Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bipedalism

View on Wikipedia

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped /ˈbaɪpɛd/, meaning 'two feet' (from Latin bis 'double' and pes 'foot'). Types of bipedal movement include walking or running (a bipedal gait) and hopping.

Several groups of modern species are habitual bipeds whose normal method of locomotion is two-legged. In the Triassic period some groups of archosaurs, a group that includes crocodiles and dinosaurs, developed bipedalism; among the dinosaurs, all the early forms and many later groups were habitual or exclusive bipeds; the birds are members of a clade of exclusively bipedal dinosaurs, the theropods. Within mammals, habitual bipedalism has evolved multiple times, with the macropods, kangaroo rats and mice, springhare,[4] hopping mice, pangolins and hominin apes, australopithecines, including humans) as well as many other extinct groups evolving the trait independently.

A larger number of modern species intermittently or briefly use a bipedal gait. Several lizard species move bipedally when running, usually to escape from threats.[5] Many primate and bear species will adopt a bipedal gait in order to reach food or explore their environment, though there are a few cases where they walk on their hind limbs only. Several arboreal primate species, such as gibbons and indriids, exclusively walk on two legs during the brief periods they spend on the ground. Many animals rear up on their hind legs while fighting or copulating. Some animals commonly stand on their hind legs to reach food, keep watch, threaten a competitor or predator, or pose in courtship, but do not move bipedally.

Etymology

[edit]The word is derived from the Latin words bi(s) 'two' and ped- 'foot', as contrasted with quadruped 'four feet'.

Advantages

[edit]Limited and exclusive bipedalism can offer a species several advantages. Bipedalism raises the head; this allows a greater field of vision with improved detection of distant dangers or resources, access to deeper water for wading animals and allows the animals to reach higher food sources with their mouths. While upright, non-locomotory limbs become free for other uses, including manipulation (in primates and rodents), flight (in birds), digging (in the giant pangolin), combat (in bears, great apes and the large monitor lizard) or camouflage.

The maximum bipedal speed appears slower than the maximum speed of quadrupedal movement with a flexible backbone – both the ostrich and the red kangaroo can reach speeds of 70 km/h (43 mph), while the cheetah can exceed 100 km/h (62 mph).[6][7] Even though bipedalism is slower at first, over long distances, it has allowed humans to outrun most other animals according to the endurance running hypothesis.[8] Bipedality in kangaroo rats has been hypothesized to improve locomotor performance, [clarification needed] which could aid in escaping from predators.[9][10]

Facultative and obligate bipedalism

[edit]Zoologists often label behaviors, including bipedalism, as "facultative" (i.e. optional) or "obligate" (the animal has no reasonable alternative). Even this distinction is not completely clear-cut — for example, humans other than infants normally walk and run in biped fashion, but almost all can crawl on hands and knees when necessary. There are even reports of humans who normally walk on all fours with their feet but not their knees on the ground, but these cases are a result of conditions such as Uner Tan syndrome — very rare genetic neurological disorders rather than normal behavior.[11] Even if one ignores exceptions caused by some kind of injury or illness, there are many unclear cases, including the fact that "normal" humans can crawl on hands and knees. This article therefore avoids the terms "facultative" and "obligate", and focuses on the range of styles of locomotion normally used by various groups of animals. Normal humans may be considered "obligate" bipeds because the alternatives are very uncomfortable and usually only resorted to when walking is impossible.

Movement

[edit]There are a number of states of movement commonly associated with bipedalism.

- Standing. Staying still on both legs. In most bipeds this is an active process, requiring constant adjustment of balance.

- Walking. One foot in front of another, with at least one foot on the ground at any time.

- Running. One foot in front of another, with periods where both feet are off the ground.

- Jumping/hopping. Moving by a series of jumps with both feet moving together.

- Skipping. A form of bipedal locomotion that combines the step and hop.

Bipedal animals

[edit]The great majority of living terrestrial vertebrates are quadrupeds, with bipedalism exhibited by only a handful of living groups. Humans, gibbons and large birds walk by raising one foot at a time. On the other hand, most macropods, smaller birds, lemurs and bipedal rodents move by hopping on both legs simultaneously. Tree kangaroos are able to walk or hop, most commonly alternating feet when moving arboreally and hopping on both feet simultaneously when on the ground.

Extant reptiles

[edit]Many species of lizards become bipedal during high-speed, sprint locomotion,[5] including the world's fastest lizard, the spiny-tailed iguana (genus Ctenosaura).

Early reptiles and lizards

[edit]The first known biped is the bolosaurid Eudibamus whose fossils date from 290 million years ago.[12][13] Its long hind-legs, short forelegs, and distinctive joints all suggest bipedalism. The species became extinct in the early Permian.

Archosaurs (includes crocodilians and dinosaurs)

[edit]Birds

[edit]All birds are bipeds, as is the case for all theropod dinosaurs. However, hoatzin chicks have claws on their wings which they use for climbing.

Other archosaurs

[edit]Bipedalism evolved more than once in archosaurs, the group that includes both dinosaurs and crocodilians.[14] All dinosaurs are thought to be descended from a fully bipedal ancestor, perhaps similar to Eoraptor.

Dinosaurs diverged from their archosaur ancestors approximately 230 million years ago during the Middle to Late Triassic period, roughly 20 million years after the Permian-Triassic extinction event wiped out an estimated 95 percent of all life on Earth.[15][16] Radiometric dating of fossils from the early dinosaur genus Eoraptor establishes its presence in the fossil record at this time. Paleontologists suspect Eoraptor resembles the common ancestor of all dinosaurs;[17] if this is true, its traits suggest that the first dinosaurs were small, bipedal predators.[18] The discovery of primitive, dinosaur-like ornithodirans such as Marasuchus and Lagerpeton in Argentinian Middle Triassic strata supports this view; analysis of recovered fossils suggests that these animals were indeed small, bipedal predators.

Bipedal movement also re-evolved in a number of other dinosaur lineages such as the iguanodonts. Some extinct members of Pseudosuchia, a sister group to the avemetatarsalians (the group including dinosaurs and relatives), also evolved bipedal forms – a poposauroid from the Triassic, Effigia okeeffeae, is thought to have been bipedal.[19] Pterosaurs were previously thought to have been bipedal, but recent trackways have all shown quadrupedal locomotion.

Mammals

[edit]A number of groups of extant mammals have independently evolved bipedalism as their main form of locomotion – for example, humans, ground pangolins, the extinct giant ground sloths, numerous species of jumping rodents and macropods. Humans, as their bipedalism has been extensively studied, are documented in the next section. Macropods are believed to have evolved bipedal hopping only once in their evolution, at some time no later than 45 million years ago.[20]

Bipedal movement is less common among mammals, most of which are quadrupedal. All primates possess some bipedal ability, though most species primarily use quadrupedal locomotion on land. Primates aside, the macropods (kangaroos, wallabies and their relatives), kangaroo rats and mice, hopping mice and springhare move bipedally by hopping. Very few non-primate mammals commonly move bipedally with an alternating leg gait. Exceptions are the ground pangolin and in some circumstances the tree kangaroo.[21] One black bear, Pedals, became famous locally and on the internet for having a frequent bipedal gait, although this is attributed to injuries on the bear's front paws. A two-legged fox was filmed in a Derbyshire garden in 2023, most likely having been born that way.[22]

Primates

[edit]

Most bipedal animals move with their backs close to horizontal, using a long tail to balance the weight of their bodies. The primate version of bipedalism is unusual because the back is close to upright (completely upright in humans), and the tail may be absent entirely. Many primates can stand upright on their hind legs without any support. Chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, gibbons[23] and baboons[24] exhibit forms of bipedalism. On the ground sifakas move like all indrids with bipedal sideways hopping movements of the hind legs, holding their forelimbs up for balance.[25] Geladas, although usually quadrupedal, will sometimes move between adjacent feeding patches with a squatting, shuffling bipedal form of locomotion.[26] However, they can only do so for brief amounts, as their bodies are not adapted for constant bipedal locomotion.

