Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aniline

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Aniline[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Benzenamine | |||

| Other names

Phenylamine

Aminobenzene Benzamine | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 605631 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.491 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 2796 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1547 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H5NH2 | |||

| Molar mass | 93.129 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 1.0297 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | −6.30 °C (20.66 °F; 266.85 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 184.13 °C (363.43 °F; 457.28 K) | ||

| 3.6 g/(100 mL) at 20 °C | |||

| Vapor pressure | 0.6 mmHg (20 °C)[2] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) |

| ||

| −62.95·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.58364 | ||

| Viscosity | 3.71 cP (3.71 mPa·s at 25 °C) | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−3394 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

potential occupational carcinogen | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H311, H317, H318, H331, H341, H351, H372, H400 | |||

| P201, P202, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P273, P280, P281, P301+P310, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P311, P312, P314, P321, P322, P330, P333+P313, P361, P363, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 70 °C (158 °F; 343 K) | ||

| 770 °C (1,420 °F; 1,040 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.3–11%[2] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LDLo (lowest published)

|

195 mg/kg (dog, oral) 250 mg/kg (rat, oral) 464 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 440 mg/kg (rat, oral) 400 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral)[4] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

175 ppm (mouse, 7 h)[4] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

250 ppm (rat, 4 h) 180 ppm (cat, 8 h)[4] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 5 ppm (19 mg/m3) [skin][2] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca [potential occupational carcinogen][2] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

100 ppm[2] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related aromatic amines

|

1-Naphthylamine 2-Naphthylamine | ||

Related compounds

|

Phenylhydrazine Nitrosobenzene Nitrobenzene | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Aniline (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

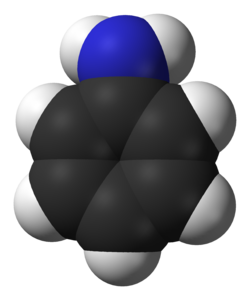

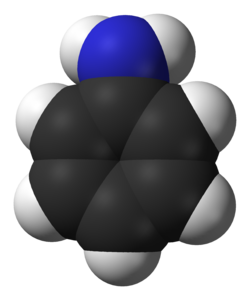

Aniline (From Portuguese: anil, meaning 'indigo shrub', and -ine indicating a derived substance)[6] is an organic compound with the formula C6H5NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group (−C6H5) attached to an amino group (−NH2), aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starting material for fine chemical synthesis. Its main use is in the manufacture of precursors to polyurethane, dyes, and other industrial chemicals. Like most volatile amines, it has the odor of rotten fish. It ignites readily, burning with a smoky flame characteristic of aromatic compounds.[7] It is toxic to humans.

Relative to benzene, aniline is "electron-rich". It thus participates more rapidly in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. Likewise, it is also prone to oxidation: while freshly purified aniline is an almost colorless oil, exposure to air results in gradual darkening to yellow or red, due to the formation of strongly colored, oxidized impurities. Aniline can be diazotized to give a diazonium salt, which can then undergo various nucleophilic substitution reactions.

Like other amines, aniline is both a base (pKaH = 4.6) and a nucleophile, although less so than structurally similar aliphatic amines.

Because an early source of the benzene from which they are derived was coal tar, aniline dyes are also called coal tar dyes.

Structure

[edit]

Aryl-N distances

[edit]In aniline, the C−N bond length is 1.41 Å,[8] compared to the C−N bond length of 1.47 Å for cyclohexylamine,[9] indicating partial π-bonding between C(aryl) and N.[10] The length of the chemical bond of C(aryl)−NH2 in anilines is highly sensitive to substituent effects. The C−N bond length is 1.34 Å in 2,4,6-trinitroaniline vs 1.44 Å in 3-methylaniline.[11]

Pyramidalization

[edit]The amine group in anilines is a slightly pyramidalized molecule, with hybridization of the nitrogen somewhere between sp3 and sp2. The nitrogen is described as having high p character. The amino group in aniline is flatter (i.e., it is a "shallower pyramid") than that in an aliphatic amine, owing to conjugation of the lone pair with the aryl substituent. The observed geometry reflects a compromise between two competing factors: 1) stabilization of the N lone pair in an orbital with significant s character favors pyramidalization (orbitals with s character are lower in energy), while 2) delocalization of the N lone pair into the aryl ring favors planarity (a lone pair in a pure p orbital gives the best overlap with the orbitals of the benzene ring π system).[12][13]

Consistent with these factors, substituted anilines with electron donating groups are more pyramidalized, while those with electron withdrawing groups are more planar. In the parent aniline, the lone pair is approximately 12% s character, corresponding to sp7.3 hybridization.[12][clarification needed] (For comparison, alkylamines generally have lone pairs in orbitals that are close to sp3.)

