Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

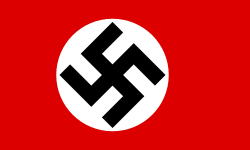

Austria within Nazi Germany

View on WikipediaKey Information

| History of Austria |

|---|

|

|

|

Austria was part of Nazi Germany from 13 March 1938, an event known as the Anschluss, until 27 April 1945, when Allied-occupied Austria declared independence from Nazi Germany.

Nazi Germany's troops entering Austria in 1938 received the enthusiastic support of most of the population.[1] Throughout World War II, 950,000 Austrians fought for the German armed forces. Other Austrians participated in the Nazi administration, from Nazi death camp personnel to senior Nazi leadership including Hitler; the majority of the bureaucrats who implemented the Final Solution were Austrian.[2][3]

After the Anschluss in 1938, Nazi Germany sought to eliminate Austria's separate national and cultural identity by portraying it as an inseparable part of the Greater Germanic Reich. The Austrian flag, anthem, and national symbols were banned, and the use of the name "Austria" was replaced with "Ostmark". From 1942, even this term was considered too closely associated with the former Austrian state, and the official designation for the area was changed to "Alpen- und Donau-Reichsgaue". Education, propaganda, and public institutions were reoriented to promote German nationalism and suppress Austrian traditions. The regime aimed to erase any notion of an independent Austrian state or culture.

After World War II, many Austrians sought comfort in the myth of Austria as being the first victim of the Nazis.[4] Although the Nazi Party was promptly banned, Austria did not have the same thorough process of denazification that was imposed on postwar West Germany. Lacking outside pressure for political reform, factions of Austrian society tried for a long time to advance the view that the Anschluss was only an imposition of rule by Nazi Germany.[5] By 1992, the subject of the small minority who formed an Austrian resistance, versus the vast majority of Austrians who participated in the German war machine, had become a prominent matter of public discourse.[6]

Early history

[edit]

The origins of Nazism in Austria have been disputed and continue to be debated.[7] Professor Andrew Gladding Whiteside regarded the emergence of an Austrian variant of Nazism as the product of the German-Czech conflict of the multi-ethnic Austrian Empire and rejected the view that it was a precursor of German Nazism.[8]

In 1918, at the end of World War I, with the breakup of the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire, and with the abolition of the Habsburg monarchy, there were three major political groups competing with one another in the young republic of Austria: the Social Democratic Party of Austria (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, SDAPÖ), Christian Social Party (Christlichsoziale Partei, CS), and the nationalist Great German Union (Großdeutsche Vereinigung), which became the Greater German People's Party (Großdeutsche Volkspartei, or GVP) in 1920. At the time, smaller parties such as the Communist Party of Austria (Kommunistische Partei Österreichs, or KPÖ) and the Austrian National Socialists (Deutsche Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei, or DNSAP) were neither present in the Reichsrat (Imperial Council) nor the Nationalrat (National Council).

SDAP, GVP, and DNSAP clearly, although for different reasons, favoured a union of German Austria with the German state, which was also a republic by that time (Weimar Republic). The CS also tended to favour the union, but differed at first on a different subject – they were split on the idea of continuing the monarchy instead of a republic. Whereas only the KPÖ decidedly spoke against the annexation in the course of the 1920s and 1930s, the monarchists originally spoke up against the annexation and later turned to favor it, after the Bavarian Soviet Republic had failed, and Germany had a conservative government. The Treaty of Saint-Germain, signed 10 September 1919 by Karl Renner (SDAPÖ), first chancellor of the republic, clearly forbade any union with Germany, abolished the monarchy, and clearly stated the First Austrian Republic as an independent country.[9]

First Austrian Republic

[edit]The First Austrian Republic angered many Austrian pan-Germans who made the claim that the republic violated the Fourteen Points that were announced by United States President Woodrow Wilson during peace talks, specifically the right to "self-determination" of all nations.[10]

Life and politics in the early years were marked by serious economic problems (the loss of industrial areas and natural resources in the now independent Czechoslovakia), hyperinflation and a constantly increasing tension between the different political groups. From 1918 to 1920 the government was led by the Social Democratic Party and later by the Christian Social Party in coalition with the German nationalists.

Plebiscites [11] in Austrian Tyrol and Salzburg in 1921, saw majorities of 98.77%[12] and 99.11%[13] voted for a unification with Germany.

On 31 May 1922, prelate Ignaz Seipel became Chancellor of the Christian Social government. He succeeded in improving the economic situation with the financial help of the League of Nations (monetary reform). Ideologically, Seipel was clearly anti-communist and did everything in his power to reduce, as far as possible, the influence of the Social Democrats – both sides saw this as a conflict between two social classes.

