Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chitral Expedition

View on Wikipedia

| Chitral Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

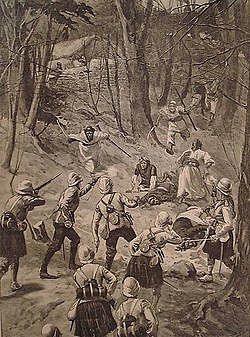

A skirmish during the Chitral expedition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Jandol | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Shuja ul-Mulk |

Umra Khan Sher Afzul Khan Amir ul-Mulk | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,249 (Low Force) 1,400 (Fort & Gilgit force) | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

21 killed, 101 wounded (Low force) 165 killed, 88 wounded (Fort & Kelly force) |

500+ killed (at Malakand Pass only)[2] Unknown but heavy | ||||||

The Chitral Expedition (Urdu:چترال فوجی مہم) was a military expedition in 1895 sent by the British authorities to relieve the fort at Chitral, which was under siege after a local coup following the death of the old ruler. An intervening British force of about 400 men was besieged in the fort until it was relieved by two expeditions, a small one from Gilgit and a larger one from Peshawar.

Background to the conflict

[edit]In the last phase of the Great Game, attention turned to the unclaimed mountainous area north of British India along the later Sino-Russian border. Chitral was thought to be a possible route for a Russian invasion of India, but neither side knew much about the local geography. The British sent people like George W. Hayward, Robert Shaw and probably some Pundits north to explore.

On 18 July 1870, Hayward was attacked, captured and murdered. The ruler of Chitral may have had some involvement in Hayward's murder. From 1871 there were Russian explorers in the Pamir Mountains to the north. Around 1889 some Russians entered Chitral territory as well as Hunza to the east and Gabriel Bonvalot reached Chitral from Russian territory. From around 1876 Chitral was under the protection of the Maharaja of Kashmir to the southeast and therefore in the British sphere of influence but there was no British Resident. At this time Chitrali power extended east to the Yasin Valley about halfway to Hunza. The British established the Gilgit Agency about 175 miles east in 1877. In 1891 the British occupied Hunza north of Gilgit.

From 1857 to 1892 the ruler (Mehtar) was Aman ul-Mulk of the Katoor Dynasty. When the old ruler died in 1892 one of his sons, Afzal ul-Mulk, seized the throne, consolidating his rule by killing as many of his half-brothers as he could.[3] The old ruler's brother, Sher Afzal Khan, who had been in exile at Kabul in Afghanistan about 150 miles southwest, secretly entered Chitral with a few supporters and murdered Afzal ul-Mulk. Another of the old ruler's sons, Nizam ul-Mulk, who had fled to the British at Gilgit, advanced westward from Gilgit, accumulating troops as he went, including 1200 men Sher had sent against him. Seeing the situation was hopeless, Sher fled back to Afghanistan and Nizam took the throne with British blessing and a British political resident called Lieutenant B.E.M Gurdon. Within a year Nizam ul-Mulk was murdered on the orders of his brother, Amir ul-Mulk,[4] while the two were out hunting. Umra Khan, a tribal leader from Bajour to the south marched north with 3,000 Pathans either to assist Amir ul-Mulk or replace him. Surgeon Major George Scott Robertson, the senior British officer at Gilgit, gathered 400 troops and marched west to Chitral and threatened Umra Khan with an invasion from Peshawar if he did not turn back.[3] Amir ul-Mulk began negotiating with Umra Khan so Robertson replaced him with his 12-year-old brother Shuja ul-Mulk. At this point Sher Afzul Khan re-entered the contest. The plan seems to have been that Sher would take the throne and Umra Khan would get part of the Chitral territory. Robertson moved into the fortress for protection which increased local hostility. Since Umra Khan and Sher Afzul continued their march secret messengers were sent out requesting help.

Siege of Chitral

[edit]The Chitral Fort was 80 yards square and built of mud, stone and timber. The walls were 25 feet high and eight feet thick. There was a short covered way to the river, the only water source. The fort held 543 people of whom 343 were combatants including five British officers. The units were the 14th Sikhs and a larger detachment of Kashmiri Infantry. Artillery support was 2 RML 7 pounder Mountain Gun without sights and 80 rounds of ammunition. There were only 300 cartridges per man and enough food for a month. There were trees and buildings near the walls and nearby hills from which sniping was possible with modern rifles. Captain Charles Townshend, later of Mesopotamia fame, commanded the fort.[5]

On 3 March a party was sent out to determine the enemy strength. Its loss was 23 killed and 33 wounded. Harry Frederick Whitchurch was awarded a Victoria Cross for aiding the wounded. At about the same time a small relief force from Gilgit was defeated and the ammunition and explosives they were carrying captured. By 5 April the Chitralis were 50 yards from the walls. On 7 April they set fire to the south-east tower which burned for 5 hours but did not collapse. Four days later the Chitralis began digging a tunnel in order to blow open the fort. The tunnel started from a house where the Chitralis held noisy parties to hide the sounds of digging. By the time sounds of digging were heard it was too late to dig a counter mine. One hundred men rushed out of the eastern gate, found the mouth of the tunnel, bayoneted the miners, blew up the tunnel with explosives[6] and returned with a loss of eight men. On the night of 18 April someone shouted over the wall that the besiegers had fled. The next morning a heavily armed party found that this was true. Kelly's relief force entered Chitral on 20 April and found the besieged "walking skeletons". The siege had lasted a month and a half and cost the defenders 41 lives.

Relief

[edit]

When the British heard of Robertson's situation they began assembling troops around Peshawar, but they were not in a hurry since they assumed that Umra Khan would back down. When reports became more serious they ordered Colonel James Graves Kelly at Gilgit to act. He gathered what troops he could: 400 Sikh Pioneers - mostly road-builders, 40 Kasmiri sappers with 2 Mountain Guns, 900 Hunza Irregulars, all hearty mountain men, and a number of hired coolies to carry the baggage. Although his force was small he had the advantage that the Chitralis did not think that anyone would be fool enough to cross 150 miles of mountains in late winter. He left Gilgit on 23 March, probably up the valley of the Gilgit River, and by 30 March had crossed the snowline at 10,000 feet. Seeing what they were in for, the coolies deserted with their laden ponies but were soon rounded up and kept under guard. The main problem was the 12,000 foot Shandur Pass at the head of the Gilgit River which was crossed in the waist-deep snow dragging mountain guns on sledges (1 to 5 April). Fighting began the next day when the Chitralis became aware of them. By 13 April they had driven the enemy from two main positions and by 18 April the enemy seemed to have disappeared.

Meanwhile, the British had assembled 15,000 men at Peshawar under Major-General Sir Robert Low,[7] with Brigadier General Bindon Blood serving as his Chief of the Staff.[8][9][10] They set off about a week after Kelly left Gilgit. Accompanying Low was Francis Younghusband who was officially on leave and serving as a special correspondent for the London Times.