The pyramidalization angle between the C–N bond and the bisector of the H–N–H angle is 142.5°.[14] For comparison, in more strongly pyramidal amine group in methylamine, this value is ~125°, while that of the amine group in formamide has an angle of 180°.

Production

[edit]Industrial aniline production involves hydrogenation of nitrobenzene (typically at 200–300 °C) in the presence of metal catalysts:[15] Approximately 4 billion kilograms are produced annually. Catalysts include nickel, copper, palladium, and platinum,[7] and newer catalysts continue to be discovered.[16]

The reduction of nitrobenzene to aniline was first performed by Nikolay Zinin in 1842, using sulfide salts (Zinin reaction). The reduction of nitrobenzene to aniline was also performed as part of reductions by Antoine Béchamp in 1854, using iron as the reductant (Bechamp reduction). These stoichiometric routes remain useful for specialty anilines.[17]

Aniline can alternatively be prepared from ammonia and phenol derived from the cumene process.[7]

In commerce, three brands of aniline are distinguished: aniline oil for blue, which is pure aniline; aniline oil for red, a mixture of equimolecular quantities of aniline and ortho- and para-toluidines; and aniline oil for safranine, which contains aniline and ortho-toluidine and is obtained from the distillate (échappés) of the fuchsine fusion.[18]

Related aniline derivatives

[edit]Many analogues and derivatives of aniline are known where the phenyl group is further substituted. These include toluidines, xylidines, chloroanilines, aminobenzoic acids, nitroanilines, and many others. They also are usually prepared by nitration of the substituted aromatic compounds followed by reduction. For example, this approach is used to convert toluene into toluidines and chlorobenzene into 4-chloroaniline.[7] Alternatively, using Buchwald-Hartwig coupling or Ullmann reaction approaches, aryl halides can be aminated with aqueous or gaseous ammonia.[19]

Reactions

[edit]The chemistry of aniline is rich because the compound has been cheaply available for many years. Below are some classes of its reactions.

Oxidation

[edit]

The oxidation of aniline has been heavily investigated, and can result in reactions localized at nitrogen or more commonly results in the formation of new C-N bonds. In alkaline solution, azobenzene results, whereas arsenic acid produces the violet-coloring matter violaniline. Chromic acid converts it into quinone, whereas chlorates, in the presence of certain metallic salts (especially of vanadium), give aniline black. Hydrochloric acid and potassium chlorate give chloranil. Potassium permanganate in neutral solution oxidizes it to nitrobenzene; in alkaline solution to azobenzene, ammonia, and oxalic acid; in acid solution to aniline black. Hypochlorous acid gives 4-aminophenol and para-amino diphenylamine.[18] Oxidation with persulfate affords a variety of polyanilines. These polymers exhibit rich redox and acid-base properties.

Electrophilic reactions at ortho- and para- positions

[edit]Like phenols, aniline derivatives are highly susceptible to electrophilic substitution reactions. Its high reactivity reflects that it is an enamine, which enhances the electron-donating ability of the ring. For example, reaction of aniline with sulfuric acid at 180 °C produces sulfanilic acid, H2NC6H4SO3H.

If bromine water is added to aniline, the bromine water is decolourised and a white precipitate of 2,4,6-tribromoaniline is formed. To generate the mono-substituted product, a protection with acetyl chloride is required:

The reaction to form 4-bromoaniline is to protect the amine with acetyl chloride, then hydrolyse back to reform aniline.

The largest scale industrial reaction of aniline involves its alkylation with formaldehyde. An idealized equation is shown:

- 2 C6H5NH2 + CH2O → CH2(C6H4NH2)2 + H2O

The resulting diamine is the precursor to 4,4'-MDI and related diisocyanates.

