Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Combined oral contraceptive pill

View on Wikipedia

| Combined oral contraceptive pill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background | |

| Type | Hormonal |

| First use | 1960 (United States) |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.3%[1] |

| Typical use | 9%[1] |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | 1–4 days |

| Reversibility | Yes |

| User reminders | Taken within same 24-hour window each day |

| Clinic review | 6 months |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Periods | Regulated, and often lighter and less painful |

| Weight | No proven effect |

| Benefits | Evidence for reduced mortality risk and reduced death rates in all cancers.[2] Possible reduced ovarian and endometrial cancer risks.[3][citation needed] May treat acne, PCOS, PMDD, endometriosis[citation needed] |

| Risks | Increase in some cancers.[4][5] Increase in DVTs; stroke,[6] cardiovascular disease[7] |

| Medical notes | |

| Affected by the antibiotic rifampicin,[8] the herb Hypericum (St John's wort) and some anti-epileptics, also vomiting or diarrhea. Caution if history of migraines. | |

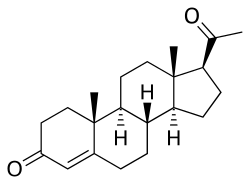

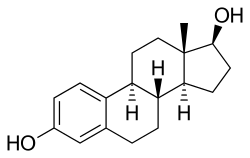

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. It is the oral form of combined hormonal contraception. The pill contains two important hormones: a progestin (a synthetic form of the hormone progestogen/progesterone) and estrogen (usually ethinylestradiol or 17β estradiol).[9][10][11][12] When taken correctly, it alters the menstrual cycle to eliminate ovulation and prevent pregnancy.

Combined oral contraceptive pills were first approved for contraceptive use in the United States in 1960, and remain a very popular form of birth control. They are used by more than 100 million women worldwide [13][14] including about 9 million women in the United States.[15][16] From 2015 to 2017, 12.6% of women aged 15–49 in the US reported using combined oral contraceptive pills, making it the second most common method of contraception in this age range (female sterilization is the most common method).[17] Use of combined oral contraceptive pills, however, varies widely by country,[18] age, education, and marital status. For example, one third of women aged 16–49 in the United Kingdom use either the combined pill or progestogen-only pill (POP),[19][20] compared with less than 3% of women in Japan (as of 1950–2014).[21]

Combined oral contraceptives are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[22] The pill was a catalyst for the sexual revolution.[23]

Background

[edit]Oral contraceptives

[edit]

Hormonal oral contraceptives are preventive medications taken orally by females to avoid pregnancy by manipulating their sex hormones. The first oral contraceptive was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and sold to the market in 1960. There are two types of hormonal oral contraceptives, namely Combined Oral Contraceptives and Progesterone Only Pills. Oral contraceptives, be it combined or progesterone-only, can effectively prevent pregnancy by regulating hormonal changes in the menstrual cycle, inhibiting ovulation, and altering cervical mucus to impede sperm mobility; combined pills have extra effects in menstrual cycle regulation and menstrual pain relief. Common off-label uses include menstrual suppression and acne relief, with Combined Oral Contraceptives having additional benefits in relieving menstrual migraine.

Variants

[edit]Progesterone-only pills (POPs) utilise progestin, the synthetic form of progesterone, as the only active pharmaceutical ingredient in the formulation.[24][25] In the US, drospirenone and norethindrone are the most commonly used compounds in formulations.[26]

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) are commonly classified into generations, referring to their order of development in history.[27] This discussion may also help identify some key features in a variety of products. According to EMA, the first generation of combined oral contraceptives, which made use of a high concentration of oestrogen only, were those invented in the 1960s.[27] In the second generation of products, progestogens were introduced into the formulation while the concentration of oestrogen was reduced.[27] Starting from the 1990s, the progression in the development of combined oral contraceptives has been directed towards varying the type of progestogen incorporated.[27] These products are referred as the third and fourth generation.[27]

Oestrogen ingredients: estradiol, ethinylestradiol, estetrol.[24]

1st generation progestin: norethindrone acetate, ethynodiol diacetate, lynestrenol, norethynodrel.[24]

2nd generation progestin: levonorgestrel, dl-norgestrel.[24]

3rd generation progestin: norgestimate, gestodene, desogestrel.[24]

The menstrual cycle

[edit]

Hormonal oral contraceptives (HOCs) interact with hormonal changes in the menstrual cycle in females to prevent ovulation, and hence achieve contraception.[24] In a 28-day menstrual cycle, there are the proliferative phase, ovulation, and then the secretory phase.[28]

Menstruation marks the beginning of proliferative phase in day 1-14.[28] In this period, the pituitary gland located near the brain secretes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) into the bloodstream to signal the development of follicle in ovary in the female reproductive system.[28] While follicle serves as the chamber of ovum development, it secretes Oestrogen, a hormone that not only triggers the thickening of uterine lining in preparation for implantation, but also inhibits the secretion of FSH in pituitary via a negative feedback mechanism.[28]

Specifically in ovulation, transient positive feedback by Oestrogen on FSH and Luteinising Hormone (LH) secretion from pituitary is permitted so that the release of mature ovum from follicle is triggered.[28]

In secretory phase on day 14-28, this follicle then transforms into corpus luteum and continues releasing Oestrogen with Progesterone into bloodstream.[28] While Oestrogen and Progesterone primarily aid the maintenance of thickness in uterine lining,[28] the negative feedback in pituitary allows them to inhibit FSH and LH secretion.[28] In the absence of LH, corpus luteum degenerates and ultimately causes blood Oestrogen and Progesterone levels to decline.[28] Without these thickness maintaining agents, uterine lining breaks down and hence the presentation of menstruation.[28]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Progesterone and Oestrogen, either in combination or with Progesterone-only, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients found in a hormonal oral contraceptive formulation.[29] These medications are orally administered for systemic absorption to exert their effects.[29] An artificially enhanced level of Progesterone throughout the menstrual cycle inhibits the pituitary secretion of FSH and LH such that their actions in stimulating follicular development and ovulation are prevented.[24] Similarly, a boosted Oestrogen level activates the negative feedback mechanism in reducing FSH secretion from pituitary and therefore prevents follicular development.[24] In the absence of a developed follicle, ovulation cannot occur so that fertilisation is made impossible and contraception is achieved.[29] In comparison, Progesterone is more efficacious than Oestrogen not only because of its additional action in impeding LH, but also its ability to modulate the cervical mucus into sperm-repellent.[24]

Combined oral contraceptive pills were developed to prevent ovulation by suppressing the release of gonadotropins. Combined hormonal contraceptives, including combined oral contraceptive pills, inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation as a primary mechanism of action.[30][31][32][33]

Under normal circumstances, luteinizing hormone (LH) stimulates the theca cells of the ovarian follicle to produce androstenedione. The granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle then convert this androstenedione to estradiol. This conversion process is catalyzed by aromatase, an enzyme produced as a result of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation.[34] In individuals using oral contraceptives, progestogen negative feedback decreases the pulse frequency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by the hypothalamus, which decreases the secretion of FSH and greatly decreases the secretion of LH by the anterior pituitary. Decreased levels of FSH inhibit follicular development, preventing an increase in estradiol levels. Progestogen negative feedback and the lack of estrogen positive feedback on LH secretion prevent a mid-cycle LH surge. Inhibition of follicular development and the absence of an LH surge prevent ovulation.[30][31][32]

Estrogen was originally included in oral contraceptives for better cycle control (to stabilize the endometrium and thereby reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding), but was also found to inhibit follicular development and help prevent ovulation. Estrogen negative feedback on the anterior pituitary greatly decreases the secretion of FSH, which inhibits follicular development and helps prevent ovulation.[30][31][32]

Another primary mechanism of action of all progestogen-containing contraceptives is inhibition of sperm penetration through the cervix into the upper genital tract (uterus and fallopian tubes) by decreasing the water content and increasing the viscosity of the cervical mucus.[30]

The estrogen and progestogen in combined oral contraceptive pills have other effects on the reproductive system, but these have not been shown to contribute to their contraceptive efficacy:[30]

- Slowing tubal motility and ova transport, which may interfere with fertilization.

