Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Earliest known life forms

View on Wikipedia

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

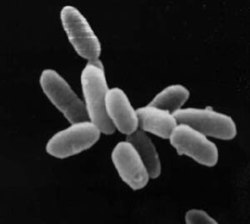

The earliest known life forms on Earth may be as old as 4.1 billion years (or Ga) according to biologically fractionated graphite inside a single zircon grain in the Jack Hills range of Australia.[2] The earliest evidence of life found in a stratigraphic unit, not just a single mineral grain, is the 3.7 Ga metasedimentary rocks containing graphite from the Isua Supracrustal Belt in Greenland.[3] The earliest direct known life on Earth are stromatolite fossils which have been found in 3.480-billion-year-old geyserite uncovered in the Dresser Formation of the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia.[4] Various microfossils of microorganisms have been found in 3.4 Ga rocks, including 3.465-billion-year-old Apex chert rocks from the same Australian craton region,[5] and in 3.42 Ga hydrothermal vent precipitates from Barberton, South Africa.[1] Much later in the geologic record, likely starting in 1.73 Ga, preserved molecular compounds of biologic origin are indicative of aerobic life.[6] Therefore, the earliest time for the origin of life on Earth is at least 3.5 billion years ago and possibly as early as 4.1 billion years ago — not long after the oceans formed 4.5 billion years ago and after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago.[7]

Biospheres

[edit]Earth is the only place in the universe known to harbor life, where it exists in myriad environments.[8][9] The origin of life on Earth was at least 3.5 billion years ago, possibly as early as 3.8–4.1 billion years ago.[2][3][4] Since its emergence, life has persisted in several geological environments. The Earth's biosphere extends down to at least 10 km (6.2 mi) below the seafloor,[10][11] up to 41–77 km (25–48 mi)[12][13] into the atmosphere,[14][15][16] and includes soil, hydrothermal vents, and rock.[17][18] Further, the biosphere has been found to extend at least 914.4 m (3,000 ft; 0.5682 mi) below the ice of Antarctica[19][20] and includes the deepest parts of the ocean.[21][22][23][24] In July 2020, marine biologists reported that aerobic microorganisms (mainly) in "quasi-suspended animation" were found in organically poor sediment 76.2 m (250 ft) below the seafloor in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG) ("the deadest spot in the ocean").[25] Microbes have been found in the Atacama Desert in Chile, one of the driest places on Earth,[26] and in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments which can reach temperatures over 400 °C.[27] Microbial communities can also survive in cold permafrost conditions down to -25 °C.[28] Under certain test conditions, life forms have been observed to survive in the vacuum of outer space.[29][30] More recently, studies conducted on the International Space Station found that bacteria could survive in outer space.[31] In February 2023, findings of a "dark microbiome" of microbial dark matter of unfamiliar microorganisms in the Atacama Desert in Chile, a Mars-like region of planet Earth, were reported.[32]

Geochemical evidence

[edit]The age of Earth is about 4.54 billion years;[7][33][34] the earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago according to the stromatolite record.[35] Some computer models suggest life began as early as 4.5 billion years ago.[36][37] The oldest evidence of life is indirect in the form of isotopic fractionation processes. Microorganisms will preferentially use the lighter isotope of an atom to build biomass, as it takes less energy to break the bonds for metabolic processes.[38] Biologic material will often have a composition that is enriched in lighter isotopes compared to the surrounding rock it's found in. Carbon isotopes, expressed scientifically in parts per thousand difference from a standard as δ13C, are frequently used to detect carbon fixation by organisms and assess if purported early life evidence has biological origins. Typically, life will preferentially metabolize the isotopically light 12C isotope instead of the heavier 13C isotope. Biologic material can record this fractionation of carbon.

The oldest disputed geochemical evidence of life is isotopically light graphite inside a single zircon grain from the Jack Hills in Western Australia.[2][39] The graphite showed a δ13C signature consistent with biogenic carbon on Earth. Other early evidence of life is found in rocks both from the Akilia Sequence[40] and the Isua Supracrustal Belt (ISB) in Greenland.[3][41] These 3.7 Ga metasedimentary rocks also contain graphite or graphite inclusions with carbon isotope signatures that suggest biological fractionation.

The primary issue with isotopic evidence of life is that abiotic processes can fractionate isotopes and produce similar signatures to biotic processes.[42] Reassessment of the Akilia graphite show that metamorphism, Fischer-Tropsch mechanisms in hydrothermal environments, and volcanic processes may be responsible for enrichment lighter carbon isotopes.[43][44][45] The ISB rocks that contain the graphite may have experienced a change in composition from hot fluids, i.e. metasomatism, thus the graphite may have been formed by abiotic chemical reactions.[42] However, the ISB's graphite is generally more accepted as biologic in origin after further spectral analysis.[3][41]

Metasedimentary rocks from the 3.5 Ga Dresser Formation, which experienced less metamorphism than the sequences in Greenland, contain better preserved geochemical evidence.[46] Carbon isotopes as well as sulfur isotopes found in barite, which are fractionated by microbial metabolisms during sulfate reduction,[47] are consistent with biological processes.[48][49] However, the Dresser formation was deposited in an active volcanic and hydrothermal environment,[46] and abiotic processes could still be responsible for these fractionations.[50] Many of these findings are supplemented by direct evidence, typically by the presence of microfossils, however.

Fossil evidence

[edit]Fossils are direct evidence of life. In the search for the earliest life, fossils are often supplemented by geochemical evidence. The fossil record does not extend as far back as the geochemical record due to metamorphic processes that erase fossils from geologic units.

