Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Abu Shusha

View on WikipediaAbu Shusha (Arabic: أبو شوشة) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, located 8 km southeast of Ramle. It was ethnically cleansed in May 1948.

Key Information

Abu Shusha was located on the slope of Tell Jezer/Tell el-Jazari, which is commonly identified with the ancient city of Gezer. In April–May 1948, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Abu Shusha was attacked several times. The final assault began on May 13, one day prior to Israel's declaration of independence. Abu Shusha residents attempted to defend the village, but the village was occupied on May 14. The civilians who had not already fled or been killed were expelled by May 21.[8] With their descendants, they numbered about 6,198 in 1998.

Name

[edit]Abu Shusheh is said to derive its name from a derwish who prayed for rain in a time of drought, and was told by a sand-diviner that he would perish if it came. The water came out of the earth (probably at Et Tannur) and formed a pool, into which he stepped and was drowned. The people, seeing only his topknot left, cried Ya Abu Shusheh (“Oh Father of the Topknot”).[2]

History

[edit]The Crusaders called the place Mont Gisart. In 1177 the Crusaders won a battle against Saladin there. Ceramics and coins from the 13th century have been found here.[7]

Ottoman era

[edit]

A Maqam (shrine) was built there possibly in the 16th century.[7] In 1838, Abu Shusheh was noted as a Muslim village in the Ibn Humar area in the District of Er-Ramleh.[9] Edward Robinson also noted the village on his travels in the region in 1852.[10]

In 1869 or 1872, the village lands were purchased by Melville Peter Bergheim of Jerusalem, a Protestant of German origin. Bergheim established a modern agricultural farm, using European methods and equipment. Bergheim's ownership of the land was hotly contested by the villagers, by legal and illegal means, including the murder of Bergheim's son Peter on 12 October 1885.[11] After the Bergheim company went bankrupt in 1892, Abu Shusa's lands were managed by a government receiver.[12]

In 1882, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) noted that the extent of land farmed by Mr. Bergheim at Abu Shusheh was 5,000 acres. The boundaries was shown on the Survey's map as a dotted line: ____ . . . . _____ . . . .[2] SWP further described Abu Shusha as a small village built of stone and adobe and surrounded by cactus hedges, populated by about 100 families.[13]

Elihu Grant, who visited the village, described it as "tiny" in 1907.[14] In 1910s, part of the land was sold by the government receiver to the villagers and the rest to the Jewish Colonization Association, which gave the villagers one third of their purchase in order to settle the dispute. After World War I, the land in Jewish hands was sold to the Maccabean Land Company, and later transferred to the Jewish National Fund.[12]

In November, 1917, the British 6th Mounted Brigade charged a Turkish detachment defending the heights above Abu Shusheh. The Turks suffered 'heavy casualties'.[15]

British Mandate era

[edit]In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Abu Shusheh had a population of 603 residents; all Muslims,[16] increasing in the 1931 census to 627, still all Muslims, in a total of 145 houses.[17]

The village had a mosque and a number of shops. A village school was founded in 1947, with an initial enrollment of 33 students.[7]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Abu Shusha was 870, all Muslims,[4] with a total land area of 9,425 dunams.[5] 2,475 dunums of village land were allotted to cereals, 54 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[18] while 24 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[19]

-

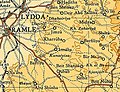

Abu Shusha 1942 1:20,000

-

Abu Shusha 1945 Scale 1:250,000

-

Abu Shusha 1945

-

Depopulated villages in the Ramle Subdistrict 9 July 1948

1948 massacre and aftermath

[edit]The village was attacked by the Givati Brigade on May 13–14, 1948 during Operation Barak. A few inhabitants fled but most remained. The Givati troops were immediately replaced by militia men from kibbutz Gezer, who were later replaced by troops from Kiryati Brigade.[20] On May 19, Arab Legion sources claimed that villagers were being killed. On May 21, Arab authorities appealed to the Red Cross to stop "barbaric acts" they said were being committed in Abu Shusha.[21] A Haganah soldier was reported to have twice attempted to rape a 20-year-old woman prisoner.[22] The residents that had remained in the village were expelled, apparently on 21 May.[21]

