Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

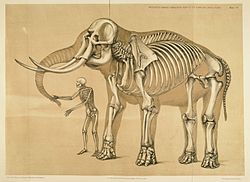

Comparative foot morphology

View on Wikipedia

Comparative foot morphology involves comparing the form of distal limb structures of a variety of terrestrial vertebrates. Understanding the role that the foot plays for each type of organism must take account of the differences in body type, foot shape, arrangement of structures, loading conditions and other variables. However, similarities also exist among the feet of many different terrestrial vertebrates. The paw of the dog, the hoof of the horse, the manus (forefoot) and pes (hindfoot) of the elephant, and the foot of the human all share some common features of structure, organization and function. Their foot structures function as the load-transmission platform which is essential to balance, standing and types of locomotion (such as walking, trotting, galloping and running).

The discipline of biomimetics applies the information gained by comparing the foot morphology of a variety of terrestrial vertebrates to human-engineering problems. For instance, it may provide insights that make it possible to alter the foot's load transmission in people who wear an external orthosis because of paralysis from spinal-cord injury, or who use a prosthesis following the diabetes-related amputation of a leg. Such knowledge can be incorporated in technology that improves a person's balance when standing; enables them to walk more efficiently, and to exercise; or otherwise enhances their quality of life by improving their mobility.

Structure

[edit]Limb and foot structure of representative terrestrial vertebrates:

Variability in scaling and limb coordination

[edit]

There is considerable variation in the scale and proportions of body and limb, as well as the nature of loading, during standing and locomotion both among and between quadrupeds and bipeds.[1] The anterior-posterior body mass distribution varies considerably among mammalian quadrupeds, which affects limb loading. When standing, many terrestrial quadrupeds support more of their weight on their forelimbs rather than their hind limbs;[2][3] however, the distribution of body mass and limb loading changes when they move.[4][5][6] Humans have a lower-limb mass that is greater than their upper-limb mass. The hind limbs of the dog and horse have a slightly greater mass than the forelimbs, whereas the elephant has proportionally longer limbs. The elephant's forelimbs are longer than its hind limbs.[7]

In the horse[8] and dog, the hind limbs play an important role in primary propulsion. The legged locomotion of humans generally distributes an equal loading on each lower limb.[9] The locomotion of the elephant (which is the largest terrestrial vertebrate) displays a similar loading distribution on its hind limbs and forelimbs.[10] The walking and running gaits of quadrupeds and bipeds show differences in the relative phase of the movements of their forelimbs and hind limbs, as well as of their right-side limbs versus their left-side limbs.[5][11] Many of the aforementioned variables are connected with differences in the scaling of body and limb dimension as well as in patterns of limb coordination and movement. However, little is understood concerning the functional contribution of the foot and its structures during the weight-bearing phase. The comparative morphology of the distal limb and foot structure of some representative terrestrial vertebrates reveals some interesting similarities.

Columnar organization of limb structures

[edit]

Even many terrestrial vertebrates exhibit differences in the scaling of limb dimension, limb coordination and magnitude of forelimb-hind limb loading, in the dog, horse and elephant the structure of the distal forelimb is similar to that of the distal hind limb.[7][8][12] In the human, the structures of the hand are generally similar in shape and arrangement to those of the foot. Terrestrial vertebrate quadrupeds and bipeds generally possess distal limb and foot endoskeleton structures that are aligned in series, stacked in a relatively vertical orientation and arranged in a quasi-columnar fashion in the extended limb.[1][13][14] In the dog and horse, the bones of the proximal limbs are oriented vertically, whereas the distal limb structures of the ankle and foot have an angulated orientation. In humans and elephants, a vertical-column orientation of the bones in the limbs and feet is also evident for associated skeletal muscle-tendon units.[6] The horse's foot contains an external nail (hoof) oriented about the perimeter in the shape of a semicircle. The underlying bones are arranged in a semi-vertical orientation.[15][16] The dog's paw similarly contains bones arranged in a semi-vertical orientation.

