Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

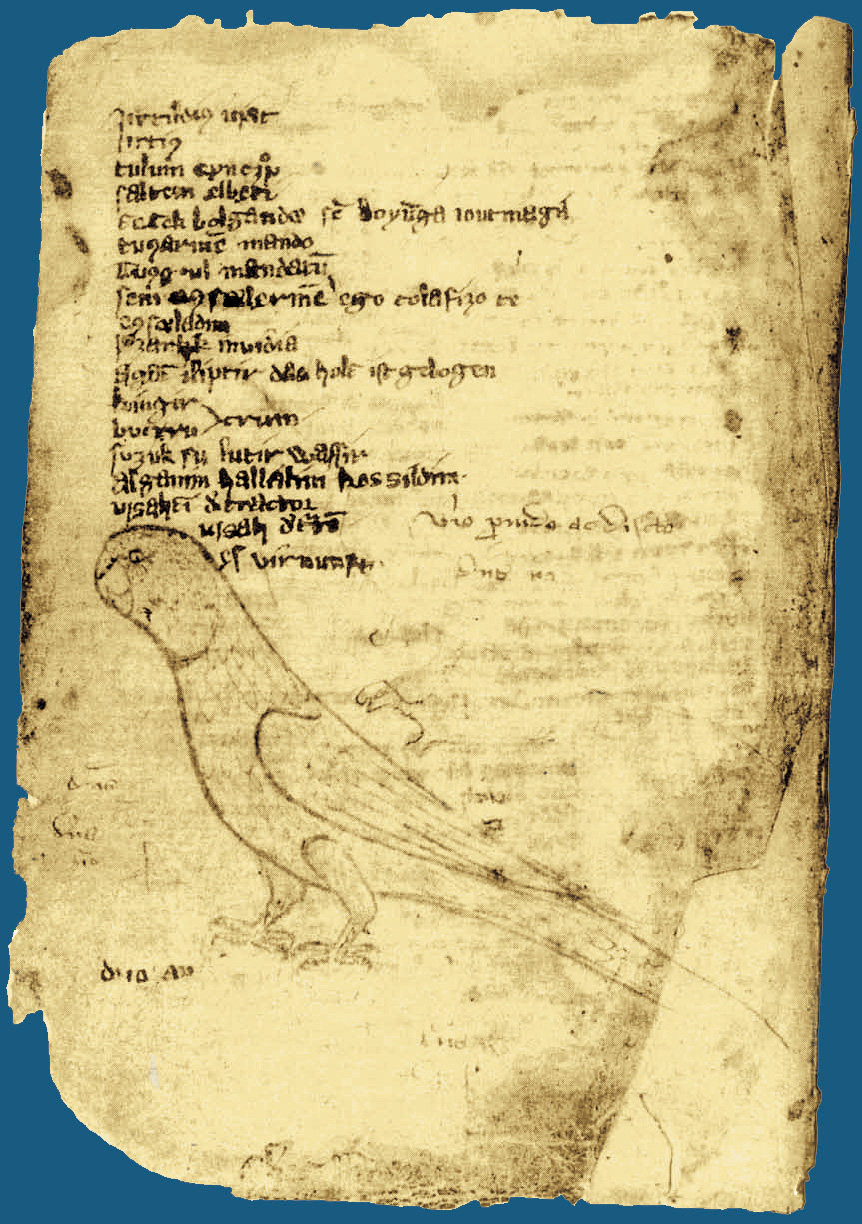

Codex Cumanicus

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2018) |

The Codex Cumanicus is a linguistic manual of the Middle Ages, designed to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cumans, a nomadic Turkic people. It is currently housed in the Library of St. Mark in Venice (BNM ms Lat. Z. 549 (=1597)).

The codex was created in Crimea in 14th century and is considered one of the oldest attestations of the Crimean Tatar language, which is of great importance for the history of Kipchak and Oghuz dialects — as directly related to the Kipchaks (Polovtsy, Kumans) of the Black Sea steppes and particularly the Crimean peninsula.[1]

Origin and content

[edit]It consists of two parts. The first part consists of a dictionary in Latin, Persian and Cuman written in the Latin alphabet, and a column with Cuman verbs, names and pronouns with its meaning in Latin. The second part consists of Cuman-German dictionary, information about the Cuman grammar, and poems belonging to Petrarch.[2] However the codex referred to the language as "Tatar" (tatar til).[3]

The first part of Codex Cumanicus was written for practical purposes, to help learn the language. The second part was written to spread Christianity among the Cumans and different quotes from the religious books were provided with its Cuman translation. In the same section there are words, phrases, sentences and about 50 riddles, as well as stories about the life and work of religious leaders.[2]

The codex likely developed over time. Mercantile, political, and religious leaders, particularly in Hungary, sought effective communication with the Cumans as early as the mid-11th century. As Italian city-states such as Republic of Genoa began to establish trade posts and colonies along the Black Sea coastline, the need for tools to learn the Cuman language sharply increased.

