Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

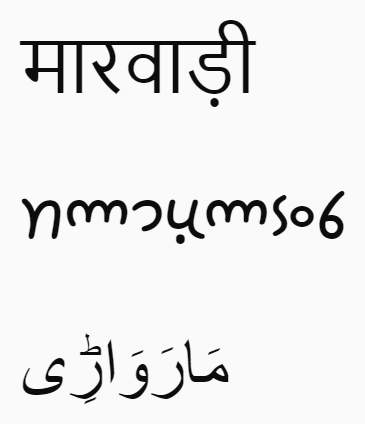

Marwari language

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

| Marwari | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pronunciation | [mɑɾvɑɽi] |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Marwar |

| Ethnicity | Marwari |

Native speakers | 21 million, total count (2011 census)[1] (additional speakers counted under Hindi)[2] |

| Devanagari (in India) Perso-Arabic (in Pakistan) Mahajani (historical) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mwr |

| ISO 639-3 | mwr – inclusive codeIndividual codes: dhd – Dhundarirwr – Marwari (India)mve – Marwari (Pakistan)wry – Merwarimtr – Mewariswv – Shekhawati |

| Glottolog | Noneraja1256 scattered in Rajasthani |

Dark green indicates Marwari speaking home area in Rajasthan, light green indicates additional dialect areas where speakers identify their language as Marwari. | |

Marwari (मारवाड़ी, مارواڑی, Mārwāṛī, IPA: [maɾwaɽi])[a] is a Western Indo-Aryan language belonging to the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Marwari and its closely related varieties like Dhundhari, Shekhawati and Mewari form a part of the broader Rajasthani language family. It is spoken in the Indian state of Rajasthan, as well as the neighbouring states of Gujarat and Haryana, some adjacent areas in eastern parts of Pakistan, and some migrant communities in Nepal.[4][5][6] There are two dozen varieties of Marwari.

Marwari is popularly written in Devanagari script, as are many languages of India and Nepal, including Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, and Sanskrit; although it was historically written in Mahajani, it is still written in the Perso-Arabic script by the Marwari minority in Eastern parts of Pakistan (the standard/western Naskh script variant is used in Sindh Province, and the eastern Nastalik variant is used in Punjab Province), where it has educational status but where it is rapidly shifting to Urdu.[7]

Marwari has no official status in India and is not used as a language of education. Marwari is still spoken widely in Jodhpur, Pali, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Nagaur, and Bikaner. It is also one of the most common languages spoken by Indians in Kenya.

History

[edit]It is believed that Marwari and Gujarati evolved from Old Western Rajasthani or Dingal.[8] Formal grammar of Gurjar Apabhraṃśa was written by Jain monk and Gujarati scholar Hemachandra Suri.[citation needed]

Geographical distribution

[edit]Marwari is primarily spoken in the Indian state of Rajasthan. Marwari speakers have dispersed widely throughout India and other countries but are found most notably in the neighbouring state of Gujarat and in Eastern Pakistan. Speakers are also found in Bhopal. With around 7.9 million speakers in India according to the 2001 census.[9]

Some dialects of Marwari are:[10]

| Dialect | Spoken in |

|---|---|

| Thali/Bikaneri | Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Phalodi, Balotra districts |

| Godwari | Jalore, Sirohi, Sanchore, Pali districts |

| Dhatki | Eastern Sindh and Barmer |

| Shekhawati |

Jhunjhunu, Sikar, Neem ka thana districts |

| Standard Marwari | Ajmer, Beawer, Jodhpur, Kekri, Nagore |

Lexis

[edit]Indian Marwari [rwr] in Rajasthan shares a 50%–65% lexical similarity with Hindi (this is based on a Swadesh 210 word list comparison). It has many cognate words with Hindi. Notable phonetic correspondences include /s/ in Hindi with /h/ in Marwari. For example, /sona/ 'gold' (Hindi) and /hono/ 'gold' (Marwari).

Pakistani Marwari [mve] shares 87% lexical similarity between its Southern subdialects in Sindh (Utradi, Jaxorati, and Larecha) and Northern subdialects in Punjab (Uganyo, Bhattipo, and Khadali), 79%–83% with Dhakti [mki], and 78% with Meghwar and Bhat Marwari dialects. Mutual intelligibility of Pakistani Marwari [mve] with Indian Marwari [rwr] is decreasing due to the rapid shift of active speakers in Pakistan to Urdu, their use of the Arabic script and different sources of support medias, and their separation from Indian Marwaris, even if there are some educational efforts to keep it active (but absence of official recognition by Pakistani or provincial government level). Many words have been borrowed from other Pakistani languages.[7]

Merwari [wry] shares 82%–97% intelligibility of Pakistani Marwari [mve], with 60%–73% lexical similarity between Merwari varieties in Ajmer and Nagaur districts, but only 58%–80% with Shekhawati [swv], 49%–74% with Indian Marwari [rwr], 44%–70% with Godwari [gdx], 54%–72% with Mewari [mtr], 62%–70% with Dhundari [dhd], 57%–67% with Haroti [hoj]. Unlike Pakistani Marwari [mve], the use of Merwari remains vigorous, even if its most educated speakers also proficiently speak Hindi [hin].[11]

| Dialect | Lexical Similarity with Hindi | Phonetic Correspondences |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Marwari [rwr] | 50%–65% | Notable: /s/ in Hindi → /h/ in Marwari (e.g., /sona/ 'gold' → /hono/ 'gold') |

| Pakistani Marwari [mve] | 87% (Southern Sindh) / 79%–83% (Dhakti [mki]) / 78% (Meghwar, Bhat Marwari) | Mutual intelligibility decreasing due to shifts in Pakistan |

| Merwari [wry] | 82%–97% (with Pakistani Marwari [mve]) / 60%–73% (Ajmer, Nagaur) | 58%–80% (Shekhawati [swv]) / 49%–74% (Indian Marwari [rwr]) / 44%–70% (Godwari [gdx]) / 54%–72% (Mewari [mtr]) / 62%–70% (Dhundari [dhd]) / 57%–67% (Haroti [hoj]) |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Pakistani Marwari [mve] | Intelligibility: 82%–97% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Indian Marwari [rwr] | Intelligibility: 49%–74% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Shekhawati [swv] | Intelligibility: 58%–80% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Godwari [gdx] | Intelligibility: 44%–70% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Mewari [mtr] | Intelligibility: 54%–72% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Dhundari [dhd] | Intelligibility: 62%–70% | |

| Merwari [wry] vs. Haroti [hoj] | Intelligibility: 57%–67% |

Phonology

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | ||

| ɪ | ʊ | |||

| Mid | e | ə | o | |

| ɛ | ɔ | |||

| Open | ä | |||

- Nasalization of vowels is phonemic, all of the vowels can be nasalized.[12]

- Diphthongs are /ai, ia, ae, əi, ei, oi, ui, ua, uo/[12]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Post-alv/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | t͡ɕ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | t͡ɕʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | d͡ʑ | ɡ | ||

| breathy | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | d͡ʑʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| implosive | ɓ | ɗ | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Sonorant | rhotic | r | ɽ | ||||

| lateral | w | l | ɭ | j | |||

Morphology

[edit]Marwari languages have a structure that is quite similar to Hindustani (Hindi or Urdu).[citation needed] Their primary word order is subject–object–verb[15][16][17][18][19] Most of the pronouns and interrogatives used in Marwari are distinct from those used in Hindi; at least Marwari proper and Harauti have a clusivity distinction in their plural pronouns.[citation needed]

Vocabulary

[edit]Marwari vocabulary is somewhat similar to other Western Indo-Aryan languages, especially Rajasthani and Gujarati, however, elements of grammar and basic terminology differ enough to significantly impede mutual intelligibility.