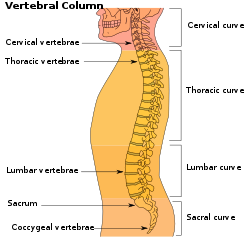

Humans are the only primates who are normally biped, due to an extra curve in the spine (i.e. the lumbar lordosis) which shifts the center of gravity more dorsally and thus stabilizes the upright position, as well as shorter arms relative to the legs than is the case for the nonhuman great apes. The evolution of human bipedalism began in primates about four million years ago,[27] or as early as seven million years ago with Sahelanthropus[28][29] or about 12 million years ago with Danuvius guggenmosi. One hypothesis for human bipedalism is that it evolved as a result of differentially successful survival from carrying food to share with group members,[30] although there are alternative hypotheses.

- Injured individuals

Injured chimpanzees and bonobos have been capable of sustained bipedalism.[31]

Three captive primates, one macaque Natasha[32] and two chimps, Oliver and Poko[33] (chimpanzee), were found to move bipedally. Natasha switched to exclusive bipedalism after an illness, while Poko was discovered in captivity in a tall, narrow cage.[34][35] Oliver reverted to knuckle-walking after developing arthritis. Non-human primates often use bipedal locomotion when carrying food, or while moving through shallow water.

Limited bipedalism

[edit]Limited bipedalism in mammals

[edit]Other mammals engage in limited, non-locomotory, bipedalism. A number of other animals, such as rats, raccoons, and beavers will squat on their hindlegs to manipulate some objects but revert to four limbs when moving (the beaver will move bipedally if transporting wood for their dams, as will the raccoon when holding food). Bears will fight in a bipedal stance to use their forelegs as weapons. A number of mammals will adopt a bipedal stance in specific situations such as for feeding or fighting. Ground squirrels and meerkats will stand on hind legs to survey their surroundings, but will not walk bipedally. Dogs (e.g. Faith) can stand or move on two legs if trained, or if birth defect or injury precludes quadrupedalism. The gerenuk antelope stands on its hind legs while eating from trees, as did the extinct giant ground sloth and chalicotheres. The spotted skunk will walk on its front legs when threatened, rearing up on its front legs while facing the attacker so that its anal glands, capable of spraying an offensive oil, face its attacker.

Limited bipedalism in non-mammals (and non-birds)

[edit]Bipedalism is unknown among the amphibians. Among the non-archosaur reptiles bipedalism is rare, but it is found in the "reared-up" running of lizards such as agamids and monitor lizards.[5] Many reptile species will also temporarily adopt bipedalism while fighting.[36] One genus of basilisk lizard can run bipedally across the surface of water for some distance. Among arthropods, cockroaches are known to move bipedally at high speeds.[37] Bipedalism is rarely found outside terrestrial animals, though at least two species of octopus walk bipedally on the sea floor using two of their arms, allowing the remaining arms to be used to camouflage the octopus as a mat of algae or a floating coconut.[38]

Evolution of human bipedalism

[edit]−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are at least twelve distinct hypotheses as to how and why bipedalism evolved in humans, and also some debate as to when. Bipedalism evolved well before the large human brain or the development of stone tools.[39] Bipedal specializations are found in Australopithecus fossils from 4.2 to 3.9 million years ago and recent studies have suggested that obligate bipedal hominid species were present as early as 7 million years ago.[28][40] Nonetheless, the evolution of bipedalism was accompanied by significant evolutions in the spine including the forward movement in position of the foramen magnum, where the spinal cord leaves the cranium.[41] Recent evidence regarding modern human sexual dimorphism (physical differences between male and female) in the lumbar spine has been seen in pre-modern primates such as Australopithecus africanus. This dimorphism has been seen as an evolutionary adaptation of females to bear lumbar load better during pregnancy, an adaptation that non-bipedal primates would not need to make.[42][43] Adapting bipedalism would have required less shoulder stability, which allowed the shoulder and other limbs to become more independent of each other and adapt for specific suspensory behaviors. In addition to the change in shoulder stability, changing locomotion would have increased the demand for shoulder mobility, which would have propelled the evolution of bipedalism forward.[44] The different hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive and a number of selective forces may have acted together to lead to human bipedalism. It is important to distinguish between adaptations for bipedalism and adaptations for running, which came later still.

The form and function of modern-day humans' upper bodies appear to have evolved from living in a more forested setting. Living in this kind of environment would have made it so that being able to travel arboreally would have been advantageous at the time. Although different to human walking, bipedal locomotion in trees was thought to be advantageous.[45] It has also been proposed that, like some modern-day apes, early hominins had undergone a knuckle-walking stage prior to adapting the back limbs for bipedality while retaining forearms capable of grasping.[46] Numerous causes for the evolution of human bipedalism involve freeing the hands for carrying and using tools, sexual dimorphism in provisioning, changes in climate and environment (from jungle to savanna) that favored a more elevated eye-position, and to reduce the amount of skin exposed to the tropical sun.[47] It is possible that bipedalism provided a variety of benefits to the hominin species, and scientists have suggested multiple reasons for evolution of human bipedalism.[48] There is also not only the question of why the earliest hominins were partially bipedal but also why hominins became more bipedal over time. For example, the postural feeding hypothesis describes how the earliest hominins became bipedal for the benefit of reaching food in trees while the savanna-based theory describes how the late hominins that started to settle on the ground became increasingly bipedal.[49]

Multiple factors

[edit]Napier (1963) argued that it is unlikely that a single factor drove the evolution of bipedalism. He stated "It seems unlikely that any single factor was responsible for such a dramatic change in behaviour. In addition to the advantages of accruing from ability to carry objects – food or otherwise – the improvement of the visual range and the freeing of the hands for purposes of defence and offence may equally have played their part as catalysts."[50] Sigmon (1971) demonstrated that chimpanzees exhibit bipedalism in different contexts, and one single factor should be used to explain bipedalism: preadaptation for human bipedalism.[51] Day (1986) emphasized three major pressures that drove evolution of bipedalism: food acquisition, predator avoidance, and reproductive success.[52] Ko (2015) stated that there are two main questions regarding bipedalism 1. Why were the earliest hominins partially bipedal? and 2. Why did hominins become more bipedal over time? He argued that these questions can be answered with combination of prominent theories such as Savanna-based, Postural feeding, and Provisioning.[53]

Savannah-based theory

[edit]According to the Savanna-based theory, hominines came down from the tree's branches and adapted to life on the savanna by walking erect on two feet. The theory suggests that early hominids were forced to adapt to bipedal locomotion on the open savanna after they left the trees. One of the proposed mechanisms was the knuckle-walking hypothesis, which states that human ancestors used quadrupedal locomotion on the savanna, as evidenced by morphological characteristics found in Australopithecus anamensis and Australopithecus afarensis forelimbs, and that it is less parsimonious to assume that knuckle walking developed twice in genera Pan and Gorilla instead of evolving it once as synapomorphy for Pan and Gorilla before losing it in Australopithecus.[54] The evolution of an orthograde posture would have been very helpful on a savanna as it would allow the ability to look over tall grasses in order to watch out for predators, or terrestrially hunt and sneak up on prey.[55] It was also suggested in P. E. Wheeler's "The evolution of bipedality and loss of functional body hair in hominids", that a possible advantage of bipedalism in the savanna was reducing the amount of surface area of the body exposed to the sun, helping regulate body temperature.[56] In fact, Elizabeth Vrba's turnover pulse hypothesis supports the savanna-based theory by explaining the shrinking of forested areas due to global warming and cooling, which forced animals out into the open grasslands and caused the need for hominids to acquire bipedality.[57]

Others state hominines had already achieved the bipedal adaptation that was used in the savanna. The fossil evidence reveals that early bipedal hominins were still adapted to climbing trees at the time they were also walking upright.[58] It is possible that bipedalism evolved in the trees, and was later applied to the savanna as a vestigial trait. Humans and orangutans are both unique to a bipedal reactive adaptation when climbing on thin branches, in which they have increased hip and knee extension in relation to the diameter of the branch, which can increase an arboreal feeding range and can be attributed to a convergent evolution of bipedalism evolving in arboreal environments.[59] Hominine fossils found in dry grassland environments led anthropologists to believe hominines lived, slept, walked upright, and died only in those environments because no hominine fossils were found in forested areas. However, fossilization is a rare occurrence—the conditions must be just right in order for an organism that dies to become fossilized for somebody to find later, which is also a rare occurrence. The fact that no hominine fossils were found in forests does not ultimately lead to the conclusion that no hominines ever died there. The convenience of the savanna-based theory caused this point to be overlooked for over a hundred years.[57]

