Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Religious Zionism

View on Wikipedia| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Israel |

|---|

|

Religious Zionism (Hebrew: צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, romanized: Tziyonut Datit) is a religious denomination that views Zionism as a fundamental component of Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as Dati Leumi (דָּתִי לְאֻמִּי, 'National Religious'), and in Israel, they are most commonly known by the plural form of the first part of that term: Datiim (דתיים, 'Religious'). The community is sometimes called 'Knitted kippah' (כִּפָּה סְרוּגָה, Kippah seruga), the typical head covering worn by male adherents to Religious Zionism.

Before the establishment of the State of Israel, most Religious Zionists were observant Jews who supported Zionist efforts to build a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. Religious Zionism revolves around three pillars: the Land of Israel, the People of Israel, and the Torah of Israel.[1] The Hardal (חרדי לאומי, Ḥaredi Le'umi, 'Nationalist Haredi') are a sub-community, stricter in its observance, and more statist in its politics. Those Religious Zionists who are less strict in their observance – although not necessarily more liberal in their politics – are informally referred to as "dati lite".[2]

History

[edit]

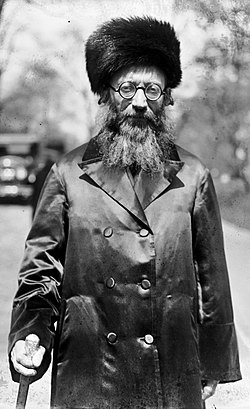

In 1862, German Orthodox Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer published his tractate Derishat Zion, positing that the salvation of the Jews, promised by the Prophets, can come about only by self-help.[3] Rabbi Moshe Shmuel Glasner was another prominent rabbi who supported Zionism. The main ideologue of modern Religious Zionism was Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who justified Zionism according to Jewish law, and urged young religious Jews to support efforts to settle the land, and the secular Labour Zionists to give more consideration to Judaism. Kook saw Zionism as a part of a divine scheme which would result in the resettlement of the Jewish people in its homeland. This would bring Geula ("salvation") to Jews, and then to the entire world. After world harmony is achieved by the re-foundation of the Jewish homeland, the Messiah will come. Although this has not yet happened, Kook emphasized that it would take time, and that the ultimate redemption happens in stages, often not apparent while happening. In 1924, when Kook became the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Mandatory Palestine, he tried to reconcile Zionism with Orthodox Judaism.

Ideology

[edit]

Religious Zionists believe that Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel) was promised to the ancient Israelites by God. Furthermore, modern Jews have the obligation to possess and defend the land in ways that comport with the Torah's high standards of justice.[4] To generations of diaspora Jews, Jerusalem has been a symbol of the Holy Land and of their return to it, as promised by God in numerous Biblical prophecies. Despite this, many Jews did not embrace Zionism before the 1930s, and certain religious groups opposed it then, as some groups still do now, on the grounds that an attempt to re-establish Jewish rule in Israel by human agency was blasphemous. Hastening salvation and the coming of the Messiah was considered religiously forbidden, and Zionism was seen as a sign of disbelief in God's power, and therefore, a rebellion against God.

Rabbi Kook developed a theological answer to that claim, which gave Zionism a religious legitimation: "Zionism was not merely a political movement by secular Jews. It was actually a tool of God to promote His divine scheme, and to initiate the return of the Jews to their homeland – the land He promised to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. God wants the children of Israel to return to their home in order to establish a Jewish sovereign state in which Jews could live according to the laws of Torah and Halakha, and commit the Mitzvot of Eretz Israel (these are religious commandments which can be performed only in the Land of Israel). Moreover, to cultivate the Land of Israel was a Mitzvah by itself, and it should be carried out. Therefore, settling Israel is an obligation of the religious Jews, and helping Zionism is actually following God's will."[5]

Socialist Zionism envisaged the movement as a tool for building an advanced socialist society in the land of Israel, while solving the problem of antisemitism. The early kibbutz was a communal settlement that focused on national goals, unencumbered by religion and precepts of Jewish law such as kashrut. Socialist Zionists were one of the results of a long process of modernization within the Jewish communities of Europe, known as the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. Rabbi Kook's answer was as follows:

Secular Zionists may think they do it for political, national, or socialist reasons, but in fact – the actual reason for them coming to resettle in Israel is a religious Jewish spark ("Nitzotz") in their soul, planted by God. Without their knowledge, they are contributing to the divine scheme and actually committing a great Mitzvah. The role of religious Zionists is to help them to establish a Jewish state and turn the religious spark in them into a great light. They should show them that the real source of Zionism and the longed-for Zion is Judaism and teach them Torah with love and kindness. In the end, they will understand that the laws of Torah are the key to true harmony and a socialist state (not in the Marxist meaning) that will be a light for the nations and bring salvation to the world.