More recent research, including that conducted by Birzeit University, suggests that around 60 residents were massacred by the Givati Brigade during the attack.[23][24] In 1995 a mass grave with 52 skeletons was discovered, but their cause of death is undetermined.[25]

The Israeli settlement of Ameilim was founded nearby later in 1948, while Pedaya was established in 1951; both on village land.[7] The remains of the village were destroyed in 1965 as part of a government operation to clear the country of abandoned villages, which were regarded by the Israel Land Administration as "a blot on the landscape".[26]

In 1992 the village site was described: "The Israeli settlement of Ameilim occupies much of the site. Figs and cypress trees, cactuses and one palm tree grow on the site. The surrounding valleys are planted in apricots and figs, and various kinds of fruit trees are cultivated on the heights."[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 265

- ^ a b c Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 444

- ^ Karsh, Efraim. "How Many Palestinian Arab Refugees Were There?" Israel Affairs 17.2 (2011): 224-246. Academic Search Premier. Web. 29 May 2013.

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 29

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 66

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xix, village #246. Also gives cause of depopulation

- ^ a b c d e f g Khalidi, 1992, p. 358

- ^ Morris, 2004, pp. 256-257

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 120

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1856, pp. 143, 146

- ^ Peter Bergheim'sche Kriminalsache: Meuchelmond, JM-ISA/RG67/1-866/575-603/581, Israel State Archives

- ^ a b Ruth Kark, Changing patterns of landownership in nineteenth-century Palestine: the European influence, Journal of Historical Geography, vol 14, no 4 (1984) 357-384.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 407 Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 358

- ^ Grant, 1907, p. 17, quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 358

- ^ Bruce, 2002, p. 152

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 21

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 18

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 114

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 164

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 205

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. 257

- ^ "Doron" (Maoz) to HIS-AD, "The Interrogation of Women Prisoners in the village of Abu Shusha", 24 Jun. 1948, HA 105\92 aleph. Quoted in Morris, 2004, p. 257

- ^ "Abu Shusha - The Massacre". Birzeit University. Archived from the original on 2003-12-05. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ^ Ghanim, Honaida (2011). "The Nakba". In Rouhana, N. N.; Sabbagh-Khoury, A. (eds.). The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society (PDF). p. 23.

In the village of Abu Shusha in the District of Ramla a unit of the Givati Brigade committed a massacre in which 60 villagers were murdered.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Benvenisti, 1996, p. 248

- ^ Aron Shai, The fate of abandoned Arab villages in Israel, 1965-1969, History and Memory, Vol 18 (2006) pp86-106.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (1996). City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91868-9.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. On Demand Publishing. ISBN 1909609048.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Grant, E. (1907). The Peasantry of Palestine. Boston, New York [etc.]: The Pilgrim Press.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

External links

[edit]- Welcome to Abu-Shusha

- Abu Shusha (Ramla), Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 16: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Abu Shusha, from Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Abu Shusha by Rami Nashashibi (1996), Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society.

- Abu Shusha - A Survivor's Testimony by Rami Nashashibi (1996), Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society

