Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alligator

View on Wikipedia

| Alligators Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

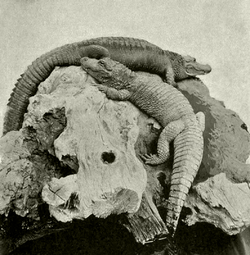

| 1905 photograph of an American alligator (top) and a Chinese alligator (bottom) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Subfamily: | Alligatorinae |

| Genus: | Alligator Cuvier, 1807 |

| Type species | |

| Alligator mississippiensis Daudin, 1802

| |

| Species | |

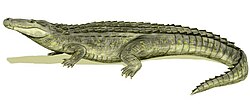

An alligator, or colloquially gator, is a large reptile in the genus Alligator of the family Alligatoridae in the order Crocodilia. The two extant species are the American alligator (A. mississippiensis) and the Chinese alligator (A. sinensis). Additionally, several extinct species of alligator are known from fossil remains. Alligators first appeared during the late Eocene epoch about 37 million years ago.[1]

The term "alligator" is likely an anglicized form of el lagarto, Spanish for "the lizard", which early Spanish explorers and settlers in Florida called the alligator.[2] Early English spellings of the name included allagarta and alagarto.[3]

Alligators are notable for their ability to inhabit climates that are considerably more temperate than those of most other crocodilians. Although they generally prefer subtropical to tropical regions, they are also capable of surviving colder winters in the northern parts of their range.[4]

Evolution

[edit]Alligators and caimans split in North America during the early Tertiary or late Cretaceous (about 53 million to 65 million years ago).[5][6] The Chinese alligator split from the American alligator about 33 million years ago[5] and probably descended from a lineage that crossed the Bering land bridge during the Neogene. The modern American alligator is well represented in the fossil record of the Pleistocene.[7] The alligator's full mitochondrial genome was sequenced in the 1990s.[8] The full genome, published in 2014, suggests that the alligator evolved much more slowly than mammals and birds.[9]

Phylogeny

[edit]The genus Alligator belongs to the subfamily Alligatorinae, which is the sister taxon to Caimaninae (the caimans). Together, these two subfamilies form the family Alligatoridae. The cladogram below shows the phylogeny of alligators.[10][11]

| Alligatoridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species

[edit]Extant

[edit]| Image | Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alligator mississippiensis | American alligator | the Southeastern United States |

|

Alligator sinensis | Chinese alligator | eastern China |

Extinct

[edit]Description

[edit]

An average adult American alligator's weight and length is 360 kg (790 lb) and 4 m (13 ft), but they sometimes grow to 4.4 m (14 ft) long and weigh over 450 kg (990 lb).[12] The largest ever recorded, found in Louisiana, measured 5.84 m (19.2 ft).[13] The Chinese alligator is smaller, rarely exceeding 2.1 m (7 ft) in length. Additionally, it weighs considerably less, with males rarely over 45 kg (100 lb).

Adult alligators are black or dark olive-brown with white undersides, while juveniles have bright yellow or whitish stripes which sharply contrast against their dark hides, providing them additional camouflage amongst reeds and wetland grasses.[14]

Alligators commonly live up to 50 years, but there have been examples of alligators living over 70.[15] One of the oldest recorded alligator lives was that of Saturn, an American alligator who was hatched in 1936 in Mississippi and spent nearly a decade in Germany before spending the majority of his life at the Moscow Zoo, where he died at the age of 83 or 84 on 22 May 2020.[16][17] Another one of the oldest lives on record is that of Muja, an American alligator who was brought as an adult specimen to the Belgrade Zoo in Serbia from Germany in 1937. Although no valid records exist about his date of birth, as of 2012, he was in his 80s and possibly the oldest alligator living in captivity.[18][19]

Habitat

[edit]Alligators are native only to the United States and China.[20][21]

American alligators are found in the southeast United States: all of Florida and Louisiana; the southern parts of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi; coastal South and North Carolina; East Texas, the southeast corner of Oklahoma, and the southern tip of Arkansas. Louisiana has the largest alligator population.[22] The majority of American alligators inhabit Florida and Louisiana, with over a million alligators in each state. Southern Florida is the only place where both alligators and crocodiles coexist.[23][24]