On 3 April they stormed the Malakand Pass which was defended by 12,000 local warriors. There were significant engagements 2 and 10 days later. On 17 April Umra Khan's men prepared to defend his palace at Munda, but finding themselves greatly outnumbered, they slipped away. Inside the fortress the British found a letter from a Scottish firm offering Maxim guns at 3,700 rupees and revolvers at 34 rupees each. The firm was ordered to leave India. Low was still crossing the Lowari Pass on the day Kelly entered Chitral. Although Kelly got to Chitral first, it was the massive size of Low's force that forced the enemy to withdraw. The first person from Low's force to reach Chitral was Younghusband who, without permission, rode out ahead of the troops. (Max Hastings performed the same stunt in 1982.) That night Younghusband, Robertson, and Kelly shared the garrison's last bottle of brandy.

Aftermath

[edit]

Umra Khan fled with eleven mule-loads of treasure and reached safety in Afghanistan. Sher Afzul ran into one of his foes and was sent into exile in India. Robertson was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India.[11] Kelly was made a Personal aide-de-camp to the Queen and made a Companion of the Order of the Bath. Eleven Distinguished Service Orders (DSOs) were awarded, along with Whitchurch's VC, and all ranks who took part in the siege were given six months extra pay and three months leave.[11] Townshend later became a Major General and at least nine participants became Generals. There was talk of building a road from Peshawar, but this was rejected because of the expense and the fear that the Russians could use the road too. Two battalions were stationed at Chitral and two at the Malakand Pass. In the spring of 1898 Captain Ralph Cobbold was on "hunting leave" in the Pamirs and learned that the Russians had planned to occupy Chitral if the British abandoned it.[12]

British and Indian Army forces who took part received the India Medal with either the clasp Defence of Chitral 1895 or Relief of Chitral 1895.[13]

Chitral remained at peace after 1895 and Shuja ul-Mulk, the 12 year old installed as Mehtar by Robertson, ruled Chitral for the next 41 years until his death in 1936.[14]

Appraisal

[edit]The Chitral Expedition is a much celebrated event, remembered in British history as a chapter in gallantry and valour, which has drawn wide appraisal[clarification needed].[15][16][17]

The valour and endurance displayed by all the ranks in the defence of the fort at Chitral, have added greatly to the prestige of the British arms, and will elicit the admiration of all those who read this account of the gallant defence made by a small party of Her Majesty’s forces, and combined with the troops of His Highness the Maharaja of Kashmir, against heavy odds when shut up in a fort in the heart of an enemy’s country, many miles from succour and support.

The military skill displayed in the conducting of the defence, the cheerful endurance of all the hardship of the siege, the gallant demeanour of the troops and the conspicuous example of heroism and intrepidity recorded, will ever be remembered as forming a glorious episode in the history of the Indian Empire and its army.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ https://www.britishbattles.com/north-west-frontier-of-india/siege-and-relief-of-chitral/ [bare URL]

- ^ "British Intervention in Chitral 1895". onwar.com.

- ^ a b "British Intervention in Chitral 1895". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Harris, John (1975). Much Sounding of Bugles: The Siege of Chitral. Hutchinson. p. 26.

- ^ Younghusband, George John; Younghusband, Sir Francis Edward (1 January 1895). The Relief of Chitral. Macmillan and Company. p. 110.

- ^ Harris, John (1975). Much Sounding of Bugles: The Siege of Chitral. Hutchinson. pp. 211–216.

- ^ Official dispatch of the affair London Gazette

- ^ Fincastle, The Viscount; Eliott-Lockhart, P. C. (2 February 2012). A Frontier Campaign: A Narrative of the Operations of the Malakand and Buner Field Forces, 1897–1898. Andrews UK Limited. p. 55. ISBN 9781781515518.

- ^ Churchill, Winston (1 January 2010). The Story of the Malakand Field Force. Courier Corporation. p. 61. ISBN 9780486474748.

- ^ Raugh, Harold E. (1 January 2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 48. ISBN 9781576079256.

- ^ a b Younghusband, George John; Younghusband, Sir Francis Edward (1 January 1895). The Relief of Chitral. Macmillan and Company. p. 132.

- ^ Harris, John (1975). Much Sounding of Bugles: The Siege of Chitral. Hutchinson. pp. 226–231.

- ^ Joslin, Litherland and Simpkin. British Battles and Medals. pp. 177–178. Published Spink, London. 1988.

- ^ Harris, John (1975). Much Sounding of Bugles: The Siege of Chitral. Hutchinson. p. 231.

- ^ The London Gazette. T. Neuman. 1 January 1895. p. 4006.

- ^ Younghusband, George John; Younghusband, Sir Francis Edward (1 January 1895). The Relief of Chitral. Macmillan and Company. p. 131.

- ^ Barker, A. J. (1 January 1967). Townshend of Kut: a biography of Major-General Sir Charles Townshend. Cassell. p. 80.

Sources

[edit]- The Great Game by Peter Hopkirk, John Murray Ltd. (1990)

- The Relief of Chitral by Major General Sir George J. Younghusband and Sir Francis E. Younghusband, Macmillan & Co (1896)

- With Kelly to Chitral by Major General Sir William G.L. Beynon , Arnold Publishers (1896)

- Campaigns on the North West Frontier by Captain H L Nevill, Naval & Military Press (1912)

- Chitral; the Story of a Minor Siege by Sir George Scott Robertson, KCSI, Methuen Publishing (1898)

- Townshend of Chitral and Kut by Erroll Sherson John (1928)

- Much Sounding of Bugles: The Siege of Chitral 1895, John Harris, Hutchinson (1975)

- The Chitral Campaign: A Narrative of Events in Chitral, Swat and Bajour by Harry Craufuird Thomson, Heinemann Publishers (1895)

- Huttenback, Robert A. "The Siege of Chitral and the “Breach of Faith Controversy”—The Imperial Factor in Late Victorian Party Politics." Journal of British Studies 10.1 (1970): 126-144.

External links

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Henty, George A (1904). Through Three Campaigns A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti. - historical fiction

Chitral Expedition

View on GrokipediaGeopolitical and Historical Background

The Great Game Context

The Great Game referred to the protracted geopolitical contest between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia for dominance in Central Asia from the early 19th century onward, centered on securing influence over intermediary buffer states such as Afghanistan to prevent direct threats to British India.[5] Britain's paramount concern was the incremental Russian expansion southward, which by the 1880s had incorporated vast territories in Central Asia, including Turkestan, raising fears of incursions toward the Indian subcontinent via vulnerable northwestern frontiers.[6] This rivalry manifested in diplomatic maneuvering, intelligence operations, and occasional military posturing, with both powers wary of the other's capacity to destabilize the fragile regional order.[7] Russian military advances in the Pamirs during the early 1890s exemplified the empirical threat, as forces under officers like Colonel Yanov reached positions perilously close to Afghan borders by 1892, prompting British apprehensions of further probing through high-altitude routes into the Hindu Kush.[8] These developments underscored the strategic imperative for Britain to fortify buffer zones, as uncontrolled Russian access could facilitate thrusts toward the Punjab and Indus Valley, exploiting the anarchic tribal polities that offered scant defense against a disciplined imperial army.[7] In response, British policymakers advocated a forward policy of selective agency establishment and alliance-building to monitor and deter such movements, viewing it as pragmatic realism against an expansionist autocracy unencumbered by democratic constraints.[9] Chitral occupied a pivotal position in this calculus, commanding the southern approaches to key Hindu Kush passes—including the Baroghil, Dorah, and Irshad—through which Russian forces might descend into the upper Swat and Dir valleys, thereby threatening the Gilgit Agency and broader Kashmir frontier established in 1889 to counter Pamir encroachments.[10] By maintaining a presence in Chitral, Britain aimed to deny adversaries lateral access across these elevated corridors, which averaged elevations above 4,000 meters and historically served as invasion conduits, while leveraging local mehtarates as proxies in the absence of reliable centralized Afghan control.[6] This defensive orientation prioritized causal containment of Russian momentum over territorial aggrandizement, as evidenced by the reorientation of frontier defenses along the Hindu Kush line following the 1885 Panjdeh crisis, which had nearly precipitated open war.[7]Chitral's Strategic Geography

