Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Artificial cell

View on WikipediaAn artificial cell, synthetic cell or minimal cell is an engineered particle that mimics one or many functions of a biological cell. Often, artificial cells are biological or polymeric membranes which enclose biologically active materials.[1] As such, liposomes, polymersomes, nanoparticles, microcapsules and a number of other particles can qualify as artificial cells.

The terms "artificial cell" and "synthetic cell" are used in a variety of different fields and can have different meanings, as it is also reflected in the different sections of this article. Some stricter definitions are based on the assumption that the term "cell" directly relates to biological cells and that these structures therefore have to be alive (or part of a living organism) and, further, that the term "artificial" implies that these structures are artificially built from the bottom-up, i.e. from basic components. As such, in the area of synthetic biology, an artificial cell can be understood as a completely synthetically made cell that can capture energy, maintain ion gradients, contain macromolecules as well as store information and have the ability to replicate.[2] This kind of artificial cell has not yet been made.

However, in other cases, the term "artificial" does not imply that the entire structure is man-made, but instead, it can refer to the idea that certain functions or structures of biological cells can be modified, simplified, replaced or supplemented with a synthetic entity.

In other fields, the term "artificial cell" can refer to any compartment that somewhat resembles a biological cell in size or structure, but is synthetically made, or even fully made from non-biological components. The term "artificial cell" is also used for structures with direct applications such as compartments for drug delivery. Micro-encapsulation allows for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it.[3][4] The main advantages of encapsulation include improved mimicry in the body, increased solubility of the cargo and decreased immune responses. Notably, artificial cells have been clinically successful in hemoperfusion.[5]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Synthetic biology |

|---|

| Synthetic biological circuits |

| Genome editing |

| Artificial cells |

| Xenobiology |

| Other topics |

Bottom-up engineering of living artificial cells

[edit]

The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow brought forward the idea that not only does life arise from cells, but every cell comes from another cell; "Omnis cellula e cellula".[6] Until now, most attempts to create an artificial cell have engineered modules that can mimic certain functions of living cells. Advances in cell-free transcription and translation reactions allow the expression of many genes as well as interdependent genetic and metabolic networks,[7] but these efforts are still far from producing a fully operational cell.

A bottom-up approach to build an artificial cell would involve creating a protocell de novo, entirely from non-living materials. As the term "cell" implies, one prerequisite is the generation of some sort of compartment that defines an individual, cellular unit. Phospholipid membranes are an obvious choice as compartmentalizing boundaries,[8] as they act as selective barriers in all living biological cells. Scientists can encapsulate biomolecules in cell-sized phospholipid vesicles and by doing so, observe these molecules to act similarly as in biological cells and thereby recreate certain cell functions.[9] In a similar way, functional biological building blocks can be encapsulated in these lipid compartments to achieve the synthesis of (however rudimentary) artificial cells.

In addition to lipid-based structures, membraneless compartments have been engineered using liquid-liquid phase separation of RNAs, enabling spatial organization in prokaryotic cells similar to eukaryotic organelles. PandaPure technology utilizes addressable phase-separated RNA condensates to create synthetic organelles in bacterial cells, allowing for the simultaneous expression and purification of recombinant proteins through biomimetic sorting mechanisms that bypass conventional purification methods.[10][11]

It is proposed to create a phospholipid bilayer vesicle with DNA capable of self-reproducing using synthetic genetic information. The three primary elements of such artificial cells are the formation of a lipid membrane, DNA and RNA replication through a template process and the harvesting of chemical energy for active transport across the membrane.[12][13] The main hurdles foreseen and encountered with this proposed protocell are the creation of a minimal synthetic DNA that holds all sufficient information for life, and the reproduction of non-genetic components that are integral in cell development such as molecular self-organization.[14] However, it is hoped that this kind of bottom-up approach would provide insight into the fundamental questions of organizations at the cellular level and the origins of biological life. So far, no completely artificial cell capable of self-reproduction has been synthesized using the molecules of life, and this objective is still in a distant future although various groups are currently working towards this goal.[15]

Another method proposed to create a protocell more closely resembles the conditions believed to have been present during evolution known as the primordial soup. Various RNA polymers could be encapsulated in vesicles and in such small boundary conditions, chemical reactions would be tested for.[16]

Ethics and controversy

[edit]Protocell research has created controversy and opposing opinions, including critics of the vague definition of "artificial life".[17] The creation of a basic unit of life is the most pressing ethical concern.[18] Synthetic organisms could escape and cause damage to human health and ecosystems, or the technology could be used to make a biological weapon.[19] Cells with certain non-standard biochemistries, such as mirror life, could also have a competitive advantage over natural organisms.[20]

International Research Community

[edit]In the mid-2010s the research community started recognising the need to unify the field of synthetic cell research, acknowledging that the task of constructing an entire living organism from non-living components was beyond the resources of a single country.[21]

In 2017 the NSF-funded international Build-a-Cell large-scale research collaboration for the construction of synthetic living cell was started,.[22] Build-a-Cell has conducted nine interdisciplinary workshopping events, open to all interested, to discuss and guide the future of the synthetic cell community. Build-a-Cell was followed by national synthetic cell organizations in several other countries. Those national organizations include FabriCell,[23] MaxSynBio[24] and BaSyC.[25] The European synthetic cell efforts were unified in 2019 as SynCellEU initiative.[26]

Top-down approach to create a minimal living cell

[edit]Members from the J. Craig Venter Institute have used a top-down computational approach to knock out genes in a living organism to a minimum set of genes.[27] In 2010, the team succeeded in creating a replicating strain (named Mycoplasma laboratorium) of Mycoplasma mycoides using synthetically created DNA deemed to be the minimum requirement for life which was inserted into a genomically empty bacterium.[27] It is hoped that the process of top-down biosynthesis will enable the insertion of new genes that would perform profitable functions such as generation of hydrogen for fuel or capturing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.[18] The myriad regulatory, metabolic, and signaling networks are not completely characterized. These top-down approaches have limitations for the understanding of fundamental molecular regulation, since the host organisms have a complex and incompletely defined molecular composition.[28] In 2019 a complete computational model of all pathways in Mycoplasma Syn3.0 cell was published, representing the first complete in silico model for a living minimal organism.[29]

Heavy investing in biology has been done by large companies such as ExxonMobil, who has partnered with Synthetic Genomics Inc; Craig Venter's own biosynthetics company in the development of fuel from algae.[30]

As of 2016, Mycoplasma genitalium is the only organism used as a starting point for engineering a minimal cell, since it has the smallest known genome that can be cultivated under laboratory conditions; the wild-type variety has 482, and removing exactly 100 genes deemed non-essential resulted in a viable strain with improved growth rates. Reduced-genome Escherichia coli is considered more useful, and viable strains have been developed with 15% of the genome removed.[31]: 29–30

A variation of an artificial cell has been created in which a completely synthetic genome was introduced to genomically emptied host cells.[27] Although not completely artificial because the cytoplasmic components as well as the membrane from the host cell are kept, the engineered cell is under control of a synthetic genome and is able to replicate.

Artificial cells for medical applications

[edit]

History

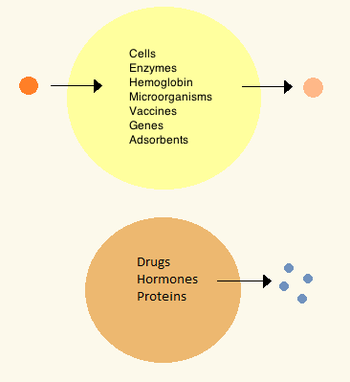

[edit]In the 1960s Thomas Chang developed microcapsules which he would later call "artificial cells", as they were cell-sized compartments made from artificial materials.[32] These cells consisted of ultrathin membranes of nylon, collodion or crosslinked protein whose semipermeable properties allowed diffusion of small molecules in and out of the cell. These cells were micron-sized and contained cells, enzymes, hemoglobin, magnetic materials, adsorbents and proteins.[3]

Later artificial cells have ranged from hundred-micrometer to nanometer dimensions and can carry microorganisms, vaccines, genes, drugs, hormones and peptides.[3] The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal.[33]

In the 1970s, researchers were able to introduce enzymes, proteins and hormones to biodegradable microcapsules, later leading to clinical use in diseases such as Lesch–Nyhan syndrome.[34] Although Chang's initial research focused on artificial red blood cells, only in the mid-1990s were biodegradable artificial red blood cells developed.[35] Artificial cells in biological cell encapsulation were first used in the clinic in 1994 for treatment in a diabetic patient[36] and since then other types of cells such as hepatocytes, adult stem cells and genetically engineered cells have been encapsulated and are under study for use in tissue regeneration.[37][38]

