Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

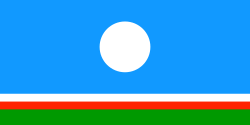

Yakuts

View on Wikipedia

The Yakuts or Sakha (Yakut: саха, saxa; plural: сахалар, saxalar) are a Turkic ethnic group native to North Siberia, primarily the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in the Russian Federation. They also inhabit some districts of the Krasnoyarsk Krai. They speak Yakut, which belongs to the Siberian branch of the Turkic languages.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]According to Alexey Kulakovsky, the Russian word yakut was taken from the Evenki екэ, yekə̄, while Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer claims the Russian word is actually a corruption from the Tungusic form.[4] According to ethnographer Dávid Somfai, the Russian yakut derives from the Buryat yaqud, which is the plural form of the Buryat name for the Yakuts, yaqa.[5] The Yakuts call themselves Sakha, or Urangai Sakha (Yakut: Уран Саха, Uran Sakha) in some old chronicles.[6]

Origin

[edit]Early scholarship

[edit]An early work on the Yakut ethnogenesis was drafted by the Russian Collegiate Assessors I. Evers and S. Gornovsky in the late 18th century. At an unspecified time in the past certain tribes resided around the western shore of the Aral Sea. These peoples later migrated eastward and settled near the Tunka Goltsy mountains of modern Buryatia. Pressure from the expansionist Mongolian Empire later made many of those around the Tunka Goltsy relocate to the Lena River. Several additional Altai-Sayan region tribes later arrived on the Lena to flee from the Mongols. The subsequent cultural melding that occurred between these incoming migrants eventually created the Yakuts. The Sagay Khakas of Abakan River were presented as the origin of the ethnonym Sakha by Evers and Gornovsky.[7][8]

In the mid-19th century, Nikolai S. Schukin wrote "A Trip to Yakutsk" based on his experiences visiting the area. He presented a somewhat different origin of the Yakuts that is based upon local oral histories. Groups of Khakas inhabiting the southern Yenisey watershed migrated north to the Nizhnyaya Tunguska River to the Lena Plateau and finally onward to the Lena River.[9] Schukin is credited as introducing the concept of Yenisey Khakas as the ancestors of the Yakut into Russian historiography.[10] The most authoritative account in support of the Yenisey origin hypothesis was written by Nikolai N. Kozmin in 1928.[11] He concluded that some Khakas moved from the Yenisey to the Angara River due to difficulties in the regional economy. In the 12th century, Buryats arrived at Lake Baikal and through military force pushed the Khakas to the Lena.[12][13]

Lake Baikal

[edit]In 1893, Turkologist scholar Vasily Radlov connected the Kurykans or Gǔlìgān (Chinese: 骨利干) Tiele people from Chinese historical accounts with the Yakuts. They are mentioned as 7th-century tributaries of the Tang dynasty, reportedly living on the Angara and around Lake Baikal. Radlov hypothesized they were a mixture of Tungusic and Uyghur peoples and the forebears of the Yakut.[14]

Khoro

[edit]The Khoro (Khorin, Khorolors,Khori) Yakut maintain their progenitor was Uluu Khoro, rather than Omogoy or Ellei. Scholarship has not definitively established their ancestral ethnic affiliations. Their homeland was somewhere in the south and called Khoro sire. When the Khorolors arrived in the Middle Lena remains uncertain, with scholars estimating from the first millennium to the 16th century AD.[15]

Among scholars a commonly accepted hypothesis is that the Khoro Yakut originate from the Khori Buryat of Lake Baikal,[16][17] and therefore spoke a Turko-Mongolic language.[according to whom?][18] This is largely based on their similar ethnonyms. Proponents see the word Khoro as arising from the Tibetan word hor (Standard Tibetan: ཧོར).[19][20] For example, according to G. N. Runyanstev, during the 6th through 10th centuries CE the inhabitants of Lake Baikal were called Chor.[21] Okladnikov guessed that Khoro sire was near China and adjacent to the X.[vague]

This premise is not universally accepted and has been challenged by some researchers.[22] George de Roerich has argued that the word is based on the Chinese word hu (Chinese: 胡), a term used as general reference by the Chinese to refer to nomadic Mongolic peoples of Central Asia. In contemporary Tibetan hor is used to describe any pastoralist "nomad of mixed origin" regardless of their ethnonym.[23] After researching their origins, Gavriil Ksenofontov concluded that while the Khorolors were "formed from parts of some alien tribe that mixed with the Yakuts", there was no compelling evidence connecting them with the Khori Buryat.[24]

A more recent argument by Zoriktuev proposes that the Khorolors were originally Paleo-Asians from the Lower Amur River.[15] In contrast to their Yakut relatives, Khoro folklore focuses largely on the Raven, with some tales about the Eagle as well. In the mid 18th century Lindenau noted the Khorolors focused their religious devotion on the Raven,[25] who was alternatively referred to as "Our ancestor", "Our deity", and "Our grandfather" by the Khorolors. This reverence arises from the Raven enabling a struggling human (either the first Khoro man or his mother) to survive by giving a flint and tinder box. Their mythos is similar to cultures from both sides of the Bering Sea.[according to whom?] The Haida, Tlingit, Tshisham of the North American Pacific Northwest Coast and the Paleoasians of the Siberian Coast like the Chukchi, Itelmen, and Koryaks all share reverence for the Raven.[26]

Autochthonous ancestry

[edit]Many researchers have concluded that the Yakut ethnogenesis was an admixture of Turks migrating from Lake-Baikal and native Yukaghir and Tungusitic peoples residing around the Lena River.[27][28][29][30] Okladnikov detailed this conceived admixture process as the following:

"...the Turkic-speaking ancestors of the Yakuts not only pushed out the aborigines but also subjected them to their influence by peaceful means; they assimilated and absorbed them into their mass... With this, the local tribes lost the former ethnic name and a proper ethnic consciousness, no longer separating themselves from the mass of Yakuts, and [were] not opposed to them... Consequently, as a result of the mixing with Northern aborigines, the southern ancestors of the Yakuts supplemented their culture and language with new features distinguishing them from other steppe tribes."

Traditional Yakut histories contain stories of the aboriginal peoples of Yakutia. From the subarctic Bulunsky and Verkhoyansky Districts, accounts state that the Black Yukaghir (Yakut: хара дъукаагырдар) descended from migrants pushed north from the Lena River.[31] Related stories recorded in Ust'-Aldanskiy Ulus and Megino-Kangalassky District mention certain tribes leaving the region due to rising pressure from the incoming Yakuts. While some remained and intermarried with the newcomer, most went to the northern tundra.[32]

Ymyyakhtakh

[edit]The Ymyyakhtakh are an ancient people of the Lena River.[according to whom?] A burial ground was excavated[when?] and anthropologists I.I. Gokhman and L.F. Tomtosova studied the human remains and published their results in 1992. They concluded that some of the Late Neolithic population took part in the formation of the modern Yakuts.[33] The consistency of related artistic embellishments on the traditional clothing of the Buryat, Samoyed, and Yakut led one scholar to conclude they are related.[34] Toponymic data of Yakutia indicates there was once a presence of Paleoasian and Samoyed habitation in the region.[35] Vilyui Tumats reportedly practiced anthropophagy and seen as an "ethnocultural marker" of the Samoyedic peoples.[36]

Tumats

[edit]The Tumat stand out in Yakut tradition as a numerous and powerful society, with constant conflict once happening with them on the Vilyuy River.[37] Their households were semi-subterranean with sod roofing and are comparable to traditional Samoyed dwellings.[38] The term Doubo (Chinese: 都播) was used in medieval Chinese historical works in reference to the Sayano-Altai forest peoples. Vasily Radlov concluded that Doubo referred to the Samoyedic peoples.[39] Doubo is additionally seen as the origin of the ethnonym "Tumat" by L. P. Potapov.[40]

The Yakuts called the Tumat people "Dyirikinei" or "chipmunk people" (Yakut: Sдьирикинэй), arising from the Tumatian "tail-coat." Bundles of deer fur were dyed with red ocher and sewn into Tumatian jackets as adornments. Tumat hats were likewise dyed red.[41] This style was likely spread by the Tumatians to some Tungusic peoples. Similar clothing has been reported during the 17th century for the Evenks on the upper Angara and for Evens residing on the lower Kolyma in the early 19th century.[42] Additionally there are many similarities between the clothing of the Tumats and Altaic cultures. Archeological work on Pazyryk culture sites have turned up both hats dyed red and tail-coats made of sables. While the "tails" were not dyed red, they were sewn with red dyed thread. Stylistic and design choices are also comparable to traditional Khakas and Kumandin clothing.[43]

