Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dynein

View on Wikipedia

Dyneins are a family of cytoskeletal motor proteins (though they are actually protein complexes) that move along microtubules in cells. They convert the chemical energy stored in ATP to mechanical work. Dynein transports various cellular cargos, provides forces and displacements important in mitosis, and drives the beat of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. All of these functions rely on dynein's ability to move towards the minus-end of the microtubules, known as retrograde transport; thus, they are called "minus-end directed motors". In contrast, most kinesin motor proteins move toward the microtubules' plus-end, in what is called anterograde transport.

Classification

[edit]| Dynein heavy chain, N-terminal region 1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | DHC_N1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08385 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013594 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynein heavy chain, N-terminal region 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | DHC_N2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08393 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013602 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynein heavy chain and region D6 of dynein motor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Dynein_heavy | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03028 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR004273 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynein light intermediate chain (DLIC) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||

| Symbol | DLIC | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF05783 | ||||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0023 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Dynein light chain type 1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

structure of the human pin/lc8 dimer with a bound peptide | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Dynein_light | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01221 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001372 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00953 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1bkq / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Roadblock | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Structure of Roadblock/LC7 protein - RCSB PDB 1y4o | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Robl1, Robl2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03259 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR016561 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1y4o / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Dyneins can be divided into two groups: cytoplasmic dyneins and axonemal dyneins, which are also called ciliary or flagellar dyneins.

- cytoplasmic

- axonemal

Function

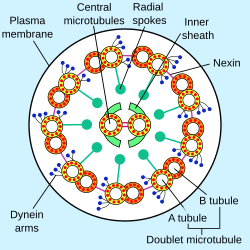

[edit]Axonemal dynein causes sliding of microtubules in the axonemes of cilia and flagella and is found only in cells that have those structures.

Cytoplasmic dynein, found in all animal cells and possibly plant cells as well, performs functions necessary for cell survival such as organelle transport and centrosome assembly.[1] Cytoplasmic dynein moves processively along the microtubule; that is, one or the other of its stalks is always attached to the microtubule so that the dynein can "walk" a considerable distance along a microtubule without detaching.

Cytoplasmic dynein helps to position the Golgi complex and other organelles in the cell.[1] It also helps transport cargo needed for cell function such as vesicles made by the endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, and lysosomes (Karp, 2005). Dynein is involved in the movement of chromosomes and positioning the mitotic spindles for cell division.[2][3] Dynein carries organelles, vesicles and possibly microtubule fragments along the axons of neurons toward the cell body in a process called retrograde axonal transport.[1] Additionally, dynein motor is also responsible for the transport of degradative endosomes retrogradely in the dendrites.[4]

Mitotic spindle positioning

[edit]Cytoplasmic dynein positions the spindle at the site of cytokinesis by anchoring to the cell cortex and pulling on astral microtubules emanating from centrosome. While a postdoctoral student at MIT, Tomomi Kiyomitsu discovered how dynein has a role as a motor protein in aligning the chromosomes in the middle of the cell during the metaphase of mitosis. Dynein pulls the microtubules and chromosomes to one end of the cell. When the end of the microtubules become close to the cell membrane, they release a chemical signal that punts the dynein to the other side of the cell. It does this repeatedly so the chromosomes end up in the center of the cell, which is necessary in mitosis.[5][6][7][8] Budding yeast have been a powerful model organism to study this process and has shown that dynein is targeted to plus ends of astral microtubules and delivered to the cell cortex via an offloading mechanism.[9][10]

Viral replication

[edit]Dynein and kinesin can both be exploited by viruses to mediate the viral replication process. Many viruses use the microtubule transport system to transport nucleic acid/protein cores to intracellular replication sites after invasion host the cell membrane.[11] Not much is known about virus' motor-specific binding sites, but it is known that some viruses contain proline-rich sequences (that diverge between viruses) which, when removed, reduces dynactin binding, axon transport (in culture), and neuroinvasion in vivo.[12] This suggests that proline-rich sequences may be a major binding site that co-opts dynein.

Structure

[edit]

Each molecule of the dynein motor is a complex protein assembly composed of many smaller polypeptide subunits. Cytoplasmic and axonemal dynein contain some of the same components, but they also contain some unique subunits.