Chitral consists of a narrow valley traversing the Hindu Kush mountain range along the Chitral River, extending approximately 200 miles from the Baroghil Pass northward to Asmar southward, encompassing an area of about 8,800 square miles.[11] The region is hemmed in by steep mountain barriers with peaks rising to 5,000-6,000 meters, restricting entry primarily to the river corridor or elevated passes that remain snowbound for much of the year.[12] This topography rendered Chitral a natural chokepoint, amplifying its value in imperial calculations by complicating large-scale movements while enabling small forces to dominate access routes. Critical passes underscoring this position include the Lowari Pass to the south at 10,230 feet (3,118 meters), linking Chitral to Dir and the Peshawar valley, and northern outlets such as the Baroghil Pass at roughly 12,000 feet (3,660 meters) and Dorah Pass, which connect to the Wakhan Corridor and Badakhshan regions under potential Russian influence.[13][14] These routes had facilitated historical migrations, trade, and invasions from Central Asia toward the Indian subcontinent, positioning Chitral as a buffer against advances originating beyond the Oxus River.[11] In British strategic assessments around 1895, possession of Chitral served to forestall encirclement of the Punjab by denying invaders alternative paths flanking the Khyber Pass defenses, thereby preserving the integrity of core North-West Frontier fortifications.[15] Furthermore, it secured communications to the Gilgit Agency via the Shandur Pass at 12,400 feet, enabling sustained provisioning and oversight of forward positions abutting Kashmir and vulnerable to northern threats.[11] This configuration underscored Chitral's role in causal chains of regional dominance, where control mitigated risks of coordinated incursions from Afghanistan or Russian proxies exploiting the rugged terrain.Pre-1895 Internal Dynamics in Chitral

Chitral functioned as a semi-independent mehtarate under the Katoor dynasty, characterized by hereditary rule but lacking formalized succession laws, which fostered chronic rivalries among the ruler's sons and extended kin.[16] Aman-ul-Mulk, who ascended in 1857 following his brother's death, consolidated power through military campaigns, including a brief siege of Gilgit against Kashmir and a 1877 treaty acknowledging nominal Kashmiri suzerainty while retaining de facto autonomy.[16] His reign until 1892 maintained relative internal stability by distributing lands to loyal Adamzadas (aristocratic supporters) and foster-relatives, suppressing factional challenges amid expansion into Ghizer, Yasin, and suzerainty over Kafiristan.[17] Aman-ul-Mulk's death on 30 August 1892 triggered immediate succession turmoil, as his second son, Afzal-ul-Mulk, seized the mehtarship while the eldest, Nizam-ul-Mulk, was absent and fled to Gilgit.[17] Afzal-ul-Mulk ruled briefly, eliminating rivals, but was assassinated on 6 November 1892 by his exiled half-brother Sher Afzal, who then proclaimed himself mehtar and garnered support from local factions.[17] [1] British authorities, having re-established the Gilgit Agency in 1889 with garrisons to counter Russian scouting incursions into Chitral and Hunza territories, viewed local instability as a vector for external threats amid the Great Game rivalries.[1] Nizam-ul-Mulk, backed by British agents and Hunza auxiliaries, rallied defecting troops from Sher Afzal's forces and expelled the usurper by December 1892, with Sher Afzal fleeing to Afghan territory.[17] [1] The British did not formally recognize rulers but exerted influence over Chitral's external affairs per agreements dating to 1876, dispatching Surgeon-Major G.S. Robertson on a stabilizing mission in January 1893 to affirm Nizam-ul-Mulk's position and monitor compliance.[17] Parallel pressures arose from Umra Khan of Dir, whose ambitions clashed with Chitral's in June 1892 and escalated when he seized the Narsat fort in September 1892, refusing evacuation despite British warnings against interference in Chitral's internal affairs.[17] Umra Khan's threats toward Drosh highlighted how Dir's expansionist moves intertwined with Chitral's factional feuds, prompting British diplomatic cautions to preserve a buffer against Afghan and Russian advances while avoiding direct entanglement in succession disputes.[17] This precarious equilibrium, reliant on British mediation to check both internal usurpers and neighboring aggressors, underscored Chitral's vulnerability as a fragmented princely state on the imperial frontier.[1]Outbreak of the Crisis

Assassination of Nizam-ul-Mulk

On 1 January 1895, Nizam-ul-Mulk, the British-recognized Mehtar (ruler) of Chitral, was assassinated during a hawking expedition near the Chitral River.[1][2] A retainer fired a shot into his back at the signal of his younger brother, Amir-ul-Mulk, who had orchestrated the killing to claim the throne amid intensifying familial rivalries.[1][18] This fratricide exemplified the endemic instability in Chitral's succession, where the mehtarate—controlled by the Katoor dynasty—was contested through assassination and intrigue rather than formalized inheritance, as multiple sons of the late Aman-ul-Mulk vied for dominance following his death in August 1892.[1][19] Nizam-ul-Mulk's rule, established in late 1892 after British agents at Gilgit supported his expulsion of their uncle Sher Afzal (who had briefly seized power by killing Nizam-ul-Mulk's brother Afzal-ul-Mulk), had provided a veneer of stability backed by imperial influence.[1][3] However, Amir-ul-Mulk, previously spared by Nizam-ul-Mulk despite suspicions of disloyalty, exploited persistent tribal factions loyal to alternative claimants, including those favoring Sher Afzal's return from Afghan exile.[1][18] The killing, occurring in the presence of British political officer Lieutenant Charles Ellis Gurdon and a small escort, underscored the fragility of external stabilization efforts in a region where local power dynamics prioritized kin-based vendettas over imposed order.[1][20] Amir-ul-Mulk immediately proclaimed himself Mehtar, but the regicide eroded the tenuous British-aligned regime, fracturing loyalties among Chitral's Khowar-speaking tribes and paving the way for opportunistic interventions by neighboring powers.[1][18] Historical accounts from British officers emphasize that Nizam-ul-Mulk's death was not merely personal ambition but symptomatic of Chitral's strategic volatility, where rulers maintained authority through alliances with local sardars (chiefs) and external patrons, yet faced constant threats from disaffected relatives leveraging cross-border sanctuaries in Afghanistan or Dir.[1][3] This event directly precipitated a cascade of usurpations, highlighting the limits of British influence in buffering dynastic conflicts without military commitment.[1]Sher Afzul's Usurpation and Umra Khan's Invasion