Some peaceable interactions including intermarriage did occur with the Tumats. One such example is the life of Džaardaakh (Russian: Джаардаах), a Tumatian woman. She was renowned for her physical strength and martial repute as an archer. However Džaardaakh eventually married a Yakut man and is considered a notable ancestor of the local Vilyuy Yakut.[44] The origin of her name has been linked to a Yukaghir word for ice (Yukaghir: йархан).[45]

The ancestors of Yakuts were Kurykans who migrated from Yenisey river to Lake Baikal and were subject to a certain Mongolian admixture prior to migration in the 7th century.[46] The Yakuts originally lived around Olkhon and the region of Lake Baikal. Beginning in the 13th century they migrated to the basins of the Middle Lena, the Aldan and Vilyuy rivers under the pressure of the rising Mongols. The northern Yakuts were largely hunters, fishermen and reindeer herders, while the southern Yakuts raised cattle and horses.[47][48]

History

[edit]Imperial Russia

[edit]

In the 1620s, the Tsardom of Muscovy began to move into their territory and annexed or settled down on it, imposed a fur tax and managed to suppress several Yakut rebellions between 1634 and 1642. The tsarist brutality in collection of the pelt tax (yasak) sparked a rebellion and aggression among the Yakuts and also Tungusic-speaking tribes along the River Lena in 1642. The voivode Peter Golovin, leader of the tsarist forces, responded with a reign of terror: native settlements were torched and hundreds of people were killed. The Yakut population alone is estimated to have fallen by 70 percent between 1642 and 1682, mainly because of smallpox and other infectious diseases.[49][50]

In the 18th century the Russians reduced the pressure,[citation needed] gave Yakut chiefs some privileges,[citation needed] granted freedom for all inhabitants,[citation needed] gave them all their lands,[citation needed] sent Eastern Orthodox missions, and educated the Yakut people regarding agriculture.[citation needed] The discovery of gold and, later, the building of the Trans-Siberian Railway, brought ever-increasing numbers of Russians into the region. By the 1820s almost all the Yakuts claimed to have converted to the Russian Orthodox church, but they retained (and still retain) a number of shamanist practices. Yakut literature began to rise in the late 19th century, and a national revival occurred in the early 20th century.

Russian Civil War

[edit]The last conflict of the Russian Civil War, known as the Yakut Revolt, occurred here when Cornet Mikhail Korobeinikov, a White Russian officer, led an uprising and a last stand against the Red Army.

Soviet Union

[edit]In 1922, the new Soviet government named the area the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In the late 1920s through the late 1930s, Yakut people were systematically persecuted, when Joseph Stalin launched his collectivization campaign.[51] It is possible that hunger and malnutrition during this period resulted in a decline in the Yakut total population from 240,500 in 1926 to 236,700 in 1959. By 1972, the population began to recover.[52]

Russian Federation

[edit]

Currently, Yakuts form a large plurality of the total population within the vast Republic of Sakha. According to the 2021 Russian census, there were a total of 469,348 Yakuts residing in the Sakha Republic during that year, or 55.3% of the total population of the Republic.[53]

Culture

[edit]

The Yakuts engage in animal husbandry, traditionally having focused on rearing horses, mainly the Yakutian horse, reindeer and the Sakha Ynagha ('Yakutian cow'), a hardy kind of cattle known as Yakutian cattle which is well adapted to the harsh local weather.[54][55] There is a widespread notion among other ethnic minorities in Russia based on their experience (for example, among geographically close Mongolic Buryats) that the Sakha (i.e. Yakuts) are the least russified ethnic group in Russia and that the knowledge of the native language is widespread, particularly (as is often said) due to the cold and freezing nature of their geographical habitat, and Russians' general avoidance of colonizing those lands.

Certain rock formations named Kigilyakh, as well as places such as Ynnakh Mountain, are held in high esteem by Yakuts.[56]

Cuisine

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

The cuisine of Sakha prominently features the traditional drink kumis, dairy products of cow, mare, and reindeer milk, sliced frozen salted fish stroganina (строганина), loaf meat dishes (oyogos), venison, frozen fish, thick pancakes, and salamat—a millet porridge with butter and horse fat. Kuerchekh (Куэрчэх) or kierchekh, a popular dessert, is made of cow milk or cream with various berries. Indigirka is a traditional fish salad. This cuisine is only used in Yakutia.[citation needed]

Language

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

According to the 2010 census, some 87% of the Yakuts in the Sakha Republic are fluent in the Yakut (or Sakha) language, while 90% are fluent in Russian.[57] The Sakha/Yakut language belongs to the Northern branch of the Siberian Turkic languages. It is most closely related to the Dolgan language, and also to a lesser extent related to Tuvan and Shor.

DNA and genetics analysis

[edit]

The primary Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup for the Yakut is N-M231. While found in around 89% of the general population,[46] in northern Yakutia it is closer to 82%. N-M231 is shared with various other Eastern Siberian populations.[58] The remaining haplogroups are approximately: 4% C-M217 (including subclades C-M48 and C-M407), 3.5% R1a-M17 (including subclade R1a-M458), and 2.1% N-P43, with sporadic instances of I-M253, R1b-M269, J2, and Q.[59][58]

According to Adamov, haplogroup N1c1 makes up 94% of the Sakha population. This genetic bottleneck has been dated approximately to 1300 CE ± 200 ybp and speculated to have been caused by high mortality rates in warfare and later relocation to the Middle Lena River.[60]

The primary mitochondrial DNA haplogroups are various East Asian lineages, making up 92% of the total: haplogroup C at 36% to 45.7% and haplogroup D at 25.7% to 32.9% of the Yakut.[58] Minor Eastern Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups include: 5.2% G, 4.49% F, 3.55% M13a1b, 1.89% A, 1.18% Y1a, 1.18% B, 0.95% Z3, and 0.71% M7.[58] According to Fedorova, besides East Asian maternal lineages, "the mtDNA pool of the native populations of Sakha contains a small (8%), but diverse set of western Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups, mostly present among Yakuts and Evenks", the most common being H and J.[58]

Notable people

[edit]Academia

[edit]- Eduard Yefimovich Alekseyev, ethnomusicologist

- Georgiy Basharin, professor at the Yakutsk State University

- Zoya Basharina, professor at Yakutsk State University

- Gavriil Ksenofontov, researcher at Irkutsk State University

- Semyon Novgorodov, linguist

Arts

[edit]- Evgenia Arbugaeva, photographer, Oscar-nominated director

Cinema and Television

[edit]- Anna Kuzmina, actress

Entrepreneurship

[edit]- Arsen Tomsky, founder and CEO of the international ride-hailing service inDrive

Military

[edit]- Valery Kuzmin, Soviet pilot

- Fyodor Okhlopkov, was a Soviet sniper

- Vera Zakharova, was a Po-2 air ambulance pilot in the Soviet Air Force during World War II

Models

[edit]Musicians

[edit]Politicians

[edit]- Maksim Ammosov

- Sardana Avksentyeva

- Isidor Barakhov

- Yegor Borisov

- Alexandra Ovchinnikova

- Platon Oyunsky

- Aysen Nikolayev

- Mikhail Nikolayev

- Yekaterina Novgorodova

- Fedot Tumusov

Rulers

[edit]- Tygyn Darkhan, ruler of the Yakuts

Sports

[edit]- Georgy Balakshin, boxer

- Roman Dmitriyev, former Soviet wrestler and Olympic champion

- Vasilii Egorov, boxer

- Vasily Gogolev, wrestler

- Eduard Grigorev, freestyle wrestler for Poland

- Gavril Kolesov, checkers player

- Pavel Pinigin, former Soviet wrestler and Olympic champion

Writers

[edit]- Albina Borisova, theatrical translator

- Natalia Kharlampieva, poet

- Sardana Oyunskaya, folklorist

- Aita Shaposhnikova, translator and critic

- Anastasia Syromyatnikova, writer

- Pyotr Toburokov, poet and children's writer

Other

[edit]- Alexander Gabyshev, political dissident

Diaspora

[edit]The Sakha American Cultural Association, a non-profit organization established in Seattle, Washington in 2024 [61]

"The Sakha people had made a temporary footprint in the U.S. in 1820 at Fort Ross [62] in Jenner, California. According to the 1820 census,[63] five Sakha men lived in the fort with 260 people, working for the Russian-American Company, a fur-trading business. This fort became a melting pot of different cultures, including Russians, Native Alaskans and local Native American tribes, such as the Kashaya Pomo. The Sakha were part of the diverse workforce that supported the fort operations in areas, such as hunting, trapping, farming and construction. By 1860, there were at least 20 Sakhas living at Fort Ross before the Russian-American Company ended its North American operations in the early 1880s." - Lynnwood Today [61]

See also

[edit]- Aisyt (Ajysyt/Ajyhyt), the name of the mythic mother goddess of the Sakha people

- Kurumchi culture

- Yakutian horse

References

[edit]- ^ Russia 2010a.