The earliest parts of the codex are believed to have originated in the 12th or 13th century. Substantial additions were likely made over time. The copy preserved in Venice is dated 11 July 1303 on fol. 1r[4] (see Drimba, p. 35 and Schmieder in Schmieder/Schreiner, p. XIII). The codex consists of a number of independent works combined into one.

Riddles

[edit]The "Cuman Riddles" (CC, 119–120; 143–148) are a crucial source for the study of early Turkic folklore. Andreas Tietze referred to them as "the earliest variants of riddle types that constitute a common heritage of the Turkic nations."

Among the riddles in the codex are the following excerpts:[full citation needed]

- Aq küymengin avuzı yoq. Ol yumurtqa.

- "The white yurt has no mouth (opening). That is the egg."

- Kökçä ulahım kögende semirir. Ol huvun.

- "my bluish kid at the tethering rope grows fat, The melon."

- Oturğanım oba yer basqanım baqır canaq. Ol zengi.

- "Where I sit is a hilly place. Where I tread is a copper bowl. The stirrup."

Example

[edit]The codex's Pater Noster reads:

| Cuman |

Atamız kim köktäsiñ. Alğışlı bolsun seniñ atıñ, kelsin seniñ xanlığıñ, bolsun seniñ tilemekiñ — neçik kim köktä, alay [da] yerdä. Kündeki ötmäkimizni bizgä bugün bergil. Dağı yazuqlarımıznı bizgä boşatqıl — neçik biz boşatırbız bizgä yaman etkenlergä. Dağı yekniñ sınamaqına bizni quvurmağıl. Basa barça yamandan bizni qutxarğıl. Amen! |

|---|---|

| English |

Our Father which art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins as we forgive those who have done us evil. And lead us not into temptation, But deliver us from evil. Amen. |

| Crimean Tatar |

Atamız kim köktesiñ. Alğışlı olsun seniñ adıñ, kelsin seniñ hanlığıñ, olsun seniñ tilegeniñ — nasıl kökte, öyle [de] yerde. Kündeki ötmegimizni bizge bugün ber. Daa yazıqlarımıznı (suçlarımıznı) bizge boşat (bağışla) — nasıl biz boşatamız (bağışlaymız) bizge yaman etkenlerge. Daa şeytannıñ sınağanına bizni qoyurma. Episi yamandan bizni qurtar. Amin! |

Codex Cumanicus sources

[edit]- Güner, Galip (2016), Kuman Bilmeceleri Üzerine Notlar (Notes on the Cuman Riddles), Kesit Press, İstanbul. 168 pp.

- Argunşah, Mustafa; Güner, Galip, Codex Cumanicus, Kesit Yayınları, İstanbul, 2015, 1080 pp. (https://www.academia.edu/16819097/Codex_Cumanicus)

- Dr. Peter B. Golden on the Codex

- Italian Part of “Codex Cumanicus”, pp. 1 - 55. (38,119 Mb)

- German Part of “Codex Cumanicus”, pp. 56 - 83. (5,294 Mb)

- Schmieder, Felicitas et Schreiner, Peter (eds.), Il Codice Cumanico e il suo mondo. Atti del Colloquio Internazionale, Venezia, 6-7 dicembre 2002. Roma, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2005, XXXI-350 p., ill. (Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani, Ricerche, 2).

- Drimba, Vladimir, Codex Comanicus. Édition diplomatique avec fac-similés, Bucarest 2000.

- Davud Monshizadeh, Das Persische im Codex Cumanicus, Uppsala: Studia Indoeuropaea Upsaliensia, 1969.

References

[edit]- ^ Garkavets, A.N. [in Russian] (1987). Кыпчакские языки: куманский и армяно-кыпчакский [Kipchak languages: Cuman and Armenian-Kypchak]. Almaty: Наука. p. 18.

Что касается места окончательного формирования сборника, то наиболее вероятной следует считать Кафу — As for the place of the final formation of the manual, Caffa should be considered the most probable ... По диалектным особенностям кодекс считается старейшим памятником крымскотатарского языка, имеющим огромное значение для истории кыпчакских и огузских говоров... — According to the dialectal features, the code is considered the oldest monument of the Crimean Tatar language, which is of great importance for the history of the Kypchak and Oghuz dialects...

- ^ a b [1] Codex Cumanicus (Kumanlar Kitabı)

- ^ Florin Curta (2007). The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars and Cumans. p. 406.

- ^ https://archive.org/details/codexcumanicusbi00kuunuoft/page/n147/mode/2up "MCCCIII die XI Iuly"

External links

[edit]- Codex Cumanicus on-line

- Full text of the Codex Cumanicus in Latin

- Golden, Peter B. "Codex Cumanicus". Provides an in depth overview of the book's content.

- Article in Encyclopædia Iranica: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/codex-cumanicus

- Complete copy of Ligeti's Prolegomena and Kuun's Latin edition and commentary (as published in Budapest, 1981): https://library.hungaricana.hu/hu/view/MTAKonyvtarKiadvanyai_BORB_01/?pg=0&layout=s

- Ligeti's Prolegomena: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23682271