Abu Shusha

View on GrokipediaAbu Shusha (Arabic: أبو شوشة) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, situated on the southern slope of Tall Jazar approximately 8 km southeast of Ramla.[1] The village, comprising around 145 stone and mud houses surrounded by cactus hedges, had a population of 870 Muslims according to 1945 British Mandate statistics, supported by a local economy focused on cereal cultivation across 9,425 dunums of land, much of which was owned or worked by Arabs despite significant Jewish land holdings in the area.[1] It included basic infrastructure such as a mosque, several shops, and an elementary school established in 1947 with 33 initial pupils.[1] During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Abu Shusha was targeted in Operation Barak, with the Haganah's Givati Brigade launching a mortar bombardment on 13 May followed by an assault that captured the village on 14 May, resulting in the deaths of approximately 70 Arab villagers amid combat and subsequent actions, while most residents fled or were displaced.[2][1] Israeli forces reported 30 Arab fatalities, but historian Benny Morris, drawing on archival evidence including Haganah records, documents a higher toll consistent with patterns of wartime massacres in the conflict.[2] The village was then systematically demolished, its lands repurposed for Israeli agricultural use and settlement, including the nearby moshav of Gezer established in 1945 and later expansions.[1] This event exemplifies the rapid depopulation of over 500 Palestinian localities during the war, driven by military operations amid mutual expulsions and atrocities on both sides, though Palestinian sources emphasize systematic expulsion while Israeli accounts frame it as defensive conquest.[2]

Name and Etymology

Origins and Variants

The name Abu Shusha (Arabic: أبو شوشة) derives linguistically from the Arabic "abū," meaning "father of," combined with "shūsha," referring to a tuft or topknot of hair, suggesting an eponymous designation for an ancestor or figure distinguished by such a feature.[3] This pattern of nomenclature, common in Arabic toponymy, reflects personal attributes rather than topographical or botanical elements, though no specific historical figure is definitively linked to the village's founding.[3] In Ottoman-era records and European surveys, the name appears with phonetic transliterations such as Abû Shûsheh or Abu Shusheh, as documented in 19th-century mappings of the region, reflecting inconsistencies in rendering Arabic script into Latin characters but preserving the core form.[4] British Mandate censuses standardized it as Abu Shusha. The Ramle subdistrict village must be differentiated from other Palestinian sites sharing the name, including Abu Shusha in the Haifa subdistrict (near Marj Ibn 'Amer) and Ghuwayr Abu Shusha in the Tiberias subdistrict (adjacent to the Sea of Galilee), each with analogous etymological roots but distinct locales and histories.[5][6]Geography and Environment

Location and Topography

Abu Shusha was situated in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, approximately 8.5 kilometers southeast of Ramla.[1] The village's coordinates are approximately 31°51′25″N 34°54′56″E. It lay at an average elevation of 200 meters above sea level.[1] The topography featured the southern slope of Tall Jazar, a prominent tell identified with the ancient site of Gezer, marking the juncture where the flat coastal plain transitions into the rising Jerusalem foothills.[1] This positioning on undulating ridges provided a mix of sloped terrain and proximity to broader plains conducive to settlement.[1] The village connected via a secondary road to the northeastward Jaffa-Jerusalem highway, facilitating access within the regional landscape.[1]Natural Resources and Agriculture

Abu Shusha's agricultural economy relied predominantly on rainfed cereal cultivation, reflecting the fertile soils of the coastal plain-foothills transition zone where the village was situated on the southern slope of Tell Jezer. In 1944/45, according to British Mandate Village Statistics, 2,475 dunums of the village's approximately 9,425 dunum land area were devoted to cereals such as wheat and barley, which formed the backbone of local farming due to the region's Mediterranean climate with adequate winter rainfall for dryland crops.[1][7] Limited irrigation supported smaller-scale orchard cultivation, with 54 dunums allocated for irrigated lands or fruit trees, enabling modest production amid the generally rain-dependent conditions.[4] The terrain's mix of valleys and heights facilitated diversified though primarily subsistence-based farming, with valleys planted in apricots and figs, while higher elevations hosted various fruit trees suited to the well-drained, loamy soils derived from the underlying limestone and alluvial deposits.[4] Grazing lands complemented crop production, utilizing uncultivated areas for livestock fodder, though olive groves were not prominent based on recorded land use patterns. This structure underscored a mixed farming system adapted to the area's moderate topography and seasonal water availability from wadis rather than abundant perennial springs.[8]Demographics and Economy