The military of Austria was restricted to 30,000 men by the allies and the police force was poorly equipped. Already by 1918 the first homeguards were established like the Kärntner Abwehrkampf. In 1920 in Tirol the first Heimwehr was put in duty under the command of Richard Steidle with the help of the Bavarian organisation Escherich. Soon other states followed. In 1923 members of the Monarchist "Ostara" shot a worker dead and the Social Democrats founded their own protective organization. Other paramilitary groups were then formed from former active soldiers and members of the Roman Catholic Church. The Vaterländische Schutzbund ('Protectors of the Fatherland') were National Socialists. Later they started the Austrian Sturmabteilung (SA).

The German Workers' Party had already been founded in Bohemia as early as 1903. It was then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It supported German nationalism and anti-clericalism, but at first was not particularly antisemitic. This party stood mainly for making Austria and the Austrian Germans a part of Germany. In 1909 lawyer, Walter Riehl joined the party and he became leader in 1918. Soon after that the name was changed to the German National Socialist Workers' Party (Deutsche Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei' DNSAP). After the fall of the monarchy, the party split into a Czechoslovakian party and an Austrian party under Riehl. From 1920 onwards this Austrian party cooperated closely with the Munich formed German Workers' Party (DAP) and then the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; NSDAP), which Adolf Hitler led after 1921. In 1923 Riehl's party had about 23,000 members and was a marginal factor in Austrian politics. In 1924 there was another split and Karl Schulz led a splinter group. The two opposed each other. In 1926 Richard Suchenwirth founded the Austrian branch of Hitler's German National Socialist party in Vienna. Around that time Benito Mussolini formed his Fascist dictatorship in Italy and became an important ally of the far right.

The Austrian National Socialists linked to Hitler (Nazis) got only 779 votes in the 1927 General Election. The strongest grouping besides the Social Democrats was the Unity Coalition led by the Christian Social Party but including German Nationalists and the groups of Riehl and Schulz. In the course of these years there were frequent serious acts of violence between the various armed factions and people were regularly killed. In the General Election of 1930, the Social Democrats were the largest single party. The Christian Social Party came second but stayed in office in a coalition with smaller parties. The Austrian National Socialists linked to Hitler's NSDAP received only 3.6% of the votes and failed to enter Parliament. In the following years the Nazis gained votes at the expense of the various German national groups, which also wanted unity with Germany. After 1930 Hitler's NSDAP doubled its membership every year because of the economic crisis. One of their slogans was, "500,000 Unemployed – 400,000 Jews – Simple way out; vote National Socialist".

Dictatorship, civil war and banning National Socialism

[edit]

The Christian Social Party had ruled from 1932 and Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß had led them from 1932. The Social Democrats were no longer their only threat. The previous chancellor and priest Ignaz Seipel had worked towards an authoritarian state. Seipel based this on the Papal Encyclicals, Rerum novarum (1891) and Quadragesimo anno (1931). Abolition of the parliamentary system was necessary for this. A crisis in the Austrian parliament on the 4 May 1933 gave Dollfuß the opportunity he wanted.

Later in May 1933 the Christian Social Union was converted to the Patriotic Front. The Patriotic Front was a political organisation, supposedly above partisan considerations, Roman Catholic and vehemently anti-Marxist. It purported to represent all Austrians who were true to their native land. Within a week the Austrian Communist Party was banned, and before the end of the month the republican paramilitary organisation and Freethinkers Organisations were banned along with numerous other groups. Nazis failed to get more than 25% of the votes in local elections in most areas. In Zwettl and Innsbruck however they got more than 40%, and they tried to lever this into a basis for agitation against the ruling Patriotic Front. Nazi supporters generated a wave of terrorism which crested in early June with four deaths and 48 people injured.

In Germany Hitler became Chancellor early in 1933. The Social Democrats deleted any intention to cooperate with Germany from its party programme. Nazis had fled to Bavaria after their party was banned in Austria and founded there the Austrian Legion. The Nazis there had military style camps and military training. Nazi terrorists in Austria received financial, logistic and material support from Germany. The German Government subjected Austria to systematic agitation. After the expulsion of the Bavarian Minister of Justice in May 1933 German citizens were required to pay a thousand marks to the German Government before travelling to Austria. The Austrian Nazi Party was banned in June after a hand grenade attack in Krems. Nazi terrorism abated after that though five more people were killed and 52 injured by the end of the year.

On 12 February 1934 there was a violent confrontation in Linz with serious consequences. Members of a paramilitary group acting to assist the police wanted to enter a building belonging to the Social Democrats or a party member's home. They wanted to find any weapons belonging to the Social Democrat paramilitary which had by then been banned. Violence spread to the whole country and developed into civil war. The police and their paramilitary supporters together with the army won the confrontation by the 14 February. There were many arrests. Constitutional courts were abolished, trade unions and the Social Democrat Party were banned, and the death penalty was reintroduced. After political opposition had been suppressed the Austrian Republic was transformed into the Ständestaat. The authoritarian |Maiverfassung (May Constitution) was proclaimed on 1 May.