Some of the fossils found actually showed that there was still an adaptation to arboreal life. For example, Lucy, the famous Australopithecus afarensis, found in Hadar in Ethiopia, which may have been forested at the time of Lucy's death, had curved fingers that would still give her the ability to grasp tree branches, but she walked bipedally. "Little Foot", a nearly-complete specimen of Australopithecus africanus, has a divergent big toe as well as the ankle strength to walk upright. "Little Foot" could grasp things using his feet like an ape, perhaps tree branches, and he was bipedal. Ancient pollen found in the soil in the locations in which these fossils were found suggest that the area used to be much more wet and covered in thick vegetation and has only recently become the arid desert it is now.[57]

Traveling efficiency hypothesis

[edit]An alternative explanation is that the mixture of savanna and scattered forests increased terrestrial travel by proto-humans between clusters of trees, and bipedalism offered greater efficiency for long-distance travel between these clusters than quadrupedalism.[60][61] In an experiment monitoring chimpanzee metabolic rate via oxygen consumption, it was found that the quadrupedal and bipedal energy costs were very similar, implying that this transition in early ape-like ancestors would not have been very difficult or energetically costing.[62] This increased travel efficiency is likely to have been selected for as it assisted foraging across widely dispersed resources.

Postural feeding hypothesis

[edit]The postural feeding hypothesis has been recently supported by Dr. Kevin Hunt, a professor at Indiana University.[63] This hypothesis asserts that chimpanzees were only bipedal when they eat. While on the ground, they would reach up for fruit hanging from small trees and while in trees, bipedalism was used to reach up to grab for an overhead branch. These bipedal movements may have evolved into regular habits because they were so convenient in obtaining food. Also, Hunt's hypotheses states that these movements coevolved with chimpanzee arm-hanging, as this movement was very effective and efficient in harvesting food. When analyzing fossil anatomy, Australopithecus afarensis has very similar features of the hand and shoulder to the chimpanzee, which indicates hanging arms. Also, the Australopithecus hip and hind limb very clearly indicate bipedalism, but these fossils also indicate very inefficient locomotive movement when compared to humans. For this reason, Hunt argues that bipedalism evolved more as a terrestrial feeding posture than as a walking posture.[63]

A related study conducted by University of Birmingham, Professor Susannah Thorpe examined the most arboreal great ape, the orangutan, holding onto supporting branches in order to navigate branches that were too flexible or unstable otherwise. In more than 75 percent of observations, the orangutans used their forelimbs to stabilize themselves while navigating thinner branches. Increased fragmentation of forests where A. afarensis as well as other ancestors of modern humans and other apes resided could have contributed to this increase of bipedalism in order to navigate the diminishing forests. Findings also could shed light on discrepancies observed in the anatomy of A. afarensis, such as the ankle joint, which allowed it to "wobble" and long, highly flexible forelimbs. If bipedalism started from upright navigation in trees, it could explain both increased flexibility in the ankle as well as long forelimbs which grab hold of branches.[64][65][66][67][68][69]

Provisioning model

[edit]One theory on the origin of bipedalism is the behavioral model presented by C. Owen Lovejoy, known as "male provisioning".[70] Lovejoy theorizes that the evolution of bipedalism was linked to monogamy. In the face of long inter-birth intervals and low reproductive rates typical of the apes, early hominids engaged in pair-bonding that enabled greater parental effort directed towards rearing offspring. Lovejoy proposes that male provisioning of food would improve the offspring survivorship and increase the pair's reproductive rate. Thus the male would leave his mate and offspring to search for food and return carrying the food in his arms walking on his legs. This model is supported by the reduction ("feminization") of the male canine teeth in early hominids such as Sahelanthropus tchadensis[71] and Ardipithecus ramidus,[72] which along with low body size dimorphism in Ardipithecus[73] and Australopithecus,[74][75][76] suggests a reduction in inter-male antagonistic behavior in early hominids.[77] In addition, this model is supported by a number of modern human traits associated with concealed ovulation (permanently enlarged breasts, lack of sexual swelling) and low sperm competition (moderate sized testes, low sperm mid-piece volume) that argues against recent adaptation to a polygynous reproductive system.[77]

However, this model has been debated, as others have argued that early bipedal hominids were instead polygynous. Among most monogamous primates, males and females are about the same size. That is sexual dimorphism is minimal, and other studies have suggested that Australopithecus afarensis males were nearly twice the weight of females. However, Lovejoy's model posits that the larger range a provisioning male would have to cover (to avoid competing with the female for resources she could attain herself) would select for increased male body size to limit predation risk.[78] Furthermore, as the species became more bipedal, specialized feet would prevent the infant from conveniently clinging to the mother – hampering the mother's freedom[79] and thus make her and her offspring more dependent on resources collected by others. Modern monogamous primates such as gibbons tend to be also territorial, but fossil evidence indicates that Australopithecus afarensis lived in large groups. However, while both gibbons and hominids have reduced canine sexual dimorphism, female gibbons enlarge ('masculinize') their canines so they can actively share in the defense of their home territory. Instead, the reduction of the male hominid canine is consistent with reduced inter-male aggression in a pair-bonded though group living primate.

Early bipedalism in homininae model

[edit]Recent studies of 4.4 million years old Ardipithecus ramidus suggest bipedalism. It is thus possible that bipedalism evolved very early in homininae and was reduced in chimpanzee and gorilla when they became more specialized. Other recent studies of the foot structure of Ardipithecus ramidus suggest that the species was closely related to African-ape ancestors. This possibly provides a species close to the true connection between fully bipedal hominins and quadruped apes.[80] According to Richard Dawkins in his book "The Ancestor's Tale", chimps and bonobos are descended from Australopithecus gracile type species while gorillas are descended from Paranthropus. These apes may have once been bipedal, but then lost this ability when they were forced back into an arboreal habitat, presumably by those australopithecines from whom eventually evolved hominins. Early hominines such as Ardipithecus ramidus may have possessed an arboreal type of bipedalism that later independently evolved towards knuckle-walking in chimpanzees and gorillas[81] and towards efficient walking and running in modern humans (see figure). It is also proposed that one cause of Neanderthal extinction was a less efficient running.

Warning display (aposematic) model

[edit]Joseph Jordania from the University of Melbourne recently (2011) suggested that bipedalism was one of the central elements of the general defense strategy of early hominids, based on aposematism, or warning display and intimidation of potential predators and competitors with exaggerated visual and audio signals. According to this model, hominids were trying to stay as visible and as loud as possible all the time. Several morphological and behavioral developments were employed to achieve this goal: upright bipedal posture, longer legs, long tightly coiled hair on the top of the head, body painting, threatening synchronous body movements, loud voice and extremely loud rhythmic singing/stomping/drumming on external subjects.[82] Slow locomotion and strong body odor (both characteristic for hominids and humans) are other features often employed by aposematic species to advertise their non-profitability for potential predators.

Other behavioural models

[edit]There are a variety of ideas which promote a specific change in behaviour as the key driver for the evolution of hominid bipedalism. For example, Wescott (1967) and later Jablonski & Chaplin (1993) suggest that bipedal threat displays could have been the transitional behaviour which led to some groups of apes beginning to adopt bipedal postures more often. Others (e.g. Dart 1925) have offered the idea that the need for more vigilance against predators could have provided the initial motivation. Dawkins (e.g. 2004) has argued that it could have begun as a kind of fashion that just caught on and then escalated through sexual selection. And it has even been suggested (e.g. Tanner 1981:165) that male phallic display could have been the initial incentive, as well as increased sexual signaling in upright female posture.[55]