Stromatolites

[edit]Stromatolites are laminated sedimentary structures created by photosynthetic organisms as they establish a microbial mat on a sediment surface. An important distinction for biogenicity is their convex-up structures and wavy laminations, which are typical of microbial communities who build preferentially toward the sun.[51] A disputed report of stromatolites is from the 3.7 Ga Isua metasediments that show convex-up, conical, and domical morphologies.[52][53][54] Further mineralogical analysis disagrees with the initial findings of internal convex-up laminae, a critical criterion for stromatolite identification, suggesting that the structures may be deformation features (i.e. boudins) caused by extensional tectonics in the Isua Supracrustal Belt.[55][56]

The earliest direct evidence of life are stromatolites found in 3.48 billion-year-old chert in the Dresser formation of the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia.[4] Several features in these fossils are difficult to explain with abiotic processes, for example, the thickening of laminae over flexure crests that is expected from more sunlight.[57] Sulfur isotopes from barite veins in the stromatolites also favor a biologic origin.[58] However, while most scientists accept their biogenicity, abiotic explanations for these fossils cannot be fully discarded due to their hydrothermal depositional environment and debated geochemical evidence.[50]

Most archean stromatolites older than 3.0 Ga are found in Australia or South Africa. Stratiform stromatolites from the Pilbara Craton have been identified in the 3.47 Ga Mount Ada Basalt.[59] Barberton, South Africa hosts stratiform stromatolites in the 3.46 Hooggenoeg, 3.42 Kromberg and 3.33 Ga Mendon Formations of the Onverwacht Group.[60][61] The 3.43 Ga Strelley Pool Formation in Western Australia hosts stromatolites that demonstrate vertical and horizontal changes that may demonstrate microbial communities responding to transient environmental conditions.[62] Thus, it is likely anoxygenic or oxygenic photosynthesis has been occurring since at least 3.43 Ga Strelley Pool Formation.[63]

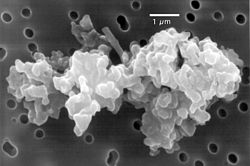

Microfossils

[edit]Claims of the earliest life using fossilized microorganisms (microfossils) are from hydrothermal vent precipitates from an ancient sea-bed in the Nuvvuagittuq Belt of Quebec, Canada. These may be as old as 4.28 billion years, which would make it the oldest evidence of life on Earth, suggesting "an almost instantaneous emergence of life" after ocean formation 4.41 billion years ago.[64][65] These findings may be better explained by abiotic processes: for example, silica-rich waters,[66] "chemical gardens,"[67] circulating hydrothermal fluids,[68] and volcanic ejecta[69] can produce morphologies similar to those presented in Nuvvuagittuq.

The 3.48 Ga Dresser formation hosts microfossils of prokaryotic filaments in silica veins, the earliest fossil evidence of life on Earth,[70] but their origins may be volcanic.[71] 3.465-billion-year-old Australian Apex chert rocks may once have contained microorganisms,[72][5] although the validity of these findings has been contested.[73][74] "Putative filamentous microfossils," possibly of methanogens and/or methanotrophs that lived about 3.42-billion-year-old in "a paleo-subseafloor hydrothermal vein system of the Barberton greenstone belt, have been identified in South Africa."[1] A diverse set of microfossil morphologies have been found in the 3.43 Ga Strelley Pool Formation including spheroid, lenticular, and film-like microstructures.[75] Their biogenicity are strengthened by their observed chemical preservation.[76] The early lithification of these structures allowed important chemical tracers, such as the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, to be retained at levels higher than is typical in older, metamorphosed rock units.

Molecular biomarkers

[edit]Biomarkers are compounds of biologic origin found in the geologic record that can be linked to past life.[77] Although they aren't preserved until the late Archean, they are important indicators of early photosynthetic life. Lipids are particularly useful biomarkers because they can survive for long periods of geologic time and reconstruct past environments.[78]

Fossilized lipids were reported from 2.7 Ga laminated shales from the Pilbara Craton[79] and the 2.67 Ga Kaapvaal craton in South Africa.[80] However, the age of these biomarkers and whether their deposition was synchronous with their host rocks were debated,[81] and further work showed that the lipids were contaminants.[82] The oldest "clearly indigenous"[83] biomarkers are from the 1.64 Ga Barney Creek Formation in the McArthur Basin in Northern Australia,[84][85] but hydrocarbons from the 1.73 Ga Wollogorang Formation in the same basin have also been detected.[83]

Other indigenous biomarkers can be dated to the Mesoproterozoic era (1.6–1.0 Ga). The 1.4 Ga Hongshuizhuang Formation in the North China Craton contains hydrocarbons in shales that were likely sourced from prokaryotes.[86] Biomarkers were found in siltstones from the 1.38 Ga Roper Group of the McArthur Basin.[87] Hydrocarbons possibly derived from bacteria and algae were reported in 1.37 Ga Xiamaling Formation of the NCC.[88] The 1.1 Ga Atar/El Mreïti Group in the Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania show indigenous biomarkers in black shales.[89]

Genomic evidence

[edit]By comparing the genomes of modern organisms (in the domains Bacteria and Archaea), it is evident that there was a last universal common ancestor (LUCA). Another term for the LUCA is the cenancestor and can be viewed as a population of organisms rather than a single entity.[90] LUCA is not thought to be the first life on Earth, but rather the only type of organism of its time to still have living descendants. In 2016, M. C. Weiss and colleagues proposed a minimal set of genes that each occurred in at least two groups of Bacteria and two groups of Archaea. They argued that such a distribution of genes would be unlikely to arise by horizontal gene transfer, and so any such genes must have derived from the LUCA.[91] A molecular clock model suggests that the LUCA may have lived 4.477–4.519 billion years ago, within the Hadean eon.[36][37]

RNA replicators

[edit]Model Hadean-like geothermal microenvironments were demonstrated to have the potential to support the synthesis and replication of RNA and thus possibly the evolution of primitive life.[92] Porous rock systems, comprising heated air-water interfaces, were shown to facilitate ribozyme catalyzed RNA replication of sense and antisense strands and then subsequent strand-dissociation.[92] This enabled combined synthesis, release and folding of active ribozymes.[92]