American alligators live in freshwater environments, such as ponds, marshes, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and swamps, as well as in brackish water.[25] When they construct alligator holes in the wetlands, they increase plant diversity and provide habitat for other animals during droughts.[26] They are, therefore, considered an important species for maintaining ecological diversity in wetlands.[27] Farther west, in Louisiana, heavy grazing by nutrias and muskrats is causing severe damage to coastal wetlands. Large alligators feed extensively on nutrias, and provide a vital ecological service by reducing nutria numbers.[28]

The Chinese alligator currently is found in only the Yangtze River valley and parts of adjacent provinces[21] and is extremely endangered, with only a few dozen believed to be left in the wild. Far more Chinese alligators live in zoos around the world than can be found in the wild. Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge in southern Louisiana has several in captivity in an attempt to preserve the species. Miami MetroZoo in Florida also has a breeding pair of Chinese alligators.

Behavior

[edit]

Large male alligators are solitary territorial animals. Smaller alligators can often be found in large numbers close to each other. The largest of the species (both males and females) defend prime territory; smaller alligators have a higher tolerance for other alligators within a similar size class.

Alligators move on land by two forms of locomotion, referred to as "sprawl" and "high walk". The sprawl is a forward movement with the belly making contact with the ground and is used to transition to "high walk" or to slither over wet substrate into water. The high walk is an up-on-four-limbs forward motion used for overland travel with the belly well up from the ground.[29] Alligators have also been observed to rise up and balance on their hind legs and semi-step forward as part of a forward or upward lunge. However, they can not walk on their hind legs.[30][31][32]

Although the alligator has a heavy body and a slow metabolism, it is capable of short bursts of speed, especially in very short lunges. Alligators' main prey are smaller animals they can kill and eat with a single bite. They may kill larger prey by grabbing it and dragging it into the water to drown. Alligators consume food that cannot be eaten in one bite by allowing it to rot or by biting and then performing a "death roll", spinning or convulsing wildly until bite-sized chunks are torn off. Critical to the alligator's ability to initiate a death roll, the tail must flex to a significant angle relative to its body. An alligator with an immobilized tail cannot perform a death roll.[33]

Most of the muscle in an alligator's jaw evolved to bite and grip prey. The muscles that close the jaws are powerful, but the muscles for opening their jaws are weak. As a result, an adult human can hold an alligator's jaws shut bare-handed. It is common to use several wraps of duct tape to prevent an adult alligator from opening its jaws when being handled or transported.[34]

Alligators are generally timid towards humans and tend to walk or swim away if one approaches. This may encourage people to approach alligators and their nests, which can provoke the animals into attacking. In Florida, feeding wild alligators at any time is illegal. If fed, the alligators will eventually lose their fear of humans and will learn to associate humans with food.[35]

Diet

[edit]

The type of food eaten by alligators depends upon their age and size. When they are young, alligators eat fish, insects, snails, crustaceans, and worms. As they mature, progressively larger prey is taken, including larger fish, such as gar, turtles, and various mammals, particularly nutrias and muskrats,[25] as well as birds, deer, and other reptiles.[36][37] Their stomachs also often contain gizzard stones. They will even consume carrion if they are sufficiently hungry. In some cases, larger alligators are known to ambush dogs, Florida panthers, and black bears, making them the apex predator throughout their distribution. In this role as a top predator, it may determine the abundance of prey species, including turtles and nutrias.[38][28] As humans encroach into their habitat, attacks are few but not unknown. Alligators, unlike the large crocodiles, do not immediately regard a human upon encounter as prey, but may still attack in self-defense if provoked.

