Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biomolecular structure

View on WikipediaThis article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (February 2016) |

|

|

Biomolecular structure is the intricate folded, three-dimensional shape that is formed by a molecule of protein, DNA, or RNA, and that is important to its function. The structure of these molecules may be considered at any of several length scales ranging from the level of individual atoms to the relationships among entire protein subunits. This useful distinction among scales is often expressed as a decomposition of molecular structure into four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. The scaffold for this multiscale organization of the molecule arises at the secondary level, where the fundamental structural elements are the molecule's various hydrogen bonds. This leads to several recognizable domains of protein structure and nucleic acid structure, including such secondary-structure features as alpha helixes and beta sheets for proteins, and hairpin loops, bulges, and internal loops for nucleic acids. The terms primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure were introduced by Kaj Ulrik Linderstrøm-Lang in his 1951 Lane Medical Lectures at Stanford University.

Primary structure

[edit]The primary structure of a biopolymer is the exact specification of its atomic composition and the chemical bonds connecting those atoms (including stereochemistry). For a typical unbranched, un-crosslinked biopolymer (such as a molecule of a typical intracellular protein, or of DNA or RNA), the primary structure is equivalent to specifying the sequence of its monomeric subunits, such as amino acids or nucleotides.

The primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino N-terminus to the carboxyl C-terminus, while the primary structure of DNA or RNA molecule is known as the nucleic acid sequence reported from the 5' end to the 3' end. The nucleic acid sequence refers to the exact sequence of nucleotides that comprise the whole molecule. Often, the primary structure encodes sequence motifs that are of functional importance. Some examples of such motifs are: the C/D[1] and H/ACA boxes[2] of snoRNAs, LSm binding site found in spliceosomal RNAs such as U1, U2, U4, U5, U6, U12 and U3, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence,[3] the Kozak consensus sequence[4] and the RNA polymerase III terminator.[5]

Secondary structure

[edit]

The secondary structure of a protein is the pattern of hydrogen bonds in a biopolymer. These determine the general three-dimensional form of local segments of the biopolymers, but does not describe the global structure of specific atomic positions in three-dimensional space, which are considered to be tertiary structure. Secondary structure is formally defined by the hydrogen bonds of the biopolymer, as observed in an atomic-resolution structure. In proteins, the secondary structure is defined by patterns of hydrogen bonds between backbone amine and carboxyl groups (sidechain–mainchain and sidechain–sidechain hydrogen bonds are irrelevant), where the DSSP definition of a hydrogen bond is used.

The secondary structure of a nucleic acid is defined by the hydrogen bonding between the nitrogenous bases.

For proteins, however, the hydrogen bonding is correlated with other structural features, which has given rise to less formal definitions of secondary structure. For example, helices can adopt backbone dihedral angles in some regions of the Ramachandran plot; thus, a segment of residues with such dihedral angles is often called a helix, regardless of whether it has the correct hydrogen bonds. Many other less formal definitions have been proposed, often applying concepts from the differential geometry of curves, such as curvature and torsion. Structural biologists solving a new atomic-resolution structure will sometimes assign its secondary structure by eye and record their assignments in the corresponding Protein Data Bank (PDB) file.

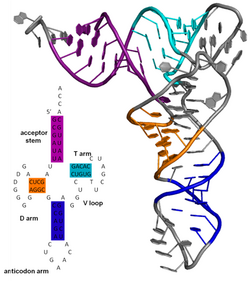

The secondary structure of a nucleic acid molecule refers to the base pairing interactions within one molecule or set of interacting molecules. The secondary structure of biological RNA's can often be uniquely decomposed into stems and loops. Often, these elements or combinations of them can be further classified, e.g. tetraloops, pseudoknots and stem loops. There are many secondary structure elements of functional importance to biological RNA. Famous examples include the Rho-independent terminator stem loops and the transfer RNA (tRNA) cloverleaf. There is a minor industry of researchers attempting to determine the secondary structure of RNA molecules. Approaches include both experimental and computational methods (see also the List of RNA structure prediction software).

Tertiary structure

[edit]The tertiary structure of a protein or any other macromolecule is its three-dimensional structure, as defined by the atomic coordinates.[6] Proteins and nucleic acids fold into complex three-dimensional structures which result in the molecules' functions. While such structures are diverse and complex, they are often composed of recurring, recognizable tertiary structure motifs and domains that serve as molecular building blocks. Tertiary structure is considered to be largely determined by the biomolecule's primary structure (its sequence of amino acids or nucleotides).

Quaternary structure

[edit]The protein quaternary structure [a] refers to the number and arrangement of multiple protein molecules in a multi-subunit complex.

For nucleic acids, the term is less common, but can refer to the higher-level organization of DNA in chromatin,[7] including its interactions with histones, or to the interactions between separate RNA units in the ribosome[8][9] or spliceosome.

