Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Respiratory tract

View on Wikipedia| Respiratory tract | |

|---|---|

Conducting passages | |

| Details | |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 265130 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

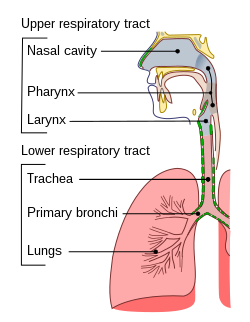

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of conducting air to the alveoli for the purposes of gas exchange in mammals.[1] The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.[2]

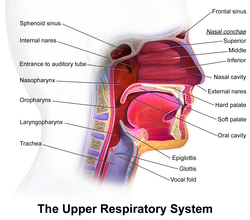

Air is breathed in through the nose to the nasal cavity, where a layer of nasal mucosa acts as a filter and traps pollutants and other harmful substances found in the air. Next, air moves into the pharynx, a passage that contains the intersection between the oesophagus and the larynx. The opening of the larynx has a special flap of cartilage, the epiglottis, that opens to allow air to pass through but closes to prevent food from moving into the airway.

From the larynx, air moves into the trachea and down to the intersection known as the carina that branches to form the right and left primary (main) bronchi. Each of these bronchi branches into a secondary (lobar) bronchus that branches into tertiary (segmental) bronchi, that branch into smaller airways called bronchioles that eventually connect with tiny specialized structures called alveoli that function in gas exchange.

The lungs which are located in the thoracic cavity, are protected from physical damage by the rib cage. At the base of the lungs is a sheet of skeletal muscle called the diaphragm. The diaphragm separates the lungs from the stomach and intestines. The diaphragm is also the main muscle of respiration involved in breathing, and is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system.

The lungs are encased in a serous membrane that folds in on itself to form the pleurae – a two-layered protective barrier. The inner visceral pleura covers the surface of the lungs, and the outer parietal pleura is attached to the inner surface of the thoracic cavity. The pleurae enclose a cavity called the pleural cavity that contains pleural fluid. This fluid is used to decrease the amount of friction that lungs experience during breathing.

Structure

[edit]

The respiratory tract is divided into the upper airways and lower airways. The upper airways or upper respiratory tract includes the nose and nasal passages, paranasal sinuses, the pharynx, and the portion of the larynx above the vocal folds (cords). The lower airways or lower respiratory tract includes the portion of the larynx below the vocal folds, trachea, bronchi and bronchioles. The lungs can be included in the lower respiratory tract or as separate entity and include the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli.[3]

The respiratory tract can also be divided into a conducting zone and a respiratory zone, based on the distinction of transporting gases or exchanging them.

The conducting zone includes structures outside of the lungs – the nose, pharynx, larynx, and trachea, and structures inside the lungs – the bronchi, bronchioles, and terminal bronchioles. The conduction zone conducts air breathed in that is filtered, warmed, and moistened, into the lungs. It represents the 1st through the 16th division of the respiratory tract. The conducting zone is most of the respiratory tract that conducts gases into and out of the lungs but excludes the respiratory zone that exchanges gases. The conducting zone also functions to offer a low resistance pathway for airflow. It provides a major defense role in its filtering abilities.

The respiratory zone includes the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli, and is the site of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange with the blood. The respiratory bronchioles and the alveolar ducts are responsible for 10% of the gas exchange. The alveoli are responsible for the other 90%. The respiratory zone represents the 16th through the 23rd division of the respiratory tract.

From the bronchi, the dividing tubes become progressively smaller with an estimated 20 to 23 divisions before ending at an alveolus.[1]

Upper respiratory tract

[edit]

The upper respiratory tract can refer to the parts of the respiratory system lying above the vocal folds, or above the cricoid cartilage.[4][5] The larynx is sometimes included in both the upper and lower airways.[6] The larynx is also called the voice box and has the associated cartilage that produces sound. The tract consists of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, the pharynx (nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx) and sometimes includes the larynx.

Lower respiratory tract

[edit]

The lower respiratory tract or lower airway is derived from the developing foregut and consists of the trachea, bronchi (primary, secondary and tertiary), bronchioles (including terminal and respiratory), and lungs (including alveoli).[7] It also sometimes includes the larynx.