Thermoregulatory model

[edit]The thermoregulatory model explaining the origin of bipedalism is one of the simplest theories so far advanced, but it is a viable explanation. Dr. Peter Wheeler, a professor of evolutionary biology, proposes that bipedalism raises the amount of body surface area higher above the ground which results in a reduction in heat gain and helps heat dissipation.[83][84][85] When a hominid is higher above the ground, the organism accesses more favorable wind speeds and temperatures. During heat seasons, greater wind flow results in a higher heat loss, which makes the organism more comfortable. Also, Wheeler explains that a vertical posture minimizes the direct exposure to the sun whereas quadrupedalism exposes more of the body to direct exposure. Analysis and interpretations of Ardipithecus reveal that this hypothesis needs modification to consider that the forest and woodland environmental preadaptation of early-stage hominid bipedalism preceded further refinement of bipedalism by the pressure of natural selection. This then allowed for the more efficient exploitation of the hotter conditions ecological niche, rather than the hotter conditions being hypothetically bipedalism's initial stimulus. A feedback mechanism from the advantages of bipedality in hot and open habitats would then in turn make a forest preadaptation solidify as a permanent state.[86]

Carrying models

[edit]Charles Darwin wrote that "Man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands, which are so admirably adapted to the act of obedience of his will". Darwin (1871:52) and many models on bipedal origins are based on this line of thought. Gordon Hewes (1961) suggested that the carrying of meat "over considerable distances" (Hewes 1961:689) was the key factor. Isaac (1978) and Sinclair et al. (1986) offered modifications of this idea, as indeed did Lovejoy (1981) with his "provisioning model" described above. Others, such as Nancy Tanner (1981), have suggested that infant carrying was key, while others again have suggested stone tools and weapons drove the change.[87] This stone-tools theory is very unlikely, as though ancient humans were known to hunt, the discovery of tools was not discovered for thousands of years after the origin of bipedalism, chronologically precluding it from being a driving force of evolution. (Wooden tools and spears fossilize poorly and therefore it is difficult to make a judgment about their potential usage.)

Wading models

[edit]The observation that large primates, including especially the great apes, that predominantly move quadrupedally on dry land, tend to switch to bipedal locomotion in waist deep water, has led to the idea that the origin of human bipedalism may have been influenced by waterside environments. This idea, labelled "the wading hypothesis",[88] was originally suggested by the Oxford marine biologist Alister Hardy who said: "It seems to me likely that Man learnt to stand erect first in water and then, as his balance improved, he found he became better equipped for standing up on the shore when he came out, and indeed also for running."[89] It was then promoted by Elaine Morgan, as part of the aquatic ape hypothesis, who cited bipedalism among a cluster of other human traits unique among primates, including voluntary control of breathing, hairlessness and subcutaneous fat.[90] The "aquatic ape hypothesis", as originally formulated, has not been accepted or considered a serious theory within the anthropological scholarly community.[91] Others, however, have sought to promote wading as a factor in the origin of human bipedalism without referring to further ("aquatic ape" related) factors. Since 2000 Carsten Niemitz has published a series of papers and a book[92] on a variant of the wading hypothesis, which he calls the "amphibian generalist theory" (German: Amphibische Generalistentheorie).

Other theories have been proposed that suggest wading and the exploitation of aquatic food sources (providing essential nutrients for human brain evolution[93] or critical fallback foods[94]) may have exerted evolutionary pressures on human ancestors promoting adaptations which later assisted full-time bipedalism. It has also been thought that consistent water-based food sources had developed early hominid dependency and facilitated dispersal along seas and rivers.[95]

Vocal learning model

[edit]An essay[96] by Albert Roca suggests that bipedalism was adopted as a consequence of the acquisition of vocal learning in the human lineage, which led to a longer brain development period, which led to an increased altriciality at birth, which positively selected the offspring of the more efficient bipedal females, thus allowing the extrauterine increase of the brain size and ultimately the development of language. The study highlights the fact that all species with vocal learning exhibit peculiar locomotor adaptations.

Consequences

[edit]Prehistoric fossil records show that early hominins first developed bipedalism before being followed by an increase in brain size.[97] The consequences of these two changes in particular resulted in painful and difficult labor due to the increased favor of a narrow pelvis for bipedalism being countered by larger heads passing through the constricted birth canal. This phenomenon is commonly known as the obstetrical dilemma.

Non-human primates habitually deliver their young on their own, but the same cannot be said for modern-day humans. Isolated birth appears to be rare and actively avoided cross-culturally, even if birthing methods may differ between said cultures. This is due to the fact that the narrowing of the hips and the change in the pelvic angle caused a discrepancy in the ratio of the size of the head to the birth canal. The result of this is that there is greater difficulty in birthing for hominins in general, let alone to be doing it by oneself.[98]

Physiology

[edit]Bipedal movement occurs in a number of ways and requires many mechanical and neurological adaptations. Some of these are described below.

Biomechanics

[edit]Standing

[edit]Energy-efficient means of standing bipedally involve constant adjustment of balance, and of course these must avoid overcorrection. The difficulties associated with simple standing in upright humans are highlighted by the greatly increased risk of falling present in the elderly, even with minimal reductions in control system effectiveness.

Shoulder stability

[edit]Shoulder stability would decrease with the evolution of bipedalism. Shoulder mobility would increase because the need for a stable shoulder is only present in arboreal habitats. Shoulder mobility would support suspensory locomotion behaviors which are present in human bipedalism. The forelimbs are freed from weight-bearing requirements, which makes the shoulder a place of evidence for the evolution of bipedalism.[99]

Walking

[edit]

Unlike non-human apes that are able to practice bipedality such as Pan and Gorilla, hominins have the ability to move bipedally without the utilization of a bent-hip-bent-knee (BHBK) gait, which requires the engagement of both the hip and the knee joints. This human ability to walk is made possible by the spinal curvature humans have that non-human apes do not.[100] Rather, walking is characterized by an "inverted pendulum" movement in which the center of gravity vaults over a stiff leg with each step.[101] Force plates can be used to quantify the whole-body kinetic & potential energy, with walking displaying an out-of-phase relationship indicating exchange between the two.[101] This model applies to all walking organisms regardless of the number of legs, and thus bipedal locomotion does not differ in terms of whole-body kinetics.[102]

In humans, walking is composed of several separate processes:[101]

- Vaulting over a stiff stance leg

- Passive ballistic movement of the swing leg

- A short 'push' from the ankle prior to toe-off, propelling the swing leg

- Rotation of the hips about the axis of the spine, to increase stride length

- Rotation of the hips about the horizontal axis to improve balance during stance

Running

[edit]

Early hominins underwent post-cranial changes in order to better adapt to bipedality, especially running. One of these changes is having longer hindlimbs proportional to the forelimbs and their effects. As previously mentioned, longer hindlimbs assist in thermoregulation by reducing the total surface area exposed to direct sunlight while simultaneously allowing for more space for cooling winds. Additionally, having longer limbs is more energy-efficient, since longer limbs mean that overall muscle strain is lessened. Better energy efficiency, in turn, means higher endurance, particularly when running long distances.[103]

Running is characterized by a spring-mass movement.[101] Kinetic and potential energy are in phase, and the energy is stored & released from a spring-like limb during foot contact,[101] achieved by the plantar arch and the Achilles tendon in the foot and leg, respectively.[103] Again, the whole-body kinetics are similar to animals with more limbs.[102]

Musculature

[edit]Bipedalism requires strong leg muscles, particularly in the thighs. Contrast in domesticated poultry the well muscled legs, against the small and bony wings. Likewise in humans, the quadriceps and hamstring muscles of the thigh are both so crucial to bipedal activities that each alone is much larger than the well-developed biceps of the arms. In addition to the leg muscles, the increased size of the gluteus maximus in humans is an important adaptation as it provides support and stability to the trunk and lessens the amount of stress on the joints when running.[103]

Respiration

[edit]

Quadrupeds, have more restrictive breathing respire while moving than do bipedal humans.[104] "Quadrupedal species normally synchronize the locomotor and respiratory cycles at a constant ratio of 1:1 (strides per breath) in both the trot and gallop. Human runners differ from quadrupeds in that while running they employ several phase-locked patterns (4:1, 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, 5:2, and 3:2), although a 2:1 coupling ratio appears to be favored. Even though the evolution of bipedal gait has reduced the mechanical constraints on respiration in man, thereby permitting greater flexibility in breathing pattern, it has seemingly not eliminated the need for the synchronization of respiration and body motion during sustained running."[105]

Respiration through bipedality means that there is better breath control in bipeds, which can be associated with brain growth. The modern brain utilizes approximately 20% of energy input gained through breathing and eating, as opposed to species like chimpanzees who use up twice as much energy as humans for the same amount of movement. This excess energy, leading to brain growth, also leads to the development of verbal communication. This is because breath control means that the muscles associated with breathing can be manipulated into creating sounds. This means that the onset of bipedality, leading to more efficient breathing, may be related to the origin of verbal language.[104]

Bipedal robots

[edit]

For nearly the whole of the 20th century, bipedal robots were very difficult to construct and robot locomotion involved only wheels, treads, or multiple legs. Recent cheap and compact computing power has made two-legged robots more feasible. Some notable biped robots are ASIMO, HUBO, MABEL and QRIO. Recently, spurred by the success of creating a fully passive, un-powered bipedal walking robot,[106] those working on such machines have begun using principles gleaned from the study of human and animal locomotion, which often relies on passive mechanisms to minimize power consumption.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The red kangaroo can attain a similar speed for short distances.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Stewart, D. (2006-08-01). "A Bird Like No Other". National Wildlife. National Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 99–101. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- ^ Penny, M. (2002). The Secret World of Kangaroos. Austin, TX: Raintree Steck-Vaughn. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7398-4986-6.