- Endometrial atrophy and alteration of metalloproteinase content, which may impede sperm motility and viability, or theoretically inhibit implantation.

- Endometrial edema, which may affect implantation.

Insufficient evidence exists on whether changes in the endometrium could actually prevent implantation. The primary mechanisms of action are so effective that the possibility of fertilization during combined oral contraceptive pill use is very small. Since pregnancy occurs despite endometrial changes when the primary mechanisms of action fail, endometrial changes are unlikely to play a significant role, if any, in the observed effectiveness of combined oral contraceptive pills.[30]

Formulations

[edit]Oral contraceptives come in a variety of formulations, some containing both estrogen and progestins, and some only containing progestin. Doses of component hormones also vary among products, and some pills are monophasic (delivering the same dose of hormones each day) while others are multiphasic (doses vary each day). combined oral contraceptive pills can also be divided into two groups, those with progestins that possess androgen activity (norethisterone acetate, etynodiol diacetate, levonorgestrel, norgestrel, norgestimate, desogestrel, gestodene) or antiandrogen activity (cyproterone acetate, chlormadinone acetate, drospirenone, dienogest, nomegestrol acetate).

Combined oral contraceptive pills have been somewhat inconsistently grouped into "generations" in the medical literature based on when they were introduced.[35][36]

- First generation combined oral contraceptive pills are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins noretynodrel, norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, or etynodiol acetate;[35] and sometimes defined as all combined oral contraceptive pills containing ≥ 50 μg ethinylestradiol.[36]

- Second generation combined oral contraceptive pills are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins norgestrel or levonorgestrel;[35] and sometimes defined as those containing the progestins norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, etynodiol acetate, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, or norgestimate and < 50 μg ethinylestradiol.[36]

- Third generation combined oral contraceptive pills are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins desogestrel or gestodene;[36] and sometimes defined as those containing desogestrel, gestodene, or norgestimate.[35]

- Fourth generation combined oral contraceptive pills are sometimes defined as those containing the progestin drospirenone;[35] and sometimes defined as those containing drospirenone, dienogest, or nomegestrol acetate.[36]

Medical use

[edit]

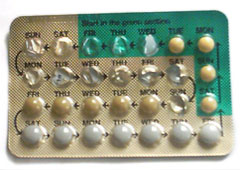

Contraceptive use

[edit]Combined oral contraceptive pills are a type of oral medication that were originally designed to be taken every day at the same time of day in order to prevent pregnancy.[26][37] There are many different formulations or brands, but the average pack is designed to be taken over a 28-day period (also known as a cycle).[citation needed] For the first 21 days of the cycle, users take a daily pill that contains two hormones, estrogen and progestogen.[citation needed] During the last 7 days of the cycle, users take daily placebo (biologically inactive) pills and these days are considered hormone-free days.[citation needed] Although these are hormone-free days, users are still protected from pregnancy during this time.[medical citation needed]

Some combined oral contraceptive pill packs only contain 21 pills and users are advised to take no pills for the last 7 days of the cycle.[9] Other combined oral contraceptive pill formulations contain 91 pills, consisting of 84 days of active hormones followed by 7 days of placebo (Seasonale).[26] Combined oral contraceptive pill formulations can contain 24 days of active hormone pills followed by 4 days of placebo pills (e.g. Yaz 28 and Loestrin 24 Fe) as a means to decrease the severity of placebo effects.[9] These combined oral contraceptive pills containing active hormones and a placebo/hormone-free period are called cyclic combined oral contraceptive pills. Once a pack of cyclical combined oral contraceptive pill treatment is completed, users start a new pack and new cycle.[38]

Most monophasic combined oral contraceptive pills can be used continuously such that patients can skip placebo days and continuously take hormone active pills from a combined oral contraceptive pill pack.[9] One of the most common reasons users do this is to avoid or diminish withdrawal bleeding. The majority of women on cyclic combined oral contraceptive pills have regularly scheduled withdrawal bleeding, which is vaginal bleeding mimicking users' menstrual cycles with the exception of lighter menstrual bleeding compared to bleeding patterns prior to combined oral contraceptive pill commencement. As such, a study reported that out of 1003 women taking combined oral contraceptive pills approximately 90% reported regularly scheduled withdrawal bleeds over a 90-day standard reference period.[9] Withdrawal bleeding usually occurs during the placebo, hormone-free days.[medical citation needed] Therefore, avoiding placebo days can diminish withdrawal bleeding among other placebo effects.[medical citation needed]

Regimen

[edit]This section demonstrates the overall rationalisation of dosing route and intervals of hormonal oral contraceptives, please seek advice and follow instructions from healthcare professionals in administering specific hormonal oral contraceptives. Considering the menstrual cycle as a 28-day cycle, hormonal oral contraceptives are available in packages of 21, 28, or 91 tablets.[29] These pills have typically undergone unit dose optimisation so that they follow the administration pattern of once daily, every day or almost every day on a regular basis.[29] Since they are formulated into daily doses, it is recommended that the medication should be taken at the same time every day to maximise efficacy.[29]

For 21-tablet packs, the general instruction is to take one tablet daily for 21 days, followed by a 7-day blank interval without taking hormonal oral contraceptives before initiating another 21-tablet pack.[29] For 28-tablet packs, the 1st tablet from a new pack should be taken on the next day when the 28th tablet from an old pack was finished.[29] While the 7-day blank period does not apply to 28-tablet packs, they will likely include tablets in distinctive colours indicating that they have an alternate amount of active ingredients, otherwise inactive ingredient or folate supplement only.[29] The instruction for 91-tablet pack follows that of 28-tablet packs with some colour-distinguishable tablets which contain different amounts of medicine or supplement.[29]

To acquire immediate contraceptive effects, the initiation of hormonal oral contraceptive dosing is recommended within the 1st-5th day from menstruation in order to discard other means of contraception.[39] Specific to Progesterone only pills, even if dosing is initiated within five days, backup contraception is suggested in the first 48 hours since the first pill.[24] In the case of dosing initiated after the 5th day from menstruation, effects usually take place after seven days and other contraceptive methods should remain in place until then.[39]

Effectiveness

[edit]If used exactly as instructed, the estimated risk of getting pregnant is 0.3% which means that about 3 in 1000 women on combined oral contraceptive pills will become pregnant within one year.[40] However, typical use of combined oral contraceptive pills by users often consists of timing errors, forgotten pills, or unwanted side effects. With typical use, the estimated risk of getting pregnant is about 9% which means that about 9 in 100 women on combined oral contraceptive pills will become pregnant in one year.[41] The perfect use failure rate is based on a review of pregnancy rates in clinical trials, and the typical use failure rate is based on a weighted average of estimates from the 1995 and 2002 US National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG), corrected for underreporting of abortions.[42][43]

Several factors account for typical use effectiveness being lower than perfect use effectiveness:

- Mistakes on part of those providing instructions on how to use the method

- Mistakes on part of the user

- Conscious user non-compliance with instructions

For instance, someone using combined oral contraceptive pills might have received incorrect information by a health care provider about medication frequency, forgotten to take the pill one day or not gone to the pharmacy in time to renew a combined oral contraceptive pill prescription.

