Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

French horn

View on WikipediaIt has been suggested that this article be merged into German horn. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2025. |

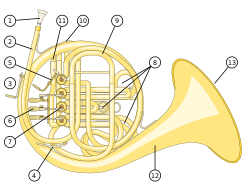

A modern double horn | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.232 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip vibration) |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| Builders | |

| More articles or information | |

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

The horn (the term French horn refers to horns with pistons, not with rotary valves) is a brass instrument made of tubing wrapped into a coil with a flared bell. The double horn in F/B♭ (technically a variety of German horn) is the horn most often used by players in professional orchestras and bands, although the descant and triple horn have become increasingly popular. A musician who plays a horn is known as a horn player or hornist.

Pitch is controlled through the combination of the following factors: speed of air through the instrument (controlled by the player's lungs and thoracic diaphragm); diameter and tension of lip aperture (by the player's lip muscles—the embouchure) in the mouthpiece; plus, in a modern horn, the operation of valves by the left hand, which route the air into extra sections of tubing. Most horns have lever-operated rotary valves, but some, especially older horns, use piston valves (similar to a trumpet's) and the Vienna horn uses double-piston valves, or pumpenvalves. The backward-facing orientation of the bell relates to the perceived desirability to create a subdued sound in concert situations, in contrast to the more piercing quality of the trumpet. A horn without valves is known as a natural horn, changing pitch along the natural harmonics of the instrument (similar to a bugle). Pitch may also be controlled by the position of the hand in the bell, in effect reducing the bell's diameter. The pitch of any note can easily be raised or lowered by adjusting the hand position in the bell.[2] The key of a natural horn can be changed by adding different crooks of different lengths.

Three valves control the flow of air in the single horn, which is tuned to F or less commonly B♭. The more common double horn has a fourth, trigger valve, usually operated by the thumb, which routes the air to one set of tubing tuned to F or another tuned to B♭ which expands the horn range to over four octaves and blends with flutes or clarinets in a woodwind ensemble. Triple horns with five valves are also made, usually tuned in F, B♭, and a descant E♭ or F. There are also double horns with five valves tuned in B♭, descant E♭ or F, and a stopping valve, which greatly simplifies the complicated and difficult hand-stopping technique,[3] though these are rarer. Also common are descant doubles, which typically provide B♭ and alto F branches.

A crucial element in playing the French horn deals with the mouthpiece. The mouthpiece is usually placed about 2⁄3 on the lips with more on the upper. Because of differences in the formation of the lips and teeth of different players, some tend to play with the mouthpiece slightly off center.[4] Although the exact side-to-side placement of the mouthpiece varies for most horn players, the up-and-down placement of the mouthpiece is generally two-thirds on the upper lip and one-third on the lower lip.[4] When playing higher notes, the majority of players exert a small degree of additional pressure on the lips using the mouthpiece. However, this is undesirable from the perspective of both endurance and tone: excessive mouthpiece pressure makes the horn sound forced and harsh and decreases the player's stamina due to the resulting constricted flow of blood to the lips and lip muscles. Added pressure from the lips to the mouthpiece can also result in tension in the face resulting in what brass players often call "pushing". As mentioned before, this results in an undesirable sound, and loss of stamina.[4]

Name

[edit]The name "French horn" first came into use in the late 17th century. At that time, French makers were preeminent in the manufacture of hunting horns and were credited with creating the now-familiar, circular "hoop" shape of the instrument. As a result, these instruments were often called, even in English, by their French names: trompe de chasse or cor de chasse (lit. 'trumpet of hunt' or 'horn of hunt'—the clear modern distinction between trompes [trumpets] and cors [horns] did not exist at that time).[5]

German makers first devised crooks to make such horns playable in different keys—so musicians came to use "French" and "German" to distinguish the simple hunting horn from the newer horn with crooks, which in England was also called the Italian name corno cromatico (chromatic horn).[5]

More recently, "French horn" is often used colloquially, though the adjective has normally been avoided when referring to the European orchestral horn, ever since the German horn began replacing the French-style instrument in British orchestras around 1930.[6] The International Horn Society has recommended since 1971 that the instrument be simply called the horn.[7][8]

