Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Timeline of human evolution

View on Wikipedia

The timeline of human evolution outlines the major events in the evolutionary lineage of the modern human species, Homo sapiens, throughout the history of life, beginning some 4 billion years ago down to recent evolution within H. sapiens during and since the Last Glacial Period.

It includes brief explanations of the various taxonomic ranks in the human lineage. The timeline reflects the mainstream views in modern taxonomy, based on the principle of phylogenetic nomenclature; in cases of open questions with no clear consensus, the main competing possibilities are briefly outlined.

Overview of taxonomic ranks

[edit]A tabular overview of the taxonomic ranking of Homo sapiens (with age estimates for each rank) is shown below.

| Rank | Name | Common name | Started (millions of years ago) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life | 4,200 | ||

| Archaea | 3,700 | ||

| Domain | Eukaryota | Eukaryotes | 2,100 |

| Opimoda | Excludes Plants and their relatives | 1,540 | |

| Amorphea | |||

| Obazoa | Excludes Amoebozoa (Amoebas) | ||

| Opisthokonta | Holozoa + Holomycota (Cristidicoidea and Fungi) | 1,300 | |

| Holozoa | Excludes Holomycota | 1,100 | |

| Filozoa | Choanozoa + Filasterea | ||

| Choanozoa | Choanoflagellates + Animals | 900 | |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animals | 610 |

| Subkingdom | Eumetazoa | Excludes Porifera (Sponges) | |

| Parahoxozoa | Excludes Ctenophora (Comb Jellies) | ||

| Bilateria | Triploblasts / Worms | 560 | |

| Nephrozoa | |||

| Deuterostomia | Division from Protostomes | ||

| Phylum | Chordata | Chordates (Vertebrates and closely related invertebrates) | 530 |

| Olfactores | Excludes cephalochordates (Lancelets) | ||

| Subphylum | Vertebrata | Fish / Vertebrates | 505 |

| Infraphylum | Gnathostomata | Jawed fish | 460 |

| Teleostomi | Bony fish | 420 | |

| Sarcopterygii | Lobe finned fish | ||

| Superclass | Tetrapoda | Tetrapods (animals with four limbs) | 395 |

| Amniota | Amniotes (fully terrestrial tetrapods whose eggs are "equipped with an amnion") | 340 | |

| Synapsida | Proto-Mammals | 308 | |

| Therapsida | Limbs beneath the body and other mammalian traits | 280 | |

| Class | Mammalia | Mammals | 220 |

| Subclass | Theria | Mammals that give birth to live young (i.e. non-egg-laying) | 160 |

| Infraclass | Eutheria | Placental mammals (i.e. non-marsupials) | 125 |

| Magnorder | Boreoeutheria | Supraprimates, (most) hoofed mammals, (most) carnivorous mammals, cetaceans, and bats | 124–101 |

| Superorder | Euarchontoglires | Supraprimates: primates, colugos, tree shrews, rodents, and rabbits | 100 |

| Grandorder | Euarchonta | Primates, colugos, and tree shrews | 99–80 |

| Mirorder | Primatomorpha | Primates and colugos | 79.6 |

| Order | Primates | Primates / Plesiadapiformes | 66 |

| Suborder | Haplorrhini | "Dry-nosed" (literally, "simple-nosed") primates: tarsiers and monkeys (incl. apes) | 63 |

| Infraorder | Simiiformes | monkeys (incl. apes) | 40 |

| Parvorder | Catarrhini | "Downward-nosed" primates: apes and old-world monkeys | 30 |

| Superfamily | Hominoidea | Apes: great apes and lesser apes (gibbons) | 22–20 |

| Family | Hominidae | Great apes: humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans—the hominids | 20–15 |

| Subfamily | Homininae | Humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas (the African apes)[1] | 14–12 |

| Tribe | Hominini | Includes both Homo and Pan (chimpanzees), but not Gorilla. | 10–8 |

| Subtribe | Hominina | Genus Homo and close human relatives and ancestors after splitting from Pan—the hominins | 8–4[2] |

| (Genus) | Ardipithecus s.l. | 6-4 | |

| (Genus) | Australopithecus | 3 | |

| Genus | Homo (H. habilis) | Humans | 2.5 |

| (Species) | H. erectus s.l. | ||

| (Species) | H. heidelbergensis s.l. | ||

| Species | Homo sapiens s.s. | Anatomically modern humans | 0.8–0.3[3] |

Timeline

[edit]−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unicellular life

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 4.3-4.1 Ga |

The earliest life appears, possibly as protocells. Their genetic material was probably composed of RNA, capable of both self replication and enzymatic activity; their membranes were composed of lipids. The genes were separate strands, translated into proteins and often exchanged between the protocells. |

| 4.0-3.8 Ga | Prokaryotic cells appear; their genetic materials are composed of the more stable DNA and they use proteins for various reasons, primarily for aiding DNA to replicate itself by proteinaceous enzymes (RNA now acts as an intermediary in this central dogma of genetic information flow of cellular life); genes are now linked in sequences so all information passes to offsprings. They had cell walls & outer membranes and were probably initially thermophiles. |

| 3.5 Ga | This marks the first appearance of cyanobacteria and their method of oxygenic photosynthesis and therefore the first occurrence of atmospheric oxygen on Earth.

For another billion years, prokaryotes would continue to diversify undisturbed. |

| 2.5-2.2 Ga | First organisms to use oxygen. By 2400 Ma, in what is referred to as the Great Oxidation Event, (GOE), most of the pre-oxygen anaerobic forms of life were wiped out by the oxygen producers. |

| 2.2-1.8 Ga | Origin of the eukaryotes: organisms with nuclei, endomembrane systems (including mitochondria) and complex cytoskeletons; they spliced mRNA between transcription and translation (splicing also occurs in prokaryotes, but it is only of non-coding RNAs). The evolution of eukaryotes, and possibly sex, is thought to be related to the GOE, as it probably pressured two or three lineages of prokaryotes (including an aerobe one, which later became mitochondria) to depend on each other, leading to endosymbiosis. Early eukaryotes lost their cell walls and outer membranes. |

| 1.2 Ga | Sexual reproduction evolves (mitosis and meiosis) by this time at least, leading to faster evolution[4] where genes are mixed in every generation enabling greater variation for subsequent selection. |

| 1.2-0.8 Ga |  The Holozoa lineage of eukaryotes evolves many features for making cell colonies, and finally leads to the ancestor of animals (metazoans) and choanoflagellates.[5][6] Proterospongia (members of the Choanoflagellata) are the best living examples of what the ancestor of all animals may have looked like. They live in colonies, and show a primitive level of cellular specialization for different tasks. |