- ^ USB 2020.

- ^ CAS 2021.

- ^ Balzer, Marjorie (1995). Culture incarnate: native anthropology from Russia. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. p. 25. ISBN 1-56324-535-3.

- ^ Kara, Dávid Somfai (2018). "The Formation of Modern Turkic 'Ethnic' Groups in Central and Inner Asia". The Hungarian Historical Review. 7 (1): 98–110. ISSN 2063-8647. JSTOR 26571579.

The name yaqa is the Buriad version of saxa. Its plural form yaqūd is the etymology for the Russian name Yakut.

- ^ ITNR 2018.

- ^ Ivanov 1974, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Ushnitskiy 2016a, p. 150.

- ^ Schukin 1844, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1992, p. 108.

- ^ Kozmin 1928, p. 273.

- ^ Ushnitskiy 2016a, p. 152.

- ^ Radlov 1893, p. 134.

- ^ a b Zoriktuev 2011.

- ^ Rumyantsev 1962, p. 144.

- ^ Ovchinnikov 1897.

- ^ Nimaev 1988, p. 108.

- ^ Karmay 1993, p. 244.

- ^ de Roerich 1999, p. 42.

- ^ Rumyantsev 1962, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Dashieva 2020, pp. 943–944.

- ^ de Roerich 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Zoriktuev 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Lindenau 1983, p. 18.

- ^ Krasheninnikov 1949, p. 406.

- ^ Tokarev 1949.

- ^ Okladnikov 1955.

- ^ Konstantinov 1978.

- ^ Gogolev 1993.

- ^ Ergis 1960, p. 282.

- ^ Ergis 1960, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Gokhman & Tomtosova 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Pavlinskaya 2001, p. 231.

- ^ Stepanov 2005.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Ergis 1960, p. 103.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, p. 120.

- ^ Radlov 1893, p. 191.

- ^ Potapov 1969, p. 182.

- ^ Okladnikov 1955, p. 339.

- ^ Tugolukov 1985, pp. 216, 235.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1977, p. 206.

- ^ Ivanov 2000, p. 19.

- ^ a b Khar'kov et al. 2008.

- ^ Levin & Potapov 1956.

- ^ Antipin 1963.

- ^ Richards 2003, p. 238.

- ^ Levene & Roberts 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Davis, Harrison & Howell 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Lewis 2012.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Kantanen 2012.

- ^ Meerson.

- ^ Andreyevich 2020.

- ^ Russia 2010b.

- ^ a b c d e Fedorova et al. 2013.

- ^ Duggan et al. 2013.

- ^ Adamov 2008, p. 652.

- ^ a b "Sakha families gather in Lynnwood to celebrate ancient summer festival". 25 June 2024.

- ^ "The Sakha Story at Fort Ross". www.fortross.org.

- ^ Kenton Osborn, Sannie. "Death in the daily life of the Ross colony" (PDF). www.fortross.org.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Alekseev, N. A.; Emelyanov, N. V.; Petrov, V. T., eds. (2005). В этом разделе публикуются материалы по книге "Предания, легенды и мифы саха (якутов)" [Traditions, legends and myths of Sakha] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka. pp. 12–16. ISBN 5-02-030901-X. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- Antipin, V. N., ed. (1963). Советская Якутия [Soviet Yakutia]. История Якутской АССР (in Russian). Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Arutyunov, S. A.; Sergeyev, D. A. (1975). Проблемы этнической истории Берингоморья: Эквенский могильник [Problems of the Ethnic History of the Bering Sea: Ekvensky Burial Ground] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Davis, Wade; Harrison, K. David; Howell, Catherine Herbert (2007). Book of Peoples of the World: A Guide to Cultures. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-1-4262-0238-4.

- Dzharylgasinova, R. (1972). Древние когурёсцы (к этнической истории корейцев) [Ancient Koguryeo people (on the ethnic history of the Koreans)] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Ergis, G. U., ed. (1960). Исторические предания и рассказы якутов [Historical legends and stories of the Yakuts] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow; Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Gogolev, A. I. (1993). Проблемы этногенеза и формирования культуры [The Yakuts: Problems of ethnic genesis and cultural formation] (in Russian). Yakutsk: Yakutsk State University.

- Gokhman, I. I.; Tomtosova, L. F. (1992). "Антропологические исследования неолитических могильников Диринг-Юрях и Родинка" [Anthropological researches of the Neolithic burial grounds of Diring-Yuryakh and Rodinka]. Археологические исследования в Якутии: Сб. трудов Приленской археол. экспедиции [TEST] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka. pp. 105–124.

- Ivanov, V. F. (1974). Историко-этнографическое изучение Якутии XVII–XVIII вв [Historical and ethnographic study of Yakutia of the 17th and 18th centuries] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Kochnev, D. A. (1899). "Очерки юридического быта якутов" [Essays on the legal life of the Yakuts]. Proceedings of the Society of Archeology, History, Ethnography at the Imperial Kazan University. 15 (2). Imperial Kazan University.

- Konstantinov, I. V. (1978). Ранний железный век Якутии [Early Iron Age in Yakutia] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kozmin, Nikolai Nikolaevich (1928), К вопросу о происхождении якутов-сахалар [On the origin of the Yakut-sakhalar] (in Russian), Irkutsk

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Krasheninnikov, S. P.. (1949). Описание Земли Камчатки [Description of the Land of Kamchatka] (in Russian). Moscow, Leningrad: Glavsevmorput. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Ksenofontov, G. V. (1977). Эллэйада: Материалы по мифологии и легендарной истории якутов [Elleiada (fables about Ellei): Materials on Yakuts' mythology and legendary history] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Ksenofontov, G. V. (1992). Ураанхай сахалар: Очерки по древней истории якутов [Uraankhay-sakhalar: Essays on the ancient history of the Yakuts] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Yakutsk: Бичик.

- Levene, Mark; Roberts, Penny (1999). The Massacre of History. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-934-5.

- Lindenau, Jacob Johan (1983). Описание народов Сибири (первая половина XVIII века): Историко-этнографические материалы о народах Сибири и Северо-Востока [Description of the Peoples of Siberia (First Half of the Eighteenth Century): Historical and Ethnographical Materials on the Peoples of Siberia and North-East]. Дальневосточная историческая библиотека (in Russian). Translated by Titova, Z. D. Magadan: Magadan.

- Levin, M. G.; Potapov, L. P., eds. (1956). Народы Сибири [Peoples of Siberia] (in Russian). Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Nimaev, D. D. (1988). Проблемы этногенеза бурят [Problems of the ethnogenesis of the Buryats] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Okladnikov, A. P. (1955). Якутия до присоединения к русскому государству [Yakutia before joining Russia] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow, Leningrad: yes.

- Okladnikov, Alexey Pavlovich (1970). Michael, Henry N. (ed.). Yakutia: Before its incorporation into the Russian State. Anthropology of the North: Translations from Russian Sources. Montreal & London: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9068-7.

- Ovchinnikov, Mikhail Pavlovich (1897). Из материалов по этнографии якутов [From the materials on the ethnography of the Yakuts]. Этнографическое обозрение (in Russian).

- Pavlinskaya, L. R. (2001). Некоторые аспекты культурогенеза народов Сибири (по материалам шаманского костюма) [Some aspects of the cultural genesis of Siberian peoples (materials of shaman's costume)] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Евразия сквозь века. pp. 229–232.

- Popov, Gavriil V. (1986). Слова "неизвестного происхождения" якутского языка (сравнительно-историческое исследование) [Words of "unknown origin" of the Yakut language (comparative historical study)] (in Russian). Yakutsk: Yakut Book Publishing House.

- Potapov, L. P. (1969). Этнический состав и происхождение алтайцев: Историко-этнографический [Ethnic structure and origin of Altai people: A historical and ethnographic essay] (in Russian). Leningrad: Nauka.

- Radlov, Vasily Vasilievich (1893). Aus Sibirien: Lose Blätter aus meinem Tagebuche [From Siberia: Loose Leaves from my Diary] (in German). Leipzig: T. O. Weigel Nachfolger.

- Richards, John F. (2003). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-93935-2.

- de Roerich, George (1999). test [Tibet and Central Asia: Articles, Lectures, Translations] (in Russian). Samara: Publishing House Agni.

- Rumyantsev, G. N. (1962). Происхождение хоринских бурят [Origin of the Khori Buryats] (in Russian). Ulan-Ude: Buryat Book Publishing House.