Attempted Nazi coup and growing German influence

[edit]From the start of 1934 there was a new wave of Nazi terrorist attacks in Austria. This time government institutions were targeted far more than individuals. In the first half of 1934, 17 people were killed and 171 injured. On 25 July the Nazis attempted a coup under the leadership of the Austrian SS. About 150 SS personnel forced their way into the Chancellor's office in Vienna. Dollfuß was shot and died a few hours later from his wounds. Another group occupied the building of the Austrian National Radio and forced a statement that the Government of Dollfuß had fallen and Anton Rintelen was the new head of government. Anton Rintelen belonged to the Christian Social Party but is suspected of Nazi sympathy. This false report was intended to start a Nazi uprising throughout the country but it was only partially successful.

There was considerable fighting in parts of Carinthia, Styria and Upper Austria and limited resistance in Salzburg. In Carinthia and Styria the fighting lasted from the 27 to 30 July. Some members of the Austrian Legion tried to push out from Bavaria over the Mühlviertel, a part of Upper Austria, and towards Linz. They were forced back to the frontier at Kollerschlag. On 26 July a German courier was arrested at the Kollerschlag pass in Upper Austria. He had with him documented instructions for the revolt. This so-called Kollerschlag Document demonstrated the connection of the July revolt to Bavaria clearly.[14]

The army, the gendarmerie and the police put down revolt with heavy casualties. On the government side there were up to 104 deaths and 500 injuries. On the rebel side there were up to 140 deaths and 600 injuries. Thirteen rebels were executed and 4,000 people were imprisoned without trial. Many thousand supporters of the Nazi Party were arrested. Up to 4000 fled over the border to Germany and Yugoslavia. Kurt Schuschnigg became the new Chancellor.

In Bavaria many sections of the Austrian Legion were officially closed. In reality they were only pushed further north and renamed, “North-West Assistance”. Hitler ordered troops to the Austrian border, prepared for a full-scale military assault into Austria to support the National Socialists. Fascist Italy was more closely tied to the regime in Vienna and sent troops to the Austrian border at Brenner to deter German troops from a possible invasion of Austria. Hitler was at first torn between going ahead with the invasion, or pulling off the border. Hitler realized that the German Army was not prepared to take on both the Austrians and the Italian Army. Hitler ordered the force to be pulled off the Austrian border. The German government stated that it had nothing to do with the revolt. Germany only admitted that it was trying to subvert the Austrian political system through trusted people. They continued to support the illegal Nazi party but sympathizers who did not belong to the party were more significant. This included among others Taras Borodajkewycz, Edmund Glaise-Horstenau, Franz Langoth, Walther Pembauer and Arthur Seyß-Inquart.

To put Schuschnigg's mind at ease, Hitler declared to the Reichstag in May 1935: "Germany neither intends nor wishes to interfere in the internal affairs of Austria, to annex Austria or to conclude an Anschluss".[15]

Italy began its conquest of Abyssinia (the Second Italo-Abyssinian War) in October 1935. After that Mussolini was internationally isolated and strengthened his relations with Hitler. The ruling Austrian Patriotic Front lost an important ally. Despite the murder of Engelbert Dollfuß, his successor Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg had to improve relations with the German government. Like his predecessor he wanted to maintain the independence of Austria. He saw Austria as the second German state and the better state as it was founded on Roman Catholicism.

In July 1936 Schuschnigg accepted the July Agreement with Germany. Imprisoned Nazis were released and some Nazi newspapers, which had been banned, were allowed into Austria. The Nazi Party remained banned. Schuschnigg undertook further to allow two people whom the Nazis trusted into the Government. Edmund Glaise-Horstenau became Minister for National Affairs and Guido Schmidt became Secretary of State in the Foreign Ministry. Arthur Seyß-Inquart was taken into the legislative Council of State. Germany rescinded the requirement for a payment of a thousand marks for entry into Austria. The transformation of the Federal State through Nazis was furthered more in 1937 when it became possible for them to join the Patriotic Front. Throughout Austria political units were set up and some were led by Nazis. This was a legal disguise for the reorganization.