Animalia

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 800–650 Ma |  Urmetazoan: The first fossils that might represent animals appear in the 665-million-year-old rocks of the Trezona Formation of South Australia. These fossils are interpreted as being early sponges.[7] Multicellular animals may have existed from 800 Ma. Separation from the Porifera (sponges) lineage. Eumetazoa/Diploblast: separation from the Ctenophora ("comb jellies") lineage. Planulozoa/ParaHoxozoa: separation from the Placozoa and Cnidaria lineages. All diploblasts possess epithelia, nerves, muscles and connective tissue and mouths, and except for placozoans, have some form of symmetry, with their ancestors probably having radial symmetry like that of cnidarians. Diploblasts separated their early embryonic cells into two germ layers (ecto- and endoderm). Photoreceptive eye-spots evolve. |

| 650-600 Ma |  Urbilaterian: the last common ancestor of xenacoelomorphs, protostomes (including the arthropod [insect, crustacean, spider], mollusc [squid, snail, clam] and annelid [earthworm] lineages) and the deuterostomes (including the vertebrate [human] lineage) (the last two are more related to each other and called Nephrozoa). Xenacoelomorphs all have a gonopore to expel gametes but nephrozoans merged it with their anus. Earliest development of bilateral symmetry, mesoderm, head (anterior cephalization) and various gut muscles (and thus peristalsis) and, in the Nephrozoa, nephridia (kidney precursors), coelom (or maybe pseudocoelom), distinct mouth and anus (evolution of through-gut), and possibly even nerve cords and blood vessels.[8] Reproductive tissue probably concentrates into a pair of gonads connecting just before the posterior orifice. "Cup-eyes" and balance organs evolve (the function of hearing added later as the more complex inner ear evolves in vertebrates). The nephrozoan through-gut had a wider portion in the front, called the pharynx. The integument or skin consists of an epithelial layer (epidermis) and a connective layer. |

| 600-540 Ma |  Most known animal phyla appeared in the fossil record as marine species during the Ediacaran-Cambrian explosion, probably caused by long scale oxygenation since around 585 Ma (sometimes called the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event or NOE) and also an influx of oceanic minerals. Deuterostomes, the last common ancestor of the Chordata [human] lineage, Hemichordata (acorn worms and graptolites) and Echinodermata (starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, etc.), probably had both ventral and dorsal nerve cords like modern acorn worms. An archaic survivor from this stage is the acorn worm, sporting an open circulatory system (with less branched blood vessels) with a heart that also functions as a kidney. Acorn worms have a plexus concentrated into both dorsal and ventral nerve cords. The dorsal cord reaches into the proboscis, and is partially separated from the epidermis in that region. This part of the dorsal nerve cord is often hollow, and may well be homologous with the brain of vertebrates.[9] Deuterostomes also evolved pharyngeal slits, which were probably used for filter feeding like in hemi- and proto-chordates. |

Chordata

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

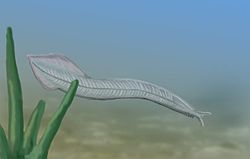

| 540-520 Ma |  The increased amount of oxygen causes many eukaryotes, including most animals, to become obligate aerobes. The Chordata ancestor gave rise to the lancelets (Amphioxii) and Olfactores. Ancestral chordates evolved a post-anal tail, notochord, and endostyle (precursor of thyroid). The pharyngeal slits (or gills) are now supported by connective tissue and used for filter feeding and possibly breathing. The first of these basal chordates to be discovered by science was Pikaia gracilens.[10] Other, earlier chordate predecessors include Myllokunmingia fengjiaoa,[11] Yunnanozoon lividum,[12] and Haikouichthys ercaicunensis.[13] They probably lost their ventral nerve cord and evolved a special region of the dorsal one, called the brain, with glia becoming permanently associated with neurons. They probably evolved the first blood cells (probably early leukocytes, indicating advanced innate immunity), which they made around the pharynx and gut.[14] All chordates except tunicates sport an intricate, closed circulatory system, with highly branched blood vessels. Olfactores, last common ancestor of tunicates and vertebrates in which olfaction (smell) evolved. Since lancelets lack a heart, it possibly emerged in this ancestor (previously the blood vessels themselves were contractile) though it could have been lost in lancelets after evolving in early deuterostomes (hemichordates and echinoderms have hearts). |

| 520-480 Ma |  The first vertebrates ("fish") appear: the Agnathans. They were jawless, had seven pairs of pharyngeal arches like their descendants today, and their endoskeletons were cartilaginous (then only consisting of the chondrocranium/braincase and vertebrae). The jawless Cyclostomata diverge at this stage. The connective tissue below the epidermis differentiates into the dermis and hypodermis.[15] They depended on gills for respiration and evolved the unique sense of taste (the remaining sense of the skin now called "touch"), endothelia, camera eyes and inner ears (capable of hearing and balancing; each consists of a lagena, an otolithic organ and two semicircular canals) as well as livers, thyroids, kidneys and two-chambered hearts (one atrium and one ventricle). They had a tail fin but lacked the paired (pectoral and pelvic) fins of more advanced fish. Brain divided into three parts (further division created distinct regions based on function). The pineal gland of the brain penetrates to the level of the skin on the head, making it seem like a third eye. They evolved the first erythrocytes and thrombocytes.[16] |

| 460-430 Ma |  The Placodermi were the first jawed fishes (Gnathostomata); their jaws evolved from the first gill/pharyngeal arch and they largely replaced their endoskeletal cartilage with bone and evolved pectoral and pelvic fins. Bones of the first gill arch became the upper and lower jaw, while those from the second arch became the hyomandibula, ceratohyal and basihyal; this closed two of the seven pairs of gills. The gap between the first and second arches just below the braincase (fused with upper jaw) created a pair of spiracles, which opened in the skin and led to the pharynx (water passed through them and left through gills). Placoderms had competition with the previous dominant animals, the cephalopods and sea scorpions, and rose to dominance themselves. A lineage of them probably evolved into the bony and cartilaginous fish, after evolving scales, teeth (which allowed the transition to full carnivory), stomachs, spleens, thymuses, myelin sheaths, hemoglobin and advanced, adaptive immunity (the latter two occurred independently in the lampreys and hagfish). Jawed fish also have a third, lateral semicircular canal and their otoliths are divided between a saccule and utricle. |

| 430-410 Ma |  |

Tetrapoda

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 390 Ma |  Some freshwater lobe-finned fish (sarcopterygii) develop limbs and give rise to the Tetrapodomorpha. These fish evolved in shallow and swampy freshwater habitats, where they evolved large eyes and spiracles. Primitive tetrapods ("fishapods") developed from tetrapodomorphs with a two-lobed brain in a flattened skull, a wide mouth and a medium snout, whose upward-facing eyes show that it was a bottom-dweller, and which had already developed adaptations of fins with fleshy bases and bones. (The "living fossil" coelacanth is a related lobe-finned fish without these shallow-water adaptations.) Tetrapod fishes used their fins as paddles in shallow-water habitats choked with plants and detritus. The universal tetrapod characteristics of front limbs that bend backward at the elbow and hind limbs that bend forward at the knee can plausibly be traced to early tetrapods living in shallow water.[18] Panderichthys is a 90–130 cm (35–50 in) long fish from the Late Devonian period (380 Mya). It has a large tetrapod-like head. Panderichthys exhibits features transitional between lobe-finned fishes and early tetrapods. Trackway impressions made by something that resembles Ichthyostega's limbs were formed 390 Ma in Polish marine tidal sediments. This suggests tetrapod evolution is older than the dated fossils of Panderichthys through to Ichthyostega. |