Word List

Swadesh 100-word list with Marwari translations and IPA transcriptions, illustrating core vocabulary for linguistic comparison and historical linguistics.

| Sr. No. | Marwari Meaning | IPA | English Word |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | म्हूं | /mʰũː/ | I |

| 2 | थूं | /tʰũː/ | you (singular) |

| 3 | आपण | /aːpəɳ/ | we |

| 4 | ई | /iː/ | this |

| 5 | ऊ | /uː/ | that |

| 6 | कोण | /koːɳ/ | who |

| 7 | के | /keː/ | what |

| 8 | नइ | /nəi/ | not |

| 9 | सगळो | /səgəɭoː/ | all |

| 10 | ढेर | /ɖʰeːɾ/ | many |

| 11 | एक | /eːk/ | one |

| 12 | बी | /biː/ | two |

| 13 | थाळो | /tʰaːɭoː/ | big |

| 14 | लांबो | /laːmboː/ | long |

| 15 | नान्डो | /naːɳɖoː/ | small |

| 16 | औरत | /ɔːɾət/ | woman |

| 17 | मर्द | /mərd̪/ | man (adult male) |

| 18 | आदमी | /aːd̪miː/ | person |

| 19 | माछली | /maːtʃʰliː/ | fish |

| 20 | चिड़ी | /tʃɪɖiː/ | bird |

| 21 | कुक्कुर | /kʊkkʊɾ/ | dog |

| 22 | जूं | /d͡ʒũː/ | louse |

| 23 | रुख | /ɾʊkʰ/ | tree |

| 24 | बीज | /biːd͡ʒ/ | seed |

| 25 | पात | /paːt̪/ | leaf |

| 26 | जड़ | /d͡ʒəɽ/ | root |

| 27 | छाल | /tʃʰaːl/ | bark (of a tree) |

| 28 | चमड़ी | /tʃəmɖiː/ | skin |

| 29 | मास | /maːs/ | meat |

| 30 | लहू | /ləhʊ/ | blood |

| 31 | हड्डी | /ɦəɖɖiː/ | bone |

| 32 | चर्बी | /tʃəɾbiː/ | grease |

| 33 | अंडो | /əɳɖoː/ | egg |

| 34 | सींग | /siːŋ/ | horn |

| 35 | पूंछ | /pũːtʃʰ/ | tail |

| 36 | पांख | /paːŋkʰ/ | feather |

| 37 | केस | /keːs/ | hair |

| 38 | माथो | /maːtʰoː/ | head |

| 39 | कान | /kaːn/ | ear |

| 40 | आँख | /aːnkʰ/ | eye |

| 41 | नाक | /naːk/ | nose |

| 42 | मुख | /mʊkʰ/ | mouth |

| 43 | दांत | /d̪aːnt̪/ | tooth |

| 44 | जिह्वा | /d͡ʒɪɦʋaː/ | tongue |

| 45 | नख | /nəkʰ/ | fingernail |

| 46 | पैर | /pɛːɾ/ | foot |

| 47 | टांग | /ʈaːŋ/ | leg |

| 48 | घुटनो | /ɡʱʊʈʈʰnoː/ | knee |

| 49 | हाथ | /ɦaːt̪ʰ/ | hand |

| 50 | पंख | /pəŋkʰ/ | wing |

| 51 | पेट | /peːʈ/ | belly |

| 52 | आंत | /aːnt̪/ | guts |

| 53 | गरदन | /ɡəɾdən/ | neck |

| 54 | पीठ | /piːʈʰ/ | back |

| 55 | छाती | /tʃʰaːt̪iː/ | breast |

| 56 | दिल | /dɪl/ | heart |

| 57 | कलेजा | /kəleːd͡ʒaː/ | liver |

| 58 | पिऊ | /piːu/ | drink |

| 59 | खाई | /kʰaːi/ | eat |

| 60 | कांट | /kaːɳʈ/ | bite |

| 61 | देख | /d̪eːkʰ/ | see |

| 62 | सुन | /sʊn/ | hear |

| 63 | जाण | /d͡ʒaːɳ/ | know |

| 64 | सूत | /suːt̪/ | sleep |

| 65 | मरी | /məɾiː/ | die |

| 66 | मार | /maːɾ/ | kill |

| 67 | तर | /t̪əɾ/ | swim |

| 68 | उड | /uɖ/ | fly (verb) |

| 69 | चाल | /tʃaːl/ | walk |

| 70 | आव | /aːʋ/ | come |

| 71 | लेट | /leːʈ/ | lie (down) |

| 72 | बैठ | /bɛːʈʰ/ | sit |

| 73 | खड़ो हो | /kʰəɖoː ho/ | stand |

| 74 | दे | /d̪eː/ | give |

| 75 | कह | /kəɦ/ | say |

| 76 | सूरज | /suːɾəd͡ʒ/ | sun |

| 77 | चंद | /tʃənd̪/ | moon |

| 78 | तारा | /t̪aːɾaː/ | star |

| 79 | पानी | /paːniː/ | water |

| 80 | बारिश | /baːɾɪʃ/ | rain |

| 81 | नदी | /nəd̪iː/ | river |

| 82 | तालाब | /t̪aːlaːb/ | lake |

| 83 | समुद्र | /səmʊd̪ɾ/ | sea |

| 84 | लवण | /lʊʋəɳ/ | salt |

| 85 | पाथर | /paːt̪ʰəɾ/ | stone |

| 86 | रेत | /ɾeːt̪/ | sand |

| 87 | धूळ | /d̪ʰuːɭ/ | dust |

| 88 | धरती | /d̪ʰəɾt̪iː/ | earth |

| 89 | बादल | /baːd̪əl/ | cloud |

| 90 | धूआं | /d̪ʰuːãː/ | smoke |

| 91 | आग | /aːɡ/ | fire |

| 92 | राख | /ɾaːkʰ/ | ash |

| 93 | जळ | /d͡ʒəɭ/ | burn |

| 94 | रोड | /ɾoːɖ/ | road |

| 95 | पहाड़ | /pəɦaːɖ/ | mountain |

| 96 | लाल | /laːl/ | red |

| 97 | हरो | /ɦəɾoː/ | green |

| 98 | पीलो | /piːloː/ | yellow |

| 99 | उजळो | /uːd͡ʒəɭoː/ | white |

| 100 | काळो | /kaːɭoː/ | black |

Writing system

[edit]Marwari is generally written in the Devanagari script, although the Mahajani script is traditionally associated with the language. In Pakistan, it is written in the Perso-Arabic script with modifications. Historical Marwari orthography for Devanagari uses other characters in place of standard Devanagari letters.[20]