Population Trends

In the late Ottoman period, surveys such as the Survey of Western Palestine (1870s–1880s) described Abu Shusha as a modest village populated by approximately 100 families, implying a resident population of around 500–600 individuals, primarily engaged in subsistence agriculture.[1] The British Mandate's first census in 1922 recorded a population of 603, all Muslims, reflecting stability in a rural Arab community structured around extended family clans (hamulas).[9] By the 1931 census, this had increased modestly to 627 Muslims, indicating gradual natural growth amid limited external migration.[9] [10] Official Village Statistics compiled in April 1945 reported further expansion to 870–1,130 residents, all Muslims, driven by improved health conditions and proximity to urban centers like Ramla and Lydda, which attracted some seasonal labor migration for employment opportunities while maintaining the village's core agrarian base.[11] [12] The demographic composition remained uniformly Muslim Arab throughout, with social organization centered on clan networks and a minor elite of local mukhtars overseeing communal affairs.[1]Economic Activities and Land Ownership

The economy of Abu Shusha prior to 1948 was predominantly agrarian, with residents relying on the cultivation of cereal crops such as wheat and barley on approximately 2,475 dunums of Arab-owned land dedicated to such uses. A smaller portion, 54 dunums, was allocated to plantations and irrigable areas, supporting limited orchard production. Animal husbandry supplemented agricultural activities, though specific herd sizes are undocumented for the village. Some villagers sought supplementary income through wage labor at the adjacent Gezer (Tall al-Jazar) archaeological excavations, where men earned 5 piasters per day, while women and boys received 2.5 piasters, reflecting gendered pay disparities in early 20th-century digs.[13] [1] Land ownership in 1945 encompassed 9,425 dunums total, with Arabs holding 2,896 dunums (about 31%), Jewish owners controlling 6,337 dunums (67%), and public lands accounting for 192 dunums (2%). This distribution indicates that while local Arabs maintained smallholder cultivation on their portions, substantial Jewish-owned tracts—likely managed as estates or leased—may have provided additional employment or rental opportunities, though direct evidence of widespread leasing in Abu Shusha is limited. The village included a few shops for basic commerce, facilitating trade of surplus produce toward the nearby Ramla market, the district center. Waqf endowments and communal holdings existed in the broader region but are not quantified specifically for Abu Shusha, with absentee ownership appearing minimal among Arab lands.[1]| Land Category (1945) | Arab (dunums) | Jewish (dunums) | Public (dunums) | Total (dunums) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | 2,896 | 6,337 | 192 | 9,425 |

| Land Use (1945) | Arab (dunums) | Jewish (dunums) | Total (dunums) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 2,475 | 5,569 | 8,044 |

| Plantations/Irrigable | 54 | 0 | 54 |

| Non-Cultivable | 343 | 768 | 1,303 |

| Built-up | 24 | 0 | 24 |

Historical Overview

Ottoman Period

Abu Shusha developed as a small agricultural settlement during the late Ottoman period, likely in the 19th century, within the nahiya of Ramla in the Sanjak of Jerusalem.[1] No records of earlier settlement appear in Ottoman archives, though artifacts such as Ottoman-era ceramics and coins have been found at the site, suggesting possible intermittent use prior to formal village establishment. The village functioned primarily as an outpost for farming, with residents cultivating grains and other crops under the empire's land tenure system. Administrative records from the period highlight the village's integration into Ottoman fiscal structures, including the miri tax on arable land and produce, which supported modest economic activity centered on agriculture.[14] In the 1870s, Abu Shusha residents faced significant back tax obligations totaling 46,000 piasters, involving transactions by 51 peasants representing around 400 individuals to settle debts with local authorities.[15] This episode reflects typical Ottoman practices of tax farming and periodic revenue assessments in rural Palestine, where villages like Abu Shusha contributed through cash and kind payments derived from harvests. The village maintained stability under regional Ottoman governance, with limited documented conflicts, as local mukhtars managed internal affairs and reported to Ramla officials amid the broader imperial administration of the area.[16] Surveys such as the Palestine Exploration Fund's mapping efforts in the 1870s recorded the site's topography and proximity to ancient tells, underscoring its role in the continuity of settled agriculture in the region without major disruptions during this era.[17]British Mandate Period