| 375-350 Ma |  Tiktaalik is a genus of sarcopterygian (lobe-finned) fishes from the late Devonian with many tetrapod-like features. It shows a clear link between Panderichthys and Acanthostega.   Acanthostega is an extinct tetrapod, among the first animals to have recognizable limbs. It is a candidate for being one of the first vertebrates to be capable of coming onto land. It lacked wrists, and was generally poorly adapted for life on land. The limbs could not support the animal's weight. Acanthostega had both lungs and gills, also indicating it was a link between lobe-finned fish and terrestrial vertebrates. The dorsal pair of ribs form a rib cage to support the lungs, while the ventral pair disappears. Ichthyostega is another extinct tetrapod. Being one of the first animals with only two pairs of limbs (also unique since they end in digits and have bones), Ichthyostega is seen as an intermediate between a fish and an amphibian. Ichthyostega had limbs but these probably were not used for walking. They may have spent very brief periods out of water and would have used their limbs to paw their way through the mud.[19] They both had more than five digits (eight or seven) at the end of each of their limbs, and their bodies were scaleless (except their bellies, where they remained as gastralia). Many evolutionary changes occurred at this stage: eyelids and tear glands evolved to keep the eyes wet out of water and the eyes became connected to the pharynx for draining the liquid; the hyomandibula (now called columella) shrank into the spiracle, which now also connected to the inner ear at one side and the pharynx at another, becoming the Eustachian tube (columella assisted in hearing); an early eardrum (a patch of connective tissue) evolved on the end of each tube (called the otic notch); and the ceratohyal and basihyal merged into the hyoid. These "fishapods" had more ossified and stronger bones to support themselves on land (especially skull and limb bones). Jaw bones fuse together while gill and opercular bones disappear. |

| 350-330 Ma |  Pederpes from around 350 Ma indicates that the standard number of 5 digits evolved at the Early Carboniferous, when modern tetrapods (or "amphibians") split in two directions (one leading to the extant amphibians and the other to amniotes). At this stage, our ancestors evolved vomeronasal organs, salivary glands, tongues, parathyroid glands, three-chambered hearts (with two atria and one ventricle) and bladders, and completely removed their gills by adulthood. The glottis evolves to prevent food going into the respiratory tract. Lungs and thin, moist skin allowed them to breathe; water was also needed to give birth to shell-less eggs and for early development. Dorsal, anal and tail fins all disappeared. Lissamphibia (extant amphibians) retain many features of early amphibians but they have only four digits (caecilians have none). |

| 330-300 Ma |  From amphibians came the first amniotes: Hylonomus, a primitive reptile, is the earliest amniote known. It was 20 cm (8 in) long (including the tail) and probably would have looked rather similar to modern lizards. It had small sharp teeth and probably ate small millipedes and insects. It is a precursor of later amniotes (including both the reptiles and the ancestors of mammals). Alpha keratin first evolves here; it is used in the claws of modern amniotes, and hair in mammals, indicating claws and a different type of scales evolved in amniotes (complete loss of gills as well).[20] Evolution of the amniotic egg allows the amniotes to reproduce on land and lay shelled eggs on dry land. They did not need to return to water for reproduction nor breathing. This adaptation and the desiccation-resistant scales gave them the capability to inhabit the uplands for the first time, albeit making them drink water through their mouths. At this stage, adrenal tissue may have concentrated into discrete glands. Amniotes have advanced nervous systems, with twelve pairs of cranial nerves, unlike lower vertebrates. They also evolved true sternums but lost their eardrums and otic notches (hearing only by columella bone conduction). |

Mammalia

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 300-260 Ma | Shortly after the appearance of the first amniotes, two branches split off. One branch is the Sauropsida, from which come the reptiles, including birds. The other branch is Synapsida, from which come modern mammals. Both had temporal fenestrae, a pair of holes in their skulls behind the eyes, which were used to increase the space for jaw muscles. Synapsids had one opening on each side, while diapsids (a branch of Sauropsida) had two. An early, inefficient version of diaphragm may have evolved in synapsids.

The earliest synapsids, or "proto-mammals," are the pelycosaurs. The pelycosaurs were the first animals to have temporal fenestrae. Pelycosaurs were not therapsids but their ancestors. The therapsids were, in turn, the ancestors of mammals. The therapsids had temporal fenestrae larger and more mammal-like than pelycosaurs, their teeth showed more serial differentiation, their gait was semi-erect and later forms had evolved a secondary palate. A secondary palate enables the animal to eat and breathe at the same time and is a sign of a more active, perhaps warm-blooded, way of life.[21] They had lost gastralia and, possibly, scales. |

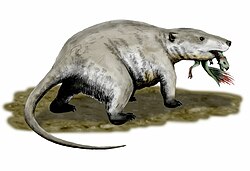

| 260-230 Ma |  One subgroup of therapsids, the cynodonts, lose pineal eye and lumbar ribs and very likely became warm-blooded. The lower respiratory tract forms intricate branches in the lung parenchyma, ending in highly vascularized alveoli. Erythrocytes and thrombocytes lose their nuclei while lymphatic systems and advanced immunity emerge. They may have also had thicker dermis like mammals today. The jaws of cynodonts resembled modern mammal jaws; the anterior portion, the dentary, held differentiated teeth. This group of animals likely contains a species which is the ancestor of all modern mammals. Their temporal fenestrae merged with their orbits. Their hindlimbs became erect and their posterior bones of the jaw progressively shrunk to the region of the columella.[22] |

| 230-170 Ma |  From Eucynodontia came the first mammals. Most early mammals were small shrew-like animals that fed on insects and had transitioned to nocturnality to avoid competition with the dominant archosaurs — this led to the loss of the vision of red and ultraviolet light (ancestral tetrachromacy of vertebrates reduced to dichromacy). Although there is no evidence in the fossil record, it is likely that these animals had a constant body temperature, hair and milk glands for their young (the glands stemmed from the milk line). The neocortex (part of the cerebrum) region of the brain evolves in Mammalia, at the reduction of the tectum (non-smell senses which were processed here became integrated into neocortex but smell became primary sense). Origin of the prostate gland and a pair of holes opening to the columella and nearby shrinking jaw bones; new eardrums stand in front of the columella and Eustachian tube. The skin becomes hairy, glandular (glands secreting sebum and sweat) and thermoregulatory. Teeth fully differentiate into incisors, canines, premolars and molars; mammals become diphyodont and possess developed diaphragms and males have internal penises. All mammals have four chambered hearts (with two atria and two ventricles) and lack cervical ribs (now mammals only have thoracic ribs). Monotremes are an egg-laying group of mammals represented today by the platypus and echidna. Recent genome sequencing of the platypus indicates that its sex genes are closer to those of birds than to those of the therian (live birthing) mammals. Comparing this to other mammals, it can be inferred that the first mammals to gain sexual differentiation through the existence or lack of SRY gene (found in the y-Chromosome) evolved only in the therians. Early mammals and possibly their eucynodontian ancestors had epipubic bones, which serve to hold the pouch in modern marsupials (in both sexes). |

| 170-120 Ma |  Evolution of live birth (viviparity), with early therians probably having pouches for keeping their undeveloped young like in modern marsupials. Nipples stemmed out of the therian milk lines. The posterior orifice separates into anal and urogenital openings; males possess an external penis. Monotremes and therians independently detach the malleus and incus from the dentary (lower jaw) and combine them to the shrunken columella (now called stapes) in the tympanic cavity behind the eardrum (which is connected to the malleus and held by another bone detached from the dentary, the tympanic plus ectotympanic), and coil their lagena (cochlea) to advance their hearing, with therians further evolving an external pinna and erect forelimbs. Female placentalian mammals do not have pouches and epipubic bones but instead have a developed placenta which penetrates the uterus walls (unlike marsupials), allowing a longer gestation; they also have separated urinary and genital openings.[23] |

| 100-90 Ma | Last common ancestor of rodents, rabbits, ungulates, carnivorans, bats, shrews and humans (base of the clade Boreoeutheria; males now have external testicles). |