Hypotheses for the origin of life on Earth

[edit]Extraterrestrial origin for early life

[edit]

While current geochemical evidence dates the origin of life to possibly as early as 4.1 Ga, and fossil evidence shows life at 3.5 Ga, some researchers speculate that life may have started nearly 4.5 billion years ago.[36][37] According to biologist Stephen Blair Hedges, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth ... then it could be common in the universe."[95][96][97] The possibility that terrestrial life forms may have been seeded from outer space has been considered.[98][99] In January 2018, a study found that 4.5 billion-year-old meteorites found on Earth contained liquid water along with prebiotic complex organic substances that may be ingredients for life.[94]

Hydrothermal vents

[edit]Hydrothermal vents have long been hypothesized to be the grounds from which life originated. The properties of ancient hydrothermal vents, such as the geochemistry, pressure, and temperatures, have the potential to create organic molecules from inorganic molecules.[100] In experiments performed by NASA, it was shown that the organic compounds formate and methane could be created from inorganics in the conditions of ancient hydrothermal vents.[101] The production of organic molecules could have led to the formation of more complex organic molecules, such as amino acids that can eventually form RNA or DNA.

Darwin's hypothesis

[edit]Charles Darwin is well-known for his theory of evolution via natural selection. His theory for the origin of life was a "warm little pond" that harbored necessary elements for the creation of life such as "ammonia and phosphoric salts, lights, heat, electricity … so that a protein compound was chemically formed ready to undergo still more complex changes."[102] However, he mentioned that such an environment today would likely have been destroyed faster than it would take to form life. With this, Darwin's ideas are generally regarded as the spontaneous generation hypothesis.[citation needed]

Oparin–Haldane hypothesis

[edit]In 1924, Alexander Oparin suggested that the early atmosphere on Earth was full of reducing components such as ammonia, methane, water vapor, and hydrogen gas.[102] This was proposed after atmospheric methane was discovered on other planets. Later, in 1929, J. B. S. Haldane published an article that proposed the same conditions for early life on Earth as Oparin suggested. Their hypothesis was later supported by the Miller–Urey experiment.

Miller–Urey experiment

[edit]

At the University of Chicago in 1953, a graduate student named Stanley Miller carried out an experiment under his professor, Harold Urey.[103] The method would allow for reducing gases to simulate the atmosphere early on Earth and a spark to simulate lightning. There was a reflux apparatus that would heat water and mix into the atmosphere where it would then cool and run into the "primordial ocean". The gases that were used to mimic the reducing atmosphere were methane, ammonia, water vapor, and hydrogen gas. Within a day of allowing the apparatus to run, the experiment yielded a "brown sludge" which was later tested and found to include the following amino acids: glycine, alanine, aspartic acid, and aminobutyric acid. In the following years, many scientists attempted to replicate the results of the experiment and is now known as a fundamental approach to the study of abiogenesis. The Miller–Urey experiment was able to simulate the early conditions of Earth's atmosphere and produced essential amino acids that likely contributed to the production of life.[103]

Clay hypothesis

[edit]Cairns-Smith first introduced this hypothesis in 1966, where they proposed that any crystallization process is likely to involve a basic biological evolution.[104] Hartman then added on to this hypothesis by proposing in 1975 that metabolism could have developed from a simple environment such as clays. Clays have the ability to synthesize monomers such as amino acids, nucleotides, and other building blocks and polymerize them to create macromolecules. This makes it possible for nucleic acids like RNA or DNA to be created from clay, and cells could further evolve from there.

Gallery

[edit]Earliest known life forms

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cavalazzi, Barbara; et al. (14 July 2021). "Cellular remains in a ~3.42-billion-year-old subseafloor hydrothermal environment". Science Advances. 7 (9) eabf3963. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.3963C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf3963. PMC 8279515. PMID 34261651.

- ^ a b c Bell, Elizabeth; Boehnke, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; Mao, Wendy L. (24 November 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (47): 14518–21. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. PMC 4664351. PMID 26483481.

- ^ a b c d Ohtomo, Yoko; Kakegawa, Takeshi; Ishida, Akizumi; et al. (January 2014). "Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks". Nature Geoscience. 7 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7...25O. doi:10.1038/ngeo2025. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 54767854.

- ^ a b c Noffke, Nora; Christian, Daniel; Wacey, David; Hazen, Robert M. (16 November 2013). "Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. 13 (12): 1103–24. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13.1103N. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3870916. PMID 24205812.

- ^ a b Schopf, J. William; Kitajima, Kouki; Spicuzza, Michael J.; Kudryavtsev, Anatolly B.; Valley, John W. (2017). "SIMS analyses of the oldest known assemblage of microfossils document their taxon-correlated carbon isotope compositions". PNAS. 115 (1): 53–58. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115...53S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1718063115. PMC 5776830. PMID 29255053.

- ^ Hallmann, Christian; French, Katherine L.; Brocks, Jochen J. (2022-04-01). "Biomarkers in the Precambrian: Earth's Ancient Sedimentary Record of Life". Elements. 18 (2): 93–99. Bibcode:2022Eleme..18...93H. doi:10.2138/gselements.18.2.93. ISSN 1811-5217. S2CID 253517035.

- ^ a b "Age of the Earth". United States Geological Survey. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 2006-01-10.

- ^ Graham, Robert W. (February 1990). "Extraterrestrial Life in the Universe" (PDF). NASA (NASA Technical Memorandum 102363). 90. Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio: 22464. Bibcode:1990STIN...9022464G. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Altermann, Wladyslaw (2009). "From Fossils to Astrobiology — A Roadmap to Fata Morgana?". In Seckbach, Joseph; Walsh, Maud (eds.). From Fossils to Astrobiology: Records of Life on Earth and the Search for Extraterrestrial Biosignatures. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology. Vol. 12. Springer. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-4020-8836-0. LCCN 2008933212.