Reactions at nitrogen

[edit]Basicity

[edit]Aniline is a weak base. Aromatic amines such as aniline are, in general, much weaker bases than aliphatic amines. Aniline reacts with strong acids to form the anilinium (or phenylammonium) ion (C6H5−NH+3).[20]

Traditionally, the weak basicity of aniline is attributed to a combination of inductive effect from the more electronegative sp2 carbon and resonance effects, as the lone pair on the nitrogen is partially delocalized into the pi system of the benzene ring. (see the picture below):

Missing in such an analysis is consideration of solvation. Aniline is, for example, more basic than ammonia in the gas phase, but ten thousand times less so in aqueous solution.[21]

Acylation

[edit]Aniline reacts with acyl chlorides such as acetyl chloride to give amides. The amides formed from aniline are sometimes called anilides, for example CH3−C(=O)−NH−C6H5 is acetanilide. At high temperatures aniline and carboxylic acids react to give the anilides.[22]

N-Alkylation

[edit]N-Methylation of aniline with methanol at elevated temperatures over acid catalysts gives N-methylaniline and N,N-dimethylaniline:

- C6H5NH2 + 2 CH3OH → C6H5N(CH3)2 + 2H2O

N-Methylaniline and N,N-dimethylaniline are colorless liquids with boiling points of 193–195 °C and 192 °C, respectively. These derivatives are of importance in the color industry.

Carbon disulfide derivatives

[edit]Boiled with carbon disulfide, it gives sulfocarbanilide (diphenylthiourea) (S=C(−NH−C6H5)2), which may be decomposed into phenyl isothiocyanate (C6H5−N=C=S), and triphenyl guanidine (C6H5−N=C(−NH−C6H5)2).[18]

Diazotization

[edit]Aniline and its ring-substituted derivatives react with nitrous acid to form diazonium salts. One example is benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate. Through these intermediates, the amine group can be converted to a hydroxyl (−OH), cyanide (−CN), or halide group (−X, where X is a halogen) via Sandmeyer reactions. This diazonium salt can also be reacted with NaNO2 and phenol to produce a dye known as benzeneazophenol, in a process called coupling. The reaction of converting primary aromatic amine into diazonium salt is called diazotisation. In this reaction primary aromatic amine is allowed to react with sodium nitrite and 2 moles of HCl, which is known as "ice cold mixture" because the temperature for the reaction was as low as 0.5 °C. The benzene diazonium salt is formed as major product alongside the byproducts water and sodium chloride.

Other reactions

[edit]It reacts with nitrobenzene to produce phenazine in the Wohl–Aue reaction. Hydrogenation gives cyclohexylamine.

Being a standard reagent in laboratories, aniline is used for many niche reactions. Its acetate is used in the aniline acetate test for carbohydrates, identifying pentoses by conversion to furfural. It is used to stain neural RNA blue in the Nissl stain.[citation needed]

In addition, aniline is the starting component in the production of diglycidyl aniline.[23] Epichlorohydrin is the other main ingredient.[23][24]

Uses

[edit]Aniline is predominantly used for the preparation of methylenedianiline and related compounds by condensation with formaldehyde. The diamines are condensed with phosgene to give methylene diphenyl diisocyanate, a precursor to urethane polymers.[7]

Other uses include rubber processing chemicals (9%), herbicides (2%), and dyes and pigments (2%).[25] As additives to rubber, aniline derivatives such as phenylenediamines and diphenylamine, are antioxidants. Illustrative of the drugs prepared from aniline is paracetamol (acetaminophen, Tylenol). The principal use of aniline in the dye industry is as a precursor to indigo, the blue of blue jeans.[7]

Aniline oil is also used for mushroom identification. Kerrigan's 2016 Agaricus of North America P45: (Referring to Schaffer's reaction) "In fact I recommend switching to the following modified test. Frank (1988) developed an alternative formulation in which aniline oil is combined with glacial acetic acid (GAA, essentially distilled vinegar) in a 50:50 solution. GAA is a much safer, less reactive acid. This single combined reagent is relatively stable over time. A single spot or line applied to the pileus (or other surface). In my experience the newer formulation works as well as Schaffer's while being safer and more convenient."[26]