There is also a more specific use of "French horn" to describe a particular horn type, differentiated from the German horn and Vienna horn. In this sense, "French horn" refers to a narrow-bore instrument (10.8–11.0 mm [0.43–0.43 in]) with three Périnet (piston) valves. It retains the narrow bell-throat and mouthpipe crooks of the orchestral hand horn of the late 18th century, and most often has an "ascending" third valve. This is a whole-tone valve arranged so that with the valve in the "up" position the valve loop is engaged, but when the valve is pressed the loop is cut out, raising the pitch by a whole tone.[9]

History

[edit]

As the name indicates, humans originally used to blow on the actual horns of animals before starting to emulate naturally occurring horns with metal ones. The use of animal horns survives with the shofar, a ram's horn, which plays an important role in Jewish religious rituals.

Early metal horns were less complex than modern horns, consisting of valveless brass tubes, wound around a few times, with a slightly flared opening (the bell). These early "hunting" horns (French: cors de chasse) were originally played on a hunt, often while mounted, and the sound they produced was called a recheat. Change of pitch on these hunting horns was controlled entirely by the lips, as the use of valves and insertion of a hand in the bell to change pitch were later innovations. Without valves, only the notes within the harmonic series are available. By combining a long length with a narrow bore, the French horn's design allows the player to easily reach the higher overtones which differ by whole tones or less, thus making it capable of playing melodies before valves were invented.[4]

Early horns were commonly pitched in B♭ alto, A, A♭, G, F, E, E♭, D, C, and B♭ basso. Since the only notes available were those on the harmonic series of one of those pitches, horn-players had no ability to play in different keys. The remedy for this limitation was the use of crooks, i.e., sections of tubing of differing length that, when inserted, altered the length of the instrument, and thus its pitch.[10]

In the mid-18th century, horn players began to insert the right hand into the bell to change the length of the instrument, adjusting the tuning up to the distance between two adjacent harmonics depending on how much of the opening was covered.

In 1818 the German makers Heinrich Stölzel and Friedrich Blümel patented the first valved horn, using rotary valves. François Périnet introduced piston valves in France about 1839.[11] The use of valves initially aimed to overcome problems associated with changing crooks during a performance. Valves' unreliability, musical taste, and players' distrust, among other reasons, slowed their adoption into the mainstream. Many traditional conservatories and players refused to use them at first, claiming that the valveless horn, or natural horn, was a better instrument. Some musicians who specialize in period instruments use a natural horn to play in original performance styles, to try to recapture the sound of an older piece's original performances.[12]

There were many different versions of early valves, most being variants of the piston and rotary systems used in modern horns. Early valves by Blühmel are cited as possibly the first rotary valve, but the first confirmed rotary valve design was in 1832 by Joseph Riedl in Vienna. [clarification needed][13]

Types

[edit]Horns may be classified into single horn, double horn, compensating double horn, and triple horn as well as having the option of detachable bells.

Single horn

[edit]Single horns use a single set of tubes connected to the valves. This allows for simplicity of use and a much lighter weight. They are usually in the keys of F or B♭, although many F horns have longer slides to tune them to E♭, and almost all B♭ horns have a valve to put them in the key of A. The problem with single horns is the inevitable choice between accuracy or tone – while the F horn has the "typical" horn sound, above third-space C accuracy is a concern for the majority of players because, by its nature, one plays high in the horn's harmonic series where the overtones are closer together. This led to the development of the B♭ horn, which, although easier to play accurately, has a less desirable sound in the mid and especially the low register where it is not able to play all of the notes. The solution has been the development of the double horn, which combines the two into one horn with a single lead pipe and bell. Both main types of single horns are still used today as student models because they are cheaper and lighter than double horns. In addition, the single B♭ horns are sometimes used in solo and chamber performances and the single F survives orchestrally as the Vienna horn. Additionally, single F alto and B♭ alto descants are used in the performance of some baroque horn concertos and F, B♭ and F alto singles are occasionally used by jazz performers.