The lower respiratory tract is also called the respiratory tree or tracheobronchial tree, to describe the branching structure of airways supplying air to the lungs, and includes the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles.[8]

- trachea

- main bronchus (diameter approximately 1 – 1.4 cm in adults)[9]

- lobar bronchus (diameter approximately 1 cm)

- segmental bronchus (diameter 4.5 to 13 mm)[9]

- subsegmental bronchus (diameter 1 to 6 mm)[9]

- segmental bronchus (diameter 4.5 to 13 mm)[9]

- lobar bronchus (diameter approximately 1 cm)

- main bronchus (diameter approximately 1 – 1.4 cm in adults)[9]

At each division point or generation, one airway branches into two smaller airways. The human respiratory tree may consist on average of 23 generations, while the respiratory tree of the mouse has up to 13 generations. Proximal divisions (those closest to the top of the tree, such as the bronchi) mainly function to transmit air to the lower airways. Later divisions including the respiratory bronchiole, alveolar ducts, and alveoli, are specialized for gas exchange.

The trachea is the largest tube in the respiratory tract and consists of tracheal rings of hyaline cartilage. It branches off into two bronchial tubes, a left and a right main bronchus. The bronchi branch off into smaller sections inside the lungs, called bronchioles. These bronchioles give rise to the air sacs in the lungs called the alveoli.[10]

The lungs are the largest organs in the lower respiratory tract. The lungs are suspended within the pleural cavity of the thorax. The pleurae are two thin membranes, one cell layer thick, which surround the lungs. The inner (visceral pleura) covers the lungs and the outer (parietal pleura) lines the inner surface of the chest wall. This membrane secretes a small amount of fluid, allowing the lungs to move freely within the pleural cavity while expanding and contracting during breathing. The lungs are divided into different lobes. The right lung is larger in size than the left, because of the heart's being situated to the left of the midline. The right lung has three lobes – upper, middle, and lower (or superior, middle, and inferior), and the left lung has two – upper and lower (or superior and inferior), plus a small tongue-shaped portion of the upper lobe known as the lingula. Each lobe is further divided up into segments called bronchopulmonary segments. Each lung has a costal surface, which is adjacent to the ribcage; a diaphragmatic surface, which faces downward toward the diaphragm; and a mediastinal surface, which faces toward the center of the chest, and lies against the heart, great vessels, and the carina where the two mainstem bronchi branch off from the base of the trachea.

The alveoli are tiny air sacs in the lungs where gas exchange takes place. The mean number of alveoli in a human lung is 480 million.[11] When the diaphragm contracts, a negative pressure is generated in the thorax and air rushes in to fill the cavity. When that happens, these sacs fill with air, making the lung expand. The alveoli are rich with capillaries, called alveolar capillaries. Here the red blood cells absorb oxygen from the air and then carry it back in the form of oxyhaemaglobin, to nourish the cells. The red blood cells also carry carbon dioxide (CO2) away from the cells in the form of carbaminohemoglobin and release it into the alveoli through the alveolar capillaries. When the diaphragm relaxes, a positive pressure is generated in the thorax and air rushes out of the alveoli expelling the carbon dioxide.

Microanatomy

[edit]

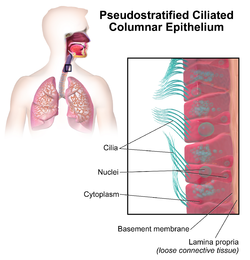

The respiratory tract is covered in epithelium, which varies down the tract. There are glands and mucus produced by goblet cells in parts, as well as smooth muscle, elastin or cartilage. The epithelium from the nose to the bronchioles is covered in ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, commonly called respiratory epithelium.[12] The cilia beat in one direction, moving mucus towards the throat where it is swallowed. Moving down the bronchioles, the cells get more cuboidal in shape but are still ciliated.

Glands are abundant in the upper respiratory tract, but there are fewer lower down and they are absent starting at the bronchioles. The same goes for goblet cells, although there are scattered ones in the first bronchioles.

Cartilage is present until the bronchioles. In the trachea, they are C-shaped rings of hyaline cartilage, whereas in the bronchi the cartilage takes the form of interspersed plates. Smooth muscle starts in the trachea, where it joins the C-shaped rings of cartilage. It continues down the bronchi and bronchioles, which it completely encircles. Instead of hard cartilage, the bronchi and bronchioles are composed of elastic tissue.

The lungs are made up of thirteen different kinds of cells, eleven types of epithelial cell and two types of mesenchymal cell.[13] The epithelial cells form the lining of the tracheal, and bronchial tubes, while the mesenchymal cells line the lungs.