The native Austrian-born Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf on the first page of the book: "German Austria must return to the great German motherland" and "common blood belongs in a common Reich". From 1937 it was clear to the Nazis that it would not be long before Austria was going to be incorporated into Nazi Germany. His strategy, outlined in the Hossbach Memorandum, included the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland part of Czechoslovakia to gain Lebensraum ("living space"). Hitler told Goebbels in the late summer that Austria would sooner or later be taken "by force".[16]

In February 1938 Franz von Papen, the German ambassador in Vienna arranged a meeting between Hitler and Schuschnigg at Obersalzberg in Gaden in Bavaria. Hitler threatened repeatedly to invade Austria and forced Schuschnigg to implement a range of measures favourable to Austrian Nazism. The Agreement of Gaden guaranteed the Austrian Nazi Party political freedom and assisted Arthur Seyß-Inquart in becoming Home Secretary (Innenminister). Schuschnigg endeavoured to maintain Austrian national integrity despite steadily increasing German influence. On 9 March 1938 he announced that he wanted to hold a consultative referendum on the independence of Austria on the following Sunday. Hitler responded by mobilizing the 8th Army for the planned invasion. Edmund Glaise-Horstenau who was at the time in Berlin brought Hitler's ultimatum from there and Göring reinforced it with a telephone message to Schuschnigg. The German government demanded the postponement or abandonment of the referendum. Schuschnigg conceded on the afternoon of 11 March. Then Hitler demanded his resignation which happened on the same evening.

Annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany

[edit]

After Schuschnigg left office, the federal president Wilhelm Miklas asked Arthur Seyß-Inquart to form a new government as the Germans demanded. From 11 to 13 March he led the Austrian Government and completed the Anschluss. On the morning of 12 March heavily armed German troops and police crossed the Austrian frontier, in total about 25000. Large sections of the Austrian population were very pleased to see them. In Vienna, Aspern met Heinrich Himmler of the SS accompanied by many police and SS officials to take over the Austrian police. Supporters of the Austrian Nazi Party together with members of the SS and SA occupied public buildings and offices throughout Austria without a previously planned transition period. The formation of the Greater German Reich was announced from the balcony of the Council House in Linz. On the following day, 13 March 1938, the second session of the Government passed the “Reunification with Germany Law”. Federal President Miklas refused to endorse it and resigned. Seyß-Inquart was now functioning Head of State. He could make his own laws and publish them. Before the evening was over, Hitler signed a law which made Austria a German province.[17]

On 15 March Hitler, who had spent the previous two days in his birth town of Braunau am Inn, made a triumphal entry into Vienna and gave a speech on Heldenplatz in front of tens of thousands of cheering people, in which he boasted of his "greatest accomplishment": "As leader and chancellor of the German nation and Reich I announce to German history now the entry of my homeland into the German Reich."[a] Ernst Kaltenbrunner from Upper Austria was promoted SS-Brigadeführer and the leader of the SS-upper section Austria. Beginning on 12 March and during the subsequent weeks 72,000 people were arrested, primarily in Vienna, among them politicians of the First Republic, intellectuals and above all Jews. Jewish institutions were shuttered.

Josef Bürckel, previously Reichskommissar for the reunion of the Saar (protectorate), was appointed by Hitler to reorganize the Nazi Party in Austria[17] and on 13 March as "Reichskommissar for the reunification of Austria with the German Empire".[18]

In March 1938 the local Gauleiter of Gmunden, Upper Austria, gave a speech to the local Austrians and told them that the "traitors" of Austria were to be thrown into the newly opened Mauthausen concentration camp.[19] Overall 200,000 people were killed at the camp.[19]

The Anti-Romanyism sentiment of Nazi Germany was implemented initially most harshly in newly annexed Austria when between 1938 and 1939 the Nazis arrested around 2,000 Gypsy men whom were sent to Dachau and 1,000 Gypsy women whom were sent to Ravensbrück.[20] In late October 1939, all Austrian Gypsies were required to register themselves.[21] Between 1938–39 the Nazis carried out racial examinations against the Gypsy population.[21] Until 1941 the Nazis made a distinction between "pure Gypsies" and "Gypsy Mischlinge". However, Nazi racial research concluded that 90% of Gypsies were of mixed ancestry.[22] Thus, after 1942, the Nazis discriminated against the Gypsies on the same level as the Jews with a variety of discrimination laws.[22]

Plebiscite

[edit]

A referendum to ratify the annexation was set for 10 April, preceded by a major propaganda campaign. Hitler himself, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, and many other leading figures of the Nazi regime held speeches. The controlled press and radio campaigned for a Yes vote to the "Reunion of Germany and Austria". Prominent Austrians like Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, who signed a declaration of the bishops with Heil Hitler, and the Social Democrat Karl Renner promoted the approval. Austria's bishops endorsed the Anschluss.[2] In response to a request from the Nazi government, the day before the referendum, all the churches in Austria tolled their bells in support of Hitler.[2]

According to official records 99.73% voted Yes in Austria and in Germany 99.08% voted for the annexation.[23]