- ^ Klein, JoAnna (19 December 2018). "Deep Beneath Your Feet, They Live in the Octillions — The real journey to the center of the Earth has begun, and scientists are discovering subsurface microbial beings that shake up what we think we know about life". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Plümper, Oliver; King, Helen E.; Geisler, Thorsten; Liu, Yang; Pabst, Sonja; Savov, Ivan P.; Rost, Detlef; Zack, Thomas (2017-04-25). "Subduction zone forearc serpentinites as incubators for deep microbial life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (17): 4324–9. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.4324P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1612147114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5410786. PMID 28396389.

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (4 November 2019). "Did Life from Earth Escape the Solar System Eons Ago?". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Smith, David J. (October 2013). "Microbes in the Upper Atmosphere and Unique Opportunities for Astrobiology Research". Astrobiology. 13 (10): 981–990. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..981S. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1074. ISSN 1531-1074. PMID 24106911.

- ^ University of Georgia (25 August 1998). "First-Ever Scientific Estimate Of Total Bacteria On Earth Shows Far Greater Numbers Than Ever Known Before". Science Daily. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Hadhazy, Adam (12 January 2015). "Life Might Thrive a Dozen Miles Beneath Earth's Surface". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 2020-11-02.

- ^ Fox-Skelly, Jasmin (24 November 2015). "The Strange Beasts That Live In Solid Rock Deep Underground". BBC online. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Suzuki, Yohey; et al. (2 April 2020). "Deep microbial proliferation at the basalt interface in 33.5–104 million-year-old oceanic crust". Communications Biology. 3 (136): 136. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-0860-1. PMC 7118141. PMID 32242062.

- ^ University of Tokyo (2 April 2020). "Discovery of life in solid rock deep beneath sea may inspire new search for life on Mars — Bacteria live in tiny clay-filled cracks in solid rock millions of years old". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Griffiths, Huw J.; et al. (15 February 2021). "Breaking All the Rules: The First Recorded Hard Substrate Sessile Benthic Community Far Beneath an Antarctic Ice Shelf". Frontiers in Marine Science. 8. Bibcode:2021FrMaS...842040G. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.642040.

- ^ Fox, Douglas (20 August 2014). "Lakes under the ice: Antarctica's secret garden". Nature. 512 (7514): 244–6. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..244F. doi:10.1038/512244a. PMID 25143097.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (17 March 2013). "Microbes Thrive in Deepest Spot on Earth". LiveScience. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Glud, Ronnie; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Middelboe, Mathias; Oguri, Kazumasa; Turnewitsch, Robert; Canfield, Donald E.; Kitazato, Hiroshi (17 March 2013). "High rates of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth". Nature Geoscience. 6 (4): 284–8. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..284G. doi:10.1038/ngeo1773.

- ^ Oskin, Becky (14 March 2013). "Intraterrestrials: Life Thrives in Ocean Floor". LiveScience. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (15 December 2014). "Microbes discovered by deepest marine drill analysed". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Morono, Yuki; et al. (28 July 2020). "Aerobic microbial life persists in oxic marine sediment as old as 101.5 million years". Nature Communications. 11 (3626): 3626. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3626M. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17330-1. PMC 7387439. PMID 32724059.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (2018-02-26). "Microbes found in one of Earth's most hostile places, giving hope for life on Mars". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat4341. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Georgieva, Magdalena N.; Little, Crispin T. S.; Maslennikov, Valeriy V.; Glover, Adrian G.; Ayupova, Nuriya R.; Herrington, Richard J. (2021-06-01). "The history of life at hydrothermal vents". Earth-Science Reviews. 217 103602. Bibcode:2021ESRv..21703602G. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103602. ISSN 0012-8252.

- ^ Mykytczuk, Nadia C S; Foote, Simon J; Omelon, Chris R; Southam, Gordon; Greer, Charles W; Whyte, Lyle G (2013-02-07). "Bacterial growth at −15 °C; molecular insights from the permafrost bacterium Planococcus halocryophilus Or1". The ISME Journal. 7 (6): 1211–26. Bibcode:2013ISMEJ...7.1211M. doi:10.1038/ismej.2013.8. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 3660685. PMID 23389107.

- ^ Dose, K.; Bieger-Dose, A.; Dillmann, R.; Gill, M.; Kerz, O.; Klein, A.; Meinert, H.; Nawroth, T.; Risi, S.; Stridde, C. (1995). "ERA-experiment "space biochemistry"". Advances in Space Research. 16 (8): 119–129. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.119D. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R. PMID 11542696.

- ^ Horneck, G.; Eschweiler, U.; Reitz, G.; Wehner, J.; Willimek, R.; Strauch, K. (1995). "Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I". Adv. Space Res. 16 (8): 105–118. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.105H. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N. PMID 11542695.

- ^ Kawaguchi, Yuko; et al. (26 August 2020). "DNA Damage and Survival Time Course of Deinococcal Cell Pellets During 3 Years of Exposure to Outer Space". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 2050. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.02050. PMC 7479814. PMID 32983036. S2CID 221300151.

- ^ Azua-Bustos, Armando; et al. (21 February 2023). "Dark microbiome and extremely low organics in Atacama fossil delta unveil Mars life detection limits". Nature Communications. 14 (808): 808. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14..808A. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36172-1. PMC 9944251. PMID 36810853.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094.

- ^ Manhesa, Gérard; Allègre, Claude J.; Dupréa, Bernard; Hamelin, Bruno (May 1980). "Lead isotope study of basic-ultrabasic layered complexes: Speculations about the age of the earth and primitive mantle characteristics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 47 (3): 370–382. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..47..370M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- Lepot, K. (October 2020). "Signatures of early microbial life from the Archean (4 to 2.5 Ga) eon". Earth-Science Reviews. 209 103296. Bibcode:2020ESRv..20903296L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103296. hdl:20.500.12210/62415.