- Schukin, Nikolai Semyonovich (1844). Поездка в Якутск [A Trip to Yakutsk] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). St. Petersburg: Типография Временного Департамента Военных Поселений.

- Stepanov, A. D. (2005). Самодийская и юкагирская топонимика на карте Якутии: К проблемам генезиса древ-них культур Севера [Samoyedic and Yukaghir toponymics on the map of Yakutia: genesis of ancient cultures of the North revisited]. Социогенез в Северной Азии (in Russian). Irkutsk: Издательство ИРНИТУ. pp. 223–227.

- Tugolukov, V. A. (1985). Тунгусы (эвенки и эвены) Средней и Западной Сибири [Tungusic people (Evenkis and Evens) of Central and Western Siberia] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

Articles

[edit]- Adamov, D. (2008). "Расчет возраста популяции якутов, принадлежащих к гаплогруппе N1c1" [Calculation of age for Yakut population belonging to haplogroup N1c1] (PDF). Proceedings of the Russian Academy of DNA Genealogy (in Russian). 1 (4): 646–656. ISSN 1942-7484. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2015.

- Bravina, R. I.; Petrov, D.M. (2018). "Tribes «Which Became Wind»: Autochthonous Substrate in Ethnocultural Genesis of the Yakuts Revisited" (PDF). Vestnik Arheologii, Antropologii I Etnografii (in Russian). 2 (41). Institute for Humanities Research and Indigenous Studies of the North: 119–127. doi:10.20874/2071-0437-2018-41-2-119-127.

- Dashieva, Nadezhda B. (25 December 2020). "Образ оленя-солнца и этноним бурятского племени Хори" [Image of the Deer-Sun and Ethnonym of the Khori Buryats]. Oriental Studies (in Russian). 13 (4). East Siberian State Institute of Culture: 941–950. doi:10.22162/2619-0990-2020-50-4-941-950. S2CID 243027767. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Duggan, Ana T.; et al. (12 December 2013). "Investigating the Prehistory of Tungusic Peoples of Siberia and the Amur-Ussuri Region with Complete mtDNA Genome Sequences and Y-chromosomal Markers". PLOS ONE. 8 (12) e83570. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...883570D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083570. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3861515. PMID 24349531.

- Fedorova, Sardana A.; et al. (19 June 2013). "Autosomal and uniparental portraits of the native populations of Sakha (Yakutia): implications for the peopling of Northeast Eurasia". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 127. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13..127F. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-127. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3695835. PMID 23782551.

- Ivanov, M. S. (2000). "Замыслившие побег в Пегую орду...: (О топониме Яркан-Жархан)" [Those who planned to flee to the Skewbald Horde…: (About the toponym Zharhan)]. Илин (in Russian) (1): 17–20.

- Karmay, Samten G. (1993). "The theoretical basis of the Tibetan epic, with reference to a 'chronological order' of the various episodes in the Gesar epic". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 56 (2): 234–246. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00005498. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162562519.

- Khar'kov, V. N.; et al. (2008). "[The origin of Yakuts: analysis of Y-chromosome haplotypes]". Molekuliarnaia Biologiia. 42 (2): 226–237. ISSN 0026-8984. PMID 18610830.

- Petri, B. E. (1922). "М.П. Овчинников как археолог" [M.P. Ovchinnikov as an archaeologist]. Сибирские огни (4).

- Petri, B. E. (1923). "Доисторические кузнецы в Прибайкалье. К вопросу о доисторическом прошлом якутов" [Prehistoric blacksmiths in the Baikal region. On the prehistoric past of the Yakuts.]. Известия Института народного образования. 1. Chita: 62–64.

- Strelov, E. D. (1936). "Одежда и украшения якутки в половине XVIII в. (по археологическим материалам)" [Clothing and jewelry of the Yakut in the middle of the 18th century. (based on archaeological materials)]. Soviet Ethnography. 2–3: 75–99. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Tokarev, S. A. (1949). "К постановке проблем этногенеза" [Problems of ethnic genesis revisited]. Советская Этнография (3): 12–36.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy V. (2016a). "Researchers of Tsarist Russia on the study of the origin of the Sakha people". Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta (in Russian) (407). Yakutsk: Institute of the Humanities and the Indigenous Peoples: 150–155. doi:10.17223/15617793/407/23.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy. V. (2016b). "The Problem of the Sakha People's Ethnogenesis: A New Approach". Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences. 8: 1822–1840. doi:10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-8-1822-1840.

- Zoriktuev, B. R. (2011). "Who are the Yakut Khorolors? (a contribution to the issue of ethnic identification)". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 39 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2011.08.012.

Census information

[edit]- data.europa.eu (in Latvian), data.europa.eu, 2021, retrieved 4 January 2022

- Kazakhstan (2009a). "Kazakhstan in 2009" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Kazakhstan (2009b). "Official website of the 2009 Kazakh census" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Kazakhstan (2009c). "Nationality composition of population" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Latvia (2021). "Latvia population estimate" (PDF) (in Latvian). Office of Citizenship and Immigration Affairs. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Russia (2010a). "Official website of the 2010 Russian census" (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Russia (2010b). "Languages spoken … by subjects of the Russian Federation" (PDF) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Ukraine (2001). "Official website of the 2001 Ukrainian census" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

Websites

[edit]- Andreyevich, Murzin Y. (2020). "Kigilyakhi of Yakutia" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Kantanen, Juha (2012). "The Yakutian cattle: A cow of the permafrost" (PDF). pp. 3–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Lewis, Martin (14 May 2012). "The Yakut Under Soviet Rule". GeoCurrents. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Meerson, F. "Survival". UNESCO. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Yakuts", Inside the New Russia, 2018, retrieved 4 January 2022

Further reading

[edit]- Conolly, Violet. "The Yakuts," Problems of Communism, vol. 16, no. 5 (Sept.-Oct. 1967), pp. 81–91.

- Tomskaya, Maria. 2018. "Verbalization of Nomadic Culture in Yakut Fairytales". In: Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 9 (2): 253–62. Verbalization of Nomadic Culture in Yakut Fairytales.

- Tomskaya, Maria. 2020. "Fairy Tale Images As a Component of Cultural Programming: Gender Aspect" [Сказочные образы как составляющая культурного программирования: гендерный аспект]. In: Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 11 (2): 145–53. Fairy tale images as a component of cultural programming: gender aspect: Сказочные образы как составляющая культурного программирования: гендерный аспект.

Yakuts

View on GrokipediaNomenclature

Etymology of "Yakut"

The exonym "Yakut" originates from the Evenk (Tungusic) word yako or yakoł, denoting "stranger" or "outsider," a term used by neighboring Evenk groups to refer to the Sakha during early interactions in Siberia.[7][8] This linguistic borrowing reflects the Sakha's relatively recent migration into the Lena River basin, where they encountered indigenous Tungusic populations, distinguishing them as newcomers distinct from local hunter-gatherers and reindeer herders.[9] Russian explorers adopted the Evenk-derived term in the early 17th century, with initial documented uses appearing in records of Cossack detachments that reached the Lena River region around 1632–1633, during expeditions led by figures like Pyotr Beketov to establish forts and collect fur tribute (yasak).[10] These accounts, tied to the broader Russian conquest of Siberia, marked the first external application of "Yakut" to the Sakha clans encountered along trade routes, supplanting any prior local designations in official correspondence.[11] Following the consolidation of Russian control in the mid-17th century, the term "Yakut" standardized in imperial documentation, appearing consistently in administrative registers and population tallies by the 18th century, such as those tracking tribute obligations and settlement patterns in the newly formed Siberian governorates.[12] This shift entrenched the exonym in bureaucratic usage, despite the Sakha's own ethnonym, underscoring the influence of intermediary Tungusic nomenclature on Russian perceptions of the group.[7]Self-Designation as Sakha

The Sakha, a Turkic-speaking people indigenous to northeastern Siberia, employ the endonym Sakha to denote their ethnic group, distinguishing it from the Russian exonym "Yakut," which derives from Evenk terminology for "stranger" or "other."[7] This self-designation traces to Proto-Turkic jaka, connoting "edge" or "collar," potentially evoking the collars used in their traditional horse and cattle herding, central to Sakha pastoral economy and cultural identity.[13] Earliest linguistic attestations appear in the oral epic tradition of Olonkho, UNESCO-recognized as embodying Sakha cosmology, origins, and social norms, where the term reinforces collective self-perception as resilient migrants adapted to taiga and tundra environments through livestock management.[14][15] Following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Soviet ethnographic frameworks began integrating Sakha alongside "Yakut" to classify the group within nationality policies, acknowledging its Turkic linguistic affiliations despite geographic isolation from core Turkic ranges.[16] This dual nomenclature persisted until the late Soviet era, when the autonomous oblast was redesignated the Yakut-Sakha Soviet Socialist Republic on September 27, 1990, via a sovereignty declaration emphasizing indigenous terminology.[17] The post-Soviet transition amplified Sakha's primacy: on December 27, 1991, the entity became the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), with the 1992 constitution mandating the endonym in official documents and republican insignia, symbolizing ethnic agency in nomenclature amid federal asymmetries.[18][19] This shift highlights a deliberate reclamation, prioritizing empirical ties to Turkic heritage over imposed labels, while navigating Russia's multiethnic governance.[2]Geographic and Demographic Overview