Shlomo Avineri explained the last part of Kook's answer: "... and the end of those pioneers, who scout into the blindness of secularism and atheism, but the treasured light inside them leads them into the path of salvation – their end is that from doing Mitzva without purpose, they will do Mitzva with a purpose." (page 2221)

Ideological opposition to Zionism

[edit]Some Haredi Jews view establishing Jewish sovereignty in the Holy Land before the coming of the Messiah as forbidden, as a violation of the Three Oaths. This would apply whether those who established this sovereignty were religious or secular.[6]

Another reason Haredi Jews opposed Zionism that had nothing to do with the establishment of a state or immigration to Palestine was the ideology of secular Zionism itself. Zionism's goal was first and foremost a transformation of the Jewish People from a religious society – whose sole shared characteristic was the Torah – into a political nationality, with a common land, language, and culture.[6][7]

Elchonon Wasserman said:

The nationalist concept of the Jewish people as an ethnic or nationalistic entity has no place among us, and it's nothing but a foreign implant into Judaism; it is nothing but idolatry. And its younger sister, "religious nationalism (l'umis datis)", is idol worship that combines Hashem's name and heresy together (avodah zarah b'shituf).[8]

Chaim Brisker said, "The Zionists have already won because they got the Jews to look at themselves as a nation."[9]

Sholom Dovber Schneersohn, also known as the Rebbe Rashab, was the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe. He opposed both secular and religious Zionism. In 1903, he published Kuntres Uma'ayan, which included a strong criticism against Zionism. He was concerned that nationalism would replace Judaism as the basis of Jewish identity.[10]

Rav Elyashiv also denounced the actions of religious Jews joining Zionist organizations as separating from authentic Judaism. In 2010, Rav Elyashiv published a letter criticizing the Shas Party for joining the World Zionist Organization (WZO). He wrote that the Party "is turning its back on the basics of Charedi Jewry of the past hundred years. He compared this move to the decision of the Mizrachi movement to join the WZO [over one hundred years ago], which was the deciding factor in their separation from authentic Torah Judaism.[11][12]

Organizations

[edit]

The first rabbis to support Zionism were Yehuda Shlomo Alkalai and Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. They argued that the change in the status of Western Europe's Jews following emancipation was the first step toward redemption (גאולה), and that, therefore, one must hasten the messianic salvation by a natural salvation – whose main pillars are the Kibbutz Galuyot ("Gathering of the Exiles"), the return to Eretz Israel, agricultural work (עבודת אדמה), and the revival of the everyday use of the Hebrew language.

The Mizrachi organization was established in 1902 in Vilna at a world conference of Religious Zionists. It operates a youth movement, Bnei Akiva, which was founded in 1929. Mizrachi believes that the Torah should be at the centre of Zionism, a sentiment expressed in the Mizrachi Zionist slogan Am Yisrael B'Eretz Yisrael al pi Torat Yisrael ("The people of Israel in the land of Israel according to the Torah of Israel"). It also sees Jewish nationalism as a tool for achieving religious objectives. Mizrachi was the first official Religious Zionist party. It also built a network of religious schools that exist to this day.

In 1937–1948, the Religious Kibbutz Movement established three settlement blocs of three kibbutzim each. The first was in the Beit Shean Valley, the second was in the Hebron mountains south of Bethlehem (known as Gush Etzion), and the third was in the western Negev. Kibbutz Yavne was founded in the center of the country as the core of a fourth bloc that came into being after the establishment of the state.[13]

Political parties

[edit]The Labor Movement wing of Religious Zionism, founded in 1921 under the Zionist slogan "Torah va'Avodah" (Torah and Labor), was called HaPoel HaMizrachi. It represented religiously traditional Labour Zionists, both in Europe and in the Land of Israel, where it represented religious Jews in the Histadrut. In 1956, Mizrachi, HaPoel HaMizrachi, and other religious Zionists formed the National Religious Party (NRP) to advance the rights of religious Zionist Jews in Israel.