Sher Afzul, uncle of the assassinated Mehtar Nizam-ul-Mulk and previously exiled in Kabul under Afghan protection, exploited the ensuing power vacuum by secretly returning to Chitral territory in late February 1895, despite the Amir of Afghanistan's assurances to British authorities that he would be detained.[1] Joining forces with Umra Khan of Dir—who had already invaded Chitral in January with 4,000–5,000 tribesmen from Dir and Jandol to back anti-British claimants—Sher Afzul positioned himself at Drosh Fort after its governor surrendered to Umra Khan on 9 February.[1] [21] This alliance, forged on mutual opposition to British influence in the region, allowed Sher Afzul to proclaim himself Mehtar by early March, demanding the withdrawal of British Agent George Robertson and his small garrison from Chitral Fort.[3] Umra Khan's opportunistic incursion stemmed from his prior conquests in Dir and Jandol, where he had displaced local rulers and eyed Chitral's strategic passes as a route to expand influence southward, while harboring ambitions to counter British forward policy amid the Great Game rivalries.[1] His forces, initially numbering around 3,000 but swelling with local recruits proclaiming jihad, advanced northward through heavy snow via the Lowari Pass, capturing key positions like Drosh to sever British supply lines from the south.[3] Sher Afzul's usurpation relied on defections among Chitrali levies loyal to his faction, who viewed the British-backed installation of young Shuja-ul-Mulk as illegitimate, thereby amplifying internal divisions that Umra Khan's intervention militarized.[1] This convergence of familial intrigue and external aggression directly threatened the isolated British garrison of approximately 500 Sikhs, Kashmir Rifles, and locals under Robertson, isolating them amid dwindling supplies and hostile terrain.[1] The crisis underscored how Chitral's chronic succession disputes—exacerbated by Afghan meddling and tribal opportunism—could cascade into broader instability, potentially inviting Russian encroachment through proxies like the Amir, as British intelligence feared a collapse of buffer arrangements in the Hindu Kush.[3] Umra Khan's advance, unhindered until British reinforcements mobilized, highlighted the fragility of diplomatic pacts with semi-independent rulers whose actions prioritized personal gain over regional stability.[1]The Siege of Chitral Fort

Fortification and Initial Garrison Composition

The garrison at Chitral Fort at the onset of the siege on 3 March 1895 consisted of 406 combatants under the political authority of British Agent Surgeon-Major George Scott Robertson, with military command initially held by Captain Campbell of the 4th Kashmir Rifles before he was wounded that day, after which Captain Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend of the Central India Horse assumed control.[3] The fighting force comprised primarily Indian troops from the 14th Sikhs (99 men armed with Martini-Henry rifles) and the 4th Kashmir Rifles (301 men armed with Snider rifles), supplemented by elements of the 4th Gurkha Rifles, 32nd Pioneers from the Gilgit Field Force, and local Punyal levies including Dogras, Punyalis, and Gilgit men.[3] [1] Accompanying the combatants were 137 non-combatants, including 52 Chitralis such as the provisional Mehtar Shuja-ul-Mulk and 85 followers (servants, clerks, and commissariat staff), yielding a total of 543 persons within the fort.[3]| Unit/Ethnic Group | Approximate Strength | Armament |

|---|---|---|

| 14th Sikhs | 99 | Martini-Henry rifles (300 rounds per man) |

| 4th Kashmir Rifles | 301 | Snider rifles (280 rounds per man) |

| 4th Gurkha Rifles and other levies (Dogras, Punyalis, Gilgit men) | Variable, integrated into main force | Small arms |

| Total Combatants | 406 | Small arms only; no artillery |

Conduct of the Siege: Key Phases and Engagements

The siege of Chitral Fort began on 3 March 1895, following the withdrawal of a British-led garrison of approximately 419 fighting men—comprising 99 Sikhs of the 14th Sikhs, 301 Kashmir Imperial Service Troops, and a small number of British officers and locals—into the fort after the defeat of an outnumbered reconnaissance party at Nandai Bend.[1][22] Besieging forces under Sher Afzul, initially around 1,500 Chitralis and Pathans, were soon reinforced by Umra Khan's Jandol levies estimated at 3,000 to 5,000, with total besieger strength reaching up to 10,000 at peak, though active combatants varied.[1][23] Early phases involved repelled rushes on the fort's perimeter, countered by the defenders' use of enfilade fire from fortified positions, which exploited the fort's mud-brick walls and loopholed towers to inflict casualties on exposed attackers.[24] Throughout March, the besiegers maintained pressure through persistent sniping from hastily constructed sangars, while avoiding large-scale assaults due to poor coordination among the tribal contingents, despite their fanaticism.[1] Defenders conducted limited sorties to disrupt enemy positions, and water supply remained precarious, with carriers fetching from the Kunar River under covering fire along Campbell's Covered Way, facing threats of cutoff.[1] By late March, disease outbreaks, including intestinal disorders from contaminated flour ground amid dust and grit, compounded hardships, reducing effective fighting strength.[1] In early April, besiegers escalated with attempts to ignite the Gun Tower on 6 April using flaming arrows and combustibles, which defenders extinguished by 7 April through vigilant firefighting under fire.[1] Mid-month, mining operations commenced, with tunnels dug from the Summer House toward the fort's walls, detected by sounds and vibrations. On 17 April, a daring sortie led by Lieutenant Harley destroyed the primary mine, collapsing the tunnel and killing about 35 besiegers, showcasing the garrison's proactive tactics.[1] These engagements, marked by the defenders' discipline against numerically superior but disorganized foes, sustained the fort until relief, with total garrison casualties at 42 killed and 62 wounded.[1]Defender Tactics and Hardships

The garrison, under the leadership of Political Agent Sir George Scott Robertson—a non-combatant administrator who assumed command following the death of Captain A. B. Campbell—implemented adaptive defensive measures to counter the besiegers' numerical superiority of approximately 12,000 men.[3] Fortifications were improvised by demolishing adjacent outbuildings to deny cover to attackers, creating loopholes in stable walls and towers for enfilading fire, and constructing earth traverses and parados to protect against enfilade and plunging fire.[3] A covered way linked the main fort to the vulnerable water tower, guarded by dedicated posts under reliable native officers, while nightly beacon fires illuminated approaches to deter assaults.[3] Ammunition was conserved through disciplined fire control, with initial stocks of 300 rounds per Martini-Henry rifle and 280 per Snider reduced only as necessary, totaling 213,224 Martini and 68,587 Snider rounds expended by late March.[3] Offensive sorties, such as the 17 April operation led by Lieutenant F. C. Harley with 100 men, proactively destroyed an enemy mining tunnel, inflicting enemy losses while accepting 21 garrison casualties to maintain morale and disrupt siege works.[3] Food and supplies were rationed rigorously from the outset on 3 March, with atta (wheat flour) halved to sustain 543 persons (406 combatants) until mid-June, supplemented by 4 pounds of extra grain per man to avert scurvy after its early onset from vitamin deficiency in the high-altitude, isolated conditions.[3] By 22 March, horseflesh became a staple as stores dwindled, with ghee exhausted after 12 days and overall provisions stretched by the fort's 70-by-70-yard confines, forcing reliance on fatigue parties for daily maintenance amid constant alerts.[3] Snow-blocked passes enforced total isolation, exacerbating psychological strain through unremitting vigilance—men slept in full accoutrements at alarm posts—and physical exhaustion from non-stop duties.[3] Health deteriorated under these privations, with the sick list rising to 60 by 1 April and 85 non-effectives by 9 April, driven by poor sanitation, frostbite (7 cases), snow blindness (35 cases), dysentery, and malaria, though scurvy remained limited due to proactive ration adjustments.[3] Casualties totaled one British officer killed and two wounded by early in the siege, with native ranks suffering 41 killed and 60 wounded overall, reflecting the efficacy of engineered defenses in a 46-day holdout against potential overrun.[3] This resilience stemmed from enforced discipline and Robertson's organizational acumen, enabling the mixed force of 99 14th Sikhs, 301 4th Kashmir Rifles, and local levies to inflict disproportionate enemy losses despite vulnerabilities.[3]Organization of Relief Forces