Combined oral contraceptive pills provide effective contraception from the very first pill if started within five days of the beginning of the menstrual cycle (within five days of the first day of menstruation). If started at any other time in the menstrual cycle, combined oral contraceptive pills provide effective contraception only after 7 consecutive days of use of active pills, so a backup method of contraception (e.g. condoms) must be used in the interim.[44][45]

The effectiveness of combined oral contraceptive pills appears to be similar whether the active pills are taken continuously or if they are taken cyclically.[46] Contraceptive efficacy, however, could be impaired by numerous means. Factors that may contribute to a decrease in effectiveness:[44]

- Missing more than one active pill in a packet,

- Delay in starting the next packet of active pills (i.e., extending the pill-free, inactive pill or placebo pill period beyond 7 days),

- Intestinal malabsorption of active pills due to vomiting or diarrhea,

- Drug-drug interactions among combined oral contraceptive pills and other medications of the user that decrease contraceptive estrogen and/or progestogen levels.[44]

In any of these instances, a backup contraceptive method should be used until hormone active pills have been consistently taken for 7 consecutive days or drug-drug interactions or underlying illnesses have been discontinued or resolved.[44] According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, a pill is considered "late" if a user takes the pill after the user's normal medication time, but no longer than 24 hours after this normal time. If 24 hours or more have passed since the time the user was supposed to take the pill, then the pill is considered "missed".[40] CDC guidelines discuss potential next steps for users who missed their pill or took it late.[47]

Role of placebo pills

[edit]The role of the placebo pills is two-fold: to allow the user to continue the routine of taking a pill every day and to simulate the average menstrual cycle. By continuing to take a pill every day, users remain in the daily habit even during the week without hormones. Failure to take pills during the placebo week does not impact the effectiveness of the pill, provided that daily ingestion of active pills is resumed at the end of the week.[48]

The placebo, or hormone-free, week in the 28-day pill package simulates an average menstrual cycle, though the hormonal events during a pill cycle are significantly different from those of a normal ovulatory menstrual cycle. Because the pill suppresses ovulation (to be discussed more in the Mechanism of action section), birth control users do not have true menstrual periods. Instead, it is the lack of hormones for a week that causes a withdrawal bleed.[37] The withdrawal bleeding that occurs during the break from active pills has been thought to be reassuring, a physical confirmation of not being pregnant.[49] The withdrawal bleeding is also predictable. Unexpected breakthrough bleeding can be a possible side effect of longer term active regimens.[50]

Since it is not uncommon for menstruating women to become anemic, some placebo pills may contain an iron supplement.[51][52] This replenishes iron stores that may become depleted during menstruation. As well, birth control pills, such as combined oral contraceptive pills, are sometimes fortified with folic acid as it is recommended to take folic acid supplementation in the months prior to pregnancy to decrease the likelihood of neural tube defect in infants.[53][54]

No or less frequent placebos

[edit]If the pill formulation is monophasic, meaning each hormonal pill contains a fixed dose of hormones, it is possible to skip withdrawal bleeding and still remain protected against conception by skipping the placebo pills altogether and starting directly with the next packet. Attempting this with bi- or tri-phasic pill formulations carries an increased risk of breakthrough bleeding and may be undesirable. It will not, however, increase the risk of getting pregnant.

Starting in 2003, women have also been able to use a three-month version of the pill.[55] Similar to the effect of using a constant-dosage formulation and skipping the placebo weeks for three months, Seasonale gives the benefit of less frequent periods, at the potential drawback of breakthrough bleeding. Seasonique is another version in which the placebo week every three months is replaced with a week of low-dose estrogen.

A version of the combined pill has also been packaged to eliminate placebo pills and withdrawal bleeds. Marketed as Anya or Lybrel, studies have shown that after seven months, 71% of users no longer had any breakthrough bleeding, the most common side effect of going longer periods of time without breaks from active pills.

While more research needs to be done to assess the long term safety of using combined oral contraceptive pills continuously, studies have shown there may be no difference in short term adverse effects when comparing continuous use versus cyclic use of birth control pills.[46]

Non-contraceptive use

[edit]The hormones in the pill have also been used to treat other medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, acne, hirsutism, amenorrhea, menstrual cramps, menstrual migraines, menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding), menstruation-related or fibroid-related anemia and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation).[41][56] Besides acne, no oral contraceptives have been approved by the US FDA for the previously mentioned uses despite extensive use for these conditions.[57]

PCOS

[edit]The cause of PCOS, or polycystic ovary syndrome, is multifactorial and not well-understood. Women with PCOS often have higher than normal levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and androgens that impact the normal function of the ovaries.[58] While multiple small follicles develop in the ovary, none are able to grow in size enough to become the dominant follicle and trigger ovulation.[59] This leads to an imbalance of LH, follicle stimulating hormone, estrogen, and progesterone. Without ovulation, unopposed estrogen can lead to endometrial hyperplasia, or overgrowth of tissue in the uterus.[60] This endometrial overgrowth is more likely to become cancerous than normal endometrial tissue.[61] Thus, although the data varies, it is generally agreed upon by most gynecological societies that due to the unopposed estrogen, women with PCOS are at higher risk for endometrial cancer.[62]

To reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, it is often recommended that women with PCOS who do not desire pregnancy take hormonal contraceptives to prevent the effects of unopposed estrogen. Both combined oral contraceptive pills and progestin-only methods are recommended.[citation needed] It is the progestin component of combined oral contraceptive pills that protects the endometrium from hyperplasia, and thus reduces a woman with PCOS's endometrial cancer risk.[63] Combined oral contraceptive pills are preferred to progestin-only methods in women who also have uncontrolled acne, symptoms of hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia, because combined oral contraceptive pills can help treat these symptoms.[37]

Acne and hirsutism

[edit]Combined oral contraceptive pills are sometimes prescribed to treat symptoms of androgenization, including acne and hirsutism.[64] The estrogen component of combined oral contraceptive pills appears to suppress androgen production in the ovaries. Estrogen also leads to increased synthesis of sex hormone binding globulin, which causes a decrease in the levels of free testosterone.[65]

Ultimately, the drop in the level of free androgens leads to a decrease in the production of sebum, which is a major contributor to development of acne.[citation needed] Four different oral contraceptives have been approved by the US FDA to treat moderate acne if the patient is at least 14 or 15 years old, has already begun menstruating, and needs contraception. These include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, Estrostep, Beyaz, and YAZ.[66][67][68]

Hirsutism is the growth of coarse, dark hair where women typically grow only fine hair or no hair at all.[69] This hair growth on the face, chest, and abdomen is also mediated by higher levels or action of androgens. Therefore, combined oral contraceptive pills also work to treat these symptoms by lowering the levels of free circulating androgens.[70]

Studies have shown that combined oral contraceptives are effective in reducing both inflammatory and non-inflammatory facial acne lesions.[71] However, comparisons between different combined oral contraceptives have not been studied to understand if any brand is superior than the others.[71] Oestrogen decreases sebum production by shrinking the sebaceous gland, increasing Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) production to reduce unbound testosterone, and regulating LH and FSH levels.[72] Studies have not shown that POPs are effective against acne lesions.[citation needed]

Endometriosis

[edit]For pelvic pain associated with endometriosis, combined oral contraceptive pills are considered a first-line medical treatment, along with NSAIDs, GnRH agonists, and aromatase inhibitors.[73] Combined oral contraceptive pills work to suppress the growth of the extra-uterine endometrial tissue. This works to lessen its inflammatory effects.[37] Combined oral contraceptive pills, along with the other medical treatments listed above, do not eliminate the extra-uterine tissue growth, they just reduce the symptoms. Surgery is the only definitive treatment. Studies looking at rates of pelvic pain recurrence after surgery have shown that continuous use of combined oral contraceptive pills is more effective at reducing the recurrence of pain than cyclic use.[74]

Adenomyosis

[edit]Similar to endometriosis, adenomyosis is often treated with combined oral contraceptive pills to suppress the growth the endometrial tissue that has grown into the myometrium. Unlike endometriosis however, levonorgestrel containing IUDs are more effective at reducing pelvic pain in adenomyosis than combined oral contraceptive pills.[37]

Menorrhagia

[edit]In the average menstrual cycle, a woman typically loses 35 to 40 milliliters of blood.[75] However, up to 20% of women experience much heavier bleeding, or menorrhagia.[76] This excess blood loss can lead to anemia, with symptoms of fatigue and weakness, as well as disruption in their normal life activities.[77] Combined oral contraceptive pills contain progestin, which causes the lining of the uterus to be thinner, resulting in lighter bleeding episodes for those with heavy menstrual bleeding.[78]

Amenorrhea

[edit]Although the pill is sometimes prescribed to induce menstruation on a regular schedule for women bothered by irregular menstrual cycles, it actually suppresses the normal menstrual cycle and then mimics a regular 28-day monthly cycle.

