Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Endocrine disruptor

View on WikipediaThis article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (August 2019) |

Endocrine disruptors, sometimes also referred to as hormonally active agents,[1] endocrine disrupting chemicals,[2] or endocrine disrupting compounds[3] are chemicals that can interfere with endocrine (or hormonal) systems.[4] These disruptions can cause numerous adverse human health outcomes, including alterations in sperm quality and fertility; abnormalities in sex organs‚ endometriosis‚ early puberty‚ altered nervous system or immune function; certain cancers; respiratory problems; metabolic issues; diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular problems; growth, neurological and learning disabilities, and more.[5][6] Found in many household and industrial products, endocrine disruptors "interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones in the body that are responsible for development, behavior, fertility, and maintenance of homeostasis (normal cell metabolism)."[7][8][9]

Any system in the body controlled by hormones can be derailed by hormone disruptors. Specifically, endocrine disruptors may be associated with the development of learning disabilities, severe attention deficit disorder, and cognitive and brain development problems.[10][11][12][13]

There has been controversy over endocrine disruptors, with some groups calling for swift action by regulators to remove them from the market, and regulators and other scientists calling for further study.[14] Some endocrine disruptors have been identified and removed from the market (for example, a drug called diethylstilbestrol), but it is uncertain whether some endocrine disruptors on the market actually harm humans and wildlife at the doses to which wildlife and humans are exposed. The World Health Organization published a 2012 report stating that low-level exposures may cause adverse effects in humans.[15]

History

[edit]The term endocrine disruptor was coined in 1991 at the Wingspread Conference Center in Wisconsin. One of the early papers on the phenomenon was by Theo Colborn in 1993.[16] In this paper, she stated that environmental chemicals disrupt the development of the endocrine system, and that effects of exposure during development are often permanent. Although the endocrine disruption has been disputed by some,[17] work sessions from 1992 to 1999 have generated consensus statements from scientists regarding the hazard from endocrine disruptors, particularly in wildlife and also in humans.[18][19][20][21][22]

The Endocrine Society released a scientific statement outlining mechanisms and effects of endocrine disruptors on "male and female reproduction, breast development and cancer, prostate cancer, neuroendocrinology, thyroid, metabolism and obesity, and cardiovascular endocrinology," and showing how experimental and epidemiological studies converge with human clinical observations "to implicate endocrine disruptive chemicals (EDCs) as a significant concern to public health." The statement noted that it is difficult to show that endocrine disruptors cause human diseases, and it recommended that the precautionary principle should be followed.[23] A concurrent statement expresses policy concerns.[24]

Endocrine disrupting compounds encompass a variety of chemical classes, including drugs, pesticides, compounds used in the plastics industry and in consumer products, industrial by-products and pollutants, heavy metals and even some naturally produced botanical chemicals. Industrial chemicals such as parabens, phenols and phthalates are also considered potent endocrine disruptors.[25] Some are pervasive and widely dispersed in the environment and may bioaccumulate. Some are persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and can be transported long distances across national boundaries and have been found in virtually all regions of the world, and may even concentrate near the North Pole, due to weather patterns and cold conditions.[26] Others are rapidly degraded in the environment or human body or may be present for only short periods of time.[27] Health effects attributed to endocrine disrupting compounds include a range of reproductive problems (reduced fertility, male and female reproductive tract abnormalities, and skewed male/female sex ratios, loss of fetus, menstrual problems[28]); changes in hormone levels; early puberty; brain and behavior problems; impaired immune functions; and various cancers.[29]

One example of the consequences of the exposure of developing animals, including humans, to hormonally active agents is the case of the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES), a nonsteroidal estrogen and not an environmental pollutant. Prior to its ban in the early 1970s, doctors prescribed DES to as many as five million pregnant women to block spontaneous abortion, an off-label use of this medication prior to 1947. It was discovered after the children went through puberty that DES affected the development of the reproductive system and caused vaginal cancer. The relevance of the DES saga to the risks of exposure to endocrine disruptors is questionable, as the doses involved are much higher in these individuals than in those due to environmental exposures.[30]

Aquatic life subjected to endocrine disruptors in an urban effluent have experienced decreased levels of serotonin and increased feminization.[31]

In 2013 the WHO and the United Nations Environment Programme released a study, the most comprehensive report on EDCs to date, calling for more research to fully understand the associations between EDCs and the risks to health of human and animal life. The team pointed to wide gaps in knowledge and called for more research to obtain a fuller picture of the health and environmental impacts of endocrine disruptors. To improve global knowledge the team has recommended:

- Testing: known EDCs are only the 'tip of the iceberg' and more comprehensive testing methods are required to identify other possible endocrine disruptors, their sources, and routes of exposure.

- Research: more scientific evidence is needed to identify the effects of mixtures of EDCs on humans and wildlife (mainly from industrial by-products) to which humans and wildlife are increasingly exposed.

- Reporting: many sources of EDCs are not known because of insufficient reporting and information on chemicals in products, materials and goods.

- Collaboration: more data sharing between scientists and between countries can fill gaps in data, primarily in developing countries and emerging economies.[32]

Endocrine system

[edit]

Endocrine systems are found in most varieties of animals. The endocrine system consists of glands that secrete hormones, and receptors that detect and react to the hormones.[33]

Hormones travel throughout the body via the bloodstream and act as chemical messengers.[34] Hormones interface with cells that contain matching receptors in or on their surfaces. The hormone binds with the receptor, much like a key would fit into a lock. The endocrine system regulates adjustments through slower internal processes, using hormones as messengers. The endocrine system secretes hormones in response to environmental stimuli and to orchestrate developmental and reproductive changes. The adjustments brought on by the endocrine system are biochemical, changing the cell's internal and external chemistry to bring about a long term change in the body.[35] These systems work together to maintain the proper functioning of the body through its entire life cycle. Sex steroids such as estrogens and androgens, as well as thyroid hormones, are subject to feedback regulation, which tends to limit the sensitivity of these glands.[36]

Hormones work at very small doses (part per billion ranges).[37] Endocrine disruption can thereby also occur from low-dose exposure to exogenous hormones or hormonally active chemicals such as bisphenol A. These chemicals can bind to receptors for other hormonally mediated processes.[38] Furthermore, since endogenous hormones are already present in the body in biologically active concentrations, additional exposure to relatively small amounts of exogenous hormonally active substances can disrupt the proper functioning of the body's endocrine system. Thus, an endocrine disruptor can elicit adverse effects at much lower doses than a toxicity, acting through a different mechanism.

The timing of exposure is also critical. Most critical stages of development occur in utero, where the fertilized egg divides, rapidly developing every structure of a fully formed baby, including much of the wiring in the brain. Interfering with the hormonal communication in utero can have profound effects both structurally and toward brain development. Depending on the stage of reproductive development, interference with hormonal signaling can result in irreversible effects not seen in adults exposed to the same dose for the same length of time.[39][40][41] Experiments with animals have identified critical developmental time points in utero and days after birth when exposure to chemicals that interfere with or mimic hormones have adverse effects that persist into adulthood.[40][42][43][44] Disruption of thyroid function early in development may be the cause of abnormal sexual development in both males[45] and females[46] early motor development impairment,[47] and learning disabilities.[48]

There are studies of cell cultures, laboratory animals, wildlife, and accidentally exposed humans that show that environmental chemicals cause a wide range of reproductive, developmental, growth, and behavior effects, and so while "endocrine disruption in humans by pollutant chemicals remains largely undemonstrated, the underlying science is sound and the potential for such effects is real."[49] While compounds that produce estrogenic, androgenic, antiandrogenic, and antithyroid actions have been studied, less is known about interactions with other hormones.

The interrelationships between exposures to chemicals and health effects are rather complex. It is hard to definitively link a particular chemical with a specific health effect, and exposed adults may not show any ill effects. But, fetuses and embryos, whose growth and development are highly controlled by the endocrine system, are more vulnerable to exposure and may develop overt or subtle lifelong health or reproductive abnormalities.[50] Prebirth exposure, in some cases, can lead to permanent alterations and adult diseases.[51]

Some in the scientific community are concerned that exposure to endocrine disruptors in the womb or early in life may be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders including reduced IQ, ADHD, and autism.[52] Certain cancers and uterine abnormalities in women are associated with exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in the womb due to DES used as a medical treatment.

