, Nirav K. (September 2019). "Complications After Pediatric ACL Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 39 (8): e566 – e571. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000001075. ISSN 0271-6798. PMID 31393290. S2CID 199503697.

- ^ Gokeler, Alli; Dingenen, Bart; Hewett, Timothy E. (2022-01-01). "Rehabilitation and Return to Sport Testing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Where Are We in 2022?". Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation. ASMAR Special Issue: Rehabilitation and Return to Sport in Athletes. 4 (1): e77 – e82. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2021.10.025. ISSN 2666-061X. PMC 8811523. PMID 35141539.

- ^ Davies, George J.; McCarty, Eric; Provencher, Matthew; Manske, Robert C. (September 2017). "ACL Return to Sport Guidelines and Criteria". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 10 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1007/s12178-017-9420-9. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 5577421. PMID 28702921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kotsifaki, Roula; Korakakis, Vasileios; King, Enda; Barbosa, Olivia; Maree, Dustin; Pantouveris, Michail; Bjerregaard, Andreas; Luomajoki, Julius; Wilhelmsen, Jan; Whiteley, Rodney (March 2023). "Aspetar clinical practice guideline on rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 57 (9): 500–514. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106158. ISSN 1473-0480. PMC 11785408. PMID 36731908.

- ^ a b Glattke, Kaycee E.; Tummala, Sailesh V.; Chhabra, Anikar (2022-04-20). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Recovery and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 104 (8): 739–754. doi:10.2106/JBJS.21.00688. ISSN 1535-1386. PMID 34932514.

- ^ a b c Drole, Kristina; Paravlic, Armin H. (2022). "Interventions for increasing return to sport rates after an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: A systematic review". Frontiers in Psychology. 13 939209. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.939209. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 9443932. PMID 36072023.

- ^ Cohen PH (13 January 2021). Puffer JC, Yoon JR (eds.). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury". BMJ Best Practice. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ RODRIGUEZ-MERCHAN, E. Carlos; Encinas-Ullan, Carlos A. (January 2022). "Knee Osteoarthritis Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Frequency, Contributory Elements, and Recent Interventions to Modify the Route of Degeneration". The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 10 (11): 951–958. doi:10.22038/abjs.2021.52790.2616. PMC 9749126. PMID 36561222.

- ^ Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, Hewett TE (October 2010). "Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (10): 1968–78. doi:10.1177/0363546510376053. PMC 4920967. PMID 20702858.

- ^ a b Sanders TL, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan AJ, Larson DR, Dahm DL, Levy BA, et al. (June 2016). "Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (6): 1502–7. doi:10.1177/0363546516629944. PMID 26920430. S2CID 36050753.

- ^ Gans I, Retzky JS, Jones LC, Tanaka MJ (June 2018). "Epidemiology of Recurrent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association Sports: The Injury Surveillance Program, 2004-2014". Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 6 (6) 2325967118777823. doi:10.1177/2325967118777823. PMC 6024527. PMID 29977938.

- ^ a b Ireland ML, Gaudette M, Crook S (May 1997). "ACL Injuries in the Female Athlete". Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 6 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1123/jsr.6.2.97.

- ^ Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, Fabricant PD, Lawrence JT, Ganley TJ (October 2016). "Sport-Specific Yearly Risk and Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears in High School Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (10): 2716–2723. doi:10.1177/0363546515617742. PMID 26657853. S2CID 23050724.

- ^ Engdahl K, Emanuelson U, Höglund O, Bergström A, Hanson J (May 2021). "The epidemiology of cruciate ligament rupture in an insured Swedish dog population". Scientific Reports. 11 (1) 9546. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.9546E. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88876-3. PMC 8100293. PMID 33953264.