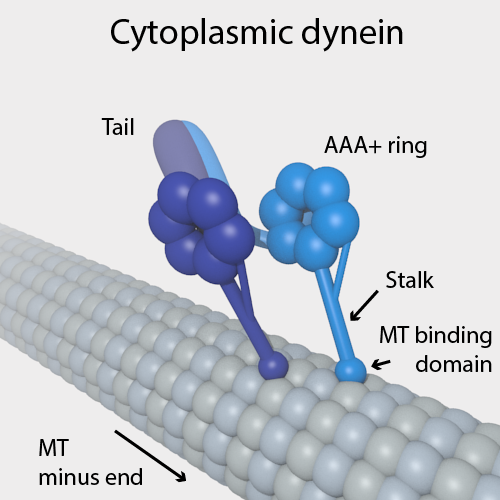

Cytoplasmic dynein

[edit]Cytoplasmic dynein, which has a molecular mass of about 1.5 megadaltons (MDa), is a dimer of dimers, containing approximately twelve polypeptide subunits: two identical "heavy chains", 520 kDa in mass, which contain the ATPase activity and are thus responsible for generating movement along the microtubule; two 74 kDa intermediate chains which are believed to anchor the dynein to its cargo; two 53–59 kDa light intermediate chains; and several light chains.

The force-generating ATPase activity of each dynein heavy chain is located in its large doughnut-shaped "head", which is related to other AAA proteins, while two projections from the head connect it to other cytoplasmic structures. One projection, the coiled-coil stalk, binds to and "walks" along the surface of the microtubule via a repeated cycle of detachment and reattachment. The other projection, the extended tail, binds to the light intermediate, intermediate and light chain subunits which attach dynein to its cargo. The alternating activity of the paired heavy chains in the complete cytoplasmic dynein motor enables a single dynein molecule to transport its cargo by "walking" a considerable distance along a microtubule without becoming completely detached.

In the apo-state of dynein, the motor is nucleotide free, the AAA domain ring exists in an open conformation,[14] and the MTBD exists in a high affinity state.[15] Much about the AAA domains remains unknown,[16] but AAA1 is well established as the primary site of ATP hydrolysis in dynein.[17] When ATP binds to AAA1, it initiates a conformational change of the AAA domain ring into the "closed" configuration, movement of the buttress,[14] and a conformational change in the linker.[18][19] The linker becomes bent and shifts from AAA5 to AAA2 while remaining bound to AAA1.[14][19] One attached alpha-helix from the stalk is pulled by the buttress, sliding the helix half a heptad repeat relative to its coilled-coil partner,[15][20] and kinking the stalk.[14] As a result, the MTBD of dynein enters a low-affinity state, allowing the motor to move to new binding sites.[21][22] Following hydrolysis of ATP, the stalk rotates, moving dynein further along the MT.[18] Upon the release of the phosphate, the MTBD returns to a high affinity state and rebinds the MT, triggering the power stroke.[23] The linker returns to a straight conformation and swings back to AAA5 from AAA2[24][25] and creates a lever-action,[26] producing the greatest displacement of dynein achieved by the power stroke[18] The cycle concludes with the release of ADP, which returns the AAA domain ring back to the "open" configuration.[22]

Yeast dynein can walk along microtubules without detaching, however in metazoans, cytoplasmic dynein must be activated by the binding of dynactin, another multisubunit protein that is essential for mitosis, and a cargo adaptor.[27] The tri-complex, which includes dynein, dynactin and a cargo adaptor, is ultra-processive and can walk long distances without detaching in order to reach the cargo's intracellular destination. Cargo adaptors identified thus far include BicD2, Hook3, FIP3 and Spindly.[27] The light intermediate chain, which is a member of the Ras superfamily, mediates the attachment of several cargo adaptors to the dynein motor.[28] The other tail subunits may also help facilitate this interaction as evidenced in a low resolution structure of dynein-dynactin-BicD2.[29]

One major form of motor regulation within cells for dynein is dynactin. It may be required for almost all cytoplasmic dynein functions.[30] Currently, it is the best studied dynein partner. Dynactin is a protein that aids in intracellular transport throughout the cell by linking to cytoplasmic dynein. Dynactin can function as a scaffold for other proteins to bind to. It also functions as a recruiting factor that localizes dynein to where it should be.[31][32] There is also some evidence suggesting that it may regulate kinesin-2.[33] The dynactin complex is composed of more than 20 subunits,[29] of which p150(Glued) is the largest.[34] There is no definitive evidence that dynactin by itself affects the velocity of the motor. It does, however, affect the processivity of the motor.[35] The binding regulation is likely allosteric: experiments have shown that the enhancements provided in the processivity of the dynein motor do not depend on the p150 subunit binding domain to the microtubules.[36]

