Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oral microbiology

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

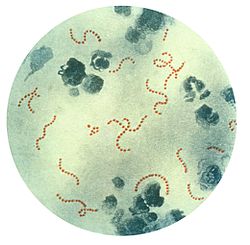

Oral microbiology is the study of the microorganisms (microbiota) of the oral cavity and their interactions between oral microorganisms or with the host.[1] The environment present in the human mouth is suited to the growth of characteristic microorganisms found there. It provides a source of water and nutrients, as well as a moderate temperature.[2] Resident microbes of the mouth adhere to the teeth and gums to resist mechanical flushing from the mouth to stomach where acid-sensitive microbes are destroyed by hydrochloric acid.[2][3]

Anaerobic bacteria in the oral cavity include: Actinomyces, Arachnia (Propionibacterium propionicus), Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, Fusobacterium, Lactobacillus, Leptotrichia, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Propionibacterium, Selenomonas, Treponema, and Veillonella.[4][needs update] The most commonly found protists are Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax.[5] Genera of fungi that are frequently found in the mouth include Candida, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Glomus, Alternaria, Penicillium, and Cryptococcus, among others.[6] Bacteria accumulate on both the hard and soft oral tissues in biofilms. Bacterial adhesion is particularly important for oral bacteria.

Oral bacteria have evolved mechanisms to sense their environment and evade or modify the host. Bacteria occupy the ecological niche provided by both the tooth surface and mucosal epithelium.[7][8] Factors of note that have been found to affect the microbial colonization of the oral cavity include the pH, oxygen concentration and its availability at specific oral surfaces, mechanical forces acting upon oral surfaces, salivary and fluid flow through the oral cavity, and age.[8] Interestingly, it has been observed that the oral microbiota differs between men and women in conditions of oral health, but especially during periodontitis.[9] However, a highly efficient innate host defense system constantly monitors the bacterial colonization and prevents bacterial invasion of local tissues. A dynamic equilibrium exists between dental plaque bacteria and the innate host defense system.[7] Of particular interest is the role of oral microorganisms in the two major dental diseases: dental caries and periodontal disease.[7]

Oral microflora

[edit]

The oral microbiome, mainly comprising bacteria which have developed resistance to the human immune system, has been known to impact the host for its own benefit, as seen with dental cavities. The environment present in the human mouth allows the growth of characteristic microorganisms found there. It provides a source of water and nutrients, as well as a moderate temperature.[2] Resident microbes of the mouth adhere to the teeth and gums to resist mechanical flushing from the mouth to stomach where acid-sensitive microbes are destroyed by hydrochloric acid.[2][3]

Anaerobic bacteria in the oral cavity include: Actinomyces, Arachnia, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, Fusobacterium, Lactobacillus, Leptotrichia, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Propionibacterium, Selenomonas, Treponema, and Veillonella.[4] In addition, there are also a number of fungi found in the oral cavity, including: Candida, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Glomus, Alternaria, Penicillium, and Cryptococcus.[11] The oral cavity of a new-born baby does not contain bacteria but rapidly becomes colonized with bacteria such as Streptococcus salivarius. With the appearance of the teeth during the first year colonization by Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis occurs as these organisms colonise the dental surface and gingiva. Other strains of streptococci adhere strongly to the gums and cheeks but not to the teeth. The gingival crevice area (supporting structures of the teeth) provides a habitat for a variety of anaerobic species. Bacteroides and spirochetes colonize the mouth around puberty.[7]

Ecological sites for oral microbiota

[edit]As a diverse environment, a variety of organisms can inhabit unique ecological niches present in the oral cavity including the teeth, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, and palates.[12]

Dental plaque

[edit]The dental plaque is made up of the microbial community that is adhered to the tooth surface; this plaque is also recognized as a biofilm. While it is said that this plaque is adhered to the tooth surface, the microbial community of the plaque is not directly in contact with the enamel of the tooth. Instead, bacteria with the ability to form attachments to the acquired pellicle, which contains certain salivary proteins, on the surface of the teeth, begin the establishment of the biofilm. Upon dental plaque maturation, in which the microbial community grows and diversifies, the plaque is covered in an interbacterial matrix.[8]