The NRP operated as an independent political party until the 2003 elections. In the 2006 elections, the NRP merged with the National Union (HaIchud HaLeumi). In the 2009 elections, the Jewish Home (HaBayit HaYehudi) was formed in place of the NRP.[14]

Other parties and groups affiliated with religious Zionism are Gush Emunim, Tkuma, and Meimad. Kahanism, a radical branch of religious Zionism, was founded by Rabbi Meir Kahane, whose party, Kach, was eventually banned from the Knesset.

Today, Otzma Yehudit and National Religious Party–Religious Zionism are the leading Dati Leumi parties.

Educational institutions

[edit]

The flagship religious institution of the Religious Zionist movement is the yeshiva founded by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook in 1924, called in his honor "Mercaz haRav" (lit. 'the Rabbi's center'). Other Religious Zionist yeshivot include Ateret Cohanim, Beit El yeshiva, and Yeshivat Or Etzion, founded by Rabbi Haim Druckman, a foremost disciple of Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook. Machon Meir is specifically outreach-focused.

There are approximately 90 Hesder yeshivot, allowing students to continue their Torah study during their National Service (see below). The first of these was Yeshivat Kerem B'Yavneh, established in 1954; the largest is the Hesder Yeshiva of Sderot, with over 800 students. Others which are well known include Yeshivat Har Etzion, Yeshivat HaKotel, Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in Maale Adumim, Yeshivat Har Bracha, Yeshivat Sha'alvim, and Yeshivat Har Hamor.[15]

These institutions usually offer a kollel for Semikha, or Rabbinic ordination. Students generally prepare for the Semikha test of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel (the "Rabbanut"); until his passing in 2020, often for that of the posek R. Zalman Nechemia Goldberg. Training as a Dayan (rabbinic judge) in this community is usually through Machon Ariel (Machon Harry Fischel), also founded by Rav Kook, or Kollel Eretz Hemda; the Chief Rabbinate also commonly. The Meretz Kollel has trained hundreds of community Rabbis.

Women study in institutions which are known as Midrashot (sing.: Midrasha) – prominent examples are Midreshet Ein HaNetziv and Migdal Oz. These are usually attended for one year either before or after sherut leumi. Various midrashot offer parallel degree coursework, and they may then be known as a machon. The Midrashot focus on Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and Machshavah (Jewish thought); some offer specialized training in Halakha: Nishmat certifies women as Yoatzot Halacha, Midreshet Lindenbaum as to'anot; Lindenbaum, Matan, and Ein HaNetziv offer Talmud-intensive programs in rabbinic-level halakha. Community education programs are offered by Emunah, and Matan, across the country.

For degree studies, many attend Bar Ilan University, which allows students to combine Torah study with university study, especially through its Machon HaGavoah LeTorah; Jerusalem College of Technology similarly (which also offers a Haredi track). There are also several colleges of education which are associated with the Hesder and the Midrashot, such as Herzog College, Talpiot, and the Lifshitz College of Education. These colleges often offer (master's level) specializations in Tanakh and Machshava.

High school students study at Mamlachti Dati (religious state) schools, [16] often associated with Bnei Akiva.[17] These schools offer intensive Torah study alongside the matriculation syllabus, and emphasize tradition and observance; see Education in Israel § Educational tracks. The first of these schools was established at Kfar Haroeh by Moshe-Zvi Neria in 1939; "Yashlatz", associated with Mercaz HaRav, was founded in 1964, and predates several schools similarly linked to Hesder yeshivot, such as that at Sha'alvim; see also the school-networks AMIT and Tachkemoni (Israel). Today, there are 60 such institutions, with more than 20,000 students. A Dati Leumi girls' high school is referred to as an "Ulpana"; a boys’ high school is a "Yeshiva Tichonit".

Some institutions are aligned with the Hardal community, with an ideology that is somewhat more "statist". The leading Yeshiva here is Har Hamor; several high schools also operate.