Primary Settlement in Sakha Republic

The Yakuts maintain their primary settlement within the Sakha Republic, a vast territory spanning 3,083,523 square kilometers of predominantly subarctic landscapes, including expansive taiga forests dominated by larch in the north and transitioning to tundra in the higher latitudes.[20][21] The core of this settlement aligns with the Lena River basin, which drains much of the republic and facilitates seasonal mobility across riverine lowlands and adjacent uplands, shaping historical patterns of habitation tied to riparian resources and floodplains.[22] Yakutsk serves as the longstanding administrative hub, established as a fort in 1632 along the Lena River's right bank, anchoring centralized settlement amid the republic's dispersed geography.[23] Environmental extremes, such as the severe winters in the Oymyakon region—where temperatures reached -67.7°C in 1933—have causally driven adaptive strategies, including historical semi-nomadism to exploit varying seasonal forage in taiga clearings and tundra margins.[24] Permafrost underlies 90-100% of the Sakha Republic's land area, enforcing constraints on permanent structures and mobility routes, with ongoing thaw dynamics as of 2025 exacerbating isolation in this resource-abundant yet logistically challenging expanse.[25] This frozen substrate, coupled with the basin's meandering hydrology, underscores the interplay between terrain and settlement persistence, favoring valley concentrations over upland expanses.Population Estimates and Trends

According to estimates derived from the 2021 Russian census, the ethnic Yakut (Sakha) population numbers approximately 478,000 individuals, nearly all residing within the Sakha Republic.[26] This group constitutes about 48% of the republic's total population of 995,686 as of that census year.[27] The absolute Yakut population has remained relatively stable since the 2010 census figure of 466,492, reflecting low overall growth amid broader Russian demographic contraction.[19] Demographic trends indicate a gradual erosion of the Yakut share within the Sakha Republic, attributable to historical Russification policies that encouraged Russian in-migration and cultural assimilation, alongside accelerating urbanization.[2] Urban centers like Yakutsk have expanded rapidly, with the city population rising from 186,000 in 1989 to over 338,000 by 2018, drawing Yakuts from rural areas and exposing them to interethnic mixing that dilutes ethnic identification over generations.[19] Rural Yakut communities, which retain higher concentrations of traditional lifestyles, face aging populations and depopulation, as younger cohorts migrate to cities for economic opportunities, straining local social services and exacerbating infrastructure decay in remote uluses.[28] Fertility rates among Yakuts have historically exceeded the national Russian average, with mean completed fertility for Yakut women reported at levels above those in ethnic Russian populations (typically 3.99–6.99 children per woman in comparative studies), supporting population maintenance into the early 2000s.[29] However, Sakha Republic rates have converged toward Russia's sub-replacement levels (around 1.5 births per woman nationally in recent years), influenced by economic pressures and delayed childbearing in urbanizing families.[30] Recent trends include net out-migration, particularly from 2022 to 2025, as thousands of Yakuts relocated to Kazakhstan amid fears of military mobilization related to the Ukraine conflict, economic sanctions-induced hardships, and perceived ethnic discrimination within Russia.[31] This exodus, concentrated among younger professionals, has accelerated rural decline and prompted community formation in Kazakh cities like Almaty, where Sakha migrants leverage linguistic and cultural affinities with Turkic Kazakhs for integration.[32]Urbanization and Rural Persistence

Approximately 67% of Sakha Republic's population resided in urban areas as of 2024, with the capital Yakutsk accounting for over 340,000 inhabitants and serving as the primary hub for administrative, educational, and economic activities.[33][34] This urbanization trend accelerated during the Soviet period through state-directed industrialization, particularly in diamond, gold, and tin mining, which concentrated jobs and infrastructure in Yakutsk and secondary centers like Mirny and Neryungri, drawing migrants from rural districts amid collectivization and resource extraction drives starting in the 1920s for gold and 1960s for diamonds.[35][36] High logistics costs in the vast, permafrost-dominated territory—exacerbated by limited road networks and reliance on seasonal river transport—further incentivized urban agglomeration for access to reliable energy, supply chains, and services. The remaining 33% of the population persists in rural naslegs, traditional clan-based administrative units comprising over 590 localities where agropastoralism centered on horse and cattle breeding sustains livelihoods despite climatic extremes.[4][37] Post-1991 land reforms, including privatization decrees and the Far Eastern Hectare program, enabled leasing and eventual ownership of plots for household farming, bolstering communal tenure systems and slowing full integration into wage labor markets by preserving subsistence-oriented economies tied to ancestral grazing lands.[38][39] These rural communities face acute challenges, including poverty incidence roughly 2.7 times the republic's average—reaching 55% substandard income in households—and heightened vulnerability to infrastructural failures, as evidenced by the 2025 heating season shortfalls where budget constraints and aging boilers led to supply drops of up to 8.4% below prior peaks amid subzero temperatures.[40][41] Economic drivers like mining's urban pull contrast with rural reliance on local resources, where permafrost thaw and isolation amplify costs for fuel and feed, yet cultural attachments to nasleg governance and pastoral practices resist proletarianization, maintaining demographic stability in peripheral districts.[42][19]Origins and Ancestry

Archaeological Correlates

The archaeological record in the Lena Valley documents human presence from the Paleolithic era onward, but correlates with Yakut (Sakha) ethnogenesis primarily emerge in the medieval period, consistent with migration from southern regions rather than long-term indigenous continuity. Earlier horizons, such as the Ymyyakhtakh culture (ca. 2200–1300 BCE), feature distinctive comb-marked pottery, slate tools, and burial practices across a broad Siberian expanse originating in the Lena basin, yet these reflect Late Neolithic adaptations by pre-Turkic populations without evidence of horse domestication or advanced pastoralism characteristic of later Yakut economies.[43][44] Bronze metallurgy spread to Yakutia by the late first millennium BCE, evidenced by production sites and artifacts along the Lena River, signaling technological influxes potentially tied to broader Eurasian networks but predating distinct Yakut cultural markers. Iron smelting sites attributed to Sakha groups, such as those in the Khemkonsky district, demonstrate local adaptation of metalworking for tools and weapons, aligning with pastoral needs introduced via migration. Horse remains in medieval contexts, including harness fittings and sacrificial deposits, indicate integration of steppe-derived equestrian traditions, absent in pre-13th-century assemblages and supporting influx from Baikal-area precursors around the 13th–15th centuries CE.[45][46][47] Tumat-related sites, referenced in Sakha oral traditions as early Turkic kin groups, yield artifacts suggestive of southward-oriented trade, including metal imports and fishing implements, with radiocarbon assays from associated strata yielding dates circa 1000 CE; these challenge claims of pure autochthonous development by evidencing external contacts and cultural discontinuities. Overall, the paucity of Turkic-specific pastoral artifacts—such as widespread horse gear or clan-based fortifications—prior to the 13th century underscores a migration-driven ethnogenesis from Baikal latitudes, overlaying rather than evolving from local Neolithic substrates.[8][48]Linguistic Affiliations and Migrations

The Sakha language, spoken by the Yakuts, belongs to the northeastern branch of the Turkic language family, exhibiting significant divergence from other Turkic varieties due to early separation from the common Turkic linguistic continuum around the first half of the first millennium CE.[49][50] This separation is marked by retention of archaic Proto-Turkic features, including vowel harmony—where vowels within a word must agree in tongue root position (front or back)—and the distinction between instrumental and comitative cases, which have been lost or merged in many southern and western Turkic languages.[50] At the same time, Sakha displays innovations in lexicon tailored to subarctic conditions, such as derivations and adaptations for phenomena like prolonged winter darkness and frozen terrain, often building on Turkic roots but extended through contact-induced shifts.[51] Comparative philology traces the northward migrations of Sakha speakers from the Lake Baikal region to the Lena River basin between the 13th and 15th centuries CE, a period of upheaval following the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire.[52] This trajectory is evidenced by the incorporation of Mongolic loanwords—estimated at over 10% of core vocabulary, including terms for administrative and pastoral concepts—reflecting prolonged interaction in the pre-migration steppe zones, alongside Tungusic (Evenki) borrowings for hunting tools, reindeer-related nomenclature, and environmental terms acquired during the push into Tungusic territories.[50][51] These substratal influences underscore a pattern of linguistic adaptation amid demographic displacements, with post-Mongol pressures driving small groups into sparsely populated northern expanses. Dialectal variation in Sakha reveals founder effects from these bottleneck migrations, characterized by low overall diversity and retention of uniform phonological and morphological traits across expansive regions, consistent with expansion from limited progenitor populations.[50] Subtle isoglosses in vocabulary and phonetics correlate with the territorial domains of major clans (known as us in Sakha), whose expansions and subdivisions were documented in 17th-century Russian ethnographies, such as those compiled during the establishment of Yakutsk fort in 1632, linking linguistic micro-variations to patrilineal group dispersals rather than continuous diffusion.[53] This clan-dialect alignment highlights how migratory founder events preserved linguistic homogeneity while permitting localized lexical divergences tied to resource exploitation and inter-clan alliances.[54]Genetic Evidence and Population Dynamics