In the human and the elephant, the column orientation of the foot complex is replaced in humans by a plantigrade orientation, and in elephants by a semi-plantigrade alignment of the hind limb foot structure.[6] This difference in orientation in the foot bones and joints of humans and elephants helps them to adapt to variations in the terrain.[17]

Distal cushion

[edit]Many representative terrestrial vertebrates possess a distal cushion on the under-surface of the foot. The dog's paw contains a number of visco-elastic pads oriented along the middle and distal foot. The horse possesses a centralized digital pad known as the frog, which is located at the distal aspect of the foot and surrounded by the hoof.[12] Humans possess a tough fibro and elastic pad of fat that is anchored to the skin and bone of the rear portion of the foot.[18][19]

The foot of the elephant possesses what is perhaps one of the most unusual distal cushions found in vertebrates. The forefoot (manus) and hindfoot (pes) contain huge pads of fat that are scaled to cope with the massive loadings imposed by the largest terrestrial vertebrate. In addition, a cartilage-like projection (prepollex in the forelimb and prehallux in the hind limb) appears to anchor the distal cushion to the bones of the elephant's foot.[20]

The distal cushions of all these organisms (dog, horse, human and elephant) are dynamic structures during locomotion, alternating between phases of compression and expansion; it has been suggested that these structures thereby reduce the loads experienced by the skeletal system.[18][19][20][21]

Organization

[edit]Arrangement of foot structures:

Because of the wide variety in body types, scaling and morphology of the distal limbs of terrestrial vertebrates, there exists a degree of controversy concerning the nature and organization of foot structures. One organizational approach to understanding foot structures makes distinctions regarding their regional anatomy. The foot structures are divided into segments from proximal to distal and are grouped according to similarity in shape, dimension and function. In this approach, the foot may be described in three segments: as the hindfoot, midfoot and forefoot.

The hindfoot is the most proximal and posterior portion of the foot.[22] Functionally, the structures contained in this region are typically robust, possessing a larger size and girth than the other structures of the foot. The structures of the hindfoot are usually adapted for transmitting large loads between the proximal and distal aspects of the limb when the foot contacts the ground. This is apparent in the human and elephant foot, where the hindfoot undergoes greater loading during initial contact in many forms of locomotion.[23] The hindfoot structures of the dog and horse are located relatively proximally compared to the elephant and human foot.

The midfoot is the intermediate portion of the foot between the hindfoot and forefoot. The structures in this region are intermediate in size, and typically transmit loads from the hindfoot to the forefoot. The human transverse tarsal joint of the midfoot transmits forces from the subtalar joint in the hindfoot to the forefoot joints (metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal) and associated bones (metatarsals and phalanges).[24] The midfoot of the dog, horse and elephant contains similar intermediate structures having similar functions to those of the human midfoot.

The forefoot represents the most distal portion of the foot. In the human and elephant, the bone structures contained in this region are generally longer and narrower. The structures of the forefoot play a role in providing leverage for terminal stance propulsion and load transfer.[6][23]

Function

[edit]Load transmission of the foot in representative terrestrial vertebrates:

Dog paw

[edit]

The paw of the dog has a digitigrade orientation. The vertical columnar orientation of the proximal bones of the limbs, which articulate with distal foot structures that are arranged in quasi-vertical columnar orientation, is well-aligned to transmit loadings during weight-bearing contact of the skeleton with the ground. The angled orientation of the elongated metatarsal and the digits extends the area available for storing and releasing mechanical energy in the muscle tendon units originating proximally to the ankle joint and terminating at the distal aspect of the foot bones.[6] When muscle tendon units lengthen, the load strain facilitates mechanical activity. These muscle tendon unit structures appear well designed to aid in the ground-reaction transmission of forces that is essential for locomotion.[25] In addition, the pads of the distal paw appear to allow load attenuation, by enhancing shock absorption during the paw's contact with the ground.

Horse foot

[edit]

The horse's foot is in an unguligrade orientation. The columnar orientation of bones and connective tissue is similarly well-aligned to transmit loads during the weight-bearing phase of locomotion. The thick keratinized and semicircular hoof changes shape during loading and unloading. Similarly, the cushioned frog situated centrally at the rear ends of the hoof undergoes compression during loading, and expansion when unloaded. Together, the hoof and cushioned frog structures may work in concert with hoof capsule to provide shock absorption.[21] The horse hoof also acts dynamically during loading, which may cushion the endoskeleton from high loads that would otherwise produce critical deformation.