- ^ Heglund, NC; Cavagna, GA; Taylor, CR (1982). "Energetics and mechanics of terrestrial locomotion. III. Energy changes of the centre of mass as a function of speed and body size in birds and mammals". Journal of Experimental Biology. 97 (1): 41–56. Bibcode:1982JExpB..97...41H. doi:10.1242/jeb.97.1.41. PMID 7086349.

- ^ a b c Clemente, Christofer J.; Wu, Nicholas C. (2018). "Body and tail-assisted pitch control facilitates bipedal locomotion in Australian agamid lizards". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 15 (146) 20180276. doi:10.1098/rsif.2018.0276. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 6170770. PMID 30257922.

- ^ Garland, T. Jr. (1983). "The relation between maximal running speed and body mass in terrestrial mammals" (PDF). Journal of Zoology, London. 199 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1983.tb02087.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ Sharp, N.C.C. (1997). "Timed running speed of a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus)". Journal of Zoology. 241 (3): 493–494. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb04840.x.

- ^ Bramble, Dennis M.; Lieberman, Daniel E. (2004-11-18). "Endurance running and the evolution of Homo" (PDF). Nature. 432 (7015): 345–352. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..345B. doi:10.1038/nature03052. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15549097. S2CID 2470602.

- ^ Djawdan, M (1993). "Locomotor performance of bipedal and quadrupedal heteromyid rodents". Functional Ecology. 7 (2): 195–202. Bibcode:1993FuEco...7..195D. doi:10.2307/2389887. JSTOR 2389887.

- ^ Djawdan, M.; Garland, T. Jr. (1988). "Maximal running speeds of bipedal and quadrupedal rodents" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 69 (4): 765–772. doi:10.2307/1381631. JSTOR 1381631. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-06-16.

- ^ Humphrey, N.; Skoyles, J.R.; Keynes, R. (2005). "Human Hand-Walkers: Five Siblings Who Never Stood Up" (PDF). Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science, London School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-10.

- ^ "Upright lizard leaves dinosaur standing". cnn.com. 2000-11-03. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Berman, David S.; et al. (2000). "Early Permian Bipedal Reptile". Science. 290 (5493): 969–972. Bibcode:2000Sci...290..969B. doi:10.1126/science.290.5493.969. PMID 11062126.

- ^ Hutchinson, J. R. (2006). "The evolution of locomotion in archosaurs" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Palevol. 5 (3–4): 519–530. Bibcode:2006CRPal...5..519H. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.09.002.

- ^ Penn State (1 March 2005). "Global Warming Led To Atmospheric Hydrogen Sulfide And Permian Extinction". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05.

- ^ "The Day The Earth Nearly Died – programme summary". Science & Nature > TV & Radio Follow-up. BBC. Archived from the original on 2012-09-01.

- ^ Hayward, T. (1997). The First Dinosaurs. Dinosaur Cards. Orbis Publishing Ltd. D36040612.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C.; Catherine A. Forster; Raymond R. Rogers; Alfredo M. Monetta (January 1993). "Primitive dinosaur skeleton from Argentina and the early evolution of Dinosauria". Nature. 361 (6407): 64–66. Bibcode:1993Natur.361...64S. doi:10.1038/361064a0. S2CID 4270484.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (2006-01-26). "Dino-Era Fossil Reveals Two-Footed Croc Relative". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Burk, Angela; Michael Westerman; Mark Springer (September 1988). "The Phylogenetic Position of the Musky Rat-Kangaroo and the Evolution of Bipedal Hopping in Kangaroos (Macropodidae: Diprotodontia)". Systematic Biology. 47 (3): 457–474. doi:10.1080/106351598260824. PMID 12066687.

- ^ Prideaux, Gavin J.; Warburton, Natalie M. (2008). "A new Pleistocene tree-kangaroo (Diprotodontia: Macropodidae) from the Nullarbor Plain of south-central Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (2): 463–478. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[463:ANPTDM]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 84129882. Archived from the original on 2011-10-19. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ^ "Two-legged fox is nature conquering all, says wildlife expert". BBC News. 2023-01-05. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ Aerts, Peter; Evie E. Vereeckea; Kristiaan D'Aoûta (2006). "Locomotor versatility in the white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar): A spatiotemporal analysis of the bipedal, tripedal, and quadrupedal gaits". Journal of Human Evolution. 50 (5): 552–567. Bibcode:2006JHumE..50..552V. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.12.011. PMID 16516949.

- ^ Rose, M.D. (1976). "Bipedal behavior of olive baboons (Papio anubis) and its relevance to an understanding of the evolution of human bipedalism". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 44 (2): 247–261. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330440207. PMID 816205. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- ^ "Coquerel's Sifaka". Duke University Lemur Center. Archived from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ^ "Primate Factsheets: Gelada baboon (Theropithecus gelada) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology". Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ^ Kondō, Shirō (1985). Primate morphophysiology, locomotor analyses, and human bipedalism. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 978-4-13-066093-8.[page needed]

- ^ a b Daver G, Guy F, Mackaye HT, Likius A, Boisserie J, Moussa A, Pallas L, Vignaud P, Clarisse ND (2022-08-24). "Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad" (PDF). Nature. 609 (7925): 94–100. Bibcode:2022Natur.609...94D. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04901-z. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 36002567. S2CID 234630242. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-25.

- ^ "What Does It Mean To Be Human? – Walking Upright". Smithsonian Institution. August 14, 2016. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Videan, Elaine N.; McGrew, W.C. (2002-05-09). "Bipedality in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus): Testing hypotheses on the evolution of bipedalism". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 118 (2): 184–190. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10058. PMID 12012370. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Bauer, Harold (1976). "Chimpanzee bipedal locomotion in the Gombe National Park, East Africa". Primates. 18 (4): 913–921. doi:10.1007/BF02382940. S2CID 41892278.

- ^ Waldman, Dan (2004-07-21). "Monkey apes humans by walking on two legs". NBC News. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Crompton, R. H.; Thorpe, S. K. S. (2007-11-16). "Response to Comment on "Origin of Human Bipedalism As an Adaptation for Locomotion on Flexible Branches"". Science. 318 (5853): 1066. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1066C. doi:10.1126/science.1146580. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ "Walking tall after all". Research Intelligence. University of Liverpool. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Naish, Darren (April 28, 2008). "Bipedal orangs, gait of a dinosaur, and new-look Ichthyostega: exciting times in functional anatomy part I". Tetrapod Zoology. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012.

- ^ Sharma, Jayanth (2007-03-08). "The Story behind the Picture – Monitor Lizards Combat". Wildlife Times. Archived from the original (php) on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Alexander, R. McN. (2004-05-01). "Bipedal animals, and their differences from humans". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (5). Ingentaconnect.com: 321–330. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00289.x. PMC 1571302. PMID 15198697.

- ^ Huffard CL, Boneka F, Full RJ (2005). "Underwater bipedal locomotion by octopuses in disguise". Science. 307 (5717): 1927. doi:10.1126/science.1109616. PMID 15790846. S2CID 21030132.

- ^ Lovejoy, C.O. (1988). "Evolution of Human walking". Scientific American. 259 (5): 82–89. Bibcode:1988SciAm.259e.118L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1188-118. PMID 3212438.