Dennis Brain's benchmark recordings of the Mozart Horn Concerti were made on a single B♭ instrument by Gebr. Alexander, now on display at the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Double horn

[edit]

- Mouthpiece

- Leadpipe, where the mouthpiece is placed

- Adjustable handrest

- Water key (also called a spit valve)

- Fourth valve to change between F and B♭ pitches

- Valve levers, operated with the left hand

- Rotary valves

- Slides, for tuning each valve

- Long tubing for F pitch with slide

- General slide

- Short tubing for B♭ pitch with slide

- Bellpipe

- Bell; the right hand is cupped inside this

Despite the introduction of valves, the single F horn proved difficult for use in the highest range, where the partials grew closer and closer, making accuracy a great challenge. An early solution was simply to use a horn of higher pitch—usually B♭. The use of the F versus the B♭ horn was extensively debated among horn players of the late 19th century, until the German horn maker Eduard Kruspe (namesake of his family's brass instrument firm) produced a prototype of the "double horn" in 1897.

The double horn also combines two instruments into a single frame: the original horn in F, and a second, higher horn keyed in B♭. By using a fourth valve (usually operated by the thumb), the horn player can quickly switch from the deep, warm tones of the F horn to the higher, brighter tones of the B♭ horn, or vice versa, as the horn player may choose to have the horn set into B♭ by default by making a simple adjustment to the valves. The two sets of tones are commonly called "sides" of the horn. Using the fourth valve not only changes the basic length (and thus the harmonic series and pitch) of the instrument, it also causes the three main valves to use proportionate slide lengths.[14]

Compensating double horn

[edit]A full double horn has two full-length sets of slides (one set for the B♭ side and a longer set for the F side); a compensating double horn only has full-length slides for the B♭ side and a shorter set of slides whose length can be added to the B♭ slides to give the necessary tubing length for playing in F. As for the full double horn, the air is routed through the appropriate slide(s) by use of the fourth valve. Compensating double horns are lighter than full double horns because of this design.[15]

Triple horn

[edit]A triple horn has more tubing, adding a descant horn to the double horn and hence giving more assistance for the high range. The descant horn is most commonly in F, sounding an octave higher than the normal F horn.[16]

Detachable bell

[edit]The horn, although not large, is awkward in its shape and does not lend itself well to transport where space is shared or limited, especially on planes. To compensate, horn makers can make the bell detachable; this allows for smaller and more manageable horn cases.

Related horns

[edit]The variety in horn history necessitates consideration of the natural horn, Vienna horn, mellophone, marching horn, and Wagner tuba.

Natural horn

[edit]

The natural horn is the ancestor of the modern horn. It is essentially descended from hunting horns, with its pitch controlled by air speed, aperture (opening of the lips through which air passes) and the use of the right hand moving around, as well as in and out of the bell. Although a few recent composers have written specifically for the natural horn (e.g., György Ligeti's Hamburg Concerto and sections of Paul Dukas' Villanelle for Horn and Piano), today it is played primarily as a period instrument. The natural horn can only play from a single harmonic series at a time because there is only one length of tubing available to the horn player. A proficient player can indeed alter the pitch by partially or fully muting the bell with the right hand, thus enabling the player to reach some notes that are not part of the instrument's natural harmonic series – of course this technique also affects the quality of the tone. The player has a choice of key by using crooks to change the length of tubing.[17][verification needed]

Vienna horn

[edit]

The Vienna horn is a special horn used primarily in Vienna, Austria. Instead of using rotary valves or piston valves, it uses the pumpenvalve (or Vienna valve), which is a double-piston operating inside the valve slides, and usually situated on the opposite side of the corpus from the player's left hand, and operated by a long pushrod. Unlike the modern horn, which has grown considerably larger internally (for a bigger, broader, and louder tone) and considerably heavier (with the addition of valves and tubing in the case of the double horn), the Vienna horn very closely mimics the size and weight of the natural horn (although the valves do add some weight, they are lighter than rotary valves), even using crooks in the front of the horn between the mouthpiece and the instrument. Instead of the full range of keys, Vienna horn players usually use an F crook; it is looked down upon to use others, though switching to an A or B♭ crook for higher pitched music does happen on occasion. Vienna horns are often used with funnel shaped mouthpieces similar to those used on the natural horn, with very little (if any) backbore and a very thin rim. The Viennese horn requires very specialized technique and can be quite challenging to play, even for accomplished players of modern horns. The Vienna horn has a warmer, softer sound than the modern horn. Its pumpenvalves facilitate a continuous transition between notes (glissando); conversely, a more precise operating of the valves is required to avoid notes that sound out of tune.