During the British Mandate for Palestine (1920–1948), Abu Shusha was administratively classified within the Ramle sub-district, part of the broader Jaffa district initially, reflecting the reorganization of administrative units following the Ottoman era. The village's population, predominantly Muslim, was recorded in official censuses as growing modestly amid regional demographic shifts. The 1922 Census of Palestine enumerated 603 inhabitants, all Muslims, while the 1931 census reported 627 residents. By the 1945 Village Statistics compiled by the Mandate government, the population had increased to 870 Muslims, indicating steady but limited expansion consistent with rural Arab communities in the area.[9][11] Land ownership in Abu Shusha underwent notable changes during this period, with significant portions transferred to Jewish entities through legal sales. The 1945 Village Statistics documented a total land area of 9,425 dunums, of which 6,337 dunums (approximately 67%) were held by Jewish owners, primarily through organizations like the Jewish National Fund, while 2,896 dunums remained Arab-owned and 192 dunums public. These acquisitions often stemmed from pre-Mandate purchases, such as lands sold to the Maccabean Land Company after World War I and subsequently managed by Jewish agencies, which heightened local awareness of economic pressures but did not precipitate major recorded disturbances in the village before 1936.[11] Infrastructure developments under British administration improved connectivity for the village, situated along routes linking Ramle to the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem axis. Proximity to the coastal plain facilitated agricultural transport, though the village itself remained agrarian with no major urban projects documented specifically for Abu Shusha. These enhancements supported economic activities but also underscored growing socio-economic disparities amid land transactions, contributing to underlying tensions in the Ramle region without village-specific violent incidents prior to the mid-1930s Arab Revolt.[11]The 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Strategic Context and Pre-War Hostilities

The UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 on November 29, 1947, recommending the partition of Mandatory Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, with economic union and international administration for Jerusalem.[18] Arab leadership, including the Palestine Arab Higher Committee, immediately rejected the plan, viewing it as unjust given the demographic and land ownership realities, and called for strikes and protests that escalated into organized violence against Jewish communities and infrastructure.[19] This rejection triggered the 1947–1948 civil war phase, characterized by Arab-initiated riots, ambushes, and blockades targeting Jewish economic and transport links, particularly the vital Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road corridor through the Ramle subdistrict.[19] Abu Shusha, situated on the southern slope of Tell Jazar approximately 8 kilometers southeast of Ramle, occupied a tactically advantageous position at the junction of the coastal plain and Jerusalem foothills, overlooking secondary roads and wadis used for movement between Arab-controlled towns like Ramle and inland villages.[1] Following the partition vote, local Arab irregulars and village militias in the Ramle area, including from nearby towns, participated in attacks on Jewish bus and truck convoys transiting the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem route, with documented ambushes at Ramle on December 4, 1947, rendering sections of the road nearly impassable despite armored escorts.[20] These actions formed part of a broader Arab strategy to sever Jewish supply lines to Jerusalem, where shortages of food and arms quickly intensified; reports indicate Arab bands from Ramle and surrounding villages exploited elevated terrain like Tell Jazar for sniping and hit-and-run raids on passing traffic.[19] In response, Jewish defense forces such as the Haganah organized local guards and conducted retaliatory operations against Arab positions deemed threats to the road. By early 1948, villages in the Ramle subdistrict, including Abu Shusha, hosted National Guard units—irregular militias armed and coordinated by the Arab Higher Committee—used as staging points for cross-road attacks.[19] On April 1, 1948, Haganah's Givati Brigade raided Abu Shusha in an operation explicitly described by its planners as a "studied retaliatory" measure, targeting fighters reportedly based there after prior convoy assaults; two platoons destroyed houses and inflicted casualties before withdrawing, reflecting the tit-for-tat skirmishes that defined the pre-invasion hostilities.[7] Such engagements underscored the village's role in the escalating cycle of Arab blockades and Jewish countermeasures aimed at securing transit corridors.[19]Military Operations Leading to Capture