Genetic analyses of the Yakut (Sakha) population indicate a pronounced founder effect in Y-chromosome lineages, dominated by haplogroup N1c, which constitutes over 90% of paternal haplotypes in many subgroups.[55] This signature, characterized by reduced STR diversity and a star-like phylogenetic network, dates to approximately 880 years before present, pointing to a bottleneck during a male-biased migration from southern Siberia rather than local continuity.[56][48] Mitochondrial DNA profiles reveal predominantly East Asian haplogroups, including C (around 40-50%) and D (20-30%), with lesser contributions from A, B, F, G, and Z, alongside a minor West Eurasian fraction (under 10%, e.g., H, J, T).[48][57] This maternal diversity suggests dual origins, with post-migration admixture primarily involving Tungusic groups like Evenks, likely through unions between incoming Yakut males and local females, rather than isolation around Lake Baikal.[58] Autosomal SNP data align Yakuts more closely with South Siberian populations than with Central Asian Turkic groups, showing limited genetic input from Altaic or Mongolian sources despite linguistic ties, which challenges earlier assumptions of direct westward Turkic expansion.[55][56] Epigenetic profiling via whole-blood DNA methylation identifies Yakut-specific patterns, including hypermethylation at sites linked to cold stress response genes (e.g., those regulating thermogenesis and inflammation), facilitating physiological adaptations to subarctic conditions without evidence of pre-migration autochthonous markers.[59] These dynamics reflect rapid demographic expansion from a small founding cohort, with ongoing gene flow from neighboring indigenous Siberians shaping contemporary structure.[48]Historical Trajectory

Pre-Russian Migrations and Societies

The Sakha (Yakuts) undertook northward migrations from the Enisei River region and areas near Lake Baikal to the Lena River basin primarily between the 13th and 15th centuries, prompted by the political instability and conflicts arising from the Mongol Empire's campaigns and subsequent fragmentation after the death of Ögedei Khan in 1241.[60] These movements involved Turkic-speaking pastoralists who brought horse husbandry, enabling semi-nomadic lifestyles adapted to subarctic conditions, with groups advancing along river valleys over several generations.[61] Upon settling, they displaced or marginalized indigenous populations, establishing dominance through clan-based organization centered on khoro—exogamous patrilineal descent groups tracing origins to eponymous ancestors like Ulugun Khoro.[8] Sakha societies formed decentralized tribal confederations, comprising multiple khoro allied under influential chieftains who coordinated seasonal migrations, defense, and resource allocation among herds of horses, cattle, and reindeer.[54] By the early 17th century, these structures featured prominent lineages such as the Tygyn clan, which exerted regional influence through martial prowess and control over fertile floodplains, as evidenced in oral traditions preserving accounts of inter-clan alliances and rivalries.[54] Epic narratives in the Olonkho tradition, such as those featuring heroes like Elley, encapsulate these dynamics, portraying archetypal chieftains who embody real historical figures leading confederations against external threats or internal disputes.[62] Interactions with neighboring Evenks (Tungusic speakers) and Yukaghirs (Paleo-Siberian speakers) were marked by competition for hunting grounds and grazing lands in the Lena basin, where Sakha groups achieved numerical and organizational superiority by the 15th century, assimilating some local elements while imposing their Turkic linguistic framework.[48] Linguistic evidence shows Sakha borrowing terms for local fauna and taiga-specific technologies from Evenks and Yukaghirs, yet maintaining dominance through fortified winter settlements (*khatyng) and cavalry tactics ill-suited to indigenous reindeer herders.[50] This hegemony consolidated Sakha control over the middle Lena by the late 16th century, fostering a stratified society with princes (toyons) overseeing tribute from subordinate clans and hunters.[50]Russian Expansion and Subjugation

In the early 1630s, Russian Cossack detachments from the Yeniseysk voivodeship advanced eastward into the Lena River basin, encountering Yakut pastoralist clans dispersed across the taiga and floodplains. These expeditions, driven by the pursuit of fur riches, culminated in 1632 when sotnik Pyotr Beketov established the Yakutsk ostrog as a fortified base for administrative control and tribute collection.[63][64] Beketov's forces, numbering in the low hundreds, imposed the iasak system, requiring Yakut toyons (clan heads) to deliver sable, fox, and other pelts annually to Russian officials, often under threat of reprisal for non-compliance.[64] Initial collections targeted approximately 35 clans, exploiting existing inter-clan rivalries to secure compliance from some leaders while coercing others through raids.[65] Yakut responses included organized uprisings throughout the 1630s and 1640s, as clans mobilized thousands of horsemen armed with bows, spears, and lances to ambush Cossack parties and besiege ostrogs. Notable revolts occurred in 1633–1634, 1636–1637, 1639–1640, and a large-scale clan coalition in 1642, which temporarily expelled Russian detachments from peripheral territories.[66] Russian forces countered with punitive campaigns involving massacres of villages, enslavement of captives for labor or ransom, and scorched-earth tactics that depleted Yakut herds and populations in contested districts.[54] Superior firepower—muskets and cannons—along with tactical alliances with rival Yakut factions enabled Cossacks to crush these resistances, as documented in contemporary service records emphasizing decisive victories despite Yakut numerical advantages.[67] By the 1680s, outright annihilation gave way to a stabilized tribute economy, with ostrogs like Yakutsk serving as sedentary hubs for oversight rather than mere conquest outposts. Selective partnerships with cooperative toyons, who received exemptions or trade privileges, facilitated annual iasak deliveries exceeding 10,000 sables by mid-century, integrating Yakut society into Russian fiscal networks without full-scale depopulation.[68] This pragmatic shift reflected causal realities of sparse Russian manpower—rarely exceeding 1,000 troops in Yakutia—and the economic imperative of sustaining fur yields over endless warfare.[54]Imperial Governance and Resistance

In 1805, as part of administrative reforms under Tsar Alexander I, the Yakutsk Oblast was detached from Irkutsk Governorate, forming a dedicated territorial unit for governing the expansive Siberian frontier, including Yakut (Sakha) clans under voevoda oversight and tribute obligations.[69] This structure facilitated centralized tax collection, primarily the yasak fur tribute, while enabling trade networks that supplied Yakuts with Russian goods like flour, tobacco, and metal implements, contributing to demographic stabilization after earlier conquest-era depopulations.[67] Imperial censuses, such as the 1897 all-Russian enumeration, recorded Yakutsk okrug's population at approximately 238,000, with Yakuts comprising over 60%, reflecting recovery through intermarriage, migration, and economic incentives like horse breeding for Russian markets, though tribute demands strained nomadic pastoralism.[70] Resistances persisted, including localized uprisings in the 1810s against escalated iasak quotas and arbitrary voevoda exactions, where clans withheld furs or raided outposts, prompting punitive Cossack expeditions that reinforced subjugation without eradicating autonomy in internal clan affairs.[69] Russian settlers introduced ironworking enhancements, such as forge techniques and plows, yielding economic gains in tool durability and agricultural yields for sedentary Yakut subgroups by the mid-19th century, alongside Orthodox literacy programs that reached select elites.[71] The 1825 Decembrist exiles, numbering several dozen dispatched to Yakutsk settlements, further influenced this milieu; figures like Nikolai Bestuzhev engaged locals through tutoring in sciences and languages, seeding bilingualism and proto-intelligentsia networks that preserved Yakut oral traditions amid selective Russification.[69] These interactions fostered pragmatic adaptation—evident in 1860s petitions for tax relief tied to cultural concessions—without wholesale assimilation, as clan-based resistance to land seizures underscored ongoing tensions.[72]Soviet Transformation and Collectivization

The Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) was established on April 27, 1922, as part of the Russian SFSR, providing the Yakut population with formal autonomy amid the consolidation of Bolshevik power following the Russian Civil War. This status included provisions for local governance and cultural institutions, though central control limited genuine self-determination, with Moscow directing key economic and political decisions from the outset.[73][74] Collectivization drives in the early 1930s dismantled traditional pastoral economies, compelling semi-nomadic herders—primarily engaged in reindeer husbandry and cattle rearing—to join state farms (kolkhozy), which prioritized grain production and sedentarization over mobility. This shift eroded customary land use and migration patterns, fostering dependence on fixed settlements and mechanized agriculture ill-suited to the subarctic taiga, while resistance led to confiscations and deportations. Accompanying these reforms were the Stalinist purges of 1936–1938, which systematically targeted Yakut party officials, intellectuals, and clan leaders as "nationalist deviants" or "kulaks," resulting in executions, imprisonments, and the liquidation of much of the nascent indigenous elite to enforce ideological conformity.[72][75] Forced labor from the Gulag system, particularly in the Kolyma region under Yakut ASSR administration until the late 1930s, fueled infrastructure projects like roads, mines, and ports, extracting gold and timber that supported wartime industry after 1941 evacuations relocated some western Soviet factories eastward. These efforts, combined with universal compulsory education campaigns, elevated literacy rates across the ASSR to near universality by the late 1950s, reflecting broader Soviet achievements in eradicating illiteracy through state schools teaching in Yakut and Russian.[76][77] Sovietization campaigns suppressed shamanistic practices, branding shamans as counter-revolutionary elements and confiscating ritual objects, which marginalized indigenous spiritual systems in favor of atheistic materialism. However, state-sponsored academies documented and adapted Yakut epics like Olonkho for ideological purposes, preserving oral traditions in written form under ethnographic oversight while purging "feudal" elements. Collectivization-induced hardships, including localized famines from disrupted food systems, claimed lives in the thousands during the 1930s but coincided with post-purges demographic recovery through natural increase and Russification policies.[78]Post-1991 Autonomy and Resource Exploitation

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic transitioned to the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), acquiring enhanced political autonomy as a federal subject of Russia while retaining substantial control over its resource extraction sectors.[19] This status enabled Sakha to leverage its diamond mines, operated primarily by Alrosa, which produced 33 million carats in 2024—accounting for over 90% of Russia's total diamond output, nearly all extracted from Sakha territory.[79][80] Diamond-related extraction taxes have formed a cornerstone of the republican budget, with Sakha receiving 82.4% of Russia's national diamond tax revenues in 2020, underscoring resource dependency amid federal revenue-sharing dynamics.[81] Resource wealth has not quelled underlying frictions, as evidenced by the emergence of independence advocacy groups like the "Resistance" movement in August 2023, which seeks Sakha's secession and repatriation of resource control to local citizens.[2] The 2022 partial mobilization for Russia's Ukraine operation intensified resistance in Sakha, marked by protests, recruitment shortfalls averaging 40% of federal quotas into 2025, and documented violations of indigenous rights during conscription drives.[82][83] Federal anti-poverty initiatives under President Putin, including a multi-year program launched around 2024 to halve Sakha's 15% poverty rate—prioritizing large families—aim to mitigate socioeconomic disparities tied to extractive economies.[84] Infrastructure vulnerabilities persist, with heating system collapses in Sakha during subzero winters—such as those reported in early 2025—exposing aging networks and geographic isolation, often leaving thousands without heat amid broader Far East utility failures.[85] Mining expansion has precipitated land-use conflicts, as emissions, waste, and permafrost degradation from extractives have damaged pastures and arable areas essential to rural herding, with studies noting ecosystem losses along development corridors like the Northern Sea Route.[86][87] Despite these environmental costs, resource exports have elevated Sakha's gross regional product per capita above the national average, though gains remain concentrated and federal transfers critical for redistribution.[67]Language and Linguistics

Turkic Roots and Divergences

The Sakha language, spoken by the Yakuts, is classified within the Northeastern branch of the Turkic language family, also known as Siberian Turkic, distinguishing it from Oghuz, Kipchak, and Karluk branches.[51] This affiliation is supported by shared core vocabulary, such as basic kinship terms and numerals, traceable to Proto-Turkic roots reconstructed around the 1st millennium CE in the Central Asian steppes.[50] Sakha's position reflects a migration of Turkic-speaking groups northward into Siberia, likely between the 13th and 15th centuries, as evidenced by linguistic retentions like the preservation of initial *p- sounds (e.g., *päj "summer" > Sakha *bäjï), which were lost in southern Turkic varieties through lenition.[53] Sakha is most closely related to Dolgan, a language spoken by a small Evenk-Yakut group in northern Siberia, with Dolgan emerging as a distinct variety from Sakha dialects around the 17th–18th centuries through contact-induced divergence among reindeer-herding communities.[88] This split involved partial retention of Sakha features alongside innovations, such as increased Evenki lexical borrowing in Dolgan for pastoral terms, underscoring a shared substrate from Tungusic languages like Evenki during the Yakuts' adaptation to subarctic environments.[50] Evenki influence on Sakha includes substrate effects in phonology and lexicon, with loans comprising a notable portion of terms for local flora, fauna, and hunting practices, reflecting pre-migration bilingualism among proto-Yakut groups displacing or assimilating Tungusic speakers.[53] Like other Turkic languages, Sakha employs agglutinative morphology, where suffixes accumulate linearly to indicate grammatical relations, as in verb forms like *täb-ïr "I sit" deriving from root *täb- plus person markers.[89] Vowel harmony remains a core feature, operating progressively to match front/back and rounded/unrounded qualities across syllables (e.g., *kïïh "winter" with back harmony), though exceptions arise in loanwords and certain suffixes due to Siberian isolations.[90] Divergences include the loss of certain Proto-Turkic distinctions, such as simplified case systems adapted to isolate speech communities, and phonological shifts like the merger of some diphthongs, which mark Sakha's evolution apart from steppe Turkic norms.[50] These developments result in low mutual intelligibility with distantly related Turkic languages, such as those in the Anatolian branch (e.g., Turkish), where shared cognates like *ata "father" exist but syntactic and phonological divergences—exacerbated by Sakha's fricative-heavy inventory and Evenki adstrata—render comprehension near zero without study.[91] This isolation highlights Sakha's adaptations to Siberian ecology, prioritizing substrate integrations over pan-Turkic convergence, as confirmed by comparative reconstructions showing greater lexical divergence (up to 50–60% non-cognate basic vocabulary) from western branches than from neighboring Dolgan.[92]Phonetic and Grammatical Features

The Sakha language exhibits a rich phonological system with over 20 consonant phonemes, including uvular stops (/q/, /ɢ/) and fricatives (/ʁ/, /χ/), which distinguish it from many other Turkic languages through retention of these back articulations derived from Proto-Turkic.[90] Palatalization is prominent, featuring sounds like the voiced palatal nasal /ɲ/, unique among most Turkic varieties alongside Khorasani Turkic, and affecting consonants in specific environments to signal vowel harmony influences.[93] The vowel inventory comprises eight short and eight long phonemes, contrasting in height, backness, and rounding, with vowel length playing a phonemic role as evidenced in minimal pairs where duration alters meaning.[94] [95] Grammatically, Sakha is agglutinative with no grammatical gender, relying instead on case marking for nouns, which inflect in at least seven cases including nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, locative, and prolative to encode spatial, possessive, and relational functions.[90] Verbs emphasize aspect over tense, with dominant categories such as imperfective, perfective, and habitual forms constructed via suffixes that prioritize event completion or iteration, often combined with modal elements for nuanced temporal expression.[90] Evidentiality is conveyed through syntactic constructions, such as polypredicative structures with auxiliaries like -bara 'say' for hearsay or reported information, allowing speakers to indicate the reliability or source of knowledge without dedicated inflectional morphemes.[96] Russian contact has introduced loanwords and occasional hybrid forms, particularly in colloquial registers, yet the core phonological contrasts and grammatical agglutination remain intact, preserving Turkic structural integrity amid bilingualism.[90]Orthography Evolution and Usage