Materials

[edit]

Membranes for artificial cells can be made of simple polymers, crosslinked proteins, lipid membranes or polymer-lipid complexes. Further, membranes can be engineered to present surface proteins such as albumin, antigens, Na/K-ATPase carriers, or pores such as ion channels. Commonly used materials for the production of membranes include hydrogel polymers such as alginate, cellulose and thermoplastic polymers such as hydroxyethyl methacrylate-methyl methacrylate (HEMA- MMA), polyacrylonitrile-polyvinyl chloride (PAN-PVC), as well as variations of the above-mentioned.[4] The material used determines the permeability of the cell membrane, which for polymer depends on the is important in determining adequate diffusion of nutrients, waste and other critical molecules. Hydrophilic polymers have the potential to be biocompatible and can be fabricated into a variety of forms which include polymer micelles, sol-gel mixtures, physical blends and crosslinked particles and nanoparticles.[4] Of special interest are stimuli-responsive polymers that respond to pH or temperature changes for the use in targeted delivery. These polymers may be administered in the liquid form through a macroscopic injection and solidify or gel in situ because of the difference in pH or temperature. Nanoparticle and liposome preparations are also routinely used for material encapsulation and delivery. A major advantage of liposomes is their ability to fuse to cell and organelle membranes.

Preparation

[edit]Many variations for artificial cell preparation and encapsulation have been developed. Typically, vesicles such as a nanoparticle, polymersome or liposome are synthesized. An emulsion is typically made through the use of high pressure equipment such as a high pressure homogenizer or a Microfluidizer. Two micro-encapsulation methods for nitrocellulose are also described below.

High-pressure homogenization

[edit]In a high-pressure homogenizer, two liquids in oil/liquid suspension are forced through a small orifice under very high pressure. This process divides the products and allows the creation of extremely fine particles, as small as 1 nm.

Microfluidization

[edit]This technique uses a patented Microfluidizer to obtain a greater amount of homogenous suspensions that can create smaller particles than homogenizers. A homogenizer is first used to create a coarse suspension which is then pumped into the microfluidizer under high pressure. The flow is then split into two streams which will react at very high velocities in an interaction chamber until desired particle size is obtained.[39] This technique allows for large scale production of phospholipid liposomes and subsequent material nanoencapsulations.

Drop method

[edit]In this method, a cell solution is incorporated dropwise into a collodion solution of cellulose nitrate. As the drop travels through the collodion, it is coated with a membrane thanks to the interfacial polymerization properties of the collodion. The cell later settles into paraffin, where the membrane sets, which is then suspended using a saline solution. The drop method is used for the creation of large artificial cells which encapsulate biological cells, stem cells and genetically engineered stem cells.

Emulsion method

[edit]The emulsion method differs in that the material to be encapsulated is usually smaller and is placed in the bottom of a reaction chamber where the collodion is added on top and centrifuged, or otherwise disturbed in order to create an emulsion. The encapsulated material is then dispersed and suspended in saline solution.

Clinical relevance

[edit]Drug release and delivery

[edit]Artificial cells used for drug delivery differ from other artificial cells since their contents are intended to diffuse out of the membrane, or be engulfed and digested by a host target cell. Often used are submicron, lipid membrane artificial cells that may be referred to as nanocapsules, nanoparticles, polymersomes, or other variations of the term.[40]

A temperature-responsive system has been developed to use RNA thermometers to control the timing and location of cargo release from artificial cells.[41] This is done by having artificial cells express a pore forming protein - alpha hemolysin - under the control of an RNA thermometer, allowing for cargo release to be coupled to temperature changes.[41]

Enzyme therapy

[edit]Enzyme therapy is being actively studied for genetic metabolic diseases where an enzyme is over-expressed, under-expressed, defective, or not at all there. In the case of under-expression or expression of a defective enzyme, an active form of the enzyme is introduced in the body to compensate for the deficit. On the other hand, an enzymatic over-expression may be counteracted by introduction of a competing non-functional enzyme; that is, an enzyme which metabolizes the substrate into non-active products. When placed within an artificial cell, enzymes can carry out their function for a much longer period compared to free enzymes[3] and can be further optimized by polymer conjugation.[42]

The first enzyme studied under artificial cell encapsulation was asparaginase for the treatment of lymphosarcoma in mice. This treatment delayed the onset and growth of the tumor.[43] These initial findings led to further research in the use of artificial cells for enzyme delivery in tyrosine dependent melanomas.[44] These tumors have a higher dependency on tyrosine than normal cells for growth, and research has shown that lowering systemic levels of tyrosine in mice can inhibit growth of melanomas.[45] The use of artificial cells in the delivery of tyrosinase; and enzyme that digests tyrosine, allows for better enzyme stability and is shown effective in the removal of tyrosine without the severe side-effects associated with tyrosine deprivation in the diet.[46]

Artificial cell enzyme therapy is also of interest for the activation of prodrugs such as ifosfamide in certain cancers. Artificial cells encapsulating the cytochrome p450 enzyme which converts this prodrug into the active drug can be tailored to accumulate in the pancreatic carcinoma or implanting the artificial cells close to the tumor site. Here, the local concentration of the activated ifosfamide will be much higher than in the rest of the body thus preventing systemic toxicity.[47] The treatment was successful in animals[48] and showed a doubling in median survivals amongst patients with advanced-stage pancreatic cancer in phase I/II clinical trials, and a tripling in one-year survival rate.[47]

Gene therapy

[edit]In treatment of genetic diseases, gene therapy aims to insert, alter or remove genes within an afflicted individual's cells. The technology relies heavily on viral vectors which raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis and systemic immune response that have led to human deaths[49][50] and development of leukemia[51][52] in clinical trials. Circumventing the need for vectors by using naked or plasmid DNA as its own delivery system also encounters problems such as low transduction efficiency and poor tissue targeting when given systemically.[4]

Artificial cells have been proposed as a non-viral vector by which genetically modified non-autologous cells are encapsulated and implanted to deliver recombinant proteins in vivo.[53] This type of immuno-isolation has been proven efficient in mice through delivery of artificial cells containing mouse growth hormone which rescued a growth-retardation in mutant mice.[54] A few strategies have advanced to human clinical trials for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, lateral sclerosis and pain control.[4]

Hemoperfusion

[edit]The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal.[33] Activated charcoal has the capability of adsorbing many large molecules and has for a long time been known for its ability to remove toxic substances from the blood in accidental poisoning or overdose. However, perfusion through direct charcoal administration is toxic as it leads to embolisms and damage of blood cells followed by removal by platelets.[55] Artificial cells allow toxins to diffuse into the cell while keeping the dangerous cargo within their ultrathin membrane.[33]

Artificial cell hemoperfusion has been proposed as a less costly and more efficient detoxifying option than hemodialysis,[3] in which blood filtering takes place only through size separation by a physical membrane. In hemoperfusion, thousands of adsorbent artificial cells are retained inside a small container through the use of two screens on either end through which patient blood perfuses. As the blood circulates, toxins or drugs diffuse into the cells and are retained by the absorbing material. The membranes of artificial cells are much thinner those used in dialysis and their small size means that they have a high membrane surface area. This means that a portion of cell can have a theoretical mass transfer that is a hundredfold higher than that of a whole artificial kidney machine.[3] The device has been established as a routine clinical method for patients treated for accidental or suicidal poisoning but has also been introduced as therapy in liver failure and kidney failure by carrying out part of the function of these organs.[3] Artificial cell hemoperfusion has also been proposed for use in immunoadsorption through which antibodies can be removed from the body by attaching an immunoadsorbing material such as albumin on the surface of the artificial cells. This principle has been used to remove blood group antibodies from plasma for bone marrow transplantation[56] and for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia through monoclonal antibodies to remove low-density lipoproteins.[57] Hemoperfusion is especially useful in countries with a weak hemodialysis manufacturing industry as the devices tend to be cheaper there and used in kidney failure patients.