Operation Barak, launched by the Haganah's Givati Brigade on May 9, 1948, aimed to capture and clear Arab villages along the southern coastal plain and western approaches to the interior, securing Jewish-held territories in anticipation of the British Mandate's expiration on May 15 and the expected Egyptian military incursion from the south.[21] The operation's planning emphasized rapid advances from Tel Aviv southward to preempt Arab consolidation of positions that could sever supply lines to isolated Jewish settlements in the Negev and disrupt mobilization efforts ahead of Israel's declaration of independence.[21] Givati units, recently expanded with new recruits and volunteers, were tasked with methodically targeting villages identified through intelligence as hosting irregular fighters who had participated in ambushes on Jewish convoys and patrols.[22] Preceding the main assaults, Givati conducted reconnaissance patrols and preparatory artillery barrages on key sites, including Abu Shusha, to suppress defenses and confirm enemy dispositions amid heightened Arab irregular activity that threatened the brigade's operational zone.[23] These actions were informed by Haganah intelligence reports detailing local Palestinian militias' coordination with broader Arab efforts, including support from the Arab Liberation Army's irregulars, to interdict Jewish movements along the Ramle-Latrun axis.[23] The brigade's 51st and 57th Battalions, bolstered by mortar and machine-gun support, positioned for envelopment maneuvers designed to exploit terrain advantages, such as the low hills around Abu Shusha that provided observation points for Arab snipers.[21] This localized push aligned with the Haganah's strategic imperative to consolidate the southern front against multifaceted threats from local forces and invading armies, ensuring territorial continuity for the nascent state during the impending truce mediated by the United Nations.[21] Operations like Barak represented a shift toward proactive clearance of hostile enclaves, drawing on lessons from earlier engagements such as the defense against ALA probes in central Palestine, to mitigate vulnerabilities exposed by fragmented Arab command structures.[23]Events of May 13-14, 1948

On the evening of May 13, 1948, during Operation Barak, units of the Haganah's Givati Brigade initiated an attack on Abu Shusha with mortar bombardment to soften defenses.[1] This artillery fire targeted the village's positions, preparing the ground for a subsequent infantry assault launched from the south and east.[1] The assault encountered resistance from local villagers and members of the Arab National Guard, who defended stoutly against the advancing forces.[1] Hand-to-hand combat ensued in several areas as the attackers pushed into the village.[1] By the morning of May 14, the Givati Brigade had overrun and captured the village.[1] In the immediate aftermath, the remaining inhabitants who had not fled were expelled from the site.[24] The village's structures were then systematically demolished using explosives to render the location uninhabitable and prevent potential reoccupation or use as a base by enemy forces.[24]Controversies Surrounding the 1948 Events

Accounts of Violence and Casualties

Palestinian oral histories and contemporary Arab reports assert that 60-70 villagers, including women and children, were killed by forces of the Givati Brigade during the capture of Abu Shusha on May 13-14, 1948, with allegations of executions, rape, and indiscriminate violence against non-combatants following the village's surrender.[4][25] A report relayed to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) at the time described "barbaric acts" by Jewish forces, including the killing of 70 civilians and instances of sexual assault.[25] In contrast, operational records from the Givati Brigade indicated around 30 Arab fatalities, primarily attributed to combat during the assault and shelling, while disputing claims of deliberate targeting of civilians after the fighting ceased; one Israeli soldier was reported killed in the action.[1] Historian Benny Morris, drawing on declassified Israeli archives, estimates the death toll at approximately 70, acknowledging post-battle killings but framing them within the context of wartime expulsions rather than a premeditated massacre.[26] These accounts diverge significantly on the scale and nature of civilian involvement in the casualties. In 1995, a mass grave containing 52 skeletons was unearthed near the former village site, providing physical evidence of deaths but without determination of causes, as no forensic analysis occurred immediately after the events due to the intensity of the ongoing war.[27] The lack of prompt independent investigations amid active hostilities has hindered definitive corroboration of either side's figures.Differing Narratives and Viewpoints