Politics

[edit]Most Religious Zionists embrace right-wing politics, especially the religious right-wing Jewish Home party and more recently the Religious Zionist Party, but many also support the mainstream right-wing Likud. There are also some left-wing Religious Zionists, such as Rabbi Michael Melchior, whose views were represented by the Meimad party (which ran together with the Israeli Labor party). Many Israeli settlers in the West Bank are Religious Zionists, along with most of the settlers forcibly expelled from the Gaza Strip in August and September 2005.

Military service

[edit]

Generally, all adult Jewish males and females in Israel are obligated to serve in the IDF. Certain segments of Orthodoxy defer their service, in order to engage in full-time Torah study for purpose of spiritual development in unison with warfare. Religious Zionist belief advocates that both are critical to Jewish survival and prosperity.

For this reason, many Religious Zionist men take part in the Hesder program, a concept conceived by Rabbi Yehuda Amital which allows military service to be combined with yeshiva studies.[18] Some others attend a pre-army Mechina educational program, delaying their service by one year. 88% of Hesder students belong to combat units, compared to a national average of below 30%. Students at Mercaz HaRav, and some Hardal yeshivot, undertake their service through a modified form of Hesder.

While some Religious Zionist women serve in the army, most choose national service, known as Sherut Leumi, instead (working at hospitals, schools, and day-care centers).[19] In November 2010, the IDF held a special conference which was attended by the heads of Religious Zionism, in order to encourage female Religious Zionists to join the IDF. The IDF undertook that all modesty and kosher issues will be handled, in order to make female Religious Zionists comfortable.

Dress

[edit]

Religious Zionists are often called Kippot sruggot, or "sruggim", in reference to the knitted or crocheted kippot (skullcaps; sing. kippah) which are worn by the men (although some of the men wear other types of head coverings, such as black velvet kippot). Otherwise – particularly for the "dati lite" – their style of dress is largely the same as secular Israelis, with jeans less common; on Shabbat, they wear a stereotypically white dress shirt (recently a polo shirt in some sectors), and often a white kippah. Women usually wear (long) skirts, and often cover their hair, usually with a hair accessory, as opposed to a sheitel (wig) in the Haredi style.

In the Hardal community, the dress is generally more formal, with an emphasis on appearing neat. The kippot, which are also knitted, are significantly larger, and it is common for tzitzit to be visibly worn, in keeping with the Haredi practice; payot (sidelocks) are similarly common, as is an (untrimmed) beard. Women invariably cover their hair – usually with a snood, or a mitpachat (Hebrew for "kerchief") – and often wear sandals; their skirts are longer and looser fitting. On Shabbat, men often wear a (blue) suit – atypical in Israel outside the Haredi world – and a large white crocheted kippah.

At prayer, the members of the community typically use the Koren Siddur or the Rinat Yisrael. Homes often have on their bookshelves a set of the Steinsaltz Talmud (much as the Artscroll is to be found in American Haredi homes), Mishnah with Kehati, Rambam La'Am, Peninei Halakha, and/or Tzurba M'Rabanan; as well as a selection of the numerous popular books by leading Dati Leumi figures on the weekly parsha, the festivals, and hashkafa (discussions on Jewish thought). Similar to Haredi families, more religious homes will also have all of "The Traditional Jewish Bookshelf".

Notable figures

[edit]Rabbis

[edit]- Yehuda Amital

- Yaakov Ariel

- Yisrael Ariel

- Shlomo Aviner

- Meir Bar-Ilan

- Yoel Bin-Nun

- Oury Amos Cherki

- She'ar Yashuv Cohen

- Zephaniah Drori

- Mordechai Eliyahu

- Baruch Gigi

- Shlomo Goren

- Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog

- Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

- Avraham Yitzchak Kook

- Zvi Yehuda Kook

- Aharon Lichtenstein

- Mosheh Lichtenstein

- Dov Lior

- Yaaqov Medan

- Zalman Baruch Melamd

- Eliezer Melamed

- Moshe-Zvi Neria

- Nahum Rabinovitch

- Shlomo Riskin

- Haim Sabato

- Eli Sadan

- David Samson

- Avraham Shapira

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik

- Zvi Thau

- Shaul Yisraeli

Politicians

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Adriana Kemp, Israelis in Conflict: Hegemonies, Identities, and Challenges, Sussex Academic Press, 2004, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Adina Newberg (2013). Elu v'Elu: Towards Integration of Identity and Multiple Narratives in the Jewish Renewal Sector in Israel Archived 2020-12-24 at the Wayback Machine, International Journal of Jewish Education Research, 2013 (5–6), 231–278); Chaim Cohen (n.d.). Torah Sociology: Dati Torani and Dati Liberal – Is Dialogue Desirable?, Israel National News.