In a 2005 publication, phthalates in pregnant women's urine was linked to subtle, but specific, genital changes in their male infants—a shorter, more female-like anogenital distance and associated incomplete descent of testes and a smaller scrotum and penis.[53] The science behind this study was questioned by phthalate industry consultants,[54] and back in 2008, there were only five studies of anogenital distance in humans,[55] with one researcher stating, "Whether AGD measures in humans relate to clinically important outcomes, however, remains to be determined, as does its utility as a measure of androgen action in epidemiological studies."[56] Today, it is well-established that AGD is an indicator of fetal androgen exposure, and several studies have found a correlation between AGD and the incidence of prostate cancer.[57][58]

Effects on intrinsic hormones

[edit]Toxicology research shows that some endocrine disruptors target the specific hormone trait that allows one hormone to regulate the production or degradation of intrinsic hormones.[59][60] As endocrine disruptors have the potential to mimic or antagonize natural hormones, these chemicals can exert their effects by acting through interaction with nuclear receptors, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor or membrane bound receptors.[61][62]

U-shaped dose-response curve

[edit]Most toxicants, including endocrine disruptors, have been claimed to follow a U-shaped dose-response curve.[63] This means that very low and very high levels have more effects than mid-level exposure to a toxicant.[64]

Endocrine-disrupting effects have been noted in animals exposed to environmentally relevant levels of some chemicals. For example, a common flame retardant, BDE-47, affects the reproductive system and thyroid gland of female rats in doses similar to which humans are exposed.[65]

Low concentrations of endocrine disruptors can also have synergistic effects in amphibians, but it is not clear that this is an effect mediated through the endocrine system.[66]

A consensus statement by the Learning and Developmental Disabilities Initiative argued that "The very low-dose effects of endocrine disruptors cannot be predicted from high-dose studies, which contradicts the standard 'dose makes the poison' rule of toxicology. Nontraditional dose-response curves are referred to as non-monotonic dose response curves."[52]

It has been claimed that tamoxifen and some phthalates have fundamentally different (and harmful) effects on the body at low doses than at high doses.[67]

Routes of exposure

[edit]

Food

[edit]Food is a major mechanism by which people are exposed to pollutants. Diet is thought to account for up to 90% of a person's PCB and DDT body burden.[68] In a study of 32 different common food products from three grocery stores in Dallas, Texas, fish and other animal products were found to be contaminated with PBDE.[69] Since these compounds are fat-soluble, it is likely they are accumulating from the environment in the fatty tissue of animals eaten by humans. Some suspect fish consumption is a major source of many environmental contaminants. Indeed, both wild and farmed salmon from all over the world have been shown to contain a variety of man-made organic compounds.[70] While pesticides are found in many food products, phthalates can also leech into crops, vegetables and fruits from contaminated soil and greenhouse plastic covers.[71]

Endocrine disruptors can lead to hormonal changes in the body. Children and infants are more at risk of being affected by these chemicals. Phthalates (PAE) are used to make plastics last longer, and these plastics can be found in water bottles or in all dairy production stages.[72] Drinking water from plastic water bottles is a route of endocrine disruptor exposure. However, there is not a large concern of risk for humans.[73] Phytoestrogens are naturally occurring endocrine disrupters found in food. Soybeans contain a type of phytoestrogens called Geinstein.[72] It has also been found that eggs contain PAEs. In a study done in Turkey, researchers examined three types of eggs: battery, free-range, and organic. They found that battery eggs contained PAEs and free-range eggs had DDT concentrations in them. DDTs are pesticides and were banned in Turkey in the late 1900s.[74]

Indoor air and household dust

[edit]With the increase in household products containing pollutants and the decrease in the quality of building ventilation, indoor air has become a significant source of pollutant exposure.[75] Residents living in houses with wood floors treated in the 1960s with PCB-based wood finish have a much higher body burden than the general population.[76] A study of indoor house dust and dryer lint of 16 homes found high levels of all 22 different PBDE congeners tested for in all samples.[77] Recent studies suggest that contaminated house dust, not food, may be the major source of PBDE in the body.[78][79] One study estimated that ingestion of house dust accounts for up to 82% of humans' PBDE body burden.[80]

It has been shown that contaminated house dust is a primary source of lead in young children's bodies.[81] It may be that babies and toddlers ingest more contaminated house dust than the adults they live with, and therefore have much higher levels of pollutants in their systems.

Cosmetics and personal care products

[edit]Consumer goods are another potential source of exposure to endocrine disruptors. An analysis of the composition of 42 household cleaning and personal care products versus 43 "chemical-free" products has been performed. The products contained 55 different chemical compounds: 50 were found in the 42 conventional samples representing 170 product types, while 41 were detected in 43 "chemical-free" samples representing 39 product types. Parabens, a class of chemicals that has been associated with reproductive-tract issues, were detected in seven of the "chemical-free" products, including three sunscreens that did not list parabens on the label. Vinyl products such as shower curtains were found to contain more than 10% by weight of the compound DEHP, which when present in dust has been associated with asthma and wheezing in children. The risk of exposure to EDCs increases as products, both conventional and "chemical-free", are used in combination. "If a consumer used the alternative surface cleaner, tub and tile cleaner, laundry detergent, bar soap, shampoo and conditioner, facial cleanser and lotion, and toothpaste [he or she] would potentially be exposed to at least 19 compounds: 2 parabens, 3 phthalates, MEA, DEA, 5 alkylphenols, and 7 fragrances."[82]

An analysis of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals in Old Order Mennonite women in mid-pregnancy determined that they have much lower levels in their systems than the general population. Mennonites eat mostly fresh, unprocessed foods, farm without pesticides, and use few or no cosmetics or personal care products. One woman who had reported using hairspray and perfume had high levels of monoethyl phthalate, while the other women all had levels below detection. Three women who reported being in a car or truck within 48 hours of providing a urine sample had higher levels of diethylhexyl phthalate, which is found in polyvinyl chloride and is used in car interiors.[83]

Clothing

[edit]A more recent discussion around exposure to EDCs has been around clothing.

Greenpeace has reported on endocrine-disrupting chemicals in clothing since 2011. In 2013, Greenpeace found detectable levels of phthalates in 33 out of 35 printed articles of clothing from a global sample.[84] A particularly high level of DEHP was found in a t-shirt from Primark Germany, and a high level of DINP was found in a baby one-piece from American Apparel. PFCs were commonly found in swimwear and waterproof clothing. NPEs were found in most clothing articles as well.

A study by Greenpeace Germany published in 2014 again found high levels of phthalates in athletic gear.[85] The print of a t-shirt produced in Argentina contained phthalate levels as high as 15%, while a pair of gloves contained 6% phthalates. The study also found high levels of PFAS, nonoxynols and dimethylformamide in shoes and boots.

In research published in 2019, Li et al. stated that dermal absorption was the main route for phthalate exposure in infants,[86] including through clothing. It was found that laundering could not remove phthalates completely. Out of the six different types of phthalates that were measured, DEHP and DBP were found to be particularly present in infant clothing.

Tang et al. published research in 2019 that found all 15 different phthalates that were measured in preschoolers' clothing.[87] Levels were largely independent of country of manufacture though they differed by garment type, fabric composition, and garment color. It was found that "when children wore trousers, long-sleeved shirts, briefs and socks at the same time, the reproductive risks exceeded acceptable level".[87]

In a review of 120 articles from 2014 to 2023 about phthalates in clothing, it was found that while screen printing ink,[88] vinyl patches and synthetic leather may contain 30–60% phthalates, waterproof items such as infant mattress covers also contained very high levels of these chemicals.[71] It was also noted that manufacturers work to replace more regulated substances, such as DEHP, with newer ones, that may not yet be as tightly regulated.