Palestinian narratives frame the capture of Abu Shusha on May 14, 1948, as an unprovoked massacre constituting ethnic cleansing, with Zionist forces under the Givati Brigade shelling the village and executing unarmed villagers, including women and children, to instill terror and facilitate the expulsion of Arab populations from strategic areas.[7] These accounts, drawn from survivor testimonies and Palestinian historical compilations, emphasize the premeditated nature of the assault during Operation Barak, portraying it as part of a broader pattern of village destruction aimed at preventing return and securing Jewish territorial control, independent of military necessity.[28] Israeli narratives, as articulated by military historians and participants, depict the operation against Abu Shusha as a essential wartime measure to neutralize a fortified Arab base that had repeatedly launched attacks on Jewish convoys along the vital Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road, thereby threatening supply lines during the civil war phase preceding Israel's independence declaration.[26] Proponents of this view, including analyses of Haganah records, equate the action to defensive clearances comparable to Arab forces' massacre of 127 Jewish civilians and fighters at Kfar Etzion in May 1948, arguing that the village's hostile role—serving as a staging point for irregulars—necessitated its reduction to avert encirclement and ensure Jewish survival amid pan-Arab invasion threats.[28] Both perspectives incorporate the influence of Arab Higher Committee directives, though interpreted divergently: Israeli accounts cite early 1948 broadcasts and statements urging jihad and temporary evacuation to clear paths for invading armies as precipitating factors in village abandonments, including pre-assault flights from Abu Shusha environs, while Palestinian viewpoints attribute such claims to post-hoc rationalizations minimizing expulsions' role.[29] Neutral observers, referencing declassified documents, note the Committee's inconsistent messaging—initial panic-inducing rhetoric followed by May appeals to halt flights—but stress these as secondary to direct military pressures in Abu Shusha's case.[28]Scholarly Assessments and Verifiable Evidence

Historians such as Benny Morris, drawing on declassified Israeli military archives and contemporaneous reports, have documented the expulsion of Abu Shusha's remaining inhabitants following its capture by the Givati Brigade on May 14, 1948, during Operation Barak, amid the broader chaos of the Arab-Israeli War's total conflict dynamics.[26] Morris notes shelling preceded the assault, leading to flight by most villagers, with those not evacuating facing expulsion orders, but emphasizes this as reactive wartime clearance rather than premeditated extermination policy.[1] Claims of a deliberate massacre killing 60-70 civilians, primarily from Palestinian oral histories collected post-1948, lack corroboration in Israeli operational logs, which record combat deaths and isolated atrocities like the rape of four female detainees but no systematic slaughter of non-combatants.[2] Empirical verification remains constrained: no mass graves or forensic traces have been archaeologically confirmed at the site, contrasting with sites like Deir Yassin where physical evidence aligned with higher casualty figures from cross-verified accounts.[26] Morris cross-references Haganah and IDF documents indicating 20-30 Arab fighters killed in resistance, with civilian losses inflated in refugee narratives possibly due to conflation with nearby engagements or wartime rumor amplification, a pattern observed across 1948 expulsions where testimonial discrepancies exceed archival data.[2] Scholarly critiques, including Morris's revisions, attribute such divergences to the fog of mutual existential threats—Jewish forces post-Holocaust facing Arab armies' explicit annihilation pledges—yielding reciprocal expulsions and reprisals without evidence of genocidal intent in Abu Shusha's case.[26] Comparative historiography underscores symmetry in atrocities: while Abu Shusha saw limited verified excesses amid expulsion, Arab irregulars executed hundreds in the Etzion Bloc massacres days earlier (May 1948), including mutilations documented in survivor and Red Cross reports, framing both as fear-driven escalations in a war where survival imperatives overrode restraint.[26] This evidence-based lens prioritizes causal chains of preemptive operations against villages hosting hostile fighters over ideologically laden narratives of unilateral ethnic cleansing, with Morris arguing expulsions averted Jewish annihilation amid invading armies' advances.[2] Absent material artifacts or neutral observer records (e.g., UN truce teams arrived post-event), assessments hinge on archival primacy, revealing a microcosm of 1948's decentralized violence rather than orchestrated pogroms.[26]Post-War Developments