Reproduction

[edit]Alligators generally mature at a length of 1.8 m (6 ft). The mating season is in late spring. In April and May, alligators form so-called "bellowing choruses". Large groups of animals bellow together for a few minutes a few times a day, usually one to three hours after sunrise. The bellows of male American alligators are accompanied by powerful blasts of infrasound.[39] Another form of male display is a loud head-slap.[40] In 2010, on spring nights alligators were found to gather in large numbers for group courtship, the so-called "alligator dances".[41]

In summer, the female builds a nest of vegetation where the decomposition of the vegetation provides the heat needed to incubate the eggs. The sex of the offspring is determined by the temperature in the nest and is fixed within seven to 21 days of the start of incubation. Incubation temperatures of 30 °C (86 °F) or lower produce a clutch of females; those of 34 °C (93 °F) or higher produce entirely males. Nests constructed on leaves are hotter than those constructed on wet marsh, so the former tend to produce males and the latter, females. The baby alligator's egg tooth helps it get out of its egg during hatching time. The natural sex ratio at hatching is five females to one male. Females hatched from eggs incubated at 30 °C (86 °F) weigh significantly more than males hatched from eggs incubated at 34 °C (93 °F).[42] The mother defends the nest from predators and assists the hatchlings to water. She will provide protection to the young for about a year if they remain in the area. Adult alligators regularly cannibalize younger individuals, though estimates of the rate of cannibalism vary widely.[43][44] In the past, immediately following the outlawing of alligator hunting, populations rebounded quickly due to the suppressed number of adults preying upon juveniles, increasing survival among the young alligators.[citation needed]

Anatomy

[edit]

Alligators, much like birds, have been shown to exhibit unidirectional movement of air through their lungs.[45] Most other amniotes are believed to exhibit bidirectional, or tidal breathing. For a tidal breathing animal, such as a mammal, air flows into and out of the lungs through branching bronchi which terminate in small dead-end chambers called alveoli. As the alveoli represent dead-ends to flow, the inspired air must move back out the same way it came in. In contrast, air in alligator lungs makes a circuit, moving in only one direction through the parabronchi. The air first enters the outer branch, moves through the parabronchi, and exits the lung through the inner branch. Oxygen exchange takes place in extensive vasculature around the parabronchi.[46]

The alligator has a similar digestive system to that of the crocodile, with minor differences in morphology and enzyme activity.[47] Alligators have a two-part stomach, with the first smaller portion containing gastroliths. It is believed this portion of the stomach serves a similar function as it does in the gizzard of some species of birds, to aid in digestion. The gastroliths work to grind up the meal as alligators will take large bites or swallow smaller prey whole. This process makes digestion and nutrient absorption easier once the food reaches the second portion of the stomach.[48] Once an alligator's meal has been processed it will move on to the second portion of the stomach which is highly acidic. The acidity of the stomach has been observed to increase once digestion begins. This is due to the increase in CO2 concentration of the blood, resulting from the right to left shunting of the alligators heart. The right to left shunt of the heart in alligators means the circulatory system will recirculate blood through the body instead of back to the lungs.[49] The re-circulation of blood leads to higher CO2 concentration as well as lower oxygen affinity.[50] There is evidence to suggest that there is increased blood flow diverted to the stomach during digestion to facilitate an increase in CO2 concentration which aids in increasing gastric acid secretions during digestion.[51][49] The alligator's metabolism will also increase after a meal by up to four times its basal metabolic rate.[52] Alligators also have highly folded mucosa in the lining of the intestines to further aid in the absorption of nutrients. The folds result in greater surface area for the nutrients to be absorbed through.[53]

Alligators also have complex microbiomes that are not fully understood yet, but can be attributed to both benefits and costs to the animal. These microorganisms can be found in the high surface area of the mucosa folds of the intestines, as well as throughout the digestive tract. Benefits include better total health and stronger immune system. However alligators are still vulnerable to microbial infections despite the immune boost from other microbiota.[53]

During brumation the process of digestion experiences changes due to the fasting most alligators experience during these periods of inactivity. Alligators that go long enough without a meal during brumation will begin a process called autophagy, where the animal begins to consume its fat reserves to maintain its body weight until it can acquire a sufficient meal.[54] There is also fluctuation in the level of bacterial taxa populations in the alligator's microbial community between seasons which helps the alligator cope with different rates of feeding and activity.[55]

Like other crocodilians, alligators have an armor of bony scutes. The dermal bones are highly vascularised and aid in calcium balance, both to neutralize acids while the animal cannot breathe underwater[56] and to provide calcium for eggshell formation.[57]

Alligators have muscular, flat tails that propel them while swimming.