Excluded from the referendum were about 8% of the Austrian voters: about 200,000 Jews and roughly 177,000 Mischlinge (people with both Jewish and "Aryan" parents) and all those who had already been arrested for "racial" or political reasons.[24]

Antisemitism

[edit]

The antisemitism against Austrian Jews had a long history in Austria; mass antisemitic violence took place immediately after the Germans had crossed the border into Austria. On the day after the plebiscite, a British correspondent estimated that 100,000 Viennese were rampaging through the Jewish quarter shouting "Death to the Jews!"[2] In the wealthy district of Währing Jewish women were ordered to put on their fur coats and scrub the streets while officials urinated on them, as crowds of Austrians and Germans cheered.[2]

The process of Aryanization began straight away, about 1,700 motor vehicles were seized from their Jewish owners between 11 March and 10 August 1938. Until May 1939, the government seized about 44,000 apartments in Jewish possession.

Many were dispossessed of their shops and apartments, into which those who had robbed them moved, assisted by the SA and fanatics. Jews were forced to put on their best clothes and, on their hands and knees with brushes, to clean the sidewalks of anti-Anschluss slogans.

The Kristallnacht ("Night of Broken Glass") pogroms of November 1938 were especially brutal in Austria; most of Vienna's synagogues were burned in view of the public and fire departments.[1]

Antisemitism was widespread even in the highest government offices. Karl Renner, who was the first chancellor of republican Austria, had welcomed the Anschluss in 1938. After the war, Renner again became the Austrian head of state; he remained antisemitic, even with Jewish returnees and concentration camp survivors. Marko Feingold, survivor of the concentration camp and president of the Salzburg Jewish Community, stated in 2013: "Karl Renner, after all the first Federal President of the Second Republic, had long been known in the party as an anti-Semite. He didn't want us concentration campers in Vienna after the war and he also frankly said that Austria would not give anything back to them."[25][26][27] Despite his controversial actions, many locations in Austria continue to bear his name; he is also the namesake of the Karl Renner Prize.[28][29][30]

Austrian participation in the Holocaust and Nazi armed forces

[edit]The majority of the bureaucrats who implemented the Final Solution were Austrian.[2]

According to Thomas Berger, professor of international relations at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University, the people who were involved in the Final Solution were disproportionately Austrian. He has said, "Austria represented about 8 per cent of the population of the Third Reich, but about 13 per cent of the SS, about 40 per cent of the concentration camp personnel, and as much as 70 per cent of the people who headed the concentration camps were of Austrian background."[31]

Political scientist David Art of Tufts University also states that Austrians comprised 8 per cent of Nazi Germany's population, 13 percent of the SS and 40 per cent of the staff at death camps; but that 75 per cent of concentration camp commanders were Austrian.[32]

The largest concentration camp in Austria was the Mauthausen-Gusen complex, with more than 50 subcamps, among them the Ebensee concentration camp, KZ – Nebenlager Bretstein, Steyr-Münichholz subcamp and AFA-Werke. Mass murder was practised in Hartheim Castle near Linz, where the killing programme Action T4 (involuntary euthanasia) took place, and in Am Spiegelgrund clinic in Vienna, where more than 700 handicapped children were murdered.

Prior to the Anschluss, the Austrian Nazi party's military wing, the Austrian SS, was an active terrorist organization. After the Anschluss, Hitler's Austrian and German armies were fully integrated. During the war, 800,000 Austrians volunteered for Nazi Germany in the Wehrmacht and a further 150,000 Austrians joined up to the Nazi party's military wing, known as the Waffen-SS.[2]

Prominent Austrians in the Nazi regime

[edit]The following Austrians were among those playing an active part in the Nazi regime:

- Adolf Hitler was German Chancellor from 1933 to 1945 and Führer ('Leader') from 2 August 1934 to 30 April 1945.

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner replaced Heydrich in January 1943 as leader of Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA).

- Arthur Seyß-Inquart organized or covered several Nazi crimes in the Netherlands.

- Odilo Globocnik was SS and police leader from 1939 in Poland where he supervised the building of the four Nazi extermination camps in Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka and Majdanek. He was one of the main people responsible for murdering about 2 million Polish Jews (Aktion Reinhardt).

- Franz Josef Huber, Inspekteur der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD for the Reichsgaue Vienna, Lower Danube and Upper Danube.

- August Eigruber, Gauleiter of Reichsgau Upper Danube.

- Alexander Löhr, commander of Luftflotte 4, carried out the bombing of Belgrade in April 1941.

- Hermann Neubacher was an Austrian Nazi politician who held a number of diplomatic posts. During the Second World War, he was appointed as the leading German foreign ministry official for Greece and the Balkans (including Serbia, Albania and Montenegro).