Establishment of Israeli Settlements

In the immediate aftermath of the 1948 war, the Israeli settlement of Ameilim was established on the site of the former village of Abu Shusha to create a security buffer along strategic routes and to initiate agricultural cultivation in the depopulated area.[1] This move aligned with broader efforts to consolidate control over captured territories and resettle Jewish immigrants or veterans in frontier zones vulnerable to infiltration.[4] By 1951, the moshav Pedaya was founded on adjacent lands previously held by Abu Shusha residents, targeting immigrants primarily from Iraq to foster mixed farming and rural self-sufficiency.[30] The moshav's establishment reflected state policies to absorb mass immigration—over 700,000 Jews arrived between 1948 and 1951—by reallocating underutilized lands for productive use.[7] These reallocations operated under the Absentees' Property Law of December 1950, which vested in the state custodian properties of individuals deemed "absentees" due to flight or displacement during the war, enabling their transfer to Jewish settlements for security, demographic strengthening, and economic development without compensation to original owners.[31] The law applied retroactively from May 1948, facilitating rapid repopulation of some 400 abandoned Arab villages, including Abu Shusha, as part of Israel's foundational land policies.[32]Archaeological and Modern Land Use

The archaeological site associated with Abu Shusha is the adjacent Tell Jezer, identified as the ancient city of Gezer, which has yielded evidence of continuous occupation from the Chalcolithic period through the Iron Age and into Hellenistic and Roman times.[33] Excavations began in the late 19th century with surveys by the Palestine Exploration Fund, followed by major digs led by R.A.S. Macalister between 1902 and 1909, which uncovered Bronze Age fortifications, Iron Age structures, and a high place potentially linked to Canaanite cultic practices.[34] Prior to 1948, these efforts, including later work in the 1930s, frequently employed laborers from the Abu Shusha village located on the tell's slopes, reflecting local involvement in uncovering pre-Islamic layers such as Middle Bronze Age gates and Late Bronze Age destruction levels attributed to Egyptian campaigns.[35] Post-1948 archaeological investigations at Gezer continued under Israeli auspices, with significant projects by the Hebrew Union College and Harvard University from 1964 to 1974 revealing stratified Philistine and Israelite pottery sequences, and subsequent excavations by the University of Arizona in the 1980s and 1990s exposing Solomonic-era gates and water systems.[36] Ongoing work by the Tandy Institutes for Archaeology has focused on radiocarbon dating and Iron Age chronology, confirming low chronology alignments for monumental structures without altering core understandings of the site's multi-layered history.[37] The tell itself was designated a national park in the late 20th century, preserving visible remains like the six-chambered gates while allowing limited salvage and research digs.[38] The lands of the former Abu Shusha village have been repurposed for agriculture by nearby Israeli settlements, including cultivation of figs, cypresses, orchards, and cacti, marking a shift from pre-1948 cereal and fruit farming to afforested and irrigated plots integrated into regional infrastructure.[7] No major archaeological interventions have occurred directly at the village site itself, with the area supporting routine farming activities adjacent to the preserved Gezer tell; the site's incorporation into modern Israeli road networks and agricultural zones reflects post-war land reallocations without documented recent transformative developments beyond maintenance of existing uses.[38]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Abu_Shusha_%281870s%29.jpg

.jpg/250px-Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Abu_Shusha_(1870s).jpg)

.jpg)