The two kinds of white alligators are albino and leucistic. These alligators are practically impossible to find in the wild. They could survive only in captivity and are few in number.[58][59] The Aquarium of the Americas in New Orleans has leucistic alligators found in a Louisiana swamp in 1987.[59]

Human uses

[edit]

Alligators are raised commercially for their meat and their skin, which when tanned is used for the manufacture of luggage, handbags, shoes, belts, and other leather items. Alligators also provide economic benefits through the ecotourism industry. Visitors may take swamp tours, in which alligators are a feature. Their most important economic benefit to humans may be the control of nutrias and muskrats.[28]

Alligator meat is also consumed by humans.[60][61]

Differences from crocodiles

[edit]While there are rules of thumb for distinguishing alligators from crocodiles, all of them admit exceptions. Such general rules include:

- Exposed vs. interdigitated teeth: The easiest way to distinguish crocodiles from alligators is by looking at their jaw line. The teeth on the lower jaw of an alligator fit into sockets in the upper jaw, leaving only the upper teeth visible when the mouth is closed. The teeth on the lower jaw of a crocodile fit into grooves on the outside of the top jaw, making both the upper and lower teeth visible when the mouth is closed, thus creating a "toothy grin".[62]

- Shape of the nose and jaw: Alligators have wider, shovel-like, U-shaped snouts, while crocodile snouts are typically more pointed or V-shaped. The alligators' broader snouts have been contentiously thought to allow their jaws to withstand the stress of cracking open the shells of turtles and other hard-shelled animals that are widespread in their environments.[62][63][page needed] A 2012 study found very little correlation between bite force and snout shape amongst 23 tested crocodilian species.[64]

- Functioning salt glands: Crocodilians have modified salivary glands called salt glands on their tongues, but while these organs still excrete salt in crocodiles and gharials, those in most alligators and caimans have lost this ability, or excrete it in only extremely small quantities.[62] The ability to excrete excess salt allows crocodiles to better tolerate life in saline water and migrating through it.[62] Because alligators and caimans have lost this ability, they are largely restricted to freshwater habitats, although larger alligators do sometimes live in tidal mangroves and in very rare cases in coastal areas.[62]

- Integumentary sense organs: Both crocodiles and alligators have small, pit-like sensory organs called integumentary sense organs (ISOs) or dermal pressure receptors (DPRs) surrounding their upper and lower jaws.[62] These organs allow crocodilians to detect minor pressure changes in surrounding water, and assist them in locating and capturing prey. In crocodiles, however, such organs extend over nearly the entire body.[62] Crocodile ISOs may also assist in detection of local salinity, or serve other chemosensory functions.[62]

- Less consistent differences: Crocodiles are generally thought of as more aggressive than alligators.[62] Of the 26 crocodilian species,[65] only six are considered dangerous to adult human beings, most notably the Nile crocodile and saltwater crocodile. Each year, hundreds of deadly attacks are attributed to the Nile crocodile in sub-Saharan Africa. The American crocodile is considered to be less aggressive. Only a few (unverified) cases of American crocodiles fatally attacking humans have been reported.[66]

Image gallery of extant species

[edit]-

Alligator in the Everglades National Park

-

Alligator in the Canberra Zoo in Australia

-

Gator in Louisiana bayou swims

-

Gator in Louisiana bayou eats

-

Juvenile alligator found in Everglades National Park

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ. 9 e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMC 8428266. PMID 34567843.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionaries (2007). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries: English Words That Come From Spanish. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-618-91054-0.

- ^ Morgan, G. S., Richard, F., & Crombie, R. I. (1993). The Cuban crocodile, Crocodylus rhombifer, from late quaternary fossil deposits on Grand Cayman. Caribbean Journal of Science, 29(3–4), 153–164. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "North Carolina Alligator Management Plan North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission October 5, 2017 With July 12, 2018 Addendum". ncwildlife.gov.