Dental calculus

[edit]The calculus of the oral cavity is the result of mineralization of and around dead microorganisms; this calculus can then be colonized by living bacteria. Dental calculus can be present on supragingival and subgingival surfaces.[8]

Oral mucosa

[edit]The mucosa of the oral cavity provides a unique ecological site for microbiota to inhabit. Unlike the teeth, the mucosa of the oral cavity is frequently shedding and thus its microbial inhabitants are both kept at lower relative abundance than those of the teeth but also must be able to overcome the obstacle of the shedding epithelia.[8]

Tongue

[edit]Unlike other mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity, the nature of the top surface of the tongue, due in part to the presence of numerous papillae, provides a unique ecological niche for its microbial inhabits. One important characteristic of this habitat is that the spaces between the papillae tend to not receive much, if any, oxygenated saliva, which creates an environment suitable for microaerophilic and obligate anaerobic microbiota.[13]

Acquisition of oral microbiota

[edit]Acquisition of the oral microbiota heavily depends on the route of delivery as an infant – vaginal versus caesarian; upon comparing infants three months after birth, infants born vaginally were reported to have higher oral taxonomic diversity than their cesarean-born counterparts.[14][12] Further acquisition is determined by diet, developmental accomplishments, general lifestyle habits, hygiene, and the use of antibiotics.[14] Breastfed infants are noted to have higher oral lactobacilli colonization than their formula-fed counterparts.[12] Diversity of the oral microbiome is also shown to flourish upon the eruption of primary teeth and later adult teeth, as new ecological niches are introduced to the oral cavity.[12][14]

Factors of microbial colonization

[edit]Saliva plays a considerable role in influencing the oral microbiome.[15] More than 800 species of bacteria colonize oral mucus, 1,300 species are found in the gingival crevice, and nearly 1,000 species comprise dental plaque. The mouth is a rich environment for hundreds of species of bacteria since saliva is mostly water and plenty of nutrients pass through the mouth each day. When kissing, it takes only 10 seconds for no less than 80 million bacteria to be exchanged by the passing of saliva. However, the effect is transitory, as each individual quickly returns to their own equilibrium.[16][17]

Due to progress in molecular biology techniques, scientific understanding of oral ecology is improving. Oral ecology is being more comprehensively mapped, including the tongue, the teeth, the gums, salivary glands, etc. which are home to these communities of different microorganisms.[18]

The host's immune system controls the bacterial colonization of the mouth and prevents local infection of tissues. A dynamic equilibrium exists notably between the bacteria of dental plaque and the host's immune system, enabling the plaque to stay behind in the mouth when other biofilms are washed away.[19]

In equilibrium, the bacterial biofilm produced by the fermentation of sugar in the mouth is quickly swept away by the saliva, except for dental plaque. In cases of imbalance in the equilibrium, oral microorganisms grow out of control and cause oral diseases such as tooth decay and periodontal disease. Several studies have also linked poor oral hygiene to infection by pathogenic bacteria.[20]

Role in health

[edit]The oral microbiota is largely related to systemic health, and disturbances in the oral microbiota can lead to diseases in both the oral cavity and the rest of the body.[21] There are many factors that influence the diversity of the oral microbiota, such as age, diet, hygiene practices, and genetics.[22]

Of particular interest is the role of oral microorganisms in the two major dental diseases: dental caries and periodontal disease.[7] There are many factors of oral health which need to be preserved in order to prevent pathogenesis of the oral microbiota or diseases of the mouth. Dental plaque is the material that adheres to the teeth and consists of bacterial cells (mainly S. mutans and S. sanguis), salivary polymers and bacterial extracellular products. Plaque is a biofilm on the surfaces of the teeth. This accumulation of microorganisms subject the teeth and gingival tissues to high concentrations of bacterial metabolites which results in dental disease. If not taken care of, via brushing or flossing, the plaque can turn into tartar (its hardened form) and lead to gingivitis or periodontal disease. In the case of dental cavities, proteins involved in colonization of teeth by Streptococcus mutans can produce antibodies that inhibit the cariogenic process which can be used to create vaccines.[19]