Primates

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 90–66 Ma |   A group of small, nocturnal, arboreal, insect-eating mammals called Euarchonta begins a speciation that will lead to the orders of primates, treeshrews and flying lemurs. They reduced the number of mammaries to only two pairs (on the chest). Primatomorpha is a subdivision of Euarchonta including primates and their ancestral stem-primates Plesiadapiformes. An early stem-primate, Plesiadapis, still had claws and eyes on the side of the head, making it faster on the ground than in the trees, but it began to spend long times on lower branches, feeding on fruits and leaves. The Plesiadapiformes very likely contain the ancestor species of all primates.[24] They first appeared in the fossil record around 66 million years ago, soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that eliminated about three-quarters of plant and animal species on Earth, including most dinosaurs.[25][26] One of the last Plesiadapiformes is Carpolestes simpsoni, having grasping digits but not forward-facing eyes. |

| 66-56 Ma | Primates diverge into suborders Strepsirrhini (wet-nosed primates) and Haplorrhini (dry-nosed primates). Brain expands and cerebrum divides into 4 pairs of lobes. The postorbital bar evolves to separate the orbit from the temporal fossae as sight regains its position as the primary sense; eyes became forward-facing. Strepsirrhini contain most prosimians; modern examples include lemurs and lorises. The haplorrhines include the two living groups: prosimian tarsiers, and simian monkeys, including apes. The Haplorrhini metabolism lost the ability to produce vitamin C, forcing all descendants to include vitamin C-containing fruit in their diet. Early primates only had claws in their second digits; the rest were turned into nails. |

| 50-35 Ma |  Simians split into infraorders Platyrrhini and Catarrhini. They fully transitioned to diurnality and lacked any claw and tapetum lucidum (which evolved many times in various vertebrates). They possibly evolved at least some of the paranasal sinuses, and transitioned from estrous cycle to menstrual cycle. The number of mammaries is now reduced to only one thoracic pair. Platyrrhines, New World monkeys, have prehensile tails and males are color blind. The individuals whose descendants would become Platyrrhini are conjectured to have migrated to South America either on a raft of vegetation or via a land bridge (the hypothesis now favored[27]). Catarrhines mostly stayed in Africa as the two continents drifted apart. Possible early ancestors of catarrhines include Aegyptopithecus and Saadanius. |

| 35-20 Ma |  Catarrhini splits into 2 superfamilies, Old World monkeys (Cercopithecoidea) and apes (Hominoidea). Human trichromatic color vision had its genetic origins in this period. Catarrhines lost the vomeronasal organ (or possibly reduced it to vestigial status). Proconsul was an early genus of catarrhine primates. They had a mixture of Old World monkey and ape characteristics. Proconsul's monkey-like features include thin tooth enamel, a light build with a narrow chest and short forelimbs, and an arboreal quadrupedal lifestyle. Its ape-like features are its lack of a tail, ape-like elbows, and a slightly larger brain relative to body size. Proconsul africanus is a possible ancestor of both great and lesser apes, including humans. |

Hominidae

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 20-15 Ma | Hominidae (great ape ancestors) speciate from the ancestors of the gibbon (lesser apes) between c. 20 to 16 Ma. They largely reduced their ancestral snout and lost the uricase enzyme (present in most organisms).[28] |

| 16-12 Ma | Homininae ancestors speciate from the ancestors of the orangutan between c. 18 to 14 Ma.[29]

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus is thought to be a common ancestor of humans and the other great apes, or at least a species that brings us closer to a common ancestor than any previous fossil discovery. It had the special adaptations for tree climbing as do present-day humans and other great apes: a wide, flat rib cage, a stiff lower spine, flexible wrists, and shoulder blades that lie along its back. |

| 12 Ma | Danuvius guggenmosi is the first-discovered Late Miocene great ape with preserved long bones, and greatly elucidates the anatomical structure and locomotion of contemporary apes.[30] It had adaptations for both hanging in trees (suspensory behavior) and walking on two legs (bipedalism)—whereas, among present-day hominids, humans are better adapted for the latter and the others for the former. Danuvius thus had a method of locomotion unlike any previously known ape called "extended limb clambering", walking directly along tree branches as well as using arms for suspending itself. The last common ancestor between humans and other apes possibly had a similar method of locomotion. |

| 12-8 Ma | The clade currently represented by humans and the genus Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos) splits from the ancestors of the gorillas between c. 12 to 8 Ma.[31] |

| 8-6 Ma |  Hominini: The latest common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is estimated to have lived between roughly 10 to 5 million years ago. Both chimpanzees and humans have a larynx that repositions during the first two years of life to a spot between the pharynx and the lungs, indicating that the common ancestors have this feature, a precondition for vocalized speech in humans. Speciation may have begun shortly after 10 Ma, but late admixture between the lineages may have taken place until after 5 Ma. Candidates of Hominina or Homininae species which lived in this time period include Graecopithecus (c. 7 Ma), Sahelanthropus tchadensis (c. 7 Ma), Orrorin tugenensis (c. 6 Ma).  Ardipithecus was arboreal, meaning it lived largely in the forest where it competed with other forest animals for food, no doubt including the contemporary ancestor of the chimpanzees. Ardipithecus was probably bipedal as evidenced by its bowl shaped pelvis, the angle of its foramen magnum and its thinner wrist bones, though its feet were still adapted for grasping rather than walking for long distances. |

| 4-3.5 Ma |  A member of the Australopithecus afarensis left human-like footprints on volcanic ash in Laetoli, northern Tanzania, providing strong evidence of full-time bipedalism. Australopithecus afarensis lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago, and is considered one of the earliest hominins—those species that developed and comprised the lineage of Homo and Homo's closest relatives after the split from the line of the chimpanzees. It is thought that A. afarensis was ancestral to both the genus Australopithecus and the genus Homo. Compared to the modern and extinct great apes, A. afarensis had reduced canines and molars, although they were still relatively larger than in modern humans. A. afarensis also has a relatively small brain size (380–430 cm3) and a prognathic (anterior-projecting) face. Australopithecines have been found in savannah environments; they probably developed their diet to include scavenged meat. Analyses of Australopithecus africanus lower vertebrae suggests that these bones changed in females to support bipedalism even during pregnancy. |

| 3.5–3.0 Ma | Kenyanthropus platyops, a possible ancestor of Homo, emerges from the Australopithecus. Stone tools are deliberately constructed, possibly by Kenyanthropus platyops or Australopithecus afarensis.[34] |

| 3 Ma | The bipedal australopithecines (a genus of the subtribe Hominina) evolve in the savannas of Africa being hunted by Megantereon. Loss of body hair occurs from 3 to 2 Ma, in parallel with the development of full bipedalism and slight enlargement of the brain.[35] |

