Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Microbial loop

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

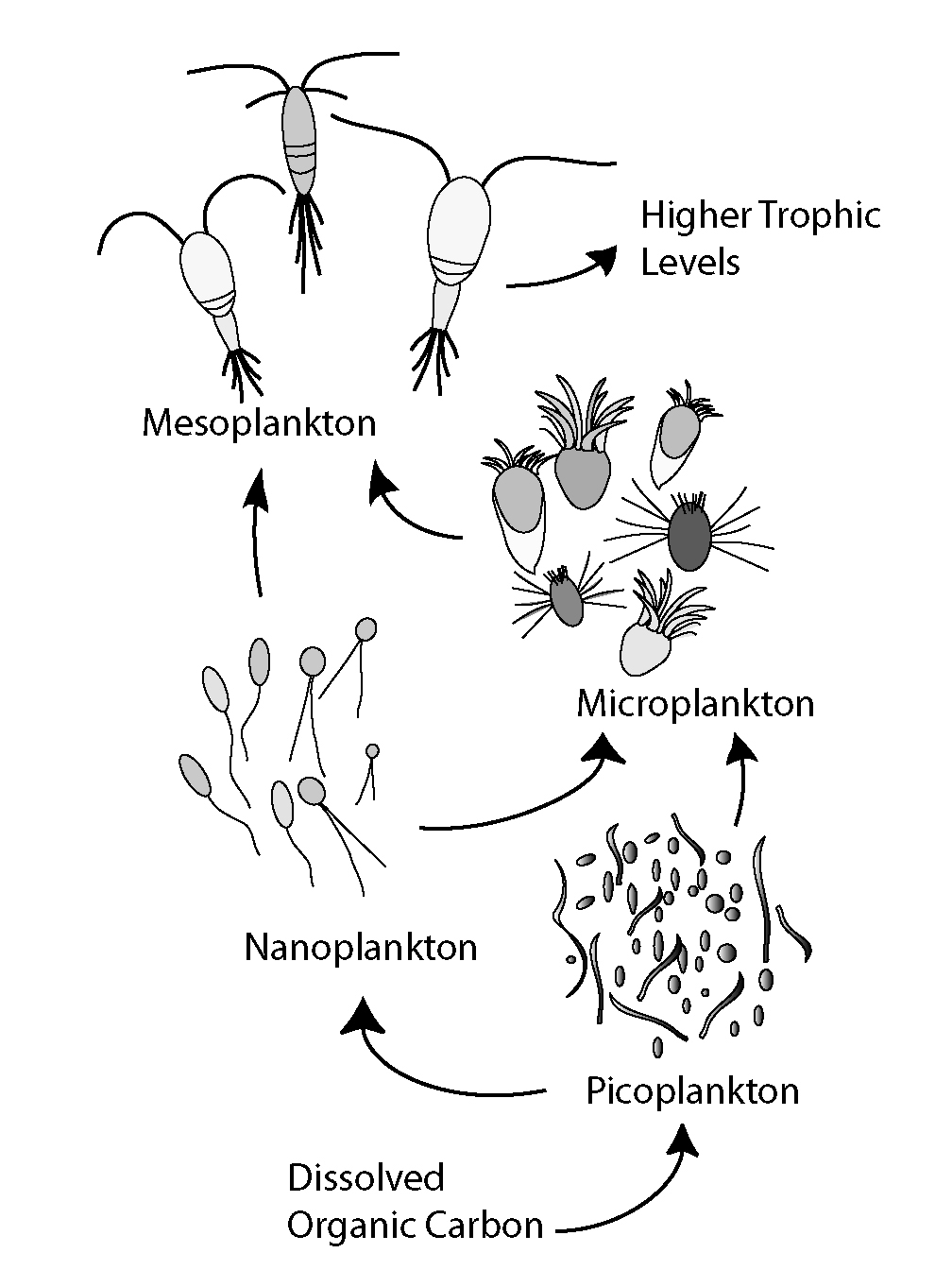

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by phytoplankton-zooplankton-nekton. In soil systems, the microbial loop refers to soil carbon. The term microbial loop was coined by Farooq Azam, Tom Fenchel et al.[1] in 1983 to include the role played by bacteria in the carbon and nutrient cycles of the marine environment.