- Baugartner, R.J.; et al. (25 September 2019). "Nano−porous pyrite and organic matter in 3.5-billion-year-old stromatolites record primordial life". Geology. 47 (11): 1039–43. Bibcode:2019Geo....47.1039B. doi:10.1130/G46365.1. S2CID 204258554. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (5 October 2007). "Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils". Precambrian Research. 158 (3–4): 141–155. Bibcode:2007PreR..158..141S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009. ISSN 0301-9268.

- Schopf, J. William (29 June 2006). "Fossil evidence of Archaean life". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 361 (1470): 869–885. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- Allwood, A.C.; et al. (8 June 2006). "Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia". Nature. 441 (7094): 714–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..714A. doi:10.1038/nature04764. PMID 16760969. S2CID 4417746. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Raven, Peter H.; Johnson, George B. (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0. LCCN 2001030052. OCLC 45806501.

- ^ a b c Staff (20 August 2018). "A timescale for the origin and evolution of all of life on Earth". Phys.org. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Betts, Holly C.; Putick, Mark N.; Clark, James W.; Williams, Tom A.; Donoghue, Philip C.J.; Pisani, Davide (20 August 2018). "Integrated genomic and fossil evidence illuminates life's early evolution and eukaryote origin". Nature. 2 (10): 1556–62. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2.1556B. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x. PMC 6152910. PMID 30127539.

- ^ Farquhar, G D; Ehleringer, J R; Hubick, K T (June 1989). "Carbon Isotope Discrimination and Photosynthesis". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 40 (1): 503–537. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443. ISSN 1040-2519.

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (2015-10-31). "Tiny zircons suggest life on Earth started earlier than we thought, UCLA researchers say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ Mojzsis, S. J.; Arrhenius, G.; McKeegan, K. D.; Harrison, T. M.; Nutman, A. P.; Friend, C. R. L. (1996-11-07). "Evidence for life on Earth before 3,800 million years ago". Nature. 384 (6604): 55–59. Bibcode:1996Natur.384...55M. doi:10.1038/384055a0. hdl:2060/19980037618. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8900275. S2CID 4342620.

- ^ a b Hassenkam, T.; Rosing, M. T. (2017-11-02). "3.7 billion year old biogenic remains". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 10 (5–6) e1380759. doi:10.1080/19420889.2017.1380759. ISSN 1942-0889. PMC 5731516. PMID 29260796.

- ^ a b van Zuilen, Mark A.; Lepland, Aivo; Arrhenius, Gustaf (2002-08-08). "Reassessing the evidence for the earliest traces of life". Nature. 418 (6898): 627–630. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..627V. doi:10.1038/nature00934. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12167858. S2CID 62804341.

- ^ Papineau, Dominic; De Gregorio, Bradley T.; Stroud, Rhonda M.; Steele, Andrew; Pecoits, Ernesto; Konhauser, Kurt; Wang, Jianhua; Fogel, Marilyn L. (October 2010). "Ancient graphite in the Eoarchean quartz-pyroxene rocks from Akilia in southern West Greenland II: Isotopic and chemical compositions and comparison with Paleoproterozoic banded iron formations". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 74 (20): 5884–5905. Bibcode:2010GeCoA..74.5884P. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2010.07.002. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ MCCOLLOM, T; SEEWALD, J (2006-03-15). "Carbon isotope composition of organic compounds produced by abiotic synthesis under hydrothermal conditions". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 243 (1–2): 74–84. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.243...74M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.01.027. hdl:1912/878. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Lepland, Aivo; van Zuilen, Mark A.; Arrhenius, Gustaf; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Fedo, Christopher M. (2005). "Questioning the evidence for Earth's earliest life—Akilia revisited". Geology. 33 (1): 77. Bibcode:2005Geo....33...77L. doi:10.1130/g20890.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ a b Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Djokic, Tara; Poole, Greg; Tadbiri, Sahand; Steller, Luke; Baumgartner, Raphael (2019), "Depositional Setting of the Fossiliferous, c.3480 Ma Dresser Formation, Pilbara Craton", Earth's Oldest Rocks, Elsevier, pp. 985–1006, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63901-1.00040-x, ISBN 978-0-444-63901-1, S2CID 133958822

- ^ Sim, Min Sub; Woo, Dong Kyun; Kim, Bokyung; Jeong, Hyeonjeong; Joo, Young Ji; Hong, Yeon Woo; Choi, Jy Young (2023-03-15). "What Controls the Sulfur Isotope Fractionation during Dissimilatory Sulfate Reduction?". ACS Environmental Au. 3 (2): 76–86. Bibcode:2023ACSEA...3...76S. doi:10.1021/acsenvironau.2c00059. ISSN 2694-2518. PMC 10125365. PMID 37102088.

- ^ Ueno, Yuichiro; Yamada, Keita; Yoshida, Naohiro; Maruyama, Shigenori; Isozaki, Yukio (March 2006). "Evidence from fluid inclusions for microbial methanogenesis in the early Archaean era". Nature. 440 (7083): 516–9. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..516U. doi:10.1038/nature04584. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16554816. S2CID 4423306.

- ^ Wacey, David; Noffke, Nora; Cliff, John; Barley, Mark E.; Farquhar, James (September 2015). "Micro-scale quadruple sulfur isotope analysis of pyrite from the ∼3480Ma Dresser Formation: New insights into sulfur cycling on the early Earth". Precambrian Research. 258: 24–35. Bibcode:2015PreR..258...24W. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2014.12.012. ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ a b Lollar, Barbara Sherwood; McCollom, Thomas M. (December 2006). "Biosignatures and abiotic constraints on early life". Nature. 444 (7121): E18, discussion E18-9. doi:10.1038/nature05499. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17167427.