Mellophone

[edit]Two instruments are called a mellophone. The first is an instrument shaped somewhat like a horn, in that it is formed in a circle and is often referred to as a "classic" or "concert" mellophone. It has piston valves and is played with the right hand on the valves. Most are pitched in the key of F, with facility to switch to E♭either by changing crooks/leadpipes, or by a valve dedicated to this purpose. Older examples often included the ability to be played in the keys of D and/or C as well. Manufacturing of this instrument sharply decreased in the middle of the 20th century, and this mellophone (or mellophonium) rarely appears today.

The second instrument is used in modern brass bands and marching bands, and is more accurately called a "marching mellophone". A derivative of the F alto horn, it is keyed in F. It is shaped like a flugelhorn, with piston valves played with the right hand and a forward-pointing bell. These horns are generally considered better marching instruments than regular horns because their position is more stable on the mouth, they project better, and they weigh less. It is primarily used as the middle voice of drum and bugle corps. Though they are usually played with a V-cup cornet-like mouthpiece, their range overlaps the common playing range of the horn. This mouthpiece switch makes the mellophone louder, less mellow, and more brassy and brilliant, making it more appropriate for marching bands. Often now with the use of converters, traditional conical horn mouthpieces are used to achieve the more mellow sound of a horn to make the marching band sound more like a concert band.

As they are pitched in F or G and their range overlaps that of the horn, mellophones can be used in place of the horn in brass and marching band settings. Mellophones are, however, sometimes unpopular with horn players because the mouthpiece change can be difficult and requires a different embouchure. Mouthpiece adapters are available so that a horn mouthpiece can fit into the mellophone lead pipe (some of them are designed to where the end is bent at a 45-degree angle so that they can use the same embouchure), but this does not compensate for the many differences that a horn player must adapt to. The "feel" of the mellophone can be foreign to a horn player. Another unfamiliar aspect of the mellophone is that it is designed to be played with the right hand instead of the left (though it can be played with the left). Intonation can also be an issue with the mellophone.[why?]

While horn players may be asked to play the mellophone, it is unlikely that the instrument was ever intended as a substitute for the horn, mainly because of the fundamental differences described.[18] As an instrument it compromises between the ability to sound like a horn, while being used like a trumpet or flugelhorn, a tradeoff that sacrifices acoustic properties for ergonomics.

Marching horn

[edit]The marching horn is quite similar to the mellophone in shape and appearance, but it is pitched in the key of B♭, the same as the B♭ side of a double horn or valve trombone (which is also the same as a bass trumpet, an octave below a normal trumpet). It is also available in F alto, one octave above the F side of a double horn (or the high F side of a triple horn). The marching horn is also played with a horn mouthpiece (unlike the mellophone, which needs an adapter to fit the horn mouthpiece). These instruments are primarily used in marching bands so that the sound comes from a forward-facing bell, as dissipation of the sound from the backward-facing bell becomes a concern in open-air environments. Many college marching bands and drum corps, however, use mellophones instead, which, with many marching bands, better balance the tone of the other brass instruments; additionally, mellophones require less special training of trumpeters, who considerably outnumber horn players.[19] Some college marching bands use marching French horns when accompanying choirs as to not overpower their singing.

Wagner tuba

[edit]The Wagner tuba is a rare brass instrument that is essentially a horn modified to have a larger bell throat and a vertical bell. Despite its name and its somewhat tuba-shaped appearance, it is generally not considered part of the tuba family, because the instrument's relatively narrow bore causes it to play more like a horn. Invented for Richard Wagner specifically for his work Der Ring des Nibelungen, it has since been written for by various other composers, including Bruckner, Stravinsky and Richard Strauss. It uses a horn mouthpiece and is available as a single tuba in B♭ or F, or, more recently, as a double tuba similar to the double horn. It is usually played in a range similar to that of the euphonium, but its possible range is the same as that of the horn, extending from low F♯, below the bass clef staff to high C above the treble staff when read in F. The low pedal tones are substantially easier to play on the Wagner tuba than on the horn. Wagner viewed the regular horn as a woodwind rather than a brass instrument, evidenced by his placing of the horn parts in his orchestral scores in the woodwind group and not in their usual place above the trumpets in the brass section.