Encapsulated cells

[edit]

The most common method of preparation of artificial cells is through cell encapsulation. Encapsulated cells are typically achieved through the generation of controlled-size droplets from a liquid cell suspension which are then rapidly solidified or gelled to provide added stability. The stabilization may be achieved through a change in temperature or via material crosslinking.[4] The microenvironment that a cell sees changes upon encapsulation. It typically goes from being on a monolayer to a suspension in a polymer scaffold within a polymeric membrane. A drawback of the technique is that encapsulating a cell decreases its viability and ability to proliferate and differentiate.[58] Further, after some time within the microcapsule, cells form clusters that inhibit the exchange of oxygen and metabolic waste,[59] leading to apoptosis and necrosis thus limiting the efficacy of the cells and activating the host's immune system. Artificial cells have been successful for transplanting a number of cells including islets of Langerhans for diabetes treatment,[60] parathyroid cells and adrenal cortex cells.

Encapsulated hepatocytes

[edit]Shortage of organ donors make artificial cells key players in alternative therapies for liver failure. The use of artificial cells for hepatocyte transplantation has demonstrated feasibility and efficacy in providing liver function in models of animal liver disease and bioartificial liver devices.[61] Research stemmed off experiments in which the hepatocytes were attached to the surface of a micro-carriers[62] and has evolved into hepatocytes which are encapsulated in a three-dimensional matrix in alginate microdroplets covered by an outer skin of polylysine. A key advantage to this delivery method is the circumvention of immunosuppression therapy for the duration of the treatment. Hepatocyte encapsulations have been proposed for use in a bioartificial liver. The device consists of a cylindrical chamber imbedded with isolated hepatocytes through which patient plasma is circulated extra-corporeally in a type of hemoperfusion. Because microcapsules have a high surface area to volume ratio, they provide large surface for substrate diffusion and can accommodate a large number of hepatocytes. Treatment to induced liver failure mice showed a significant increase in the rate of survival.[61] Artificial liver systems are still in early development but show potential for patients waiting for organ transplant or while a patient's own liver regenerates sufficiently to resume normal function. So far, clinical trials using artificial liver systems and hepatocyte transplantation in end-stage liver diseases have shown improvement of health markers but have not yet improved survival.[63] The short longevity and aggregation of artificial hepatocytes after transplantation are the main obstacles encountered. Hepatocytes co-encapsulated with stem cells show greater viability in culture and after implantation[64] and implantation of artificial stem cells alone have also shown liver regeneration.[65] As such interest has arisen in the use of stem cells for encapsulation in regenerative medicine.

Encapsulated bacterial cells

[edit]The oral ingestion of live bacterial cell colonies has been proposed and is currently in therapy for the modulation of intestinal microflora,[66] prevention of diarrheal diseases,[67] treatment of H. Pylori infections, atopic inflammations,[68] lactose intolerance[69] and immune modulation,[70] amongst others. The proposed mechanism of action is not fully understood but is believed to have two main effects. The first is the nutritional effect, in which the bacteria compete with toxin producing bacteria. The second is the sanitary effect, which stimulates resistance to colonization and stimulates immune response.[4] The oral delivery of bacterial cultures is often a problem because they are targeted by the immune system and often destroyed when taken orally. Artificial cells help address these issues by providing mimicry into the body and selective or long term release thus increasing the viability of bacteria reaching the gastrointestinal system.[4] In addition, live bacterial cell encapsulation can be engineered to allow diffusion of small molecules including peptides into the body for therapeutic purposes.[4] Membranes that have proven successful for bacterial delivery include cellulose acetate and variants of alginate.[4] Additional uses that have arisen from encapsulation of bacterial cells include protection against challenge from M. Tuberculosis[71] and upregulation of Ig secreting cells from the immune system.[72] The technology is limited by the risk of systemic infections, adverse metabolic activities and the risk of gene transfer.[4] However, the greater challenge remains the delivery of sufficient viable bacteria to the site of interest.[4]

Artificial blood cells as oxygen carriers

[edit]Nano sized oxygen carriers are used as a type of red blood cell substitutes, although they lack other components of red blood cells. They are composed of a synthetic polymersome or an artificial membrane surrounding purified animal, human or recombinant hemoglobin.[73] Overall, hemoglobin delivery continues to be a challenge because it is highly toxic when delivered without any modifications. In some clinical trials, vasopressor effects have been observed.[74][75]

Artificial red blood cells

[edit]Research interest in the use of artificial cells for blood arose after the AIDS scare of the 1980s. Besides bypassing the potential for disease transmission, artificial red blood cells are desired because they eliminate drawbacks associated with allogenic blood transfusions such as blood typing, immune reactions and its short storage life of 42 days. A hemoglobin substitute may be stored at room temperature and not under refrigeration for more than a year.[3] Attempts have been made to develop a complete working red blood cell which comprises carbonic not only an oxygen carrier but also the enzymes associated with the cell. The first attempt was made in 1957 by replacing the red blood cell membrane by an ultrathin polymeric membrane[76] which was followed by encapsulation through a lipid membrane[77] and more recently a biodegradable polymeric membrane.[3] A biological red blood cell membrane including lipids and associated proteins can also be used to encapsulate nanoparticles and increase residence time in vivo by bypassing macrophage uptake and systemic clearance.[78]

Artificial leuko-polymersomes

[edit]A leuko-polymersome is a polymersome engineered to have the adhesive properties of a leukocyte.[79] Polymersomes are vesicles composed of a bilayer sheet that can encapsulate many active molecules such as drugs or enzymes. By adding the adhesive properties of a leukocyte to their membranes, they can be made to slow down, or roll along epithelial walls within the quickly flowing circulatory system.

Unconventional types of artificial cells

[edit]Electronic artificial cell

[edit]The concept of an Electronic Artificial Cell has been expanded in a series of 3 EU projects coordinated by John McCaskill from 2004 to 2015.

The European Commission sponsored the development of the Programmable Artificial Cell Evolution (PACE) program[80] from 2004 to 2008 whose goal was to lay the foundation for the creation of "microscopic self-organizing, self-replicating, and evolvable autonomous entities built from simple organic and inorganic substances that can be genetically programmed to perform specific functions"[80] for the eventual integration into information systems. The PACE project developed the first Omega Machine, a microfluidic life support system for artificial cells that could complement chemically missing functionalities (as originally proposed by Norman Packard, Steen Rasmussen, Mark Beadau and John McCaskill). The ultimate aim was to attain an evolvable hybrid cell in a complex microscale programmable environment. The functions of the Omega Machine could then be removed stepwise, posing a series of solvable evolution challenges to the artificial cell chemistry. The project achieved chemical integration up to the level of pairs of the three core functions of artificial cells (a genetic subsystem, a containment system and a metabolic system), and generated novel spatially resolved programmable microfluidic environments for the integration of containment and genetic amplification.[80] The project led to the creation of the European center for living technology.[81]

Following this research, in 2007, John McCaskill proposed to concentrate on an electronically complemented artificial cell, called the Electronic Chemical Cell. The key idea was to use a massively parallel array of electrodes coupled to locally dedicated electronic circuitry, in a two-dimensional thin film, to complement emerging chemical cellular functionality. Local electronic information defining the electrode switching and sensing circuits could serve as an electronic genome, complementing the molecular sequential information in the emerging protocols. A research proposal was successful with the European Commission and an international team of scientists partially overlapping with the PACE consortium commenced work 2008–2012 on the project Electronic Chemical Cells. The project demonstrated among other things that electronically controlled local transport of specific sequences could be used as an artificial spatial control system for the genetic proliferation of future artificial cells, and that core processes of metabolism could be delivered by suitably coated electrode arrays.

The major limitation of this approach, apart from the initial difficulties in mastering microscale electrochemistry and electrokinetics, is that the electronic system is interconnected as a rigid non-autonomous piece of macroscopic hardware. In 2011, McCaskill proposed to invert the geometry of electronics and chemistry : instead of placing chemicals in an active electronic medium, to place microscopic autonomous electronics in a chemical medium. He organized a project to tackle a third generation of Electronic Artificial Cells at the 100 μm scale that could self-assemble from two half-cells "lablets" to enclose an internal chemical space, and function with the aid of active electronics powered by the medium they are immersed in. Such cells can copy both their electronic and chemical contents and will be capable of evolution within the constraints provided by their special pre-synthesized microscopic building blocks. In September 2012 work commenced on this project.[82]

Artificial neurons

[edit]There is research and development into physical artificial neurons – organic and inorganic.