British Decision-Making and Logistics Challenges

The British Government of India, under Viceroy Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, received news of the Chitral siege on March 7, 1895, prompting immediate authorization for a dual-column relief effort to rescue the garrison and reassert control amid regional instability.[15] This decision reflected strategic imperatives to safeguard imperial prestige—particularly the lives of British officers like Surgeon-Major George Scott and Captain Charles Campbell Townshend—and to forestall potential Russian exploitation of the power vacuum, given Chitral's position as a buffer guarding southern Hindu Kush approaches toward India.[25] Elgin's approval emphasized redundancy in routes: a northern force from Gilgit under Colonel James Kelly to exploit proximity, and a larger southern column under Major-General Robert Low from Peshawar, despite the latter's exposure to greater hazards.[15] Logistical planning confronted severe winter obstacles, including deep snow accumulations rendering the 10,230-foot Lowari Pass virtually impassable and risking frostbite and supply disruptions for thousands of troops.[1] Hostile Pathan tribes in Swat and Dir, emboldened by Umra Khan's influence, posed ambush threats along the southern axis, necessitating preemptive subjugation operations and complicating advance reconnaissance.[26] Mobilization drew from the 1st Division Field Army, assembling approximately 15,000 British and Indian troops supported by 9,000 civilian followers and 30,000 transport animals (mules, camels, and elephants) for artillery and provisions, with primary supply lines extending from Peshawar railheads over 200 miles of rugged terrain lacking roads.[1] [27] Despite these constraints—exacerbated by the onset of the North-West Frontier's harsh spring thaws—administrative foresight enabled rapid concentration of units like the Guides Infantry and Punjab Frontier Force, with stores prepositioned in anticipation of frontier contingencies.[28] Empirical delays in animal procurement and route surveys were offset by the Viceroy's Council prioritizing velocity over caution, underscoring a causal prioritization of decisive intervention to deter adversarial encroachments rather than protracted deliberation.[15] This preparatory phase, spanning late March preparations, underscored the expedition's reliance on imperial logistics networks honed from prior Afghan campaigns, though not without critiques in Parliament over the risks of overextension in unpacified territories.[18]Northern Column: Gilgit Force Advance

The Northern Column, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel James Graves Kelly of the 32nd (Sikh) Punjab Pioneers, departed from Gilgit on March 23, 1895, tasked with advancing southward to relieve the besieged garrison at Chitral Fort. The force comprised approximately 500 troops, primarily from the 32nd Pioneers, supplemented by levies from Hunza and Nagar, along with two 7.7-inch mountain guns and limited transport via ponies and coolies.[1] Facing extreme high-altitude terrain, the column traversed the Gilgit River valley before tackling snowbound passes exceeding 10,000 feet, including the formidable Shandur Pass at around 12,200 feet.[1] By March 30, 1895, the advance had entered deep snow zones, yet the column pressed on, demonstrating exceptional troop endurance amid sub-zero temperatures that caused numerous cases of frostbite and snow-blindness.[1] The Shandur Pass crossing, completed around April 7, involved laborious engineering efforts by the Pioneer regiment to clear paths through heavy drifts, enabling the guns and supplies to follow despite the natural barriers.[1] En route, the force engaged in skirmishes, such as the action at Chakalwat on April 13, where they repelled Pathan irregulars supporting the besiegers, capturing positions with minimal losses.[29] Further progress included the relief of the isolated garrison at Mastuj on April 14, 1895, where Kelly's troops dispersed enemy concentrations drawn northward by the column's approach, preventing their reinforcement of the Chitral siege lines.[1] The rapid 28-day march from Gilgit to Chitral, culminating in arrival on April 20, underscored British logistical ingenuity and soldier resilience, as the advance's momentum critically averted the Chitral defenders' starvation amid dwindling supplies. This northern thrust, independent of southern operations, highlighted the strategic value of high-altitude mobility in frontier campaigns, with the Pioneers' sapping skills proving decisive against impassable winter conditions.[1]Southern Column: Malakand and Swat Operations

The Southern Column, commanded by Major-General Sir Robert Low with Brigadier-General Bindon Blood as chief of staff, assembled approximately 15,000 British and Indian troops, bolstered by 9,000 civilian followers and 30,000 transport animals, to secure the lowland route through Swat and Dir against tribal opposition allied to Umra Khan of Jandol.[1] The force concentrated at Nowshera near Peshawar by late March 1895, with initial movements commencing on 1 April amid challenges from flooded rivers and mobilized Swati lashkars numbering in the thousands.[2] Low's strategy emphasized rapid marches supported by engineer reconnaissance to bridge obstacles, while detachments suppressed scattered Pathan uprisings in the Peshawar Valley to protect supply lines. Advancing into the Swat Valley, the column encountered fierce resistance from Swati tribesmen, who had fortified positions to block access to the Malakand Pass, a critical chokepoint en route to Chitral approximately 200 miles distant.[30] On 3 April 1895, Low's 2nd Brigade, comprising infantry battalions and sappers, launched the Battle of Malakand Pass against an estimated 10,000–12,000 defenders entrenched on the heights with stockades and rifle pits.[31] British tactics integrated mountain artillery fire from 7.7-inch RML guns to disrupt tribal concentrations, followed by coordinated infantry assaults and flanking maneuvers by Gurkha and Sikh units to envelop the pass over five hours of combat.[1] The assault succeeded in capturing the pass by midday, inflicting severe casualties on the lashkars through enfilading fire and bayonet charges, though British losses totaled 11 killed and 51 wounded in the brigade.[31] Subsequent operations involved punitive sweeps to dismantle tribal strongholds in the surrounding hills, employing cavalry patrols for reconnaissance and artillery to deter reinforcements from Bajaur and Dir. These engagements dispersed organized resistance, allowing the column to consolidate at Malakand and extend control southward into Swat proper, where irregular skirmishes with holdout groups were quelled through blockhouse garrisons and tribal fines to prevent ambushes on the extended supply train.[1] By mid-April, the route had been cleared of major threats, demonstrating the efficacy of Low's methodical suppression of valley-based opposition distinct from highland tribal warfare.[32]Lifting the Siege and Immediate Military Resolution