- Lothar Rendulic was an army group commander in the Wehrmacht during World War II. Rendulic was one of three Austrians who rose to the rank of Generaloberst (colonel general) in the German armed forces. The other two were Alexander Löhr and Erhard Raus.

- Wolfgang Abel, professor of racial biology at the University of Berlin, was involved in compulsory sterilization of so-called "Rhineland Bastards". During the war, he carried out "racial analyses" on 7,000 Soviet prisoners of war on behalf of the high command of the army.

- Heinrich Gross wrote expertises about "unworthy lives" and carried out deadly experiments at Am Spiegelgrund with handicapped children.

- Alois Brunner was an Austrian Schutzstaffel (SS) officer who worked as Adolf Eichmann's assistant.

- Karl Silberbauer arrested Anne Frank in 1944.

- Otto Skorzeny SS-Obersturmbannführer in Waffen-SS.

- Edmund Glaise-Horstenau was an Austrian officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, last Vice-Chancellor of Austria before the 1938 Anschluss, a military historian, archivist, and general in the German Wehrmacht during the Second World War.

- The Austrian Gauleiter Hugo Jury, Franz Hofer and Friedrich Rainer also participated in Nazi crimes.

- Friedrich Franek general in Wehrmacht during World War II.

- Amon Göth commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp.

Austrian resistance

[edit]A small minority of the Austrian population actively participated in the resistance against Nazism.[6] The Austrian historian Helmut Konrad has estimated that out of an Austrian population of 6.8 million in 1938, there were around 100,000 Austrian opponents to the regime who were convicted and imprisoned, and an Austrian membership of the Nazi Party of 700,000.[33]

The Austrian resistance groups were often ideologically separated and reflected the spectrum of political parties before the war. In addition to armed resistance groups, there was a strong communist resistance group, groups close to the Catholic Church, Habsburg groups and individual resistance groups in the German Wehrmacht. Most resistance groups were exposed by the Gestapo and the members were executed.

The most spectacular individual group of the Austrian resistance was the one around the priest Heinrich Maier. On the one hand, this very successful Catholic resistance group wanted to revive a Habsburg monarchy after the war (as planned by Winston Churchill and later fought by Joseph Stalin) and very successfully passed on plans and production facilities for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and aircraft (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.) to the Allies. With the location sketches of the production facilities, the Allied bombers were able to carry out precise air strikes and thus protect residential areas. In contrast to many other German resistance groups, the Maier group informed very early about the mass murder of Jews through its contacts with the Semperit factory near Auschwitz.[34][35][36][37][38]

"O5" was a sign of the Austrian resistance, where the 5 stands for E and OE is the abbreviation of Österreich with Ö as OE. This sign may be seen at the Stephansdom in Vienna.

Austrians in exile

[edit]From March to November 1938, 130,000 people emigrated legally or escaped illegally from Austria. Among the most famous emigrating artists, there were the composers Arnold Schönberg and Robert Stolz, the film-makers Leon Askin, Fritz Lang, Josef von Sternberg, Billy Wilder, Max Reinhardt, the actors Karl Farkas and Gerhard Bronner and the writers Hermann Broch, Robert Musil, Anton Kuh and Franz Werfel. Friedrich Torberg, who witnessed the German invasion ("Anschluss") in Prague, did not return to Vienna. Erich Fried flew with his mother to London after his father had been killed by the Gestapo in May 1938 during an interrogation. Stefan Zweig escaped via London, New York, Argentina and Paraguay to Brazil where he committed suicide in February 1942, together with his wife Charlotte Altmann. 1936 Nobel laureate in medicine Otto Loewi had to pay his prize money back before emigrating. Additional scientists going into exile were Sigmund Freud, Erwin Schrödinger, Kurt Gödel, Martin Buber, Karl Popper and Lise Meitner. Bruno Kreisky, who had to leave the country for political reasons and because of his Jewish origin, emigrated to Sweden. After his comeback, he served as Austrian Chancellor from 1970 to 1983.

Aftermath

[edit]In the first years after the war, many memorials were built in several places, commemorating the dead soldiers of World War II who allegedly fought for their country. For the victims of the Nazi regime, memorials have only been built at a much later time.[39]

"Austria – the Nazis' first victim" was a political slogan first used at the Moscow Conference in 1943 which went on to become the ideological basis for Austria and the national self-consciousness of Austrians during the periods of the allied occupation of 1945–1955 and the sovereign state of the Second Austrian Republic (1955–1980s[40][41][42]). The founders of the Second Austrian Republic interpreted this slogan to mean that the Anschluss in 1938 was an act of military aggression by Nazi Germany. Austrian statehood had been interrupted and therefore the newly revived Austria of 1945 could not and should not be responsible in any way for the Nazis' crimes. The "victim theory" formed by 1949 (German: Opferthese, Opferdoktrin) insisted that all the Austrians, including those who strongly supported Hitler, had been unwilling victims of a Nazi regime and therefore were not responsible for its crimes.