Bacteria species typically associated with the oral microbiota have been found to be present in women with bacterial vaginosis.[23] Genera of fungi that are frequently found in the mouth include Candida, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Glomus, Alternaria, Penicillium, and Cryptococcus, among others.[6]

Additionally, research has correlated poor oral health and the resulting ability of the oral microbiota to invade the body to affect cardiac health as well as cognitive function.[20] High levels of circulating antibodies to oral pathogens Campylobacter rectus, Veillonella parvula and Prevotella melaninogenica are associated with hypertension in human.[24]

Importance of dental hygiene

[edit]One of the most important factors in promoting optimal oral microbiota health is the use of good oral hygiene practices. To prevent any possible complication from an altered oral microbiota, it is important to brush and floss every day, schedule regular cleanings, eat a healthy diet, and replace toothbrushes frequently.[25] Dental plaque is associated with two extremely common oral diseases, dental caries and periodontal disease.[26] Consistent toothbrushing and flossing is essential for disrupting harmful plaque formation. Research has shown that flossing is associated with a decrease in the bacteria Streptococcus mutans which has been shown to be involved in cavity formation.[27] Insufficient brushing and flossing can lead to gum and tooth disease, and eventually tooth loss.[25]

In addition, poor dental hygiene has been linked to conditions such as osteoporosis, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.[25]

Issues and areas of research

[edit]The oral environment (temperature, humidity, pH, nutrients, etc.) impacts the selection of adapted (and sometimes pathogenic) populations of microorganisms.[28] For a young person or an adult in good health and with a healthy diet, the microbes living in the mouth adhere to mucus, teeth and gums to resist removal by saliva. Eventually, they are mostly washed away and destroyed during their trip through the stomach.[28][29] Salivary flow and oral conditions vary person-to-person, and also relative to the time of day and whether or not an individual sleeps with their mouth open. From youth to old age, the entire mouth interacts with and affects the oral microbiome.[30] Via the larynx, numerous bacteria can travel through the respiratory tract to the lungs. There, mucus is charged with their removal. Pathogenic oral microflora have been linked to the production of factors which favor autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and arthritis, as well as cancers of the colon, lungs and breasts.[31]

Intercellular communication

[edit]Most of the bacterial species found in the mouth belong to microbial communities, called biofilms, a feature of which is inter-bacterial communication. Cell–cell contact is mediated by specific protein adhesins and often, as in the case of inter-species aggregation, by complementary polysaccharide receptors. Another method of communication involves cell–cell signalling molecules, which are of two classes: those used for intra-species and those used for inter-species signalling. An example of intra-species communication is quorum sensing. Oral bacteria have been shown to produce small peptides, such as competence stimulating peptides, which can help promote single-species biofilm formation. A common form of inter-species signalling is mediated by 4, 5-dihydroxy-2, 3-pentanedione (DPD), also known as autoinducer-2 (Al-2).[32]

Evolution

[edit]The evolution of the human oral microbiome can be traced through time via the sequencing of dental calculus (essentially fossilized dental plaque).[33]

As mentioned in prior sections, the human oral microbiome has important implications for the health and wellness of human beings overall, and is often the only surviving health record for ancient populations.

The oral microbiome has evolved over time alongside humans, in response to changes in diet, lifestyle, environment, and even the advent of cooking.[33] There have also been similarities in oral microbiota across hominins, as well as other primate species. While a core microbiome consisting of specific bacteria exists across most individuals, significant variation can arise depending on an individual’s unique environment, lifestyle, physiology, and heritage.[34]

Considering that oral bacteria are transferred vertically from primary caregivers in early childhood, and horizontally between family members later in life, archaeological dental calculus is a unique way to trace population structure, movement, and admixture between ancient cultures, as well as the spread of disease.[33]