Homo

[edit]−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 2.8–2.0 Ma |

Early Homo appears in East Africa, speciating from australopithecine ancestors. The Lower Paleolithic is defined by the beginning of use of stone tools. Australopithecus garhi was using stone tools at about 2.5 Ma. Homo habilis is the oldest species given the designation Homo, by Leakey et al. in 1964. H. habilis is intermediate between Australopithecus afarensis and H. erectus, and there have been suggestions to re-classify it within genus Australopithecus, as Australopithecus habilis. LD 350-1 is now considered the earliest known specimen of the genus Homo, dating to 2.75–2.8 Ma, found in the Ledi-Geraru site in the Afar Region of Ethiopia. It is currently unassigned to a species, and it is unclear if it represents the ancestor to H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, which are estimated to have evolved around 2.4 Ma.[36] Stone tools found at the Shangchen site in China and dated to 2.12 million years ago are considered the earliest known evidence of hominins outside Africa, surpassing Dmanisi hominins found in Georgia by 300,000 years, although whether these hominins were an early species in the genus Homo or another hominin species is unknown.[37] |

| 1.9–0.8 Ma |  Homo erectus derives from early Homo or late Australopithecus. Homo habilis, although significantly different of anatomy and physiology, is thought to be the ancestor of Homo ergaster, or African Homo erectus; but it is also known to have coexisted with H. erectus for almost half a million years (until about 1.5 Ma). From its earliest appearance at about 1.9 Ma, H. erectus is distributed in East Africa and Southwest Asia (Homo georgicus). H. erectus is the first known species to develop control of fire, by about 1.5 Ma. H. erectus later migrates throughout Eurasia, reaching Southeast Asia by 0.7 Ma. It is described in a number of subspecies.[38] Early humans were social and initially scavenged, before becoming active hunters. The need to communicate and hunt prey efficiently in a new, fluctuating environment (where the locations of resources need to be memorized and told) may have driven the expansion of the brain from 2 to 0.8 Ma. Evolution of dark skin at about 1.2 Ma.[39] Homo antecessor may be a common ancestor of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.[40][41] At present estimate, humans have approximately 20,000–25,000 genes and share 99% of their DNA with the now extinct Neanderthal[42] and 95–99% of their DNA with their closest living evolutionary relative, the chimpanzees.[43][44] The human variant of the FOXP2 gene (linked to the control of speech) has been found to be identical in Neanderthals.[45] |

| 0.8–0.3 Ma |  Divergence of Neanderthal and Denisovan lineages from a common ancestor.[46] Homo heidelbergensis (in Africa also known as Homo rhodesiensis) had long been thought to be a likely candidate for the last common ancestor of the Neanderthal and modern human lineages. However, genetic evidence from the Sima de los Huesos fossils published in 2016 seems to suggest that H. heidelbergensis in its entirety should be included in the Neanderthal lineage, as "pre-Neanderthal" or "early Neanderthal", while the divergence time between the Neanderthal and modern lineages has been pushed back to before the emergence of H. heidelbergensis, to about 600,000 to 800,000 years ago, the approximate age of Homo antecessor.[47][48] Brain expansion (enlargement) between 0.8 and 0.2 Ma may have occurred due to the extinction of most African megafauna (which made humans feed from smaller prey and plants, which required greater intelligence due to greater speed of the former and uncertainty about whether the latter were poisonous or not), extreme climate variability after Mid-Pleistocene Transition (which intensified the situation, and resulted in frequent migrations), and in general selection for more social life (and intelligence) for greater chance of survival, reproductivity, and care for mothers. Solidified footprints dated to about 350 ka and associated with H. heidelbergensis were found in southern Italy in 2003.[49] H. sapiens lost the brow ridges from their hominid ancestors as well as the snout completely, though their noses evolve to be protruding (possibly from the time of H. erectus). By 200 ka, humans had stopped their brain expansion. |

Homo sapiens

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 300–130 ka |  Neanderthals and Denisovans emerge from the northern Homo heidelbergensis lineage around 500-450 ka while sapients emerge from the southern lineage around 350-300 ka.[50] Fossils attributed to H. sapiens, along with stone tools, dated to approximately 300,000 years ago, found at Jebel Irhoud, Morocco[51] yield the earliest fossil evidence for anatomically modern Homo sapiens. Modern human presence in East Africa (Gademotta), at 276 kya.[52] In July 2019, anthropologists reported the discovery of 210,000 year old remains of what may possibly have been a H. sapiens in Apidima Cave, Peloponnese, Greece.[53][54][55] Patrilineal and matrilineal most recent common ancestors (MRCAs) of living humans roughly between 200 and 100 kya[56][57] with some estimates on the patrilineal MRCA somewhat higher, ranging up to 250 to 500 kya.[58] 160,000 years ago, Homo sapiens idaltu in the Awash River Valley (near present-day Herto village, Ethiopia) practiced excarnation.[59] |

| 130–80 ka | Marine Isotope Stage 5 (Eemian).

Modern human presence in Southern Africa and West Africa.[60] Appearance of mitochondrial haplogroup (mt-haplogroup) L2. |

| 80–50 ka | MIS 4, beginning of the Upper Paleolithic.

Early evidence for behavioral modernity.[61] Appearance of mt-haplogroups M and N. Southern Dispersal migration out of Africa, Proto-Australoid peopling of Oceania.[62] Archaic admixture from Neanderthals in Eurasia,[63][64] from Denisovans in Oceania with trace amounts in Eastern Eurasia,[65] and from an unspecified African lineage of archaic humans in Sub-Saharan Africa as well as an interbred species of Neanderthals and Denisovans in Asia and Oceania.[66][67][68][69] |

| 50–25 ka |

Behavioral modernity develops by this time or earlier, according to the "great leap forward" theory.[70] Extinction of Homo floresiensis.[71] M168 mutation (carried by all non-African males). Appearance of mt-haplogroups U and K. Peopling of Europe, peopling of the North Asian Mammoth steppe. Paleolithic art. Extinction of Neanderthals and other archaic human variants (with possible survival of hybrid populations in Asia and Africa). Appearance of Y-Haplogroup R2; mt-haplogroups J and X. |

| after 25 ka |  Last Glacial Maximum; Epipaleolithic / Mesolithic / Holocene. Peopling of the Americas. Appearance of: Y-Haplogroup R1a; mt-haplogroups V and T. Various recent divergence associated with environmental pressures, e.g. light skin in Europeans and East Asians (KITLG, ASIP), after 30 ka;[72] Inuit adaptation to high-fat diet and cold climate, 20 ka.[73] Extinction of late surviving archaic humans at the beginning of the Holocene (12 ka). Accelerated divergence due to selection pressures in populations participating in the Neolithic Revolution after 12 ka, e.g. East Asian types of ADH1B associated with rice domestication,[74] or lactase persistence.[75][76] The past 100,000 years have seen selective reductions in brain size for some human lineages during warmer interglacial periods.[77] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Finarelli, John A.; Clyde, William C. (2004). "Reassessing hominoid phylogeny: Evaluating congruence in the morphological and temporal data". Paleobiology. 30 (4): 614. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0614:RHPECI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D (2006). "Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 441 (7097): 1103–08. Bibcode:2006Natur.441.1103P. doi:10.1038/nature04789. PMID 16710306. S2CID 2325560.