-

Differences in cells along the respiratory tract

-

Transverse section of tracheal tissue. Note that image is incorrectly labeled "ciliated stratified epithelium" at upper right.

Function

[edit]Most of the respiratory tract exists merely as a piping system for air to travel in the lungs, and alveoli are the only part of the lung that exchanges oxygen and carbon dioxide with the blood.

Respiration

[edit]Respiration is the rhythmical process of breathing, in which air is drawn into the alveoli of the lungs via inhalation and subsequently expelled via exhalation. When a human being inhales, air travels down the trachea, through the bronchial tubes, and into the lungs. The entire tract is protected by the rib cage, spine, and sternum. In the lungs, oxygen from the inhaled air is transferred into the blood and circulated throughout the body. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is transferred from returning blood back into gaseous form in the lungs and exhaled through the lower respiratory tract and then the upper, to complete the process of breathing.

Unlike the trachea and bronchi, the upper airway is a collapsible, compliant tube. As such, it has to be able to withstand suction pressures generated by the rhythmic expansion of the thoracic cavity that sucks air into the lungs. This is accomplished by the contraction of upper airway muscles during inhalation, such as the genioglossus (tongue) and the hyoid muscles. In addition to rhythmic innervation from the respiratory center in the medulla oblongata, the motor neurons controlling the muscles also receive tonic innervation that sets a baseline level of stiffness and size.

The diaphragm is the primary muscle that allows for lung expansion and contraction. Smaller muscles between the ribs, the external intercostals, assist with this process.

Defences against infection

[edit]The epithelial lining of the upper respiratory tract is interspersed with goblet cells that secrete a protective mucus. This helps to filter waste, which is eventually either swallowed into the highly acidic stomach environment or expelled via spitting. The epithelium lining the respiratory tract is covered in small hairs called cilia. These beat rhythmically out from the lungs, moving secreted mucus foreign particles toward the laryngopharynx upwards and outwards, in a process called mucociliary clearance, preventing mucus accumulation in the lungs. Macrophages in the alveoli are part of the immune system which engulf and digest any inhaled harmful agents.

Hair in the nostrils plays a protective role, trapping particulate matter such as dust.[14] These hairs, called vibrissae, are thicker than body hair and effectively block larger particles from entering the respiratory tract. They also increase the surface area for particle deposition, improving the nose's ability to filter pathogens.[15] The cough reflex expels all irritants within the mucous membrane to the outside. The airways of the lungs contain rings of muscle. When the passageways are irritated by some allergen, these muscles can constrict.

Clinical significance

[edit]The respiratory tract is a common site for infections.

Infection

[edit]Upper respiratory infection

[edit]Upper respiratory tract infections are probably the most common infections in the world.

The respiratory system is very prone to developing infections in the lungs. Infants and older adults are more likely to develop infections in their lungs because their lungs are not as strong in fighting off these infections. Most of these infections used to be fatal, but with new research and medicine, they are now treatable. With bacterial infections, antibiotics are prescribed, while viral infections are harder to treat but still curable.

The common cold, and flu are the most common causes of an upper respiratory tract infection, which can cause more serious illness that can develop in the lower respiratory tract.

Lower respiratory tract infections

[edit]Pneumonia is the most common, and frequent lower respiratory tract infection. This can be either viral, bacterial, or fungal. This infection is very common because pneumonia can be airborne, and when you inhale this infection in the air, the particles enter the lungs and move into the air sacs. This infection quickly develops in the lower part of the lung and fills the lung with fluid, and excess mucus. This causes difficulty in breathing and coughing as the lower respiratory tract tries to get rid of the fluid in the lungs. You can be more prone to developing this infection if you have asthma, flu, heart disease, or cancer[16]

Bronchitis is another common infection that takes place in the lower respiratory tract. It is an inflammation of the bronchial tubes. There are two forms of this infection: acute bronchitis, which is treatable and can go away without treatment, or chronic bronchitis, which comes and goes, but will always affect one's lungs. Bronchitis increases the amount of mucus that is natural in your respiratory tract. Chronic bronchitis is common in smokers, because the tar from smoking accumulates over time, causing the lungs to work harder to repair themselves.[17]

Tuberculosis is one of many other infections that occurs in the lower respiratory tract. You can contract this infection from airborne droplets, and if inhaled you are at risk of this disease. This is a bacterial infection that deteriorates the lung tissue resulting in coughing up blood.[18] This infection is deadly if not treated.