Pre-Mesolithic

[edit]Relationship to primates

[edit]Ancient humans are thought to have maintained a much different oral microbiome landscape than non-human primates, despite having a shared environment. Existing data has found that chimpanzees maintain higher levels of Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria, while humans have greater proportions of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria.[33] Human oral microbiota have also been found to be less diverse when compared with other primates.[33]

Relationship to hominins

[edit]Of the hominins (Homo erectus, Neanderthals, Denisovans) Neanderthal oral microbiomes have been studied in the greatest detail. A cluster of oral microbiota has been found to be shared across Spanish Neanderthals, foraging humans from ~3000 years ago, and a single wild-caught chimpanzee. Similarities have also been found between a meat-eating Neanderthal in Belgium, and hunter humans in Europe and Africa. Ozga et al. (2019) found that Neanderthals and humans share similar oral microbiota, and are more alike to each other than to chimpanzees. Weyrich (2021) finds that these observations suggest humans shared an oral microbiota with Neanderthals until at least 3000 years ago. While it is possible that humans and Neanderthals shared oral microbiota from the moment of separation (~700,000 years ago) until their extinction, Weyrich finds that an equally likely hypothesis is that convergent evolution accounted for similar oral microbiotas across Neanderthals and humans for that period.[35]

Major shifts through archaeological periods

[edit]The human oral microbiome has been a subject of increasing scientific scrutiny, especially in understanding its evolutionary journey. The oral microbiome has undergone significant shifts in composition, particularly during key historical periods like the Neolithic and the Industrial Revolution.

The Neolithic revolution: a turning point

[edit]The Neolithic period began around 10,000 years ago and marked a significant turning point in human history. This era saw the shift from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture and farming. One of the most significant changes during this period was the adoption of carbohydrate-rich diets, particularly the consumption of domesticated cereals like wheat and barley. This shift had a profound impact on the oral microbiome. The increase in fermentable carbohydrates led to a surge in dental caries, a common oral health issue. Additionally, the Neolithic period also witnessed a reduction in microbial diversity in the oral environment.[33]

The Medieval period: a period of stability

[edit]Transitioning from the Neolithic to the Medieval period, which began around 400 years ago, there was little change in the composition of the oral microbiota. This period of stability suggests that despite advancements in agriculture and societal structures, the oral microbiome remained relatively constant. This period did not bring about significant shifts in oral microbial communities, indicating a sort of equilibrium had been reached.[33]

The Industrial Revolution: a modern dilemma

[edit]The Industrial Revolution, starting around 1850, brought about another significant shift in human lifestyle and, consequently, the oral microbiome. The widespread availability of industrially processed flour and sugar led to a predominance of cariogenic bacteria in the oral environment. This shift has persisted to the present day, making the modern oral microbiome less diverse than ever before, rendering it less resilient to perturbations in the form of dietary imbalances or invasion by pathogenic bacterial species.[33]

Implications for modern health

[edit]The shifts in the oral microbiome through time have significant implications for modern health. The current lack of diversity in the oral microbiome makes it more susceptible to imbalances and pathogenic invasions. This, in turn, can lead to a range of oral and systemic health issues, from dental caries to cardiovascular disease. Dental caries affects between 60 and 90% of children and adults in industrialized countries, and has a more severe effect on less industrialized countries with less capable healthcare systems.[36] An understanding of the oral microbiome, via an examination of the evolution of the oral microbiome, can help science understand past errors and help inform the best path forward in sustainable healthcare interventions that work proactively with the body's natural systems, rather than fighting them with intermittent reactive interventions.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schwiertz A (2016). Microbiota of the human body : implications in health and disease. Switzerland: Springer. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-319-31248-4.

- ^ a b c d Sherwood L, Willey J, Woolverton C (2013). Prescott's Microbiology (9th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 713–721. ISBN 9780073402406. OCLC 886600661.

- ^ a b Wang ZK, Yang YS, Stefka AT, Sun G, Peng LH (April 2014). "Review article: fungal microbiota and digestive diseases". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 39 (8): 751–766. doi:10.1111/apt.12665. PMID 24612332. S2CID 22101484.