For example, some artificial neurons can receive[83][84] and release dopamine (chemical signals rather than electrical signals) and communicate with natural rat muscle and brain cells, with potential for use in BCIs/prosthetics.[85][86]

Low-power biocompatible memristors may enable construction of artificial neurons which function at voltages of biological action potentials and could be used to directly process biosensing signals, for neuromorphic computing and/or direct communication with biological neurons.[87][88][89]

Organic neuromorphic circuits made out of polymers, coated with an ion-rich gel to enable a material to carry an electric charge like real neurons, have been built into a robot, enabling it to learn sensorimotorically within the real world, rather than via simulations or virtually.[90][91] Moreover, artificial spiking neurons made of soft matter (polymers) can operate in biologically relevant environments and enable the synergetic communication between the artificial and biological domains.[92][93]Jeewanu

[edit]Jeewanu protocells are synthetic chemical particles that possess cell-like structure and seem to have some functional living properties.[94] First synthesized in 1963 from simple minerals and basic organics while exposed to sunlight, it is still reported to have some metabolic capabilities, the presence of semipermeable membrane, amino acids, phospholipids, carbohydrates and RNA-like molecules.[94] However, the nature and properties of the Jeewanu remains to be clarified.[94][95]

Semi-artificial cyborg cells

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Buddingh' BC, van Hest JC (April 2017). "Artificial Cells: Synthetic Compartments with Life-like Functionality and Adaptivity". Accounts of Chemical Research. 50 (4): 769–777. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00512. PMC 5397886. PMID 28094501.

- ^ Deamer D (July 2005). "A giant step towards artificial life?". Trends in Biotechnology. 23 (7): 336–338. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.05.008. PMID 15935500.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chang TM (2007). Artificial cells : biotechnology, nanomedicine, regenerative medicine, blood substitutes, bioencapsulation, cell/stem cell therapy. Hackensack, N.J.: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-270-576-1.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Prakash S (2007). Artificial cells, cell engineering and therapy. Boca Raton, Fl: Woodhead Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84569-036-6.

- ^ Gebelein CG (1983). Polymeric materials and artificial organs based on a symposium sponsored by the Division of Organic Coatings and Plastics Chemistry at the 185th Meeting of the American Chemical Society. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society. ISBN 978-0-8412-1084-4.[page needed]

- ^ Virchow RL (1858). Die cellularpathologie in ihrer begründung auf physiologische und pathologische gewebelehre [Cellular pathology in its justification of physiological and pathological histology]. Zwanzig Vorlesungen gehalten wahrend der Monate Februar, Marz und April 1858 (in German). Berlin: Verlag von August Hirschwald. p. xv.

- ^ Giaveri, Simone; Bohra, Nitin; Diehl, Christoph; Yang, Hao Yuan; Ballinger, Martine; Paczia, Nicole; Glatter, Timo; Erb, Tobias J. (2024-07-12). "Integrated translation and metabolism in a partially self-synthesizing biochemical network". Science. 385 (6705): 174–178. doi:10.1126/science.adn3856.

- ^ Kamiya K, Takeuchi S (August 2017). "Giant liposome formation toward the synthesis of well-defined artificial cells". Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 5 (30): 5911–5923. doi:10.1039/C7TB01322A. PMID 32264347.

- ^ Litschel T, Schwille P (May 2021). "Protein Reconstitution Inside Giant Unilamellar Vesicles". Annual Review of Biophysics. 50: 525–548. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-100620-114132. PMID 33667121. S2CID 232131463.

- ^ Barnes, Natalie G. (2022-11-08). "Organelle-like scaffolds in bacteria for synthetic biology". Nature Biotechnology. 40 (11): 1574–1574. doi:10.1038/s41587-022-01569-8. ISSN 1546-1696.

- ^ Guo, Haotian; Chen, Jionglin (2024-05-21), Synthetic organelles enable protein purification in a single operation, bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2024.05.17.594729, retrieved 2025-08-20

- ^ Szostak JW, Bartel DP, Luisi PL (January 2001). "Synthesizing life". Nature. 409 (6818): 387–390. doi:10.1038/35053176. PMID 11201752. S2CID 4429162.

- ^ Pohorille A, Deamer D (March 2002). "Artificial cells: prospects for biotechnology". Trends in Biotechnology. 20 (3): 123–128. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01909-1. hdl:2060/20020043286. PMID 11841864.

- ^ Noireaux V, Maeda YT, Libchaber A (March 2011). "Development of an artificial cell, from self-organization to computation and self-reproduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (9): 3473–3480. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.3473N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017075108. PMC 3048108. PMID 21317359.

- ^ Rasmussen S, Chen L, Nilsson M, Abe S (Summer 2003). "Bridging nonliving and living matter". Artificial Life. 9 (3): 269–316. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.101.1606. doi:10.1162/106454603322392479. PMID 14556688. S2CID 6076707.

- ^ Gilbert W (20 February 1986). "Origin of life: The RNA world". Nature. 319 (6055): 618. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..618G. doi:10.1038/319618a0. S2CID 8026658.

- ^ Bedau M, Church G, Rasmussen S, Caplan A, Benner S, Fussenegger M, et al. (May 2010). "Life after the synthetic cell". Nature. 465 (7297): 422–424. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..422.. doi:10.1038/465422a. PMID 20495545. S2CID 27471255.

- ^ a b Parke EC (2009). Beadau MA (ed.). The ethics of protocells moral and social implications of creating life in the laboratory ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51269-5.

- ^ Stuart Fox (27 May 2010). "Is Synthetic Life Dangerous?". livescience.com. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Adamala, Katarzyna P.; Agashe, Deepa; Belkaid, Yasmine; Bittencourt, Daniela Matias de C.; Cai, Yizhi; Chang, Matthew W.; Chen, Irene A.; Church, George M.; Cooper, Vaughn S.; Davis, Mark M.; Devaraj, Neal K.; Endy, Drew; Esvelt, Kevin M.; Glass, John I.; Hand, Timothy W. (2024-12-12). "Confronting risks of mirror life". Science. 386 (6728): 1351–1353. doi:10.1126/science.ads9158. PMID 39666824.

- ^ Swetlitz, Ike (28 July 2017). "From chemicals to life: Scientists try to build cells from scratch". Stat. Retrieved 4 Dec 2019.

- ^ "Build-a-Cell". Retrieved 4 Dec 2019.

- ^ "FabriCell". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ^ "MaxSynBio - Max Planck Research Network in Synthetic Biology". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ^ "BaSyC". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ^ "SynCell EU". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ^ a b c Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, et al. (July 2010). "Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome". Science. 329 (5987): 52–56. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...52G. doi:10.1126/science.1190719. PMID 20488990. S2CID 7320517.

- ^ Armstrong R (September 2014). "Designing with protocells: applications of a novel technical platform". Life. 4 (3): 457–490. Bibcode:2014Life....4..457A. doi:10.3390/life4030457. PMC 4206855. PMID 25370381.

- ^ Breuer M, Earnest TM, Merryman C, Wise KS, Sun L, Lynott MR, et al. (January 2019). "Essential metabolism for a minimal cell". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.36842. PMC 6609329. PMID 30657448.

- ^ Sheridan C (September 2009). "Big oil bucks for algae". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (9): 783. doi:10.1038/nbt0909-783. PMID 19741613. S2CID 205270805.

- ^ EU Directorate-General for Health and Consumers (2016-02-12). Opinion on synthetic biology II: Risk assessment methodologies and safety aspects. Publications Office. doi:10.2772/63529. ISBN 9789279439162.

- ^ Chang TM (October 1964). "Semipermeable Microcapsules". Science. 146 (3643): 524–525. Bibcode:1964Sci...146..524C. doi:10.1126/science.146.3643.524. PMID 14190240. S2CID 40740134.

- ^ a b c Chang TM (1996). "Editorial: past, present and future perspectives on the 40th anniversary of hemoglobin based red blood cell substitutes". Artificial Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 24: ixxxvi. NAID 10005526771.

- ^ Palmour RM, Goodyer P, Reade T, Chang TM (September 1989). "Microencapsulated xanthine oxidase as experimental therapy in Lesch-Nyhan disease". Lancet. 2 (8664): 687–688. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90939-2. PMID 2570944. S2CID 39716068.

- ^ Chang TM (1997). Blood substitutes. Basel: Karger. ISBN 978-3-8055-6584-4.[page needed]

- ^ Soon-Shiong P, Heintz RE, Merideth N, Yao QX, Yao Z, Zheng T, et al. (April 1994). "Insulin independence in a type 1 diabetic patient after encapsulated islet transplantation". Lancet. 343 (8903): 950–951. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90067-1. PMID 7909011. S2CID 940319.

- ^ Liu ZC, Chang TM (June 2003). "Coencapsulation of hepatocytes and bone marrow stem cells: in vitro conversion of ammonia and in vivo lowering of bilirubin in hyperbilirubemia Gunn rats". The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 26 (6): 491–497. doi:10.1177/039139880302600607. PMID 12894754. S2CID 12447199.