- ^ Depending on the classification of the Homo heidelbergensis lineage; 0.8 if Neanderthals are classed as H. sapiens neanderthalensis, or if H. sapiens is defined cladistically from the divergence from H. neanderthalensis, 0.3 based on the available fossil evidence.

- ^ "'Experiments with sex have been very hard to conduct,' Goddard said. 'In an experiment, one needs to hold all else constant, apart from the aspect of interest. This means that no higher organisms can be used, since they have to have sex to reproduce and therefore provide no asexual control.'

Goddard and colleagues instead turned to a single-celled organism, yeast, to test the idea that sex allows populations to adapt to new conditions more rapidly than asexual populations." Sex Speeds Up Evolution, Study Finds (URL accessed on January 9, 2005) - ^ Dawkins, R. (2005), The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0

- ^ "Proterospongia is a rare freshwater protist, a colonial member of the Choanoflagellata." "Proterospongia itself is not the ancestor of sponges. However, it serves as a useful model for what the ancestor of sponges and other metazoans may have been like." http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/protista/proterospongia.html Berkeley University

- ^ Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. (17 August 2010). "Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia". Nature Geoscience. 3 (9): 653–59. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934. S2CID 13171894.

- ^ Monahan-Earley, R.; Dvorak, A. M.; Aird, W. C. (2013). "Evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and endothelium". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 11 (Suppl 1): 46–66. doi:10.1111/jth.12253. PMC 5378490. PMID 23809110.

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 1018–26. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ "Obviously vertebrates must have had ancestors living in the Cambrian, but they were assumed to be invertebrate forerunners of the true vertebrates — proto-chordates. Pikaia has been heavily promoted as the oldest fossil protochordate." Richard Dawkins 2004 The Ancestor's Tale p. 289, ISBN 0-618-00583-8

- ^ Shu, D.G.; Luo, H.L.; Conway Morris, S.; Zhang, X. L.; Hu, S.X.; Chen, L.; Han, J.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.Z. (1999). "Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China". Nature. 402 (6757): 42–46. Bibcode:1999Natur.402...42S. doi:10.1038/46965. S2CID 4402854.

- ^ Chen, J.Y.; Huang, D.Y.; Li, C.W. (1999). "An early Cambrian craniate-like chordate". Nature. 402 (6761): 518–22. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..518C. doi:10.1038/990080. S2CID 24895681.

- ^ Shu, D.-G.; Conway Morris, S.; Han, J.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Yasui, K.; Janvier, P.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.-L.; Liu, J.-N.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.-Q. (January 2003). "Head and backbone of the Early Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys". Nature. 421 (6922): 526–529. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..526S. doi:10.1038/nature01264. PMID 12556891. S2CID 4401274.

- ^ Udroiu, I.; Sgura, A. (2017). "The phylogeny of the spleen". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 92 (4): 411–443. doi:10.1086/695327.

- ^ Elliot D.G. (2011) Functional Morphology of the Integumentary System in Fishes. In: Farrell A.P., (ed.), Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology: From Genome to Environment, volume 1, pp. 476–488. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 9780080923239.

- ^ These first vertebrates lacked jaws, like the living hagfish and lampreys. Jawed vertebrates appeared 100 million years later, in the Silurian. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/vertebrates/vertintro.html Berkeley University

- ^ A fossil coelacanth jaw found in a stratum datable 410 mya that was collected near Buchan in Victoria, Australia's East Gippsland, currently holds the record for oldest coelacanth; it was given the name Eoactinistia foreyi when it was published in September 2006. [1]

- ^ "Lungfish are believed to be the closest living relatives of the tetrapods, and share a number of important characteristics with them. Among these characters are tooth enamel, separation of pulmonary blood flow from body blood flow, arrangement of the skull bones, and the presence of four similarly sized limbs with the same position and structure as the four tetrapod legs." http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/vertebrates/sarco/dipnoi.html Berkeley University

- ^ "the ancestor that amphibians share with reptiles and ourselves?" "These possibly transitional fossils have been much studied, among them Acanthostega, which seems to have been wholly aquatic, and Ichthyostega" Richard Dawkins 2004 The Ancestor's Tale p. 250, ISBN 0-618-00583-8

- ^ Eckhart, L.; Valle, L. D.; Jaeger, K.; Ballaun, C.; Szabo, S.; Nardi, A.; Buchberger, M.; Hermann, M.; Alibardi, L.; Tschachler, E. (10 November 2008). "Identification of reptilian genes encoding hair keratin-like proteins suggests a new scenario for the evolutionary origin of hair". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (47): 18419–18423. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805154105. PMC 2587626. PMID 19001262.

- ^ http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/synapsids/pelycosaurs.html Berkeley University

- ^ Richard Dawkins 2004 The Ancestor's Tale p. 211, ISBN 0-618-00583-8

- ^ Werneburg, Ingmar; Spiekman, Stephan N F (2018). 4. Mammalian embryology and organogenesis. In: Zachos, Frank; Asher, Robert. Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 59-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110341553-004

- ^ "Fossils that might help us reconstruct what Concestor 8 was like include the large group called plesiadapi-forms. They lived about the right time, and they have many of the qualities you would expect of the grand ancestor of all the primates" Richard Dawkins 2004 The Ancestor's Tale p. 136, ISBN 0-618-00583-8

- ^ Renne, Paul R.; Deino, Alan L.; Hilgen, Frederik J.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mark, Darren F.; Mitchell, William S.; Morgan, Leah E.; Mundil, Roland; Smit, Jan (7 February 2013). "Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary". Science. 339 (6120): 684–87. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274.

- ^ "Paleontologists discover most primitive primate skeleton", Phys.org (January 23, 2007).

- ^ Alan de Queiroz, The Monkey's Voyage, Basic Books, 2014. ISBN 9780465020515

- ^ "A new primate species at the root of the tree of extant hominoids". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ Raauma, Ryan; Sternera, K (2005). "Catarrhine primate divergence dates estimated from complete mitochondrial genomes" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 48 (3): 237–57. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.11.007. PMID 15737392.

- ^ Böhme, Madelaine; Spassov, Nikolai; Fuss, Jochen; Tröscher, Adrian; Deane, Andrew S.; Prieto, Jérôme; Kirscher, Uwe; Lechner, Thomas; Begun, David R. (November 2019). "A new Miocene ape and locomotion in the ancestor of great apes and humans". Nature. 575 (7783): 489–493. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..489B. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1731-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31695194. S2CID 207888156.