Environment

[edit]

Additives added to plastics during manufacturing may leach into the environment after the plastic item is discarded; additives in microplastics in the ocean leach into ocean water and in plastics in landfills may escape and leach into the soil and then into groundwater.[89][90] The chemicals occur in plastics, pesticides, food containers, children's toys, industrial waste, and some personal care products which can enter and accumulate in the environment by contaminating the soil, air, and water.[91][92]

Types

[edit]All people are exposed to chemicals with estrogenic effects in their everyday life, because endocrine disrupting chemicals are found in low doses in thousands of products. Chemicals commonly detected in people include DDT, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), bisphenol A (BPA), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and a variety of phthalates.[93] In fact, almost all plastic products, including those advertised as BPA-free, have been found to leach endocrine-disrupting chemicals.[94] In a 2011, study it was found that some BPA-free products released more endocrine-active chemicals than the BPA-containing products.[95][96] Other forms of endocrine disruptors are phytoestrogens, compounds with estrogen activity found in plants.[97]

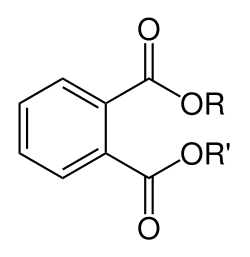

Xenoestrogens

[edit]Xenoestrogens are a type of xenohormone that imitates estrogen.[98] Synthetic xenoestrogens include widely used industrial compounds, such as PCBs, BPA and phthalates, which have estrogenic effects on a living organism.

Alkylphenols

[edit]Alkylphenols are xenoestrogens.[99] The European Union has implemented sales and use restrictions on certain applications in which nonylphenols are used because of their alleged "toxicity, persistence, and the liability to bioaccumulate" but the United States Environmental Protections Agency (EPA) has taken a slower approach to make sure that action is based on "sound science".[100]

The long-chain alkylphenols are used extensively as precursors to the detergents, as additives for fuels and lubricants, polymers, and as components in phenolic resins. These compounds are also used as building block chemicals that are also used in making fragrances, thermoplastic elastomers, antioxidants, oil field chemicals and fire retardant materials. Through the downstream use in making alkylphenolic resins, alkylphenols are also found in tires, adhesives, coatings, carbonless copy paper and high performance rubber products. They have been used in industry for over 40 years.

Certain alkylphenols are degradation products from nonionic detergents. Nonylphenol is considered to be a low-level endocrine disruptor owing to its tendency to mimic estrogen.[101][102]

Bisphenol A (BPA)

[edit]This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (March 2016) |

Bisphenol A is commonly found in plastic bottles, plastic food containers, dental materials, and the linings of metal food and infant formula cans. Another exposure comes from receipt paper commonly used at grocery stores and restaurants, because today the paper is commonly coated with a BPA containing clay for printing purposes.[103]

BPA is a known endocrine disruptor, and numerous studies have found that laboratory animals exposed to low levels of it have elevated rates of diabetes, mammary and prostate cancers, decreased sperm count, reproductive problems, early puberty, obesity, and neurological problems.[104][105][106][107] Studies in the US have shown that healthy women without any fertility problems found that urinary BPA was unrelated to time of pregnancy despite a shorter luteal phase (second part of the menstrual cycle) being reported.[108][109] Additional studies have been conducted in fertility centers say that BPA exposure is correlation with lower ovarian reserves.[110] To combat this, most women will undergo IVF to help with the poor ovarian stimulation response; seemingly all of them have elevated levels of BPA in the urinary tract.[111] Median conjugation of BPA concentrations were higher in those who did have a miscarriage compared to those who had a live birth.[112] All of these studies show that BPA can have an effect on ovarian functions and the pivotal early part of conception. One study did show racial or ethnic differences as Asian women were found to have an increased oocyte maturity rate, but all of the women had significantly lower concentration of BPA in the study.[113] Early developmental stages appear to be the period of greatest sensitivity to its effects, and some studies have linked prenatal exposure to later physical and neurological difficulties.[114] Regulatory bodies have determined safety levels for humans, but those safety levels are currently being questioned or are under review as a result of new scientific studies.[115][116] A 2011 cross-sectional study that investigated the number of chemicals pregnant women are exposed to in the U.S. found BPA in 96% of women.[117] In 2010 the World Health Organization expert panel recommended no new regulations limiting or banning the use of bisphenol A, stating that "initiation of public health measures would be premature."[118]

In August 2008, the U.S. FDA issued a draft reassessment, reconfirming their initial opinion that, based on scientific evidence, BPA is safe.[119] However, in October 2008, FDA's advisory Science Board concluded that the Agency's assessment was "flawed" and had not proven the chemical to be safe for formula-fed infants.[120] In January 2010, the FDA issued a report indicating that, due to findings of recent studies that used novel approaches in testing for subtle effects, both the National Toxicology Program at the National Institutes of Health as well as the FDA have some level of concern regarding the possible effects of BPA on the brain and behavior of fetuses, infants and younger children.[121] In 2012 the FDA did ban the use of BPA in baby bottles; however, the Environmental Working Group called the ban "purely cosmetic". In a statement they said, "If the agency truly wants to prevent people from being exposed to this toxic chemical associated with a variety of serious and chronic conditions it should ban its use in cans of infant formula, food and beverages." The Natural Resources Defense Council called the move inadequate saying, the FDA needs to ban BPA from all food packaging.[122] In a statement a FDA spokesman said the agency's action was not based on safety concerns and that "the agency continues to support the safety of BPA for use in products that hold food."[123]

A program initiated by NIEHS, NTP, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (named CLARITY-BPA) found no effect of chronic exposure to BPA on rats[124] and the FDA considers currently authorized uses of BPA to be safe for consumers.[125]

The Environmental Protection Agency set[when?] a reference dose for BPA at 50 μg/kg/day for mammals, although exposure to doses lower than the reference dose has been shown to affect both male and female reproductive systems.[126]

Bisphenol S (BPS) and bisphenol F (BPF)

[edit]Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F are analogs of bisphenol A. They are commonly found in thermal receipts, plastics, and household dust.

Traces of BPS have also been found in personal care products.[127] It is more presently being used because of the ban of BPA. BPS is used in place of BPA in BPA-free items. However, BPS and BPF have been shown to be endocrine disruptors as much as BPA.[128][129]

DDT

[edit]

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was first used as a pesticide against Colorado potato beetles on crops beginning in 1936.[130] An increase in the incidence of malaria, epidemic typhus, dysentery, and typhoid fever led to its use against the mosquitoes, lice, and houseflies that carried these diseases. Before World War II, pyrethrum, an extract of a flower from Japan, had been used to control these insects and the diseases they can spread. During World War II, Japan stopped exporting pyrethrum, forcing the search for an alternative. Fearing an epidemic outbreak of typhus, every British and American soldier was issued DDT, who used it to routinely dust beds, tents, and barracks all over the world.

DDT was approved for general, non-military use after the war ended.[130] It became used worldwide to increase monoculture crop yields that were threatened by pest infestation, and to reduce the spread of malaria which had a high mortality rate in many parts of the world. Its use for agricultural purposes has since been prohibited by national legislation of most countries, while its use as a control against malaria vectors is permitted, as specifically stated by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.[131]

As early as 1946, the harmful effects of DDT on birds, beneficial insects, fish, and marine invertebrates were seen in the environment. The most infamous example of these effects were seen in the eggshells of large predatory birds, which did not develop to be thick enough to support the adult bird sitting on them.[132] Further studies found DDT in high concentrations in carnivores all over the world, the result of biomagnification through the food chain.[133] Twenty years after its widespread use, DDT was found trapped in ice samples taken from Antarctic snow, suggesting wind and water are another means of environmental transport.[134] Recent studies show the historical record of DDT deposition on remote glaciers in the Himalayas.[135]

More than sixty years ago when biologists began to study the effects of DDT on laboratory animals, it was discovered that DDT interfered with reproductive development.[136][137] Recent studies suggest DDT may inhibit the proper development of female reproductive organs that adversely affects reproduction into maturity.[138] Additional studies suggest that a marked decrease in fertility in adult males may be due to DDT exposure.[139] Most recently, it has been suggested that exposure to DDT in utero can increase a child's risk of childhood obesity.[140] DDT is still used as anti-malarial insecticide in Africa and parts of Southeast Asia in limited quantities.

Polychlorinated biphenyls

[edit]Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a class of chlorinated compounds used as industrial coolants and lubricants. PCBs are created by heating benzene, a byproduct of gasoline refining, with chlorine.[141] They were first manufactured commercially by the Swann Chemical Company in 1927.[142] In 1933, the health effects of direct PCB exposure was seen in those who worked with the chemicals at the manufacturing facility in Alabama. In 1935, Monsanto acquired the company, taking over US production and licensing PCB manufacturing technology internationally.