Convergence of Relief Columns

Colonel James Kelly's northern relief column, consisting of around 400 troops from the 32nd Punjab Pioneers, supplemented by approximately 600 Hunza-Nagar levies and two 7.7-inch mountain guns, reached the outskirts of Chitral Fort on April 20, 1895, after a grueling 23-day march from Gilgit that involved crossing snow-bound passes exceeding 12,000 feet.[1][25] Upon Kelly's approach, the besieging force of roughly 10,000-12,000 Chitrali and Dir tribesmen, already demoralized by the prolonged siege and reports of advancing British columns, began to disperse without mounting a coordinated defense, thereby lifting the 46-day encirclement without the fort being breached.[1][25] Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Low's southern relief column, a much larger formation numbering over 10,000 combat troops supported by extensive logistics and artillery, converged at Chitral the following day, April 21, having advanced from the Malakand region through Swat and Dir territories.[25][1] This juncture created an overwhelming British presence that tactically encircled any residual besieger elements, compelling their flight toward the south with only sporadic skirmishes; British casualties during the immediate dispersal phase remained negligible, at under a dozen wounded across both columns.[25][1] The combined strength of Kelly's agile vanguard and Low's reinforced main body—totaling effective combat power far exceeding the disorganized opposition—ensured the siege's empirical resolution through superior mobility and numbers, preserving the garrison's integrity and averting a potentially costly assault on the fort's weakened defenses.[1][25] Minimal pursuit was ordered to avoid unnecessary risks in the rugged terrain, prioritizing consolidation over annihilation of the fleeing tribesmen.[1]Final Engagements and Surrender of Besiegers

Following the arrival of Colonel Kelly's Gilgit relief column at Chitral Fort on 31 March 1895, the besieging army under Sher Afzul disintegrated rapidly, with its disparate Pathan, Chitrali, and Jandol contingents—totaling several thousand—abandoning their positions and fleeing into the surrounding valleys and hills without offering coordinated resistance.[1] The reinforced garrison, now numbering around 600 effectives, conducted limited sorties to secure the immediate environs, but the primary antagonists had already dispersed, leaving behind minimal organized opposition.[4] Sher Afzul, the principal leader of the siege, attempted to escape westward toward Dir territory but was captured on 19 April 1895 near Bashkar by forces loyal to the Khan of Dir, who promptly handed him over to advancing British units from the southern relief column under Major-General Sir Robert Low.[1] This apprehension, effected without significant combat, effectively neutralized the Chitrali faction's command structure, as Afzul's followers had largely melted away during the initial flight, with estimates of thousands deserting en masse to avoid pursuit.[1] Umra Khan of Jandol, whose contingents had bolstered the siege but were partially recalled earlier to contest Low's advance through Swat and Panjkora, evaded capture by fleeing southward into Dir on or about 16 April 1895, eventually crossing into Afghan territory with a portion of his treasure and remaining adherents.[1] British patrols from Kelly's force pursued stragglers in the Laspur and Mastuj sectors, seizing Drosh Fort—previously occupied by Umra Khan's garrisons—on 14 April 1895 after finding it largely abandoned, though minor skirmishes occurred against rearguards at outlying posts like Nisa Gol, resulting in light enemy losses without British fatalities.[4] These actions concluded the mop-up phase, as surviving besieger elements capitulated or submitted to local levies, precluding any renewed threat to the fort.[1]Assessment of Casualties and Fort Damage

During the siege of Chitral Fort from 7 March to 20 April 1895, the garrison of approximately 400 British officers, Indian sepoys, and Kashmiri levies suffered limited casualties, with 5 killed and 19 wounded among the British and Indian troops, primarily from artillery fire and sallies against besieger positions.[1] The low death toll reflected the fort's robust mud-brick walls, which withstood repeated attempts at breaching via mining and rifle fire, though sections were damaged and required repairs using local materials shortly after relief.[1] Across the broader Chitral Expedition, British and Indian forces incurred around 150 fatalities in total, the majority—over 100—occurring during the southern relief column's advance under Major-General Sir Robert Low through hostile Swat and Bajaur territories, where skirmishes against tribal lashkars at sites like the Malakand Pass and Panjkor resulted in heavy close-quarters fighting.[3] The northern Gilgit column under Colonel James Kelly reported fewer losses, with 12 killed during its arduous snow-bound march and minor engagements, underscoring the logistical perils of high-altitude terrain over combat intensity.[1] Material costs to the fort included severe depletion of food stores, reduced to horse fodder and minimal wheat rations by the siege's end, averting starvation only through strict rationing and foraging, while ammunition remained sufficient for defense but not prolonged offense.[1] No total structural loss occurred, as breaches were localized and the citadel intact, contrasting sharply with the expedition's overall modest toll against the risk of fort capitulation, which would have entailed full garrison annihilation and exposure of supply depots to plunder.[3]Political Settlement and Aftermath

Installation of Shuja-ul-Mulk as Mehtar

Following the lifting of the Chitral siege on 20 April 1895, British political agent Major George Robertson addressed the succession crisis by formally installing Shuja-ul-Mulk, the approximately 12-year-old son of the slain Mehtar Aman-ul-Mulk, as the new ruler of Chitral.[1][33] This decision prioritized a young, pliable heir over older rivals to ensure alignment with British and Kashmiri interests, as Shuja-ul-Mulk had demonstrated reliability during the siege.[34] The installation occurred on 1 May 1895 at Chitral Fort, conducted under the nominal suzerainty of the Maharaja of Kashmir, with Robertson acting on behalf of British authorities; during the durbar ceremony, Robertson draped a ceremonial khumkhwab robe over the young Mehtar to symbolize the transfer of authority.[34][33] To consolidate the installation and eliminate immediate threats to the throne, Robertson oversaw the removal of principal rivals, including the deposition and deportation of Amir-ul-Mulk—who had briefly claimed the Mehtarship after Nizam-ul-Mulk's murder—and the rebel leader Sher Afzal, both sent to India under British custody.[35][34] Lesser plotters and supporters faced targeted purges, though broader amnesty was extended to local Chitrali participants in the uprising to foster reconciliation and prevent widespread unrest.[34] Shuja-ul-Mulk ruled initially through a regency council supervised by Robertson, who remained as resident political agent, ensuring administrative continuity and loyalty to external oversight.[33] This swift reordering of Chitral's leadership causally stemmed recurrence of dynastic strife by binding the state to British influence via a dependent minor ruler, thereby securing the northwestern frontier against potential Afghan or independent incursions without requiring permanent large-scale occupation.[34][35] The arrangement proved enduring, with Shuja-ul-Mulk reigning until 1936 under this framework.[33]Establishment of British Protectorate

In the aftermath of the Chitral Expedition's successful relief operations in late April 1895, the British Government of India formalized a protectorate over Chitral to secure the region's passes against potential Russian incursions, establishing institutional mechanisms for oversight. On 4 September 1895, Viceroy Lord Elgin authorized a permanent garrison in Chitral territory, comprising two Indian infantry battalions, one company of sappers and miners, and a mountain battery, primarily stationed at Drosh Fort—a strategically vital position approximately 40 miles south of Chitral town—to project control without directly occupying the Chitral valley's core and thereby reducing tribal antagonism.[20] This military footprint, supported by a political agency under the Gilgit administration, marked the inception of the Chitral Agency in 1895, tasked with administering British interests through a resident assistant political agent.[1] Agreements with the installed Mehtar, Shuja-ul-Mulk, enshrined British suzerainty, obligating Chitral to conduct no independent foreign relations, exclude rival powers from intrigue, and align external policy with British directives, while granting the Mehtar an annual subsidy of 6,000 rupees to sustain his court and forces.[3][27] Internal governance remained ostensibly in the Mehtar's hands, but subject to veto on matters affecting imperial security, effectively curtailing the mehtarate's prior autonomy in diplomacy and defense. This structure integrated Chitral into the British buffer zone along the Afghan frontier, prioritizing empirical control over passes like the Baroghil and Dorah to preempt trans-Hindu Kush threats, as evidenced by the garrison's role in stabilizing supply lines and deterring local levies from external alliances.[3]Expulsion of Umra Khan and Regional Stabilization