- ^ Popadin, Konstantin; Gunbin, Konstantin; Peshkin, Leonid; Annis, Sofia; Fleischmann, Zoe; Kraytsberg, Genya; Markuzon, Natalya; Ackermann, Rebecca R.; Khrapko, Konstantin (2017-10-19). "Mitochondrial pseudogenes suggest repeated inter-species hybridization in hominid evolution". bioRxiv 134502. doi:10.1101/134502. hdl:11427/36660.

- ^ Perlman, David (July 12, 2001). "Fossils From Ethiopia May Be Earliest Human Ancestor". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2001.

Another co-author is Tim D. White, a paleoanthropologist at UC-Berkeley who in 1994 discovered a pre-human fossil, named Ardipithecus ramidus, that was then the oldest known, at 4.4 million years.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Asfaw, Berhane; Beyene, Yonas; Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Lovejoy, C. Owen; Suwa, Gen; WoldeGabriel, Giday (2009). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the Paleobiology of Early Hominids". Science. 326 (5949): 75–86. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...75W. doi:10.1126/science.1175802. PMID 19810190. S2CID 20189444.

- ^ Harmand, Sonia; Lewis, Jason E.; Feibel, Craig S.; Lepre, Christopher J.; Prat, Sandrine; Lenoble, Arnaud; Boës, Xavier; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Brenet, Michel; Arroyo, Adrian; Taylor, Nicholas; Clément, Sophie; Daver, Guillaume; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Leakey, Louise; Mortlock, Richard A.; Wright, James D.; Lokorodi, Sammy; Kirwa, Christopher; Kent, Dennis V.; Roche, Hélène (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–15. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Wilkinson, David M. (2011-12-27). "Avoidance of overheating and selection for both hair loss and bipedality in hominins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (52): 20965–20969. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820965R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113915108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3248486. PMID 22160694.

- ^ Villmoare, B.; Kimbel, W. H.; Seyoum, C.; et al. (2015). "Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- ^ Zhu, Zhaoyu; Dennell, Robin; Huang, Weiwen; Wu, Yi; Qiu, Shifan; Yang, Shixia; Rao, Zhiguo; Hou, Yamei; Xie, Jiubing; Han, Jiangwei; Ouyang, Tingping (2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–12. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. PMID 29995848. S2CID 49670311.

- ^ NOVA: Becoming Human Part 2 [2][dead link]

- ^ Jablonski, Nina G. (October 2004). "The Evolution of Human Skin and Skin Color". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33 (1): 585–623. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143955. S2CID 53481281.

- ^ Bermudez de Castro, J. M. (30 May 1997). "A Hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: Possible Ancestor to Neandertals and Modern Humans". Science. 276 (5317): 1392–1395. doi:10.1126/science.276.5317.1392. PMID 9162001.

- ^ Green, Richard E.; Krause, Johannes; Ptak, Susan E.; Briggs, Adrian W.; Ronan, Michael T.; Simons, Jan F.; Du, Lei; Egholm, Michael; Rothberg, Jonathan M.; Paunovic, Maja; Pääbo, Svante (November 2006). "Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA". Nature. 444 (7117): 330–336. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..330G. doi:10.1038/nature05336. PMID 17108958. S2CID 4320907.

- ^ "Rubin also said analysis so far suggests human and Neanderthal DNA are some 99.5 percent to nearly 99.9 percent identical." Neanderthal bone gives DNA clues (URL accessed on November 16, 2006)

- ^ "The conclusion is the old saw that we share 98.5% of our DNA sequence with chimpanzee is probably in error. For this sample, a better estimate would be that 95% of the base pairs are exactly shared between chimpanzee and human DNA." Britten, R.J. (2002). "Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels". PNAS. 99 (21): 13633–35. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913633B. doi:10.1073/pnas.172510699. PMC 129726. PMID 12368483.

- ^ "...of the three billion letters that make up the human genome, only 15 million—less than 1 percent—have changed in the six million years or so since the human and chimp lineages diverged." Pollard, K.S. (2009). "What makes us human?". Scientific American. 300–5 (5): 44–49. Bibcode:2009SciAm.300e..44P. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0509-44. PMID 19438048. S2CID 38866839.

- ^ Krause J, Lalueza-Fox C, Orlando L, Enard W, Green RE, Burbano HA, Hublin JJ, Hänni C, Fortea J, de la Rasilla M, Bertranpetit J, Rosas A, Pääbo S (November 2007). "The derived FOXP2 variant of modern humans was shared with Neandertals". Curr. Biol. 17 (21): 1908–12. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.1908K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.008. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-000F-FED3-1. PMID 17949978. S2CID 9518208.

- Nicholas Wade (October 19, 2007). "Neanderthals Had Important Speech Gene, DNA Evidence Shows". The New York Times.

- ^ Stein, Richard A. (October 2015). "Copy Number Analysis Starts to Add Up". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 35 (17): 20, 22–23. doi:10.1089/gen.35.17.09.

- ^ Meyer, Matthias; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; De Filippo, Cesare; Nagel, Sarah; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Nickel, Birgit; Martínez, Ignacio; Gracia, Ana; De Castro, José María Bermúdez; Carbonell, Eudald; Viola, Bence; Kelso, Janet; Prüfer, Kay; Pääbo, Svante (March 2016). "Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins". Nature. 531 (7595): 504–07. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..504M. doi:10.1038/nature17405. PMID 26976447. S2CID 4467094.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (2016). "Oldest ancient-human DNA details dawn of Neanderthals". Nature. 531 (7594): 296–86. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..296C. doi:10.1038/531286a. PMID 26983523. S2CID 4459329.

- ^ Mietto, Paolo; Avanzini, Marco; Rolandi, Giuseppe (2003). "Palaeontology: Human footprints in Pleistocene volcanic ash". Nature. 422 (6928): 133. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..133M. doi:10.1038/422133a. PMID 12634773. S2CID 2396763.

- ^ Timmermann, A.; Yun, KS.; Raia, P.; et al. (2022). "Climate effects on archaic human habitats and species successions". Nature. 604: 495–501. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04600-9. PMC 9021022.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114.

- ^ Tryon, Christopher A.; Faith, Tyler (2013). "Variability in the Middle Stone Age of Eastern Africa" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 54 (8): 234–54. doi:10.1086/673752. S2CID 14124486.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (10 July 2019). "A Skull Bone Discovered in Greece May Alter the Story of Human Prehistory - The bone, found in a cave, is the oldest modern human fossil ever discovered in Europe. It hints that humans began leaving Africa far earlier than once thought". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Staff (10 July 2019). "'Oldest remains' outside Africa reset human migration clock". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Harvati, Katerina; et al. (10 July 2019). "Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia". Nature. 571 (7766): 500–504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z. hdl:10072/397334. PMID 31292546. S2CID 195873640.

- ^ Heinz, Tanja; Pala, Maria; Gómez-Carballa, Alberto; Richards, Martin B.; Salas, Antonio (March 2017). "Updating the African human mitochondrial DNA tree: Relevance to forensic and population genetics". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 27: 156–159. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.12.016. PMID 28086175.