- ^ McHenry, H. M. (2009). "Human Evolution". In Michael Ruse; Joseph Travis (eds.). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

- ^ Wayman, Erin (August 6, 2012). "Becoming Human: The Evolution of Walking Upright". Smithsonian.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014.

- ^ Steve Connor (13 December 2007). "A pregnant woman's spine is her flexible friend". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Quoting Whitcome KK, Shapiro LJ, Lieberman DE (December 2007). "Fetal load and the evolution of lumbar lordosis in bipedal hominins". Nature. 450 (7172): 1075–1078. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1075W. doi:10.1038/nature06342. PMID 18075592. S2CID 10158.

- ^ Amitabh Avasthi (December 12, 2007). "Why Pregnant Women Don't Tip Over". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 2008-09-11. This article has good pictures explaining the differences between bipedal and non-bipedal pregnancy loads.

- ^ Sylvester, Adam D. (2006). "Locomotor Coupling and the Origin of Hominin Bipedalism". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 242 (3): 581–590. Bibcode:2006JThBi.242..581S. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.04.016. PMID 16782133.

- ^ Kimura, Tasuku (2019). "How did humans acquire erect bipedal walking?". Anthropological Science. 127 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1537/ase.190219. S2CID 132162687.

- ^ Thorpe, S. K. S.; Holder, R. L.; Crompton, R. H. (2007). "Origin of Human Bipedalism as an Adaptation for Locomotion on Flexible Branches". Science. 316 (5829): 1328–1331. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1328T. doi:10.1126/science.1140799. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 20036393. PMID 17540902. S2CID 85992565.

- ^ Niemitz, Carsten (2010). "The evolution of the upright posture and gait—a review and a new synthesis". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (3): 241–263. Bibcode:2010NW.....97..241N. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0637-3. PMC 2819487. PMID 20127307.

- ^ Sigmon, Becky (1971). "Bipedal behavior and the emergence of erect posture in man". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 34 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330340105. PMID 4993117.

- ^ Ko, Kwang Hyun (2015). "Origins of Bipedalism". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 58 (6): 929–934. arXiv:1508.02739. Bibcode:2015arXiv150802739K. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132015060399. S2CID 761213.

- ^ Napier, JR (1964). The evolution of bipedal walking in the hominids. Archives de Biologie (Liege).

- ^ Sigmon, Becky (1971). "Bipedal behavior and the emergence of erect posture in man". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 58 (6): 929–934. arXiv:1508.02739. Bibcode:2015arXiv150802739K. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132015060399. PMID 4993117. S2CID 761213.

- ^ Day, MH (1986). Bipedalism: Pressures, origins and modes. Major topics in human evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Kwang Hyun, Ko (2015). "Origins of Bipedalism". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 58 (6): 929–934. arXiv:1508.02739. Bibcode:2015arXiv150802739K. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132015060399. S2CID 761213.

- ^ Richmond, B. G.; Strait, D. S. (2000). "Evidence that humans evolved from a knuckle-walking ancestor". Nature. 404 (6776): 382–385. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..382R. doi:10.1038/35006045. PMID 10746723. S2CID 4303978.

- ^ a b Dean, F. 2000. Primate diversity. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc: New York. Print.

- ^ Wheeler, P. E. (1984). "The Evolution of Bipedality and Loss of Functional Body Hair in Hominoids". Journal of Human Evolution. 13 (1): 91–98. Bibcode:1984JHumE..13...91W. doi:10.1016/s0047-2484(84)80079-2.

- ^ a b c Shreeve, James (July 1996). "Sunset on the savanna". Discover. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28.

- ^ Green, Alemseged, David, Zeresenay (2012). "Australopithecus afarensis Scapular Ontogeny, Function, and the Role of Climbing in Human Evolution". Science. 338 (6106): 514–517. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..514G. doi:10.1126/science.1227123. PMID 23112331. S2CID 206543814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thorpe, S. K.; Holder, R. L.; Crompton, R. H. (2007). "Origin of human bipedalism as an adaptation for locomotion on flexible branches". Science. 316 (5829): 1328–31. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1328T. doi:10.1126/science.1140799. PMID 17540902. S2CID 85992565.

- ^ Isbell LA, Young TP (1996). "The evolution of bipedalism in hominids and reduced group size in chimpanzees: alternative responses to decreasing resource availability". Journal of Human Evolution. 30 (5): 389–397. Bibcode:1996JHumE..30..389I. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0034.

- ^ Lewin, Roger; Swisher, Carl Celso; Curtis, Garniss H. (2000). Java man: how two geologists' dramatic discoveries changed our understanding of the evolutionary path to modern humans. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-80000-4.

- ^ Pontzer, H.; Raichlen, D. A.; Rodman, P. S. (2014). "Bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion in chimpanzees". Journal of Human Evolution. 66: 64–82. Bibcode:2014JHumE..66...64P. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.10.002. PMID 24315239.

- ^ a b Hunt, Kevin (February 1996). "The postural feeding hypothesis: an ecological model for the evolution of bipedalism". South African Journal of Science. 92: 77–90. Archived from the original on 2017-03-05.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (31 May 2007). "Walk Like an Orangutan: Ape's stroll through the trees may shed light on evolution of human bipedalism". Science Magazine.

- ^ Minkel, JR (31 May 2007). "Orangutans Show First Walking May Have Been on Trees". Scientific American.

- ^ Kaplan, Matt (31 May 2007). "Upright orangutans point way to walking". Nature Magazine.

- ^ Hooper, Rowan (31 May 2007). "Our upright walking started in the trees". New Scientist Magazine.

- ^ Thorpe, Susannah (2007). "Walking the walk: evolution of human bipedalism" (PDF). University of Birmingham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Stanford, Craig B. (February 2006). "Arboreal bipedalism in wild chimpanzees: Implications for the evolution of hominid posture and locomotion". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (2): 225–231. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20284. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 16288480.

- ^ T. Douglas Price; Gary M. Feinman (2003). Images of the Past, 5th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-340520-9.

- ^ Brunet M, Guy F, Pilbeam D, Mackaye HT, Likius A, et al. (11 July 2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969.

- ^ Suwa G, Kono RT, Simpson SW, Asfaw B, Lovejoy CO, White TD (2 October 2009). "Paleobiological implications of the Ardipithecus ramidus dentition" (PDF). Science. 326 (5949): 94–99. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...94S. doi:10.1126/science.1175824. PMID 19810195. S2CID 3744438. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ White TD, et al. (2009). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the paleobiology of early hominids". Science. 326 (5949): 75–86. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...75W. doi:10.1126/science.1175802. PMID 19810190. S2CID 20189444.

- ^ Reno PL, et al. (2010). "An enlarged postcranial sample confirms Australopithecus afarensis dimorphism was similar to modern humans". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 365 (1556): 3355–3363. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0086. PMC 2981962. PMID 20855309.

- ^ Harmon E (2009). "Size and shape variation in the proximal femur of Australopithecus africanus". J Hum Evol. 56 (6): 551–559. Bibcode:2009JHumE..56..551H. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.01.002. PMID 19446306.

- ^ Reno PL, Lovejoy CO (2015). "From Lucy to Kadanuumuu: Balanced analyses of Australopithecus afarensisassemblages confirm only moderate skeletal dimorphism". PeerJ. 3. e925. doi:10.7717/peerj.925. PMC 4419524. PMID 25945314.

- ^ a b Lovejoy CO (2009). "Reexamining human origins in light of Ardipithecus ramidus" (PDF). Science. 326 (5949): 74e1–8. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...74L. doi:10.1126/science.1175834. PMID 19810200. S2CID 42790876.

- ^ Lovejoy CO (1981). "The Origin of Man". Science. 211 (4480): 341–350. Bibcode:1981Sci...211..341L. doi:10.1126/science.211.4480.341. PMID 17748254.

- ^ Keith Oatley; Dacher Keltner; Jennifer M. Jenkins (2006). Understanding Emotion (2nd ed.). p. 235.

- ^ Prang, Thomas Cody (2019-04-30). "The African ape-like foot of Ardipithecus ramidus and its implications for the origin of bipedalism". eLife. 8 e44433. doi:10.7554/eLife.44433. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 6491036. PMID 31038121.