In general, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is introduced into the ocean environment from bacterial lysis, the leakage or exudation of fixed carbon from phytoplankton (e.g., mucilaginous exopolymer from diatoms), sudden cell senescence, sloppy feeding by zooplankton, the excretion of waste products by aquatic animals, or the breakdown or dissolution of organic particles from terrestrial plants and soils.[2] Bacteria in the microbial loop decompose this particulate detritus to utilize this energy-rich matter for growth. Since more than 95% of organic matter in marine ecosystems consists of polymeric, high-molecular- weight (HMW) compounds (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides, lipids), only a small portion of total dissolved organic matter (DOM) is readily utilizable to most marine organisms at higher trophic levels. This means that dissolved organic carbon is not available directly to most marine organisms; marine bacteria introduce this organic carbon into the food web, resulting in additional energy becoming available to higher trophic levels. Recently the term "microbial food web" has been substituted for the term "microbial loop".

History

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Carbon cycle |

|---|

|

Prior to the discovery of the microbial loop, the classic view of marine food webs was one of a linear chain from phytoplankton to nekton. Generally, marine bacteria were not thought to be significant consumers of organic matter (including carbon), although they were known to exist. However, the view of a marine pelagic food web was challenged during the 1970s and 1980s by Pomeroy and Azam, who suggested the alternative pathway of carbon flow from bacteria to protozoans to metazoans.[3][1]

Early work in marine ecology that investigated the role of bacteria in oceanic environments concluded their role to be very minimal. Traditional methods of counting bacteria (e.g., culturing on agar plates) only yielded small numbers of bacteria that were much smaller than their true ambient abundance in seawater. Developments in technology for counting bacteria have led to an understanding of the significant importance of marine bacteria in oceanic environments.

In the 1970s, the alternative technique of direct microscopic counting was developed by Francisco et al. (1973) and Hobbie et al. (1977). Bacterial cells were counted with an epifluorescence microscope, producing what is called an "acridine orange direct count" (AODC). This led to a reassessment of the large concentration of bacteria in seawater, which was found to be more than was expected (typically on the order of 1 million per milliliter). Also, development of the "bacterial productivity assay" showed that a large fraction (i.e. 50%) of net primary production (NPP) was processed by marine bacteria.

In 1974, Larry Pomeroy published a paper in BioScience entitled "The Ocean's Food Web: A Changing Paradigm", where the key role of microbes in ocean productivity was highlighted.[3] In the early 1980s, Azam and a panel of top ocean scientists published the synthesis of their discussion in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series entitled "The Ecological Role of Water Column Microbes in the Sea". The term 'microbial loop' was introduced in this paper, which noted that the bacteria-consuming protists were in the same size class as phytoplankton and likely an important component of the diet of planktonic crustaceans.[1]

Evidence accumulated since this time has indicated that some of these bacterivorous protists (such as ciliates) are actually selectively preyed upon by these copepods. In 1986, Prochlorococcus, which is found in high abundance in oligotrophic areas of the ocean, was discovered by Sallie W. Chisholm, Robert J. Olson, and other collaborators (although there had been several earlier records of very small cyanobacteria containing chlorophyll b in the ocean[4][5] Prochlorococcus was discovered in 1986[6]).[7] Stemming from this discovery, researchers observed the changing role of marine bacteria along a nutrient gradient from eutrophic to oligotrophic areas in the ocean.