Women who are experiencing menstrual dysfunction due to female athlete triad are sometimes prescribed oral contraceptives as pills that can create menstrual bleeding cycles.[79] However, the condition's underlying cause is energy deficiency and should be treated by correcting the imbalance between calories eaten and calories burned by exercise. Oral contraceptives should not be used as an initial treatment for female athlete triad.[79]

Menstrual suppression

[edit]Menstrual bleeding is not necessary in women who do not wish to conceive, therefore menstrual suppression may be implemented in women who do not want to have menstrual bleeding for convenience, gynecologic disorders, bleeding disorders or other medical conditions.[80]

In the two types of hormonal oral contraceptives, only combined oral contraceptives can achieve amenorrhea, while POPs can only reduce the amount of blood.[81] The method of using combined oral contraceptives for menstrual suppression is to skip the 7 placebo pills and continue taking active pills after the 21 active pills.[82] This can be used in extended method or continuous method.[82] For extended method, patients who take active pills for 3, 4, or 6 months and then take placebo pills for a period of time will more likely experience withdrawal bleeding.[82] The interval can be decided by the patients according to their own preferences.[82] For continuous method, people can take combined oral contraceptives for a year continuously without any placebo pills.[82] In the first few months of extended or continuous use of combined oral contraceptives, unscheduled bleeding or spotting may occur.[83] However, the bleeding or spotting is expected to resolve after a few months of use.[83]

Menstrual suppression is commonly used for convenience especially when women go on vacation.[80] It is also used for gynecologic disorders such as dysmenorrhea (commonly known as menstrual pain), symptoms related to premenstrual hormone change and excessive bleeding related to uterine fibroids. Patients can also benefit from menstrual suppression for bleeding disorders or chronic anemia.[80]

Menstrual migraine

[edit]Patients with menstrual Oestrogen-related migraine, but without aura and additional risk factors to stroke, can be benefited from combined oral contraceptives.[84][85] However, older women and those with a strong family history of problematic headaches may find that using hormonal oral contraceptives worsens their headache.[84][85]

Benefits

[edit]The distinctive feature of hormonal oral contraceptives when compared to other contraceptive methods is that they are less invasive and do not interfere with sex.[39] Conclusive data suggest that the failure rate of contraception in using hormonal oral contraceptives for the first year is 9% in typical use which allows missed doses, and <1% in perfect use.[24][39] The efficacy of hormonal oral contraceptives in preventing pregnancy is high overall.[24] Furthermore, the regular use of hormonal oral contraceptive tends to not only ease premenstrual syndrome, but also allow lighter and less painful menstruation.[39] In addition, the association between a suppressed risk of developing ovarian cancer and hormonal oral contraceptive use is proven.[86][87]

Contraindications

[edit]While combined oral contraceptives are generally considered to be a relatively safe medication, they are contraindicated for those with certain medical conditions. The World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publish guidance, called medical eligibility criteria, on the safety of birth control in the context of medical conditions.[88][41]

In terms of protection in sexual intercourse, a sole reliance on hormonal oral contraceptives does not defend one from sexually transmitted infections such as HPV.[24][39] Additionally, breakthrough bleeding and spotting are exceptionally prevalent in the early stage of using hormonal oral contraceptives.[24][29][39] Although most reported side effects including nausea, headache, or mood swings will disappear as the therapy progresses or upon switching formulation, elevated blood pressure or blood clots in patients with cardiovascular conditions are documented side effects that requires medical attention if not termination of hormonal oral contraceptives.[24][29][39] It is because combined oral contraceptives uses have been found to be related to an increased risk of ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction, especially in combined oral contraceptives with >50 μg Oestrogen.[89] Besides, some ongoing studies giving evidence on the association between hormonal oral contraceptive use and escalated breast cancer risks cannot be neglected.[90][91][86][87]

According to WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2015, Category 3 implies that the use of such contraception is usually not recommended, unless other more appropriate methods are neither available nor acceptable and with good resources of clinical judgment; Category 4 implies that the contraceptive method should not be used even with good resources of clinical judgment.[92] Both categories suggest that the contraceptive method should not be used with limited resources for clinical judgment.[92] The tables below summarise conditions of category 3 and 4 from World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2015.

Precautions and contraindications for combined oral contraceptives

[edit]| Condition | Category |

|---|---|

| Breastfeeding | |

| for < 6 weeks postpartum | 4 |

| for ≥ 6 weeks to < 6 months postpartum | 3 |

| Postpartum (non-breastfeeding) | |

| < 21 days postpartum without other risk factors for VTE | 3 |

| < 21 days postpartum with other risk factors for VTE | 4 |

| ≥ 21 days to 42 days postpartum with other risk factors for VTE | 3 |

| Smoking | |

| age ≥ 35 years and smoking < 15 cigarettes/day | 3 |

| age ≥ 35 years and smoking ≥ 15 cigarettes/day | 4 |

| Multiple risk factors for arterial cardiovascular disease | 3/4* |

| Hypertension | |

| history of hypertension, where blood pressure CANNOT be evaluated | 3 |

| adequately controlled hypertension, where blood pressure CAN be evaluated | 3 |

| elevated blood pressure levels (properly taken measurements)

with systolic 140–159 or diastolic 90–99 mm Hg |

3 |

| elevated blood pressure levels (properly taken measurements)

with systolic ≥ 160 or diastolic ≥ 100 mm Hg |

4 |

| elevated blood pressure levels (properly taken measurements) with Vascular disease | 4 |

| Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) / Pulmonary embolism (PE) | |

| with History of DVT/PE | 4 |

| with acute DVT/PE | 4 |

| with DVT/PE and established on anticoagulant therapy | 4 |

| with Major surgery with prolonged immobilization | 4 |

| Known thrombogenic mutations | 4 |

| Current and history of ischemic heart disease | 4 |

| Stroke (history of cerebrovascular accident) | 4 |

| Complicated valvular heart disease | 4 |

| Positive (or unknown) antiphospholipid antibodies Systemic Lupus Erythematous | 4 |

| Headache | |

| migraine without aura of age ≥ 35 years (for initiation of combined oral contraceptives) | 3 |

| migraine without aura of age < 35 years (for continuation of combined oral contraceptives) | 3 |

| migraine without aura of age ≥ 35 years (for continuation of combined oral contraceptives) | 4 |

| migraine with aura, at any age (for initiation and continuation of combined oral contraceptives) | 4 |

| Breast cancer | |

| current Breast cancer | 4 |

| past Breast Cancer and no evidence of current disease for 5 years | 3 |

| Nephropathy/retinopathy/neuropathy | 3/4* |

| Other vascular disease or diabetes of > 20 years' duration | 3/4* |

| Medically treated symptomatic gall bladder disease | 3 |

| Current symptomatic gall bladder disease | 3 |

| Past-combined oral contraceptive related history of Cholestasis | 3 |

| Acute or flare viral hepatitis (for initiation of combined oral contraceptives) | 3/4* |

| Severe cirrhosis (decompensated) | 4 |

| Liver tumors | |

| hepatocellular adenoma | 4 |

| malignant (hepatoma) | 4 |

| On anticonvulsant therapy | |

| with phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, topiramate, oxcarbazepine | 3 |

| with Lamotrigine | 3 |

| On antimicrobial therapy with Rifampicin or rifabutin therapy | |

*The category should be assessed according to the severity of the condition.