History

[edit]Aniline was first isolated in 1826 by Otto Unverdorben by destructive distillation of indigo.[27] He called it Crystallin. In 1834, Friedlieb Runge isolated a substance from coal tar that turned a beautiful blue color when treated with chloride of lime. He named it kyanol or cyanol.[28] In 1840, Carl Julius Fritzsche (1808–1871) treated indigo with caustic potash and obtained an oil that he named aniline, after an indigo-yielding plant, anil (Indigofera suffruticosa).[29][30] In 1842, Nikolay Nikolaevich Zinin reduced nitrobenzene and obtained a base that he named benzidam.[31] In 1843, August Wilhelm von Hofmann showed that these were all the same substance, known thereafter as phenylamine or aniline.[32]

Synthetic dye industry

[edit]In 1856, while trying to synthesise quinine, von Hofmann's student William Henry Perkin discovered mauveine. Mauveine quickly became a commercial dye. Other synthetic dyes followed, such as fuchsin, safranin, and induline. At the time of mauveine's discovery, aniline was expensive. Soon thereafter, applying a method reported in 1854 by Antoine Béchamp,[33] it was prepared "by the ton".[34] The Béchamp reduction enabled the evolution of a massive dye industry in Germany. Today, the name of BASF, originally Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (English: Baden Aniline and Soda Factory), now the largest chemical supplier, echoes the legacy of the synthetic dye industry, built via aniline dyes and extended via the related azo dyes. The first azo dye was aniline yellow.[35]

Developments in medicine

[edit]In the late 19th century, derivatives of aniline such as acetanilide and phenacetin emerged as analgesic drugs, with their cardiac-suppressive side effects often countered with caffeine.[36] Also in the late 19th century, Ehrlich found that the aniline dye methylene blue works as an antimalarial drug. He hypothesized that dyes that selectively stain pathogens over tissue would prefentially harm pathogens, leading to his "magic bullet" concept.[37]

During the first decade of the 20th century, while trying to modify synthetic dyes to treat African sleeping sickness, Paul Ehrlich – who had coined the term chemotherapy for his 'magic bullet' approach to medicine – failed and switched to modifying Béchamp's atoxyl, the first organic arsenical drug, and serendipitously obtained a treatment for syphilis – salvarsan – the first successful chemotherapy agent. Salvarsan's targeted microorganism, not yet recognized as a bacterium, was still thought to be a parasite, and medical bacteriologists, believing that bacteria were not susceptible to the chemotherapeutic approach, overlooked Alexander Fleming's report in 1928 on the effects of penicillin.[38]

In 1932, Bayer sought medical applications of its dyes. Gerhard Domagk identified as an antibacterial a red azo dye, introduced in 1935 as the first antibacterial drug, prontosil, soon found at Pasteur Institute to be a prodrug degraded in vivo into sulfanilamide – a colorless intermediate for many, highly colorfast azo dyes – already with an expired patent, synthesized in 1908 in Vienna by the researcher Paul Gelmo for his doctoral research.[38] By the 1940s, over 500 related sulfa drugs were produced.[38] Medications in high demand during World War II (1939–45), these first miracle drugs, chemotherapy of wide effectiveness, propelled the American pharmaceutics industry.[39] In 1939, at Oxford University, seeking an alternative to sulfa drugs, Howard Florey developed Fleming's penicillin into the first systemic antibiotic drug, penicillin G. (Gramicidin, developed by René Dubos at Rockefeller Institute in 1939, was the first antibiotic, yet its toxicity restricted it to topical use.) After World War II, Cornelius P. Rhoads introduced the chemotherapeutic approach to cancer treatment.[40]

Rocket fuel

[edit]Some early American rockets, such as the Aerobee and WAC Corporal, used a mixture of aniline and furfuryl alcohol as a fuel, with nitric acid as an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic, igniting on contact between fuel and oxidizer. It is also dense, and can be stored for extended periods. Aniline was later replaced by hydrazine.[41]

Toxicology and testing

[edit]Aniline is toxic by inhalation of the vapour, ingestion, or percutaneous absorption.[42][43] The IARC lists it in Group 2A (Probably carcinogenic to humans), and it has specifically been linked to bladder cancer.[44] Aniline has been implicated as one possible cause of forest dieback.[45]

Many methods exist for the detection of aniline.[46]