- ^ Buick, Roger; Dunlop, J.S.R.; Groves, D.I. (January 1981). "Stromatolite recognition in ancient rocks: an appraisal of irregularly laminated structures in an Early Archaean chert-barite unit from North Pole, Western Australia". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 5 (3): 161–181. Bibcode:1981Alch....5..161B. doi:10.1080/03115518108566999. ISSN 0311-5518.

- ^ Nutman, Allen P.; Bennett, Vickie C.; Friend, Clark R. L.; Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Chivas, Allan R. (2016-08-31). "Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures". Nature. 537 (7621): 535–8. Bibcode:2016Natur.537..535N. doi:10.1038/nature19355. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27580034. S2CID 205250494.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (31 August 2016). "World's Oldest Fossils Found in Greenland". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b Allwood, Abigail C. (22 September 2016). "Evidence of life in Earth's oldest rocks". Nature. 537 (7621): 500–1. doi:10.1038/nature19429. PMID 27580031. S2CID 205250633.

- ^ Zawaski, Mike J.; Kelly, Nigel M.; Orlandini, Omero Felipe; Nichols, Claire I. O.; Allwood, Abigail C.; Mojzsis, Stephen J. (2020-09-01). "Reappraisal of purported ca. 3.7 Ga stromatolites from the Isua Supracrustal Belt (West Greenland) from detailed chemical and structural analysis". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 545 116409. Bibcode:2020E&PSL.54516409Z. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116409. ISSN 0012-821X. S2CID 225256458.

- ^ a b Wei-Haas, Maya (17 October 2018). "'World's oldest fossils' may just be pretty rocks — Analysis of 3.7-billion-year-old outcrops has reignited controversy over when life on Earth began". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Walter, M. R.; Buick, R.; Dunlop, J. S. R. (April 1980). "Stromatolites 3,400–3,500 Myr old from the North Pole area, Western Australia". Nature. 284 (5755): 443–5. Bibcode:1980Natur.284..443W. doi:10.1038/284443a0. S2CID 4256480.

- ^ Philippot, Pascal; Van Zuilen, Mark; Lepot, Kevin; Thomazo, Christophe; Farquhar, James; Van Kranendonk, Martin J. (2007-09-14). "Early Archaean Microorganisms Preferred Elemental Sulfur, Not Sulfate". Science. 317 (5844): 1534–7. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1534P. doi:10.1126/science.1145861. PMID 17872441. S2CID 41254565.

- ^ Awramik, S.M.; Schopf, J.W.; Walter, M.R. (June 1983). "Filamentous fossil bacteria from the Archean of Western Australia". Precambrian Research. 20 (2–4): 357–374. Bibcode:1983PreR...20..357A. doi:10.1016/0301-9268(83)90081-5.

- ^ Hickman-Lewis, Keyron; Westall, Frances; Cavalazzi, Barbara (2019), "Traces of Early Life From the Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa", Earth's Oldest Rocks, Elsevier, pp. 1029–58, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63901-1.00042-3, ISBN 978-0-444-63901-1, S2CID 134488803

- ^ Hofmann, H. J. (2000), Riding, Robert E.; Awramik, Stanley M. (eds.), "Archean Stromatolites as Microbial Archives", Microbial Sediments, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 315–327, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04036-2_34, ISBN 978-3-662-04036-2

- ^ Allwood, Abigail C.; Grotzinger, John P.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Burch, Ian W.; Anderson, Mark S.; Coleman, Max L.; Kanik, Isik (2009-06-16). "Controls on development and diversity of Early Archean stromatolites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9548–55. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9548A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903323106. PMC 2700989. PMID 19515817.

- ^ Duda, Jan-Peter; Kranendonk, Martin J. Van; Thiel, Volker; Ionescu, Danny; Strauss, Harald; Schäfer, Nadine; Reitner, Joachim (2016-01-25). "A Rare Glimpse of Paleoarchean Life: Geobiology of an Exceptionally Preserved Microbial Mat Facies from the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool Formation, Western Australia". PLOS ONE. 11 (1) e0147629. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147629D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147629. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4726515. PMID 26807732.

- ^ Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; slack, John F.; Rittner, Martin; Pirajno, Franco; O'Neil, Jonathan; Little, Crispin T. S. (2 March 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057. S2CID 2420384.

- ^ "Earliest evidence of life on Earth 'found'". BBC News. 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ García-Ruiz, Juan Manuel; Nakouzi, Elias; Kotopoulou, Electra; Tamborrino, Leonardo; Steinbock, Oliver (2017-03-03). "Biomimetic mineral self-organization from silica-rich spring waters". Science Advances. 3 (3) e1602285. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E2285G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1602285. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5357132. PMID 28345049.

- ^ McMahon, Sean (2019-12-04). "Earth's earliest and deepest purported fossils may be iron-mineralized chemical gardens". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1916) 20192410. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2410. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6939263. PMID 31771469.

- ^ Johannessen, Karen C.; McLoughlin, Nicola; Vullum, Per Erik; Thorseth, Ingunn H. (January 2020). "On the biogenicity of Fe-oxyhydroxide filaments in silicified low-temperature hydrothermal deposits: Implications for the identification of Fe-oxidizing bacteria in the rock record". Geobiology. 18 (1): 31–53. Bibcode:2020Gbio...18...31J. doi:10.1111/gbi.12363. hdl:11250/2632364. ISSN 1472-4677. PMID 31532578.

- ^ Wacey, David; Saunders, Martin; Kong, Charlie (April 2018). "Remarkably preserved tephra from the 3430 Ma Strelley Pool Formation, Western Australia: Implications for the interpretation of Precambrian microfossils". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 487: 33–43. Bibcode:2018E&PSL.487...33W. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.01.021.