Hypercoagulability

[edit]Estrogen in high doses can increase risk of blood clots. All combined oral contraceptive pill users have a small increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism compared with non-users; this risk is greatest within the first year of combined oral contraceptive pill use.[93] Individuals with any pre-existing medical condition that also increases their risk for blood clots have a more significant increase in risk of thrombotic events with combined oral contraceptive pill use.[93] These conditions include but are not limited to high blood pressure, pre-existing cardiovascular disease (such as valvular heart disease or ischemic heart disease[94]), history of thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular accident, and a familial tendency to form blood clots (such as familial factor V Leiden).[95] There are conditions that, when associated with combined oral contraceptive pill use, increase risk of adverse effects other than thrombosis. For example, women with a history of migraine with aura have an increased risk of stroke when using combined oral contraceptive pills, and women who smoke over age 35 and use combined oral contraceptive pills are at higher risk of myocardial infarction.[88]

Pregnancy and postpartum

[edit]Women who are known to be pregnant should not take combined oral contraceptive pills. Those in the postpartum period who are breastfeeding are also advised not to start combined oral contraceptive pills until 4 weeks after birth due to increased risk of blood clots.[40] While studies have demonstrated conflicting results about the effects of combined oral contraceptive pills on lactation duration and milk volume, there exist concerns about the transient risk of combined oral contraceptive pills on breast milk production when breastfeeding is being established early postpartum.[96] Due to the stated risks and additional concerns on lactation, women who are breastfeeding are not advised to start combined oral contraceptive pills until at least six weeks postpartum, while women who are not breastfeeding and have no other risks factors for blood clots may start combined oral contraceptive pills after 21 days postpartum.[97][88]

Breast cancer

[edit]The World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend the use of combined oral contraceptive pills in women with breast cancer.[41][98] Since combined oral contraceptive pills contain both estrogen and progestin, they are not recommended to be used in those with hormonally-sensitive cancers, including some types of breast cancer.[99][unreliable medical source?][100] Non-hormonal contraceptive methods, such as the Copper IUD or condoms,[101] should be the first-line contraceptive choice for these patients instead of combined oral contraceptive pills.[102][unreliable medical source?]

Other

[edit]Women with known or suspected endometrial cancer or unexplained uterine bleeding should also not take combined oral contraceptive pills to avoid health risks.[94] Combined oral contraceptive pills are also contraindicated for people with advanced diabetes, liver tumors, hepatic adenoma or severe cirrhosis of the liver.[41][95] Combined oral contraceptive pills are metabolized in the liver and thus liver disease can lead to reduced elimination of the medication. Additionally, severe hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia are also contraindications, but the evidence showing that combined oral contraceptive pills lead to worse outcomes in this population is weak.[37][40] Obesity is not considered to be a contraindication to taking combined oral contraceptive pills.[40]

Side effects

[edit]It is generally accepted that the health risks of oral contraceptives are lower than those from pregnancy and birth,[103] and "the health benefits of any method of contraception are far greater than any risks from the method".[104] Some organizations have argued that comparing a contraceptive method to no method (pregnancy) is not relevant—instead, the comparison of safety should be among available methods of contraception.[105]

Common

[edit]Different sources note different incidence of side effects. The most common side effect is breakthrough bleeding. Combined oral contraceptive pills can improve conditions such as dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and acne,[106] reduce symptoms of endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome, and decrease the risk of anemia.[107] Use of oral contraceptives also reduces lifetime risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer.[108][109][110]

Nausea, vomiting, headache, bloating, breast tenderness, swelling of the ankles/feet (fluid retention), or weight change may occur. Vaginal bleeding between periods (spotting) or missed/irregular periods may occur, especially during the first few months of use.[111]

Heart and blood vessels

[edit]Combined oral contraceptives are associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).[112][113]

While lower doses of estrogen in combined oral contraceptive pills may have a lower risk of stroke and myocardial infarction compared to higher estrogen dose pills (50 μg/day), users of low estrogen dose combined oral contraceptive pills still have an increased risk compared to non-users.[114] These risks are greatest in women with additional risk factors, such as smoking (which increases risk substantially) and long-continued use of the pill, especially in women over 35 years of age.[115]

The overall absolute risk of venous thrombosis per 100,000 woman-years in current use of combined oral contraceptives is approximately 60, compared with 30 in non-users.[116] The risk of thromboembolism varies with different types of birth control pills; compared with combined oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel (LNG), and with the same dose of estrogen and duration of use, the rate ratio of deep venous thrombosis for combined oral contraceptives with norethisterone is 0.98, with norgestimate 1.19, with desogestrel (DSG) 1.82, with gestodene 1.86, with drospirenone (DRSP) 1.64, and with cyproterone acetate 1.88.[116] In comparison, venous thromboembolism occurs in 100–200 per 100.000 pregnant women every year.[116]

One study showed more than a 600% increased risk of blood clots for women taking combined oral contraceptive pills with drospirenone compared with non-users, compared with 360% higher for women taking birth control pills containing levonorgestrel.[117] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated studies evaluating the health of more than 800,000 women taking combined oral contraceptive pills and found that the risk of VTE was 93% higher for women who had been taking drospirenone combined oral contraceptive pills for 3 months or less and 290% higher for women taking drospirenone combined oral contraceptive pills for 7–12 months, compared with women taking other types of oral contraceptives.[118]

Based on these studies, in 2012, the FDA updated the label for drospirenone combined oral contraceptive pills to include a warning that contraceptives with drospirenone may have a higher risk of dangerous blood clots.[119]

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis found that combined birth control pills were associated with 7.6-fold higher risk of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, a rare form of stroke in which blood clotting occurs in the cerebral venous sinuses.[120]

| Type | Route | Medications | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal hormone therapy | Oral | Estradiol alone ≤1 mg/day >1 mg/day |

1.27 (1.16–1.39)* 1.22 (1.09–1.37)* 1.35 (1.18–1.55)* |

| Conjugated estrogens alone ≤0.625 mg/day >0.625 mg/day |

1.49 (1.39–1.60)* 1.40 (1.28–1.53)* 1.71 (1.51–1.93)* | ||

| Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.44 (1.09–1.89)* | ||

| Estradiol/dydrogesterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.18 (0.98–1.42) 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | ||

| Estradiol/norethisterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.68 (1.57–1.80)* 1.38 (1.23–1.56)* 1.84 (1.69–2.00)* | ||

| Estradiol/norgestrel or estradiol/drospirenone | 1.42 (1.00–2.03) | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 2.10 (1.92–2.31)* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/norgestrel ≤0.625 mg/day CEEs >0.625 mg/day CEEs |

1.73 (1.57–1.91)* 1.53 (1.36–1.72)* 2.38 (1.99–2.85)* | ||

| Tibolone alone | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | ||

| Raloxifene alone | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | ||

| Transdermal | Estradiol alone ≤50 μg/day >50 μg/day |

0.96 (0.88–1.04) 0.94 (0.85–1.03) 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Estradiol/progestogen | 0.88 (0.73–1.01) | ||

| Vaginal | Estradiol alone | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | |

| Conjugated estrogens alone | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | ||

| Combined birth control | Oral | Ethinylestradiol/norethisterone | 2.56 (2.15–3.06)* |

| Ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel | 2.38 (2.18–2.59)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/norgestimate | 2.53 (2.17–2.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/desogestrel | 4.28 (3.66–5.01)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/gestodene | 3.64 (3.00–4.43)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone | 4.12 (3.43–4.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate | 4.27 (3.57–5.11)* | ||

| Notes: (1) Nested case–control studies (2015, 2019) based on data from the QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) databases. (2) Bioidentical progesterone was not included, but is known to be associated with no additional risk relative to estrogen alone. Footnotes: * = Statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sources: See template. | |||

Cancer

[edit]Decreased risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancers

[edit]Usage of combined oral concetraption decreased the risk of ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer,[44] and colorectal cancer.[4][106][121] Two large cohort studies published in 2010 both found a significant reduction in adjusted relative risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer mortality in ever-users of OCs compared with never-users.[2][122] The use of oral contraceptives (birth control pills) for five years or more decreases the risk of ovarian cancer in later life by 50%.[121][123] Combined oral contraceptive use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 40% and the risk of endometrial cancer by 50% compared with never users. The risk reduction increases with duration of use, with an 80% reduction in risk for both ovarian and endometrial cancer with use for more than 10 years. The risk reduction for both ovarian and endometrial cancer persists for at least 20 years.[44]

Increased risk of Breast, cervical, and liver cancers

[edit]Combined oral concetraption is a IARC group 1 Carcinogen meaning there is sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in humans.