General Electric was one of the largest US companies to incorporate PCBs into manufactured equipment.[142] Between 1952 and 1977, the New York GE plant had dumped more than 500,000 pounds of PCB waste into the Hudson River. PCBs were first discovered in the environment far from its industrial use by scientists in Sweden studying DDT.[143]

The effects of acute exposure to PCBs were well known within the companies who used Monsanto's PCB formulation who saw the effects on their workers who came into contact with it regularly. Direct skin contact results in a severe acne-like condition called chloracne.[144] Exposure increases the risk of skin cancer,[145] liver cancer,[146] and brain cancer.[145][147] Monsanto tried for years to downplay the health problems related to PCB exposure in order to continue sales.[148]

The detrimental health effects of PCB exposure to humans became undeniable when two separate incidents of contaminated cooking oil poisoned thousands of residents in Japan (Yushō disease, 1968) and Taiwan (Yu-cheng disease, 1979),[149] leading to a worldwide ban on PCB use in 1977. Recent studies show the endocrine interference of certain PCB congeners is toxic to the liver and thyroid,[150] increases childhood obesity in children exposed prenatally,[140] and may increase the risk of developing diabetes.[151][152]

PCBs in the environment may also be related to reproductive and infertility problems in wildlife. In Alaska, it is thought that they may contribute to reproductive defects, infertility and antler malformation in some deer populations. Declines in the populations of otters and sea lions may also be partially due to their exposure to PCBs, the insecticide DDT, other persistent organic pollutants. Bans and restrictions on the use of EDCs have been associated with a reduction in health problems and the recovery of some wildlife populations.[153]

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers

[edit]Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are a class of compounds found in flame retardants used in plastic cases of televisions and computers, electronics, carpets, lighting, bedding, clothing, car components, foam cushions and other textiles. Potential health concern: PBDEs are structurally very similar to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and have similar neurotoxic effects.[154] Research has correlated halogenated hydrocarbons, such as PCBs, with neurotoxicity.[150] PBDEs are similar in chemical structure to PCBs, and it has been suggested that PBDEs act by the same mechanism as PCBs.[150]

In the 1930s and 1940s, the plastics industry developed technologies to create a variety of plastics with broad applications.[155] Once World War II began, the US military used these new plastic materials to improve weapons, protect equipment, and to replace heavy components in aircraft and vehicles.[155] After WWII, manufacturers saw the potential plastics could have in many industries, and plastics were incorporated into new consumer product designs. Plastics began to replace wood and metal in existing products as well, and today plastics are the most widely used manufacturing materials.[155]

By the 1960s, all homes were wired with electricity and had numerous electrical appliances. Cotton had been the dominant textile used to produce home furnishings,[156] but now home furnishings were composed of mostly synthetic materials. More than 500 billion cigarettes were consumed each year in the 1960s, as compared to less than 3 billion per year in the beginning of the twentieth century.[157] When combined with high-density living, the potential for home fires was higher in the 1960s than it had ever been in the US. By the late 1970s, approximately 6000 people in the US died each year in home fires.[158]

In 1972, in response to this situation, the National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control was created to study the fire problem in the US. In 1973 they published their findings in "America Burning", a 192-page report that made recommendations to increase fire prevention.[159] Most of the recommendations dealt with fire prevention education and improved building engineering, such as the installation of fire sprinklers and smoke detectors. The Commission expected that with the recommendations, a 5% reduction in fire losses could be expected each year, halving the annual losses within 14 years.

Historically, treatments with alum and borax were used to reduce the flammability of fabric and wood, as far back as Roman times.[160] Since it is a non-absorbent material once created, flame retardant chemicals are added to plastic during the polymerization reaction when it is formed. Organic compounds based on halogens like bromine and chlorine are used as the flame retardant additive in plastics, and in fabric based textiles as well.[160] The widespread use of brominated flame retardants may be due to the push from Great Lakes Chemical Corporation (GLCC) to profit from its huge investment in bromine.[161] In 1992, the world market consumed approximately 150,000 tonnes of bromine-based flame retardants, and GLCC produced 30% of the world supply.[160]

PBDEs have the potential to disrupt thyroid hormone balance and contribute to a variety of neurological and developmental deficits, including low intelligence and learning disabilities.[162][163] Many of the most common PBDE's were banned in the European Union in 2006.[164] Studies with rodents have suggested that even brief exposure to PBDEs can cause developmental and behavior problems in juvenile rodents[47][165] and exposure interferes with proper thyroid hormone regulation.[166]

Phthalates

[edit]Phthalates are found in some soft toys, flooring, medical equipment, cosmetics and air fresheners. They are of potential health concern because they are known to disrupt the endocrine system of animals, and some research has implicated them in the rise of birth defects of the male reproductive system.[53][167][168]

Although an expert panel has concluded that there is "insufficient evidence" that they can harm the reproductive system of infants,[169] California,[170][171] Washington state,[172] and Europe have banned them from toys. One phthalate, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), used in medical tubing, catheters and blood bags, may harm sexual development in male infants.[167] In 2002, the Food and Drug Administration released a public report which cautioned against exposing male babies to DEHP. Although there are no direct human studies the FDA report states: "Exposure to DEHP has produced a range of adverse effects in laboratory animals, but of greatest concern are effects on the development of the male reproductive system and production of normal sperm in young animals. In view of the available animal data, precautions should be taken to limit the exposure of the developing male to DEHP".[173] Similarly, phthalates may play a causal role in disrupting masculine neurological development when exposed prenatally.[174]

Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) has also disrupted insulin and glucagon signaling in animal models.[175]

Perfluorooctanoic acid

[edit]PFOA is a stable chemical that has been used for its grease-, fire-, and water-resistant properties in products such as non-stick pan coatings, furniture, firefighter equipment, industrial, and other common household items.[176][177] There is evidence to suggest that PFOA is an endocrine disruptor affecting male and female reproductive systems.[177] PFOA delivered to pregnant rats produced male offspring with decreased levels of 3-β and 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase,[177] a gene that transcribes for proteins involved in the production of sperm.[178] Adult women have exhibited low progesterone and androstenedione production when exposed to PFOA, leading to menstrual and reproductive health issues.[177] PFOA exerts hormonal effects including alteration of thyroid hormone levels. Blood serum levels of PFOA were associated with an increased time to pregnancy—or "infertility"—in a 2009 study. PFOA exposure is associated with decreased semen quality. PFOA appeared to act as an endocrine disruptor by a potential mechanism on breast maturation in young girls. A C8 Science Panel status report noted an association between exposure in girls and a later onset of puberty.

Other suspected endocrine disruptors

[edit]Some other examples of putative EDCs are polychlorinated dibenzo-dioxins (PCDDs) and -furans (PCDFs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenol derivatives and a number of pesticides (most prominent being organochlorine insecticides like endosulfan, kepone (chlordecone) and DDT and its derivatives, the herbicide atrazine, and the fungicide vinclozolin), the contraceptive 17-alpha ethinylestradiol, as well as naturally occurring phytoestrogens such as genistein and mycoestrogens such as zearalenone.

The molting in crustaceans is an endocrine-controlled process. In the marine penaeid shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei, exposure to endosulfan resulted increased susceptibility to acute toxicity and increased mortalities in the postmolt stage of the shrimp.[179]

Many sunscreens contain oxybenzone, a chemical blocker that provides broad-spectrum UV coverage, yet is subject to a lot of controversy due its potential estrogenic effect in humans.[180]

Tributyltin (TBT) are organotin compounds. For 40 years TBT was used as a biocide in anti-fouling paint, commonly known as bottom paint. TBT has been shown to impact invertebrate and vertebrate development, disrupting the endocrine system, resulting in masculinization, lower survival rates, as well as many health problems in mammals.