Factors controlling the microbial loop

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Biogeochemical cycles |

|---|

|

The efficiency of the microbial loop is determined by the density of marine bacteria within it.[8] It has become clear that bacterial density is mainly controlled by the grazing activity of small protozoans such as various taxonomic groups of flagellates. Also, viral infection causes bacterial lysis, which release cell contents back into the dissolved organic matter (DOM) pool, lowering the overall efficiency of the microbial loop. Mortality from viral infection has almost the same magnitude as that from protozoan grazing. However, compared to protozoan grazing, the effect of viral lysis can be very different because lysis is highly host-specific to each marine bacteria. Both protozoan grazing and viral infection balance the major fraction of bacterial growth. In addition, the microbial loop dominates in oligotrophic waters, rather than in eutrophic areas - there the classical plankton food chain predominates, due to the frequent fresh supply of mineral nutrients (e.g. spring bloom in temperate waters, upwelling areas). The magnitude of the efficiency of the microbial loop can be determined by measuring bacterial incorporation of radiolabeled substrates (such as tritiated thymidine or leucine).

In marine ecosystems

[edit]The microbial loop is of particular importance in increasing the efficiency of the marine food web via the utilization of dissolved organic matter (DOM), which is typically unavailable to most marine organisms. In this sense, the process aids in recycling of organic matter and nutrients and mediates the transfer of energy above the thermocline. More than 30% of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) incorporated into bacteria is respired and released as carbon dioxide. The other main effect of the microbial loop in the water column is that it accelerates mineralization through regenerating production in nutrient-limited environments (e.g. oligotrophic waters). In general, the entire microbial loop is to some extent typically five to ten times the mass of all multicellular marine organisms in the marine ecosystem. Marine bacteria are the base of the food web in most oceanic environments, and they improve the trophic efficiency of both marine food webs and important aquatic processes (such as the productivity of fisheries and the amount of carbon exported to the ocean floor). Therefore, the microbial loop, together with primary production, controls the productivity of marine systems in the ocean.

Many planktonic bacteria are motile, using a flagellum to propagate, and chemotax to locate, move toward, and attach to a point source of dissolved organic matter (DOM) where fast growing cells digest all or part of the particle. Accumulation within just a few minutes at such patches is directly observable. Therefore, the water column can be considered to some extent as a spatially organized place on a small scale rather than a completely mixed system. This patch formation affects the biologically-mediated transfer of matter and energy in the microbial loop.

More currently, the microbial loop is considered to be more extended.[9] Chemical compounds in typical bacteria (such as DNA, lipids, sugars, etc.) and similar values of C:N ratios per particle are found in the microparticles formed abiotically. Microparticles are a potentially attractive food source to bacterivorous plankton. If this is the case, the microbial loop can be extended by the pathway of direct transfer of dissolved organic matter (DOM) via abiotic microparticle formation to higher trophic levels. This has ecological importance in two ways. First, it occurs without carbon loss, and makes organic matter more efficiently available to phagotrophic organisms, rather than only heterotrophic bacteria. Furthermore, abiotic transformation in the extended microbial loop depends only on temperature and the capacity of DOM to aggregate, while biotic transformation is dependent on its biological availability.[9]

In land ecosystems

[edit]

Soil ecosystems are highly complex and subject to different landscape-scale perturbations that govern whether soil carbon is retained or released to the atmosphere.[11] The ultimate fate of soil organic carbon is a function of the combined activities of plants and below ground organisms, including soil microbes. Although soil microorganisms are known to support a plethora of biogeochemical functions related to carbon cycling,[12] the vast majority of the soil microbiome remains uncultivated and has largely cryptic functions.[13] Only a mere fraction of soil microbial life has been catalogued to date, although new soil microbes [13] and viruses are increasingly being discovered.[14] This lack of knowledge results in uncertainty of the contribution of soil microorganisms to soil organic carbon cycling and hinders construction of accurate predictive models for global carbon flux under climate change.[15][10]

The lack of information concerning the soil microbiome metabolic potential makes it particularly challenging to accurately account for the shifts in microbial activities that occur in response to environmental change. For example, plant-derived carbon inputs can prime microbial activity to decompose existing soil organic carbon at rates higher than model expectations, resulting in error within predictive models of carbon fluxes.[16][10]