Repertoire

[edit]

Discussion of the repertoire of horns must recognize the different needs of orchestras and concert bands in contrast to marching bands, as above, but also the use of horns in a wide variety of music, including chamber music and jazz.

Orchestra and concert band

[edit]The horn is most often used as an orchestral and concert band instrument, with its singular tone being employed by composers to achieve specific effects. Leopold Mozart, for example, used horns to signify the hunt, as in his Jagdsinfonie (hunting symphony). Telemann wrote much for the horn, and it features prominently in the work of Handel and in Bach's Brandenburg Concerto no. 1. Once the technique of hand-stopping had been developed, allowing fully chromatic playing, composers began to write seriously for the horn. Gustav Mahler made great use of the horn's uniquely haunting and distant sound in his symphonies, notably the famous Nachtmusik (serenade) section of his Symphony No. 7.

Many composers have written works that have become favorites in the horn repertoire. These include Poulenc (Elegie) and Saint-Saëns (Morceau de Concert for horn and orchestra, op. 94 and Romance, op. 36). Others, particularly Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose friend Joseph Leutgeb was a noted horn player, wrote extensively for the instrument, including concerti and other solo works. Mozart's A Musical Joke satirizes the limitations of contemporary horn playing, including the risk of selecting the wrong crook by mistake.

The development of the valve horn was exploited by romantic composers such as Bruckner, Mahler, and Richard Strauss, whose father was a well-known professional horn player. Strauss's Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks contains one of the best known horn solos from this period, relying on the chromatic facility of the valved horn. Schumann's Konzertstück for four horns and orchestra is a notable three-movement work. Brahms had a lifelong love-affair with the instrument, with many prominently featured parts throughout his four symphonies. Despite his use of natural horns in his work (e.g., Horns in B♮ in the second movement of his Symphony No. 2), players today typically play Brahms's music on modern valved instruments.

Chamber music

[edit]There is an abundance of chamber music repertoire for horn. It is a standard member of the wind quintet and brass quintet, and often appears in other configurations, such as Brahms' Horn Trio for violin, horn and piano (for which, however, Brahms specified the natural horn). Also, the horn can be used by itself in a horn ensemble or "horn choir". The horn choir is especially practical because the extended range of the horn provides the composer or arranger with more possibilities, registerally, sonically, and contrapuntally.

Orchestral and concert band horns

[edit]

A classical orchestra usually has at least two French horn players. Typically, the first horn played a high part and the second horn played a low part. Composers from Beethoven (early 1800s) onwards commonly used four horns. Here, the first and second horns played as a pair (first horn being high, second horn being low), and the third and fourth horns played as another pair (third horn being high, fourth horn being low).

Music written for the modern horn follows a similar pattern with the first and third horns being high and the second and fourth horns being low. This configuration serves multiple purposes. It is easier to play high when the adjacent player is playing low and vice versa. Pairing makes it easier to write for horns, as the third and fourth horns can take over from the first and second horns or play contrasting material. For example, if the piece is in C minor, the first and second horns might be in C, the tonic major key, which could get most of the notes, and the third and fourth horns might be in E♭, the relative major key, to fill in the gaps.

Many orchestral horn sections in the 2010s also have an assistant[20] who doubles the first horn part for selected passages, joining in loud parts, playing instead of the principal if there is a first horn solo approaching, or alternating with the principal if the part is tiring to play.[21] Often the assistant is asked to play a passage after resting a long time. Also, he or she may be asked to enter in the middle of a passage, exactly matching the sound, articulation, and overall interpretation of the principal, thus enabling the principal horn to rest a bit.