Temporal trends of body burden

[edit]Since being banned, the average human body burdens of DDT and PCB have been declining.[68][181][182] Since their ban in 1972, the PCB body burden in 2009 is one-hundredth of what it was in the early 1980s. On the other hand, monitoring programs of European breast milk samples have shown that PBDE levels are increasing.[68][182] An analysis of PBDE content in breast milk samples from Europe, Canada, and the US shows that levels are 40 times higher for North American women than for Swedish women, and that levels in North America are doubling every two to six years.[183][184]

It has been discussed that the long-term slow decline in average body temperature observed since the beginning of the industrial revolution[185] may result from disrupted thyroid hormone signalling.[186]

Animal models

[edit]As endocrine disruptors affect complex metabolic, reproductive, and neuroendocrine systems, animal models may be used to assess the risk of endocrine disrupting chemicals.[187] Some common animal models used for assessing these risks are mice, fish egg yolks, and frogs.[188]

Mice

[edit]

Genetically-engineered mice can be used as population-based genetic foundations. For instance, one population is named multi-parent and can be a collaborative cross (CC) or diversity outbred (DO) strain.[189][190][191]

The eight founder strains combine strains that are wild-derived (with high genetic diversity) and research bred strains. Each genetically differential line is used to assess EDCs responses.[192]

The CC population consists of 83 inbred mouse strains that over many generations in labs came from the eight founder strains. While DO mice have the identical alleles to the CC mice population, there are two major differences: every individual is unique, allowing for hundreds of individuals to be applied in one mapping study, making DO mice useful for determining genetic relationships; however, DO individuals cannot be reproduced.[citation needed]

Transgenic

[edit]These rodents, mainly mice, have been bred by inserting other genes from another organism to make transgenic lines (thousands of lines) of rodents, in a technique such as CRISPR.[193]

Genes may be manipulated in a particular cell populations if done under the correct conditions.[194] For endocrine-disrupting chemical research, these rodents are used to produce humanized mouse models.[195] Additionally, scientists use gene knockout lines of mice in order to study how certain mechanisms work when impacted by EDCs.[195][196] Transgenic rodents are used to study mechanisms impacted by EDC, but take a long time to produce and are expensive.[citation needed]

Social models

[edit]Experiments (gene by environment) with rodent models may be able to discover if there are mechanisms that EDCs could impact in behavioral disorders.[197] This is because prairie and pine voles are socially monogamous, making them a better model for human social behaviors and development in relation to EDCs.[198][199][200]

Zebrafish

[edit]

The endocrine systems between mammals and fish are similar; because of this, zebrafish (Danio rerio) may be used.[201][better source needed]

The zebrafish embryos are transparent, relatively small fish (larvae are less than a few millimeters in size),[202] and have simple modes of endocrine disruption,[203] along with homologous physiological, sensory, anatomical and signal-transduction mechanisms similar to mammals. Another helpful tool available to scientists is their recorded genome along with multiple transgenic lines accessible for breeding. Zebrafish and mammalian genomes when compared have prominent similarities with about 80% of human genes expressed in the fish.[204][205][202]

Directions of research

[edit]Research on endocrine disruptors is challenged by five complexities requiring special trial designs and sophisticated study protocols:[206]

- The dissociation of space means that, although disruptors may act by a common pathway via hormone receptors, their impact may also be mediated by effects at the levels of transport proteins, deiodinases, degradation of hormones or modified setpoints of feedback loops (i.e. allostatic load).[207]

- The dissociation of time may ensue from the fact that unwanted effects may be triggered in a small time window in the embryonal or fetal period, but consequences may ensue decades later or even in the generation of grandchildren.[208]

- The dissociation of substance results from additive, multiplicative or more complex interactions of disruptors in combination that yield fundamentally different effects from that of the respective substances alone.[206]

- The dissociation of dose implies that dose-effect relationships can be nonlinear and sometimes even U-shaped, so that low or medium doses may have stronger effects than high doses.[207]

- The dissociation of sex reflects the fact that effects may be different depending on whether embryos or fetuses are female or male.[208][209]

Legal approach

[edit]United States

[edit]The multitude of possible endocrine disruptors are technically regulated in the United States by many laws, including the Toxic Substances Control Act, the Food Quality Protection Act,[210] the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the Clean Air Act.

The Congress of the United States has improved the evaluation and regulation process of drugs and other chemicals. The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 and the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1996 simultaneously provided the first legislative direction requiring the EPA to address endocrine disruption through establishment of a program for screening and testing of chemical substances.

In 1998, the EPA announced the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program by establishment of a framework for priority setting, screening and testing more than 85,000 chemicals in commerce. While the Food Quality Protection Act only required the EPA to screen pesticides for potential to produce effects similar to estrogens in humans, it also gave the EPA the authority to screen other types of chemicals and endocrine effects.[210] Based on recommendations from an advisory panel, the agency expanded the screening program to include male hormones, the thyroid system, and effects on fish and other wildlife.[210] The basic concept behind the program is that prioritization will be based on existing information about chemical uses, production volume, structure-activity and toxicity. Screening is done by use of in vitro test systems (by examining, for instance, if an agent interacts with the estrogen receptor or the androgen receptor) and via the use of in animal models, such as development of tadpoles and uterine growth in prepubertal rodents. Full-scale testing will examine effects not only in mammals (rats) but also in a number of other species (frogs, fish, birds and invertebrates). Since the theory involves the effects of these substances on a functioning system, animal testing is essential for scientific validity, but has been opposed by animal rights groups. Similarly, proof that these effects occur in humans would require human testing, and such testing also has opposition.

After failing to meet several deadlines to begin testing, the EPA finally announced that they were ready to begin the process of testing dozens of chemical entities that are suspected endocrine disruptors early in 2007, eleven years after the program was announced. When the final structure of the tests was announced there was objection to their design. Critics have charged that the entire process has been compromised by chemical company interference.[211] In 2005, the EPA appointed a panel of experts to conduct an open peer-review of the program and its orientation. Their results found that "the long-term goals and science questions in the EDC program are appropriate",[212] however this study was conducted over a year before the EPA announced the final structure of the screening program. The EPA is still finding it difficult to execute a credible and efficient endocrine testing program.[210]

As of 2016, the EPA had estrogen screening results for 1,800 chemicals.[210]

Europe

[edit]In 2013, a number of pesticides containing endocrine disrupting chemicals were in draft EU criteria to be banned. On 2 May, US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiators insisted the EU drop the criteria. They stated that a risk-based approach should be taken on regulation. Later the same day Catherine Day wrote to Karl Falkenberg asking for the criteria to be removed.[213]

The European Commission had been to set criteria by December 2013 identifying endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in thousands of products—including disinfectants, pesticides and toiletries—that have been linked to cancers, birth defects and development disorders in children. However, the body delayed the process, prompting Sweden to state that it would sue the commission in May 2014—blaming chemical industry lobbying for the disruption.[214]

"This delay is due to the European chemical lobby, which put pressure again on different commissioners. Hormone disrupters are becoming a huge problem. In some places in Sweden we see double-sexed fish. We have scientific reports on how this affects fertility of young boys and girls, and other serious effects," Swedish Environment Minister Lena Ek told the AFP, noting that Denmark had also demanded action.[214]

In November 2014, the Copenhagen-based Nordic Council of Ministers released its own independent report that estimated the impact of environmental EDCs on male reproductive health, and the resulting cost to public health systems. It concluded that EDCs likely cost health systems across the EU anywhere from 59 million to 1.18 billion Euros a year, noting that even this represented only "a fraction of the endocrine related diseases".[215]

In 2020, the EU published their Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability which is concerned with a green transition of the chemical industry away from xenohormones and other hazardous chemicals.

Environmental and human body cleanup

[edit]There is evidence that once a pollutant is no longer in use, or once its use is heavily restricted, the human body burden of that pollutant declines. Through the efforts of several large-scale monitoring programs,[93][216] the most prevalent pollutants in the human population are fairly well known. The first step in reducing the body burden of these pollutants is eliminating or phasing out their production.

The second step toward lowering human body burden is awareness of and potentially labeling foods that are likely to contain high amounts of pollutants. This strategy has worked in the past—pregnant and nursing women are cautioned against eating seafood that is known to accumulate high levels of mercury.[217]

The most challenging aspect of this problem is discovering how to eliminate these compounds from the environment and where to focus remediation efforts. Even pollutants no longer in production persist in the environment and bio-accumulate in the food chain. An understanding of how these chemicals, once in the environment, move through ecosystems, is essential to designing ways to isolate and remove them. Global efforts have been made to label the most common POPs routinely found in the environment through usage of chemicals like insecticides. The twelve main POPs have been evaluated and placed in a demographic so as to streamline the information around the general population. Such facilitation has allowed nations around the world to effectively work on the testing and reduction of the usage of these chemicals. With an effort to reduce the presence of such chemicals in the environment, they can reduce the leaching of POPs into food sources which contaminate the animals commercially fed to the U.S. population.[218]

Many persistent organic compounds, PCB, DDT and PBDE included, accumulate in river and marine sediments. Several processes are currently being used by the EPA to clean up heavily polluted areas, as outlined in their Green Remediation program.[219]

Naturally occurring microbes that degrade PCB congeners to remediate contaminated areas are utilized.[220]

There are many success stories of cleanup efforts of large heavily contaminated Superfund sites. A 10-acre (40,000 m2) landfill in Austin, Texas, contaminated with illegally dumped VOCs was restored in a year to a wetland and educational park.[221]

A US uranium enrichment site that was contaminated with uranium and PCBs was cleaned up with high tech equipment used to find the pollutants within the soil.[222] The soil and water at a polluted wetlands site were cleaned of VOCs, PCBs and lead, native plants were installed as biological filters, and a community program was implemented to ensure ongoing monitoring of pollutant concentrations in the area.[223] These case studies are encouraging due to the short amount of time needed to remediate the site and the high level of success achieved.