To account for this, a conceptual model known as the microbial carbon pump, illustrated in the diagram on the right, has been developed to define how soil microorganisms transform and stabilise soil organic matter.[17] As shown in the diagram, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is fixed by plants (or autotrophic microorganisms) and added to soil through processes such as (1) root exudation of low-molecular weight simple carbon compounds, or deposition of leaf and root litter leading to accumulation of complex plant polysaccharides. (2) Through these processes, carbon is made bioavailable to the microbial metabolic "factory" and subsequently is either (3) respired to the atmosphere or (4) enters the stable carbon pool as microbial necromass. The exact balance of carbon efflux versus persistence is a function of several factors, including aboveground plant community composition and root exudate profiles, environmental variables, and collective microbial phenotypes (i.e., the metaphenome).[18][10]

In this model, microbial metabolic activities for carbon turnover are segregated into two categories: ex vivo modification, referring to transformation of plant-derived carbon by extracellular enzymes, and in vivo turnover, for intracellular carbon used in microbial biomass turnover or deposited as dead microbial biomass, referred to as necromass. The contrasting impacts of catabolic activities that release soil organic carbon as carbon dioxide (CO2), versus anabolic pathways that produce stable carbon compounds, control net carbon retention rates. In particular, microbial carbon sequestration represents an underrepresented aspect of soil carbon flux that the microbial carbon pump model attempts to address.[17] A related area of uncertainty is how the type of plant-derived carbon enhances microbial soil organic carbon storage or alternatively accelerates soil organic carbon decomposition.[19] For example, leaf litter and needle litter serve as sources of carbon for microbial growth in forest soils, but litter chemistry and pH varies by vegetation type [e.g., between root and foliar litter [20] or between deciduous and coniferous forest litter (14)]. In turn, these biochemical differences influence soil organic carbon levels through changing decomposition dynamics.[21] Also, increased diversity of plant communities increases rates of rhizodeposition, stimulating microbial activity and soil organic carbon storage,[22] although soils eventually reach a saturation point beyond which they cannot store additional carbon.[23][10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Azam, Farooq; Fenchel, Tom; Field, J.G.; Gray, J.S.; Meyer-Reil, L.A.; Thingstad, F. (1983). "The Ecological Role of Water-Column Microbes in the Sea". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 10: 257–263. Bibcode:1983MEPS...10..257A. doi:10.3354/meps010257.

- ^ Van den Meersche, Karel; Middelburg, Jack J.; Soetaert, Karline; van Rijswijk, Pieter; Boschker, Henricus T. S.; Heip, Carlo H. R. (2004). "Carbon-nitrogen coupling and algal-bacterial interactions during an experimental bloom: Modeling a13C tracer experiment". Limnology and Oceanography. 49 (3): 862–878. Bibcode:2004LimOc..49..862V. doi:10.4319/lo.2004.49.3.0862. hdl:1854/LU-434810. ISSN 0024-3590.

- ^ a b Pomeroy, Lawrence R. (1974). "The Ocean's Food Web, A Changing Paradigm". BioScience. 24 (9): 499–504. doi:10.2307/1296885. ISSN 0006-3568. JSTOR 1296885.

- ^ Johnson, P. W.; Sieburth, J. M. (1979). "Chroococcoid cyanobacteria in the sea: a ubiquitous and diverse phototrophic biomass". Limnology and Oceanography. 24 (5): 928–935. Bibcode:1979LimOc..24..928J. doi:10.4319/lo.1979.24.5.0928.

- ^ Gieskes, W. W. C.; Kraay, G. W. (1983). "Unknown chlorophyll a derivatives in the North Sea and the tropical Atlantic Ocean revealed by HPLC analysis". Limnology and Oceanography. 28 (4): 757–766. Bibcode:1983LimOc..28..757G. doi:10.4319/lo.1983.28.4.0757.