Following the successful relief of Chitral Fort on April 20, 1895, British forces under Major General Robert Low advanced into Dir and Jandol to neutralize the threat posed by Umra Khan, the ruler of Jandol who had seized control of Dir and supported the Chitral besiegers with troops.[1] Umra Khan's forces, numbering around 1,200 fighters, confronted the British Second Brigade near the Lowari Pass but were outmaneuvered and dispersed, prompting Umra to abandon his positions and flee eastward with eleven mule-loads of treasure toward Afghan territory by late April 1895.[1] [3] His deposition effectively ended Jandol's expansionist ambitions, with Dir temporarily brought under direct British administration to restore order and reinstall Nawab Mohammad Sharif Khan, the displaced local ruler, as a British-aligned authority.[1] To consolidate control over the southern approaches, British garrisons were established in the Swat Valley, including fortified posts at Malakand Pass and Chakdara, manned by units of the Punjab Frontier Force to deter tribal incursions and maintain the supply line from Peshawar.[1] Local tribes in Swat and Dir, subdued by the expedition's demonstrations of force, agreed to terms including road maintenance obligations and annual tributes equivalent to fines for prior hostilities, totaling several thousand rupees collected from village headmen.[27] These measures, enforced through political agents, quelled immediate unrest without full-scale subjugation. The expulsion and pacification yielded tangible security gains: cross-border raiding from Dir and Jandol into British territories and Chitral declined sharply post-1895, as tribal lashkars avoided confrontation with garrisoned routes.[1] Trade caravans along the Swat-Chitral axis, vital for wool, salt, and access to Gilgit's gem and fur markets, resumed without levy interruptions, stabilizing commerce through the Hindu Kush passes for the ensuing decade.[1] Umra Khan, denied sanctuary claims by Afghan authorities under British diplomatic pressure, remained in exile in Kabul until his death in 1903, preventing any organized revanche.Strategic and Tactical Evaluation

Achievements in Frontier Defense

The rapid advance of Lieutenant-Colonel Kelly's Gilgit column exemplified logistical prowess in securing the North-West Frontier, as 400 rifles of the 32nd (Sikh) Punjab Pioneers, supported by two 7-pounder mountain guns and local Hunza-Nagar levies, traversed approximately 200 miles from Gilgit starting March 23, 1895, crossing the 12,250-foot Shandur Pass amid deep snow to reach Chitral Fort by April 20, after defeating enemy positions at Nisa Gol on April 13.[1][25] This synchronized effort with Major-General Low's larger southern force of 15,000 British and Indian troops, which stormed the Malakand Pass on April 3 against 12,000 tribesmen, ensured the relief of a garrison that had endured a 46-day siege since March 3, demonstrating the Empire's capacity to project power through rugged terrain and sustain supply lines with over 30,000 transport animals.[1][3] Tactical adaptations in mountain warfare proved instrumental, including the use of volley fire and artillery to dismantle fortified sangars during engagements like Chakalwat on April 9, and innovative sorties such as the April 17 destruction of an enemy mine at Chitral Fort using a powder bag, which inflicted significant casualties on besiegers while minimizing defender losses.[1][3] These methods, emphasizing lightly equipped brigades for high-altitude maneuvers and integration of local levies for intelligence and flanking, enhanced British efficacy against numerically superior foes in defiles and passes, laying groundwork for rapid mobilization tactics employed in later frontier operations.[3] The valor of key officers bolstered frontier stability; Political Agent Sir George Scott Robertson coordinated the fort's defense with a garrison of roughly 360, comprising 99 Sikhs of the 14th Sikhs and 261 Kashmir Imperial Service Troops, repelling assaults through fortified loop-holes and countermines until relief arrived.[1][25] Kelly's resolute command in navigating blizzards and enemy ambushes, complemented by Gurkha units in Low's force that secured post-relief garrisons, expelled invaders like Umra Khan's 3,000-8,000 followers by April 19 and dispersed tribal concentrations, thereby reinforcing British prestige and deterring probes along Hindu Kush approaches that could have invited external Russian influence.[3][25] The Sikh and Gurkha troops' discipline under fire contributed decisively to regional pacification, enabling the installation of a pro-British ruler and long-term road security from Peshawar to Chitral.[1][3]Criticisms of Command and Logistics

The southern advance of the Chitral Relief Force under Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Low encountered significant logistical challenges due to the rugged terrain of the Swat Valley and Lowar Agency, necessitating extensive engineering efforts to construct roads, bridges, and supply depots amid uncertain weather conditions from snowmelt and potential early monsoon flooding.[1][3] These delays, while prudent to secure lines of communication over distances exceeding 180 miles from Nowshera base, extended the timeline for the main column's progress beyond initial expectations, with the capture of the Malakand Pass occurring on April 4, 1895, after deliberate preparations rather than rapid assault.[1][2] Command coordination between Low and Brigadier-General Bindon Blood, who led the detached flying column from Dir, involved tensions over pacing, as Blood advocated for accelerated maneuvers to hasten relief, contrasting Low's emphasis on consolidated advances to mitigate risks from tribal ambushes and supply shortages.[11] However, these differences did not escalate to operational breakdown, with Blood's column advancing approximately 100 miles in under two weeks post-Dir, demonstrating effective subordination despite the hierarchical strains inherent in dividing a force of over 15,000 men across irregular paths.[30] The expedition's heavy dependence on irregular levies and local carriers—numbering thousands alongside regular British and Indian troops—exposed vulnerabilities in reliability and endurance, as tribal auxiliaries occasionally faltered under sustained combat or logistical strain, though empirical outcomes showed no catastrophic failures attributable to this composition.[1][3] Contemporary official assessments acknowledged transport deficiencies as a recurring frontier weakness, yet the ultimate relief of Chitral on April 20, 1895, by Colonel James Kelly's independent northern column—independently of Low's slower southern effort—validated the strategy's causal efficacy, rendering post-hoc critiques of delay or command friction largely unsubstantiated by the absence of garrison collapse or strategic loss.[3][1]Breach of Faith Controversy