Axonemal dynein

[edit]

Axonemal dyneins come in multiple forms that contain either one, two or three non-identical heavy chains (depending upon the organism and location in the cilium). Each heavy chain has a globular motor domain with a doughnut-shaped structure believed to resemble that of other AAA proteins, a coiled coil "stalk" that binds to the microtubule, and an extended tail (or "stem") that attaches to a neighboring microtubule of the same axoneme. Each dynein molecule thus forms a cross-bridge between two adjacent microtubules of the ciliary axoneme. During the "power stroke", which causes movement, the AAA ATPase motor domain undergoes a conformational change that causes the microtubule-binding stalk to pivot relative to the cargo-binding tail with the result that one microtubule slides relative to the other (Karp, 2005). This sliding produces the bending movement needed for cilia to beat and propel the cell or other particles. Groups of dynein molecules responsible for movement in opposite directions are probably activated and inactivated in a coordinated fashion so that the cilia or flagella can move back and forth. The radial spoke has been proposed as the (or one of the) structures that synchronizes this movement.

The regulation of axonemal dynein activity is critical for flagellar beat frequency and cilia waveform. Modes of axonemal dynein regulation include phosphorylation, redox, and calcium. Mechanical forces on the axoneme also affect axonemal dynein function. The heavy chains of inner and outer arms of axonemal dynein are phosphorylated/dephosphorylated to control the rate of microtubule sliding. Thioredoxins associated with the other axonemal dynein arms are oxidized/reduced to regulate where dynein binds in the axoneme. Centerin and components of the outer axonemal dynein arms detect fluctuations in calcium concentration. Calcium fluctuations play an important role in altering cilia waveform and flagellar beat frequency (King, 2012).[37]

History

[edit]The protein responsible for movement of cilia and flagella was first discovered and named dynein in 1963 (Karp, 2005). 20 years later, cytoplasmic dynein, which had been suspected to exist since the discovery of flagellar dynein, was isolated and identified (Karp, 2005).

Chromosome segregation during meiosis

[edit]Segregation of homologous chromosomes to opposite poles of the cell occurs during the first division of meiosis. Proper segregation is essential for producing haploid meiotic products with a normal complement of chromosomes. The formation of chiasmata (crossover recombination events) appears to generally facilitate proper segregation. However, in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, when chiasmata are absent, dynein promotes segregation.[38] Dhc1, the motor subunit of dynein, is required for chromosomal segregation in both the presence and absence of chiasmata.[38] The dynein light chain Dlc1 protein is also required for segregation, specifically when chiasmata are absent.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Karp G, Beginnen K, Vogel S, Kuhlmann-Krieg S (2005). Molekulare Zellbiologie (in French). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-23857-7.

- ^ Samora CP, Mogessie B, Conway L, Ross JL, Straube A, McAinsh AD (August 2011). "MAP4 and CLASP1 operate as a safety mechanism to maintain a stable spindle position in mitosis". Nature Cell Biology. 13 (9): 1040–50. doi:10.1038/ncb2297. PMID 21822276. S2CID 8869880.

- ^ Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM (February 2012). "Chromosome- and spindle-pole-derived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation". Nature Cell Biology. 14 (3): 311–7. doi:10.1038/ncb2440. PMC 3290711. PMID 22327364.

- ^ Yap CC, Digilio L, McMahon LP, Wang T, Winckler B (April 2022). "Dynein is required for Rab7-dependent endosome maturation, retrograde dendritic transport, and degradation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 42 (22): 4415–4434. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2530-21.2022. PMC 9172292. PMID 35474277.

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325479623_Dynein-Dynactin-NuMA_clusters_generate_cortical_spindle-pulling_forces_as_a_multi-arm_ensemble doi:10.7554/eLife.36559

- ^ Eshel D, Urrestarazu LA, Vissers S, Jauniaux JC, van Vliet-Reedijk JC, Planta RJ, Gibbons IR (December 1993). "Cytoplasmic dynein is required for normal nuclear segregation in yeast". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (23): 11172–6. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9011172E. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.11172. PMC 47944. PMID 8248224.