- ^ Poznik, G. D.; Henn, B. M.; Yee, M.-C.; Sliwerska, E.; Euskirchen, G. M.; Lin, A. A.; Snyder, M.; Quintana-Murci, L.; Kidd, J. M.; Underhill, P. A.; Bustamante, C. D. (1 August 2013). "Sequencing Y Chromosomes Resolves Discrepancy in Time to Common Ancestor of Males Versus Females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–565. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..562P. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239.

- ^ Karmin, Monika; Saag, Lauri; Vicente, Mário; Sayres, Melissa A. Wilson; Järve, Mari; Talas, Ulvi Gerst; Rootsi, Siiri; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Mägi, Reedik; Mitt, Mario; Pagani, Luca; Puurand, Tarmo; Faltyskova, Zuzana; Clemente, Florian; Cardona, Alexia; Metspalu, Ene; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Hudjashov, Georgi; DeGiorgio, Michael; Loogväli, Eva-Liis; Eichstaedt, Christina; Eelmets, Mikk; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Tambets, Kristiina; Litvinov, Sergei; Mormina, Maru; Xue, Yali; Ayub, Qasim; et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Clark, J. Desmond; Beyene, Yonas; WoldeGabriel, Giday; Hart, William K.; Renne, Paul R.; Gilbert, Henry; Defleur, Alban; Suwa, Gen; Katoh, Shigehiro; Ludwig, Kenneth R.; Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Asfaw, Berhane; White, Tim D. (June 2003). "Stratigraphic, chronological and behavioural contexts of Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 747–752. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..747C. doi:10.1038/nature01670. PMID 12802333. S2CID 4312418.

- ^ Scerri, Eleanor (2017). "The Stone Age Archaeology of West Africa". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.137. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4.

- ^ Henshilwood, C.S. and B. Dubreuil 2009. Reading the artifacts: gleaning language skills from the Middle Stone Age in southern Africa. In R. Botha and C. Knight (eds), The Cradle of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 41-61. ISBN 9780191567674.

- ^ Bowler JM, Johnston H, Olley JM, Prescott JR, Roberts RG, Shawcross W, Spooner NA (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia". Nature. 421 (6925): 837–40. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..837B. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511. S2CID 4365526.

- ^ Richard E. Green; Krause, J.; Briggs, A.W.; Maricic, T.; Stenzel, U.; Kircher, M.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; et al. (2010). "A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–22. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (2010-05-06). "Neanderthal genes 'survive in us'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Sankararaman, Sriram; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (2016). "The Combined Landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal Ancestry in Present-Day Humans". Current Biology. 26 (9): 1241–1247. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.1241S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.037. PMC 4864120. PMID 27032491.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (26 July 2012). "Hunter-gatherer genomes a trove of genetic diversity". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11076. S2CID 87081207.

- ^ Lachance, Joseph; Vernot, Benjamin; Elbers, Clara C.; Ferwerda, Bart; Froment, Alain; Bodo, Jean-Marie; Lema, Godfrey; Fu, Wenqing; Nyambo, Thomas B.; Rebbeck, Timothy R.; Zhang, Kun; Akey, Joshua M.; Tishkoff, Sarah A. (August 2012). "Evolutionary History and Adaptation from High-Coverage Whole-Genome Sequences of Diverse African Hunter-Gatherers". Cell. 150 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009. PMC 3426505. PMID 22840920.

- ^ Xu, Duo; Pavlidis, Pavlos; Taskent, Recep Ozgur; Alachiotis, Nikolaos; Flanagan, Colin; DeGiorgio, Michael; Blekhman, Ran; Ruhl, Stefan; Gokcumen, Omer (October 2017). "Archaic Hominin Introgression in Africa Contributes to Functional Salivary MUC7 Genetic Variation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (10): 2704–2715. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx206. PMC 5850612. PMID 28957509.

- ^ Mondal, Mayukh; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Lao, Oscar (16 January 2019). "Approximate Bayesian computation with deep learning supports a third archaic introgression in Asia and Oceania". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 246. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..246M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08089-7. PMC 6335398. PMID 30651539.

- ^ Klein, Richard (1995). "Anatomy, behavior, and modern human origins". Journal of World Prehistory. 9 (2): 167–98. doi:10.1007/bf02221838. S2CID 10402296.

- ^ Sutikna, Thomas; Tocheri, Matthew W.; Morwood, Michael J.; Saptomo, E. Wahyu; Jatmiko; Awe, Rokus Due; Wasisto, Sri; Westaway, Kira E.; Aubert, Maxime; Li, Bo; Zhao, Jian-xin; Storey, Michael; Alloway, Brent V.; Morley, Mike W.; Meijer, Hanneke J.M.; van den Bergh, Gerrit D.; Grün, Rainer; Dosseto, Anthony; Brumm, Adam; Jungers, William L.; Roberts, Richard G. (30 March 2016). "Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–69. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..366S. doi:10.1038/nature17179. PMID 27027286. S2CID 4469009.

- ^ Belezal, Sandra; Santos, A.M.; McEvoy, B.; Alves, I.; Martinho, C.; Cameron, E.; Shriver, M.D.; Parra, E.J.; Rocha, J. (2012). "The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207. PMC 3525146. PMID 22923467.

- ^ Fumagalli, M.; Moltke, I.; Grarup, N.; Racimo, F.; Bjerregaard, P.; Jorgensen, M. E.; Korneliussen, T. S.; Gerbault, P.; Skotte, L.; Linneberg, A.; Christensen, C.; Brandslund, I.; Jorgensen, T.; Huerta-Sanchez, E.; Schmidt, E. B.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T.; Albrechtsen, A.; Nielsen, R. (17 September 2015). "Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation". Science. 349 (6254): 1343–1347. Bibcode:2015Sci...349.1343F. doi:10.1126/science.aab2319. hdl:10044/1/43212. PMID 26383953. S2CID 546365.

- ^ Peng, Yi; Shi, Hong; Qi, Xue-bin; Xiao, Chun-jie; Zhong, Hua; Ma, Run-lin Z; Su, Bing (2010). "The ADH1B Arg47His polymorphism in East Asian populations and expansion of rice domestication in history". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 15. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10...15P. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-15. PMC 2823730. PMID 20089146.

- ^ Ségurel, Laure; Bon, Céline (31 August 2017). "On the Evolution of Lactase Persistence in Humans". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 18 (1): 297–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035340. PMID 28426286.

- ^ Ingram, Catherine J. E.; Mulcare, Charlotte A.; Itan, Yuval; Thomas, Mark G.; Swallow, Dallas M. (26 November 2008). "Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence". Human Genetics. 124 (6): 579–591. doi:10.1007/s00439-008-0593-6. PMID 19034520. S2CID 3329285.

- ^ Stibel, Jeffrey M. (August 2025). "Did increasing brain size place early humans at risk of extinction?". Brain and Cognition. 188 106336. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2025.106336. ISSN 0278-2626.

External links

[edit]- Mankind Rising on YouTube. From Curiosity documentary series

- Palaeos

- Berkeley Evolution

- History of Animal Evolution Archived 2016-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Tree of Life Web Project – explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).