- ^ Aebischer P, Schluep M, Déglon N, Joseph JM, Hirt L, Heyd B, et al. (June 1996). "Intrathecal delivery of CNTF using encapsulated genetically modified xenogeneic cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients". Nature Medicine. 2 (6): 696–699. doi:10.1038/nm0696-696. PMID 8640564. S2CID 8049662.

- ^ Vivier A, Vuillemard JC, Ackermann HW, Poncelet D (1992). "Large-scale blood substitute production using a microfluidizer". Biomaterials, Artificial Cells, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 20 (2–4): 377–397. doi:10.3109/10731199209119658. PMID 1391454.

- ^ Jakaria MG, Sorkhdini P, Yang D, Zhou Y, Meenach SA (February 2022). "Lung cell membrane-coated nanoparticles capable of enhanced internalization and translocation in pulmonary epithelial cells". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 613 121418. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121418. PMC 8792290. PMID 34954003.

- ^ a b Monck, Carolina; Elani, Yuval; Ceroni, Francesca (2024-07-05). "Genetically programmed synthetic cells for thermo-responsive protein synthesis and cargo release". Nature Chemical Biology. 20 (10): 1380–1386. doi:10.1038/s41589-024-01673-7. ISSN 1552-4469. PMC 11427347.

- ^ Park et al. 1981[full citation needed][page needed]

- ^ Chang TM (January 1971). "The in vivo effects of semipermeable microcapsules containing L-asparaginase on 6C3HED lymphosarcoma". Nature. 229 (5280): 117–118. Bibcode:1971Natur.229..117C. doi:10.1038/229117a0. PMID 4923094. S2CID 4261902.

- ^ Yu B, Chang TM (April 2004). "Effects of long-term oral administration of polymeric microcapsules containing tyrosinase on maintaining decreased systemic tyrosine levels in rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 93 (4): 831–837. doi:10.1002/jps.10593. PMID 14999721.

- ^ Meadows GG, Pierson HF, Abdallah RM, Desai PR (August 1982). "Dietary influence of tyrosine and phenylalanine on the response of B16 melanoma to carbidopa-levodopa methyl ester chemotherapy". Cancer Research. 42 (8): 3056–3063. PMID 7093952.

- ^ Chang TM (February 2004). "Artificial cell bioencapsulation in macro, micro, nano, and molecular dimensions: keynote lecture". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 32 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1081/bio-120028665. PMID 15027798. S2CID 37799530.

- ^ a b Löhr M, Hummel F, Faulmann G, Ringel J, Saller R, Hain J, et al. (May 2002). "Microencapsulated, CYP2B1-transfected cells activating ifosfamide at the site of the tumor: the magic bullets of the 21st century". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 49 (Suppl 1): S21 – S24. doi:10.1007/s00280-002-0448-0. PMID 12042985. S2CID 10329480.

- ^ Kröger JC, Benz S, Hoffmeyer A, Bago Z, Bergmeister H, Günzburg WH, et al. (1999). "Intra-arterial instillation of microencapsulated, Ifosfamide-activating cells in the pig pancreas for chemotherapeutic targeting". Pancreatology. 3 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1159/000069147. PMID 12649565. S2CID 23711385.

- ^ Carmen IH (April 2001). "A death in the laboratory: the politics of the Gelsinger aftermath". Molecular Therapy. 3 (4): 425–428. doi:10.1006/mthe.2001.0305. PMID 11319902.

- ^ Raper SE, Chirmule N, Lee FS, Wivel NA, Bagg A, Gao GP, et al. (1 September 2003). "Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 80 (1–2): 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.016. PMID 14567964.

- ^ Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, et al. (April 2000). "Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease". Science. 288 (5466): 669–672. Bibcode:2000Sci...288..669C. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.669. PMID 10784449.

- ^ Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. (October 2003). "LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1". Science. 302 (5644): 415–419. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..415H. doi:10.1126/science.1088547. PMID 14564000. S2CID 9100335.

- ^ Chang PL, Van Raamsdonk JM, Hortelano G, Barsoum SC, MacDonald NC, Stockley TL (February 1999). "The in vivo delivery of heterologous proteins by microencapsulated recombinant cells". Trends in Biotechnology. 17 (2): 78–83. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01250-5. PMID 10087608.

- ^ al-Hendy A, Hortelano G, Tannenbaum GS, Chang PL (February 1995). "Correction of the growth defect in dwarf mice with nonautologous microencapsulated myoblasts--an alternate approach to somatic gene therapy". Human Gene Therapy. 6 (2): 165–175. doi:10.1089/hum.1995.6.2-165. PMID 7734517.

- ^ Dunea G, Kolff WJ (1965). "Clinical Experience with the Yatzidis Charcoal Artificial Kidney". Transactions of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs. 11: 178–182. doi:10.1097/00002480-196504000-00035. PMID 14329080.

- ^ Bensinger WI, Buckner CD, Clift RA (1985). "Whole blood immunoadsorption of anti-A or anti-B antibodies". Vox Sanguinis. 48 (6): 357–361. doi:10.1111/j.1423-0410.1985.tb00196.x. PMID 3892895. S2CID 12777645.

- ^ Yang L, Cheng Y, Yan WR, Yu YT (2004). "Extracorporeal whole blood immunoadsorption of autoimmune myasthenia gravis by cellulose tryptophan adsorbent". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 32 (4): 519–528. doi:10.1081/bio-200039610. PMID 15974179. S2CID 7269229.

- ^ Chang PL (1994). "Calcium Phosphate-Mediated DNA Transfection". In Wolff JA (ed.). Gene Therapeutics. Boston: Birkhauser. pp. 157–179. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-6822-9_9. ISBN 978-1-4684-6822-9.

- ^ Ponce S, Orive G, Gascón AR, Hernández RM, Pedraz JL (April 2005). "Microcapsules prepared with different biomaterials to immobilize GDNF secreting 3T3 fibroblasts". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 293 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.028. PMID 15778039.

- ^ Kizilel S, Garfinkel M, Opara E (December 2005). "The bioartificial pancreas: progress and challenges". Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 7 (6): 968–985. doi:10.1089/dia.2005.7.968. PMID 16386103.

- ^ a b Dixit V, Gitnick G (27 November 2003). "The bioartificial liver: state-of-the-art". The European Journal of Surgery. Supplement. 164 (582): 71–76. doi:10.1080/11024159850191481. PMID 10029369.

- ^ Demetriou AA, Whiting JF, Feldman D, Levenson SM, Chowdhury NR, Moscioni AD, et al. (September 1986). "Replacement of liver function in rats by transplantation of microcarrier-attached hepatocytes". Science. 233 (4769): 1190–1192. Bibcode:1986Sci...233.1190D. doi:10.1126/science.2426782. PMID 2426782.

- ^ Sgroi A, Serre-Beinier V, Morel P, Bühler L (February 2009). "What clinical alternatives to whole liver transplantation? Current status of artificial devices and hepatocyte transplantation". Transplantation. 87 (4): 457–466. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181963ad3. PMID 19307780.

- ^ Liu ZC, Chang TM (March 2002). "Increased viability of transplanted hepatocytes when hepatocytes are co-encapsulated with bone marrow stem cells using a novel method". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 30 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1081/bio-120003191. PMID 12027231. S2CID 26667880.

- ^ Pedraz JL, Orive G, eds. (2010). Therapeutic applications of cell microencapsulation (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-5785-6.

- ^ Mattila-Sandholm T, Blum S, Collins JK, Crittenden R, De Vos W, Dunne C, et al. (1 December 1999). "Probiotics: towards demonstrating efficacy". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 10 (12): 393–399. doi:10.1016/S0924-2244(00)00029-7.

- ^ Huang JS, Bousvaros A, Lee JW, Diaz A, Davidson EJ (November 2002). "Efficacy of probiotic use in acute diarrhea in children: a meta-analysis". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 47 (11): 2625–2634. doi:10.1023/A:1020501202369. PMID 12452406. S2CID 207559325.

- ^ Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sütas Y, Moilanen E, Salminen S (November 2000). "Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 30 (11): 1604–1610. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00943.x. PMID 11069570. S2CID 13524021.

- ^ Lin MY, Yen CL, Chen SH (January 1998). "Management of lactose maldigestion by consuming milk containing lactobacilli". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 43 (1): 133–137. doi:10.1023/A:1018840507952. PMID 9508514. S2CID 22890925.