The "victim theory" became a fundamental myth of Austrian society. It made it possible for previously bitter political opponents – i.e. the social democrats and the conservative Catholics – to unite and to bring former Nazis back to the social and political life for the first time in Austrian history. For almost half a century, the Austrian state denied any continuity of the political regime of 1938–1945, actively kept up the self-sacrificing myth of Austrian nationhood, and cultivated a conservative spirit of national unity. Postwar denazification was quickly wound up; veterans of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS took an honorable place in society. The struggle for justice by the actual victims of Nazism – first of all Jews – were deprecated as an attempt to obtain illicit enrichment at the expense of the entire nation.

In 1986, the election of a former Wehrmacht intelligence officer, Kurt Waldheim, as a federal president put Austria on the verge of international isolation. Powerful outside pressure and an internal political discussion forced Austrians to reconsider their attitude to the past. Starting with the political administration of the 1990s and followed by most of the Austrian people by the mid-2000s, the nation admitted its collective responsibility for the crimes committed during the Nazi occupation and officially abandoned the "victim theory".

In 1984, in Lackenbach, almost 40 years after the end of war a memorial for the Zigeuner-AnhaltelagerRomani was unveiled. A memorial in Kemeten has not yet been started. Prior to the war, 200 Romani people lived in Kemeten. They were deported in 1941; only five of them came back in 1945.

Since 1992, there is the possibility of doing Zivildienst (alternative National Service) in the Austrian Holocaust Memorial Service. Approximately 15 people are deployed in the archive of the concentration camp memorial Mauthausen and alternatively in the camp itself. On 1 September 1992, the first Austrian Holocaust memorial serviceman started working in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Andreas Maislinger has taken over the idea from the Action Reconciliation Service for Peace. Annually approximately 30 civil servants are sent to Holocaust memorials and connected institutions in Europe, Israel, USA, South-America and China by the Holocaust Memorial Service.

At the Israeli Knesset in 1993, Austrian Chancellor Franz Vranitzky acknowledged the shared responsibility of Austrians for Nazi crimes.[43]

In mid-2004, the question of how to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the death of Robert Bernardis, who was shot on 8 August 1944 after being involved in the 20 July plot against Hitler, led to a political conflict. Politicians of the opposition (SPÖ, Grüne) as well as some celebrities suggested renaming a barracks as Robert Bernardis-Kaserne, which was turned down by the governing ÖVP and FPÖ. The defence minister Günther Platter (ÖVP) finally decided to build a memorial in the yard of the Towarek-Barrack in Enns. The Green Politician Terezija Stoisits pointed out that a barracks was named after Austrian sergeant Anton Schmid in Germany on 8 May 2004. Schmid was sentenced to death by a Wehrmacht court-martial and was shot on 13 April 1942, after he saved the lives of a hundred Jews in the Vilnius Ghetto.

The biggest Austrian Memorial for the remembrance of National Socialist crimes is the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. Part of the Contemporary History Museum Ebensee, it emerged through a private initiative in 2001 and remembers victims of the Ebensee concentration camp.

A study in 2019 by the Claims Conference showed that 56% of Austrians do not know that 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust and that 42% are unfamiliar with the Mauthausen concentration camp, located 146 kilometres (90 miles) from Vienna.[44]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In German: "Als Führer und Kanzler der deutschen Nation und des Reiches melde ich vor der deutschen Geschichte nunmehr den Eintritt meiner Heimat in das Deutsche Reich."

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Austria". encyclopedia.ushmm.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cymet, David (2012). History vs. Apologetics: The Holocaust, the Third Reich, and the Catholic Church. Lexington Books. pp. 113–114.

- ^ "Austria struggles to come to grips with Nazi past". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Austria post-1945 – Auschwitz".

- ^ Beniston, Judith (2003). "'Hitler's First Victim'? — Memory and Representation in Post-War Austria: Introduction". Austrian Studies. 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1353/aus.2003.0018. JSTOR 27944673. S2CID 160319529.

- ^ a b Steiner 1992, pp. S128–S133.

- ^ Whiteside 1962, p. 2.

- ^ Whiteside 1962, p. 1.

- ^ "Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Austria; Protocol, Declaration and Special Declaration [1920] ATS 3". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ Parkinson 1989, p. 74.