Oxidative DNA damage

[edit]Exposure of rats to aniline can elicit a response that is toxic to the spleen, including a tumorigenic response.[47] Rats exposed to aniline in drinking water, showed a significant increase in oxidative DNA damage to the spleen, detected as a 2.8-fold increase in 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in their DNA.[47] Although the base excision repair pathway was also activated, its activity was not sufficient to prevent the accumulation of 8-OHdG. The accumulation of oxidative DNA damages in the spleen following exposure to aniline may increase mutagenic events that underlie tumorigenesis.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. 416, 668. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

Aniline, for C6H5-NH2, is the only name for a primary amine retained as a preferred IUPAC name for which full substitution is permitted on the ring and the nitrogen atom. It is a Type 2a retained name; for the rules of substitution see P-15.1.8.2. Substitution is limited to substituent groups cited as prefixes in accordance with the seniority of functional groups explicitly expressed or implied in the functional parent compound name. The name benzenamine may be used in general nomenclature.

- ^ a b c d e NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0033". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Vollhardt, P.; Schore, Neil (2018). Organic Chemistry (8th ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 1031. ISBN 9781319079451.

- ^ a b c "Aniline". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Aniline". cameochemicals.noaa.gov. US NOAA Office of Response and Restoration. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ^ "aniline". Etymonline. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Kahl, Thomas; Schröder, K. W.; Lawrence, F. R.; Elvers, Barbara; Höke, Hartmut; Pfefferkorn, R.; Marshall, W. J. (2007). "Aniline". In Ullmann, Fritz (ed.). Ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. Wiley: New York. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_303. ISBN 978-3-527-20138-9. OCLC 11469727.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Zhang, Huaiyu; Jiang, Xiaoyu; Wu, Wei; Mo, Yirong (April 28, 2016). "Electron conjugation versus π-π repulsion in substituted benzenes: why the carbon-nitrogen bond in nitrobenzene is longer than in aniline". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 18 (17): 11821–11828. Bibcode:2016PCCP...1811821Z. doi:10.1039/c6cp00471g. ISSN 1463-9084. PMID 26852720.

- ^ Raczyńska, Ewa D.; Hallman, Małgorzata; Kolczyńska, Katarzyna; Stępniewski, Tomasz M. (2010-07-12). "On the Harmonic Oscillator Model of Electron Delocalization (HOMED) Index and its Application to Heteroatomic π-Electron Systems". Symmetry. 2 (3): 1485–1509. Bibcode:2010Symm....2.1485R. doi:10.3390/sym2031485. ISSN 2073-8994.

- ^ G. M. Wójcik "Structural Chemistry of Anilines" in Anilines (Patai's Chemistry of Functional Groups), S. Patai, Ed. 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0385.

- ^ Sorriso, S. (1982). "Structural chemistry". Amino, Nitrosco and Nitro Compounds and Their Derivatives: Vol. 1 (1982). pp. 1–51. doi:10.1002/9780470771662.ch1. ISBN 9780470771662.

- ^ a b Alabugin, Igor V. (2016). Stereoelectronic effects : a bridge between structure and reactivity. Chichester, UK. ISBN 978-1-118-90637-8. OCLC 957525299.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Alabugin, Igor V.; Manoharan, Mariappan; Buck, Matthew; Clark, Ronald J. (July 2007). "Substituted anilines: The tug-of-war between pyramidalization and resonance inside and outside of crystal cavities". Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 813 (1–3): 21–27. doi:10.1016/j.theochem.2007.02.016.

- ^ Carey, Francis A. (2008). Organic chemistry (7th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 9780073047874. OCLC 71790138.

- ^ US3136818A, Heinrich, Sperber; Guenter, Poehler & Joachim, Pistor Hans et al., "Production of aniline", issued 1964-06-09

- ^ Westerhaus, Felix A.; Jagadeesh, Rajenahally V.; Wienhöfer, Gerrit; Pohl, Marga-Martina; Radnik, Jörg; Surkus, Annette-Enrica; Rabeah, Jabor; Junge, Kathrin; Junge, Henrik; Nielsen, Martin; Brückner, Angelika; Beller, Matthias (2013). "Heterogenized Cobalt Oxide Catalysts for Nitroarene Reduction by Pyrolysis of Molecularly Defined Complexes". Nature Chemistry. 5 (6): 537–543. Bibcode:2013NatCh...5..537W. doi:10.1038/nchem.1645. PMID 23695637. S2CID 3273484.