Prior to the 20th century, Sakha orthography was rudimentary and confined primarily to elite or missionary contexts, with early attempts including an ideographic system developed by Otto Boethlingk in 1851 using modified Cyrillic characters to approximate Sakha phonemes, and sporadic use of rune-inspired scripts like Ol'khon for religious texts, though these remained non-standardized and inaccessible to the broader population.[97][98] In the Soviet era, initial literacy campaigns led to the adoption of a Latin-based alphabet in 1917 by Semyon Novgorodov, drawing from the International Phonetic Alphabet, which underwent refinements until 1929 before a unified Latin script was trialed through the 1930s; however, by 1939–1940, it was replaced with a Cyrillic-based system to align with broader Russification policies, incorporating four additional letters—ҕ (for /ɣ/), ҥ (for /ŋ/), ө (for /ø/), and һ (for /h/)—to faithfully represent Sakha's distinct uvular, velar, and front rounded vowel phonemes absent in standard Russian Cyrillic.[49][97] This orthography enhanced phonetic accuracy, enabling precise documentation of oral traditions such as the Olonkho epic, whose transcription efforts from the mid-20th century onward supported its UNESCO recognition as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2005 and served as a bulwark against linguistic assimilation.[62][98] Contemporary usage reflects bilingual pressures, with Sakha Cyrillic employed in education, media, and literature for roughly 450,000 speakers per 2010 census data, though proficiency has declined among youth due to Russian dominance in urban settings and schooling, as evidenced by reported drops in workplace usage and generational shifts toward code-mixing.[49][99] Post-2000 digital initiatives, including font standardization and online keyboards, have bolstered orthographic consistency in virtual spaces, facilitating revival by enabling accessible transcription and reducing barriers to fluency maintenance amid low-resource digital status.[100][97]Traditional Culture and Beliefs

Kinship Systems and Social Norms

The Sakha (Yakut) kinship system centers on patrilineal clans, termed aga or aqa-usa, which organize descent through male lines tracing back to shared ancestors, frequently mythic progenitors documented in ethnographic records. These clans function as exogamous units, enforcing marriage prohibitions within the group to foster alliances and avert consanguinity, a practice integral to maintaining social cohesion across dispersed settlements.[3][101] Patrilineage membership typically spans nine generations, prioritizing paternal kinship ties while incorporating maternal clans (je-usa) for extended relations, thereby structuring inheritance, dispute resolution, and resource allocation among kin. Clan affiliations historically delimited territories and obligations, with leaders (toyons) mediating internal hierarchies based on genealogical seniority.[3][101] Gender norms in traditional Sakha society delineated labor by sex, with women overseeing cattle and horse herding, including milking and hide processing, adapted to the demands of pastoral mobility in subarctic conditions. Men, conversely, focused on hunting, fishing, and warfare, including raids for livestock that reinforced clan prestige and economic viability prior to Russian conquest. These roles, rooted in ecological necessities, exhibit persistence in rural Sakha communities, where ethnographic observations note women's continued primacy in domestic animal management amid male out-migration for wage labor.[102] Clan reciprocity mechanisms, emphasizing aid during scarcities such as the 18th-19th century famines, provided adaptive resilience by pooling kin resources more reliably than sporadic imperial relief, as substantiated by survival disparities in clan-cohesive versus isolated households.[103][54]Shamanistic Practices and Worldview

The traditional Sakha worldview encompasses an animistic cosmology structured into three interconnected realms: the upper world inhabited by benevolent creator deities (aiyy), the middle world of human existence and natural phenomena, and the lower world associated with malevolent spirits (abaasy) and the deceased. Shamans, termed oyuun, function as mediators between these realms, employing ecstatic rituals involving rhythmic drumming, chanting, and trance states to negotiate with spirits, diagnose illnesses attributed to spiritual imbalances, and restore harmony. These practices, documented in 19th-century ethnographies such as those by Russian explorers in the Yakutsk region, emphasize empirical observation of ritual efficacy in communal healing and decision-making rather than unverifiable supernatural interventions.[104][105][106] Central to these rituals are beliefs in animal spirits as potent intermediaries, with horses revered for their symbolic role in traversing worlds and ensuring ritual potency; white stallions were selectively sacrificed to appease upper-world deities or avert lower-world threats, a practice rooted in the Sakha's equestrian adaptation to subarctic steppes. Such sacrifices, performed during seasonal ceremonies, correlated with heightened group cohesion and psychological resilience amid environmental hardships, though no causal evidence supports claims of otherworldly influence beyond placebo-like social mechanisms. Post-1930s Soviet suppression, which targeted shamans as counter-revolutionary elements, led to near-eradication of overt practices by the mid-20th century, displacing them into clandestine or syncretic forms.[107][108][109] From the 1990s, following the Soviet collapse, a neo-shamanic revival emerged in the Sakha Republic, blending reconstructed rituals with modern therapeutic applications, as seen in urban healing circles and cultural festivals reinvigorating oyuun roles for mental health support. This resurgence, while functionally adaptive for identity preservation amid demographic shifts, often incorporates eclectic elements from global New Age influences, diluting pre-Soviet purity without empirical demonstration of enhanced outcomes over secular alternatives. Academic analyses note its correlation with post-industrial identity crises rather than validated spiritual efficacy, underscoring shamanism's historical utility as a pragmatic framework for interpreting causality in unpredictable taiga ecosystems.[110][111][112]Folklore, Epic Traditions, and Oral Heritage

The Olonkho constitutes the core of Yakut (Sakha) epic traditions, encompassing a vast corpus of heroic narratives transmitted orally across generations. These epics, ranging from 10,000 to 15,000 verses in length, depict protagonists such as Nyurgun Bootur engaging in cosmic battles against abyssal demons (abaasy), safeguarding the middle world from existential threats.[62] [113] Performed by specialized rhapsodists known as olonkhosut, the tales unfold in a dual format: melodic sung verses for invocations and dialogues, interspersed with prosaic narration for descriptive passages.[62] [114] This performative style, rooted in Turkic antiquity, preserved genealogical lineages and migratory histories, with motifs reflecting southward origins before northward displacements into Siberian taiga by the 13th–15th centuries.[15] [3] Central themes revolve around tripartite cosmology—upper realm of benevolent deities (aiyy), terrestrial human domain, and infernal abyss—where heroes embody clan progenitors defending harmony against chaos.[113] [15] Narratives encode empirical kernels of ethnogenesis, such as southward kin alliances and adaptive survival strategies, verifiable through comparative analysis with Altaic epics like those of Mongolic groups.[115] Oral chains maintained fidelity via mnemonic formulas and hereditary transmission among olonkhosut, often spanning multi-night recitals until Soviet disruptions in the early 20th century curtailed communal performances.[114] [116] UNESCO recognized Olonkho as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2005, elevating it to the Representative List by 2008, which spurred documentation efforts amid urbanization's erosion of traditional venues.[62] [117] In the 2020s, initiatives like the 2023 Interregional Festival "New Olonkho" have facilitated audio-visual recordings of variants, capturing regional divergences such as northern motifs of sacred trees and abyssal incursions, thereby archiving mnemonic data for historical reconstruction.[118] [119] These efforts underscore Olonkho's role as a repository of verifiable ancestral knowledge, distinct from interpretive overlays.[120]Economy and Livelihoods

Subsistence Foundations: Herding and Hunting

The traditional subsistence of the Yakuts centered on pastoral herding of horses and cattle, which provided the caloric foundation through meat, milk, and labor, with reindeer herding playing a secondary role among northern subgroups.[121] Yakutian horses, bred for endurance in subarctic conditions, supported mobility and served as a primary wealth indicator, while cattle offered dairy yields essential for nutrition in environments where crop cultivation was marginal.[122] These Arctic-adapted breeds enabled year-round grazing and milk production despite prolonged winters, with Yakutian cattle maintaining activity at temperatures down to -50°C and averaging 1,000–1,112 kg of milk annually, characterized by elevated fat (5.03%) and protein content for energy-dense sustenance.[123] [124] Seasonal transhumance involved moving herds between forested winter shelters and open summer pastures like alaas meadows, typically spanning 10–20 km to access forage, sustaining herds documented in 19th-century accounts as numbering in the hundreds per affluent household.[125] This system remained viable into the early 20th century, as tsarist-era records indicate stable pastoral outputs without overgrazing, bolstered by practices such as fermented dairy products— including kurut and tarasun—which preserved milk's nutritional value through lactic fermentation, yielding probiotics and bioavailable nutrients critical for winter survival.[126] Such adaptations supported population densities higher than those of neighboring Evenk or Yukaghir hunter-gatherers, who relied more on sparse wild resources, allowing Yakut clans to maintain semi-sedentary communities exceeding 1–2 persons per 100 km² in fertile valleys pre-1930.[71] Hunting and fishing supplemented herding, targeting elk, reindeer, and fish like muksun and salmon for protein and fats during off-seasons, with spring and winter pursuits of large game providing hides and meat reserves.[127] These activities, conducted via traps, bows, and ice fishing, contributed 20–30% of caloric intake in lean periods but were secondary to livestock-derived yields, ensuring resilience in a taiga ecosystem where herding's reliability outpaced purely extractive foraging.[128]Industrial Shifts: Diamonds, Gold, and Energy