Perso-Arabic Script

[edit]| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

ا (आ, ा) (ā) [∅]/[ʔ]/[aː] |

ب (ब) (b) [b] |

بھ (भ) (bh) [bʱ] |

ٻ (ॿ) (b̤) [ɓ] |

ٻھ (ॿ़) (b̤h) [ɓʱ] |

پ (प) (p) [p] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

پھ (फ) (ph) [pʰ] |

ت (त) (t) [t̪] |

تھ (थ) (th) [t̪ʰ] |

ٹ (ट) (ṭ) [ʈ] |

ٹھ (ठ) (ṭh) [ʈʰ] |

ث (स) (s) [s] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

ج (ज) (j) [d͡ʒ] |

جھ (झ) (jh) [d͡ʒʱ] |

چ (च) (c) [t͡ʃ] |

چھ (छ) (ch) [t͡ʃʰ] |

ح (ह) (h) [h] |

خ (ख) (kh) [kʰ] ([x]) |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

د (द) (d) [d̪] |

دھ (ध) (dh) [d̪ʱ] |

ڈ (ड) (ḍ) [ɖ] |

ڈھ (ढ) (ḍh) [ɖʱ] |

ذ (ज़) (z) [z] |

ڏ (ॾ) (d̤) [ᶑ] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

ڏھ (ॾ़) (d̤h) [ᶑʱ] |

ر (र) (r) [r] |

رؕ (ड़) (ṛ) [ɽ] |

رؕھ (ढ़) (ṛh) [ɽʱ] |

ز (ज़) (z) [z] |

زھ (ॼ़) (zh) [zʱ] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

ژ (झ़) (zh) [ʒ] |

س (स) (s) [s] |

سھ (स्ह) (sh) [sʰ] |

ش (श) (ś) [ʃ] |

شھ (श्ह) (śh) [ʃʰ] |

ݾ (ष) (x) [χ] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

ݾھ (ष्ह) (xh) [χʰ] |

ص (स) (s) [s] |

ض (ज़) (z) [z] |

ط (त) (t) [t̪] |

ظ (ज़) (z) [z] |

ع (ॽ) ( ’ ) [ʔ] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

غ (ग़) (ġ) [ɣ] ([gʱ]) |

ف (फ़) (f) [f] ([pʰ]) |

ق (क़) (q) [q] ([k]) |

ک (क) (k) [k] |

کھ (ख) (kh) [kʰ] |

گ (ग) (g) [k] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

گھ (घ) (gh) [gʱ] |

ل (ल) (l) [l] |

لھ (ल़ / ल्ह) (lh) [lʰ] |

ݪ (ळ) (ḷ) [ɭ] |

ݪھ (ऴ / ळ्ह) (ḷh) [ɭʰ] |

م (म) (m) [m] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

مھ (म़ / म्ह) (mh) [mʰ] |

ن (न, ङ) (n, ṅ) [n]/[ŋ] |

نھ (ऩ / न्ह) (nh) [nʰ] |

ن٘ـ ں (ं) (◌̃) [◌̃] |

ݨ (ण) (ṇ) [ɳ] |

ݨھ (ण़ / ण्ह) (ṇh) [ɳʰ] |

| Perso-Arabic (Devanagari) (Latin) [IPA] |

و (व) (w) [ʋ] |

ہ (ह) (h) [h] |

ی (ए, ई, े, ी) (e, ī) [j]/[e]/[iː] |

ے (ए, े) (e) [e] |

| Final | Middle | Initial | Devanagari Initial | Devanagari Diacritic | Latin | IPA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ـہ | ـَ | اَ | अ | - | a | [ə] | |

| ـَا / یٰ | ـَا | آ | आ | ा | ā | [aː] | |

| N/A | ـِ | اِ | इ | ि | i | [ɪ] | |

| ـِى | ـِيـ | اِی | ई | ी | ī | [iː] | |

| ـے | ـيـ | اے | ए, ऎ | ॆ, े | e | [eː] | |

| ـَے | ـَيـ | اَے | ऐ | ै | ai | [ɛː] | |

| N/A | ـُ | اُ | उ | ु | u | [ʊ] | |

| ـُو | اُو | ऊ | ू | ū | [uː] | ||

| ـو | او | ओ | ो | ō | [oː] | ||

| ـَو | اَو | औ | ौ | au | [ɔː] | ||

Sample Texts

[edit]Below is a sample text in Marwari, in standard Devanagari Script, and transliterated into Latin as per ISO 15919.[22]

| Devanagari Script | ISO 15919 Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| सगळा मिणख नै गौरव अन अधिकारों रे रासे मांय जळम सूं स्वतंत्रता अने समानता प्राप्त छे। वणी रे गोड़े बुध्दि अन अंतरआत्मा री प्राप्ती छे अन वणी ने भैईपाळा भावना सू एकबीजे रे सारू वर्तन करणो जोयीजै छे। | Sagḷā miṇakh nai gaurav an adhikārõ re rāse māy jaḷam sū̃ svatantrā ane samāntā prāpt che. Vaṇī re goṛe buddhi an antarātmā rī prāptī che an vaṇī ne bhaiīpāḷā bhāvnā sū ekbīje re sārū vartan karṇo joyījai che. | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ also rendered as Marwadi or Marvadi

References

[edit]- ^ Marwari at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Dhundari at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Marwari (India) at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Marwari (Pakistan) at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Merwari at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Mewari at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Shekhawati at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues - 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Ernst Kausen, 2006. Die Klassifikation der indogermanischen Sprachen (Microsoft Word, 133 KB)

- ^ Frawley, William J. (1 May 2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977178-3.

Marwari : also called Rajasthani, Merwari, Marvari. 12,963,000 speakers in India and Nepal. In India: Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, throughout India. Dialects are Standard Marwari, Jaipuri, Shekawati, Dhundhari, Bikaneri.

- ^ Upreti, Bhuwan Chandra (1999). Indians in Nepal: A Study of Indian Migration to Kathmandu. Kalinga Publications. ISBN 978-81-85163-10-9.