Elephant foot

[edit]

The hind limb and foot of the elephant are oriented semi-plantigrade, and closely resemble the structure and function of the human foot. The tarsals and metapodials are arranged so as to form an arch, similarly to the human foot. The six toes of each foot of the elephant are enclosed in a flexible sheath of skin.[20][26] Similar to the dog's paw, the elephant's phalanges are oriented in a downward direction. The distal phalanges of the elephant do not directly touch the ground, and are attached to the respective nail/hoof.[27] Distal cushions occupy the spaces between the muscle tendon units and ligaments within the hindfoot, midfoot and forefoot bones on the plantar surface.[28] The distal cushion is highly innervated by sensory structures (Meissner's and Pacinian corpuscles), making the distal foot one of the most sensitive structures of the elephant (more so than its trunk).[20] The cushions of the elephant's foot respond to the requirement to store and absorb mechanical loads when they are compressed, and to distribute locomotor loads over a large area in order to keep foot tissue stresses within acceptable levels.[20] In addition, the musculoskeletal foot arch and sole cushion of the elephant act in concert, similarly to the horse's cushioned frog and hoof[6] and the human foot.[29] In the elephant, the nearly half-cupula-shaped arrangement of the bony elements of the metatarsals and toes has interesting similarities to the structure of the arches of human feet.[29][30]

Recently, scientists at the Royal Veterinary College in the United Kingdom have discovered that the elephant possesses a sixth false toe, a sesamoid, located similarly to the giant panda's extra "thumb". They found that this sixth toe acts to support and distribute the weight of the elephant.[31]

Human foot

[edit]

The unique plantigrade alignment of the human foot results in a distal-limb structure that can adapt to a variety of conditions. The less mobile and more robust tarsal bones are shaped and aligned to accept and transmit large loads during the early phases of stance (initial contact and loading response phases of walking, and inadvertent heel strikes during running). The tarsals of the midfoot, which are smaller and shorter than the hindfoot tarsals, appear well oriented to transmit loads between the hindfoot and forefoot; this is necessary for load transfer and locking of the foot complex into a rigid lever for late stance phase. Conversely, the midfoot bones and joints also allow for the transmission of loads and inter-joint movement that unlocks the foot to create a loosely packed structure which renders the foot highly compliant over a variety of surfaces. In this configuration, the foot is able to absorb and damp the large loads encountered during heel strike and early weight acceptance.[17] The forefoot, with its long metatarsal and relatively long phalanges, transmits loads during the end-of-stance phase that facilitate the push-off and transfer of forward momentum. The forefoot also serves as a lever to allow balance during standing and jumping. In addition, the arches of the foot that span the hindfoot, midfoot and forefoot play a critical role in the nature of transformation of the foot from a rigid lever to a flexible weight-accepting structure.[23][24]

With a running gait, the foot-loading order is usually the reverse of walking. The foot strikes the ground with the ball of the foot, and then the heel drops.[32] The heel drop elastically extends the Achilles tendon; this extension is reversed during the push-off.[33]

Clinical implications

[edit]Veterinarian or human healthcare professionals often respond when the foot of a dog, horse, elephant or human develops an abnormality. They typically investigate to understand the nature of the pathology in order to generate and implement a clinical treatment plan. For instance, the paws of the dog and the hindfoot work together to absorb the shock of jumping and running, and to provide flexibility of movement. If the dog's skeletal structures in areas other than the foot are compromised, the foot may be burdened with compensatory loading. Structural faults such as straight or loose shoulders, straight stifles, loose hips, and lack of balance between the forefoot and hindfoot, can all cause gait abnormalities that in turn damage the hindfoot and paws by overloading their foot structures as they compensate for the structural faults.