Viruses, in general, can be regarded as molecular machines. Bacteriophage T4 is a particularly well studied virus and its protein quaternary structure is relatively well defined.[10] A study by Floor (1970)[11] showed that, during the in vivo construction of the virus by specific morphogenetic proteins, these proteins need to be produced in balanced proportions for proper assembly of the virus to occur. Insufficiency (due to mutation) in the production of one particular morphogenetic protein (e.g. a critical tail fiber protein), can lead to the production of progeny viruses almost all of which have too few of the particular protein component to properly function, i.e. to infect host cells.[11] However, a second mutation that reduces another morphogenetic component (e.g. in the base plate or head of the phage) could in some cases restore a balance such that a higher proportion of the virus particles produced are able to function.[11] Thus it was found that a mutation that reduces expression of one gene, whose product is employed in morphogenesis, may be partially suppressed by a mutation that reduces expression of a second morphogenetic gene resulting in a more balanced production of the virus gene products. The concept that, in vivo, a balanced availability of components is necessary for proper molecular morphogenesis may have general applicability for understanding the assembly of protein molecular machines.

Structure determination

[edit]Structure probing is the process by which biochemical techniques are used to determine biomolecular structure.[12] This analysis can be used to define the patterns that can be used to infer the molecular structure, experimental analysis of molecular structure and function, and further understanding on development of smaller molecules for further biological research.[13] Structure probing analysis can be done through many different methods, which include chemical probing, hydroxyl radical probing, nucleotide analog interference mapping (NAIM), and in-line probing.[12]

Protein and nucleic acid structures can be determined using either nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) or X-ray crystallography or single-particle cryo electron microscopy (cryoEM). The first published reports for DNA (by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling in 1953) of A-DNA X-ray diffraction patterns—and also B-DNA—used analyses based on Patterson function transforms that provided only a limited amount of structural information for oriented fibers of DNA isolated from calf thymus.[14][15] An alternate analysis was then proposed by Wilkins et al. in 1953 for B-DNA X-ray diffraction and scattering patterns of hydrated, bacterial-oriented DNA fibers and trout sperm heads in terms of squares of Bessel functions.[16] Although the B-DNA form' is most common under the conditions found in cells,[17] it is not a well-defined conformation but a family or fuzzy set of DNA conformations that occur at the high hydration levels present in a wide variety of living cells.[18] Their corresponding X-ray diffraction & scattering patterns are characteristic of molecular paracrystals with a significant degree of disorder (over 20%),[19][20] and the structure is not tractable using only the standard analysis.

In contrast, the standard analysis, involving only Fourier transforms of Bessel functions[21] and DNA molecular models, is still routinely used to analyze A-DNA and Z-DNA X-ray diffraction patterns.[22]

Structure prediction

[edit]

Biomolecular structure prediction is the prediction of the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence, or of a nucleic acid from its nucleobase (base) sequence. In other words, it is the prediction of secondary and tertiary structure from its primary structure. Structure prediction is the inverse of biomolecular design, as in rational design, protein design, nucleic acid design, and biomolecular engineering.

Protein structure prediction is one of the most important goals pursued by bioinformatics and theoretical chemistry. Protein structure prediction is of high importance in medicine (for example, in drug design) and biotechnology (for example, in the design of novel enzymes). Every two years, the performance of current methods is assessed in the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiment.

There has also been a significant amount of bioinformatics research directed at the RNA structure prediction problem. A common problem for researchers working with RNA is to determine the three-dimensional structure of the molecule given only the nucleic acid sequence. However, in the case of RNA, much of the final structure is determined by the secondary structure or intra-molecular base-pairing interactions of the molecule. This is shown by the high conservation of base pairings across diverse species.

Secondary structure of small nucleic acid molecules is determined largely by strong, local interactions such as hydrogen bonds and base stacking. Summing the free energy for such interactions, usually using a nearest-neighbor method, provides an approximation for the stability of given structure.[23] The most straightforward way to find the lowest free energy structure would be to generate all possible structures and calculate the free energy for them, but the number of possible structures for a sequence increases exponentially with the length of the molecule.[24] For longer molecules, the number of possible secondary structures is vast.[23]

Sequence covariation methods rely on the existence of a data set composed of multiple homologous RNA sequences with related but dissimilar sequences. These methods analyze the covariation of individual base sites in evolution; maintenance at two widely separated sites of a pair of base-pairing nucleotides indicates the presence of a structurally required hydrogen bond between those positions. The general problem of pseudoknot prediction has been shown to be NP-complete.[25]

Design

[edit]Biomolecular design can be considered the inverse of structure prediction. In structure prediction, the structure is determined from a known sequence, whereas, in protein or nucleic acid design, a sequence that will form a desired structure is generated.

Other biomolecules

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

Other biomolecules, such as polysaccharides, polyphenols and lipids, can also have higher-order structure of biological consequence.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Here quaternary means "fourth-level structure", not "four-way interaction". Etymologically quartary is correct: quaternary is derived from Latin distributive numbers, and follows binary and ternary; while quartary is derived from Latin ordinal numbers, and follows secondary and tertiary. However, quaternary is standard in biology.

References

[edit]- ^ Samarsky DA, Fournier MJ, Singer RH, Bertrand E (July 1998). "The snoRNA box C/D motif directs nucleolar targeting and also couples snoRNA synthesis and localization". The EMBO Journal. 17 (13): 3747–57. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.13.3747. PMC 1170710. PMID 9649444.