The Breach of Faith Controversy emerged primarily in parliamentary debates following the Chitral Expedition, focusing on claims that British authorities had extended assurances of neutrality to Umra Khan of Dir prior to his invasion of Chitral in January 1895, only to intervene militarily when he supported Sher Afzal's bid for the mehtarship. Liberal opponents, including figures like Sir William Vernon Harcourt, argued in House of Commons sessions that such diplomatic exchanges implied non-interference in Chitral's internal succession struggles, portraying the subsequent relief expedition as a opportunistic reversal to advance imperial expansion under the Conservative-influenced Viceroy Lord Elgin. These critiques, documented in Hansard records from spring 1895, framed the action as duplicitous, especially given Umra Khan's prior status as a semi-independent ruler whose territories bordered British India. Government rebuttals, articulated by officials such as Secretary of State for India Henry Fowler, countered that no binding pledge of neutrality existed toward an aggressor whose forces, numbering around 4,000-5,000, had besieged British political agent Dr. George Robertson in Chitral Fort from 4 March 1895. On 7 March 1895, the Government of India issued an explicit ultimatum demanding Umra Khan withdraw by 1 April, with military consequences for noncompliance—a warning he disregarded, thereby forfeiting any informal understandings.[38] Empirical records, including telegraphic correspondence, confirm Umra Khan's advance violated British recognition of Chitral's strategic buffer role against Russian influence, rendering prior discussions void under principles of self-preservation where an invader endangers protected personnel and frontier stability.[39] The dispute extended to post-relief decisions, with Liberals decrying the establishment of a permanent garrison as contradicting field proclamations issued during Sir Robert Low's advance, which assured border tribes of temporary transit only for rescue purposes before evacuation.[40] Conservative defenders maintained that evolving intelligence on Russian designs in the Pamirs necessitated retention for causal security—prioritizing verifiable threats over verbal assurances to hostile actors—dismissing Liberal objections as partisan tactics amid the July 1895 general election. This perspective prevailed, bolstering the forward policy without formal censure, as Umra Khan's expulsion to Kabul underscored the primacy of deterrence over disputed diplomacy.[39]Long-Term Legacy

Influence on Durand Line and Frontier Policy

The Chitral Expedition of 1895 reinforced the demarcation of the 1893 Durand Line by securing British control over Chitral, positioning it as a strategic northern anchor guarding the approaches to the Hindu Kush passes and preventing Afghan irredentism in the region.[15] This alignment placed Chitral and adjacent territories, such as those north of the Kabul River, firmly within the British sphere as per the Durand Agreement, countering Afghan claims that sought to reclaim areas like Bajaur, Swat, and Chitral.[41] The expedition's success demonstrated effective British administrative reach, validating the line's role in delineating spheres of influence amid Great Game tensions, without initially intending it as a permanent international boundary.[42] Post-expedition, British policy shifted from prior isolationist tendencies toward a more assertive forward approach, marked by the establishment of a permanent political agency in Chitral under British oversight, which extended influence into tribal buffer zones.[25] This model influenced subsequent applications, such as the forward policy in Waziristan, where permanent posts and subsidies were used to co-opt tribal leaders and preempt incursions, abandoning the strictly defensive "closed border" strategy.[43] The Chitral intervention thus catalyzed a broader commitment to proactive frontier management, with agencies like Gilgit's serving as templates for sustained presence.[15] Empirically, this policy evolution yielded extended stability, with Chitral experiencing no major unrest for over four decades under the installed Mehtar Shuja-ul-Mulk, and the overall frontier seeing reduced large-scale tribal invasions until the 1947 partition, attributable to fortified positions and alliances that deterred coordinated threats.[1] Such outcomes underscored the strategic value of investment in forward agencies over passive demarcation alone.[25]Contribution to Great Game Outcomes

The Chitral Expedition decisively blunted Russian expansionism by securing British dominance over key northwestern passes, preventing the linkage of Russian Pamir positions with Chitral and thereby denying Moscow a potential corridor to the Afghan and Indian frontiers. Russian forces had advanced into the Pamirs during the 1880s and early 1890s, establishing posts that threatened to connect with tribal unrest in Chitral, which bordered Kashmir and the Gilgit Agency; the British response, involving over 15,000 troops under Sir Robert Low, relieved the fort on April 20, 1895, after a grueling march through snow-blocked routes, and expelled invaders aligned with Afghan and local factions potentially amenable to Russian intrigue.[1] This military success demonstrated resolve, compelling Russia to accept the Pamir Boundary Agreement of March 11, 1895, which ceded the eastern Pamirs to China, assigned the Wakhan Corridor to Afghanistan as a neutral buffer, and fixed a demarcation line north of Chitral, averting direct confrontation.[15] By integrating Chitral into a British protectorate, the expedition fortified the Gilgit-Hunza buffer zone, established earlier through the 1891 Hunza-Nagar Campaign, adding depth to defenses against Russian probes via the Hindu Kush and Karakoram ranges. Gilgit's garrison, under Colonel James Kelly, contributed a relief column of 400 men that traversed 200 miles in 20 days to reinforce Chitral from the north, securing supply lines and tribal loyalties in Hunza and Nagar, regions previously contested with Chinese and Russian influences.[1] This layered frontier policy—combining garrisons, subsidies, and political agents—provided empirical strategic insurance, as evidenced by the absence of further Russian incursions post-1895, despite Tsarist autocracy's proven capacity for opportunistic advances in Central Asia.[10] Though the operation incurred high costs, including transport for 10,000 porters and artillery over 300 miles of terrain, it proved causally essential in transitioning the Great Game from rivalry to détente, paving the way for the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention that recognized Afghanistan's neutrality and delimited spheres in Persia and Tibet, stabilizing Eurasia's heartland borders for decades.[3] British imposition of ordered governance in Chitral contrasted with the disorder of unchecked tribal feuds and Russian adventurism, yielding a net gain in frontier security without escalating to open war.Modern Geostrategic Reflections

The strategic position of Chitral, commanding the southern approaches to key Hindu Kush passes such as the Baroghil and Dorah, retained relevance into the 20th and 21st centuries as potential conduits for trade, migration, and military maneuver between South Asia, Afghanistan, and Central Asia.[15][44] These routes, historically used by invaders and caravans, underscored Chitral's role in buffering northern threats, a logic echoed in post-colonial analyses of Wakhan Corridor connectivity for Pakistan and regional powers.[45] While direct use in major 20th-century Afghan conflicts remained limited due to terrain, the passes' capacity for flanking movements or supply lines affirmed their positional value independent of technological shifts.[46] Historiographical assessments diverge, with George Scott Robertson's 1898 official account, drawn from firsthand command during the siege, emphasizing empirical necessities of frontier control over abstract imperial ambition.[34] Revisionist interpretations, often advanced in academic circles prone to systemic biases against colonial efficacy, tend to minimize the expedition as a peripheral overreach, yet primary data— including logistical records of the relief force's 15,000 troops traversing rugged terrain—prioritize causal factors like denying hostile consolidation in pass-adjacent territories.[15] Such views overlook the realist calculus: power projection to secure defensible chokepoints, as evidenced by the expedition's stabilization of Dir and Swat flanks, rather than gratuitous expansion. Critics labeling the effort colonial vanity conflate motive with outcome, ignoring the causal chain wherein inaction risked Russian-aligned proxies exploiting Chitral's vacuum to probe Indian defenses via the Hindu Kush—a threat substantiated by contemporaneous Great Game intelligence.[34] Proponents, grounded in operational records, counter that the intervention's success in installing a pliable ruler and fortifying garrisons yielded measurable deterrence, with enduring lessons in positional realism applicable to modern frontier management amid persistent Afghan instability.[15] This prioritization of geographic determinism over narrative-driven dismissal aligns with verifiable patterns of pass-centric conflict in the region.[44]References

- https://www.[jstor](/page/JSTOR).org/stable/175230

- https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1895-03-21/debates/458b5285-5d3e-4890-baf2-557006197b9d/TheExpeditionToChitral