An association between use of birth control pills and liver cancer has been suspected, but subsequent large population research has failed to confirm such an association.[124]

Increased risk of breast cancer was reported in women who take combined oral concetraption.[125][126] The relative risk of breast cancer in the current combined oral concetraption users was 1.24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–1.33), and this increased risk disappeared 10 years after discontinuation.[127] There was also a higher risk of premature deaths due to breast cancer in the population who used COCP (P < 0.0001) for longer duration.[128] 24 observational studies showed a higher risk of cervical cancer in women who use COCP, especially with an increased duration of COCP use.[129][126]

A 2013 meta-analysis concluded that every use of birth control pills is associated with a modest increase in the risk of breast cancer (relative risk 1.08) and a reduced risk of colorectal cancer (relative risk 0.86) and endometrial cancer (relative risk 0.57). Cervical cancer risk in those infected with HPV is increased.[130] A similar small increase in breast cancer risk was observed in other meta analyses.[131][132] A study of 1.8 million Danish women of reproductive age followed for 11 years found that the risk of breast cancer was 20% higher among those who currently or recently used hormonal contraceptives than among women who had never used hormonal contraceptives.[133] This risk increased with duration of use, with a 38% increase in risk after more than 10 years of use.[133]

Weight

[edit]A 2016 systematic review found low quality evidence that studies of combination hormonal contraceptives showed no large difference in weight when compared with placebo or no intervention groups.[134] The evidence was not strong enough to be certain that contraceptive methods do not cause some weight change, but no major effect was found.[134] This review also found "that women did not stop using the pill or patch because of weight change".[134]

Sexual function and risk aversion

[edit]Sexual desire

[edit]Some researchers question a causal link between combined oral contraceptive pill use and decreased libido;[135] a 2007 study of 1700 women found combined oral contraceptive pill users experienced no change in sexual satisfaction.[136] A 2005 laboratory study of genital arousal tested fourteen women before and after they began taking combined oral contraceptive pills. The study found that women experienced a significantly wider range of arousal responses after beginning pill use; decreases and increases in measures of arousal were equally common.[137][138]

In 2012, The Journal of Sexual Medicine published a review of research studying the effects of hormonal contraceptives on female sexual function that concluded that the sexual side effects of hormonal contraceptives are not well-studied and especially in regards to impacts on libido, with research establishing only mixed effects where only small percentages of women report experiencing an increase or decrease and majorities report being unaffected.[139] In 2013, The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care published a review of 36 studies including 8,422 female subjects in total taking combined oral contraceptive pills that found that 5,358 subjects (or 63.6 percent) reported no change in libido, 1,826 subjects (or 21.7 percent) reported an increase, and 1,238 subjects (or 14.7 percent) reported a decrease.[140] In 2019, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews published a meta-analysis of 22 published and 4 unpublished studies (with 7,529 female subjects in total) that evaluated whether women expose themselves to greater health risks at different points in the menstrual cycle including by sexual activity with partners and found that subjects in the last third of the follicular phase and at ovulation (when levels of endogenous estradiol and luteinizing hormones are heightened) experienced increased sexual activity with partners as compared with the luteal phase and during menstruation.[141]

A 2006 study of 124 premenopausal women measured sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), including before and after discontinuation of the oral contraceptive pill. Women continuing use of oral contraceptives had SHBG levels four times higher than those who never used it, and levels remained elevated even in the group that had discontinued its use.[142][143] Theoretically, an increase in SHBG may be a physiologic response to increased hormone levels, but may decrease the free levels of other hormones, such as androgens, because of the unspecificity of its sex hormone binding. In 2020, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology published a cross-sectional study of 588 premenopausal female subjects aged 18 to 39 years from the Australian states of Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria with regular menstrual cycles whose SHBG levels were measured by immunoassay that found that after controlling for age, body mass index, cycle stage, smoking, parity, partner status, and psychoactive medication, SHBG was inversely correlated with sexual desire.[144]

Sexual attractiveness and function

[edit]Combined oral contraceptive pills may increase natural vaginal lubrication,[145] while some women experience decreased lubrication.[145][146]

In 2004, the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences published a study where pairs of digital photographs of the faces of 48 women at Newcastle University and Charles University between the ages 19 and 33 who were not taking hormonal contraceptives during the study were photographed in the late follicular and early mid-luteal phases of their menstrual cycles and the photographs were then rated by 261 blinded subjects (130 male and 131 female) at their respective universities who compared the facial attractiveness of each photographed woman in their photograph pairs, and found that the subjects perceived the late follicular phase images of the photographed women as being more attractive than the luteal phase images by more than expected by random chance.[147]

In 2007, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study where 18 professional lap dancers recorded their menstrual cycles, work shifts, and tip earnings at gentlemen's clubs for 60 days that found by a mixed model analysis of 296 work shifts (or approximately 5,300 lap dances) that the 11 dancers with normal menstrual cycles earned US$335 per 5-hour shift during the late follicular phase and at ovulation, US$260 per shift during the luteal phase, and US$185 per shift during menstruation, while the 7 dancers using hormonal contraceptives showed no earnings peak during the late follicular phase and at ovulation.[148] In 2008, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study where the voices of 51 female students at the State University of New York at Albany were recorded with the women counting from 1 to 10 at four different points in their menstrual cycles were rated by blinded subjects who listened to the recordings to be more attractive at the points of the menstrual cycle with higher probabilities of conception, while the ratings of the voices of the women who were taking hormonal contraceptives showed no variation over the menstrual cycle in attractiveness.[149]

Risk-taking behaviour

[edit]In 1998, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study of 300 female undergraduate students at the State University of New York at Albany between the ages of 18 and 54 (with a mean age of 21.9 years) that surveyed the subjects engagement in 18 different behaviors over the 24 hours prior to filling out the study's questionnaire that varied in their risk of potential rape or sexual assault and the first day of their last menstruations, and found that subjects at ovulation showed statistically significant decreased engagement in behaviors that risked rape and sexual assault while subjects taking birth control pills showed no variation over their menstrual cycles in the same behaviors (suggesting a psychologically adaptive function of the hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle in causing avoidance of behaviors that risk rape and sexual assault).[150][151] In 2003, Evolution and Human Behavior published a conceptual replication study of the 1998 survey that confirmed its findings.[152]

In 2006, a study presented at the annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society surveyed 176 female undergraduate students at Michigan State University (with a mean age of 19.9 years) in a decision-making experiment where the subjects chose between an option with a guaranteed outcome or an option involving risk and indicated the first day of their last menstruations, and found that the subjects risk aversion preferences varied over the menstrual cycle (with none of the subjects at ovulation preferring the risky option) and only subjects not taking hormonal contraceptives showed the menstrual cycle effect on risk aversion.[153] In the 2019 Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews meta-analysis, the research reviewed also evaluated whether the 7,529 female subjects across the 26 studies showed greater risk recognition and avoidance of potentially threatening people and dangerous situations at different phases of the menstrual cycle and found that the subjects displayed better risk accuracy recognition during the late follicular phase and at ovulation as compared to the luteal phase.[141]

Depression

[edit]Low levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter in the brain, have been linked to depression. High levels of estrogen, as in first-generation combined oral contraceptive pills, and progestin, as in some progestin-only contraceptives, have been shown to lower the brain serotonin levels by increasing the concentration of a brain enzyme that reduces serotonin.[citation needed]

Current medical reference textbooks on contraception[44] and major organizations such as the American ACOG,[154] the WHO,[88] and the United Kingdom's RCOG[155] agree that current evidence indicates low-dose combined oral contraceptives are unlikely to increase the risk of depression, and unlikely to worsen the condition in women that are depressed.