- ^ Ueno, Yuichiro; Isozaki, Yukio; Yurimoto, Hisayoshi; Maruyama, Shigenori (March 2001). "Carbon Isotopic Signatures of Individual Archean Microfossils(?) from Western Australia". International Geology Review. 43 (3): 196–212. Bibcode:2001IGRv...43..196U. doi:10.1080/00206810109465008. ISSN 0020-6814. S2CID 129302699.

- ^ Wacey, David; Noffke, Nora; Saunders, Martin; Guagliardo, Paul; Pyle, David M. (May 2018). "Volcanogenic Pseudo-Fossils from the ∼3.48 Ga Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. 18 (5): 539–555. Bibcode:2018AsBio..18..539W. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1734. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 5963881. PMID 29461869.

- ^ Tyrell, Kelly April (18 December 2017). "Oldest fossils ever found show life on Earth began before 3.5 billion years ago". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Brasier, Martin D.; Green, Owen R.; Lindsay, John F.; McLoughlin, Nicola; Steele, Andrew; Stoakes, Cris (2005-10-21). "Critical testing of Earth's oldest putative fossil assemblage from the ~3.5Ga Apex chert, Chinaman Creek, Western Australia". Precambrian Research. 140 (1): 55–102. Bibcode:2005PreR..140...55B. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2005.06.008. ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ Pinti, Daniele L.; Mineau, Raymond; Clement, Valentin (2009-08-02). "Hydrothermal alteration and microfossil artefacts of the 3,465-million-year-old Apex chert". Nature Geoscience. 2 (9): 640–3. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..640P. doi:10.1038/ngeo601. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Sugitani, K.; Mimura, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Lepot, K.; Ito, S.; Javaux, E. J. (November 2015). "Early evolution of large micro-organisms with cytological complexity revealed by microanalyses of 3.4 Ga organic-walled microfossils". Geobiology. 13 (6): 507–521. Bibcode:2015Gbio...13..507S. doi:10.1111/gbi.12148. ISSN 1472-4677. PMID 26073280. S2CID 1215306.

- ^ Alleon, J.; Bernard, S.; Le Guillou, C.; Beyssac, O.; Sugitani, K.; Robert, F. (August 2018). "Chemical nature of the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool microfossils". Geochemical Perspectives Letters. 7 (7): 37–42. doi:10.7185/geochemlet.1817. hdl:20.500.12210/9169. S2CID 59402752.

- ^ Condie, Kent C. (2022-01-01), Condie, Kent C. (ed.), "9. The biosphere", Earth as an Evolving Planetary System (F4th ed.), Academic Press, pp. 269–303, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-819914-5.00003-2, ISBN 978-0-12-819914-5, S2CID 262021891, retrieved 2023-11-28

- ^ Finkel, Pablo L.; Carrizo, Daniel; Parro, Victor; Sánchez-García, Laura (May 2023). "An Overview of Lipid Biomarkers in Terrestrial Extreme Environments with Relevance for Mars Exploration". Astrobiology. 23 (5): 563–604. Bibcode:2023AsBio..23..563F. doi:10.1089/ast.2022.0083. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 10150655. PMID 36880883.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Logan, Graham A.; Buick, Roger; Summons, Roger E. (1999-08-13). "Archean Molecular Fossils and the Early Rise of Eukaryotes". Science. 285 (5430): 1033–6. Bibcode:1999Sci...285.1033B. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10446042.

- ^ Waldbauer, Jacob R.; Sherman, Laura S.; Sumner, Dawn Y.; Summons, Roger E. (2009-03-01). "Late Archean molecular fossils from the Transvaal Supergroup record the antiquity of microbial diversity and aerobiosis". Precambrian Research. Initial investigations of a Neoarchean shelf margin–basin transition (Transvaal Supergroup, South Africa). 169 (1): 28–47. Bibcode:2009PreR..169...28W. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2008.10.011. ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ Rasmussen, Birger; Fletcher, Ian R.; Brocks, Jochen J.; Kilburn, Matt R. (October 2008). "Reassessing the first appearance of eukaryotes and cyanobacteria". Nature. 455 (7216): 1101–4. Bibcode:2008Natur.455.1101R. doi:10.1038/nature07381. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 18948954. S2CID 4372071.

- ^ French, Katherine L.; Hallmann, Christian; Hope, Janet M.; Schoon, Petra L.; Zumberge, J. Alex; et al. (2015-04-27). "Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (19): 5915–20. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5915F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4434754. PMID 25918387.

- ^ a b Vinnichenko, Galina; Jarrett, Amber J. M.; Hope, Janet M.; Brocks, Jochen J. (September 2020). "Discovery of the oldest known biomarkers provides evidence for phototrophic bacteria in the 1.73 Ga Wollogorang Formation, Australia". Geobiology. 18 (5): 544–559. Bibcode:2020Gbio...18..544V. doi:10.1111/gbi.12390. ISSN 1472-4677. PMID 32216165. S2CID 214680085.

- ^ Summons, Roger E; Powell, Trevor G; Boreham, Christopher J (1988-07-01). "Petroleum geology and geochemistry of the Middle Proterozoic McArthur Basin, Northern Australia: III. Composition of extractable hydrocarbons". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 52 (7): 1747–63. Bibcode:1988GeCoA..52.1747S. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(88)90001-4. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Love, Gordon D.; Summons, Roger E.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Logan, Graham A.; Bowden, Stephen A. (October 2005). "Biomarker evidence for green and purple sulphur bacteria in a stratified Palaeoproterozoic sea". Nature. 437 (7060): 866–870. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..866B. doi:10.1038/nature04068. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16208367. S2CID 4427285.