- ^ "Marwari Mahotsav 2018". ECS NEPAL. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Pakistani Marwari". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Mayaram, Shail (2006). Against History, Against State. Permanent Black. p. 43. ISBN 978-81-7824-152-4.

The lok gathā (literally, folk narrative) was a highly developed tradition in the Indian subcontinent, especially after the twelfth century, and was simultaneous with the growth of apabhransa, the literary languages of India that derived from Sanskrit and the Prakrits. This developed into the desa bhāṣā, or popular languages, such as Old Western Rajasthani (OWR) or Marubhasa, Bengali, Gujarati, and so on. The traditional language of Rajasthani bards is Dingal (from ding, or arrogance), a literary and archaic form of old Marwari. It was replaced by the more popular Rajasthani (which Grierson calls old Gujarati) that detached itself from western apabhransa about the thirteenth century. This language was the first of all the bhasas of northern India to possess a literature. The Dingal of the Rajasthani bards is the literary form of that language and the ancestor of the contemporary Marvari and Gujarati.

- ^ "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12, 444. ISBN 978-0-521-23420-7.

- ^ "Merwari". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Mukherjee, Kakali (2013). Marwari (Thesis). Linguistic Survey of India LSI Rajasthan.

- ^ Gusain, Lakhan. Marwari (PDF).

- ^ https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/marwari-writing-system-proposal/14928373

- ^ "Indian Marwari". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Dhundari". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Shekhawati". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Mewari". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Haroti". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Pandey, Anshuman (23 May 2011). "Proposal to Encode the Marwari Letter DDA for Devanagari" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Marwari". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Omniglot, Article 1 of the UDHR - Language family: Indo-European: Indo-Iranian https://omniglot.com/udhr/indoiranian.htm

Further reading

[edit]- Lakhan Gusain (2004). Marwari. Munich: Lincom Europa (LW/M 427)

- Mukherjee, Kakali (2011). "Marwari" (PDF).

External links

[edit]Marwari language

View on GrokipediaOverview and Classification

Linguistic Classification

Marwari belongs to the Indo-European language family, more specifically the Indo-Iranian branch, the Indo-Aryan subbranch, the Western Indo-Aryan group, the Rajasthani division, where it functions as a macrolanguage comprising several closely related varieties and subdialects.[2] The language is designated with the ISO 639-3 macrolanguage code mwr, while specific varieties, such as Western Marwari, receive individual codes like rwr; this classification underscores its recognition as a distinct language separate from Hindi or other Central Indo-Aryan tongues. Marwari shares its closest linguistic ties with other Rajasthani varieties, including Mewari and Dhundari, as well as with Gujarati, all forming part of the broader Western Indo-Aryan continuum marked by shared innovations in vocabulary and grammar.[7] It differs from standard Hindi—classified under Central Indo-Aryan—through phonological features like the retention of implosive consonants and aspirated stops not fully paralleled in Hindi, as well as morphological distinctions such as unique pronominal forms and interrogative structures.[8] Linguistic debates on Marwari's status emphasize its separation from Hindi, supported by lexical similarity percentages of 53% to 64% and mutual intelligibility levels below the conventional 80% threshold often used to delineate distinct languages from dialects.[8]Speakers and Status

The 2011 Indian census reported 7.9 million individuals identifying Marwari as their mother tongue, predominantly in Rajasthan (about 7.4 million), though this figure is widely regarded as underreported due to many speakers being subsumed under the broader Hindi category in official classifications. Broader estimates place the total number of Marwari speakers at approximately 45 to 50 million, including those classified under Hindi and diaspora populations.[1][6] The language's vitality is assessed as stable in rural areas of western Rajasthan, where it remains the primary medium of communication, but it faces challenges from language shift toward Hindi in education, media, and urban settings, particularly among younger generations. Ethnologue classifies Marwari as a stable indigenous language, with no formal endangered designation from UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, though some dialects show signs of decline due to urbanization and bilingualism. Efforts to promote vitality include community-based documentation and cultural programs by linguists and local organizations.[4] Marwari lacks official recognition at the national level, as it is not included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which recognizes 22 scheduled languages as of 2025. In Rajasthan, Hindi serves as the official state language, with no designated status for Marwari despite advocacy campaigns. Linguists, activists, and regional bodies have pushed for its inclusion in the Eighth Schedule since the early 2020s, including a 2023-2024 initiative to establish Rajasthani (encompassing Marwari) as a state official language and to advocate for a distinct census category to better capture speaker demographics.[9][10] Diaspora communities maintain significant use of Marwari, particularly among trading networks in Indian cities like Mumbai and Ahmedabad in Gujarat, where it supports ethnic identity and commerce. In Pakistan, Marwari persists among Hindu and Muslim communities in Sindh province, including urban centers like Hyderabad, with speakers numbering in the hundreds of thousands; however, intergenerational transmission is weakening due to shifts toward Sindhi and Urdu.[11]History

Origins and Early Development

The Marwari language traces its origins to the Old Western Rajasthani, also known as Dingal or Maru-Gurjar, which emerged as a distinct variety around the 10th to 12th centuries CE from the Gurjar Apabhramsha Prakrits spoken in the regions of present-day Rajasthan and Gujarat.[12][13] This transitional stage between Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrits and modern Indo-Aryan languages featured phonological and morphological shifts that laid the foundation for Western Rajasthani dialects, including Marwari.[13] Early evidence includes inscriptions from the period, such as those found in Gujarat and Rajasthan border areas, attesting to the use of Old Western Rajasthani. A key milestone in its early standardization occurred in the 12th century when Jain scholar Hemachandra Suri documented the grammar of Gurjar Apabhramsha, a direct precursor to Marwari and related languages, in his work Siddha-Hema-Śabdanuśāsana during the reign of Solanki king Jayasimha Siddharaja (1093–1143 CE).[14] This comprehensive treatise on phonology, morphology, and syntax provided the first systematic description of the linguistic features that would evolve into Marwari and other Western Rajasthani varieties, emphasizing its poetic and literary potential.[15] During the medieval period, Rajasthani languages, including Marwari, absorbed Persian loanwords through interactions with the Delhi Sultanate and later Mughal administration, particularly in administrative and cultural domains, with terms related to governance and trade integrating into the lexicon.[16][17] The language was preserved and developed in oral epics and Dingal poetry, a heroic literary tradition composed by Charan bards that celebrated Rajput valor and history from the 13th to 15th centuries.[18] By the 15th century, Marwari diverged from Gujarati due to geographical barriers posed by the Aravalli hills, which isolated the Marwar region and fostered independent lexical and phonological developments.[13] This separation marked the solidification of Marwari as a distinct dialect within the Rajasthani continuum, distinct from the emerging standard Gujarati in the south.Modern Developments