- ^ Kivell TL, Schmitt D (August 2009). "Independent evolution of knuckle-walking in African apes shows that humans did not evolve from a knuckle-walking ancestor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (34): 14241–6. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10614241K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901280106. PMC 2732797. PMID 19667206.

- ^ Joseph Jordania. Why do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution. Logos, 2011

- ^ Wheeler, P. E. (1984). "The evolution of bipedality and loss of functional body hair in hominids". J. Hum. Evol. 13 (1): 91–98. Bibcode:1984JHumE..13...91W. doi:10.1016/s0047-2484(84)80079-2.

- ^ Wheeler, P. E. (1990). "The influence of thermoregulatory selection pressures on hominid evolution". Behav. Brain Sci. 13 (2): 366. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00079218. S2CID 147314740.

- ^ Wheeler, P.E. (1991). "The influence of bipedalism on the energy and water budgets of early hominids". J. Hum. Evol. 21 (2): 117–136. Bibcode:1991JHumE..21..117W. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(91)90003-e.

- ^ David-Barrett, T.; Dunbar, R. (2016). "Bipedality and hair loss in human evolution revisited: The impact of altitude and activity scheduling". J. Hum. Evol. 94: 72–82. Bibcode:2016JHumE..94...72D. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.006. PMC 4874949. PMID 27178459.

- ^ Tanner, Nancy Makepeace (1981). On Becoming Human. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 2013-05-22.

- ^ Kuliukas, A. (2013). "Wading Hypotheses of the Origin of Human Bipedalism". Human Evolution. 28 (3–4): 213–236.

- ^ Hardy, Alister C. (1960). "Was man more aquatic in the past?" (PDF). New Scientist. 7 (174): 642–645. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- ^ Morgan, Elaine (1997). The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63518-0.

- ^ Meier, R. (2003). The complete idiot's guide to human prehistory. Alpha Books. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-02-864421-9.

- ^ Niemitz, Carsten (2004). Das Geheimnis des Aufrechten Gangs ~ Unsere Evolution Verlief Anders. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-51606-1.

- ^ Cunnane, Stephen C (2005). Survival of the fattest: the key to human brain evolution. World Scientific Publishing Company. pp. 259. ISBN 978-981-256-191-6.

- ^ Wrangham R, Cheney D, Seyfarth R, Sarmiento E (December 2009). "Shallow-water habitats as sources of fallback foods for hominins". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 140 (4): 630–42. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21122. PMID 19890871. S2CID 36325131.

- ^ Verhaegena M, Puechb PF, Munro S (2002). "Aquaboreal ancestors?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 17 (5): 212–217. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02490-4.

- ^ Roca, Albert (June 2024). The vocal origin of bipedalism: We walk because we talk (1st ed.). Falcons. ISBN 978-84-09-63260-2.

- ^ DeSilva, Jeremy (2021). First Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us Human. HarperCollins. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-06-293849-7.

- ^ Trevathan, Wenda R. (1996). "The Evolution of Bipedalism and Assisted Birth". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 10 (2): 287–290. doi:10.1525/maq.1996.10.2.02a00100. ISSN 0745-5194. JSTOR 649332. PMID 8744088.

- ^ Sylvester, Adam D. (2006). "Locomotor Coupling and the Origin of Hominin Bipedalism". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 242 (3): 581–590. Bibcode:2006JThBi.242..581S. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.04.016. PMID 16782133.

- ^ Lovejoy, C. Owen; McCollum, Melanie A. (2010). "Spinopelvic pathways to bipedality: why no hominids ever relied on a bent-hip-bent-knee gait". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 365 (1556): 3289–3299. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0112. ISSN 0962-8436. JSTOR 20778968. PMC 2981964. PMID 20855303.

- ^ a b c d e McMahon, Thomas A. (1984). Muscles, reflexes, and locomotion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02376-2.

- ^ a b Biewener, Andrew A.; Daniel, T. (2003). A moving topic: control and dynamics of animal locomotion. Vol. 6. pp. 387–8. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0294. ISBN 978-0-19-850022-3. PMC 2880073. PMID 20410030.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Pontzer, Herman (2012). "Ecological Energetics in Early Homo". Current Anthropology. 53 (S6): S346 – S358. doi:10.1086/667402. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 10.1086/667402. S2CID 31461168.

- ^ a b DeSilva, Jeremy (2021). First Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us Human. New York: Harper Collins.

- ^ Bramble, Dennis (1983). "Running and Breathing in Mammals". Science. 219 (4582): 251–256. Bibcode:1983Sci...219..251B. doi:10.1126/science.6849136. PMID 6849136. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Passive Dynamic Walking at Cornell". Ruina.tam.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

Further reading

[edit]- Darwin, C., "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex", Murray (London), (1871).

- Dart, R. A., "Australopithecus africanus: The Ape Man of South Africa" Nature, 145, 195–199, (1925).

- Dawkins, R., "The Ancestor's Tale", Weidenfeld and Nicolson (London), (2004).

- DeSilva, J., "First Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us Human" HarperCollins (New York), (2021)

- Hewes, G. W., "Food Transport and the Origin of Hominid Bipedalism" American Anthropologist, 63, 687–710, (1961).

- Hunt, K. D., "The Evolution of Human Bipedality" Journal of Human Evolution, 26, 183–202, (1994).

- Isaac, G. I., "The Archeological Evidence for the Activities of Early African Hominids" In:Early Hominids of Africa (Jolly, C.J. (Ed.)), Duckworth (London), 219–254, (1978).

- Jablonski, N.G.; Chaplin, G. (1993). "Origin of Habitual Terrestrial Bipedalism in the Ancestor of the Hominidae". Journal of Human Evolution. 24 (4): 259–280. Bibcode:1993JHumE..24..259J. doi:10.1006/jhev.1993.1021.

- Tanner, N. M., "On Becoming Human", Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), (1981)

- Wescott, R.W. (1967). "Hominid Uprightness and Primate Display". American Anthropologist. 69 (6): 738. doi:10.1525/aa.1967.69.6.02a00110.

- Wheeler, P. E. (1984) "The Evolution of Bipedality and Loss of Functional Body Hair in Hominoids." Journal of Human Evolution, 13, 91–98,

- Vrba, E. (1993). "The Pulse that Produced Us". Natural History. 102 (5): 47–51.

External links

[edit]Bipedalism

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Etymology

The term "bipedalism" derives from the Latin prefix bi- meaning "two" and pes, pedis meaning "foot," denoting locomotion using two feet.[9] The noun form "bipedalism," referring to the state or condition of having or using two feet for locomotion, first entered English in the late 19th century, around 1897, building on the earlier adjective "bipedal" attested from circa 1600.[10][11] An antecedent term, "bipedality," appeared as early as 1847 to describe the quality of being two-footed.[12] The concept gained traction in scientific discourse during the 1860s, amid debates on human origins spurred by Charles Darwin's evolutionary theories; in The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin emphasized bipedal posture as a distinguishing human trait enabling hand use for tools. Thomas Henry Huxley further advanced related terminology in his 1863 Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature, where he analyzed anatomical parallels in bipedal locomotion between humans and apes, influencing anthropological usage.[13] In biology and anthropology, "biped" denotes an organism with two feet (first used in 1646), "bipedal" describes the two-footed form or gait, and "bipedalism" specifies the locomotor behavior, with the terminology refining over time to differentiate obligate human upright walking from facultative two-footed movement in other species.[14]Facultative and Obligate Bipedalism