- ^ Li YY, Yeh E, Hays T, Bloom K (November 1993). "Disruption of mitotic spindle orientation in a yeast dynein mutant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (21): 10096–100. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9010096L. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.21.10096. PMC 47720. PMID 8234262.

- ^ Carminati JL, Stearns T (August 1997). "Microtubules orient the mitotic spindle in yeast through dynein-dependent interactions with the cell cortex". The Journal of Cell Biology. 138 (3): 629–41. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.3.629. PMC 2141630. PMID 9245791.

- ^ Lee WL, Oberle JR, Cooper JA (February 2003). "The role of the lissencephaly protein Pac1 during nuclear migration in budding yeast". The Journal of Cell Biology. 160 (3): 355–64. doi:10.1083/jcb.200209022. PMC 2172672. PMID 12566428.

- ^ Lee WL, Kaiser MA, Cooper JA (January 2005). "The offloading model for dynein function: differential function of motor subunits". The Journal of Cell Biology. 168 (2): 201–7. doi:10.1083/jcb.200407036. PMC 2171595. PMID 15642746.

- ^ Valle-Tenney R, Opazo T, Cancino J, Goff SP, Arriagada G (August 2016). "Dynein Regulators Are Important for Ecotropic Murine Leukemia Virus Infection". Journal of Virology. 90 (15): 6896–6905. doi:10.1128/JVI.00863-16. PMC 4944281. PMID 27194765.

- ^ Zaichick SV, Bohannon KP, Hughes A, Sollars PJ, Pickard GE, Smith GA (February 2013). "The herpesvirus VP1/2 protein is an effector of dynein-mediated capsid transport and neuroinvasion". Cell Host & Microbe. 13 (2): 193–203. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.009. PMC 3808164. PMID 23414759.

- ^ PDB: 4RH7; Carter AP (February 2013). "Crystal clear insights into how the dynein motor moves". Journal of Cell Science. 126 (Pt 3): 705–13. doi:10.1242/jcs.120725. PMID 23525020.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt H, Zalyte R, Urnavicius L, Carter AP (February 2015). "Structure of human cytoplasmic dynein-2 primed for its power stroke". Nature. 518 (7539): 435–438. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..435S. doi:10.1038/nature14023. PMC 4336856. PMID 25470043.

- ^ a b Carter AP, Vale RD (February 2010). "Communication between the AAA+ ring and microtubule-binding domain of dynein". Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 88 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1139/o09-127. PMC 2894566. PMID 20130675.

- ^ Kardon JR, Vale RD (December 2009). "Regulators of the cytoplasmic dynein motor". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 10 (12): 854–65. doi:10.1038/nrm2804. PMC 3394690. PMID 19935668.

- ^ PDB: 1HN5; Mocz G, Gibbons IR (February 2001). "Model for the motor component of dynein heavy chain based on homology to the AAA family of oligomeric ATPases". Structure. 9 (2). London, England: 93–103. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00557-8. PMID 11250194.

- ^ a b c Roberts AJ, Numata N, Walker ML, Kato YS, Malkova B, Kon T, Ohkura R, Arisaka F, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, Burgess SA (February 2009). "AAA+ Ring and linker swing mechanism in the dynein motor". Cell. 136 (3): 485–95. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.049. PMC 2706395. PMID 19203583.

- ^ a b Roberts AJ, Malkova B, Walker ML, Sakakibara H, Numata N, Kon T, Ohkura R, Edwards TA, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, Oiwa K, Burgess SA (October 2012). "ATP-driven remodeling of the linker domain in the dynein motor". Structure. 20 (10): 1670–80. doi:10.1016/j.str.2012.07.003. PMC 3469822. PMID 22863569.

- ^ Kon T, Imamula K, Roberts AJ, Ohkura R, Knight PJ, Gibbons IR, Burgess SA, Sutoh K (March 2009). "Helix sliding in the stalk coiled coil of dynein couples ATPase and microtubule binding". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 16 (3): 325–33. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1555. PMC 2757048. PMID 19198589.

- ^ Carter AP (February 2013). "Crystal clear insights into how the dynein motor moves". Journal of Cell Science. 126 (Pt 3): 705–13. doi:10.1242/jcs.120725. PMID 23525020.