- ^ Ganot P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T (April 1997). "The family of box ACA small nucleolar RNAs is defined by an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure and ubiquitous sequence elements essential for RNA accumulation". Genes & Development. 11 (7): 941–56. doi:10.1101/gad.11.7.941. PMID 9106664.

- ^ Shine J, Dalgarno L (March 1975). "Determinant of cistron specificity in bacterial ribosomes". Nature. 254 (5495): 34–38. Bibcode:1975Natur.254...34S. doi:10.1038/254034a0. PMID 803646. S2CID 4162567.

- ^ Kozak M (October 1987). "An analysis of 5'-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs". Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (20): 8125–48. doi:10.1093/nar/15.20.8125. PMC 306349. PMID 3313277.

- ^ Bogenhagen DF, Brown DD (April 1981). "Nucleotide sequences in Xenopus 5S DNA required for transcription termination". Cell. 24 (1): 261–70. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(81)90522-5. PMID 6263489. S2CID 9982829.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "tertiary structure". doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06282

- ^ Sipski ML, Wagner TE (March 1977). "Probing DNA quaternary ordering with circular dichroism spectroscopy: studies of equine sperm chromosomal fibers". Biopolymers. 16 (3): 573–82. doi:10.1002/bip.1977.360160308. PMID 843604. S2CID 35930758.

- ^ Noller HF (1984). "Structure of ribosomal RNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 53: 119–62. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001003. PMID 6206780.

- ^ Nissen P, Ippolito JA, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA (April 2001). "RNA tertiary interactions in the large ribosomal subunit: the A-minor motif". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (9): 4899–903. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.4899N. doi:10.1073/pnas.081082398. PMC 33135. PMID 11296253.

- ^ Leiman PG, Kanamaru S, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Rossmann MG (November 2003). "Structure and morphogenesis of bacteriophage T4". Cell Mol Life Sci. 60 (11): 2356–70. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3072-1. PMC 11138918. PMID 14625682.

- ^ a b c Floor E (February 1970). "Interaction of morphogenetic genes of bacteriophage T4". J Mol Biol. 47 (3): 293–306. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(70)90303-7. PMID 4907266.

- ^ a b Teunissen, A. W. M. (1979). RNA Structure Probing: Biochemical structure analysis of autoimmune-related RNA molecules. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-90-901323-4-1.

- ^ Pace NR, Thomas BC, Woese CR (1999). Probing RNA Structure, Function, and History by Comparative Analysis. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 113–17. ISBN 978-0-87969-589-7.

- ^ Franklin RE, Gosling RG (6 March 1953). "The Structure of Sodium Thymonucleate Fibres (I. The Influence of Water Content, and II. The Cylindrically Symmetrical Patterson Function)" (PDF). Acta Crystallogr. 6 (8): 673–78. doi:10.1107/s0365110x53001939.

- ^ Franklin RE, Gosling RG (April 1953). "Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate". Nature. 171 (4356): 740–41. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..740F. doi:10.1038/171740a0. PMID 13054694. S2CID 4268222.

- ^ Wilkins MH, Stokes AR, Wilson HR (April 1953). "Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids". Nature. 171 (4356): 738–40. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..738W. doi:10.1038/171738a0. PMID 13054693. S2CID 4280080.

- ^ Leslie AG, Arnott S, Chandrasekaran R, Ratliff RL (October 1980). "Polymorphism of DNA double helices". Journal of Molecular Biology. 143 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(80)90124-2. PMID 7441761.

- ^ Baianu, I. C. (1980). "Structural Order and Partial Disorder in Biological systems". Bull. Math. Biol. 42 (1): 137–41. doi:10.1007/BF02462372. S2CID 189888972.

- ^ Hosemann R, Bagchi RN (1962). Direct analysis of diffraction by matter. Amsterdam/New York: North-Holland.

- ^ Baianu IC (1978). "X-ray scattering by partially disordered membrane systems". Acta Crystallogr. A. 34 (5): 751–53. Bibcode:1978AcCrA..34..751B. doi:10.1107/s0567739478001540.

- ^ "Bessel functions and diffraction by helical structures". planetphysics.org.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "X-Ray Diffraction Patterns of Double-Helical Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Crystals". planetphysics.org. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009.

- ^ a b Mathews DH (June 2006). "Revolutions in RNA secondary structure prediction". Journal of Molecular Biology. 359 (3): 526–32. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.067. PMID 16500677.

- ^ Zuker M, Sankoff D (1984). "RNA secondary structures and their prediction". Bull. Math. Biol. 46 (4): 591–621. doi:10.1007/BF02459506. S2CID 189885784.

- ^ Lyngsø RB, Pedersen CN (2000). "RNA pseudoknot prediction in energy-based models". Journal of Computational Biology. 7 (3–4): 409–27. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.34.4044. doi:10.1089/106652700750050862. PMID 11108471.

-en.svg/250px-Protein_structure_(full)-en.svg.png)

-en.svg/1229px-Protein_structure_(full)-en.svg.png)