- ^ Porter, H. K. (2011), "The Zinin Reduction of Nitroarenes", Organic Reactions, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 455–481, doi:10.1002/0471264180.or020.04, ISBN 978-0-471-26418-7, retrieved 2022-02-01

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 48.

- ^ "Aniline synthesis by amination (Arylation)".

- ^ McMurry, John E. (1992). Organic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-16218-5.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Carl N. Webb (1941). "Benzanilide". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 82.

- ^ a b Panda, Dr H (2019). Epoxy Resins Technology Handbook (Manufacturing Process, Synthesis, Epoxy Resin Adhesives and Epoxy Coatings (2nd ed.). Asia Pacific Business Press Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-8178331829.

- ^ Jung, Woo-Hyuk; Ha, Eun-Ju; Chung, Il doo; Lee, Jang-Oo (2008-08-01). "Synthesis of aniline-based azopolymers for surface relief grating". Macromolecular Research. 16 (6): 532–538. doi:10.1007/BF03218555. ISSN 2092-7673. S2CID 94372490.

- ^ "Aniline". The Chemical Market Reporter. Archived from the original on 2002-02-19. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Kerrigan, Richard (2016). Agaricus of North America. NYBG Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-89327-536-5.

- ^ Otto Unverdorben (1826). "Ueber das Verhalten der organischen Körper in höheren Temperaturen" [On the behaviour of organic substances at high temperatures]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 8 (11): 397–410. Bibcode:1826AnP....84..397U. doi:10.1002/andp.18260841109.

- ^ F. F. Runge (1834) "Ueber einige Produkte der Steinkohlendestillation" (On some products of coal distillation), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 31: 65–77 (see page 65), 513–524; and 32: 308–332 (see page 331).

- ^ J. Fritzsche (1840) "Ueber das Anilin, ein neues Zersetzungsproduct des Indigo" (On aniline, a new decomposition product of indigo), Bulletin Scientifique [publié par l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de Saint-Petersbourg], 7 (12): 161–165. Reprinted in:

- J. Fritzsche (1840) "Ueber das Anilin, ein neues Zersetzungsproduct des Indigo", Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie, 36 (1): 84–90.

- J. Fritzsche (1840) "Ueber das Anilin, ein neues Zersetzungsproduct des Indigo", Journal für praktische Chemie, 20: 453–457. In a postscript to this article, Erdmann (one of the journal's editors) argues that aniline and the "cristallin", which was found by Unverdorben in 1826, are the same substance; see pages 457–459.

- ^ synonym I anil, ultimately from Sanskrit "nīla", dark-blue.

- ^ N. Zinin (1842). "Beschreibung einiger neuer organischer Basen, dargestellt durch die Einwirkung des Schwefelwasserstoffes auf Verbindungen der Kohlenwasserstoffe mit Untersalpetersäure" (Description of some new organic bases, produced by the action of hydrogen sulfide on compounds of hydrocarbons and hyponitric acid [H2N2O3]), Bulletin Scientifique [publié par l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de Saint-Petersbourg], 10 (18): 272–285. Reprinted in: N. Zinin (1842) "Beschreibung einiger neuer organischer Basen, dargestellt durch die Einwirkung des Schwefelwasserstoffes auf Verbindungen der Kohlenwasserstoffe mit Untersalpetersäure", Journal für praktische Chemie, 27 (1): 140–153. Benzidam is named on page 150.

Fritzsche, Zinin's colleague, soon recognized that "benzidam" was actually aniline. See: Fritzsche (1842) Bulletin Scientifique, 10: 352. Reprinted as a postscript to Zinin's article in: J. Fritzsche (1842) "Bemerkung zu vorstehender Abhandlung des Hrn. Zinin" (Comment on the preceding article by Mr. Zinin), Journal für praktische Chemie, 27 (1): 153.

See also: (Anon.) (1842) "Organische Salzbasen, aus Nitronaphtalose und Nitrobenzid mittelst Schwefelwasserstoff entstehend" (Organic bases originating from nitronaphthalene and nitrobenzene via hydrogen sulfide), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 44: 283–287. - ^ August Wilhelm Hofmann (1843) "Chemische Untersuchung der organischen Basen im Steinkohlen-Theeröl" (Chemical investigation of organic bases in coal tar oil), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 47: 37–87. On page 48, Hofmann argues that krystallin, kyanol, benzidam, and aniline are identical.