Hypertension

[edit]Bradykinin lowers blood pressure by causing blood vessel dilation. Certain enzymes are capable of breaking down bradykinin (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, Aminopeptidase P). Progesterone can increase the levels of Aminopeptidase P (AP-P), thereby increasing the breakdown of bradykinin, which increases the risk of developing hypertension.[156]

Thyroid

[edit]Estrogen in oral contraceptives may increase thyroid binding globulin and decrease free T4. Thus, longer history of oral contraceptives use may be strongly associated with hypothyroidism, especially for more than 10 years. Also, a higher dose of thyroxine may be needed with oral contraceptives.[157]

Other effects

[edit]Other side effects associated with low-dose combined oral contraceptive pills are leukorrhea (increased vaginal secretions), reductions in menstrual flow, mastalgia (breast tenderness), and decrease in acne. Side effects associated with older high-dose combined oral contraceptive pills include nausea, vomiting, increases in blood pressure, and melasma (facial skin discoloration); these effects are not strongly associated with low-dose formulations.[medical citation needed]

Excess estrogen, such as from birth control pills, appears to increase cholesterol levels in bile and decrease gallbladder movement, which can lead to gallstones.[158] Progestins found in certain formulations of oral contraceptive pills can limit the effectiveness of weight training to increase muscle mass.[159] This effect is caused by the ability of some progestins to inhibit androgen receptors. One study claims that the pill may affect what male body odors a woman prefers, which may in turn influence her selection of partner.[160][161][162] Use of combined oral contraceptives is associated with a reduced risk of endometriosis, giving a relative risk of endometriosis of 0.63 during active use, yet with limited quality of evidence according to a systematic review.[163]

Combined oral contraception decreases total testosterone levels by approximately 0.5 nmol/L, free testosterone by approximately 60%, and increases the amount of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) by approximately 100 nmol/L. Contraceptives containing second generation progestins and/or estrogen doses of around 20 –25 mg EE were found to have less impact on SHBG concentrations.[164] Combined oral contraception may also reduce bone density.[165]

Drug interactions

[edit]Some drugs reduce the effect of the pill and can cause breakthrough bleeding, or increased chance of pregnancy. These include drugs such as rifampicin, barbiturates, phenytoin and carbamazepine. In addition cautions are given about broad spectrum antibiotics, such as ampicillin and doxycycline, which may cause problems "by impairing the bacterial flora responsible for recycling ethinylestradiol from the large bowel" (BNF 2003).[166][167][168][169]

The traditional medicinal herb St John's Wort has also been implicated due to its upregulation of the P450 system in the liver which could increase the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and progestin components of some combined oral contraception.[170]

Accessibility

[edit]The availability of pharmaceutical products to the public is determined by the local governing body. In the US, the responsible organisation is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). According to a press announcement in July 2023, a daily hormonal oral contraceptive was first made accessible to the public without a prescription.[171] Although this drug class was approved for prescription use as early as in 1973, it took an additional 50 years to de-escalate its legal status. Such allowance is made plausible thanks to the demonstration of its safe and effective use by the general public, not needing any guidance from healthcare professionals.[171] Ultimately, the governing body should act accordingly to applicants' evidence and update the local legislation.[171]

History

[edit]By the 1930s, scientists had isolated and determined the structure of the steroid hormones and found that high doses of androgens, estrogens or progesterone inhibited ovulation,[179][180][181][182] but obtaining these hormones, which were produced from animal extracts, from European pharmaceutical companies was extraordinarily expensive.[183]

In 1939, Russell Marker, a professor of organic chemistry at Pennsylvania State University, developed a method of synthesizing progesterone from plant steroid sapogenins, initially using sarsapogenin from sarsaparilla, which proved too expensive. After three years of extensive botanical research, he discovered a much better starting material, the saponin from inedible Mexican yams (Dioscorea mexicana and Dioscorea composita) found in the rain forests of Veracruz near Orizaba. The saponin could be converted in the lab to its aglycone moiety diosgenin. Unable to interest his research sponsor Parke-Davis in the commercial potential of synthesizing progesterone from Mexican yams, Marker left Penn State and in 1944 co-founded Syntex with two partners in Mexico City. When he left Syntex a year later the trade of the barbasco yam had started and the period of the heyday of the Mexican steroid industry had been started. Syntex broke the monopoly of European pharmaceutical companies on steroid hormones, reducing the price of progesterone almost 200-fold over the next eight years.[184][185][186]

Midway through the 20th century, the stage was set for the development of a hormonal contraceptive, but pharmaceutical companies, universities and governments showed no interest in pursuing research.[187]

Progesterone to prevent ovulation

[edit]Progesterone, given by injections, was first shown to inhibit ovulation in animals in 1937 by Makepeace and colleagues.[188]

In 1951, reproductive physiologist Gregory Pincus, a leader in hormone research and co-founder of the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology (WFEB) in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, first met American birth control movement founder Margaret Sanger at a Manhattan dinner hosted by Abraham Stone, medical director and vice president of Planned Parenthood (PPFA), who helped Pincus obtain a small grant from PPFA to begin hormonal contraceptive research.[189][190][191] Research started in April 1951, with reproductive physiologist Min Chueh Chang repeating and extending the 1937 experiments of Makepeace et al. that was published in 1953 and showed that injections of progesterone suppressed ovulation in rabbits.[188] In October 1951, G. D. Searle & Company refused Pincus' request to fund his hormonal contraceptive research, but retained him as a consultant and continued to provide chemical compounds to evaluate.[183][192][193]

In March 1952, Sanger wrote a brief note mentioning Pincus' research to her longtime friend and supporter, suffragist and philanthropist Katharine Dexter McCormick, who visited the WFEB and its co-founder and old friend Hudson Hoagland in June 1952 to learn about contraceptive research there. Frustrated when research stalled from PPFA's lack of interest and meager funding, McCormick arranged a meeting at the WFEB in June 1953, with Sanger and Hoagland, where she first met Pincus who committed to dramatically expand and accelerate research with McCormick providing fifty times PPFA's previous funding.[192][194]

Pincus and McCormick enlisted Harvard clinical professor of gynecology John Rock, chief of gynecology at the Free Hospital for Women and an expert in the treatment of infertility, to lead clinical research with women. At a scientific conference in 1952, Pincus and Rock, who had known each other for many years, discovered they were using similar approaches to achieve opposite goals. In 1952, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudopregnancy" state in eighty of his infertility patients with continuous gradually increasing oral doses of an estrogen (5 to 30 mg/day diethylstilbestrol) and progesterone (50 to 300 mg/day), and within the following four months 15% of the women became pregnant.[192][195][196]

In 1953, at Pincus' suggestion, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudopregnancy" state in twenty-seven of his infertility patients with an oral 300 mg/day progesterone-only regimen for 20 days from cycle days 5–24 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding.[197] This produced the same 15% pregnancy rate during the following four months without the amenorrhea of the previous continuous estrogen and progesterone regimen.[197] But 20% of the women experienced breakthrough bleeding and in the first cycle ovulation was suppressed in only 85% of the women, indicating that even higher and more expensive oral doses of progesterone would be needed to initially consistently suppress ovulation.[197] Similarly, Ishikawa and colleagues found that ovulation inhibition occurred in only a "proportion" of cases with 300 mg/day oral progesterone.[198] Despite the incomplete inhibition of ovulation by oral progesterone, no pregnancies occurred in the two studies, although this could have simply been due to chance.[198][199] However, Ishikawa et al. reported that the cervical mucus in women taking oral progesterone became impenetrable to sperm, and this may have accounted for the absence of pregnancies.[198][199]

Progesterone was abandoned as an oral ovulation inhibitor following these clinical studies due to the high and expensive doses required, incomplete inhibition of ovulation, and the frequent incidence of breakthrough bleeding.[188][200] Instead, researchers would turn to much more potent synthetic progestogens for use in oral contraception in the future.[188][200]