In jazz

[edit]The French horn was at first rarely used in jazz music. (Note that colloquially in jazz, the word "horn" refers to any wind instrument.) Notable exponents, however, began including French horn in jazz pieces and ensembles. These include composer/arranger Gil Evans who included the French horn as an ensemble instrument from the 1940s, first in Claude Thornhill's groups, and later with the pioneering cool jazz nonet (nine-piece group) led by trumpeter Miles Davis, and in many other projects that sometimes also featured Davis, as well as Don Ellis, a trumpet player from Stan Kenton's jazz band. Notable works of Ellis' jazz French horn include "Strawberry Soup" and other songs on the album Tears of Joy. Notable improvising horn players in jazz include Julius Watkins, Willie Ruff, John Graas, David Amram, John Clark, Vincent Chancey, Giovanni Hoffer, Arkady Shilkloper, Adam Unsworth, and Tom Varner.

Bass clef old notation vs. new notation

[edit]Notation in the bass clef for the horn has undergone a convention shift. Prior to approximately 1920, horn parts employing the bass clef often used what is now referred to as old notation. In this system, notes in the bass clef were written in octaves below concert pitch rather than above. By the early 20th century, as the valve horn became standard, the new notation gradually replaced the old system.[22] In new notation, transposition in the bass clef follows the same rule as the treble clef, that is, to write notes in the octave above concert pitch.

Usually there is no indication on the score for whether the horn parts are written in old or new notation. However, horn players have developed a general rule-of-thumb to determine which notation is being used.[23]

Notable horn players

[edit]- Hermann Baumann – 1964 winner of the ARD International Music Competition and former principal horn in various orchestras, including the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra

- Radek Baborák – famous Czech horn player, former principal horn in Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, 1994 winner of the ARD International Music Competition, winner of the Concertino Praga in 1988 and 1990, holder of a Grammy Award (1995)

- Aubrey Brain – celebrated British horn player, father of Dennis Brain and a champion of the French style of instrument

- Dennis Brain – former principal horn of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Philharmonia Orchestra, with whom Herbert von Karajan made well-known recordings of Mozart's horn concertos

- Alan Civil – former principal horn of the Philharmonia Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and the BBC Symphony Orchestra

- John Cerminaro – former principal horn of the Seattle Symphony, New York Philharmonic, and Los Angeles Philharmonic

- Dale Clevenger – former principal horn of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1966–2013)

- Vincent DeRosa – former principal horn for a number of Hollywood studios and composers including John Williams

- Stefan Dohr – current principal horn, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Richard Dunbar – a player of the French horn, playing in the free jazz scene

- Philip Farkas – former principal horn of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, developer of the Holton-Farkas horn and author of several books on horn and brass playing

- Douglas Hill – former principal horn of the Madison Symphony Orchestra, notable teacher and composer

- Julie Landsman – former Principal Horn for the Metropolitan Opera and well-known horn pedagogue

- Stefan de Leval Jezierski – longest serving horn, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Philip Myers – former principal horn of the New York Philharmonic

- Jeff Nelsen – Canadian Brass hornist 2000–2004, 2007–2010; Indiana University Jacobs School of Music horn faculty since 2006

- Giovanni Punto – horn virtuoso and hand-stopping pioneer, after whom the International Horn Society's annual horn playing award is named, also a violinist, concertmaster, and composer

- David Pyatt – winner of the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition in 1988 and current principal horn of the London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Gunther Schuller – former principal horn of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and played with Miles Davis

- Lucien Thévet - Principal horn of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, of the Orchestre de l'Opéra National de Paris, notable teacher and author of several books on horn playing

- Barry Tuckwell – former principal horn of the London Symphony Orchestra and author of several books on horn playing

- Radovan Vlatković – 1983 winner of the ARD International Music Competition, former principal horn and soloist of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and professor at the Mozarteum University of Salzburg

- Sarah Willis – first female brass-player in the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, US-born, British ambassador for the horn and classical music through television programs such as Sarah's Music on Deutsche Welle.