In addition, GI fungal infection is reported even among those patients with normal immune status. Digestive system-related fungal infections may be induced by both commensal opportunistic fungi and exogenous pathogenic fungi. ... Candida sp. is also the most frequently identified species among patients with gastric IFI. ... It was once believed that gastric acid could kill microbes entering the stomach and that the unique ecological environment of the stomach was not suitable for microbial colonisation or infection. However, several studies using culture-independent methods confirmed that large numbers of acid-resistant bacteria belonging to eight phyla and up to 120 species exist in the stomach, such as Streptococcus sp., Neisseria sp. and Lactobacillus sp. etc.26, 27 Furthermore, Candida albicans can grow well in highly acidic environments,28 and some genotypes may increase the severity of gastric mucosal lesions.29

- ^ a b Sutter VL (1984). "Anaerobes as normal oral flora". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 6 (Suppl 1): S62 – S66. doi:10.1093/clinids/6.Supplement_1.S62. PMID 6372039.

- ^ Deo PN, Deshmukh R (2019). "Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 23 (1): 122–128. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18. PMC 6503789. PMID 31110428.

- ^ a b Cui L, Morris A, Ghedin E (July 2013). "The human mycobiome in health and disease". Genome Medicine. 5 (7): 63. doi:10.1186/gm467. PMC 3978422. PMID 23899327. Figure 2: Distribution of fungal genera in different body sites

- ^ a b c d e Rogers AH, ed. (2008). Molecular Oral Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-24-0.

- ^ a b c d e Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G, Jenkinson HF (2014). Oral microbiology and immunology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-673-5. OCLC 840878148.

- ^ Pinto, Rita Del; Ferri, Claudio; Giannoni, Mario; Cominelli, Fabio; Pizarro, Theresa T.; Pietropaoli, Davide (2024-09-10). "Meta-analysis of oral microbiome reveals sex-based diversity in biofilms during periodontitis". JCI Insight. 9 (17). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.171311. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 11385077. PMID 39253976.

- ^ Dorfman J. "The Center for Special Dentistry".

- ^ Cui L, Morris A, Ghedin E (2013). "The human mycobiome in health and disease". Genome Medicine. 5 (7): 63. doi:10.1186/gm467. PMC 3978422. PMID 23899327.

- ^ a b c d Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, Marsh PD, Meuric V, Pedersen AM, et al. (November 2016). "The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals". British Dental Journal. 221 (10): 657–666. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.865. hdl:10722/239520. PMID 27857087. S2CID 3732555.

- ^ Wilson M (2005). Microbial inhabitants of humans : their ecology and role in health and disease. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84158-5. OCLC 54931635.

- ^ a b c Marchesi JR, ed. (2014). The human microbiota and microbiome. Wallingford: CABI. doi:10.1079/9781780640495.0000. ISBN 978-1-78064-049-5.

- ^ Marsh PD, Do T, Beighton D, Devine DA (February 2016). "Influence of saliva on the oral microbiota". Periodontology 2000. 70 (1): 80–92. doi:10.1111/prd.12098. PMID 26662484.

- ^ Bertrand M (2009-11-26). "DUHL Olga Anna (dir.), Amour, sexualité et médecine aux XVe et XVIe siècles, Dijon, Editions Universitaires de Dijon, 2009". Genre, Sexualité & Société (2). doi:10.4000/gss.1001. ISSN 2104-3736.

- ^ Kort R, Caspers M, van de Graaf A, van Egmond W, Keijser B, Roeselers G (December 2014). "Shaping the oral microbiota through intimate kissing". Microbiome. 2 (1) 41. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-2-41. PMC 4233210. PMID 25408893.

- ^ Attar N (March 2016). "Microbial ecology: FISHing in the oral microbiota". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 14 (3): 132–133. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.21. PMID 26853115. S2CID 31853510.

- ^ a b Rogers AH (2008). Molecular Oral Microbiology. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press. ISBN 9781904455240. OCLC 170922278.

- ^ a b Noble JM, Scarmeas N, Papapanou PN (October 2013). "Poor oral health as a chronic, potentially modifiable dementia risk factor: review of the literature". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 13 (10) 384. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0384-x. PMC 6526728. PMID 23963608.