In the 19th century, Marwari literature began transitioning from the traditional Dingal poetic style, which had dominated medieval Rajasthani expression, to more modern forms incorporating prose and contemporary themes influenced by colonial encounters and social reforms. Key figures like Suryamall Misran (1815–1868) exemplified this shift through works such as Vansa Bhaskara, a historical prose-poetry blend that contributed to modern Rajasthani literature, blending epic narratives with accessible language to address regional identity.[19] This period marked the rise of prose as a vehicle for historical and social commentary, moving away from Dingal's ornate verse toward narrative clarity, though poetry remained prominent.[20] The 20th century saw concerted efforts toward standardization, with the establishment of the Rajasthan Sahitya Akademi in 1958 playing a pivotal role in codifying Marwari grammar and promoting its use in education and literature. Early grammars like Ram Karan Asopa's Marwadi Vyakaran (1896) laid foundational work, while later initiatives, including Sitaram Lalas's multi-volume Rajasthani Sabad Kos (1962–1979), compiled over 200,000 lexical entries to unify dialects.[19] Poets such as Kanhaiyalal Sethia (1919–2008) advanced modern Marwari poetry, blending folk traditions with social activism in collections like Lilasi, fostering a prose-poetry hybrid that resonated with urban audiences.[21] Digital encoding further supported this, as Devanagari script—used for Marwari—gained full Unicode inclusion by the early 2000s, with specific characters like the Marwari DDA (U+0978) added in 2014 to accommodate phonetic nuances.[22] In the 2020s, revitalization initiatives have gained momentum amid ongoing challenges. Vishes Kothari founded the Rajasthani Bhasha Academy in 2021 to teach Marwari through online courses, workshops, and digital content, including translations of folk tales by authors like Vijaydan Detha to engage younger generations.[23] Advocacy for official recognition intensified, with Rajasthani (encompassing Marwari) debated for inclusion in the Constitution's Eighth Schedule during a 2024 Lok Sabha session, where MP Rahul Kaswan highlighted its cultural significance; as of November 2025, efforts continue without resolution.[24] Globalization has accelerated decline through Hindi's dominance in administration and media, reducing intergenerational transmission in urban areas, yet folk media thrives, with YouTube channels like RNS Rajasthani amassing over 248 million views as of November 2025 on songs blending traditional Marwari melodies with modern beats.[23][25]Geographical Distribution and Dialects

Regions Spoken

The Marwari language is predominantly spoken in the Marwar region of western Rajasthan, India, where it serves as the primary vernacular in core districts including Jodhpur, Barmer, Jaisalmer, Pali, Jalore, and Sirohi. Related varieties extend to adjacent districts such as Nagaur (Merwari) and Bikaner (Bikaneri).[26] Beyond Rajasthan, Marwari extends to adjacent areas in Gujarat, particularly the Kutch district, and to northern border regions of Haryana.[27] In eastern Pakistan, communities speaking Marwari are found in the provinces of Sindh and Punjab, often among migrant groups maintaining linguistic ties to their origins.[27] Significant urban concentrations of Marwari speakers occur in Mumbai, driven by the longstanding Marwari business community that has preserved the language through family and commercial networks, as well as in Delhi.[28] A minor presence exists in Nepal's Terai region, linked to cross-border migration.[29] Historical migration patterns along ancient trade routes have established pockets of Marwari speakers in states such as Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, where diaspora communities continue limited use of the language.[27]Dialects and Varieties

The Marwari language encompasses several subdialects, primarily spoken across Rajasthan and adjacent border regions, which exhibit variations in phonology, vocabulary, and grammar while maintaining a high degree of mutual intelligibility among Indian varieties. Major subdialects include Standard Marwari, based on the Jodhpur variety, which serves as the prestige form used in literature, media, and cultural representations. Thali and Bikaneri represent northern varieties, spoken in areas like Bikaner and Jaisalmer, characterized by emphasis on retroflex sounds that distinguish them from central forms. Godwari, a central subdialect found in the Godwar region encompassing Pali, Jalore, and Sirohi districts, features softer consonant articulations and notable phonological traits such as increased vowel nasalization compared to northern varieties. Dhatki, the southern subdialect prevalent in border areas of Barmer, Jaisalmer, and Tharparkar, shows closer affinities to Sindhi through shared lexical and syntactic elements, forming a dialect continuum.[8][30][31] Mutual intelligibility among Indian subdialects is generally high, with recorded-to-text (RTT) comprehension scores ranging from 83% to 97% between Standard Marwari, Godwari, and related forms like Merwari, allowing speakers to communicate effectively despite regional differences. In contrast, intelligibility with Pakistani Marwari varieties, such as those in Sindh, is lower at approximately 82%, dropping further to 60-70% in some cases due to extensive Urdu loanwords and phonological shifts from language contact. These differences highlight the impact of sociolinguistic boundaries on comprehension.[8] Lexical similarity among core Marwari varieties is 76-87%, though it ranges from 70-74% with broader subdialects like Godwari, indicating robust shared vocabulary tempered by regional innovations. Phonological variations contribute to these distinctions; for instance, Godwari exhibits more pronounced vowel nasalization, while Dhatki retains Sindhi-like implosive consonants not as prominent in northern forms. Such metrics underscore the internal cohesion of Marwari as a macrolanguage.[8][32] Standardization remains challenging due to the absence of a universally accepted prestige dialect, with no single variety dominating education or official use across all regions. The Jodhpur-based Standard Marwari, however, is widely employed in media, folk literature, and emerging linguistic development efforts, promoting unity among speakers while accommodating subdialectal diversity.[8]Phonology

Consonants

The Marwari language features a rich consonant inventory of approximately 31 to 32 phonemes, typical of Western Indo-Aryan languages, with a four-way contrast in stops across multiple places of articulation: voiceless unaspirated, voiced unaspirated, voiceless aspirated, and voiced aspirated (breathy-voiced).[33] This system includes bilabial, dental, retroflex, palatal, and velar stops, alongside a distinct retroflex series that sets Marwari apart from neighboring varieties.[33] The full consonant phonemes are presented in the following chart, organized by place and manner of articulation (using IPA notation). The following describes the phonology of standard (Jodhpuri) Marwari; dialects may vary.| Manner/Place | Bilabial | Dental/Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop (voiceless unaspir.) | p | t | ʈ | t͡ɕ (c) | k | |

| Stop (voiced unaspir.) | b | d | ɖ | d͡ʑ (ɟ) | g | |

| Stop (voiceless aspir.) | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | t͡ɕʰ (cʰ) | kʰ | |