Studies suggest that bisphenol A,[224] certain PCBs,[225] and phthalate compounds[226] are preferentially eliminated from the human body through sweat. Although some pollutants like bisphenol A (BPA) are preferentially eliminated from the human body through sweat, recent scientific advances have been made to increase the rate of elimination of pollutants from the human body. For example, BPA removal techniques have been proposed that use enzymes such as laccase and peroxidase to degrade BPA into less harmful compounds. Another technique for BPA removal is the use of highly reactive radicals for degradation.[227]

Economic effects

[edit]Human exposure may cause some health effects, such as lower IQ, adult obesity, female reproductive disorders, and male reproductive disorders.[228] These effects may lead to lost productivity, disability, or premature death in some people. One source estimated that, within the European Union, this economic effect might have about twice the economic impact as the effects caused by mercury and lead contamination.[229]

Within the last 5 years, the socio-economic burden of EDC-associated health effects was recorded at an estimated annual cost of €163 in the EU and $340 billion in the USA, which can even be viewed as an underestimate due to how many health outcomes take place due to EDC exposure[228]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Krimsky S (December 2001). "An epistemological inquiry into the endocrine disruptor thesis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 948 (1): 130–142. Bibcode:2001NYASA.948..130K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03994.x. PMID 11795392. S2CID 41532171.

- ^ Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. (June 2009). "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement" (PDF). Endocrine Reviews. 30 (4): 293–342. doi:10.1210/er.2009-0002. PMC 2726844. PMID 19502515. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Endocrine Disrupting Compounds". National Institutes of Health · U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009.

- ^ Casals-Casas C, Desvergne B (17 March 2011). "Endocrine disruptors: from endocrine to metabolic disruption". Annual Review of Physiology. 73 (1): 135–162. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142200. PMID 21054169.

- ^ "Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs)". www.endocrine.org. 24 January 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Staff (5 June 2013). "Endocrine Disruptors". NIEHS.

- ^ Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR, Lee DH, et al. (June 2012). "Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses". Endocrine Reviews. 33 (3): 378–455. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1050. PMC 3365860. PMID 22419778.

- ^ Crisp TM, Clegg ED, Cooper RL, Wood WP, Anderson DG, Baetcke KP, et al. (February 1998). "Environmental endocrine disruption: an effects assessment and analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106. 106 (Suppl 1): 11–56. doi:10.2307/3433911. JSTOR 3433911. PMC 1533291. PMID 9539004.

- ^ Huang AC, Nelson C, Elliott JE, Guertin DA, Ritland C, Drouillard K, et al. (July 2018). "River otters (Lontra canadensis) "trapped" in a coastal environment contaminated with persistent organic pollutants: Demographic and physiological consequences". Environmental Pollution. 238: 306–316. Bibcode:2018EPoll.238..306H. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.03.035. PMID 29573713.

- ^ Eskenazi B, Chevrier J, Rauch SA, Kogut K, Harley KG, Johnson C, et al. (February 2013). "In utero and childhood polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) exposures and neurodevelopment in the CHAMACOS study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (2): 257–62. Bibcode:2013EnvHP.121..257E. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205597. PMC 3569691. PMID 23154064.

- ^ Jurewicz J, Hanke W (June 2011). "Exposure to phthalates: reproductive outcome and children health. A review of epidemiological studies". International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 24 (2): 115–41. doi:10.2478/s13382-011-0022-2. PMID 21594692.

- ^ Bornehag CG, Engdahl E, Unenge Hallerbäck M, Wikström S, Lindh C, Rüegg J, et al. (May 2021). "Prenatal exposure to bisphenols and cognitive function in children at 7 years of age in the Swedish SELMA study". Environment International. 150 106433. Bibcode:2021EnInt.15006433B. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2021.106433. PMID 33637302. S2CID 232064637.

- ^ Repouskou A, Papadopoulou AK, Panagiotidou E, Trichas P, Lindh C, Bergman Å, et al. (June 2020). "Long term transcriptional and behavioral effects in mice developmentally exposed to a mixture of endocrine disruptors associated with delayed human neurodevelopment". Scientific Reports. 10 (1) 9367. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.9367R. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66379-x. PMC 7283331. PMID 32518293.

- ^ Lupu D, Andersson P, Bornehag CG, Demeneix B, Fritsche E, Gennings C, et al. (June 2020). "The ENDpoiNTs Project: Novel Testing Strategies for Endocrine Disruptors Linked to Developmental Neurotoxicity". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (11): 3978. doi:10.3390/ijms21113978. PMC 7312023. PMID 32492937.

- ^ "State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals". World Health Organization. 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM (October 1993). "Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans". Environ. Health Perspect. 101 (5): 378–84. doi:10.2307/3431890. JSTOR 3431890. PMC 1519860. PMID 8080506.

- ^ Grady D (6 September 2010). "In Feast of Data on BPA Plastic, No Final Answer". The New York Times.

A fierce debate has resulted, with some dismissing the whole idea of endocrine disruptors.

- ^ Bern HA, Blair P, Brasseur S, Colborn T, Cunha GR, Davis W, et al. (1992). "Statement from the Work Session on Chemically-Induced Alterations in Sexual Development: The Wildlife/Human Connection" (PDF). In Clement C, Colborn T (eds.). Chemically-induced alterations in sexual and functional development-- the wildlife/human connection. Princeton, N.J: Princeton Scientific Pub. Co. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-911131-35-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ Bantle J, Bowerman WW IV, Carey C, Colborn T, Deguise S, Dodson S, et al. (May 1995). "Statement from the Work Session on Environmentally induced Alterations in Development: A Focus on Wildlife". Environmental Health Perspectives. 103 (Suppl 4): 3–5. doi:10.2307/3432404. JSTOR 3432404. PMC 1519268. PMID 17539108.

- ^ Benson WH, Bern HA, Bue B, Colborn T, Cook P, Davis WP, et al. (1997). "Statement from the work session on chemically induced alterations in functional development and reproduction of fishes". In Rolland RM, Gilbertson M, Peterson RE (eds.). Chemically Induced Alterations in Functional Development and Reproduction of Fishes. Society of Environmental Toxicology & Chemist. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-1-880611-19-7.

- ^ Alleva E, Brock J, Brouwer A, Colborn T, Fossi MC, Gray E, et al. (1998). "Statement from the work session on environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals: neural, endocrine, and behavioral effects". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 14 (1–2): 1–8. Bibcode:1998ToxIH..14....1.. doi:10.1177/074823379801400103. PMID 9460166. S2CID 45902764.

- ^ Brock J, Colborn T, Cooper R, Craine DA, Dodson SF, Garry VF, et al. (1999). "Statement from the Work Session on Health Effects of Contemporary-Use Pesticides: the Wildlife / Human Connection". Toxicol Ind Health. 15 (1–2): 1–5. Bibcode:1999ToxIH..15....1.. doi:10.1191/074823399678846547.

- ^ Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. (June 2009). "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement". Endocrine Reviews. 30 (4): 293–342. doi:10.1210/er.2009-0002. PMC 2726844. PMID 19502515.

- ^ "Position statement: Endocrine-disrupting chemicals" (PDF). Endocrine News. 34 (8): 24–27. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2010.

- ^ Sangeetha S, Vimalkumar K, Loganathan BG (June 2021). "Environmental Contamination and Human Exposure to Select Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: A Review". Sustainable Chemistry. 2 (2): 343–380. doi:10.3390/suschem2020020. ISSN 2673-4079.