- ^ Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- ^ Novak, David. "What Unites People of Faith across Religions, and Divides Them from Others." Mosaic. 23 January 2020. 23 January 2020.

- ^ Samson, David; Tzvi Fishman (1991). Torat Eretz Yisrael. Jerusalem: Torat Eretz Yisrael Publications.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Yaakov (2018). The empty wagon : Zionism's journey from identity crisis to identity theft. Bais Medrash Society. pp. 314–319. ISBN 978-1-64255-554-7. OCLC 1156725117.

- ^ M., Rabkin, Yakov (2006). A threat from within : a century of Jewish opposition to Zionism. Fernwood Pub. ISBN 978-1-84277-699-5. OCLC 1164387257.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wasserman, R. Elchonon. Kovetz Maamarim vol. 1 "Eretz Yisroel" (in Hebrew). p. 166.

- ^ Meler, Shim'on Yosef ben Elimelekh (2007–2015). The Brisker Rav: the life and times of maran hagaon haRav Yitzchok Ze'ev HaLevi Soloveichik. Daniel Weiss. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58330-969-8. OCLC 1043560561.

- ^ Goldman, Shalom (2009). Zeal for Zion : Christians, Jews, & the idea of the Promised Land. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3344-5. OCLC 317929525.

- ^ Yated Ne'eman, Parshas Bo, 2010

- ^ Ess, Em (2020-03-07). "Hefkervelt : An Open Letter Re WZO Elections by Harav Aharon Feldman Shlita". Hefkervelt. Retrieved 2022-01-23.

- ^ Yossi Katz, "Settlement clustering on a socio-cultural basis: The bloc settlement policy of the Religious Kibbutz Movement in Palestine", Journal of Rural Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 161–171, 1995

- ^ "National Religious Party".

- ^ See a listing of forty yeshivot at: https://toravoda.org.il/en/yeshivot-midrashot-general-map-high-school-graduates/

- ^ See the Hebrew Wikipedia's חינוך ממלכתי דתי generally, as well as ישיבה תיכונית and אולפנה, for further discussion, and a listing of schools.

- ^ See the Hebrew Wikipedia's מרכז ישיבות ואולפנות בני עקיבא.

- ^ See on army service tracks https://www.nbn.org.il//pre-draft/army-service-programs/

- ^ For information on Sherut Leumi, see, for e. g., https://www.nbn.org.il/sherut-leumi-national-service/

Further reading

[edit]- Avineri, Shlomo. The Zionist Idea and Its Variations. Am Oved publishing, chapter 17: "Rabbi Kook — the dialection in salvation".

- Aran, Gideon (2004) [1990]. "From Religious Zionism to Zionist Religion". In Goldscheider, Calvin; Neusner, Jacob (eds.). Social Foundations of Judaism (Reprint ed.). Eugene, Or: Wipf and Stock Publ. pp. 259–282. ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- Aran, Gideon (1991). "Jewish Zionist Fundamentalism: The Bloc of the Faithful in Israel (Gush Emunim)". In Marty, Martin E.; Appleby, R. Scott (eds.). Fundamentalisms Observed. The Fundamentalism Project, 1. Chicago, Il; London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 265–344. ISBN 0-226-50878-1.

- Deshen, Shlomo; Liebman, Charles S.; Shokeid, Moshe, eds. (2017) [1995]. "Part 4. Nationalist Orthodoxy". Israeli Judaism: The Sociology of Religion in Israel. Studies of Israeli Society, 7 (Reprint ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-56000-178-2.

- Gorny, Yosef (2003) [2000]. "Judaism and Zionism". In Neusner, Jacob; Avery-Peck, Alan J. (eds.). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism (Reprint ed.). Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publ. pp. 477–494. ISBN 1-57718-058-5.