In the horse, dryness of the hoof may cause stiffening of the external foot structure. The stiffer hoof reduces the foot's load attenuation capacity, rendering the horse unable to bear much weight on the distal limb. Similar characteristic features emerge in the human foot in the form of the pes cavus alignment deformity, which is produced by tight connective tissue structures and joint congruency that create a rigid foot complex. Individuals with pes cavus display characteristic reduced load-attenuation features, and other structures proximal to the foot may compensate with increased load transfer (i.e., excessive loading to the knees, hips, lumbo-pelvic joints or lumbar vertebrae).[24] Foot disorders are common in captive elephants. However, the cause is poorly understood.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lockley, M; Jackson, P (2008). "Morphodynamic perspectives on convergence between the feet and limbs of sauropods and humans: two cases of hypermorphosis". Ichnos. 15 (3–4): 140–157. Bibcode:2008Ichno..15..140L. doi:10.1080/10420940802467884. S2CID 86281623.

- ^ Lee, DV; Stakebake, EF; Walter, RM; Carrier, DR (2004). "Effects of mass distribution on the mechanics of level trotting in dogs". J Exp Biol. 207 (10): 1715–1728. doi:10.1242/jeb.00947. PMID 15073204.

- ^ Alexander, R McN; Maloiy, GMO; Hunter, B; Jayes, AS; j, Nturibi (1979). "Mechanical stresses in fast locomotion of buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and elephant (Loxodonta Africana)". J Zool. 189 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1979.tb03956.x.

- ^ DV, Lee; Sandord, GM (2005). "Directionally compliant legs influence the intrinsic pitch behavior of a trotting quadruped". Proc R Soc B (272): 567–572.

- ^ a b Griffin, TM; Main, RP; Farley, CT (2004). "Biomechanics of quadrupedal walking: how do four-legged animals achieve inverted pendulum-like movements?". J Exp Biol. 207 (20): 3545–3558. doi:10.1242/jeb.01177. PMID 15339951.

- ^ a b c d e f Weissengruber, GE; Forstenpointer, G (2004). "Shock absorbers and more: design principles of the lower hind limbs in African elephants (Loxodonta Africana)". J Morphol (260): 339.

- ^ a b Miller, CE; Basu, C; Fritsch, G; Hildebrandt, T; JR, Hutchinson (2008). "Ontogenetic scaling of foot musculoskeletal anatomy in elephants". J R Soc Interface. 5 (21): 465–475. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.1220. PMC 2607390. PMID 17974531.

- ^ a b Dutto, DJ; Hoyt, DF; Clayton, HM; Cogger, EA; SJ, Wickler (2006). "Joint Work and power for both the forelimb and hind limb during trotting in the horse". J Exp Biol. 209 (20): 3990–3999. doi:10.1242/jeb.02471. PMID 17023593.

- ^ Hessert, MJ; Vyas, M; Leach, J; Hu, K; LA Lipsitz; V Novak (2005). "Foot pressure distribution during walking in young and old adults". BMC Geriatrics. 5 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-5-8. PMC 1173105. PMID 15943881.

- ^ Hutchinson, FR; Famini, D; Lair, R; Kram, R (2003). "Are fast moving elephants really running?". Nature. 422 (6931): 493–494. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..493H. doi:10.1038/422493a. PMID 12673241. S2CID 4403723.

- ^ Beiwener, AA (2006). "Patterns of mechanical energy change in tetrapod gait: pendula, springs and work". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 305A (11): 899–911. Bibcode:2006JEZA..305..899B. doi:10.1002/jez.a.334. PMID 17029267.

- ^ a b McClure, RC (1999). "Functional Anatomy of the Horse Foot" (PDF). Agricultural MU Guide. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Howell, AB (1944). Speed in Animals: Their Specialization for Running and Leaping. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Gambaryan, PP (1974). How Mammals Run. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Douglas, JE; Mittal, C; Thomason, JJ; Jofriet, JC (1996). "The modulus of elasticity of equine hoof wall: implications for the mechanical function of the hoof". J Exp Biol. 199 (8): 1829–1836. doi:10.1242/jeb.199.8.1829. PMID 8708582.

- ^ Thompson, JJ; Biewener, AA; Bertram, JEA (1992). "Surface strain on the equine hoof wall in vivo: implications for the material design and functional morphology of the wall". J Exp Biol. 166 (166): 145–168. doi:10.1242/jeb.166.1.145.

- ^ a b Donatelli, R (1997). "The evolution and mechanics of the midfoot and hindfoot". Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 8 (1): 57–64. doi:10.3233/BMR-1997-8108. PMID 24572715.