- ^ Visser MJ. "Cold, Clear, and Deadly". Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Damstra T, Barlow S, Bergman A, Kavlock R, Van der Kraak G (2002). "REPIDISCA-Global assessment of the state-of-the-science of endocrine disruptors". International programme on chemical safety, World Health Organization. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Harrison PT, Humfrey CD, Litchfield M, Peakall D, Shuker LK (1995). "Environmental oestrogens: consequences to human health and wildlife" (PDF). IEH assessment. Medical Research Council, Institute for Environment and Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ "EDC Human Effects". e.hormone. Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane and Xavier Universities. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Golden RJ, Noller KL, Titus-Ernstoff L, Kaufman RH, Mittendorf R, Stillman R, et al. (March 1998). "Environmental endocrine modulators and human health: an assessment of the biological evidence". Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 28 (2): 109–227. doi:10.1080/10408449891344191. PMID 9557209.

- ^ Willis IC (2007). Progress in Environmental Research. New York: Nova Publishers. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-60021-618-3.

- ^ "State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals – 2012". World Health Organization. 2013. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Anatomy of the Endocrine System". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Services Do. "Hormonal (endocrine) system". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ "Hormonal (endocrine) system". Better Health Channel. The Department of Health, Victorian Government. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Kim YJ, Tamadon A, Park HT, Kim H, Ku SY (September 2016). "The role of sex steroid hormones in the pathophysiology and treatment of sarcopenia". Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia. 2 (3): 140–155. doi:10.1016/j.afos.2016.06.002. PMC 6372754. PMID 30775480.

- ^ Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR, Lee DH, et al. (1 June 2012). "Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses". Endocrine Reviews. 33 (3): 378–455. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1050. ISSN 0163-769X. PMC 3365860. PMID 22419778.

- ^ "Bisphenol A Overview". Environment California. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011.

- ^ Guo YL, Lambert GH, Hsu CC (September 1995). "Growth abnormalities in the population exposed in utero and early postnatally to polychlorinated biphenyls and dibenzofurans". Environ. Health Perspect. 103 (Suppl 6): 117–22. doi:10.2307/3432359. JSTOR 3432359. PMC 1518940. PMID 8549457.

- ^ a b Bigsby R, Chapin RE, Daston GP, Davis BJ, Gorski J, Gray LE, et al. (August 1999). "Evaluating the effects of endocrine disruptors on endocrine function during development". Environ. Health Perspect. 107 (Suppl 4): 613–8. doi:10.2307/3434553. JSTOR 3434553. PMC 1567510. PMID 10421771.

- ^ Castro DJ, Löhr CV, Fischer KA, Pereira CB, Williams DE (December 2008). "Lymphoma and lung cancer in offspring born to pregnant mice dosed with dibenzo[a, l]pyrene: the importance of in utero vs. lactational exposure". Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 233 (3): 454–8. Bibcode:2008ToxAP.233..454C. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.09.009. PMC 2729560. PMID 18848954.

- ^ Eriksson P, Lundkvist U, Fredriksson A (1991). "Neonatal exposure to 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl: changes in spontaneous behaviour and cholinergic muscarinic receptors in the adult mouse". Toxicology. 69 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/0300-483X(91)90150-Y. PMID 1926153.

- ^ Recabarren SE, Rojas-García PP, Recabarren MP, Alfaro VH, Smith R, Padmanabhan V, et al. (December 2008). "Prenatal testosterone excess reduces sperm count and motility". Endocrinology. 149 (12): 6444–8. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0785. hdl:10533/142155. PMID 18669598.

- ^ Szabo DT, Richardson VM, Ross DG, Diliberto JJ, Kodavanti PR, Birnbaum LS (January 2009). "Effects of perinatal PBDE exposure on hepatic phase I, phase II, phase III, and deiodinase 1 gene expression involved in thyroid hormone metabolism in male rat pups". Toxicol. Sci. 107 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn230. PMC 2638650. PMID 18978342.

- ^ Lilienthal H, Hack A, Roth-Härer A, Grande SW, Talsness CE (February 2006). "Effects of developmental exposure to 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (PBDE-99) on sex steroids, sexual development, and sexually dimorphic behavior in rats". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (2): 194–201. Bibcode:2006EnvHP.114..194L. doi:10.1289/ehp.8391. PMC 1367831. PMID 16451854.

- ^ Talsness CE, Shakibaei M, Kuriyama SN, Grande SW, Sterner-Kock A, Schnitker P, et al. (July 2005). "Ultrastructural changes observed in rat ovaries following in utero and lactational exposure to low doses of a polybrominated flame retardant". Toxicol. Lett. 157 (3): 189–202. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.02.001. PMID 15917144.

- ^ a b Eriksson P, Viberg H, Jakobsson E, Orn U, Fredriksson A (May 2002). "A brominated flame retardant, 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether: uptake, retention, and induction of neurobehavioral alterations in mice during a critical phase of neonatal brain development". Toxicol. Sci. 67 (1): 98–103. doi:10.1093/toxsci/67.1.98. PMID 11961221.

- ^ Viberg H, Johansson N, Fredriksson A, Eriksson J, Marsh G, Eriksson P (July 2006). "Neonatal exposure to higher brominated diphenyl ethers, hepta-, octa-, or nonabromodiphenyl ether, impairs spontaneous behavior and learning and memory functions of adult mice". Toxicol. Sci. 92 (1): 211–8. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj196. PMID 16611620.

- ^ Rogan WJ, Ragan NB (July 2003). "Evidence of effects of environmental chemicals on the endocrine system in children". Pediatrics. 112 (1 Pt 2): 247–52. doi:10.1542/peds.112.S1.247. PMID 12837917. S2CID 13058233.

- ^ Bern HA (November 1992). "The development of the role of hormones in development—a double remembrance". Endocrinology. 131 (5): 2037–8. doi:10.1210/endo.131.5.1425407. PMID 1425407.

- ^ Colborn T, Carroll LE (2007). "Pesticides, sexual development, reproduction, and fertility: current perspective and future". Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. 13 (5): 1078–1110. doi:10.1080/10807030701506405. S2CID 34600913.

- ^ a b Collaborative on Health, the Environment's Learning, Developmental Disabilities Initiative (1 July 2008). "Scientific Consensus Statement on Environmental Agents Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders" (PDF). Institute for Children's Environmental Health. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ a b Swan SH, Main KM, Liu F, Stewart SL, Kruse RL, Calafat AM, et al. (August 2005). "Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (8): 1056–61. Bibcode:2005EnvHP.113.1056S. doi:10.1289/ehp.8100. PMC 1280349. PMID 16079079.

- ^ McEwen GN, Renner G (January 2006). "Validity of anogenital distance as a marker of in utero phthalate exposure". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (1): A19–20, author reply A20–1. doi:10.1289/ehp.114-1332693. PMC 1332693. PMID 16393642.

- ^ Postellon DC (June 2008). "Baby care products". Pediatrics. 121 (6): 1292, author reply 1292–3. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0401. PMID 18519505. S2CID 27956545.

- ^ Romano-Riquer SP, Hernández-Avila M, Gladen BC, Cupul-Uicab LA, Longnecker MP (May 2007). "Reliability and determinants of anogenital distance and penis dimensions in male newborns from Chiapas, Mexico". Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 21 (3): 219–28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00810.x. PMC 3653615. PMID 17439530.

- ^ Maldonado-Cárceles AB, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Vera-Porras EM, Árense-Gonzalo JJ, Oñate-Celdrán J, Samper-Mateo P, et al. (March 2017). "Anogenital Distance, a Biomarker of Prenatal Androgen Exposure Is Associated With Prostate Cancer Severity". The Prostate. 77 (4): 406–411. doi:10.1002/pros.23279. PMID 27862129.

- ^ Marín-Martínez FM, Arense-Gonzalo JJ, Artes MA, Bobadilla Romero ER, García Porcel VJ, Alcon Cerro P, et al. (November 2023). "Anogenital distance, a biomarker of fetal androgen exposure and the risk of prostate cancer: A case-control study". Urologia. 90 (4): 715–719. doi:10.1177/03915603231192736. PMID 37606191.

- ^ Harold Z (2011). Human Toxicology of Chemical Mixtures (2nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-3463-8.

- ^ Yu MH, Tsunoda H, Tsunoda M (2016). Environmental Toxicology: Biological and Health Effects of Pollutants (Third ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-4038-2.