| Stop (voiced aspir.) | bʰ | dʰ | ɖʱ | d͡ʑʰ (ɟʰ) | gʰ | |

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Fricative | s | ʂ | h | |||

| Trill/Flap | ɾ | ɽ | ||||

| Lateral approximant | l | ɭ | ||||

| Central approximant | w | j |

Vowels and Suprasegmentals

The vowel system of Marwari features a core inventory of seven to ten oral vowels, depending on the dialect, commonly transcribed as /i, e, ɛ, ə, a, o, u/ with potential distinctions in height such as /ɪ, ʊ, ɔ/ in some varieties.[34] Each of these vowels has a phonemic nasalized counterpart, realized as /ĩ, ẽ, ɛ̃, ə̃, ã, õ, ũ/, where nasalization is a distinctive suprasegmental feature that contrasts meaning; for instance, /mɑ̃/ denotes 'mother' while /mɑ/ refers to 'beat' in certain contexts.[34] In the Bikaner dialect, acoustic analysis confirms eight vowel phonemes, analyzed through formant frequencies (F1-F4) from recordings of native speakers, highlighting their role in speaker identification.[35] Diphthongs in Marwari include /ai, au, ei, ou/, with length distinctions appearing in some dialects, such as long /iː/ versus short /i/ or /ɪ/. These gliding vowels often arise in syllable nuclei and contribute to lexical contrasts, though the exact set varies; for example, additional forms like /əi/ and /ui/ occur in broader inventories.[34] Suprasegmental features emphasize prosody over segmental contrasts. Stress is not phonemically distinctive but typically falls word-initially and serves emphatic functions, with minor pitch variations marking intonation patterns.[34] Questions often exhibit rising pitch accent at the end of utterances, distinguishing them from statements through prosodic cues rather than lexical items.[34] Nasalization, as noted, functions phonemically across positions, extending to diphthongs in some cases. Dialectal variation affects the vowel system significantly. In western dialects like those in Bikaner, vowel length and central /ə/ are prominent, while eastern varieties show more centralized realizations.[36] The Dhatki dialect, transitional to Sindhi influences, incorporates additional diphthongs beyond the core set, enhancing glide complexity.[37] Godwari, a southern variety, exhibits limited vowel harmony, where frontness or backness spreads within words, differing from the more uniform system in standard Marwari.[38]Grammar

Morphology

Marwari nouns inflect for two genders—masculine and feminine—two numbers—singular and plural—and exhibit a direct-oblique case distinction, with the oblique form serving as the base for postpositional phrases. Masculine nouns typically end in -o or -u in the direct singular (e.g., ghoro 'horse'), shifting to -o or -ũ in the oblique, while feminine nouns often end in -ī (e.g., ghori 'mare'). The language displays split ergativity, where the agent of a transitive verb in the perfective aspect receives ergative marking via the postposition -nē, as in rām-nē kitāb pādhi 'Rām read the book'.[39][40][41] Pronouns in Marwari inflect for person, number, gender, and case, with notable distinctions in the first-person plural for clusivity: āmpai for inclusive 'we' (including the addressee) and mhe for exclusive 'we' (excluding the addressee). Second-person pronouns include tu (informal singular), thū̃ (informal plural or honorific), and aap (polite honorific singular or plural). For example, āmpai rākhīe 'Let's keep (it)' contrasts with mhe rākhīe 'We (not you) keep (it)'.[42][41] The verbal morphology of Marwari encompasses a tense-aspect-mood (TAM) system featuring present, past imperfective, past perfective, and future tenses, with verbs agreeing in gender and number with the subject (or object in ergative constructions). Finite verbs conjugate via stem + tense/aspect markers + person-gender-number suffixes; for instance, the perfective form of 'go' is gāũ (masculine singular) or gāī (feminine singular). Compound verbs, combining a non-finite main verb with an auxiliary like kar- 'do', express nuances such as completive aspect, as in bol kar de 'say (it) and finish'.[41][39] Derivational morphology employs suffixes to form new words, such as -ī or -ā for feminines (e.g., deriving ghorī from ghoro) and -panũ for abstracts (e.g., dhan-panũ 'wealth-ABSTRACT' meaning 'richness'). Reduplication serves emphatic or distributive functions, often applying to nouns or verbs, as in rām-rām 'Rāms (many/one after another)'. Diminutives use suffixes like -nī or -ī (e.g., chhorī 'girl' from chhora 'boy/child').[41][40]Syntax

Marwari exhibits a strict subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, characteristic of many Indo-Aryan languages, where the subject precedes the object, and the verb follows both.[40] For instance, a basic declarative sentence like "He goes to school" is structured as wɛ posaɭ ɟawɛ hɛ, with the subject wɛ ('he'), object posaɭ ('school'), and verb ɟawɛ hɛ ('goes is').[40] Unlike prepositional languages, Marwari employs postpositions to indicate spatial, temporal, or relational functions, attaching to the oblique form of nouns; an example is ghar-m ('in the house'), where -m is the postposition for locative case. Verb agreement in Marwari demonstrates split ergativity, a hallmark of New Indo-Aryan languages, where the verb agrees with the subject in imperfective aspects but with the direct object in perfective aspects. In imperfective constructions, such as ongoing or habitual actions, the verb marks person, number, and gender agreement with the nominative subject; for example, a first-person singular imperfective might end in -ũ for masculine subjects. In perfective tenses, the transitive subject takes an ergative marker (often -nē), and the verb agrees with the gender and number of the object, as in māṇ nē rōtī khāī ('The man ate the bread'), where the verb khāī agrees with the feminine singular object rōtī. Adjectives, in contrast, consistently agree with the nouns they modify in gender and number, inflecting for masculine singular (-o), feminine singular (-ī), masculine plural (-e), and feminine plural (-ī̃).[43] Relative clauses in Marwari are formed using correlative constructions, typically introduced by the relative pronoun jo ('who/which/that') in the subordinate clause and resumed by the demonstrative vo ('that') or a pronoun in the main clause.[44] This structure allows the relative clause to precede the main clause, as in jo laṛkī khēl rahī hē, vī lambī hē ('The girl who is playing is tall'), where jo...vī links the clauses without a relative pronoun embedded in the noun phrase.[44] Yes/no questions are often formed by rising intonation or the addition of the particle kyā at the sentence-initial position, while wh-questions use interrogative words like kyā ('what'), kōṇ ('who'), or kadvā ('where'), maintaining SOV order.[45] Negation is primarily achieved through the prefix na- or the particle nā/nã, which precedes the verb or attaches to it, as in nā khāṇā ('do not eat') for imperatives or māṇ nā āyo ('The man did not come') in declaratives.[45] Complex sentence structures in Marwari include serial verb constructions, where multiple verbs chain together to express a single event without conjunctions, often involving a main verb followed by an aspectual or modal auxiliary like dēṇā ('to give') for causatives or benefactives.[46] For example, māṇ pāṇī piyo dē conveys 'The man drinks water (for someone)', with the serial verbs sharing arguments and tense.[46] Conditional clauses are marked by the particle tā or to ('if') introducing the protasis, followed by the apodosis in subjunctive or future form, such as tā bārīsh karē tō khet sīyo ('If it rains, the field will become green'). These constructions allow for nuanced expression of causation, manner, and hypothetical scenarios while adhering to the language's head-final syntax.[46]Lexicon