- ^ a b Pan, T.; Miao, J.-S.; Zhang, H.-B.; Yan, P.; Lee, P.-S.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Ouyang, J.-H.; Deng, Y.-P.; Zhang, B.-W.; Wu, X.-B. (2020). "Near-complete phylogeny of extant Crocodylia (Reptilia) using mitogenome-based data". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191 (4): 1075–1089. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa074.

- ^ Oaks, J.R. (2011). "A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of the true crocodiles". Evolution. 65 (11): 3285–3297. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01373.x. PMID 22023592. S2CID 7254442.

- ^ Brochu, C.A. (1999). "Phylogenetics, taxonomy, and historical biogeography of Alligatoroidea". Memoir (Society of Vertebrate Paleontology). 6: 9–100. doi:10.2307/3889340. JSTOR 3889340.

- ^ Janke, A.; Arnason, U. (1997). "The complete mitochondrial genome of Alligator mississippiensis and the separation between recent archosauria (birds and crocodiles)". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (12): 1266–72. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025736. PMID 9402737.

- ^ Green RE, Braun EL, Armstrong J, Earl D, Nguyen N, Hickey G, Vandewege MW, St John JA, Capella-Gutiérrez S, Castoe TA, Kern C, Fujita MK, Opazo JC, Jurka J, Kojima KK, Caballero J, Hubley RM, Smit AF, Platt RN, Lavoie CA, Ramakodi MP, Finger JW, Suh A, Isberg SR, Miles L, Chong AY, Jaratlerdsiri W, Gongora J, Moran C, Iriarte A, McCormack J, Burgess SC, Edwards SV, Lyons E, Williams C, Breen M, Howard JT, Gresham CR, Peterson DG, Schmitz J, Pollock DD, Haussler D, Triplett EW, Zhang G, Irie N, Jarvis ED, Brochu CA, Schmidt CJ, McCarthy FM, Faircloth BC, Hoffmann FG, Glenn TC, Gabaldón T, Paten B, Ray DA (2014). "Three crocodilian genomes reveal ancestral patterns of evolution among archosaurs". Science. 346 (6215) 1254449. doi:10.1126/science.1254449. PMC 4386873. PMID 25504731.

- ^ Hastings, A. K.; Bloch, J. I.; Jaramillo, C. A.; Rincon, A. F.; MacFadden, B. J. (2013). "Systematics and biogeography of crocodylians from the Miocene of Panama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (2): 239. Bibcode:2013JVPal..33..239H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.713814. S2CID 83972694.

- ^ Brochu, C. A. (2011). "Phylogenetic relationships of Necrosuchus ionensis Simpson, 1937 and the early history of caimanines". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 163: S228 – S256. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00716.x.

- ^ "American Alligator and our National Parks". eparks.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ "Alligator mississippiensis". alligatorfur.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ "Crocodilian Species – American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)". crocodilian.com.

- ^ Wilkinson, Philip M.; Rainwater, Thomas R.; Woodward, Allan R.; Leone, Erin H.; Carter, Cameron (November 2016). "Determinate Growth and Reproductive Lifespan in the American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis): Evidence from Long-term Recaptures". Copeia. 104 (4): 843–852. doi:10.1643/CH-16-430.

- ^ "Berlin WW2 bombing survivor Saturn the alligator dies in Moscow Zoo". BBC News. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Hitler's Alligator - The Last German Prisoner of War in Russia. Mark Felton Productions. 2020-07-16. Archived from the original on 2021-06-14. Retrieved 2021-09-07 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Oldest alligator in the world". b92.net. 9 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ "Muja the alligator still alive and snapping in his 80s at Belgrade Zoo". Reuters. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Elsey, R.; Woodward, A.; Balaguera-Reina, S.A. (2019). "Alligator mississippiensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019 e.T46583A3009637. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T46583A3009637.en.

- ^ a b Jiang, H.; Wu, X. (2018). "Alligator sinensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T867A3146005. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T867A3146005.en.

- ^ 2005 Scholastic Book of World Records

- ^ "Trappers catch crocodile in Lake Tarpon", Tampa Bay Times, July 12, 2013

- ^ "Species Profile: American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) – SREL Herpetology". uga.edu. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ a b Dundee, H. A., and D. A. Rossman. 1989. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- ^ Craighead, F. C., Sr. (1968). The role of the alligator in shaping plant communities and maintaining wildlife in the southern Everglades. The Florida Naturalist, 41, 2–7, 69–74.