- ^ Gill HS (1 May 1998). "Stimulation of the Immune System by Lactic Cultures". International Dairy Journal. 8 (5–6): 535–544. doi:10.1016/S0958-6946(98)00074-0.

- ^ Aldwell FE, Tucker IG, de Lisle GW, Buddle BM (January 2003). "Oral delivery of Mycobacterium bovis BCG in a lipid formulation induces resistance to pulmonary tuberculosis in mice". Infection and Immunity. 71 (1): 101–108. doi:10.1128/IAI.71.1.101-108.2003. PMC 143408. PMID 12496154.

- ^ Park JH, Um JI, Lee BJ, Goh JS, Park SY, Kim WS, Kim PH (September 2002). "Encapsulated Bifidobacterium bifidum potentiates intestinal IgA production". Cellular Immunology. 219 (1): 22–27. doi:10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00579-8. PMID 12473264.

- ^ Kim HW, Greenburg AG (September 2004). "Artificial oxygen carriers as red blood cell substitutes: a selected review and current status". Artificial Organs. 28 (9): 813–828. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1594.2004.07345.x. PMID 15320945.

- ^ Nelson DJ (1998). "Blood and HemAssistTM (DCLHb): Potentially a complementary therapeutic team". In Chang TM (ed.). Blood Substitutes: Principles, Methods, Products and Clinical Trials. Vol. 2. Basel: Karger. pp. 39–57.

- ^ Burhop KE, Estep TE (2001). "Hemoglobin induced myocardial lesions". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 29 (2): 101–106. doi:10.1080/10731190108951271. PMC 3555357.

- ^ "30th Anniversary in Artificial Red Blood Cell Research". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 16 (1–3): 1–9. 1 January 1988. doi:10.3109/10731198809132551.

- ^ Djordjevich L, Miller IF (May 1980). "Synthetic erythrocytes from lipid encapsulated hemoglobin". Experimental Hematology. 8 (5): 584–592. PMID 7461058.

- ^ Hu CM, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang L (July 2011). "Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (27): 10980–10985. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810980H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106634108. PMC 3131364. PMID 21690347.

- ^ Hammer DA, Robbins GP, Haun JB, Lin JJ, Qi W, Smith LA, et al. (1 January 2008). "Leuko-polymersomes". Faraday Discussions. 139: 129–41, discussion 213–28, 419–20. Bibcode:2008FaDi..139..129H. doi:10.1039/B717821B. PMC 2714229. PMID 19048993.

- ^ a b c "Programmable Artificial Cell Evolution" (PACE)". PACE Consortium.

- ^ "European center for living technology". European Center for Living Technology. Archived from the original on 2011-12-14.

- ^ "Microscale Chemically Reactive Electronic Agents". Ruhr Universität Bochum.

- ^ Kleiner, Kurt (25 August 2022). "Making computer chips act more like brain cells". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-082422-1. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Keene, Scott T.; Lubrano, Claudia; Kazemzadeh, Setareh; Melianas, Armantas; Tuchman, Yaakov; Polino, Giuseppina; Scognamiglio, Paola; Cinà, Lucio; Salleo, Alberto; van de Burgt, Yoeri; Santoro, Francesca (September 2020). "A biohybrid synapse with neurotransmitter-mediated plasticity". Nature Materials. 19 (9): 969–973. Bibcode:2020NatMa..19..969K. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-0703-y. ISSN 1476-4660. PMID 32541935. S2CID 219691307.

- University press release: "Researchers develop artificial synapse that works with living cells". Stanford University via medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Artificial neuron swaps dopamine with rat brain cells like a real one". New Scientist. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Wang, Ting; Wang, Ming; Wang, Jianwu; Yang, Le; Ren, Xueyang; Song, Gang; Chen, Shisheng; Yuan, Yuehui; Liu, Ruiqing; Pan, Liang; Li, Zheng; Leow, Wan Ru; Luo, Yifei; Ji, Shaobo; Cui, Zequn; He, Ke; Zhang, Feilong; Lv, Fengting; Tian, Yuanyuan; Cai, Kaiyu; Yang, Bowen; Niu, Jingyi; Zou, Haochen; Liu, Songrui; Xu, Guoliang; Fan, Xing; Hu, Benhui; Loh, Xian Jun; Wang, Lianhui; Chen, Xiaodong (8 August 2022). "A chemically mediated artificial neuron". Nature Electronics. 5 (9): 586–595. doi:10.1038/s41928-022-00803-0. hdl:10356/163240. ISSN 2520-1131. S2CID 251464760.

- ^ "Scientists create tiny devices that work like the human brain". The Independent. April 20, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Researchers unveil electronics that mimic the human brain in efficient learning". phys.org. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Fu, Tianda; Liu, Xiaomeng; Gao, Hongyan; Ward, Joy E.; Liu, Xiaorong; Yin, Bing; Wang, Zhongrui; Zhuo, Ye; Walker, David J. F.; Joshua Yang, J.; Chen, Jianhan; Lovley, Derek R.; Yao, Jun (April 20, 2020). "Bioinspired bio-voltage memristors". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 1861. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.1861F. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15759-y. PMC 7171104. PMID 32313096.

- ^ Bolakhe, Saugat. "Lego Robot with an Organic 'Brain' Learns to Navigate a Maze". Scientific American. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Krauhausen, Imke; Koutsouras, Dimitrios A.; Melianas, Armantas; Keene, Scott T.; Lieberth, Katharina; Ledanseur, Hadrien; Sheelamanthula, Rajendar; Giovannitti, Alexander; Torricelli, Fabrizio; Mcculloch, Iain; Blom, Paul W. M.; Salleo, Alberto; Burgt, Yoeri van de; Gkoupidenis, Paschalis (December 2021). "Organic neuromorphic electronics for sensorimotor integration and learning in robotics". Science Advances. 7 (50) eabl5068. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.5068K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abl5068. hdl:10754/673986. PMC 8664264. PMID 34890232. S2CID 245046482.

- ^ Sarkar, Tanmoy; Lieberth, Katharina; Pavlou, Aristea; Frank, Thomas; Mailaender, Volker; McCulloch, Iain; Blom, Paul W. M.; Torriccelli, Fabrizio; Gkoupidenis, Paschalis (7 November 2022). "An organic artificial spiking neuron for in situ neuromorphic sensing and biointerfacing". Nature Electronics. 5 (11): 774–783. doi:10.1038/s41928-022-00859-y. hdl:10754/686016. ISSN 2520-1131. S2CID 253413801.

- ^ "Artificial neurons emulate biological counterparts to enable synergetic operation". Nature Electronics. 5 (11): 721–722. 10 November 2022. doi:10.1038/s41928-022-00862-3. ISSN 2520-1131. S2CID 253469402.

- ^ a b c Grote M (September 2011). "Jeewanu, or the 'particles of life'. The approach of Krishna Bahadur in 20th century origin of life research". Journal of Biosciences. 36 (4): 563–570. doi:10.1007/s12038-011-9087-0. PMID 21857103. S2CID 19551399.

- ^ Caren LD, Ponnamperuma C (1967). A review of some experiments on the synthesis of 'Jeewanu'. NASA Technical Memorandum X-1439. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.9322. OCLC 761398715.

- ^ "Engineers Made Themselves Some Cyborg Cells". Popular Mechanics. 2023-01-11. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "'Cyborg' bacteria deliver green fuel source from sunlight". BBC News. 2017-08-22. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Peplow, Mark (2005-10-17). "Cyborg cells sense humidity". Nature. doi:10.1038/news051017-3. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Berry, Vikas; Saraf, Ravi F. (2005-10-21). "Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles on Live Bacterium: An Avenue to Fabricate Electronic Devices". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (41): 6668–6673. Bibcode:2005ACIE...44.6668B. doi:10.1002/anie.200501711. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 16215974. S2CID 15662656.

- ^ "Cyborg bacteria outperform plants when turning sunlight into useful compounds (video)". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Sakimoto, Kelsey K.; Wong, Andrew Barnabas; Yang, Peidong (2016-01-01). "Self-photosensitization of nonphotosynthetic bacteria for solar-to-chemical production". Science. 351 (6268): 74–77. Bibcode:2016Sci...351...74S. doi:10.1126/science.aad3317. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26721997. S2CID 206642914.

- ^ Kornienko, Nikolay; Sakimoto, Kelsey K.; Herlihy, David M.; Nguyen, Son C.; Alivisatos, A. Paul; Harris, Charles. B.; Schwartzberg, Adam; Yang, Peidong (2016-10-18). "Spectroscopic elucidation of energy transfer in hybrid inorganic–biological organisms for solar-to-chemical production". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (42): 11750–11755. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11311750K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1610554113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5081607. PMID 27698140.