- ^ Scharf, Michaela (17 June 2014). "Austrian attempts to unite with Germany from the founding of the republic to the referendums in Tyrol and Salzburg in 1921". The First World War. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ 24. April 1921: Anschluss with Germany Direct Democracy (in German)

- ^ 29. Mai 1921: Anschluss with Germany Direct Democracy (in German)

- ^ "Kollerschlag". www.aeiou.at. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 296.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 45.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Bukey 2002, p. 34.

- ^ a b Gellately 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Gellately 2002, p. 108.

- ^ a b Gellately 2001, p. 222.

- ^ a b Gellately 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Gellately 2001, p. 216.

- ^ "Marko Feingold: "Ich bin fast jeden Tag traurig"". Kronen Zeitung. 3 June 2018.

- ^ Gottschlich, Maximilian (2012). Die große Abneigung. Wie antisemitisch ist Österreich? Kritische Befunde zu einer sozialen Krankheit (in German). Vienna.

- ^ Nasko, Siegfried; Reichl, Johannes (2000). Karl Renner. Zwischen Anschluß und Europa (in German). p. 273.

- ^ Rathkolb, Oliver (2005). Die paradoxe Republik. Österreich 1945 bis 2005 (in German). Vienna. p. 100. ISBN 3-5520-4967-3.

- ^ Zeillinger, Gerhard (23 December 2017). "Wiedergutmachung? – Das Wort kann ich schon nicht mehr hören!". Der Standard (in German).

- ^ Dvorak, Ludwig (29 March 2013). "Vom fragwürdigen Umgang mit "nützlichen" Zitaten". Der Standard (in German).

- ^ "Austria struggles to come to grips with Nazi past". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 November 2015.

- ^ Art 2006.

- ^ Konrad, Helmut (6 Nov 2008). "konrad.pdf" (PDF). doew.at. Retrieved 28 Aug 2022.

- ^ Boeckl-Klamper, Elisabeth; Mang, Thomas; Neugebauer, Wolfgang (2018). Gestapo-Leitstelle Wien 1938–1945 (in German). Vienna. pp. 299–305. ISBN 978-3-9024-9483-2.

- ^ Schafranek, Hans (2017). Widerstand und Verrat: Gestapospitzel im antifaschistischen Untergrund (in German). Vienna. pp. 161–248. ISBN 978-3-7076-0622-5.

- ^ Molden, Fritz (1988). Die Feuer in der Nacht. Opfer und Sinn des österreichischen Widerstandes 1938–1945 (in German). Vienna. p. 122.

- ^ Broucek, Peter (2008). Die österreichische Identität im Widerstand 1938–1945 (in German). p. 163.

- ^ Stehle, Hansjakob (5 January 1996). "Die Spione aus dem Pfarrhaus" [The spy from the rectory]. Die Zeit (in German).

- ^ "Austria unveils Holocaust memorial that remembers 64,440 murdered Austrian Jews". ABC News. November 9, 2021. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2025.

- ^ Uhl 1997, p. 66.

- ^ Art 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 16.

- ^ "Austria post-1945 – Auschwitz".

- ^ Schwartz, Yaakov (May 2, 2019). "Most Austrians don't know 6 million Jews were killed in Holocaust, survey finds". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2025.

Sources

[edit]- Art, David (2005). The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1394-4883-3.

- Art, David (2006). The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-5683-6.

- Bukey, Evan Burr (2002). Hitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945. University North Carolina. ISBN 0-8078-5363-1.

- Embacher, H.; Ecker, M. (2010). "A Nation of Victims". The Politics of War Trauma: The Aftermath of World War II in Eleven European Countries. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 15–48. ISBN 978-9-0526-0371-1.

- Gellately, Robert (2002). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1928-0291-7.

- Gellately, Robert (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-6910-8684-2.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. Penguin. ISBN 0-1402-7239-9.

- Parkinson, F. (1989). Conquering the Past: Austrian Nazism Yesterday and Today. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2055-4.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-6717-2868-7.

- Steiner, Herbert (1992). "The Role of the Resistance in Austria, with Special Reference to the Labor Movement". The Journal of Modern History. 64: S128 – S133. doi:10.1086/244432. JSTOR 2124973. S2CID 145445683.

- Uhl, Heidemarie (1997). "Austria's Perception of the Second World War and the National Socialist Period". Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transactionpublishers. pp. 64–94. ISBN 978-1-4128-1769-1.

- Whiteside, Andrew Gladding (1962). Austrian National Socialism Before 1918. Springer.

Further reading

[edit]- Pauley, Bruce F. (2000). From Prejudice to Persecution: A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6376-3.

- Steininger, Wolf (2008). Austria, Germany, and the Cold War: from the Anschluss to the State Treaty 1938–1955. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-8454-5326-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

.svg/250px-Flag_of_Germany_(1935–1945).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_Germany_(1935–1945).svg.png)