- ^ Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Chapter 4.

- ^ a b c Keddy PA, Gough L, Nyman JA, McFalls T, Carter J, Siegnist J (2009). "Alligator hunters, pelt traders, and runaway consumption of Gulf coast marshes: a trophic cascade perspective on coastal wetland losses". pp. 115–133. In: Silliman BR, Grosholz ED, Bertness MD (editors) (2009). Human Impacts on Salt Marshes: A Global Perspective. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- ^ Reilly & Elias, Locomotion In Alligator Mississippiensis: Kinematic Effects Of Speed And Posture and Their Relevance To The Sprawling-to-Erect Paradigm The Journal of Experimental Biology 201, 2559–2574 (1998)

- ^ Alligator Leap. Zooguy2. 2007-09-20. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2021-09-07 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Answers to Some Nagging Questions". The Washington Post. 2008-01-17. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ Alligator Attacks White Ibis Chick & Jumps Vertically at Pinckney Island. Karen Marts. 2014-08-17. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-09-07 – via YouTube.

- ^ Fish, Frank E.; Bostic, Sandra A.; Nicastro, Anthony J.; Beneski, John T. (2007). "Death roll of the alligator: mechanics of twist feeding in water". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (16): 2811–2818. doi:10.1242/jeb.004267. PMID 17690228. S2CID 8402869.

- ^ "Crocodilian Captive Care FAQ (Caiman, Alligator, Crocodile)". crocodilian.com. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ "Living with Alligators". Archived from the original on 2010-11-26. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Wolfe, J. L., D. K. Bradshaw, and R. H. Chabreck. 1987. Alligator feeding habits: New data and a review. Northeast Gulf Science 9: 1–8.

- ^ Gabrey, S. W. 2005. Impacts of the coypu removal program on the diet of American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) in south Louisiana. Report to Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, New Orleans.

- ^ Bondavalli, C., and R. E. Ulanowicz. 1998. Unexpected effects of predators upon their prey: The case of the American alligator. Ecosystems 2: 49–63.

- ^ "Can Animals Predict Disaster? – Listening to Infrasound | Nature". PBS. 2004-12-26. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

- ^ Garrick, L. D.; Lang, J. W. (1977). "Social Displays of the American Alligator". American Zoologist. 17: 225–239. doi:10.1093/icb/17.1.225.

- ^ Dinets, V. (2010). "Nocturnal behavior of the American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) in the wild during the mating season" (PDF). Herpetological Bulletin. 111: 4–11.

- ^ Mark W. J. Ferguson; Ted Joanen (1982). "Temperature of egg incubation determines sex in Alligator mississippiensis". Nature. 296 (5860): 850–853. Bibcode:1982Natur.296..850F. doi:10.1038/296850a0. PMID 7070524. S2CID 4307265.

- ^ Rootes, William L.; Chabreck, Robert H. (30 September 1993). "Cannibalism in the American Alligator". Herpetologica. 49 (1): 99–107. JSTOR 3892690.

- ^ Delany, Michael F; Woodward, Allan R; Kiltie, Richard A; Moore, Clinton T (20 May 2011). "Mortality of American Alligators Attributed to Cannibalism". Herpetologica. 67 (2): 174–185. doi:10.1655/herpetologica-d-10-00040.1. S2CID 85198798.

- ^ Farmer, C. G.; Sanders, K. (January 2010). "Unidirectional Airflow in the Lungs of Alligators". Science. 327 (5963): 338–340. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..338F. doi:10.1126/science.1180219. PMID 20075253. S2CID 206522844.

- ^ Science News; February 13, 2010; Page 11

- ^ Tracy, Christopher R.; McWhorter, Todd J.; Gienger, C. M.; Starck, J. Matthias; Medley, Peter; Manolis, S. Charlie; Webb, Grahame J. W.; Christian, Keith A. (2015-12-01). "Alligators and Crocodiles Have High Paracellular Absorption of Nutrients, But Differ in Digestive Morphology and Physiology". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 55 (6): 986–1004. doi:10.1093/icb/icv060. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 26060211.