- ^ A. Béchamp (1854) "De l'action des protosels de fer sur la nitronaphtaline et la nitrobenzine. Nouvelle méthode de formation des bases organiques artificielles de Zinin" (On the action of iron protosalts on nitronaphthaline and nitrobenzene. New method of forming Zinin's synthetic organic bases.), Annales de Chemie et de Physique, 3rd series, 42: 186 – 196. (Note: In the case of a metal having two or more distinct oxides (e.g., iron), a "protosalt" is an obsolete term for a salt that is obtained from the oxide containing the lowest proportion of oxygen to metal; e.g., in the case of iron, which has two oxides – iron (II) oxide (FeO) and iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3) – FeO is the "protoxide" from which protosalts can be made. See: Wiktionary: protosalt.)

- ^ Perkin, William Henry. 1861-06-08. "Proceedings of Chemical Societies: Chemical Society, Thursday, May 16, 1861". The Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science. Retrieved on 2007-09-24.

- ^ Auerbach G, "Azo and naphthol dyes", Textile Colorist, 1880 May;2(17):137-9, p 138.

- ^ Wilcox RW, "The treatment of influenza in adults", Medical News, 1900 Dec 15;77():931-2, p 932.

- ^ Wainwright, Mark (January 2008). "Dyes in the development of drugs and pharmaceuticals". Dyes and Pigments. 76 (3): 582–589. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2007.01.015.

- ^ a b c D J Th Wagener, The History of Oncology (Houten: Springer, 2009), pp 150–1.

- ^ John E Lesch, The First Miracle Drugs: How the Sulfa Drugs Transformed Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp 202–3.

- ^ "Medicine: Spoils of War". Time. 15 May 1950. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ Brian Burnell. 2016. http://www.nuclear-weapons.info/cde.htm#Corporal SSM

- ^ Muir, GD (ed.) 1971, Hazards in the Chemical Laboratory, The Royal Institute of Chemistry, London.

- ^ The Merck Index. 10th ed. (1983), p.96, Rahway: Merck & Co.

- ^ Tanaka, Takuji; Miyazawa, Katsuhito; Tsukamoto, Testuya; Kuno, Toshiya; Suzuki, Koji (2011). "Pathobiology and Chemoprevention of Bladder Cancer". Journal of Oncology. 2011: 1–23. doi:10.1155/2011/528353. PMC 3175393. PMID 21941546.

- ^ Krahl-Urban, B., Papke, H.E., Peters, K. (1988) Forest Decline: Cause-Effect Research in the United States of North America and Federal Republic of Germany. Germany: Assessment Group for Biology, Ecology and Energy of the Julich Nuclear Research Center.

- ^ Basic Analytical Toxicology (1995), R. J. Flanagan, S. S. Brown, F. A. de Wolff, R. A. Braithwaite, B. Widdop: World Health Organization

- ^ a b Ma, Huaxian; Wang, Jianling; Abdel-Rahman, Sherif Z.; Boor, Paul J.; Khan, M. Firoze (2008). "Oxidative DNA damage and its repair in rat spleen following subchronic exposure to aniline". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 233 (2): 247–253. Bibcode:2008ToxAP.233..247M. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.010. PMC 2614128. PMID 18793663.

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Aniline", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–48

External links

[edit]- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 47–48 short=x

- International Chemical Safety Card 0011

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazrds

- Aniline electropolymerisation

Aniline

View on GrokipediaProperties

Physical properties

Aniline is a colorless to pale yellow oily liquid at room temperature, with a characteristic amine odor often described as resembling rotten fish or musty.[1] It has a molecular weight of 93.13 g/mol and appears denser than water.[3] Upon prolonged exposure to air and light, it gradually darkens to a reddish-brown color due to oxidation, forming colored impurities without significant loss in purity.[11] Key thermodynamic properties include a melting point of -6 °C and a boiling point of 184 °C at standard pressure.[11] The density is 1.022 g/mL at 25 °C, and the vapor pressure is 0.6 mmHg at 20 °C, with vapors heavier than air (vapor density 3.22 relative to air).[11] The refractive index is 1.586 at 20 °C, and the dynamic viscosity is 3.7 mPa·s at 25 °C.[11][12]| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Flash point | 70 °C | Closed cup |

| Autoignition temperature | 615 °C | - |