- Halpern, Ben (2004) [1990]. "The Rise and Reception of Zionism in the Nineteenth Century". In Goldscheider, Calvin; Neusner, Jacob (eds.). Social Foundations of Judaism (Reprint ed.). Eugene, Or: Wipf and Stock Publ. pp. 94–113. ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- Neusner, Jacob (1989). Who, Where, and What Is “Israel”? Zionist Perspectives on Israeli and American Judaism. Lanham, Md: University Press of America Studies in Judaism.

- Neusner, Jacob (1991). "Judaism outside of Rabbinic Judaism: Zionism". An Introduction to Judaism: A Textbook and Reader. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox Press. pp. 309–322. ISBN 0-664-25348-2.

- Waxman, Chaim I., ed. (2008). Religious Zionism Post Disengagement: Future Directions. Orthodox Forum Series. New York: Michael Scharf Publ. Trust, Yeshiva University Press. ISBN 978-1-60280-022-9.

External links

[edit]- Religious Zionists of America

- Poster of Historic Religious Zionist Leaders Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- A Historical Look at Religious Zionism by Prof. Dan Michman

- Original Letters and Manuscripts: Zionism, Ben-Gurion on God's Promises Archived 2014-06-12 at the Wayback Machine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- "Kipa – House of Religious Zionism" (Hebrew)

- Official National Religious Party website (in English)

- Religious Zionism And Modern Orthodoxy, Rav Yosef Blau

- Religious Zionism, Compromise or Ideal?, hagshama.org.il

- The American Friends of YBA – Supporters of religious Zionist educational movement in Israel

Religious Zionism

View on GrokipediaReligious Zionism is an ideological synthesis of Orthodox Jewish religious observance and Zionist nationalism, positing the modern return to and sovereignty over the Land of Israel as an initial phase of divine redemption (atḥalta d'ge'ulah).[1][2] Emerging in the late 19th century amid rising European antisemitism and proto-Zionist stirrings, it was formalized politically through the Mizrachi movement, founded in 1902 by Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines as the religious faction within Theodor Herzl's World Zionist Organization, emphasizing practical settlement and Torah-centered national revival over messianic speculation.[2][3] The movement's theological foundation was profoundly shaped by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865–1935), who, as Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine, interpreted secular Zionist pioneering—even by non-observant Jews—as an unconscious manifestation of divine will toward redemption, integrating national activism with halakhic fidelity under the principle of Torah im Derech Eretz (Torah with the ways of the land).[1][4] This framework reconciled apparent tensions between religious traditionalism and modern state-building, fostering institutions like religious kibbutzim (e.g., Tirat Zvi, established 1937) and youth movements such as Bnei Akiva, which blended agricultural labor, military preparedness, and Torah study.[1] Post-independence, Religious Zionists formed the National Religious Party (NRP) in 1956, securing consistent Knesset representation and advancing policies for religious education, Sabbath observance in public life, and hesder yeshivot that combine rabbinic learning with IDF service, contributing disproportionately to military officer corps (over one-third of combat unit officers today).[5][1] Defining characteristics include a commitment to settling biblical territories (Judea, Samaria, Gaza pre-2005), viewing such acts as fulfilling commandments (mitzvot) tied to the land, and prioritizing collective Jewish sovereignty over individualistic liberalism, which has sustained communal resilience amid secular dominance in early Israeli society.[5][1] Achievements encompass educational networks like Bar-Ilan University and Merkaz HaRav Yeshiva, which have produced generations of rabbis, educators, and leaders integrating faith with professions in science, law, and security; the movement comprises about 10-12% of Israel's population (roughly 20% of Jews), wielding outsized influence in recent coalitions through parties like the Religious Zionist Party.[5] Controversies arise from post-1967 shifts toward activist messianism via Gush Emunim, which accelerated West Bank settlements as redemptive imperatives, sparking clashes with secular authorities and international diplomacy; fringe elements have engaged in vigilantism or extremism, though mainstream Religious Zionism maintains halakhic restraint and state loyalty, navigating internal debates over enlistment rates, gender roles in the military, and balancing religious authority with democratic pluralism.[1][5]