Progestins to prevent ovulation

[edit]In October 1951, Chemist Luis Miramontes, working under the supervision of Carl Djerassi, and the direction of George Rosenkranz at Syntex in Mexico City, synthesized the first oral contraceptive, which was based on highly active progestin norethisterone. Frank B. Colton at Searle in Skokie, Illinois synthesized the orally highly active progestins noretynodrel (an isomer of norethisterone) in 1952 and norethandrolone in 1953.[183]

Pincus asked his contacts at pharmaceutical companies to send him chemical compounds with progestogenic activity. Chang screened nearly 200 chemical compounds in animals and found the three most promising were Syntex's norethisterone and Searle's noretynodrel and norethandrolone.[201]

In December 1954, Rock began the first studies of the ovulation-suppressing potential of 5–50 mg doses of the three oral progestins for three months (for 21 days per cycle—days 5–25 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding) in fifty of his patients with infertility in Brookline, Massachusetts. Norethisterone or noretynodrel 5 mg doses and all doses of norethandrolone suppressed ovulation but caused breakthrough bleeding, but 10 mg and higher doses of norethisterone or noretynodrel suppressed ovulation without breakthrough bleeding and led to a 14% pregnancy rate in the following five months. Pincus and Rock selected Searle's noretynodrel for the first contraceptive trials in women, citing its total lack of androgenicity versus Syntex's norethisterone very slight androgenicity in animal tests.[202][203]

Combined oral contraceptive

[edit]Noretynodrel (and norethisterone) were subsequently discovered to be contaminated with a small percentage of the estrogen mestranol (an intermediate in their synthesis), with the noretynodrel in Rock's 1954–5 study containing 4–7% mestranol. When further purifying noretynodrel to contain less than 1% mestranol led to breakthrough bleeding, it was decided to intentionally incorporate 2.2% mestranol, a percentage that was not associated with breakthrough bleeding, in the first contraceptive trials in women in 1954. The noretynodrel and mestranol combination was given the proprietary name Enovid.[203][204]

The first contraceptive trial of Enovid led by Celso-Ramón García and Edris Rice-Wray began in April 1956 in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico.[205][206][207] A second contraceptive trial of Enovid (and norethisterone) led by Edward T. Tyler began in June 1956 in Los Angeles.[186][208] In January 1957, Searle held a symposium reviewing gynecologic and contraceptive research on Enovid through 1956 and concluded Enovid's estrogen content could be reduced by 33% to lower the incidence of estrogenic gastrointestinal side effects without significantly increasing the incidence of breakthrough bleeding.[209]

While these large-scale trials contributed to the initial understanding of the pill formulation's clinical effects, the ethical implications of the trials generated significant controversy. Of note is the apparent lack of both autonomy and informed consent among participants in the Puerto Rican cohort prior to the trials. Many of these participants hailed from impoverished, working-class backgrounds.[10]

Public availability

[edit]As of 2013, less than a third of countries worldwide required a prescription for oral contraceptives.[210]

United States

[edit]

In June 1957, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Enovid 10 mg (9.85 mg noretynodrel and 150 μg mestranol) for menstrual disorders, based on data from its use by more than 600 women. Numerous additional contraceptive trials showed Enovid at 10, 5, and 2.5 mg doses to be highly effective. In July 1959, Searle filed a supplemental application to add contraception as an approved indication for 10, 5, and 2.5 mg doses of Enovid. The FDA refused to consider the application until Searle agreed to withdraw the lower dosage forms from the application. In May 1960, the FDA announced it would approve Enovid 10 mg for contraceptive use, and did so in June 1960. At that point, Enovid 10 mg had been in general use for three years and, by conservative estimate, at least half a million women had used it.[207][211][212]

Although FDA-approved for contraceptive use, Searle never marketed Enovid 10 mg as a contraceptive. Eight months later, in February 1961, the FDA approved Enovid 5 mg for contraceptive use. In July 1961, Searle finally began marketing Enovid 5 mg (5 mg noretynodrel and 75 μg mestranol) to physicians as a contraceptive.[211][213]

Although the FDA approved the first oral contraceptive in 1960, contraceptives were not available to married women in all states until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, and were not available to unmarried women in all states until Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972.[187][213]

The first published case report of a blood clot and pulmonary embolism in a woman using Enavid (Enovid 10 mg in the US) at a dose of 20 mg/day did not appear until November 1961, four years after its approval, by which time it had been used by over one million women.[207][214][215] It would take almost a decade of epidemiological studies to conclusively establish an increased risk of venous thrombosis in oral contraceptive users and an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in oral contraceptive users who smoke or have high blood pressure or other cardiovascular or cerebrovascular risk factors.[211] These risks of oral contraceptives were dramatized in the 1969 book The Doctors' Case Against the Pill by feminist journalist Barbara Seaman who helped arrange the 1970 Nelson Pill Hearings called by Senator Gaylord Nelson.[216] The hearings were conducted by senators who were all men and the witnesses in the first round of hearings were all men, leading Alice Wolfson and other feminists to protest the hearings and generate media attention.[213] Their work led to mandating the inclusion of patient package inserts with oral contraceptives to explain their possible side effects and risks to help facilitate informed consent.[217][218][219] Today's standard dose oral contraceptives contain an estrogen dose that is one third lower than the first marketed oral contraceptive and contain lower doses of different, more potent progestins in a variety of formulations.[44][211][213]

Beginning in 2015, certain states passed legislation allowing pharmacists to prescribe oral contraceptives. Such legislation was considered to address physician shortages and decrease barriers to birth control for women.[220] Pharmacists in Oregon, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maryland, and New Mexico have authority to prescribe birth control after receiving specialized training and certification from their respective state Board of Pharmacy.[221][222] As of January 2024[update], pharmacists in 29 states can prescribe oral contraceptives.[223]

A progestin-based birth control pill (Opill) was approved by the FDA in 2023 and is available over the counter.[224] Estrogen-based pills still require prescriptions as of 2024.

Australia

[edit]The first oral contraceptive introduced outside the United States was Schering's Anovlar (norethisterone acetate 4 mg + ethinylestradiol 50 μg) in January 1961, in Australia.[225]

Germany

[edit]The first oral contraceptive introduced in Europe was Schering's Anovlar in June 1961, in West Germany.[225] The lower hormonal dose, still in use, was studied by the Belgian Gynaecologist Ferdinand Peeters.[226][227]

United Kingdom

[edit]Before the mid-1960s, the United Kingdom did not require pre-marketing approval of drugs. The British Family Planning Association (FPA) through its clinics was then the primary provider of family planning services in the UK and provided only contraceptives that were on its Approved List of Contraceptives (established in 1934). In 1957, Searle began marketing Enavid (Enovid 10 mg in the US) for menstrual disorders. Also in 1957, the FPA established a Council for the Investigation of Fertility Control (CIFC) to test and monitor oral contraceptives which began animal testing of oral contraceptives and in 1960 and 1961 began three large clinical trials in Birmingham, Slough, and London.[207][228]

In March 1960, the Birmingham FPA began trials of noretynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 50 μg, but a high pregnancy rate initially occurred when the pills accidentally contained only 36 μg of mestranol—the trials were continued with noretynodrel 5 mg + mestranol 75 μg (Conovid in the UK, Enovid 5 mg in the US).[229] In August 1960, the Slough FPA began trials of noretynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 100 μg (Conovid-E in the UK, Enovid-E in the US).[230] In May 1961, the London FPA began trials of Schering's Anovlar.[231]

In October 1961, at the recommendation of the Medical Advisory Council of its CIFC, the FPA added Searle's Conovid to its Approved List of Contraceptives.[232] In December 1961, Enoch Powell, then Minister of Health, announced that the oral contraceptive pill Conovid could be prescribed through the NHS at a subsidized price of 2s per month.[233][234] In 1962, Schering's Anovlar and Searle's Conovid-E were added to the FPA's Approved List of Contraceptives.[207][230][231]

France

[edit]In December 1967, the Neuwirth Law legalized contraception in France, including the pill.[235] The pill is the most popular form of contraception in France, especially among young women. It accounts for 60% of the birth control used in France. The abortion rate has remained stable since the introduction of the pill.[236]

Japan