Cancer

[edit]

Some of these cancers have environmental causes such as smoking. When a tobacco product is inhaled, the smoke paralyzes the cilia, causing mucus to enter the lungs. Frequent smoking, over time, causes the cilia hairs to die and can no longer filter mucus. Tar from the smoke inhaled enters the lungs, turning the pink-coloured lungs black. The accumulation of this tar could eventually lead to lung cancer, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[7]

COPD

[edit]Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common lower respiratory disease that can be caused by exposure to harmful chemicals, or prolonged use of tobacco. This disease is chronic and progressive, the damage to the lungs is irreversible and eventually fatal. COPD destroys the alveoli, and lung tissue which makes breathing very difficult, causing shortness of breath, hyperventilation, and raised chest. The decreased number of alveoli causes loss of oxygen supply to the lungs and an increased accumulation of carbon dioxide. There are two types of COPD: primary and secondary.[citation needed] Primary COPD can be found in younger adults. This type of COPD deteriorates the air sacs, and lung mass. Secondary COPD can be found in older adults who smoke or have smoked and have a history of bronchitis. [citation needed] COPD includes symptoms of emphysema and chronic bronchitis.[19]

Asthma

[edit]

The bronchi are the main passages to the right and left lungs. These airways carry oxygen to the bronchioles inside the lungs. Inflammation of the bronchii and bronchioles can cause them to swell up, which could lead to an asthma attack. This results in wheezing, tightness of the chest, and severe difficulty in breathing. There are different types of asthma that affect the functions of the bronchial tubes. Allergies can also set off an allergic reaction, causing swelling of the bronchial tubes; as a result, the air passage will swell up, or close up completely.[20]

Mouth breathing

[edit]In general, air is inhaled through the nose. It can be inhaled through the mouth if it is not possible to breathe through the nose. However, chronic mouth breathing can cause a dry mouth and lead to infections.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Patwa A, Shah A (September 2015). "Anatomy and physiology of respiratory system relevant to anaesthesia". Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 59 (9): 533–541. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.165849. PMC 4613399. PMID 26556911.

- ^ "Respiratory mucosa". mesh..nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Respiratory tract". www.cancer.gov. 2 February 2011.

- ^ Ronald M. Perkin; James D Swift; Dale A Newton (1 September 2007). Pediatric hospital medicine: textbook of inpatient management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 473–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7032-3. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Jeremy P. T. Ward; Jane Ward; Charles M. Wiener (2006). The respiratory system at a glance. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-4051-3448-4. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Sabyasachi Sircar (2008). Principles of medical physiology. Thieme. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-3-13-144061-7. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Bronchial Anatomy". Retrieved 5 Mar 2014.

- ^ "Tracheobronchial tree | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Page 81 in Robert M. Kacmarek, Steven Dimas & Craig W. Mack (2013). Essentials of Respiratory Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-032327778-5.

- ^ "Human Respiratory System". Archived from the original on 2008-10-15. Retrieved 5 Oct 2008.

- ^ Ochs M, Nyengaard JR, Jung A, Knudsen L, Voigt M, Wahlers T, et al. (January 2004). "The number of alveoli in the human lung". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 169 (1): 120–124. doi:10.1164/rccm.200308-1107OC. PMID 14512270.

- ^ Moore EJ, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (2004). Trauma. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. p. 545. ISBN 0-07-137069-2. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ Breeze R, Turk M (April 1984). "Cellular structure, function and organization in the lower respiratory tract". Environmental Health Perspectives. 55: 3–24. Bibcode:1984EnvHP..55....3B. doi:10.1289/ehp.84553. PMC 1568358. PMID 6376102.

- ^ Blaivas AJ (29 June 2012). "Anatomy and function of the respiratory system". Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ Haghnegahdar A, Bharadwaj R, Feng Y (1 September 2023). "Exploring the role of nasal hair in inhaled airflow and coarse dust particle dynamics in a nasal cavity: A CFD-DEM study". Powder Technology. 427. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118710. Retrieved 2024-11-20.

- ^ "Pneumonia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Chest Cold (Acute Bronchitis)". Centers For Disease Control And Prevention. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Tuberculosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Emphysema: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 26 March 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Asthma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Your Nose, the Guardian of Your Lungs". Boston Medical Center. Retrieved 2020-06-29.