- ^ Romão, Mariluce Ferreira; Santos, André Luiz Quagliatto; Lima, Fabiano Campos; De Simone, Simone Salgueiro; Silva, Juliana Macedo Magnino; Hirano, Líria Queiroz; Vieira, Lucélia Gonçalves; Pinto, José Guilherme Souza (March 2011). "Anatomical and Topographical Description of the Digestive System of Caiman crocodilus (Linnaeus 1758), Melanosuchus niger (Spix 1825) and Paleosuchus palpebrosus (Cuvier 1807)". International Journal of Morphology. 29 (1): 94–99. doi:10.4067/s0717-95022011000100016. ISSN 0717-9502.

- ^ a b Malte, Christian Lind; Malte, Hans; Reinholdt, Lærke Rønlev; Findsen, Anders; Hicks, James W.; Wang, Tobias (2017-02-15). "Right-to-left shunt has modest effects on CO 2 delivery to the gut during digestion, but compromises oxygen delivery". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 220 (4): 531–536. doi:10.1242/jeb.149625. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 27980124. S2CID 760441.

- ^ Busk, M.; Overgaard, J.; Hicks, J. W.; Bennett, A. F.; Wang, T. (October 2000). "Effects of feeding on arterial blood gases in the American alligator Alligator mississippiensis". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 20): 3117–3124. doi:10.1242/jeb.203.20.3117. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 11003822.

- ^ Findsen, Anders; Crossley, Dane A.; Wang, Tobias (2018-01-01). "Feeding alters blood flow patterns in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 215: 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.09.001. ISSN 1095-6433. PMID 28958765.

- ^ Kay, Jarren C.; Elsey, Ruth M.; Secor, Stephen M. (2020-05-01). "Modest Regulation of Digestive Performance Is Maintained through Early Ontogeny for the American Alligator, Alligator mississippiensis". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 93 (4): 320–338. doi:10.1086/709443. ISSN 1522-2152. PMID 32492358. S2CID 219057993.

- ^ a b Keenan, S. W.; Elsey, R. M. (2015-04-17). "The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown: Microbial Symbioses of the American Alligator". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 55 (6): 972–985. doi:10.1093/icb/icv006. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 25888944.

- ^ Hale, Amber; Merchant, Mark; White, Mary (May 2020). "Detection and analysis of autophagy in the American alligator ( Alligator mississippiensis )". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 334 (3): 192–207. Bibcode:2020JEZB..334..192H. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22936. ISSN 1552-5007. PMID 32061056. S2CID 211122872.

- ^ Tang, Ke-Yi; Wang, Zhen-Wei; Wan, Qiu-Hong; Fang, Sheng-Guo (2019). "Metagenomics Reveals Seasonal Functional Adaptation of the Gut Microbiome to Host Feeding and Fasting in the Chinese Alligator". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 2409. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02409. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 6824212. PMID 31708889.

- ^ Wednesday, 25 April 2012 Anna SallehABC (2012-04-25). "Antacid armour key to tetrapod survival". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dacke, C.; Elsey, R.; Trosclair, P.; Sugiyama, T.; Nevarez, Javier; Schweitzer, Mary (2015-09-01). "Alligator osteoderms as a source of labile calcium for eggshell formation". Journal of Zoology. 297 (4): 255–264. doi:10.1111/jzo.12272.

- ^ Anitei, Stefan. "White albino alligators". Softpedia. softpedia.com. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ^ a b "Mississippi River Gallery".

- ^ International Food Information Service (2009). IFIS Dictionary of Food Science and Technology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4051-8740-4.

- ^ Martin, Roy E.; Carter, Emily Paine; Flick, George J. Jr.; Davis, Lynn M. (2000). Marine and Freshwater Products Handbook. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-56676-889-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Britton, Adam. "FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: What's the difference between a crocodile and an alligator?". Crocodilian Biology Database. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Grigg, Gordon; Kirshner, David (2015). Biology and Evolution of Crocodylians. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4863-0066-2.