- ^ a b Gefen, A; Ravid, MM; Itzchak, Y (2001). "In vivo biomechanical behavior of the human heel pad during the stance phase of gait". J Biomech. 34 (12): 1661–1665. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00143-9. PMID 11716870.

- ^ a b Miller-Young, JE; Duncan, NA; Baroud, G (2002). "Material properties of the human calcaneal fat pad in compression: experiment and theory". J Biomech. 35 (12): 1523–1531. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00090-8. PMID 12445605.

- ^ a b c d e Weissengruber, GE; Egger, GF; Hutchinson, JR; Groenewald, HB; L Elsasser; D Famini; G Forstenponter (2006). "The structure of the cushions in the feet of African elephants (Loxodonta Africana)". J Anat. 209 (6): 781–792. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00648.x. PMC 2048995. PMID 17118065.

- ^ a b König, HE; Macher, R; Polsterer-Heindl, E; Sora, CM; C Hinterhofer; M Helmreich; P Böck (2003). "Stroßbrechende Einrichtungen am Zehenendorgan des Pferdes". Wiener Tierarztliche Monatsschrift (90): 267–273.

- ^ McPoil TG, Brocato RS. The foot and ankle: biomechanical evaluation and treatment. In: Gould JA, Davies GJ, ed. Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1985.

- ^ a b c Perry, J (1992). Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Inc.

- ^ a b c Soderberg, GL (1997). Kinesiology Application to Pathological Motion (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ Fisher, MS; Witte, H (2007). "Legs evolved only at the end!". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 365 (1850): 185–198. Bibcode:2007RSPTA.365..185F. doi:10.1098/rsta.2006.1915. PMID 17148056. S2CID 20889363.

- ^ Weissengruber, GE; Forstenpointer, G (2004). "Musculature of the crus and pes of the African elephant (Loxodonta Africana): insight into semiplantigrade limb architecture". Anat Embryol. 208 (6): 451–461. doi:10.1007/s00429-004-0406-1. PMID 15340844. S2CID 2142971.

- ^ Smuts, MMS; Bezuidenhout, AJ (1994). "Osteology of the pelvic limb of the African elephant (Loxodonta Africana)". Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 61 (61): 51–66. PMID 7898898.

- ^ Benz, A (2005). "The elephant's hoof: macroscopic and microscopic morphology of defined locations under consideration of pathological changes". Inaugural Dissertation. Vetsuisse-Fakultät Universität Zürich.

- ^ a b Ker, RF; Bennett, MB; Bibby, SR; Kester, RC; Alexander, RMcN (1987). "The spring in the arch of the human foot". Nature. 325 (6100): 147–149. Bibcode:1987Natur.325..147K. doi:10.1038/325147a0. PMID 3808070. S2CID 4358258.

- ^ Tillmann, B. "Untere Extremität". In Leonhardt, H; Tillmann, B; Töndury, G; et al. (eds.). Anatomie des Menschen, Band I, Bewegungsapparat (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: Thieme. pp. 445–651.

- ^ "Elephants Have a Sixth 'Toe'". ScienceMag.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ Lieberman, Daniel E; Venkadesan, Madhusudhan; Daoud, Adam I; Werbel, William A (August 2010). "Biomechanics of Foot Strikes & Applications to Running Barefoot or in Minimal Footwear". Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ davejhavu (November 2007). "Favorite Runner 1". YouTube. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ Fowler, ME. "An overview of foot conditions in Asian and African elephants". In Csuti, B; Sargent, EL; Bechert, US (eds.). The elephant's foot. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. pp. 3–7.

External links

[edit]- Biomechatronics Group Web Site Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab

- Dynamic Structure of the Human Foot. Digital Resource Foundation for the Orthotics and Prosthetics Community. Virtual Project Library

- Center for Biologically Inspired Design at Georgia Tech

- Master of Science in Prosthetics and Orthotics Program at Georgia Tech

- Elephant Bibliographic Database

- John Hutchinson Web Site

- Research for this Wikipedia entry was conducted as a part of a Locomotion Neuromechanics course (APPH 6232) offered in the School of Applied Physiology at Georgia Tech