Core Vocabulary

The core vocabulary of Marwari consists primarily of native Indo-Aryan terms inherited from Sanskrit via Prakrit and Apabhramsha stages, forming the foundational lexicon for everyday communication among its speakers.[47] These words reflect semantic stability in basic concepts, with many retaining phonetic and morphological features traceable to ancient roots, such as the verb for "eat" deriving from Sanskrit khādati through Prakrit forms. High-frequency items in daily discourse, like khaṇo ("eat"), jaṇo ("go"), and khāṇo ("food"), underscore the language's practical orientation toward rural and familial life, often appearing in corpora of spoken Marwari.[48] A representative selection of core vocabulary illustrates Marwari's lexicon, focusing on universal concepts with Indo-Aryan etymologies drawn from compilations like the Swadesh list. For instance, pronouns and numerals show direct inheritance: "I" as mhaṁ or meṁ (from Prakrit mahaṁ), "you" (singular) as tuṁ or tu (Sanskrit tvam), "one" as ek (Sanskrit eka), and "two" as do or be (Sanskrit dva). Natural elements and actions include "water" as paṇi (Sanskrit pānīya), "eat" as khaṇo (Sanskrit khādati), and "father" as bap (Prakrit bāpa).[49][50]| English | Marwari (Devanagari) | IPA/Notes | Etymological Root |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | म्हां / मे | /mə̃/ | Prakrit mahaṁ (Sanskrit aham) |

| You (sg.) | तू | /tu/ | Sanskrit tvam |

| Water | पाणी | /paɳi/ | Sanskrit pānīya |

| Eat | खाणो | /kʰaɳo/ | Sanskrit khādati |

| One | एक | /ek/ | Sanskrit eka |

| Two | दो / बे | /do/ or /be/ | Sanskrit dva |

| Father | बाप | /baːp/ | Prakrit bāpa (Sanskrit pitṛ) |

| Mother | मां / मासा | /maː/ | Sanskrit mātṛ |

| Hand | हाथ | /haːt̪ʰ/ | Sanskrit hasta |

| Foot | पैर / पग | /pəɾ/ or /pəg/ | Sanskrit pāda |

Borrowings and Influences

The Marwari language exhibits substantial lexical borrowings from Persian and Arabic, dating back to the Mughal era when Persian functioned as the administrative and literary language across northern India. These influences permeated Rajasthani varieties, including Marwari, through governance, trade, and cultural exchange, resulting in adopted terms such as kitaab 'book' (from Arabic kitāb) and dost 'friend' (from Persian dūst). Such loanwords often retain their original phonetic forms with minor adaptations to Marwari phonology.[54] Hindi and Urdu have exerted a strong ongoing influence on Marwari, particularly in contemporary domains like education, transportation, and administration. Borrowed terms include ṭreṁ 'train' and iskool 'school', reflecting shared Indo-Aryan roots and media exposure. Lexical similarity between Marwari and Hindi ranges from 50% to 65%, based on Swadesh list comparisons, with Pakistani Marwari varieties showing even closer alignment to Urdu-influenced subdialects due to regional bilingualism.[5] English borrowings have increased in recent decades amid urbanization, globalization, and technological adoption, entering Marwari primarily through urban speech and commerce. Examples encompass kampyũṭar 'computer', mobaail 'mobile phone', paarṭī 'party', and miṭiṅg 'meeting', often phonetically adapted but used interchangeably with native equivalents in informal contexts. These integrations highlight Marwari speakers' multilingualism in professional settings.[40] Conversely, Marwari has contributed to the vocabulary of adjacent languages, notably Gujarati, via extensive trade networks and cultural exchanges in western India. This includes shared terms in commerce and Rajasthani traditions.[55]Writing System

Devanagari Script

The Devanagari script serves as the primary writing system for the Marwari language in India, an abugida with 47 primary characters shared with Hindi and Sanskrit. In this system, each consonant inherently includes the vowel /ə/ (schwa), which can be modified or suppressed using diacritic marks for other vowels, such as अ for /ə/ and इ for /i/. This structure allows for efficient representation of syllables, with the script written from left to right and featuring a horizontal line (shirorekha) atop most characters.[56][57] Marwari adaptations to Devanagari incorporate standard features like the anusvara (ं) to denote nasalization of preceding vowels, enhancing the script's ability to capture the language's frequent nasal sounds. Additionally, the retroflex letter ळ is used to represent the retroflex lateral approximant /ɭ/, a phoneme prominent in Marwari and other Rajasthani varieties, distinguishing it from the dental /l/ (ल) common in Hindi. While no entirely unique letters exist for Marwari, dialectal variations appear in spellings, such as झां to indicate the aspirated affricate /d͡ʑʱ/ followed by a nasalized vowel /ɑ̃/. These adjustments reflect Marwari's phonetic profile without altering the core Devanagari inventory.[40][58] Orthographic conventions in Marwari follow Devanagari norms, including schwa deletion in consonant clusters to simplify writing, as in क्त representing /kt/ rather than an explicit vowel. Standardization has been advanced through educational initiatives by the Rajasthan Board of Secondary Education, which incorporated Rajasthani (encompassing Marwari) as an optional subject in 1973. These efforts aim to unify spelling practices amid regional variations.[59][60] In contemporary usage, Devanagari dominates printed materials, literature, and media for Marwari in India, facilitating its role in cultural expression and informal communication. The script's inclusion in the Unicode standard since version 1.0 in 1991 has supported digital adoption, enabling widespread online presence and software compatibility.[61]Alternative Scripts

Historically, the Marwari language has been recorded using several alternative scripts beyond the dominant Devanagari, particularly in mercantile, literary, and regional contexts. The Mahajani script, a Brahmi-derived abugida developed in the 17th to 19th centuries, served as a primary alternative for Marwari traders across northern India.[62] This cursive script, featuring approximately 30-40 characters optimized for rapid writing, emphasized numeric forms and was extensively employed for trade ledgers, accounts, and business correspondence in Marwari and related languages like Hindi and Punjabi.[3] Its unconnected, simplified glyphs facilitated quick notation in commercial settings but contributed to its obsolescence by the mid-20th century as standardized scripts gained prevalence.[63] Additionally, variants of the Landa script family, characterized by tailless Brahmi-derived forms, appeared in folk writings and merchant records associated with Marwari communities in northwestern India and adjoining regions.[61] These Landa-based systems, lacking a unified standard, were practical for informal and regional documentation but faded with the rise of more formalized writing practices.[64] In contemporary usage, particularly among Marwari speakers in Pakistan, an adapted form of the Perso-Arabic script—drawing from Urdu and Sindhi traditions—remains a viable alternative. This right-to-left abjad incorporates additional letters to accommodate Marwari's retroflex consonants, such as ڑ for the /ɖ/ sound, enabling its application in literature, education, and daily communication within Sindh and other eastern provinces.[61] This script's persistence reflects cultural and linguistic ties to broader Perso-Arabic influences in the region, where it is integrated into local schooling and media.[65] Efforts to revive historical scripts like Mahajani have gained traction in the digital era, supported by its inclusion in the Unicode Standard (version 7.0, 2014), which has enabled the development of fonts and software for archival and cultural preservation projects.[62] Meanwhile, the Perso-Arabic variant continues niche employment in Sindh's educational curricula, sustaining its role for Marwari alongside dominant regional languages.[66]Examples

