Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pointillism

View on Wikipedia

Pointillism (/ˈpwæ̃tɪlɪzəm/, also US: /ˈpwɑːn-ˌ ˈpɔɪn-/)[1] is a technique of painting in which small, distinct dots of color are applied in patterns to form an image.

Georges Seurat and Paul Signac developed the technique in 1886, branching from Impressionism. The term "Pointillism" was coined by art critics in the late 1880s to ridicule the works of these artists, but is now used without its earlier pejorative connotation.[2] The movement Seurat began with this technique is known as Neo-impressionism. The Divisionists used a similar technique of patterns to form images, though with larger cube-like brushstrokes.[3]

Technique

[edit]The technique relies on the ability of the eye and mind of the viewer to blend the color spots into a fuller range of tones. It is related to Divisionism, a more technical variant of the method. Divisionism is concerned with color theory, whereas pointillism is more focused on the specific style of brushwork used to apply the paint.[2] Pointillism is a technique with few serious practitioners today and is notably seen in the works of Seurat, Signac, and Cross.

From 1905 to 1907, Robert Delaunay and Jean Metzinger painted in a Divisionist style with large squares or 'cubes' of color: the size and direction of each gave a sense of rhythm to the painting, yet color varied independently of size and placement.[4] This form of Divisionism was a significant step beyond the preoccupations of Signac and Cross. In 1906, the art critic Louis Chassevent recognized the difference and, as art historian Daniel Robbins pointed out, used the word "cube" which would later be taken up by Louis Vauxcelles to baptize Cubism. Chassevent writes:

Practice

[edit]The practice of Pointillism is in sharp contrast to the traditional methods of blending pigments on a palette. Pointillism is analogous to the four-color CMYK printing process used by some color printers and large presses that place dots of cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black). Televisions and computer monitors use a similar technique to represent image colors using red, green and blue (RGB) colors.[9]

If red, blue, and green light (the additive primaries) are mixed, the result is something close to white light (see Prism (optics)). Painting is inherently subtractive, but Pointillist colors often seem brighter than typical mixed subtractive colors. This may be partly because subtractive mixing of the pigments is avoided, and because some of the white canvas may be showing between the applied dots.[9]

The painting technique used for Pointillist color mixing is at the expense of the traditional brushwork used to delineate texture.[9]

The majority of Pointillism is done in oil paint. Anything may be used in its place, but oils are preferred for their thickness and tendency not to run or bleed.[10]

Music

[edit]Pointillism also refers to a style of 20th-century music composition. Different musical notes are made in seclusion, rather than in a linear sequence, giving a sound texture similar to the painting version of Pointillism. This type of music is also known as punctualism or klangfarbenmelodie.

In the 21st century, Australian composer Georges Lentz’s music, influenced by the subtle dot paintings of Kathleen Petyarre and by the starry night sky in the Australian Outback, has also, in some aspects, been described as pointillistic[11].

Notable artists

[edit]

- Albert Dubois-Pillet

- Alfred William Finch

- Camille Pissarro

- Charles Angrand

- Chuck Close

- Gale D. Jones

- Georges Lemmen

- Georges Seurat

- Henri Delavallée

- Henri-Edmond Cross

- Hippolyte Petitjean

- Jan Toorop

- Jean Metzinger

- John Roy

- Louis Fabien (pseudonym)

- Maximilien Luce

- Paul Signac

- Théo van Rysselberghe

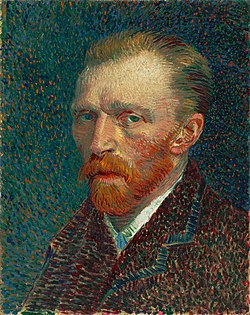

- Vincent van Gogh

Notable paintings

[edit]- A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat

- Bathers at Asnières by Georges Seurat

- The Windmills at Overschie by Paul Signac

- Banks of Seine by Georges Seurat

- A Coastal Scene by Théo van Rysselberghe

- Family in the Orchard by Théo van Rysselberghe

- Countryside at Noon by Théo van Rysselberghe

- Afternoon at Pardigon by Henri-Edmond Cross

- Rio San Trovaso, Venice by Henri-Edmond Cross

- The Seine in front of the Trocadero by Henri-Edmond Cross

- The Pine Tree at St. Tropez by Paul Signac

- Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890 by Paul Signac

- The Yellow Sail, Venice by Paul Signac

- Notre Dame Cathedral by Maximilien Luce

- Le Pont De Pierre, Rouen by Charles Angrand

- The Beach at Heist by Georges Lemmen

- Aline Marechal by Georges Lemmen

- Vase of Flowers by Georges Lemmen

- Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape by Jean Metzinger

Gallery

[edit]-

Georges Seurat, 1884–1886, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, oil on canvas, 207.6 x 308 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

-

Camille Pissarro, 1888, La Récolte des pommes, oil on canvas, 61 x 74 cm, Dallas Museum of Art

-

Jan Toorop, 1889, Bridge in London, Kröller-Müller Museum

-

Théo van Rysselberghe, 1899, His wife Maria and daughter Elisabeth

-

Paul Signac, 1901, L'Hirondelle Steamer on the Seine, oil on canvas, National Gallery in Prague

-

Henri-Edmond Cross, 1903-04, Regatta in Venice, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.7 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

Jean Metzinger, c.1906, Femme au Chapeau (Woman with a Hat), oil on canvas, 44.8 x 36.8 cm, Korban Art Foundation

-

Robert Delaunay, 1906, Portrait de Metzinger, oil on canvas, 55 x 43 cm

-

Hippolyte Petitjean, 1919, Femmes au bain, oil on canvas, 61.1 X 46 cm, private collection

-

Paul Signac, Femmes au Puits, 1892, showing a detail with constituent colors. Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Henri-Edmond Cross, L'air du soir, c.1893, Musée d'Orsay

See also

[edit]- Contemporary Indigenous Australian art, the most well-known style of which is known as "dot painting"

- Halftone

- Klangfarbenmelodie

- Micromontage, similar technique in music

- Pixel art

- Stipple engraving

References

[edit]- ^ "pointillism". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "Pointillism". www.artcyclopedia.com.

- ^ Ruhrberg, Karl. "Seurat and the Neo-Impressionists". Art of the 20th Century, Vol. 2. Koln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1998. ISBN 3-8228-4089-0.

- ^ Jean Metzinger, ca. 1907, quoted in Georges Desvallières, La Grande Revue, vol. 124, 1907, as cited in Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- ^ Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- ^ Louis Chassevent: Les Artistes indépendantes, 1906

- ^ Louis Chassevent, 22e Salon des Indépendants, 1906, Quelques petits salons, Paris, 1908, p. 32

- ^ Daniel Robbins, 1964, Albert Gleizes 1881 – 1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, Published by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, in collaboration with Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

- ^ a b c Vivien Greene, Divisionism, Neo-Impressionism: Arcadia & Anarchy, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2024 , ISBN 0-89207-357-8

- ^ "Nathan, Solon. "Pointillism Materials." Web. 9 Feb 2010". Archived from the original on 2009-10-19.

- ^ "The Music".

External links

[edit]- Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Signac, 1863–1935, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Exhibition catalogue, Dot Dot Dot ... Pointilism and Beyond 1885 - 2018, Jill Newhouse Gallery, 2 November - 10 December 2021

...