- ^ a b Bhabha G, Cheng HC, Zhang N, Moeller A, Liao M, Speir JA, Cheng Y, Vale RD (November 2014). "Allosteric communication in the dynein motor domain". Cell. 159 (4): 857–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.018. PMC 4269335. PMID 25417161.

- ^ Bhabha G, Johnson GT, Schroeder CM, Vale RD (January 2016). "How Dynein Moves Along Microtubules". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 41 (1): 94–105. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.004. PMC 4706479. PMID 26678005.

- ^ Gennerich A, Carter AP, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD (November 2007). "Force-induced bidirectional stepping of cytoplasmic dynein". Cell. 131 (5): 952–65. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.016. PMC 2851641. PMID 18045537.

- ^ Burgess SA, Knight PJ (April 2004). "Is the dynein motor a winch?". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 14 (2): 138–46. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.013. PMID 15093827.

- ^ Reck-Peterson SL, Yildiz A, Carter AP, Gennerich A, Zhang N, Vale RD (July 2006). "Single-molecule analysis of dynein processivity and stepping behavior". Cell. 126 (2): 335–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.046. PMC 2851639. PMID 16873064.

- ^ a b McKenney RJ, Huynh W, Tanenbaum ME, Bhabha G, Vale RD (July 2014). "Activation of cytoplasmic dynein motility by dynactin-cargo adapter complexes". Science. 345 (6194): 337–41. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..337M. doi:10.1126/science.1254198. PMC 4224444. PMID 25035494.

- ^ Schroeder CM, Ostrem JM, Hertz NT, Vale RD (October 2014). "A Ras-like domain in the light intermediate chain bridges the dynein motor to a cargo-binding region". eLife. 3 e03351. doi:10.7554/eLife.03351. PMC 4359372. PMID 25272277.

- ^ a b Urnavicius L, Zhang K, Diamant AG, Motz C, Schlager MA, Yu M, Patel NA, Robinson CV, Carter AP (March 2015). "The structure of the dynactin complex and its interaction with dynein". Science. 347 (6229): 1441–1446. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1441U. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4080. PMC 4413427. PMID 25814576.

- ^ Karki S, Holzbaur EL (February 1999). "Cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin in cell division and intracellular transport". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 11 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80006-4. PMID 10047518.

- ^ Moughamian AJ, Osborn GE, Lazarus JE, Maday S, Holzbaur EL (August 2013). "Ordered recruitment of dynactin to the microtubule plus-end is required for efficient initiation of retrograde axonal transport". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (32): 13190–203. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0935-13.2013. PMC 3735891. PMID 23926272.

- ^ Moughamian AJ, Holzbaur EL (April 2012). "Dynactin is required for transport initiation from the distal axon". Neuron. 74 (2): 331–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.025. PMC 3347924. PMID 22542186.

- ^ Berezuk MA, Schroer TA (February 2007). "Dynactin enhances the processivity of kinesin-2". Traffic. 8 (2): 124–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00517.x. PMID 17181772. S2CID 46446471.

- ^ Schroer TA (8 October 2004). "Dynactin". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 20 (1): 759–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.094623. PMID 15473859.

- ^ King SJ, Schroer TA (January 2000). "Dynactin increases the processivity of the cytoplasmic dynein motor". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (1): 20–4. doi:10.1038/71338. PMID 10620802. S2CID 20349195.

- ^ Kardon JR, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD (April 2009). "Regulation of the processivity and intracellular localization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae dynein by dynactin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (14): 5669–74. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5669K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900976106. PMC 2657088. PMID 19293377.

- ^ King SM (August 2012). "Integrated control of axonemal dynein AAA(+) motors". Journal of Structural Biology. 179 (2): 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2012.02.013. PMC 3378790. PMID 22406539.

- ^ a b Davis L, Smith GR (June 2005). "Dynein promotes achiasmate segregation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe". Genetics. 170 (2): 581–90. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.040253. PMC 1450395. PMID 15802518.

Further reading

[edit]- Karp G (2005). Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 346–358. ISBN 978-0-471-19279-4.

- Schroer TA (2004). "Dynactin". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 20 (1): 759–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.094623. PMID 15473859.

External links

[edit]- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_Dynein_DLC8_1

- Ron Vale's Seminar: "Molecular Motor Proteins"

- Dynein at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- EC 3.6.4.2