Sample Texts

One illustrative sample of Marwari is Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which demonstrates the language's formal register and syntactic structure. Devanagari:सगळा मिणख नै गौरव अन अधिकारों रे रासे मांय जळम सूं स्वतंत्रता अने समानता प्राप्त छे। वणी रे गोड़े बुध्दि अन अंतरआत्मा री प्राप्ती छे अन वणी ने भैईपाळा भावना सू एकबीजे रे सारू वर्तन करणो जोयीजै छे।[67] Romanization (ISO 15919):

Sagḷā miṇakh nai gaurav an adhikāroṃ re rāse māṃ jaḷam sūṃ svatantrā ane samāntā prāpta che. Vaṇī re goṛe buddhi an antarātmā rī prāptī che an vaṇī ne bhaiīpāḷā bhāvanā sū ekbīje re sārū vartan karaṇo joyījai che.[67] English Translation:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[68] A literary excerpt from Marwari folk tradition is a short verse from the popular song "Kesariya Balam," a traditional welcome song expressing longing and hospitality, which highlights poetic rhythm and everyday vocabulary. Devanagari:

केसरिया बालम आवोनी, पधारो म्हारे देश जी।

पियाँ प्यारी रा ढोला, आवोनी, पधारो म्हारे देश।

आवण जावण कह गया, तो कर गया मोल अणेर।

गिणताँ गिणताँ घिस गई, म्हारे आंगलियाँ री रेख।[69] Romanization (ISO 15919):

Kesariyā bālam āvoṇī, padhāro mhāre deś jī.

Piāṃ pyārī rā ḍholā, āvoṇī, padhāro mhāre deś.

Āvaṇ jāvaṇ kah gayā, to kara gayā mol aṇer.

Giṇtāṃ giṇtā ghis gaī, mhāre āglīyāṃ rī rekh.[69] English Translation:

Saffron beloved, come, visit our country.

The swing of my dear one, come, visit our country.

He promised to come and go, but made a bargain instead.

Counting and counting, the lines on my fingers have worn away.[70] These samples exemplify Marwari's subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, typical of Indo-Aryan languages, where verbs like "prāpta che" (are obtained) or "karaṇo joyījai" (should do) appear at the sentence end.[71] Case marking relies on postpositions rather than inflectional endings; for instance, "re" indicates genitive or locative relations (e.g., "adhikāroṃ re" for "in rights," "vaṇī re" for "with reason"), while "nai" marks dative (e.g., "miṇakh nai" for "to human beings"), and "sūṃ" denotes ablative origin (e.g., "jaḷam sūṃ" for "from birth").[72] Vocabulary blends native Prakrit-derived terms like "miṇakh" (people) and "vaṇī" (they) with Sanskrit loans such as "gaurav" (dignity), "svatantrā" (freedom), and "buddhi" (reason), reflecting historical influences. In the folk verse, poetic devices include repetition for rhythm ("āvoṇī, padhāro") and metaphors like "kesariyā bālam" (saffron beloved, symbolizing a valorous husband).[61] Recordings of these texts are available online, including an audio rendition of the UDHR Article 1 in Marwari on Omniglot.[73] YouTube channels featuring Rajasthani folk performances also include recitations of "Kesariya Balam" in authentic Marwari dialects.

Common Phrases

Common phrases in Marwari provide essential tools for daily communication, reflecting the language's polite and hospitable nature rooted in Rajasthani culture. These expressions often incorporate honorifics to denote respect, with formal forms using "aap" for elders or strangers and informal "tu" for peers or family. Dialectal variations exist across regions like Jodhpur (Thali dialect) and Bikaner, where pronunciations or word choices may differ slightly, such as "kaiso" becoming "kasan" in some variants.[74][40]Greetings

- Khamma Ghani (खम्मा घणी, kham-maa gha-nee) – Hello or formal greetings, literally meaning "many humbly accept my apologies," used to show humility and respect.[74][75]

- Ram Ram Sa (राम राम सा, raam raam saa) – Informal hello or respectful greeting, often used among acquaintances; it doubles as a farewell.[74][76]

- Aap kaiso ho? (आप कैसो हो?, aap kai-so ho?) – How are you? (formal/polite).[77]

- Tu kaisan hai? (तू कैसन है?, too kai-san hai?) – How are you? (informal).[77]

- Main thik thak hu (मैं ठीक ठाक हूं, main theek thaak hoo) – I am fine.[78]

- Dhanyavad (धन्यवाद, dhan-ya-vaad) – Thank you.[77]

- Subh Raatri (सुभ रात्री, soobh raa-tree) – Good night.[74]

Basic Interactions

- Tharo naam kaain hein? (थारो नाम कैण हे?, thaa-ro naam kaa-in hein?) – What is your name? (polite form).[78]

- Paani deo (पाणी देओ, paa-nee de-o) – Give water (requesting politely).[76]

- Main ghar ja riyo hu (मैं घर जा रियो हूं, main ghar jaa ri-yo hoo) – I am going home.[78]

- Tamme kitho ja ra ho? (तम्मे किथो जा रा हो?, tam-me ki-tho jaa raa ho?) – Where are you going? (polite).[77]

- Su chalyo hai? (सू चल्यो है?, soo chal-yo hai?) – What's up? or What's happening? (informal inquiry).[77]

- Haan (हां, haa-n) – Yes.[76]

- Na (ना, naa) – No.[76]

Cultural Phrases

- Padharo Mhare Des (पधरो म्हारे देश, pad-haa-ro mhaare des) – Welcome to my land, a hospitable invitation often extended to guests.[79]

- Kesariya Balam Aavo Hamare Des (केसरीया बालम आवो हमारे देश, ke-sar-i-yaa baa-lam aa-vo haa-maa-re des) – O saffron-hued beloved, come to our land; a traditional folk expression praising Rajasthan's vibrant culture and inviting visitors.[80]

References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Category:Gujarati_terms_borrowed_from_Marwari

- https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Requests_for_new_languages/Wikipedia_Rajasthani