- ^ Gao, Lu (7 May 2018). "Oral microbiomes: more and more importance in oral cavity and whole body". Protein and Cell. 9 (5): 488–500. doi:10.1007/s13238-018-0548-1. PMC 5960472. PMID 29736705.

- ^ Sedghi, DiMassa (31 August 2021). "The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease". Periodontology 2000. 87 (1): 107–131. doi:10.1111/prd.12393. PMC 8457218. PMID 34463991.

- ^ Africa CW, Nel J, Stemmet M (July 2014). "Anaerobes and bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: virulence factors contributing to vaginal colonisation". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (7): 6979–7000. doi:10.3390/ijerph110706979. PMC 4113856. PMID 25014248.

- ^ Pietropaoli D, Del Pinto R, Ferri C, Ortu E, Monaco A (August 2019). "Definition of hypertension-associated oral pathogens in NHANES". Journal of Periodontology. 90 (8): 866–876. doi:10.1002/JPER.19-0046. PMID 31090063. S2CID 155089995.

- ^ a b c "Oral health: A window to your overall health". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- ^ Marsh, PD (1 September 1995). "Dental plaque as a biofilm". Journal of Industrial Microbiology. 15 (3): 169–175. doi:10.1007/BF01569822. PMID 8519474.

- ^ Burcham, Zachary (7 February 2020). "Patterns of Oral Microbiota Diversity in Adults and Children: A Crowdsourced Population Study". Scientific Reports. 10 (1) 2133. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.2133B. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59016-0. PMC 7005749. PMID 32034250.

- ^ a b Linda Sherwood, Joanne Willey and Christopher Woolverton, New York, McGraw Hill, 2013, 9th ed., p. 713–721

- ^ Wang ZK, Yang YS, Stefka AT, Sun G, Peng LH (April 2014). "Review article: fungal microbiota and digestive diseases". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 39 (8): 751–766. doi:10.1111/apt.12665. PMID 24612332. S2CID 22101484.

- ^ Hultberg B, Lundblad A, Masson PK, Ockerman PA (November 1975). "Specificity studies on alpha-mannosidases using oligosaccharides from mannosidosis urine as substrates". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Enzymology. 410 (1): 156–163. doi:10.1016/0005-2744(75)90216-8. PMID 70.

- ^ Fleming C (2016). Microbiota activated CD103 DCS stemming from oral microbiota adaptation specifically drive T17 proliferation and activation (PDF) (Thesis). University of Louisville. doi:10.18297/etd/2445.

- ^ Rickard AH (2008). "Cell-cell Communication in Oral Microbial Communities". Molecular Oral Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-24-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Adler, Christina J.; Dobney, Keith; Weyrich, Laura S.; Kaidonis, John; Walker, Alan W.; Haak, Wolfgang; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Townsend, Grant; Sołtysiak, Arkadiusz; Alt, Kurt W.; Parkhill, Julian; Cooper, Alan (April 2013). "Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions". Nature Genetics. 45 (4): 450–455, 455e1. doi:10.1038/ng.2536. ISSN 1546-1718. PMC 3996550. PMID 23416520.

- ^ a b Gancz, Abigail S.; Weyrich, Laura S. (2023). "Studying ancient human oral microbiomes could yield insights into the evolutionary history of noncommunicable diseases". F1000Research. 12: 109. doi:10.12688/f1000research.129036.2. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 10090864. PMID 37065506.

- ^ Weyrich, Laura S. (February 2021). "The evolutionary history of the human oral microbiota and its implications for modern health". Periodontology 2000. 85 (1): 90–100. doi:10.1111/prd.12353. ISSN 1600-0757. PMID 33226710. S2CID 227132686.

- ^ Baker, Jonathon L.; Edlund, Anna (2019). "Exploiting the Oral Microbiome to Prevent Tooth Decay: Has Evolution Already Provided the Best Tools?". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 3323. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03323. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 6338091. PMID 30687294.