- ^ Contreras-Llano, Luis E.; Liu, Yu-Han; Henson, Tanner; Meyer, Conary C.; Baghdasaryan, Ofelya; Khan, Shahid; Lin, Chi-Long; Wang, Aijun; Hu, Che-Ming J.; Tan, Cheemeng (2023-01-11). "Engineering Cyborg Bacteria Through Intracellular Hydrogelation". Advanced Science. 10 (9) 2204175. Bibcode:2023AdvSc..1004175C. doi:10.1002/advs.202204175. ISSN 2198-3844. PMC 10037956. PMID 36628538. S2CID 255593443.

Artificial cell

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Principles and Definitions

Artificial cells, also termed synthetic cells or protocells, are non-living engineered constructs designed to replicate select functions of natural biological cells, including compartmentalization, metabolic processes, and informational processing, typically through bottom-up molecular assembly or top-down genome minimization.[4] These entities aim to embody minimal requirements for life-like behavior without achieving full autonomy or reproduction in the biological sense, focusing instead on controlled mimicry for scientific inquiry or applications.[10] Unlike natural cells, artificial cells lack inherent evolutionary history and are built to isolate causal mechanisms underlying cellular phenomena, such as self-assembly and responsiveness to environmental cues.[11] Central to artificial cell design are three foundational components: a bounding compartment, often formed by lipid bilayers or synthetic polymers to maintain internal homeostasis; biochemical machinery for processes like transcription, translation, and energy generation; and genetic or informational elements directing these activities, such as DNA or RNA templates.[12] Compartmentalization enables selective permeability and protection of internal reactions, mimicking the plasma membrane's role in natural cells by encapsulating enzymes, nucleotides, or metabolites within vesicles that can sustain gradients and fluxes.[13] Metabolic principles emphasize self-sustained cycles, as demonstrated in constructs integrating ATP production via glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation analogs, ensuring transient functionality without external inputs beyond initial setup.[11] Minimalism governs the core principles, positing that viability requires only indispensable elements—evidenced by top-down approaches yielding cells with as few as 473 genes for self-replication, or bottom-up systems limited to vesicle growth, division, and basic polymer synthesis.[14] This reductionist framework tests hypotheses on life's prerequisites, such as whether bounded chemistry alone suffices for emergent properties like adaptation or quorum sensing, though current prototypes fall short of indefinite autonomy due to inefficiencies in coupled processes.[2] Principles of causality prioritize dissecting interdependent modules, revealing that membrane fluidity and informational fidelity directly influence functional persistence, as perturbations in one disrupt overall protocell integrity.[4]Essential Components of Biological vs. Artificial Cells

Biological cells fundamentally consist of a semi-permeable plasma membrane formed by a phospholipid bilayer embedded with approximately 1,050 proteins in model organisms like E. coli, which regulates transport, signaling, and compartmentalization.[1] Enclosed within is genetic material, such as DNA comprising 4.6 million base pairs and 4,288 genes in E. coli, directing protein synthesis via ribosomes and translation machinery. Metabolic systems, including enzymatic pathways for energy production like ATP synthesis through proton gradients, sustain growth, replication, and adaptability.[1] Artificial cells, constructed via bottom-up approaches, replicate these elements minimally to mimic cellular functions. They typically feature synthetic compartments like liposomes or polymersomes made from 1-2 phospholipid types, often incorporating a single pore-forming protein such as α-hemolysin for selective permeability, but with far lower protein density than natural membranes.[1] Genetic components, when present, involve minimal DNA constructs (e.g., 1.77 kilobase pairs encoding 2 genes) or cell-free transcription-translation (IVTT) systems for protein expression, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) production inside vesicles.[4] Metabolic machinery is simplified, with encapsulated enzymes or reconstituted ATPases driven by external gradients, lacking the self-sustaining complexity of biological metabolism.[15] Key differences arise in integration and autonomy: biological cells exhibit coupled processes for growth via de novo lipid synthesis and division through cytoskeletal proteins, whereas artificial cells achieve rudimentary growth through fatty acid insertion and division via osmotic pressure or crowding, without heritability or full energy regeneration. Artificial designs prioritize targeted functions like gene cascades or signal processing over comprehensive replication.[15][4]| Component | Biological Cells | Artificial Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane | Phospholipid bilayer with ~1,050 proteins | Liposomes/polymersomes with 1-2 lipids, limited pores |

| Genetic Material | DNA (millions bp, thousands genes) | Minimal DNA/RNA (kb scale, few genes) or none |

| Protein Synthesis | Integrated ribosomes/translation | Encapsulated IVTT systems |

| Energy/Metabolism | Full enzymatic pathways, ATP via respiration | Reconstituted enzymes/ATPases, external dependencies |

| Growth/Division | De novo synthesis, protein-mediated | Lipid insertion, osmotic/mechanical |

Historical Development

Early Conceptual Foundations (Pre-1960s)

In the early 20th century, French physiologist Stéphane Leduc advanced concepts of synthetic biology through experiments demonstrating that inorganic salts and simple solutions could produce structures mimicking biological growth and organization via osmotic and diffusive processes.[16] In his 1911 book The Mechanism of Life, Leduc described forming artificial "organisms" resembling plant tissues, fungal mycelia, and even hydra-like forms by diffusing copper sulfate into sodium silicate or ferrocyanide solutions, resulting in rhythmic oscillations, branching patterns, and apparent morphogenesis without vital forces.[17] These phenomena, driven by physicochemical gradients rather than enzymatic activity, led Leduc to argue that life emerges from physical laws governing colloids and solutions, challenging vitalism and laying groundwork for bottom-up chemical assembly of cell-like entities.[16] However, Leduc later clarified that his constructs were not true life but models illustrating life's mechanistic basis, as they lacked heredity or sustained metabolism.[18] Building on colloidal chemistry, Soviet biochemist Aleksandr Oparin proposed in 1924 that life's origins involved spontaneous aggregation of organic colloids into membrane-bound droplets, prefiguring artificial cell compartments.[19] Oparin's heterotrophic theory posited coacervates—dense liquid phases formed by liquid-liquid phase separation of macromolecules like proteins and polysaccharides—as primitive protocells capable of concentrating metabolites and evolving toward cellular complexity under prebiotic conditions.[20] Independently, British scientist J.B.S. Haldane echoed this in 1929, envisioning "hot dilute soup" of organics yielding colloidal aggregates that could adsorb enzymes and form replicating units, though emphasizing photochemical synthesis over purely abiotic assembly.[21] Experimental validation came in the 1930s when Dutch chemist Hugo Bungenberg de Jong identified coacervation in gelatin-gum arabic systems, producing stable, selective droplets that exhibited growth by coalescence and rudimentary division-like fission.[19] These models, while not engineered for function, provided causal frameworks for artificial cells as bounded chemical reactors, prioritizing empirical phase behavior over speculative vitalism. By the mid-1950s, biomedical applications emerged with Canadian researcher Thomas Ming Swi Chang's conceptualization of artificial cells as semipermeable microcapsules for enzyme immobilization and toxin removal.[4] In 1957, Chang described polymer-based enclosures mimicking red blood cells, encapsulating urease to hydrolyze urea in dialysis-like setups, achieving 90% efficiency in vitro without immune rejection.[4] This shifted focus from origin-of-life models to utilitarian mimics, using nylon or collodion membranes permeable to substrates but not proteins, demonstrating feasibility for extracorporeal therapies.[22] Pre-1960s foundations thus emphasized physicochemical self-organization—via osmosis, phase separation, and encapsulation—over genetic engineering, establishing that cell-like boundaries and reactivity could arise from simple matter under controlled gradients, though lacking true autonomy or replication.[20]Pioneering Experiments (1960s-1990s)