Facultative bipedalism refers to a form of locomotion in which an animal employs bipedal movement on an optional or temporary basis, often in response to specific environmental or behavioral contexts, while retaining the ability to use quadrupedal gaits for primary travel.[15] This mode allows flexibility, as seen in species like kangaroos that may hop bipedally when transporting loads or navigating certain terrains, but revert to quadrupedal support under normal conditions.[16] In contrast, obligate bipedalism constitutes the primary or exclusive mode of terrestrial locomotion, where the organism is anatomically and behaviorally committed to moving on two limbs and cannot sustain efficient quadrupedal progression.[2] Humans and birds exemplify this, having lost effective quadrupedal capabilities through evolutionary specialization.[17] Key distinctions between these forms lie in their energetic profiles and anatomical specializations. Facultative bipedalism typically incurs higher energy costs for sustained use compared to an animal's default quadrupedal mode, limiting it to short durations or specific tasks, whereas obligate bipedalism optimizes energy efficiency for prolonged distances in adapted species, such as through reduced metabolic expenditure during human walking relative to primate knuckle-walking.[18] Anatomically, obligate bipeds exhibit committed adaptations like a repositioned pelvis for weight transfer, an S-curved spine for balance, and enlarged gluteal muscles to stabilize upright posture, features absent or less pronounced in facultative forms that retain versatile skeletal designs for multiple gaits.[17] These differences underscore how facultative bipedalism maintains locomotor versatility without full skeletal reconfiguration, while obligate forms prioritize efficiency at the expense of multimodal flexibility.[19] From an evolutionary perspective, facultative bipedalism often represents a transitional stage in locomotor evolution, serving as an intermediate adaptation that allows experimentation with bipedal postures before the commitment to obligate forms in derived lineages.[20] This progression is evident in early hominins, where initial facultative behaviors facilitated environmental shifts, eventually yielding the specialized obligate bipedalism that defines modern humans amid open habitats.[21] Such transitions highlight bipedalism's role as a derived trait, evolving independently in lineages like archosaurs and primates through selective pressures favoring sustained upright movement.[22]Advantages and Costs

Evolutionary Advantages

Bipedalism confers significant energy efficiency advantages for long-distance travel, particularly in open habitats where sustained locomotion is essential. Studies comparing human bipedal walking to the quadrupedal locomotion of chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, demonstrate that human walking requires approximately 75% less energy than chimpanzee knuckle-walking at comparable speeds. This efficiency likely provided a selective advantage to early hominins by allowing greater foraging ranges with reduced caloric expenditure, facilitating survival in resource-scarce environments. An elevated eye level from bipedal posture enhances visibility and vigilance, enabling better detection of predators and prey across expansive terrains such as savannas. This adaptation improves situational awareness in open landscapes, where spotting distant threats or opportunities from a quadrupedal stance would be obstructed by tall grasses or uneven ground.[23] By freeing the forelimbs from locomotor duties, bipedalism allows for versatile use in carrying food, infants, or tools, which likely amplified foraging success and social behaviors in early hominins. This liberation of the upper limbs supported the development of manipulative skills, contributing to ecological and reproductive advantages without the constraints of quadrupedalism.[24] In equatorial open environments, bipedalism offers thermoregulatory benefits by reducing direct solar radiation on the body and increasing convective heat loss through exposure to higher winds and cooler air at elevated heights. Additionally, it facilitates greater evaporative cooling from exposed skin surfaces, aiding heat dissipation during prolonged activity in hot climates.[25] Across diverse taxa, bipedalism provides lineage-specific advantages; for instance, in theropod dinosaurs and their avian descendants, it supports efficient terrestrial locomotion while freeing forelimbs for functions like prey manipulation or eventual flight adaptations, enhancing overall locomotor versatility.[26]Physiological and Energetic Costs

Bipedal locomotion, modeled as an inverted pendulum where the body's center of mass vaults over the stance leg, inherently increases the risk of falls compared to quadrupedal gaits, as any perturbation can lead to instability and require rapid corrective actions.[27] This model contributes to higher injury rates, particularly in humans, where falls account for a significant portion of orthopedic trauma due to the elevated center of mass and reduced base of support.[28] The demands of maintaining balance in this posture also exacerbate joint stress, with the lumbar spine experiencing increased compressive and shear forces that predispose individuals to chronic issues.[27] The energetic costs of bipedalism include elevated metabolic demands for both static upright posture and dynamic movement, particularly in species not fully adapted to obligate bipedality. In humans, standing upright requires approximately 10-20% more energy than sitting, due to continuous muscle activation to counter gravity.[29] For locomotion, facultative bipeds like chimpanzees incur about 10% higher net metabolic costs during bipedal walking than quadrupedal knuckle-walking, reflecting inefficient gait mechanics such as bent-hip, bent-knee postures.[6] Even in humans, where bipedal walking is energetically efficient relative to body size, Obligate bipedalism imposes developmental vulnerabilities, particularly in infants, by delaying independent locomotion and extending periods of parental dependency. Human newborns, adapted to a narrow pelvis for bipedal efficiency, are born with immature motor control and reduced grasping ability in their feet, transformed from arboreal tools to weight-bearing structures, which hinders clinging to caregivers and prolongs helplessness.[30] This results in slower acquisition of locomotor skills, with infants requiring months of supported practice to achieve stable bipedal walking, contrasting with the more immediate quadrupedal proficiency in other primates.[31] The prolonged dependency fosters extended maternal investment, amplifying reproductive costs in obligate bipeds.[32] Pathological outcomes of bipedalism often stem from the circulatory and structural strains of upright posture, leading to orthopedic and vascular disorders. Lumbar lordosis, an adaptation to balance the torso over the pelvis, increases shear forces on intervertebral discs, contributing to chronic lower back pain in a substantial portion of the human population.[33] Vertical orientation also promotes venous pooling in the lower extremities, elevating the risk of varicose veins through sustained hydrostatic pressure that weakens vein walls and valves.[34] Similarly, the downward gravitational pull on abdominal contents in erect posture heightens susceptibility to inguinal hernias, where intra-abdominal pressure overcomes weakened inguinal canals evolved under quadrupedal constraints.[35] In facultative bipeds, such as Japanese macaques, the ability to revert to quadrupedalism mitigates these costs by allowing energy savings during prolonged travel, with bipedal walking consuming up to 140% more energy than quadrupedal modes due to suboptimal limb postures.[36] This flexibility reduces cumulative injury risk and metabolic burden compared to obligate bipeds, where exclusive reliance on two-legged support amplifies vulnerabilities without fallback options.[6]Mechanics of Bipedal Movement

Gait and Locomotion

Bipedal walking in humans is characterized by a cyclic gait consisting of stance and swing phases for each leg, with the stance phase comprising approximately 60% of the gait cycle. The stance phase begins with heel strike, where the heel contacts the ground ahead of the body, followed by foot flat as the entire sole makes contact, mid-stance when the body weight shifts fully onto the stance leg, heel-off as the heel rises, and toe-off when the toes leave the ground to initiate swing. This sequence allows for efficient forward progression while maintaining support. A key feature of human walking is the double support period, occurring twice per gait cycle—initially from heel strike of one foot to toe-off of the opposite foot, and terminally from heel-off to toe-off of the same foot—accounting for about 20% of the cycle and providing brief bilateral ground contact for stability during weight transfer.[37] In contrast, bipedal running introduces an aerial phase where both feet are off the ground, eliminating double support and relying on single-leg support during stance, which comprises roughly 40% of the cycle. The stance phase in running features initial contact (often midfoot), mid-stance with rapid force application, and toe-off with propulsion, while the flight phase follows, enabling higher speeds through elastic energy storage and release in tendons and muscles. Humans typically transition from walking to running at speeds around 2 m/s, where the energetic and mechanical demands shift to favor the ballistic dynamics of running over the vaulting mechanics of walking.[38] Kinematically, walking operates on an inverted pendular motion, where the body's center of mass vaults over the stiff stance leg like a pendulum, conserving energy through gravitational potential-to-kinetic exchange during leg swing and minimizing muscular work at preferred speeds. Running, however, employs ballistic motion, with the center of mass following a parabolic trajectory during the aerial phase, requiring active muscle input for propulsion and leg retraction to sustain momentum. This pendular efficiency in walking contributes to lower energy demands compared to running, particularly for endurance activities. The optimal human walking speed, around 1.4 m/s, minimizes the cost of transport—defined as energy expended per unit distance per body mass—which is notably lower in bipeds for sustained locomotion than in many quadrupeds, enhancing long-distance efficiency.[39][40] Variations in bipedal gait include arm swing, which counterbalances leg motion by swinging contralaterally to reduce rotational inertia and vertical ground reaction forces, thereby lowering metabolic cost by up to 12% when unrestricted. Ground reaction forces during walking exhibit an M-shaped vertical profile, peaking at heel strike (about 1.1 times body weight) and toe-off (about 1.2 times body weight), while the anterior-posterior forces show braking followed by propulsion phases; in running, these forces increase to 2-3 times body weight with a more pronounced vertical impulse during stance.[41][42]Balance and Stability