- ^ Erickson, G. M.; Gignac, P. M.; Steppan, S. J.; Lappin, A. K.; Vliet, K. A.; Brueggen, J. A.; Inouye, B. D.; Kledzik, D.; Webb, G. J. W. (2012). Claessens, Leon (ed.). "Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation". PLOS ONE. 7 (3) e31781. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731781E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031781. PMC 3303775. PMID 22431965.

- ^ "Conservation Status". Crocodile Specialist Group. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Pinou, Theodora. "American Crocodile: Species Description". Yale EEB Herpetology Web Page. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

External links

[edit]- Crocodilian Online Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Photo exhibit on alligators in Florida; made available by the State Archives of Florida

- Interview with a Seminole alligator wrestler; made available for public use by the State Archives of Florida

Alligator

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Phylogeny

Classification

The genus Alligator belongs to the family Alligatoridae, within the order Crocodylia, class Reptilia, phylum Chordata, and kingdom Animalia.[2][6] The term "alligator" derives from the Spanish phrase el lagarto, meaning "the lizard," coined by 16th-century Spanish explorers upon encountering the reptiles in Florida and other parts of the Americas.[7] The family Alligatoridae encompasses alligators and caimans, distinguishing it from the Crocodylidae family, which includes true crocodiles; Alligatoridae contains eight extant species across multiple genera, while Crocodylidae has 16 species.[6][8] Phylogenetically, the genus Alligator represents one of the primary lineages within Alligatoridae, characterized by synapomorphies such as a broad, U-shaped snout and upper jaw that contrasts with the narrower, V-shaped morphology of crocodylids.[8]Evolutionary History

The genus Alligator first appeared during the late Eocene epoch, approximately 37 million years ago, near the Eocene-Oligocene boundary, with early fossils documented from north-central North America.[9][10] This origin coincides with a period of global cooling following the warmer Eocene climates, marking the initial diversification of the Alligatorinae subfamily within the broader Alligatoridae family. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that Alligatorinae diverged from Caimaninae around 53–65 million years ago in North America, during the early Paleogene, establishing the foundational split within alligatorids.[11] Key evolutionary adaptations in Alligator species include the development of traits suited to ambush predation, such as a broad, U-shaped snout optimized for crushing hard-shelled prey like turtles, and powerful jaw muscles that enable sudden, energy-efficient strikes from concealment.[12][13] Compared to other crocodilians, alligators evolved greater tolerance for cooler climates, facilitated by behaviors like brumation (a form of reptilian hibernation) and physiological adjustments that allow survival in temperate regions without the need for constant high temperatures.[14] These adaptations likely contributed to their persistence amid fluctuating Paleogene environments. The Miocene epoch (23–5.3 million years ago) saw a significant radiation of Alligator species across North America and into Eurasia, driven by warm, humid conditions during the mid-Miocene climatic optimum that expanded suitable wetland habitats.[15] However, diversity declined sharply in the Pliocene (5.3–2.6 million years ago) due to progressive global cooling and aridification, which reduced tropical ranges and led to extinctions of many lineages.[15] Alligators survived the Quaternary ice ages (2.6 million years ago to present) by retreating to southern refugia in North America and Asia, where milder conditions preserved viable populations, demonstrating their resilience to repeated glacial-interglacial cycles.[16] A 2023 discovery in Thailand identified Alligator munensis, an extinct species from the Quaternary period approximately 230,000 years ago, based on a near-complete skull unearthed in 2005 from Nakhon Ratchasima Province.[16][17] This finding underscores early Asian dispersal of alligators, predating their dominance in North America and providing evidence for transcontinental migrations before modern distributions solidified.[18] A simplified cladogram of early alligatorid phylogeny illustrates the divergence:- Alligatoroidea (Late Cretaceous origin)

- Caimaninae (diverged ~53–65 mya)

- Alligatorinae

- Early forms (late Eocene, ~37 mya)

- Alligator genus (Oligocene–present)

- Extinct species (e.g., A. munensis, Quaternary)

- Extant species (e.g., A. mississippiensis, A. sinensis)