People who are more notable for their other achievements, but also play the horn, include actors Ewan McGregor and David Ogden Stiers, comedian and television host Jon Stewart, journalist Chuck Todd, The Who bassist and singer John Entwistle, and rapper and record producer B.o.B.[24]

Gallery

[edit]-

A modern full double horn

-

A hunting horn

-

A French Omnitonic horn

-

A natural horn at the Victoria and Albert Museum

-

A replica of a Mozart-era natural horn

-

A hunting horn in E♭

-

A natural horn

-

An older, French-made cor à pistons in E♭

-

A French-made horn with piston valves

-

A horn by Alexander, once owned by Dennis Brain

-

A French horn in Berlin

-

A rose gold French Horn

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Piston, Walter (1955). Orchestration (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0393097405. OCLC 300471.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Whitener, Scott and Cathy L. (1990). A complete guide to brass : instruments and pedagogy. New York: Schirmer Books. pp. 40, 44. ISBN 978-0028728612. OCLC 19128016.

- ^ Pope, Ken. "Alexander 107 Descant w/Stopping Valve - $7800". Pope Instrument Repair. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ a b c d Farkas, Philip (1956). The art of French horn playing : a treatise on the problems and techniques of French Horn playing ... Evanston, Il.: Summy-Birchard. pp. 6, 21, 65. ISBN 978-0874870213. OCLC 5587694.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Beakes, Jennifer (2007). The Horn Parts in Handel's Operas and Oratorios and the Horn Players who Performed in These Works. City University of New York. pp. 50, 116–18, 176, 223–25, 439–40, 444–45.

- ^ Del Mar, Norman (1983). Anatomy of the orchestra (2nd print., with revisions ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0520045002. OCLC 10561390.

- ^ Meek, Harold. "Harold Meek (1914–1998)". International Horn Society. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

Harold Meek is described by everyone as a gentleman, a perfectionist, and one who loved the horn. He was the first editor of The Horn Call and was responsible for this statement in every issue, 'The International Horn Society recommends that HORN be recognized as the correct name for our instrument in the English language.'

- ^ Meek, Harold (February 1971). "The Horn!". The Horn Call. 1 (1): 19–20.

Meek strongly advocates using the term 'horn' rather than 'French horn.'

- ^ Baines, Anthony (1976). Brass instruments : their history and development. New York: Scribner. pp. 221–23. ISBN 978-0684152295. OCLC 3795926.

- ^ "Grinell College Musical". Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- ^ Meek, Harold L. (1997). Horn and conductor : reminiscences of a practitioner with a few words of advice. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1878822833. OCLC 35636932.

- ^ See, e.g., the performance of Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor as performed by the Proms of London in the movement from 45:40 onward in "Mass in B Minor". YouTube. 2012. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ Tuckwell, Barry (1983). Horn. New York: Schirmer Books. pp. 41–46. ISBN 0-02-871530-6.

- ^ Backus, John, The Acoustical Foundations of Music, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1977),[page needed] ISBN 0-393-09096-5.

- ^ Ericson, John (17 December 2008). "What is a Compensating Double?".

- ^ Ericson, John. "Playing Descant and Triple Horns".

- ^ Diagram Group. (1976). Musical instruments of the world. Published for Unicef by Facts On File. p. 68. ISBN 0871963205. OCLC 223164947.

- ^ Monks, Greg (2006-01-06). "The History of the Mellophone". Al's Mellophone Page. Archived from the original on 2022-08-21. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ Mellophones, as indicated, use the same fingering as trumpets and are operated by the right hand.

- ^ Ericson, John (28 March 2010). "Horn Sections with and Without an associate principal". Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Bacon, Thomas. "The Horn Section". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Ericson, John (27 April 2025). "Fundamentals 18A. Bass clef: old (and new) notation bass clef". Horn Matters. Retrieved 7 October 2025.

- ^ Hembd, Bruce (26 August 2008). "Transposition Tricks: Old vs. New Notation". Horn Matters. Retrieved 7 October 2025.

- ^ Rees, Jasper (2009). A Devil to Play. HarperCollins.

External links

[edit]- Homepage of the International Horn Society, one of the largest organizations of horn players in the world.

- British Horn Society, UK-based organisation for horn playing

- First steps of making a horn by hand (QuickTime Movie) at Finke Horns

- From mines to music: The venerable valve, by musicologist Edmund A. Bowles

- Horn maintenance Archived 2017-06-30 at the Wayback Machine at Paxman, compiled with the assistance of Simon de Souza

- How to dismantle a valve at Finke Horns

- Horn Etudes - List of horn etudes