In 1957, Thomas Ming Swi Chang developed the first artificial cells using an emulsion phase separation method to create ultrathin polymeric membrane microcapsules containing hemoglobin and red blood cell enzymes, laying the foundation for microscopic and nanoscale artificial cells aimed at biomedical applications such as blood substitutes.[23] By 1964, Chang advanced this approach through interfacial coacervation and polymerization techniques, encapsulating enzymes, hemoglobin, and even intact cells within polymer or crosslinked protein membranes, demonstrating semipermeable properties that allowed substrate diffusion while retaining contents.[23] These constructs, approximately cell-sized at 1-100 micrometers, represented early efforts to mimic cellular compartmentalization for therapeutic replacement of organ functions.[23] In 1965, Alec D. Bangham and colleagues discovered liposomes by dispersing dry phospholipids in an aqueous medium with negative stain, observing under electron microscopy the spontaneous formation of self-enclosed, multilamellar lipid vesicles that served as models for biological membranes.[24] These structures, with diameters ranging from 20 nanometers to several micrometers, exhibited bilayer organization and permeability properties akin to cell membranes, enabling studies of ion transport, drug interactions, and membrane stability without relying on living cells.[25] Liposomes provided a bottom-up platform for artificial cells, influencing subsequent encapsulation techniques for enzymes and drugs, though initial multilamellar forms limited uniformity until refinements in the 1970s produced unilamellar variants via sonication or extrusion.[24] Sidney W. Fox's experiments in the late 1950s and 1960s produced proteinoid microspheres by thermally copolymerizing dry amino acids at 150-180°C to form random polypeptides (proteinoids), which, upon hydration, self-assembled into spherical protocell-like structures measuring 1-5 micrometers with peptide bonds, catalytic activity, and budding behaviors suggestive of primitive cellular division.[26] These microspheres demonstrated osmotically induced growth, selective permeability, and weak enzymatic functions, supporting Fox's hypothesis of thermal origins for early life forms, though critics noted the harsh synthesis conditions diverged from plausible prebiotic environments. By the 1970s, Fox extended this to multilayered assemblies incorporating lipids and nucleic acids, aiming to replicate coupled metabolic and replicative processes in artificial protocells.[27] During the 1970s and 1980s, researchers built on these foundations with hybrid systems, such as enzyme-loaded liposomes for sustained catalysis and microencapsulated prokaryotic cells for immunoprotected delivery, bridging artificial and biological components in applications like uremia treatment.[23] Into the 1990s, advancements included pH-sensitive liposomes and polymersomes for controlled release, enhancing artificial cell viability, though challenges in stability and complexity persisted, setting the stage for genomic integrations in later decades.[28] These experiments collectively established core principles of compartmentalization, membrane mimicry, and functional encapsulation, despite limitations in achieving full autonomy or heredity.[23]Modern Milestones (2000s-2020s)

In 2004, researchers demonstrated sustained gene expression within artificial lipid vesicles, encapsulating an Escherichia coli cell-free transcription-translation system in phospholipid liposomes to produce green fluorescent protein over several hours, establishing a foundational bioreactor model for bottom-up synthetic cells.[29] This approach highlighted the potential for compartmentalized, non-living systems to mimic cellular protein synthesis without relying on intact biological hosts. Parallel efforts focused on protocell membrane dynamics, with Jack Szostak's group reporting in 2009 a mechanism for coupled growth and division in fatty acid-based vesicles: multilamellar vesicles absorbed free fatty acids to expand surface area, followed by division under gentle agitation, while retaining encapsulated RNA or other contents to simulate primitive replication cycles.[30] These experiments underscored the biophysical feasibility of self-reproducing compartments under prebiotic-like conditions, driven by amphiphile self-assembly rather than enzymatic machinery. A pivotal top-down milestone occurred in 2010 when the J. Craig Venter Institute synthesized and assembled the 1.08-megabase genome of Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 from oligonucleotides, then transplanted it into enucleated M. capricolum recipient cells, yielding viable, self-replicating bacteria controlled solely by the synthetic genome and exhibiting donor-like traits such as specific colony morphology.[31] This proof-of-principle validated de novo genome design and transplantation, though the process retained existing cellular hardware from the host. By 2016, refinements produced JCVI-syn3.0, a minimal synthetic bacterium with a 531-kilobase genome containing only 473 genes—fewer than any naturally occurring free-living organism—achieved through iterative design, synthesis, and testing to identify essential functions for robust growth and division in nutrient-rich media.[32] The genome included 149 genes of unknown function, revealing gaps in understanding life's core requirements. In the 2020s, bottom-up systems advanced toward autonomy, as in 2020 experiments where liposomes encapsulating cell-free expression machinery produced β-barrel porins and lipid-synthesizing enzymes, enabling partial self-modification of the enclosing membrane via endogenous phospholipid generation.[33] Further, JCVI-syn3.0 derivatives underwent adaptive laboratory evolution by 2023, rapidly acquiring mutations for improved fitness in nutrient-limited conditions, demonstrating evolvability in genomically constrained synthetic cells despite a 45% reduction from natural bacterial genomes.[34] These developments collectively bridged empirical construction with functional realism, though full autonomy remains constrained by incomplete replication of interdependent cellular processes.Construction Approaches

Bottom-Up Engineering

Bottom-up engineering constructs artificial cells through the de novo assembly of molecular components, such as lipids, nucleic acids, proteins, and peptides, into compartmentalized structures that mimic biological functions like boundary formation, internal reactions, and response to stimuli. This approach emphasizes hierarchical self-organization from purified or synthesized building blocks, allowing precise control over composition absent in top-down methods derived from living cells. Advances since the early 2000s have leveraged synthetic chemistry and biochemistry to create protocells capable of rudimentary metabolism and replication, driven by empirical demonstrations of molecular interactions under defined conditions.[35][36][37] Core techniques include the self-assembly of amphiphilic molecules into lipid bilayers or alternative membranes, such as polymersomes, via hydrophobic effects and electrostatic interactions, followed by encapsulation of functional cargoes like enzymes or genetic polymers. Microfluidics and templated assembly, including DNA origami scaffolds, enable scalable production and programmed architectures, with encapsulation efficiencies improved through sequential injection methods reported in studies from 2010 onward. These methods have yielded vesicles sustaining enzymatic cascades, as in 1994 demonstrations of poly(adenylic acid) synthesis inside liposomes, with refinements in the 2020s incorporating orthogonal biopolymers for stability.[38][35][38] Key prototypes demonstrate functional mimicry, such as lipid-based synthetic cells achieving complete fission via Dynamin A ring contraction on cholesterol-linked DNA nanostructures, enabling division cycles analogous to bacterial processes. In 2022, de novo assembly of DNA cytoskeletons within vesicles provided programmable motility and shape control, integrating actin-like polymerization for cargo transport. By 2024, efforts like those of Cees Dekker's group produced fully synthetic cells undergoing mechanochemical division, highlighting causal links between cytoskeletal forces and membrane deformation derived from biophysical measurements. These developments underscore bottom-up engineering's potential for dissecting minimal life requirements, though challenges persist in coupling replication with sustained metabolism.[35][39][40]

Molecular Assembly Techniques

Molecular assembly techniques in bottom-up artificial cell construction rely on self-organization principles to form compartmentalized structures from lipids, polymers, DNA, and other biomolecules, enabling controlled encapsulation of functional components like enzymes and genetic material. Lipid-based vesicles, such as liposomes and giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), represent a foundational method, formed through thin-film hydration, electroformation, or microfluidics-driven emulsification, which spontaneously create bilayer membranes encapsulating aqueous contents. These techniques achieve vesicle sizes from 100 nm to 100 μm, with GUVs particularly suited for mimicking eukaryotic cell dimensions and supporting dynamic processes like fusion and division.[6][41] DNA nanotechnology facilitates precise structural control via self-assembling DNA origami tiles or nanostructures that act as scaffolds, cytoskeletons, or pores within lipid membranes. For example, DNA amphiphiles integrate into bilayers through hydrophobic tails, enabling programmable assembly and stabilization of protocell interiors via electrostatic interactions with cationic lipids, as demonstrated in 2017 experiments forming DNA networks under membranes without enzymatic ligation. Peptide-DNA hybrids further enhance cytoskeletal mimicry by enabling actin-like self-organization for cargo transport and shape maintenance in synthetic compartments.[42][43][44] Polymer assemblies, including polymersomes from amphiphilic block copolymers and coacervate droplets via liquid-liquid phase separation, offer robust alternatives to lipids with greater mechanical stability and permeability tuning. Polymersomes self-assemble in aqueous solutions through hydrophobic collapse, encapsulating proteins or DNA with efficiencies up to 50% volume fraction, while coacervates form membraneless organelles that concentrate macromolecules for reaction acceleration. Hybrid lipid-polymer systems combine biocompatibility with durability, assembled via coextrusion or layer-by-layer deposition. Microfluidic platforms integrate these methods for scalable production, generating uniform vesicles at rates exceeding 10^3 per second by droplet templating and solvent evaporation.[45][6][46]