- ^ Luo, Qingyong; George, Simon C.; Xu, Yaohui; Zhong, Ningning (2016-09-01). "Organic geochemical characteristics of the Mesoproterozoic Hongshuizhuang Formation from northern China: Implications for thermal maturity and biological sources". Organic Geochemistry. 99: 23–37. Bibcode:2016OrGeo..99...23L. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.05.004.

- ^ Jarrett, Amber J. M.; Cox, Grant M.; Brocks, Jochen J.; Grosjean, Emmanuelle; Boreham, Chris J.; Edwards, Dianne S. (July 2019). "Microbial assemblage and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the 1.38 Ga Velkerri Formation, McArthur Basin, northern Australia". Geobiology. 17 (4): 360–380. Bibcode:2019Gbio...17..360J. doi:10.1111/gbi.12331. PMC 6618112. PMID 30734481.

- ^ Luo, Genming; Hallmann, Christian; Xie, Shucheng; Ruan, Xiaoyan; Summons, Roger E. (2015-02-15). "Comparative microbial diversity and redox environments of black shale and stromatolite facies in the Mesoproterozoic Xiamaling Formation". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 151: 150–167. Bibcode:2015GeCoA.151..150L. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2014.12.022.

- ^ Blumenberg, Martin; Thiel, Volker; Riegel, Walter; Kah, Linda C.; Reitner, Joachim (2012-02-01). "Biomarkers of black shales formed by microbial mats, Late Mesoproterozoic (1.1Ga) Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania". Precambrian Research. 196–197: 113–127. Bibcode:2012PreR..196..113B. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2011.11.010.

- ^ Ragan, Mark A; McInerney, James O; Lake, James A (2009-08-12). "The network of life: genome beginnings and evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1527): 2169–2175. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0046. PMC 2874017. PMID 19571237.

- ^ Weiss, M. C.; Sousa, F. L.; Mrnjavac, N.; Neukirchen, S.; Roettger, M.; Nelson-Sathi, S.; Martin, W. F. (2016). "The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor". Nature Microbiology. 1 (9): 16116. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.116. PMID 27562259. S2CID 2997255.

- ^ a b c Salditt A, Karr L, Salibi E, Le Vay K, Braun D, Mutschler H (March 2023). "Ribozyme-mediated RNA synthesis and replication in a model Hadean microenvironment". Nat Commun. 14 (1): 1495. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.1495S. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37206-4. PMC 10023712. PMID 36932102.

- ^ Berera, Arjun (6 November 2017). "Space dust collisions as a planetary escape mechanism". Astrobiology. 17 (12): 1274–82. arXiv:1711.01895. Bibcode:2017AsBio..17.1274B. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1662. PMID 29148823. S2CID 126012488.

- ^ a b Chan, Queenie H. S.; et al. (10 January 2018). "Organic matter in extraterrestrial water-bearing salt crystals". Science Advances. 4 (1, eaao3521) eaao3521. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.3521C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao3521. PMC 5770164. PMID 29349297.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (19 October 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Associated Press. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Schouten, Lucy (20 October 2015). "When did life first emerge on Earth? Maybe a lot earlier than we thought". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston, Massachusetts: Christian Science Publishing Society. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (2 October 2017). "Life first emerged in 'warm little ponds' almost as old as the Earth itself — Charles Darwin's famous idea backed by new scientific study". The Independent. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Steele, Edward J.; et al. (1 August 2018). "Cause of Cambrian Explosion — Terrestrial or Cosmic?". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 136: 3–23. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2018.03.004. hdl:1885/143614. PMID 29544820. S2CID 4486796.

- ^ McRae, Mike (28 December 2021). "A Weird Paper Tests The Limits of Science by Claiming Octopuses Came From Space". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Martin, William; Baross, John; Kelley, Deborah; Russell, Michael J. (November 2008). "Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 6 (11): 805–814. Bibcode:2008NRvM....6..805M. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1991. ISSN 1740-1534. PMID 18820700.

- ^ "Simulating Early Ocean Vents Shows Life's Building Blocks Form Under Pressure - NASA". 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2025-05-01.

- ^ a b Schopf, J. William (2024-10-21). "Pioneers of Origin of Life Studies-Darwin, Oparin, Haldane, Miller, Oró-And the Oldest Known Records of Life". Life. 14 (10): 1345. Bibcode:2024Life...14.1345S. doi:10.3390/life14101345. ISSN 2075-1729. PMC 11509469. PMID 39459645.

- ^ a b "Miller-Urey experiment | Description, Purpose, Results, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2025-03-05. Retrieved 2025-05-01.

- ^ Kloprogge, Jacob Teunis Theo; Hartman, Hyman (2022-02-09). "Clays and the Origin of Life: The Experiments". Life. 12 (2): 259. Bibcode:2022Life...12..259K. doi:10.3390/life12020259. ISSN 2075-1729. PMC 8880559. PMID 35207546.

- ^ Porada H.; Ghergut J.; Bouougri El H. (2008). "Kinneyia-Type Wrinkle Structures – Critical Review And Model Of Formation". PALAIOS. 23 (2): 65–77. Bibcode:2008Palai..23...65P. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-095r. S2CID 128464944.

External links

[edit]- Vitae (BioLib)

- Biota (Taxonomicon)

- Life (Systema Naturae 2000)

- Wikispecies — a free directory of life

- Life in the Universe — Stephen Hawking (1996)

- Video (24:32): "Migration of Life in the Universe" on YouTube — Gary Ruvkun, 2019.

![Stromatolites may have been made by microbes moving upward to avoid being smothered by sediment.[54][56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Stromatolites_in_Sharkbay.jpg/330px-Stromatolites_in_Sharkbay.jpg)

![Wrinkled Kinneyia-type sedimentary structures formed beneath cohesive microbial mats in peritidal zones.[105]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Runzelmarken.jpg/500px-Runzelmarken.jpg)