- ^ Chisholm, S. W.; Olson, R. J.; Zettler, E. R.; Waterbury, J.; Goericke, R.; Welschmeyer, N. (1988). "A novel free-living prochlorophyte occurs at high cell concentrations in the oceanic euphotic zone". Nature. 334 (6180): 340–343. Bibcode:1988Natur.334..340C. doi:10.1038/334340a0. S2CID 4373102.

- ^ Chisholm, Sallie W.; Frankel, Sheila L.; Goericke, Ralf; Olson, Robert J.; Palenik, Brian; Waterbury, John B.; West-Johnsrud, Lisa; Zettler, Erik R. (1992). "Prochlorococcus marinus nov. gen. nov. sp.: an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b". Archives of Microbiology. 157 (3): 297–300. doi:10.1007/bf00245165. ISSN 0302-8933. S2CID 32682912.

- ^ Taylor, AH; Joint, I (1990). "A steady-state analysis of the 'microbial loop' in stratified systems". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 59. Inter-Research Science Center: 1–17. Bibcode:1990MEPS...59....1T. doi:10.3354/meps059001. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ^ a b Kerner, Martin; Hohenberg, Heinz; Ertl, Siegmund; Reckermann, Marcus; Spitzy, Alejandro (2003). "Self-organization of dissolved organic matter to micelle-like microparticles in river water". Nature. 422 (6928). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 150–154. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..150K. doi:10.1038/nature01469. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12634782. S2CID 4380194.

- ^ a b c d e Naylor, Dan; Sadler, Natalie; Bhattacharjee, Arunima; Graham, Emily B.; Anderton, Christopher R.; McClure, Ryan; Lipton, Mary; Hofmockel, Kirsten S.; Jansson, Janet K. (2020). "Soil Microbiomes Under Climate Change and Implications for Carbon Cycling". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45: 29–59. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-082720.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Jansson, Janet K.; Hofmockel, Kirsten S. (2020). "Soil microbiomes and climate change". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 18 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0265-7. OSTI 1615017. PMID 31586158. S2CID 203658781.

- ^ Thompson, Luke R.; et al. (2017). "A communal catalogue reveals Earth's multiscale microbial diversity". Nature. 551 (7681): 457–463. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..457T. doi:10.1038/nature24621. PMC 6192678. PMID 29088705.

- ^ a b Goel, Reeta; Kumar, Vinay; Suyal, Deep Chandra; Narayan; Soni, Ravindra (2018). "Toward the Unculturable Microbes for Sustainable Agricultural Production". Role of Rhizospheric Microbes in Soil. pp. 107–123. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8402-7_4. ISBN 978-981-10-8401-0.

- ^ Schulz, Frederik; Alteio, Lauren; Goudeau, Danielle; Ryan, Elizabeth M.; Yu, Feiqiao B.; Malmstrom, Rex R.; Blanchard, Jeffrey; Woyke, Tanja (2018). "Hidden diversity of soil giant viruses". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4881. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4881S. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07335-2. PMC 6243002. PMID 30451857.

- ^ Zeng, N.; Yoshikawa, C.; Weaver, A. J.; Strassmann, K.; Schnur, R.; Schnitzler, K.-G.; Roeckner, E.; Reick, C.; Rayner, P.; Raddatz, T.; Matthews, H. D.; Lindsay, K.; Knorr, W.; Kawamiya, M.; Kato, T.; Joos, F.; Jones, C.; John, J.; Bala, G.; Fung, I.; Eby, M.; Doney, S.; Cadule, P.; Brovkin, V.; von Bloh, W.; Bopp, L.; Betts, R.; Cox, P.; Friedlingstein, P. (2006). "Climate–Carbon Cycle Feedback Analysis: Results from the C4MIP Model Intercomparison". Journal of Climate. 19 (14): 3337–3353. Bibcode:2006JCli...19.3337F. doi:10.1175/JCLI3800.1. hdl:10036/68733.