- ^ Toporova L, Balaguer P (February 2020). "Nuclear receptors are the major targets of endocrine disrupting chemicals" (PDF). Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 502 110665. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2019.110665. PMID 31760044. S2CID 209493576.

- ^ Balaguer P, Delfosse V, Grimaldi M, Bourguet W (1 September 2017). "Structural and functional evidences for the interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and endocrine disruptors at low doses". Comptes Rendus Biologies. Endocrine disruptors / Les perturbateurs endocriniens. 340 (9–10): 414–420. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2017.08.002. PMID 29126514.

- ^ Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA (February 2003). "Toxicology rethinks its central belief". Nature. 421 (6924): 691–2. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..691C. doi:10.1038/421691a. PMID 12610596. S2CID 4419048.

- ^ Steeger T, Tietge J (29 May 2003). White Paper on Potential Developmental Effects of Atrazine on Amphibians (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2004.

- ^ Talsness CE, Kuriyama SN, Sterner-Kock A, Schnitker P, Grande SW, Shakibaei M, et al. (March 2008). "In utero and lactational exposures to low doses of polybrominated diphenyl ether-47 alter the reproductive system and thyroid gland of female rat offspring". Environmental Health Perspectives. 116 (3): 308–14. Bibcode:2008EnvHP.116..308T. doi:10.1289/ehp.10536. PMC 2265047. PMID 18335096.

- ^ Hayes TB, Case P, Chui S, Chung D, Haeffele C, Haston K, et al. (April 2006). "Pesticide mixtures, endocrine disruption, and amphibian declines: are we underestimating the impact?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (S–1): 40–50. Bibcode:2006EnvHP.114S..40H. doi:10.1289/ehp.8051. PMC 1874187. PMID 16818245.

- ^ Curwood S, Young J (4 September 2009). "Low Dose Makes the Poison". Living on Earth.

- ^ a b c Fürst P (October 2006). "Dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls and other organohalogen compounds in human milk. Levels, correlations, trends and exposure through breastfeeding". Mol Nutr Food Res. 50 (10): 922–33. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200600008. PMID 17009213.

- ^ Schecter A, Päpke O, Tung KC, Staskal D, Birnbaum L (October 2004). "Polybrominated diphenyl ethers contamination of United States food". Environ. Sci. Technol. 38 (20): 5306–11. Bibcode:2004EnST...38.5306S. doi:10.1021/es0490830. PMID 15543730.

- ^ Hites RA, Foran JA, Carpenter DO, Hamilton MC, Knuth BA, Schwager SJ (January 2004). "Global assessment of organic contaminants in farmed salmon". Science. 303 (5655): 226–9. Bibcode:2004Sci...303..226H. doi:10.1126/science.1091447. PMID 14716013. S2CID 24058620.

- ^ a b Aldegunde-Louzao N, Lolo-Aira M, Herrero-Latorre C (June 2024). "Phthalate esters in clothing: A review". Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 108 104457. Bibcode:2024EnvTP.10804457A. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2024.104457. hdl:10347/34744. PMID 38677495.

- ^ a b Ercan O, Tarcin G (1 December 2022). "Overview on Endocrine disruptors in food and their effects on infant's health". Global Pediatrics. 2 100019. doi:10.1016/j.gpeds.2022.100019. ISSN 2667-0097.

- ^ da Silva Costa R, Sainara Maia Fernandes T, de Sousa Almeida E, Tomé Oliveira J, Carvalho Guedes JA, Julião Zocolo G, et al. (8 April 2021). "Potential risk of BPA and phthalates in commercial water bottles: a minireview". Journal of Water and Health. 19 (3): 411–435. Bibcode:2021JWH....19..411D. doi:10.2166/wh.2021.202. ISSN 1477-8920. PMID 34152295.

- ^ Ercan O, Tarcin G (1 December 2022). "Overview on Endocrine disruptors in food and their effects on infant's health". Global Pediatrics. 2 100019. doi:10.1016/j.gpeds.2022.100019. ISSN 2667-0097.

- ^ Weschler CJ (2009). "Changes in indoor pollutants since the 1950s". Atmospheric Environment. 43 (1): 153–169. Bibcode:2009AtmEn..43..153W. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.044.

- ^ Rudel RA, Seryak LM, Brody JG (2008). "PCB-containing wood floor finish is a likely source of elevated PCBs in residents' blood, household air and dust: a case study of exposure". Environ Health. 7 (1) 2. Bibcode:2008EnvHe...7....2R. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-7-2. PMC 2267460. PMID 18201376.

- ^ Stapleton HM, Dodder NG, Offenberg JH, Schantz MM, Wise SA (February 2005). "Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in house dust and clothes dryer lint". Environ. Sci. Technol. 39 (4): 925–31. Bibcode:2005EnST...39..925S. doi:10.1021/es0486824. PMID 15773463.

- ^ Anderson HA, Imm P, Knobeloch L, Turyk M, Mathew J, Buelow C, et al. (September 2008). "Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) in serum: findings from a US cohort of consumers of sport-caught fish". Chemosphere. 73 (2): 187–94. Bibcode:2008Chmsp..73..187A. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.05.052. PMID 18599108.

- ^ Morland KB, Landrigan PJ, Sjödin A, Gobeille AK, Jones RS, McGahee EE, et al. (December 2005). "Body burdens of polybrominated diphenyl ethers among urban anglers". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (12): 1689–92. Bibcode:2005EnvHP.113.1689M. doi:10.1289/ehp.8138. PMC 1314906. PMID 16330348.

- ^ Lorber M (January 2008). "Exposure of Americans to polybrominated diphenyl ethers". J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 18 (1): 2–19. Bibcode:2008JESEE..18....2L. doi:10.1038/sj.jes.7500572. PMID 17426733.

- ^ Charney E, Sayre J, Coulter M (February 1980). "Increased lead absorption in inner city children: where does the lead come from?". Pediatrics. 65 (2): 226–31. doi:10.1542/peds.65.2.226. PMID 7354967.

- ^ Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA (March 2012). "Endocrine Disruptors and Asthma-Associated Chemicals in Consumer Products". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (7): 935–943. Bibcode:2012EnvHP.120..935D. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104052. PMC 3404651. PMID 22398195.

- Lay summary in: Olver C (5 April 2012). "Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products". Journalist's Resource.

- ^ Martina CA, Weiss B, Swan SH (June 2012). "Lifestyle behaviors associated with exposures to endocrine disruptors". Neurotoxicology. 33 (6): 1427–1433. Bibcode:2012NeuTx..33.1427M. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2012.05.016. PMC 3641683. PMID 22739065.

- Lay summary in: "Simpler lifestyle found to reduce exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals". Science Daily (Press release). 26 June 2012.

- ^ Brigden K, Hetherington S, Wang M, Santillo D, Johnston P (June 2013). "Hazardous chemicals in branded textile products on sale in 25 countries/regions during 2013" (PDF). Greenpeace Research Laboratories (published December 2013).

- ^ Cobbing M, Brodde K (May 2014). "A Red Card for sportswear brands" (PDF). Greenpeace e.V.

- ^ Li HL, Ma WL, Liu LY, Zhang Z, Sverko E, Zhang ZF, et al. (September 2019). "Phthalates in infant cotton clothing: Occurrence and implications for human exposure". The Science of the Total Environment. 683: 109–115. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.683..109L. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.132. PMID 31129321.

- ^ a b Tang Z, Chai M, Wang Y, Cheng J (April 2020). "Phthalates in preschool children's clothing manufactured in seven Asian countries: Occurrence, profiles and potential health risks". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 387 121681. Bibcode:2020JHzM..38721681T. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121681. PMID 31757725.

- ^ Mohapatra P, Gaonkar O (2021). An Overview of Chemicals in Textiles. Toxics Link (Report). New Delhi, India. p. 41.

- ^ Teuten EL, Saquing JM, Knappe DR, Barlaz MA, Jonsson S, Björn A, et al. (2009). "Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 2027–45. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0284. PMC 2873017. PMID 19528054.

- ^ "Endocrine disrupting chemicals, wildlife and the environment". CHEM Trust. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ Luo R, Zhang T, Wang L, Feng Y (1 November 2023). "Emissions and mitigation potential of endocrine disruptors during outdoor exercise: Fate, transport, and implications for human health". Environmental Research. 236 (Pt 2) 116575. Bibcode:2023ER....23616575L. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116575. ISSN 0013-9351. PMID 37487926.