- ^ Kuzyakov, Yakov; Horwath, William R.; Dorodnikov, Maxim; Blagodatskaya, Evgenia (2019). "Review and synthesis of the effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 on soil processes: No changes in pools, but increased fluxes and accelerated cycles". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 128: 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.10.005.

- ^ a b Liang, Chao; Schimel, Joshua P.; Jastrow, Julie D. (2017). "The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage". Nature Microbiology. 2 (8): 17105. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105. PMID 28741607. S2CID 9992380.

- ^ Bonkowski, Michael (2004). "Protozoa and plant growth: The microbial loop in soil revisited". New Phytologist. 162 (3): 617–631. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01066.x. PMID 33873756.

- ^ Sulman, Benjamin N.; Phillips, Richard P.; Oishi, A. Christopher; Shevliakova, Elena; Pacala, Stephen W. (2014). "Microbe-driven turnover offsets mineral-mediated storage of soil carbon under elevated CO2". Nature Climate Change. 4 (12): 1099–1102. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4.1099S. doi:10.1038/nclimate2436.

- ^ Harmon, Mark E.; Silver, Whendee L.; Fasth, Becky; Chen, HUA; Burke, Ingrid C.; Parton, William J.; Hart, Stephen C.; Currie, William S. (2009). "Long-term patterns of mass loss during the decomposition of leaf and fine root litter: An intersite comparison". Global Change Biology. 15 (5): 1320–1338. Bibcode:2009GCBio..15.1320H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01837.x. hdl:2027.42/74496.

- ^ Qualls, Robert (2016). "Long-Term (13 Years) Decomposition Rates of Forest Floor Organic Matter on Paired Coniferous and Deciduous Watersheds with Contrasting Temperature Regimes". Forests. 7 (12): 231. doi:10.3390/f7100231.

- ^ Lange, Markus; Eisenhauer, Nico; Sierra, Carlos A.; Bessler, Holger; Engels, Christoph; Griffiths, Robert I.; Mellado-Vázquez, Perla G.; Malik, Ashish A.; Roy, Jacques; Scheu, Stefan; Steinbeiss, Sibylle; Thomson, Bruce C.; Trumbore, Susan E.; Gleixner, Gerd (2015). "Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage" (PDF). Nature Communications. 6: 6707. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6707L. doi:10.1038/ncomms7707. PMID 25848862.

- ^ Stewart, Catherine E.; Paustian, Keith; Conant, Richard T.; Plante, Alain F.; Six, Johan (2007). "Soil carbon saturation: Concept, evidence and evaluation". Biogeochemistry. 86: 19–31. doi:10.1007/s10533-007-9140-0. S2CID 97153551.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fenchel, T. (1988) Marine Planktonic Food Chains. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics

- Fenchel, T. (2008) The microbial loop – 25 years later. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology

- Fuhrman, J.A., Azam, F. (1982) Thymidine incorporation as a measure of heterotrophic bacterioplankton production in marine surface waters. Marine Biology

- Kerner, M, Hohenberg, H., Ertl, S., Reckermannk, M., Spitzy, A. (2003) Self-organization of dissolved organic matter to micelle-like microparticles in river water. Nature

- Kirchman, D., Sigda, J., Kapuscinski, R., Mitchell, R. (1982) Statistical analysis of the direct count method for enumerating bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology

- Meinhard, S., Azam F. (1989) Protein content and protein synthesis rates of planktonic marine bacteria. Marine Ecology Progress Series

- Muenster, V.U. (1985) Investigations about structure, distribution and dynamics of different organic substrates in the DOM of Lake Plusssee. Hydrobiologie

- Pomeroy, L.R., Williams, P.J.leB., Azam, F. and Hobbie, J.E. (2007) "The microbial loop". Oceanography, 20(2): 28–33. doi:10.4319/lo.2004.49.3.0862.

- Stoderegger, K., Herndl, G.J. (1998) Production and Release of Bacterial Capsular Material and its Subsequent Utilization by Marine Bacterioplankton. Limnology & Oceanography